Adequate lifestyle changes significantly reduce the cardiovascular risk factors associated with prediabetes and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Therefore, healthy eating habits, regular physical activity, abstaining from using tobacco, and good sleep hygiene are recommended for managing these conditions. There is solid evidence that diets that are plant-based; low in saturated fatty acids, cholesterol, and sodium; and high in fiber, potassium, and unsaturated fatty acids are beneficial and reduce the expression of cardiovascular risk factors in these subjects. In view of the foregoing, the Mediterranean diet, the DASH diet, a low-carbohydrate diet, and a vegan-vegetarian diet are of note. Additionally, the relationship between nutrition and these metabolic pathologies is fundamental in targeting efforts to prevent weight gain, reducing excess weight in the case of individuals with overweight or obesity, and personalizing treatment to promote patient empowerment.

This document is the executive summary of an updated review that includes the main recommendations for improving dietary nutritional quality in people with prediabetes or type 2 diabetes mellitus. The full review is available on the webpages of the Spanish Society of Arteriosclerosis, the Spanish Diabetes Society, and the Spanish Society of Internal Medicine.

Los cambios adecuados del estilo de vida reducen significativamente los factores de riesgo cardiovascular asociados a la prediabetes y la diabetes mellitus tipo 2, por lo que en su manejo se debe recomendar un patrón saludable de alimentación, actividad física regular, no consumir tabaco, y una buena higiene del sueño. Hay una sólida evidencia de que los patrones alimentarios de base vegetal, bajos en ácidos grasos saturados, colesterol y sodio, con un alto contenido en fibra, potasio y ácidos grasos insaturados, son beneficiosos y reducen la expresión de los factores de riesgo cardiovascular en estos sujetos. En este contexto destacan la dieta mediterránea, la dieta DASH, la dieta baja en hidratos de carbono y la dieta vegano-vegetariana. Adicionalmente, en la relación entre nutrición y estas enfermedades metabólicas es fundamental dirigir los esfuerzos a prevenir la ganancia de peso o a reducir su exceso en caso de sobrepeso u obesidad, y personalizar el tratamiento para favorecer el empoderamiento del paciente.

Este documento es un resumen ejecutivo de una revisión actualizada que incluye las principales recomendaciones para mejorar la calidad nutricional de la alimentación en las personas con prediabetes o diabetes mellitus tipo 2, disponible en las páginas web de la Sociedad Española de Arteriosclerosis, la Sociedad Española de Diabetes y la Sociedad Española de Medicina Interna.

Prediabetes and type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM2) are diseases whose ever increasing incidence has become a serious public health problem. From a clinical point of view, control of these metabolic disorders has a direct impact on cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, making it important to develop effective prevention and treatment strategies.

Adequate lifestyle changes significantly reduce cardiovascular risk factors (CVRF) associated with prediabetes and DM2, so management should include recommendations on healthy eating, regular physical activity, not smoking and good sleep hygiene.1

There is solid evidence that plant-based diets, low in saturated fatty acids, cholesterol and sodium, and high in fibre, potassium and unsaturated fatty acids, are beneficial and reduce the expression of CVRF in these subjects.2 Such diets include the Mediterranean diet,3 a low-carbohydrate (CH) diet4 and a vegan-vegetarian diet.5

In view of the relationship between nutrition and these metabolic diseases, it is therefore essential that we focus our efforts on preventing weight gain, or reducing excess weight in the case of overweight or obese individuals, and personalising the treatment to promote patient empowerment.

With this document we present an updated review providing useful evidence and recommendations ranked by levels. The evidence is drawn from clinical trials, where available, observational studies on clinical evidence or surrogate markers, and expert consensus. Based on this, three types of recommendation will be made: (1) strong, based on clinical trials and meta-analyses that incorporate quality criteria; (2) moderate, supported by prospective cohort studies and case-control studies; and (3) weak, justified by consensus and expert opinion or based on extensive clinical practice.

