During 2019 and 2020 a series of meetings over the country were carried out, with the aim of explaining the methodology and criteria for the ellaboration of the recommendations on the use of iPCSK9, published by the Spanish Society of Atherosclerosis (SEA in Spanish). At the end of the meetings, a survey was conducted among the participants, in order to describe the prescription requirements of these drugs in the Spanish regions.

MethodologyButterfly Project was developed by a scientific Committee of experts in lipids. After the ellaboration of the materials for the project, a train the trainers program was carried out, imparted by 17 experts who were the Project coordinators. Later, 16 regional workshops were performed, with the attendance of 169 medical doctors involved in the management of hipercolesterolemia. The attendants responded the survey, where they were asked different questions on the use of iPCSK9 on their clinical practice.

ResultsA high heterogeneity among centers regarding the requirements and difficulties for iPCSK9 prescription was revealed. Twenty one per cent of responders indicated to have low difficulties to prescribe iPCSK9 in their hospitals, whereas 78% found moderate or high difficulties. The difficulties came from burocracy-administrative aspects (18%), restrictions in the indication (41%) and both (38%). In general, the obstacles did not depend on the hospital level, neither the speciality, or the presence of lipid units, although the existance of lipid units was associated with a higher number of patients treated with iPCSK9. The factors which were associated with higher difficulty in the prescription were: the presence of an approval committee in the hospitals, the frequency in the revision of the treatment by hospital pharmacy, the temporal cadence of the prescription, the profile of patients seen and the criteria followed by the specialists for the prescription.

ConclusionThe results show important diferences in the treatment with iPCSK9 in the context of clinical practice in Spain. The analysis of these results will permit to make proposals regarding future actions addressed to reach the equity in the access to iPCSK9 in Spain, with the main aim of maximizing their potential benefit according to the patients profile.

Durante el años 2019 y 2020 se realizaron una serie de reuniones en todo el territorio nacional dirigidas a explicar la metodología y los criterios de elaboración de las recomendaciones sobre la utilización de iPCSK9 publicadas por la Sociedad Española de Arteriosclerosis (SEA). Al final de cada una de las reuniones se realizó una encuesta entre los médicos participantes dirigida a describir los requerimientos de prescripción de estos fármacos en las diferentes regiones españolas.

MetodologíaEl proyecto Efecto Mariposa fue desarrollado por un Comité Científico experto en lipídos. Tras la elaboración de todos los materiales necesarios para llevar a cabo el proyecto, se efectuó una reunión de formadores, impartida por los coordinadores del proyecto, a un total de 17 expertos. Posteriormente, se realizaron 16 talleres regionales con la asistencia de 169 médicos implicados en el manejo de la hipercolesterolemia, los cuales respondieron una encuesta donde se planteaban diferentes cuestiones acerca del uso de los iPCSK9 en su práctica clínica.

ResultadosHubo una gran heterogeneidad entre centros en cuanto a los requerimientos y dificultades para la prescripción de iPCSK9. Un 21% de los encuestados indicaron tener dificultades escasas para prescribir iPCSK9 en su hospital, mientras que el 78% encontraba dificultades moderadas o elevadas. Las dificultades procedían en un 18% de aspectos burocrático-administrativos, en un 41% de restricciones en su indicación, y en un 38% de ambas. En general, los obstáculos encontrados no dependían del nivel del hospital, de la especialidad, ni de la presencia de unidades homologadas de lípidos, si bien la existencia de esta última se asociaba a un mayor número de pacientes tratados con iPCSK9. Los factores asociados con una mayor dificultad en la prescripción fueron: la presencia de una comisión de aprobación, la frecuencia de revisión del tratamiento activo por parte de la farmacia hospitalaria, la cadencia temporal de la prescripción, el perfil de pacientes atendidos y los criterios seguidos por los especialistas para la prescripción.

ConclusiónLos resultados demuestran importantes diferencias en el tratamiento con iPCSK9 en el contexto de la práctica clínica habitual en España. El análisis de estos resultados permitirá plantear en el futuro actuaciones orientadas a la equidad del acceso a los iPCSK9 a nivel nacional, con el objetivo principal de maximizar su beneficio potencial de acuerdo con el perfil del paciente.

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the main cause of death worldwide, accounting for 17.9 million annual deaths and representing 31% of deaths worldwide.1 In Spain, mortality rates are similar to those described worldwide, which in 2018 accounted for 28% total deaths.2,3 For prevention The ESC 2019 guidelines recommend promoting healthy lifestyles and optimal control of risk factors,4 such as elevated low-density lipoprotein (LDL-C) levels, which are a well-established and modifiable risk factor for CVD.5

The proprotein convertase subtilisin kexin type 9 (iPCSK9)6,7 inhibitors have brought about a major change in the management of hypercholesterolaemia.8 By limiting LDL,9 receptor degradation, these drugs have a high lipid-lowering efficacy, which reduces the risk of an atherothrombotic event.8

The effects of iPCSK9 have been studied in clinical trials involving populations with CVD, heterozygous (HFHe) and homozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia (FH), mixed dyslipidaemia and statin intolerance. In all of them, they have demonstrated a marked LDL-C10-lowering effect.10

At the time of the first Therapeutic Positioning Report (TPR) for iPCSK9 inhibitors in 201611,12 there were no morbidity and mortality clinical trials available and therefore it was not known to what extent LDL-C lowering with these drugs was associated with a decrease in cardiovascular risk, a well-established relationship for statins.11 Following this approval by the regulatory agencies, during 2016, the Spanish Society of Atherosclerosis (SEA for its initials in Spanish) established a recommendations document13 with theoretical assumptions on the hypolipidaemic efficacy of iPCSK9 and the expected impact on cardiovascular prevention.14

The FOURIER5 and ODYSSEY OUTCOMES15 studies published in 2017 and 2018, respectively, have thrown light on the effect of the iPCSK9 on cardiovascular morbimortality.

