A mong the several criteria to recognize excellence in medical education, social accountability is probably one of the most important ones. Social accountability is the capacity to respond to society's priority health needs and health system challenges to meet such needs. It emphasizes the potential of medical schools to partner with key stakeholders in the health sector and organize medical education in a way that it has the greatest chances to yield most relevant outcomes and highest impact on people's health.

Entre los diferentes criterios de reconocimiento de la excelencia en la educación médica la responsabilidad social es probablemente uno de los más importantes. La responsabilidad social es la capacidad de responder a las necesidades prioritarias de salud de la sociedad y a los retos del sistema sanitario para atender tales necesidades. Se pone de relieve el potencial que tienen las facultades de medicina para colaborar con las principales partes interesadas en el sector de la salud y para organizar una educación médica que disponga de las mejores opciones para producir resultados más relevantes y el mayor impacto en la salud de las personas.

Excellence is a state beyond the ordinary, which can be assessed either by experts in a given field or/and by potential users of experts’ achievements. In the case of medical education, experts are all those contributing, in and outside the medical school, to the production of what they consider to be the ideal health professional. Users of such a health professional, i.e. patients, health and medical organizations, health insurance schemes, health planners and citizens and society at large, must also be consulted to recognize excellence. This is consistent with the emergence of outcome-based education principles and a more critical appraisal of the contribution of academic institutions to people's health in the wider sense given by WHO's definition: “a complete state of physical, mental and social well being, not just the absence of disease or infirmity”.

Social accountability of medical schools was defined in 1995 by the World Health Organization as: “the obligation to direct their education, research, and service activities toward addressing the priority health concerns of the community, the region, or nation they have a mandate to serve. The priority health concerns are to be identified jointly by governments, health care organizations, health professionals and the public”.1 More recently the Global Consensus for Social Accountability of Medical Schools (GCSA) defines a socially accountable medical school as one that: “responds to current and future health needs and challenges in society, reorientates its education, research and service priorities accordingly, strengthens governance and partnerships with other stakeholders and uses evaluation and accreditation to assess their performance and impact”.2 Increasingly excellence in medical education is being linked to the notion of usefulness and impact, more precisely the notion of making the greatest possible difference on people's health by a more purposeful use of resources and more active collaboration with constituencies that are supposed to benefit from graduates. The social accountability concept is helpful in this context as it aims to plan, implement and evaluate medical education programs. Querying about the impact of a medical education program on people's health leads to two fundamental questions: “Are there medical education programs that have a greater impact on people's health?” and “Can social accountability be measured?”. Satisfactory answers to those questions would reassure seekers of excellence in medical education.

But clarity must be shed on the meaning of health impact. If health is the result of a combination of political, economic, cultural, environmental, social and health care interventions, impact on health should therefore be optimized through a concerted action on those interventions. Also, social accountability implies strong adherence to values that societies regard as crucial in health care delivery, namely: quality, equity, relevance and effectiveness. Medical schools and medical education programs may implicitly adhere to those values, but a clear definition of each is required for a better grasp of implications in serving them.3 Quality in health care is a person-centered care implying that interventions are most relevant and coordinated to serve the comprehensive needs of a patient or a citizen. Equity implies that each person in a given society is given opportunities to benefit from essential health services. Relevance is present when priority is given to most prevalent and pressing health concerns and to most vulnerable individuals and groups in society. Effectiveness is achieved when the best use is made of available resources to the benefit of both individuals and the general population. Obviously for a medical school and a medical education program to contribute to improve those values, solid partnerships must be woven with key health stakeholders in the health system.