In summary, evidence shows that a high proportion of adults have prediabetes or DM2, with the consequent increase in cardiovascular risk (CVR) in the short and medium term. Lifestyle, especially diet, forms the substantive basis of treatment to improve blood glucose, lipid and blood pressure control, and reduce the high cardiovascular morbidity and mortality rates in these people.1

This document is an executive summary of an updated review, which includes the main recommendations for improving the nutritional quality of diet in people with prediabetes or DM2, and which is available on the websites of the Spanish Arteriosclerosis Society (https://www.se-arteriosclerosis.org/guias-documentos-consenso), the Spanish Diabetes Association (https://www.sediabetes.org/grid/?tipo=cursos_formacion&categoria=consensos-guias-y-recomendaciones) and the Spanish Society of Internal Medicine (https://www.fesemi.org/actualizacion-en-el-tratamiento-de-la-prediabetes-y-la-diabetes-tipo-2-consenso-semi-sed-y-sea).

Dietary goals in the population with prediabetes or type 2 diabetesThe general aim of dietary treatment in people with prediabetes or DM2 is to help them change their eating habits to prevent and/or delay the disease, improve their metabolic control, treat complications and associated processes or comorbidities, and maintain or improve their quality of life. This general aim includes specific objectives applicable to the majority of the population with DM2 or at risk of developing it, which are supported by robust information.1,6–8

The specific dietary aims in the population with prediabetes or DM2 are:

- •

To prevent and/or delay progression to DM2 in people with prediabetes. Programmes that combine a healthy diet and physical activity are effective in reducing the incidence of DM2 and improving CVRF, and the more intensive the programme, the more effective it is8(Strong evidence).

- •

To achieve and maintain the personalised blood glucose control goals. Different nutritional interventions in people with DM2, including reducing calorie intake, lead to absolute decreases in glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c) of 0.3%–2.0% at three to six months, with these decreases maintained or even improved at 12 months and beyond. The improvement is greater in subjects who have been recently diagnosed and/or who have higher baseline HbA1c levels. It also then becomes possible to reduce the dose and/or number of antidiabetic drugs8(Strong evidence).

- •

To achieve and maintain personalised target weight. In adults with DM2, nutritional therapy facilitates weight loss (2.4–6.2 kg) or results in no change in weight8(Moderate evidence).

- •

To achieve and maintain personalised blood pressure and lipid control goals. Nutritional interventions in people with normal or close to normal values improve or do not change the lipid profile and blood pressure8(Moderate evidence).

- •

To maintain or improve quality of life. In people with DM2, the implementation of nutritional therapy significantly improves self-perception of state of health, increases knowledge and motivation, and reduces emotional stress8(Strong evidence).

A diet’s calorie intake is calculated to achieve and maintain a “reasonable” body weight; this being a weight which is more realistic than the ideal weight, is achievable and can be maintained in both the short and the long term.1

The majority (around 80%) of people with DM2 are obese, so weight reduction is initially the main therapeutic goal. Obesity, especially abdominal obesity, is the main factor contributing to the development of DM2 in genetically predisposed subjects, and obesity prevention is the main measure in reducing the incidence of DM2. There is solid evidence on the efficacy of moderate weight loss (5–10%) in preventing or delaying the progression of prediabetes to DM2.9,10

Along with a moderate reduction in calories (≥500 kcal/day), physical exercise, behaviour modification in terms of eating habits, and psychological support are the effective measures most commonly used to obtain and maintain gradual, moderate weight loss. However, the clinical benefits of weight loss are progressive and proportional to the amount of weight lost.11,12

An alternative for obese patients with DM2 who cannot lose weight within a structured programme, and in certain selected subjects, is the very low calorie diet (<800 kcal/day). This is generally liquid, maintained for short periods (<3 months) and with gradual reintroduction of food, which achieves marked weight loss plus remission of DM2 at one year in 50% of subjects.12

Healthy diet models for the treatment of diabetesThere are various dietary models or patterns considered healthy.13 The best known models are: the Mediterranean diet, the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet, the low CH diet and the vegetarian diet.