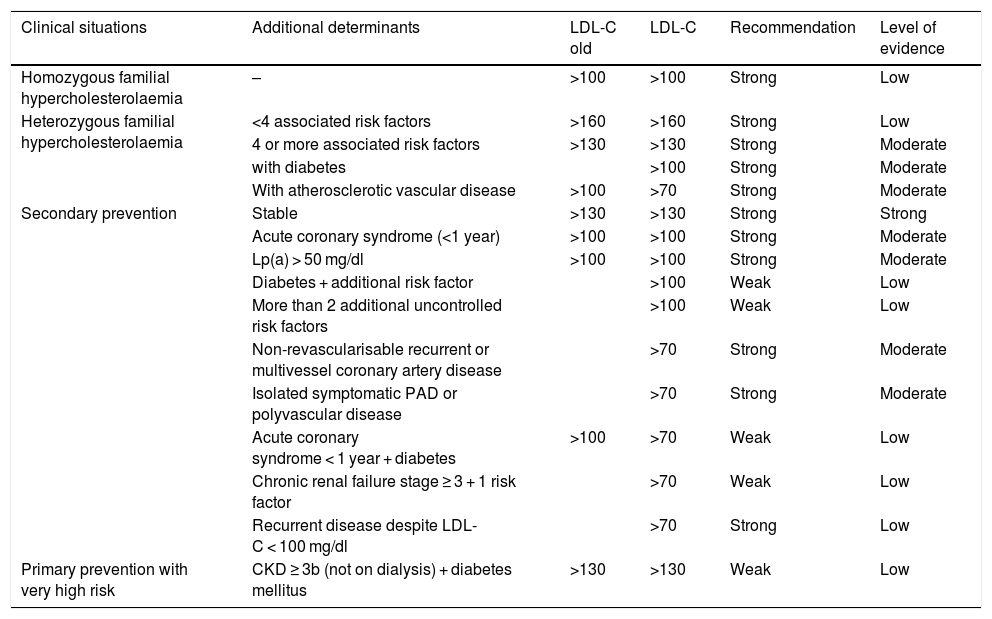

Based on these results, the need arose to update the document published in 2016 on the indications for iPCSK9,13 resulting in 2019 in updated recommendations by a group of experts convened by the SEA8 (Table 1). These recommendations gathered the available evidence and analysed it from a strictly scientific and practical approach, with the aim of identifying those patients in whom treatment would be most efficient.

Recommendations and level of evidence for the prescription of iPCSK9 relating to the clinical situation of the patients and the LDL-C levels.

| Clinical situations | Additional determinants | LDL-C old | LDL-C | Recommendation | Level of evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Homozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia | – | >100 | >100 | Strong | Low |

| Heterozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia | <4 associated risk factors | >160 | >160 | Strong | Low |

| 4 or more associated risk factors | >130 | >130 | Strong | Moderate | |

| with diabetes | >100 | Strong | Moderate | ||

| With atherosclerotic vascular disease | >100 | >70 | Strong | Moderate | |

| Secondary prevention | Stable | >130 | >130 | Strong | Strong |

| Acute coronary syndrome (<1 year) | >100 | >100 | Strong | Moderate | |

| Lp(a) > 50 mg/dl | >100 | >100 | Strong | Moderate | |

| Diabetes + additional risk factor | >100 | Weak | Low | ||

| More than 2 additional uncontrolled risk factors | >100 | Weak | Low | ||

| Non-revascularisable recurrent or multivessel coronary artery disease | >70 | Strong | Moderate | ||

| Isolated symptomatic PAD or polyvascular disease | >70 | Strong | Moderate | ||

| Acute coronary syndrome < 1 year + diabetes | >100 | >70 | Weak | Low | |

| Chronic renal failure stage ≥ 3 + 1 risk factor | >70 | Weak | Low | ||

| Recurrent disease despite LDL-C < 100 mg/dl | >70 | Strong | Low | ||

| Primary prevention with very high risk | CKD ≥ 3b (not on dialysis) + diabetes mellitus | >130 | >130 | Weak | Low |

Adapted from Ascaso et al.8.

Against this backdrop, it was considered necessary to communicate the rationale for the development of these recommendations to healthcare professionals involved in the management of patients with dyslipidaemia. During these meetings, participants were asked to fill in a survey, with the aim of finding out their opinion on the current status of the requirements for requesting the use of iPCSK9 in their workplace and the reality of their clinical practice, for the implementation of the recommendations.

MethodologyThe Butterfly Effect project was developed by a scientific committee (SC) of lipid specialists, the current authors of this manuscript and authors of the updated iPCSK9 recommendations in 2019. Several lipid experts, representatives of the different autonomous communities (ACs), selected for their experience in the management of patients with dyslipidaemias, and collaborating authors of this article, also collaborated in the project.

