Severe hypercholesterolaemia is a major cardiovascular risk factor. Early detection and treatment can reduce the incidence of cardiovascular disease. Given the high prevalence of hypercholesterolaemia in Andalusia, the development of a screening strategy for its detection in Primary Care may be an efficient measure.

ObjectiveTo identify patients in Primary Care with severe hypercholesterolaemia that may increase their cardiovascular risk by reviewing LDL-cholesterol results in computerised laboratory systems.

Material and methodsObservational, retrospective, multi-centre study in 16 hospitals in Andalusia and Ceuta. Anonymous analytical data were acquired from the different laboratory computer systems for the year 2018, and exclusively from Macarena Hospital for the year 2019.

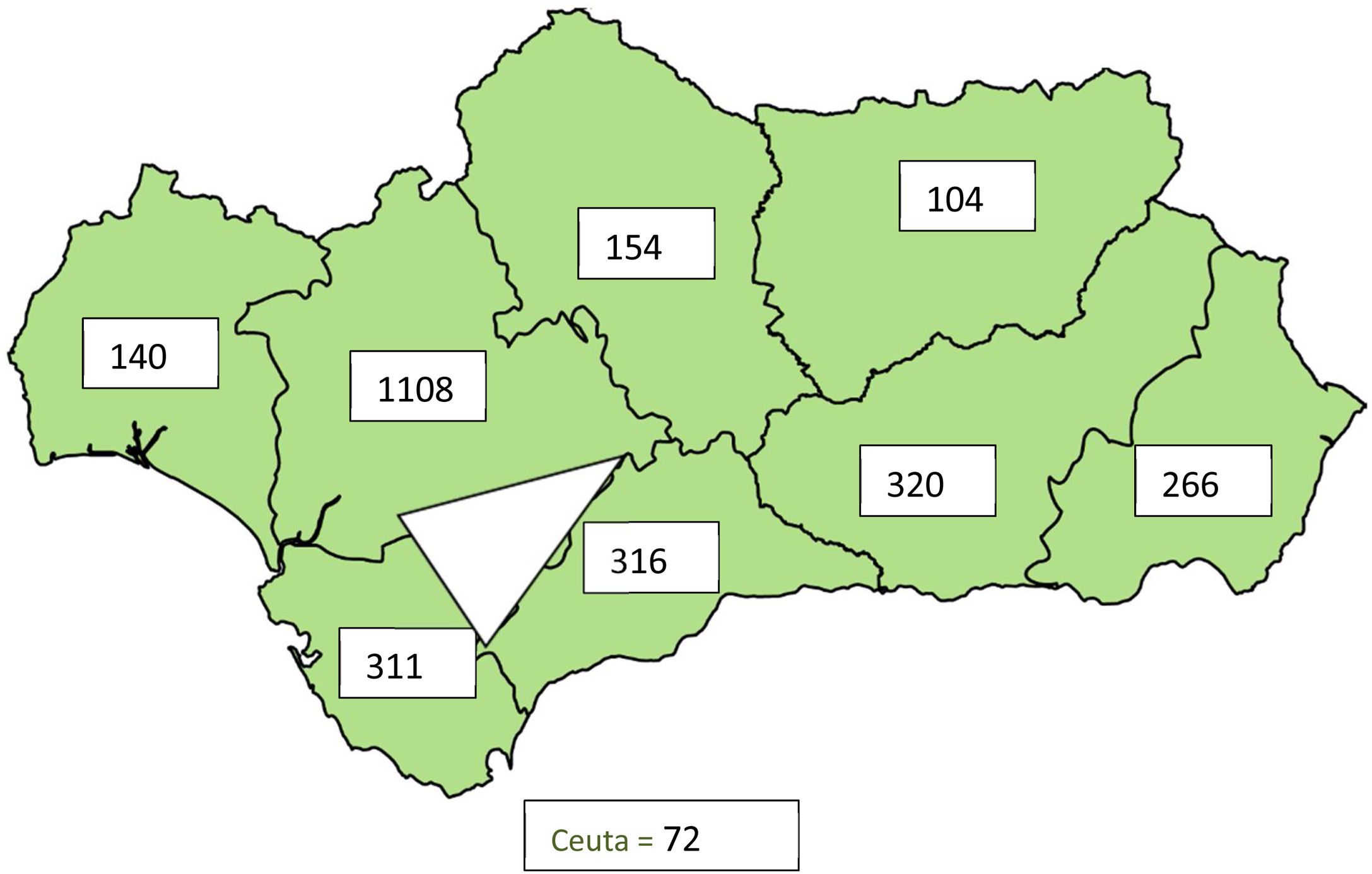

ResultsFrom a total of 1,969,035 determinations on ≥18 years old, 2791 patients (0.14%) were detected with LDL-cholesterol >250 mg/dl and from a total of 2.327.211 determinations studied in children under 18 years old, 3804 patients (0.16%) were detected with LDL-cholesterol >135 mg/dl. The highest incidence of possible genetic hypercholesterolaemia in adults corresponded to the province of Seville with 23.6 cases/1000 determinations, while in minors, the highest incidence corresponded to the province of Cadiz with 75 possible cases/1000 determinations. A geographical triangle of greater prevalence is observed between the provinces of Seville, Huelva and Cadiz.

ConclusionsThe development of a screening strategy using a computerised review of LDL-cholesterol in Primary Care detects a large number of subjects with severe hypercholesterolaemia that could benefit from an early intervention.

La hipercolesterolemia severa es un importante factor de riesgo cardiovascular. Su detección precoz y tratamiento puede reducir la incidencia de las enfermedades cardiovasculares. Dada la alta prevalencia de hipercolesterolemia en Andalucía, el desarrollo de una estrategia oportunista para su detección en atención primaria puede ser una medida eficiente.

ObjetivoIdentificar pacientes en atención primaria con hipercolesterolemias severas que puedan incrementar su riesgo cardiovascular mediante una consulta del colesterol- LDL al sistema informático de laboratorio.

Material y métodosEstudio observacional, retrospectivo, multicéntrico, en 16 hospitales de Andalucía y Ceuta. Se adquirieron datos analíticos anonimizados de los diferentes sistemas informáticos de laboratorio del año 2018 y exclusivamente del Hospital Virgen Macarena para el año 2019.