- •

The Mediterranean diet is based on the consumption of vegetables, fruits, beans and pulses, nuts, seeds, whole grains; moderate-to-high consumption of olive oil (as the main source of fat); low-to-moderate consumption of dairy products, fish and poultry; low consumption of red meat. This diet has been shown to be effective in improving both blood glucose control and CVRF.14 Compared to the diet based on the American Diabetes Association recommendations, both the traditional and the low-CH Mediterranean diets decreased HbA1c and triglyceridaemia, while only the low-CH Mediterranean diet improved low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol plasma levels at one year of treatment in overweight subjects with DM2.15 A systematic review showed the low-CH diet to be more effective than the low-fat diet in reducing HbA1c in the short term, but not at two years.16 In the multicentre, randomised study, Prevención con Dieta Mediterránea (Predimed) [Prevention with Mediterranean Diet] carried out in Spain in individuals with high cardiovascular risk (CVR), almost half of those diagnosed with DM2 at the beginning of the study showed a reduction in cardiovascular events with a Mediterranean diet supplemented with extra-virgin olive oil or mixed nuts, compared to a lower-fat diet recommended by the American Heart Association.17

- •

The DASH diet, cited in the American Diabetes Association 2020 recommendations,1 highlights the consumption of fruit, vegetables, skimmed milk, cereals and whole grains, poultry, fish and nuts. In addition to reduced sodium, it also includes reduction of saturated fat, red meat, sugar and sugary drinks. However, only one short-term (8 weeks), randomised, controlled study18 among those cited by the American Diabetes Association was carried out in patients with DM2. It found significant improvements in weight, basal blood glucose, blood pressure, high-density and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and HbA1c. A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies that included people with DM2 showed that adherence to the DASH diet was associated with a reduction in cardiovascular events.19

- •

The vegetarian diet model includes lacto-ovo vegetarian, lacto vegetarian, ovo vegetarian and vegan. Observational studies have found a lower prevalence of DM2 in vegetarian subjects than in the general population, while intervention studies carried out in people with DM2 have observed that vegetarian diets lead to a greater reduction in weight, basal blood glucose and HbA1c, and better lipid control than a conventional low-calorie diet, with less reliance on antidiabetic drugs.20 Another systematic review of randomised controlled studies shows that vegetarian and vegan diets improve HbA1c and basal blood glucose in DM2.21

Studies that have attempted to determine the health effects of meal frequency have failed to provide conclusive evidence, regardless of energy and nutrient intake.22 However, other more recent studies support reducing the frequency of food intake.

In one randomised, crossover study in subjects with DM2 treated with oral blood glucose-lowering agents, the distribution of food intake into two larger meals a day (breakfast and lunch) led to benefits in terms of weight and blood-glucose control, compared to distribution into six meals a day.23 In a randomised study in people with DM2 treated with insulin in an undefined regimen, Jakubowicz et al.24 compared the use of an isocaloric diet in three meals versus six meals and found that the diet with three meals led to benefits in terms of weight loss and decrease in HbA1c and blood glucose in general, and also in the reduction of appetite and insulin requirements.