The aim of the project was to explain and disseminate the recommendations for the use of iPCSK9 to physicians from different ACs involved in the diagnosis and treatment of hypercholesterolaemia. The project was structured in 3 phases: a first start-up phase (July–September 2019), followed by a trainers’ meeting (October 2019) and then 16 regional workshops (November–December 2019).

During the course of the regional workshops, a survey was conducted to learn about and evaluate the use of iPCSK9 in routine clinical practice in the hospitals of the different Autonomous Communities in Spain. The survey was prepared by the ACs and consisted of 48 questions related to the type of patient attended by each participant and their experience in the use of iPCSK9, the requirements of each hospital to approve the prescription of the drugs, as well as factors that, from their point of view, could improve such prescription.

Statistical analysisThe descriptive analysis of the data collected was performed by drawing up frequency tables for nominal variables and measures of central tendency and dispersion for continuous variables, estimating 95% confidence intervals in the case of the latter. In order to evaluate possible correlations between variables, a bivariate analysis was performed for the following variables: existence of a Lipid Unit, difficulty in prescribing iPCSK9, hospital level, existence of an approval committee, speciality and autonomous community, with the other variables included in the questionnaire. For the description of the categorical variables we used the number and percentage per response category, making comparisons between variables using Fisher’s exact test. A significance level of 0.05 was established. The results extracted from this analysis can be found in Appendix B Appendix 2, Supplementary material (Tables S2–S7). Data analysis was performed using the R language, version 3.3.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

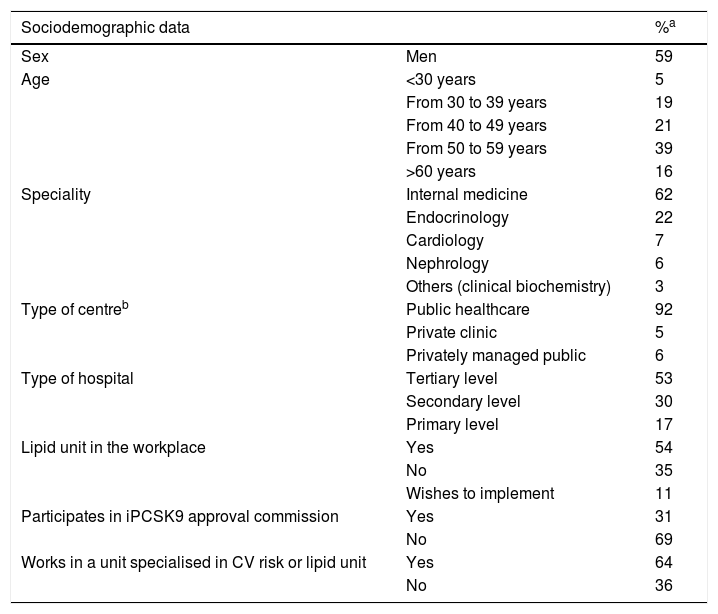

ResultsA total of 169 doctors from different specialties participated in the workshops, 155 of whom (92%) responded to the survey. Table 2 shows the professional and sociodemographic profile of the 155 expert respondents.

Profile of attendees to regional meetings who responded to the survey.

| Sociodemographic data | %a | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | Men | 59 |

| Age | <30 years | 5 |

| From 30 to 39 years | 19 | |

| From 40 to 49 years | 21 | |

| From 50 to 59 years | 39 | |

| >60 years | 16 | |

| Speciality | Internal medicine | 62 |

| Endocrinology | 22 | |

| Cardiology | 7 | |

| Nephrology | 6 | |

| Others (clinical biochemistry) | 3 | |

| Type of centreb | Public healthcare | 92 |

| Private clinic | 5 | |

| Privately managed public | 6 | |

| Type of hospital | Tertiary level | 53 |

| Secondary level | 30 | |

| Primary level | 17 | |

| Lipid unit in the workplace | Yes | 54 |

| No | 35 | |

| Wishes to implement | 11 | |

| Participates in iPCSK9 approval commission | Yes | 31 |

| No | 69 | |

| Works in a unit specialised in CV risk or lipid unit | Yes | 64 |

| No | 36 | |

CV: Cardiovascular.