Different ways of meeting the social obligationA major expression of the social obligation of a medical school and excellence in medical education is the explicit commitment to produce graduates able to effectively respond to priority health needs and challenges of people and society. There are different ways for fulfilling such a social obligation. For instance, to contribute to equity in health, medical schools may proceed differently. A first example is a medical school offering students a package of courses in anthropology, epidemiology and public health with a focus on determinants of poverty and disparity in health. Field visits and assignments in community settings where disadvantaged people live are also organized with the hope that students may develop an interest to serve in deprived areas when they graduate. A second example is a school engaging students in community based activities from the first year onwards and throughout the curriculum, as one of the school's institutional objectives is to ensure all students acquire well defined competences to care for most vulnerable people. Consistently the assessment of those competences counts for a high mark in the general appraisal of students. The importance of this activity is also highlighted by role models as faculty members from a variety of disciplines commit time and energy to supervise students when assigned in underserved areas. A third example is the one of a school going beyond the above-mentioned commitments by interacting with potential employers of their graduates, in the public or private sector, with the expectation that job opportunities are created in deprived areas and attractive working conditions are offered. Such a school is aware of health system challenges and positions itself as an important actor to influence health policies through active collaboration with key stakeholders.

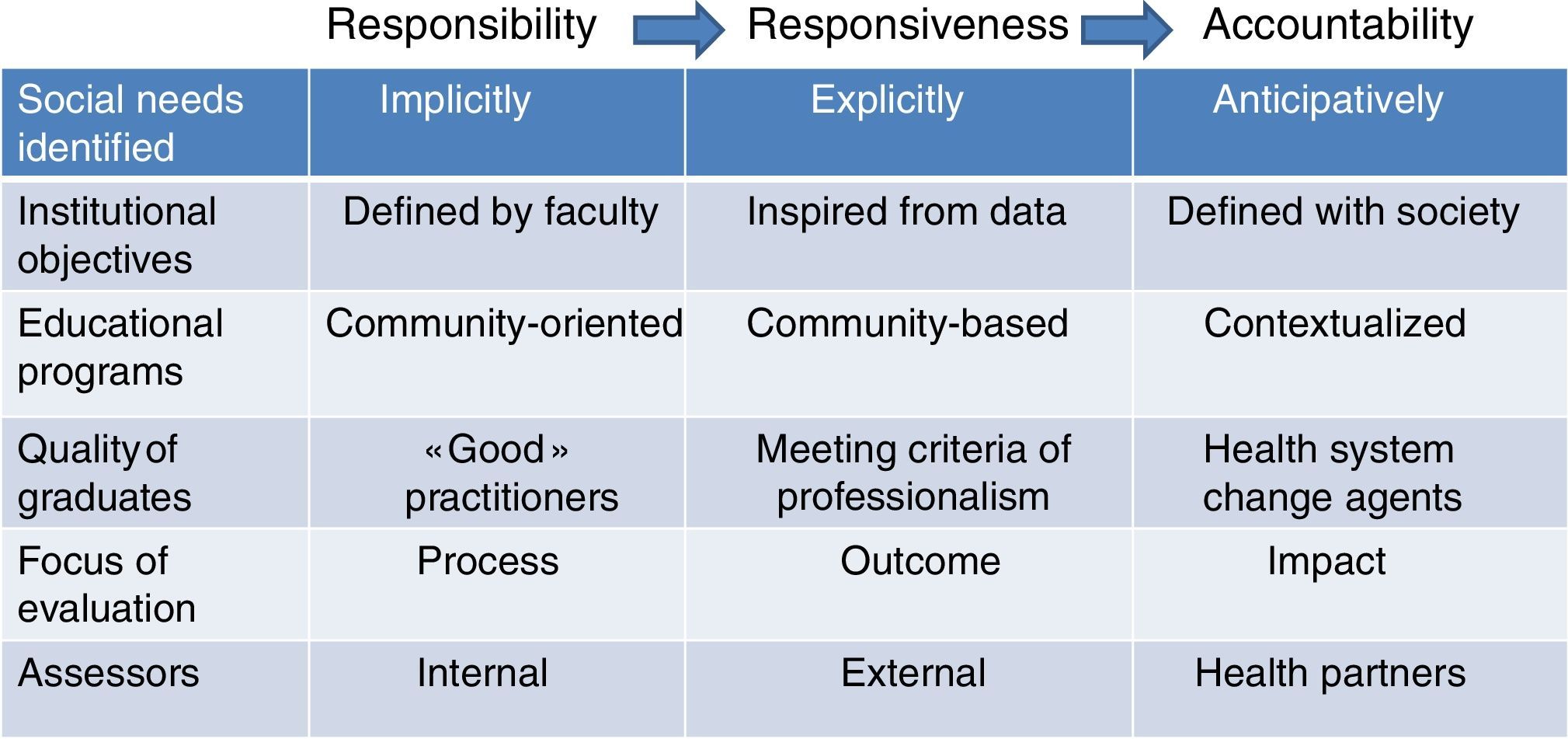

Those examples reflect the different gradients of social obligation. In the first example the school shows “social responsibility” as it implicitly recognizes health disparity issues while in the second example the school demonstrates a desire to act explicitly and purposefully on the issues, a trait of “social responsiveness”. The third example reflects “social accountability” of the school as it takes a set of actions to ensure its graduates are given best chances to practice what they have been prepared for in a real world. By enlarging its scope of interest and following up the opportunity given to graduates in meeting pressing health needs in society, it builds a socially accountable medical education program.

Table 1 illustrates the three different gradients in social obligation, from social responsibility to social responsiveness and social accountability, against six items.4 Under “social responsibility” the aim of the education program is to produce a “good “practitioner, leaving it mainly to the school to define which competences are the most appropriate to meet health needs of patients, while under “social responsiveness”, the education program aims to attain clearly defined competences derived from an objective analysis of people's health needs and grouped under the generic concept of professionalism. It is an important progression in the fulfillment of social obligation from objectives defined by the school to objectives inspired from health data. Under “social accountability”, the ambition of the educational program is to produce health system change agents that would have a greater impact on heath system performance and ultimately on people's health status, implying a quest for innovative practice modalities combining individual and population based services. The program is “contextualized”, meaning taking into account essential factors and challenges to improve health in a given milieu.