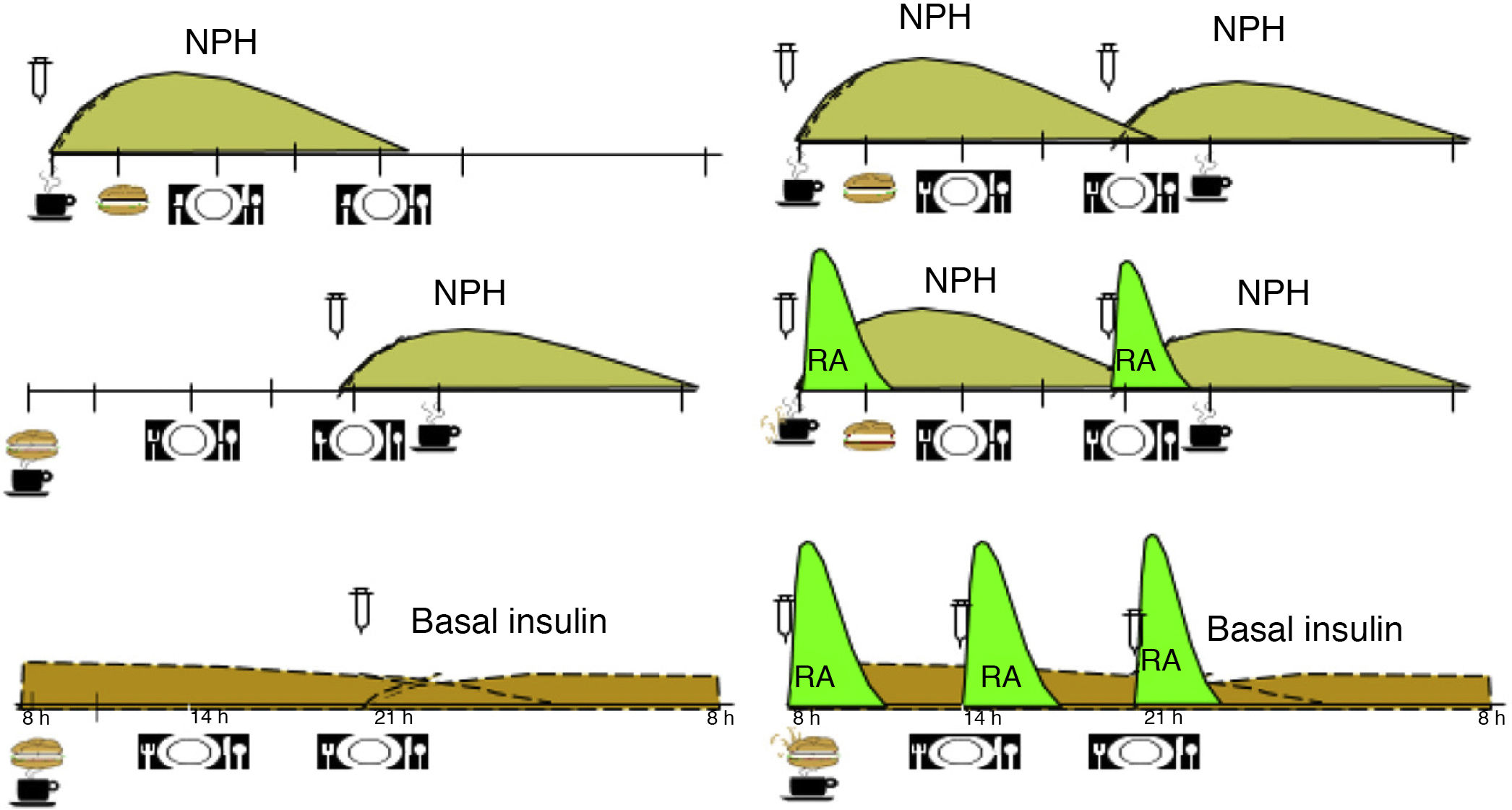

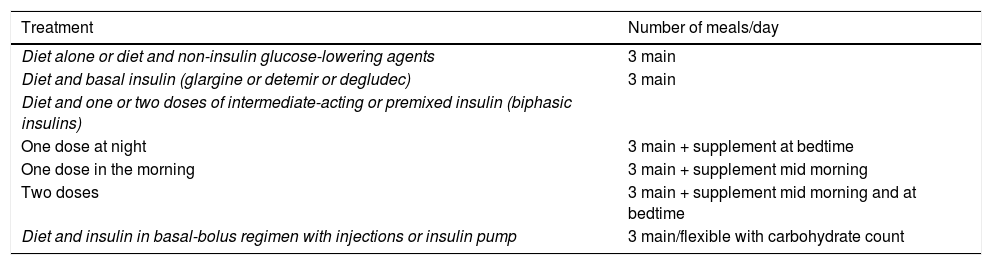

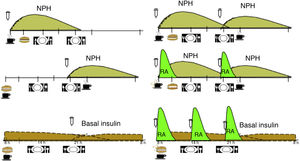

Based on the available evidence, we believe that the distribution of CH should be based on the type of blood glucose-lowering drug therapy, the patient’s blood glucose profile and their habits, and then at a later point adjusted according to blood glucose monitoring results. Table 1 shows an example of meal distribution according to treatment for DM2.25