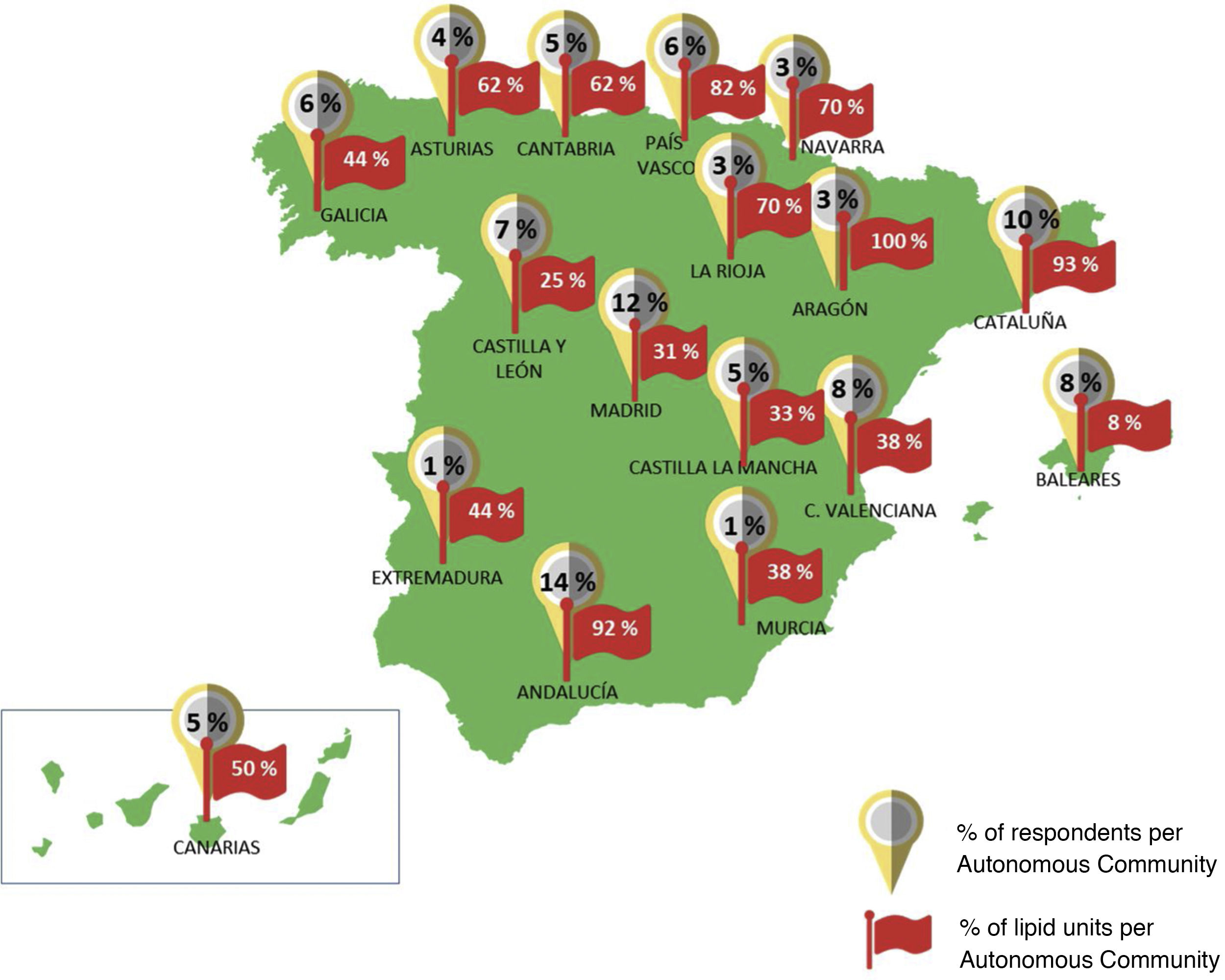

Ninety-two percent of the participants worked in public hospitals throughout the country, with all the Autonomous Communities represented. 53% of the participants reported working in reference or highly specialised hospitals (tertiary level) and 54% reported the existence of an accredited Lipid Unit in their health centres. Fig. 1 illustrates the distribution of these units by Autonomous Community. More than half of the participants (64%) reported being part of a specialised cardiovascular risk unit or Lipid Unit and 31% participated in an iPCSK9 committee in their hospital. Most of the experts were specialists in Internal Medicine (62%) and Endocrinology (22%), and to a lesser extent in Cardiology (7%), Nephrology (6%) or other specialities (3%).

Percentage of participants who responded to the survey and percentage of existing lipid units in each Autonomous Community (hospitals with lipid units/total hospitals in the Autonomous Community of the survey participants). Rounded percentages are shown. The exact percentages of Lipid units for each region are listed in Appendix B Table S9 of the Supplementary material, Appendix 2.

Thirty-six percent of participants cared for more than 10 patients with HFHe per month, compared to 94% and 84% who cared for more than 10 patients per month with established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease or high-risk primary prevention patients, respectively. The majority of these patients were followed by specialists in Internal Medicine and Lipid Units (Appendix B Appendix 2, Table S1 Supplementary material). Ninety-nine percent of the respondents stated that biologic drugs were available at their workplace. Eighty-seven per cent had both evolocumab and alirocumab available and 80% of them could choose the iPCSK9 they considered most appropriate for their patients. In 53% of cases, approval for use was assessed by a specific hospital committee. Thirty-four per cent of respondents indicated that renewal of the iPSCK9 prescription had to be requested by the physician on a monthly basis, while in other cases this time cadence was bimonthly or quarterly (26%), semi-annually (13%) or annually (13%). Similarly, patients were required to pick up their medication from the hospital pharmacy on a monthly (44%), bimonthly or quarterly (37%) or biannual (6%) basis. When picking up medication at the pharmacy, 55% of the cases were checked to ensure that statin or ezetimibe prescriptions were picked up and patients' compliance was assessed. In 67% of the cases, the pharmacy checked compliance with the data in the medical report and in 12% of the cases the pharmacy checked whether the patient was an active smoker.

In terms of prescribing volume, 57% of participating physicians had more than 10 patients on iPCSK9, 35% had less than 10 patients, and the remaining 8% had no patients treated with iPCSK9. Among the reasons that could explain the differences in the number of patients treated could be non-medical barriers to prescribing. In this regard, 21% of respondents reported few difficulties in prescribing iPCSK9, compared to 78% who reported moderate or high difficulties in prescribing – the remaining 1% did not answer this question. The reasons for these difficulties were mainly administrative bureaucratic issues (18%), prescribing restrictions (41%) or both (37%).