Although there is no research to assert that medical schools belong to one of the three categories, intuitively I would tend to believe that 90% may fall under the “social responsibility” column, 9% fall under “social responsiveness” and 1% under “social accountability”. For social accountability to be a strong marker in medical education, the entire medical school has to be committed to make a measurable impact on health in society. Too often, medical educators assume that a curriculum with opportunities for learners to be taught about and exposed to community health situations is sufficient. Although it is a step in the right direction, it needs to be amplified by active and sustainable interaction with potential users of graduates to make a real difference.

Are there medical education programs that have a greater impact on people's health?Let us gauge schools against following three indicators: the retention of graduates in disadvantaged areas, the choice of career as primary care practitioners, practice opportunities in multi-professional teams. These indicators meaningfully reflect social accountability principles: the need for increased density and fair geographical distribution of health worforce, the progress toward universal coverage, the interdisciplinary approach for person centered care, particularly where chronic diseases are prevalent. Four schools in four different continents are put under scrutiny: the Northern Ontario School of Medicine (NOSM) in Canada; the Ateneo de Zamboanga University School of Medicine in South of the Philippines on the island of Mindanao, in Zamboanga; the Tunis medical school in Tunisia; the medical school of Tours in the Loire valley in France.

NOSM was founded in 2006 on the very principes of social accountability. It has two campuses, one in Thunder Bay and one in Sudbury about a thousand kilometers apart and an equal distance North of the city of Toronto, in a vast area known for its nickel mines. Inhabitants belong to an important Indian community and descendants of anglophone and francophone settlers. Governmental authorities decided to create a medical school with hope to improve the health infrastructure with competent health workforce.5 The school's ambition from the start was to reorient is education, research and service delivery programs to meet the priority health needs of local communities. All official documentation describing the school's mission was written in English, French and the local Indian language as part of the school's mission to closely interact with society. The planning, implementation and evaluation of the school's programs are done in close consultation with local authorities and communities to ensure best choices are made to meet the local needs. The educational program is characterized by a longitudinal community immersion of students, learning in groups on real life health cases, tutoring by highly motivated staff to the school's mission. After 10 years of existence, the school is able to claim the high level of retention of graduates, particularly family doctors, increased health coverage and contribution to enhance the local economy by attracting several services and businesses.