Initial distribution of carbohydrates by diabetes treatment.

| Treatment | Number of meals/day |

|---|---|

| Diet alone or diet and non-insulin glucose-lowering agents | 3 main |

| Diet and basal insulin (glargine or detemir or degludec) | 3 main |

| Diet and one or two doses of intermediate-acting or premixed insulin (biphasic insulins) | |

| One dose at night | 3 main + supplement at bedtime |

| One dose in the morning | 3 main + supplement mid morning |

| Two doses | 3 main + supplement mid morning and at bedtime |

| Diet and insulin in basal-bolus regimen with injections or insulin pump | 3 main/flexible with carbohydrate count |

Fig. 1 shows the distribution of CH over the day, according to the insulin regimen and action profile.

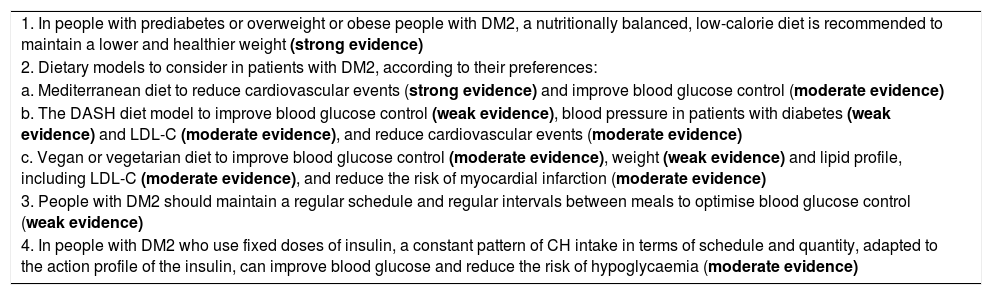

Table 2 shows the dietary treatment recommendations for prediabetes and DM2, with the level of evidence supporting them.

Dietary treatment of prediabetes and type 2 diabetes. Recommendations.

| 1. In people with prediabetes or overweight or obese people with DM2, a nutritionally balanced, low-calorie diet is recommended to maintain a lower and healthier weight (strong evidence) |

| 2. Dietary models to consider in patients with DM2, according to their preferences: |

| a. Mediterranean diet to reduce cardiovascular events (strong evidence) and improve blood glucose control (moderate evidence) |

| b. The DASH diet model to improve blood glucose control (weak evidence), blood pressure in patients with diabetes (weak evidence) and LDL-C (moderate evidence), and reduce cardiovascular events (moderate evidence) |

| c. Vegan or vegetarian diet to improve blood glucose control (moderate evidence), weight (weak evidence) and lipid profile, including LDL-C (moderate evidence), and reduce the risk of myocardial infarction (moderate evidence) |

| 3. People with DM2 should maintain a regular schedule and regular intervals between meals to optimise blood glucose control (weak evidence) |

| 4. In people with DM2 who use fixed doses of insulin, a constant pattern of CH intake in terms of schedule and quantity, adapted to the action profile of the insulin, can improve blood glucose and reduce the risk of hypoglycaemia (moderate evidence) |

Table 3 shows the recommendations for consumption of different foods in the prevention and treatment of prediabetes and DM2, with the level of supporting evidence.