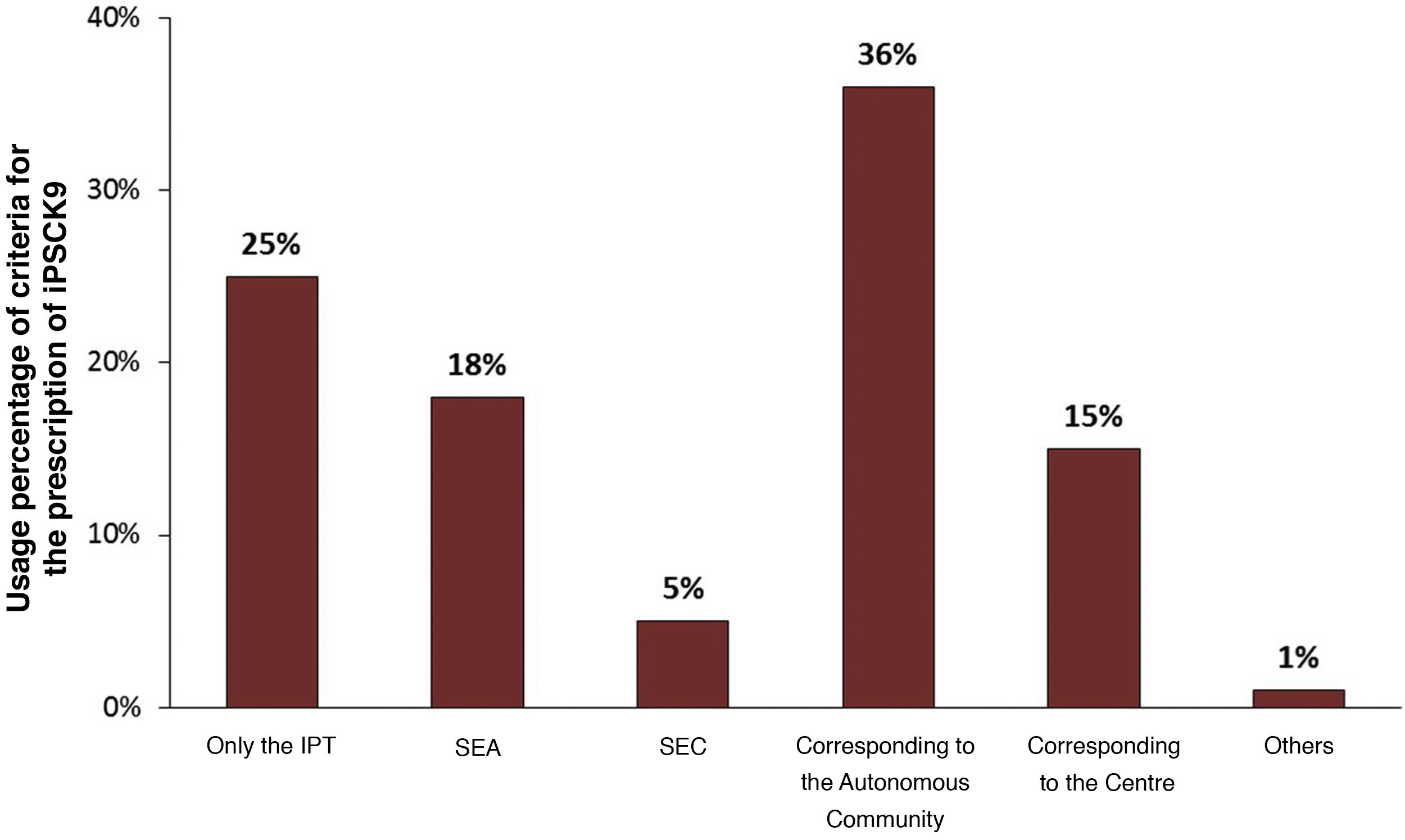

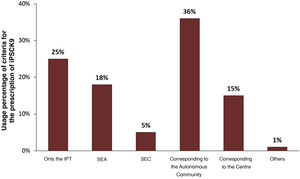

With regard to prescribing restrictions, differences could be identified between the main prescribing criteria followed in the hospitals of the surveyed physicians. As shown in Fig. 2, the main criteria used, apart from the TPR, were those established by the autonomous community (36%) and those recommended by the guidelines of the SEA and the Spanish Society of Cardiology (SEC) (23%). The majority of the doctors, 74%, stated that the criteria contemplated in the TPR did not seem adequate, thus justifying the search for complementary information from other sources. However, 25% of the professionals assumed that only the TPR criteria would be considered.