In The Philippines, the highly disadvantaged populations in the big island of Mindanao led to the creation of a medical school in Zamboanga. As A WHO staff stationed in the Region I participated to the founding of the school in 1985. Our team consulted the various public and religious authorities and local community chiefs including in the far distant islands of the Borneo sea to seek advice on the creation of the institution and obtain their engagement to recruit students and support them during their medical education course. The deal was that graduates would return to their villages or small towns of origin where health facilities were rare and health indicators poor. From the early start, the Dean and faculty maintain strong links with local public and health authorities and initiated an educational program totally dedicated to respond to local pressing health needs, using the catchment area as a main source of learning opportunities, addressing the various health determinants and implementing effective pedagogical approaches. Two decades later, after consistently implementing a socially accountable education program, the school estimates that it contributed to decrease the infant mortality rates by 90% and to retain 80% of their graduates in local underserved areas, which a great deal would have migrated otherwise either to the capital city or abroad.6 It is a success story for avoidance of brain drain which is prevalent in emerging countries.

The Tunis medical school, which celebrates its 50 years of existence, has been established after the French model under the former colonial ruler. Since independance, significant progress was made regarding educational planning and evaluation and community based education. But a considerable leap toward social accountability was achieved in 2011 and 2012 at time of the “arab spring revolution”. The four medical schools unanimously decided, in close concertation with the Ministries of Health and Higher Education, to address one of the main causes of the national upheaval, that is the flagrant disparity in well being between populations living on the coast and those living inland. This led each school to commit extenting its services to the entire population. In case of the Tunis medical school, the leadership and faculty members animated a national societal dialog with representatives of several health actors including civil society to reform the health system toward greater equity and effectiveness. In practice, the school passed an agreement with health authorities to serve the northern part of the country and its two millions of inhabitants. The school made a special commitment to improve the performance of the first level of care, enlarge health services coverage and prioritize the development of family medicine education program. Continuing medical education sessions are offered on a regular basis in all disciplines to local health professionals. The school consistently refers to the strategic directions of the Global Consensus for Social Accountability of Medical Schools (GCSA) to guide its engagement for a greater impact on society's health. It is too early to assess whether this plan produces the expected outcome and impact but the engagement is promising.

The medical school in Tours is one of the 35 medical schools in France. The dean and his team regularly invite representatives of all major health actors, from health authorities to citizens, of the Region (Region du Centre et du val de Loire) which counts for 3 million of inhabitants to attend meetings on the school premisses, addressing a straightforward question: “What can and should the medical school do for you?”. Each time, priority recommendations are made that engage all stakeholders and interim meetings are held to monitor progress in implementation of those recommendations. Again it is too early to predict whether this initiative will lead to improved coverage, create multi-professional health centers and contribute to greater equity and effectiveness in the health sector, but all ingredients are assembled to design an innovative and purposeful medical education program. Events such as the following are encouraging signs to that effect: the dean receiving a call from a village mayor to help establish a multi-professional health center with assistance of faculty and students; the regional health authority planning cooperative action to attract young graduates to settle in remote areas; health professional associations willing to review policies and practices for task shifting within multi-professional teams.

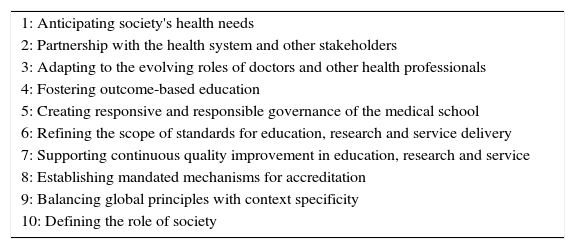

Such developments are facilitated when international or national initiatives make statements in support of social accountability of educational institutions. At international level in 2010, the Global Consensus for Social Accountability of Medical Schools (GCSA) was an outstanding event to stimulate new thinking and efficient strategies to improve the excellence in a medical education program. The GCSA organized over a period of eight months a large three-round Delphi study welcoming and analyzing opinions of representatives of 130 organizations and individual experts from around the world with responsibility for health professional education, professional regulation and policy making, on how best to adapt medical schools and medical education to efficiently address priority health needs of society. A synthetic document was produced composed of 10 sets of strategic directions for action (Table 2).