Recommendations for different foods in the prevention and treatment of prediabetes and type 2 diabetes.

| Edible fats |

| Substituting dietary sources of saturated fat for unsaturated fat improves the lipid profile, blood glucose control and insulin resistance26 |

| Moderate evidence |

| The Mediterranean eating pattern has been shown to reduce basal and postprandial blood glucose, improve metabolic control and body weight, and prevent CVD27,28 |

| Moderate evidence |

| The most recommended fat for dressing and daily culinary use is virgin olive oil13,17 |

| Moderate evidence |

| Sunflower, corn and soybean oils undergo oxidative phenomena at high temperatures, with the production of free radicals and other pro-inflammatory molecules, so they should not be used for frying29 |

| Weak evidence |

| Meat |

| Eating meat (no more than four servings per week) does not seem detrimental to CVR and DM2,30–33 although in order to improve the sustainability of the diet, it is a good idea for the population as a whole to reduce their meat consumption and increase consumption of plant -based foods.34 It is best to choose lean cuts of meat and remove the skin and visible fat before cooking |

| Weak evidence |

| The consumption of processed meat is associated with the risk of CVD, colorectal cancer, DM2 and all-cause mortality.30–33 The consumption of sausages and other processed meats is discouraged |

| Moderate evidence |

| Eggs |

| Eating eggs is not harmful and they can be part of a healthy diet. There does not seem to be sufficient evidence to restrict their consumption in order to reduce CVR or improve metabolic control,35–38 although some series limit intake to a maximum of three per week13 |

| Weak evidence |

| Fish |

| Increased consumption of fish contributes to cardiovascular disease prevention. Eating fish or shellfish at least three times a week is recommended, two of these in the form of oily fish39,40 |

| Moderate evidence |

| Dairy products |

| Cheese consumption is not associated with an increase in CVR41,42 |

| Moderate evidence |

| Consumption of dairy products is linked to a reduction in the risk of DM2,43–45 particularly yogurt41,46 |

| Moderate evidence |

| The consumption of dairy products, regardless of their fat content, does not increase CVR.41,42 Evidence does not support limiting the consumption of full-fat dairy products with the aim of reducing the incidence of DM2 or CVD. It is advisable to consume at least two servings of full-fat or skimmed dairy products daily, although it is not advisable to consume dairy products with added sugars. If the aim is to reduce the diet’s calorie content, low-fat or skimmed dairy products are better |

| Moderate evidence |

| Cereals and grains |

| Consumption of whole grains reduces the risk of DM2 and cardiovascular mortality.47–49 The consumption of whole rather than refined grains is recommended |

| Moderate evidence |

| The consumption of white or brown rice was not associated with higher CVR50,51 or an increased risk of DM2, although it was associated with a higher risk of metabolic syndrome51 |

| Weak evidence |

| Beans and pulses |

| As part of a Mediterranean diet, a higher consumption of beans and pulses, and especially lentils, seems to be associated with a lower risk of DM252 |

| Weak evidence |

| Consumption of beans and pulses is associated with lower overall CVR and risk of coronary heart disease.53 A portion of beans or pulses at least four times a week is recommended13 |

| Moderate evidence |

| Root vegetables |

| A moderate consumption of root vegetables of two to four servings a week, preferably baked or boiled, is recommended, limiting commercially processed potatoes with added salt to very occasional consumption.13 Daily consumption of potatoes (especially if fried) can cause an increased risk of DM254,55 |

| Moderate evidence |

| Nuts |

| The consumption of nuts in moderate quantities (30 g/day) has been associated with lower cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.17,56 In people with DM2, the regular consumption of nuts reduces the risk of cardiovascular mortality and all-cause mortality57 |

| Nuts can be recommended for regular consumption to the general population and to subjects with hypercholesterolaemia or hypertension, obesity and/or DM2.13 It is advisable to consume a handful of raw nuts (equivalent to about 30 g) frequently (daily or at least three times a week), avoiding salted nuts |

| Strong evidence |

| Fruit and vegetables |

| Increased consumption of fruit and vegetables is a measure that helps prevent CVD58 |

| It is advisable to eat at least 5 servings of fruit and vegetables a day. Consumption should be varied, avoiding products with added sugars and fats |

| Moderate evidence |

| Chocolate and cacao |

| The consumption of dark chocolate with ≥70% cacao is associated with a reduced risk of AMI, CVA, DM2 and CVD mortality59,60 |