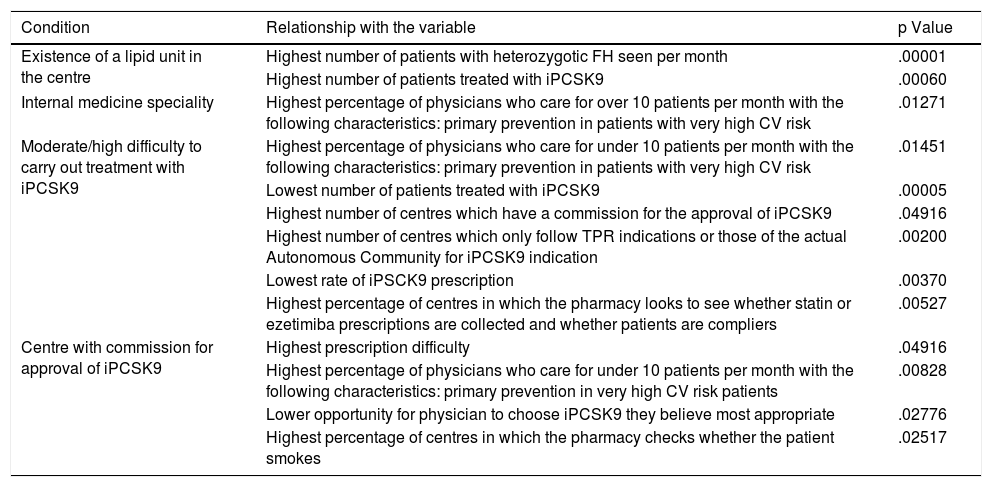

The degree of difficulty in prescribing iPCSK9 was related to the existence of an approval committee and the indication criteria required for prescribing this class of drugs (Table 3). While the existence of an approval committee made prescribing difficult, it was not a limiting factor in deciding which drug was most appropriate for the patient. The difficulty in prescribing, however, was related to the number of patients treated with iPCSK9.

Results of the bivariate statistical analysis.

| Condition | Relationship with the variable | p Value |

|---|---|---|

| Existence of a lipid unit in the centre | Highest number of patients with heterozygotic FH seen per month | .00001 |

| Highest number of patients treated with iPCSK9 | .00060 | |

| Internal medicine speciality | Highest percentage of physicians who care for over 10 patients per month with the following characteristics: primary prevention in patients with very high CV risk | .01271 |

| Moderate/high difficulty to carry out treatment with iPCSK9 | Highest percentage of physicians who care for under 10 patients per month with the following characteristics: primary prevention in patients with very high CV risk | .01451 |

| Lowest number of patients treated with iPCSK9 | .00005 | |

| Highest number of centres which have a commission for the approval of iPCSK9 | .04916 | |

| Highest number of centres which only follow TPR indications or those of the actual Autonomous Community for iPCSK9 indication | .00200 | |

| Lowest rate of iPSCK9 prescription | .00370 | |

| Highest percentage of centres in which the pharmacy looks to see whether statin or ezetimiba prescriptions are collected and whether patients are compliers | .00527 | |

| Centre with commission for approval of iPCSK9 | Highest prescription difficulty | .04916 |

| Highest percentage of physicians who care for under 10 patients per month with the following characteristics: primary prevention in very high CV risk patients | .00828 | |

| Lower opportunity for physician to choose iPCSK9 they believe most appropriate | .02776 | |

| Highest percentage of centres in which the pharmacy checks whether the patient smokes | .02517 |

The Table shows the relationships between the different variables that were statistically significant (p value <.05). The data used for this analysis is described in the Appendix B Tables S2–S7 of the Supplementary material, Appendix 2.

A positive correlation was observed between the existence of lipid units, the number of patients treated with iPCSK9 and the number of patients seen with a diagnosis of HFHe (Table 3). Specifically, in centres with these units, 70% of the specialists had more than 10 patients treated with iPCSK9, while only 42% of the specialists in centres without these units had more than 10 patients treated with iPCSK9. However, the fact of having a Lipid Unit did not influence the difficulty encountered in prescribing, the existence of an approval committee, the prescription requirements, or the criteria required for approval.

For a better implementation of the SEA recommendations in their workplace, 68% of the respondents proposed the elaboration of a joint report by lipid experts justifying the importance of following the recommendations; 43% suggested the updating of clinical practice guidelines, another 43% saw the need for training for the training of hospital specialists and 38% believed that the creation of Lipid units in hospitals without such a unit could help in this regard.

DiscussionIn recent years, a large body of scientific evidence has been generated on the benefit of achieving LDL-C control targets. Pivotal clinical trials with iPCSK9, FOURIER with evolocumab5 and ODYSSEY OUTCOMES with alirocumab15 have provided robust evidence on the benefit of these drugs, particularly in specific patient subgroups. The insights provided by these studies have led to updated recommendations on the use of iPCSKs.8

In order to contextualise the use of iPCSK9s in the different areas of the Spanish healthcare system, a survey was conducted on the use of iPCSK9s in real clinical practice. Among the participants in this survey, there was a predominance of specialists in Internal Medicine, possibly because this speciality covers the 2 population targets for which the indication of iPCSK9 is approved: that of genetic dyslipidaemias, which shares patients with Endocrinology, and that of secondary prevention, which shares patients with Cardiology and often receives from other specialties, such as Neurology and Vascular Surgery.

The vast majority of respondents (78%) agreed that they encountered moderate to high difficulties in prescribing iPCSK9 in their hospitals. This fact is relevant given that the lower the difficulty, the higher the prescription of iPCSK9 and vice versa, the higher the prescription, the better the administrative requirements for the physician. This difficulty was independent of the hospital level, the prescriber’s speciality, the type of patients seen or the existence of a Lipid Unit in the centre. On the other hand, the doctors who described greater ease of prescribing reported that in their hospital there was no drug approval committee, they could prescribe them over longer periods of time, they were not so closely monitored for compliance with the other lipid-lowering drugs and they more frequently followed the SEA’s prescribing recommendations. In short, it appears from the data obtained that the prescription of iPCSK9 is higher if the hospital has a Lipid Unit (essentially because a higher volume of HF patients are seen and there is probably greater awareness of the relevance of dyslipidaemia) and if it does not have a specific monitoring committee (which facilitates prescription).