Ten strategic directions of the Global Consensus for Social Accountability of Medical Schools.

| 1: Anticipating society's health needs |

| 2: Partnership with the health system and other stakeholders |

| 3: Adapting to the evolving roles of doctors and other health professionals |

| 4: Fostering outcome-based education |

| 5: Creating responsive and responsible governance of the medical school |

| 6: Refining the scope of standards for education, research and service delivery |

| 7: Supporting continuous quality improvement in education, research and service |

| 8: Establishing mandated mechanisms for accreditation |

| 9: Balancing global principles with context specificity |

| 10: Defining the role of society |

The 10 strategic directions embrace a system-wide scope of issues from identification of health needs to verification of the effects of medical schools on those needs, all driven by the quest of impact on people's health status. The document is used extensively either at national level or medical school level to create a momentum toward change in medical education programs

Similarly, at country level, medical schools are more prone to reorient their medical educational programs if supported by a national policy. In Canada, for instance, a white paper published by the Health Canada, the federal government health agency, in conjunction with the Association of Faculties of Medicine in Canada suggested social accountability as a vision for medical schools: “Social responsibility and accountability are core values underpinning the roles of Canadian physicians and Faculties of Medicine. This commitment means that, both individually and collectively, physicians and faculties must respond to the diverse needs of individuals and communities throughout Canada, as well as meet international responsibilities to the global community”.7 Further, a paper published by the same national association and based on data obtained from literature reviews, interviews of experts and retreats of researchers considered social accountability on top of the 10 recommendations to orient the future of medical education in Canada.8

How can excellence in a socially accountable medical education program be measured?Standards currently used to assess the quality of medical education, such as the ones of the LCME (Liaison Committee of Medical Education) in North America and the WFME (World Federation for Medical Education) put main emphasis on processes, compared to inputs, outcomes, and impact of medical education programs.9,10 Recently, evaluation instruments of social accountability are beginning to emerge such as the CPU model, an acronym for “Conceptualisation-Production-Usability”, made up of a sequence of parameters exploring more comprehensively the school commitments in planning actions (which is the ideal set of competences for a health professional to fit in an equitable and efficient health system?), in implementing those actions (how is training and learning organized to acquire identified competences?) and in ensuring actions produced the anticipated effects on society (to what extent does the work of graduates improve health system performance and people's health status?).11

The Training for Health Equity network (THEnet), has designed an evaluation framework with benchmarks inspired by the CPU model and field tested it in a sample of medical schools in Australia, Canada, South Africa and The Philippines.12 Each of these schools found the framework effective to identify key factors that affect a school's ability to positively influence health outcomes and health systems performance, also to raise awareness of the issue among students, staff and stakeholders.13 It allowed each school to review their social accountability mission, vision and goals and identify strengths, weaknesses and gaps. In some instance, the CPU model has been used by individual schools having had a long-standing experience of interaction with communities.14

The Association for Medical Education in Europe (AMEE) initiated the ASPIRE project designed to recognize excellence of medical and other health professional schools in certain areas, one of which is social accountability. Criteria for excellence in social accountability are inspired both by the CPU model and the recommendations of the GCSA.15

Conclusion- 1.

Excellence in medical education can be best achieved if a medical school enhances its potential to influence the planning, production and use of graduates in response to priority health needs of people and challenges to health systems.

- 2.

Sustainable excellence in medical education requires efficient partnerships of the medical school with main health actors, such as health policy making bodies, health service organizations, health insurance schemes, professional associations, other health professional schools and community representatives.

- 3.

Benchmarks must be further developed and validated to assess the social accountability of medical schools and medical education programs. Evaluation, and accreditation systems should be revisited to adapt existing standards and include new ones related to outcomes and impact on society.