| Most of the cacao-derived products found on the market have added sugars and other fats, and are not recommended |

| Dark chocolate with ≥70% cacao may be consumed in moderate amounts (up to 30 g/day) |

| Weak evidence |

| Processed foods |

| Consumption of ultra-processed foods is associated with an increased risk of DM2, total CVD, coronary and cerebrovascular disease, and all-cause mortality61–63 |

| Ultra-processed foods should be avoided in the diet, and the consumption of fresh, unprocessed or minimally processed foods should be encouraged instead |

| Moderate evidence |

| Salt |

| Too much sodium is associated with chronic kidney disease, obesity, hypertension and cardiovascular mortality64 |

| Daily intake of no more than 2.3 g of sodium is recommended.6 An alternative to salt is to use lemon juice, aromatic herbs, spices or garlic when cooking. It is important to limit consumption of precooked, tinned and salted foods, carbonated drinks and sausages, which all tend to have higher sodium content |

| Moderate evidence |

| Coffee and tea |

| Regular consumption of up to 5 cups per day of coffee (filtered or instant, regular or decaffeinated) or tea (green or black) is beneficial for cardiovascular health65,66 and coffee consumption is inversely associated with the risk of DM267 |

| Coffee or tea with added sugar should be limited as much as possible |

| Moderate evidence |

| Alcoholic drinks |

| Compared to abstinence or excessive consumption of alcoholic beverages, moderate consumption is associated with a reduction in CVR and DM268,69 |

| Moderate evidence |

| The maximum acceptable consumption is one fermented drink per day for women and two for men (one unit being the equivalent of a 330-ml beer or a 150-ml glass of wine)1 |

| Weak evidence |

| Alcohol consumption should not be encouraged in those who are not already accustomed to drinking alcohol. Moreover, no consumption is acceptable in those with a history of diseases that contraindicate alcohol intake (liver disease, hypertriglyceridaemia, history of addictions, etc.)70 |

| Moderate evidence |

| Drinks with added sugars and artificial sweeteners |

| Frequent consumption of beverages with added sugars is associated with an increased risk of obesity, metabolic syndrome, prediabetes and DM271 |

| Strong evidence |

| The substitution of drinks with added sugars for water or unsweetened herbal infusions reduces calorie consumption and the risk of obesity, metabolic syndrome, prediabetes and DM21,13,70 |

| Moderate evidence |

| Herbal, vitamin or mineral supplements |

| There is insufficient evidence to recommend the use of herbal, vitamin or mineral supplements in patients with DM2 who do not have any associated deficiency6 |

| Weak evidence |

Adherence to diet among people with DM2 is very low. In general, as with drug treatment, the factors that contribute the most to a lack of adherence are the deficit in health literacy, the patient’s perception of the disease, the complexity of the treatment, financial limitations, psychological factors and a lack of social support. Table 4 summarises the main factors that hinder adherence to diet in people with DM2.

Factors that hinder adherence to a diet.

| Related to diet design and prescription |

| Use of recommendations whose utility has not been established; for example, blood glucose indexes, “fad” diets, and so on. |

| Use of rigid, monotonous standard diets not adapted to the characteristics of the patient |

| Proposing unrealistic goals |

| Lack of patient involvement in diet design and lack of inclusion of individual preferences |

| Related to healthcare professionals |

| Prescription by healthcare professionals not involved or having no connections with the diabetes team |

| Lack of knowledge and, above all, of conviction about the importance and feasibility of the diet |

| Insufficient patient instruction on the importance, goals and management of the diet |

| Related to the patient and their social environment (emotional aspects) |

| Habit of using food as a coping mechanism |

| Temptations in relation to social events and special meals |

| Difficulty controlling quantities and ingredients |

| No wish to stick to diet |

| Feeling of not being able to eat like non-diabetic people |

| Temptation to stop temporarily (have a break) |

| Giving priority to other aspects they consider to be more important |

| Lack of support/understanding from family and friends |

| Lack of information |

Interventions which contribute to better adherence to diet among people with DM2 are those in which healthcare professionals consider patients’ cultural beliefs, family and social environment, and multifactorial interventions, which include different elements relating to understanding and perception of the disease and diet, and to support and follow-up.72Table 5 shows the strategies to be considered for improving adherence to diet and the level of evidence supporting them.1,7,26