Due to the sample size, a detailed statistical approximation of the differences between different ACs is not possible. However, given that the distribution of FH patients is expected to be similar throughout the country, the presence of specialised units seems to be a determining factor in the detection of a higher proportion of patients with FH and a more appropriate use of the intensive lipid-lowering treatment that these patients require.

Prescribing restrictions were also pointed out as a conditioning factor for prescribing. Seventy-five percent of the specialists felt that the TPR criteria were outdated at the time of the survey, as they did not incorporate key information from the most relevant studies assessing the cardiovascular protective effect of iPCSKs9. In fact, the TPR served as a single reference document in 25% of respondents. In addition, some ACs established more restrictive criteria than those of the TPR. The new evidence has led the European Medicines Agency to approve in 2018 and 2019 an extension of the indications for evolocumab16 and alirocumab17 respectively, including the indication of vascular risk reduction in adults with established atherosclerosis. In the same vein, the European ESC/EAS 2019 guidelines increased the indication recommendation for IPCSKs9 in very high-risk patients4 from level IIB to level IA. The Ministry of Health has recently updated the TPRs for both drugs.18,19 The Ministry of Health extensively reflects the SEA recommendations for the use of iPCSK9 including risk stratification considerations according to absolute risk and LDL-C levels, which would justify the use of iPCSK9 on the basis of maximum benefit. Paradoxically, the updated TPR leaves the approved funding conditions unchanged: patients with HFHe or in secondary prevention in whom LDL-C > 100 mg/dl persists despite the use of the highest tolerated statin dose. Detailed analysis of the main subgroups of the FOURIER and ODYSSEY OUTCOMES studies shows that there are patients with very high absolute risk in whom iPCSK9 treatment may be justified with LDL-C levels below 100 mg/dl, as they have a reasonably low NNT (5-year NNT < 25) but are excluded from funding in the restrictive interpretation of TPRs. From a clinical, but also cost-effectiveness point of view, the funding of some of these patient groups should be reconsidered.

Apart from these official documents, 18% of the participants recognise that they use the recommendations of the SEA as the main reference of the Spanish scientific society for their clinical decision-making. The lower follow up of the SEC recommendations may be justified by the higher proportion of Internal Medicine specialists among the respondents and by their (later) publication date.

In this regard, almost all participants agreed that the prescription of iPCSK9 should take into account the NNT to avoid a cardiovascular event.

ConclusionsThe use of iPCSK9 in Spain shows a very heterogeneous profile in different ACs. The prescription of iPCSK9 presents with important limitations from an administrative point of view and due to prescription restrictions. In general, the use of iPCSK9 is more widespread in hospitals and Autonomous Regions with SEA Lipid Units, probably in relation to greater recognition and better follow-up of patients with FH. A wider dissemination of SEA recommendations may contribute to improve the appropriate use of IPCSKs9. The update of the iPCSK9 TPR is a step forward in the rational use of these drugs but has fallen short of incorporating cost-effectiveness and reduced NNT criteria for some patient groups with particularly high absolute vascular risk into the funding criteria.

FinancingThis had financial funding from AMGEN.

Conflict of interestsDr. Guijarro declares having received support from Amgen for this project; and fees from consultations and presentations from Amgen, Sanofi, Ferrer, Rubió and Daichi-Sankyo.

Dr. Civeira declares having received support from Amgen for this project; fees for being a speaker and member of advisory boards for Amgen and Sanofi.

Dr. López-Miranda declares having received fees from consultations and presentations from Amgen, Sanofi, Laboratorios Ferrer and Laboratorios Esteve; support to attend meetings with Amgen, Sanofi and Laboratorios Ferrer; and has participated on Advisory Boards of Amgen and Sanofi.

Dr. Masana declares having received fees for consultations and presentations from Amgen, Daiichi, Amarin, Sanofi, Novartis, Amryt, Servier and Milan.

Dr. Mostaza declares having received support from Amgen for this project; and fees for consultations and presentations for Amgen, Sanofi, Novartis and Daichi-Sankyo.

Dr. Pedro-Botet declares having received fees as a speaker for MSD, Amgen, Daiichi Sankyo and Sanofi; fees as expert witness for Amgen.

Dr. Pintó declares having received support from Amgen for this project; subsidies or contracts from Ciber-ISCIII and FIS; fees as consultant or speaker for Almirall, Laboratiorios Rubió, Amgen, Akcea, Mylan-Viatris, Sanofi, Servier, Sobi and Ferrer; fees as a member of the Advisory Boards of Pfizer, Amgen, Laboratorios Rubió, Sanofi and Ferrer.

Dr. Valdivieso declares having received support from Amgen for this project; and fees for consultations and presentations for Amgen, Sanofi, Novartis, AMARIN, Akcea, Ferrer and Daichi-Sankyo.

The authors wish to thank the contribution from the experts who completed the survey in the different regional workshops.

Dr. Marisa Abinzano, Dr. Mar Alameda, Dr. Belén Alemany, Dr. Fátima Almagro, Dr. Núria Alonso, Dr. Luis Miguel Álvarez, Dr. Raimundo Andrés, Dr. Rosa Argüeso, Dr. Diana Ariadel, Dr. Sergio Arnedo, Dr. Miren Arteaga, Dr. Erika Ascuña, Dr. Ángel Asenjo, Dr. José Carlos Baena, Dr. Néstor Báez.

Dr. Cristina Baldeón, Dr. Ángel Ballesteros, Dr. Diego Bellido, Dr. Elda Besada, Dr. Benito Blanco, Dr. Irene Bonig, Dr. María Bonilla, Dr. Miguel Ángel Brito, Dr. Alejandro Caballero, Dr. José Manuel Cabezas.

Dr. Jesús Cantero, Dr. Marta Casañas, Dr. Miguel Castro, Dr. Susana Clemos, Dr. Arturo Corbatón, Dr. Miguel Ángel Corrales, Dr. Sandra de la Roz, Dr. Alejandra de Miguel, Dr. José Antonio Díaz, Dr. Ignacio Díez, Dr. Carlos Dorta, Dr. Valeriu Epureanu, Dr. Verónica Escudero, Dr. Margarita Esteban, Dr. Aida Fernández, Dr. Esther Fernández, Dr. José María Fernández, Dr. Jordi Ferri, Dr. Maria Fullana, Dr. Esperança Garcés, Dr. Antonio García, Dr. Bernardo García, Dr. Iluminada García, Dr. Jaime García, Dr. Lourdes García, Dr. Pablo García, Dr. Rocío García, Dr. Rogelio García, Dr. Juan Girbés, Dr. Ángela Gómez, Dr. Gonzalo Gómez, Dr. Marta Gómez, Dr. Blanca González, Dr. Esther González, Dr. José Manuel González, Dr. Juan González, Dr. Pilar González, Dr. Jordi Guerrero, Dr. Maite Guimón, Dr. Ramón Guitart, Dr. Liliana Gutiérrez, Dr. Juan José Guzmán, Dr. Luis Irigoyen, Dr. Sergio Jansen, Dr. Ana Isabel Jiménez, Dr. Manuel Jiménez, Dr. Cristina Ligorria, Dr. Cesar López, Dr. José Antonio López, Dr. Manuel Macía, Dr. María Marqués, Dr. Jorge Marrero, Dr. David Martí, Dr. Guillermo Martín, Dr. Ignacio Martín, Dr. Mercedes Martín, Dr. Miguel Martín, Dr. Iratxe Martinez, Dr. Ceferino Martínez, Dr. Fernando Martínez, Dr. Juan Carlos Martínez-Acitores, Dr. Laia Matas, Dr. Marta Mauri, Dr. Juan Diego Mediavilla, Dr. Araceli Menéndez, Dr. Javier Mora, Dr. Francisco Morales, Dr. Miriam Moreno, Dr. Carlos Morillas, Dr. Daniel Mosquera, Dr. Isabel Muinelo, Dr. Nuria Muñoz, Dr. Juan Navarro, Dr. Josefina Olivares, Dr. Evelyn Ortiz, Dr. Raúl Parra, Dr. Juan Blas Pérez, Dr. Leire Pérez, Dr. Rosa Pérez, Dr. Jaume Pons, Dr. Montse Prados, Dr. Inés Prieto, Dr. Nuria Puente, Dr. José Puzo, Dr. Marta Robledo, Dr. Antonio Robles, Dr. María Rosario Robles, Dr. Antonio Rodriguez, Dr. Gemma Rodríguez, Dr. Patricia Rodríguez, Dr. Belén Roig, Dr. Joan Rosal, Dr. Pedro Jesús Rozas, Dr. Eloy Rueda, Dr. María Pilar Sáez, Dr. Ramón Salcedo, Dr. María Isabel Salgado, Dr. Zaida Salmón, Dr. Justo Sánchez, Dr. Rosa María Sánchez, Dr. Carlos Santiago, Dr. Alfons Segarra, Dr. Ignacio Segura, Dr. Ángel Sevillano, Dr. Cristina Sevillano, Dr. Cristina Soler, Dr. Carmen Suárez, Dr. Lorena Suárez, Dr. Manuel Suárez, Dr. Christian Teijo, Dr. Raimundo Tirado, Dr. Joan Torres, Dr. Ferran Trías, Dr. Juan Ramón Urgeles, Dr. Nuria Valdés, Dr. José María Vaquero, Dr. Luis Vigil, Dr. Irama Villar and Dr. Alberto Zamora.

The Butterfly Effect Project is a study by the Spanish Society of Atherosclerosis (SEA) and had the collaboration of AMGEN (Beatriz Cuende and Santiago Villamayor), who the authors thank for their continuous support. Thanks also to GOC Health Consulting (Natalia Framis and Annalisa Pérez) for their support ad collaboration in methodological advice and the redaction of this manuscript.

Agustín Blanco, Ángel Brea, José Luis Díaz, Jacinto Fernández, José Luis Hernández, Gabriel Inclán, Carlos Lahoz, Joan Lima, Amparo Marco, José Alfredo Martín, Luis Masmiquel, José Pablo Miramontes, Ovidio Muñiz, Núria Plana, julio Sánchez, Juanjo Tamarit, Francisco Villazón.

The names of the collaborative authors and participants of the Butterfly Effect Project are listed in Appendix A.

Please cite this article as: Guijarro C, Civeira F, López-Miranda J, Masana L, Pedro-Botet J, Pintó X, et al. Situación en 2020 de los requerimientos para la utilización de inhibidores de PCSK9 en España: resultados de una encuesta nacional. Clin Investig Arterioscler. 2022;34:10–18.