Strategies for improving adherence to diet.

| Measures for improving design and prescription(weak evidence) |

| Simplify the diet. Consider only firmly established recommendations to avoid confusion and contradiction between different prescriptions |

| Design the diet on a personal basis to suit the characteristics of the patient, their diabetes and treatment, and their means and capabilities |

| Create a formal prescription, similar to a pharmacological treatment and integrated with all the other therapeutic measures |

| Select the dietary system or model to transmit the recommendations according to the characteristics of the patient, the treatment for their diabetes, their ability to learn, the clinical goals, etc. |

| Nutrition education(strong evidence) |

| The educational process should be personalised and at least partly carried out on an individual basis by a nurse diabetes educator or dietician experienced in the treatment of diabetes and who forms part of the diabetes team |

| Implementation in three to six sessions over the first six months and then assess the need for additional sessions |

| Behavioural strategies(weak evidence) |

| Show the patient conviction about the importance of diet. Do not play down the importance of diet compared to other therapeutic measures and ask about diet at each visit |

| Set objectives which are accessible in the short term, are flexible and have a good chance of being achieved |

| Avoid talking about failures and focus on what can be done to achieve the goals |

| Commend them for changes in habits, even if blood glucose control, weight or lipid concentration have not changed as much as hoped for |

| Give them praise for having achieved desired goals or simply for positive changes |

| Assess possible obstacles to adherence and encourage the patient to engage in resolving the problem and searching for solutions |

| Encourage the participation of the partner and family members, especially those who prepare the food |

| Ongoing assessment and advice(weak evidence) |

| Nutritional therapy in DM2 is an ongoing process that requires periodic evaluation and support |

| During follow-up, assess adherence to the recommendations and the need to adapt them to changes in the diabetes itself or in the patient’s life |

There is now solid evidence that plant-based eating patterns, essentially the Mediterranean diet, the vegan-vegetarian diet, the DASH diet and the low-CH diet form the substantive basis of treatment to improve control of risk factors and reduce the high cardiovascular morbidity and mortality rates among people with prediabetes or DM2.

In recent years there has been much discussion about the urgent need to transform the food system by adopting a new model which, in addition to the traditional concept of it being healthy for the human population, is also healthy for our planet. In line with the recommendations of multiple corporations and scientifically endorsed by the Lancet Commission, Willett et al. have proposed a “planetary health diet” model, capable of preserving the planetary ecosystem and reducing non-communicable diseases, including DM2.34 This would be a flexitarian (semi-vegetarian) diet, largely consisting of plant-based foods, with fruits, a variety of vegetables, beans and pulses, whole grains, nuts and only small amounts of animal protein. Red meat and its derivatives are a significant source of global warming, land overuse and water consumption. Ultra-processed foods, whether meat-based or otherwise, and the vast majority of precooked foods contain products such as added sugar and trans fats and should be banished from our diet. They should therefore be avoided and we should increase consumption of foods rich in vegetable proteins.

The extent to which food contributes to global warming depends on both its production and transport, so we should eat local, seasonal foods, avoiding those that come from further away. The main therapeutic tool available for improving blood glucose, lipid and blood pressure control and reducing the high associated cardiovascular morbidity and mortality rates among people with prediabetes and DM2 is lifestyle, including regular and sustained physical exercise, and a diet following the recommended guidelines.

FundingNone.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with regard to the content of this article.

Please cite this article as: Pascual Fuster V, Pérez Pérez A, Carretero Gómez J, Caixàs Pedragós A, Gómez-Huelgas R, Pérez-Martínez P. Resumen ejecutivo: actualización en el tratamiento dietético de la prediabetes y la diabetes mellitus tipo 2. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr. 2021;68:277–287.