ResultadosDe un total de 1.969.035 determinaciones ≥ 18 años se detectaron 2.791 pacientes (0,14%) con colesterol-LDL > 250 mg/dl, y en menores de 18 años, sobre un total de 2.327.211 determinaciones estudiadas, se detectaron 3.804 pacientes (0,16%) con colesterol-LDL > 135 mg/dl. La mayor incidencia de posibles hipercolesterolemias genéticas en adultos correspondió a la provincia Sevilla con 23,6 casos/1.000 determinaciones, mientras que en menores la mayor incidencia correspondió a la provincia de Cádiz, con 75 posibles casos/1.000 determinaciones. Se observa un triángulo geográfico de mayor prevalencia entre las provincias de Sevilla, Huelva y Cádiz.

ConclusionesEl desarrollo de una estrategia oportunista mediante consulta informática del colesterol-LDL en atención primaria detecta un gran número de sujetos con hipercolesterolemias severas que se podrían beneficiar de una intervención precoz.

Vascular diseases are one of the main causes of morbidity and disability, making them the primary cause of death in Western countries.1 Specifically, the autonomous community of Andalusia presents with the highest standardised mortality rates by age in Spain, rising to rates that surpass the national mean (35% of deaths).2

According to a preliminary assessment of the Dreca 2 study (evolution of the cardiovascular risk in the Andalusian population over the last 16 years [1992–2007]),3 70% of Andalusians aged between 20 and 74 years present with at least one cardiovascular risk factor (CRF) which could be related to the said high mortality rates. Also, 31.3% are smokers, 29.9% have high blood pressure, 47.8% have dyslipidaemia and 29.5% obesity.

The lack of control of these CRFs in the population and the biochemical markers for assessing compliance with objectives, according to the estimated risk, may be responsible for the development of most cardiovascular events. A wide base of scientific evidence has shown that excess blood cholesterol, especially cholesterol attached to low density lipoproteins (LDL-c), and the group of apolipoprotein B-containing lipoproteins, are an essential cause of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (CVD).4,5 The EUROASPIRE V study reflected that only a third of patients with coronary episodes complied with LDL-c,6 objectives and that such a disappointing fact was due to the low adherence to treatment and to underprescribing of maximum dose hypolipidaema treatments. The lack of obtainment of lipid objectives in patients with high RCV is alarming. It not only correlates with the high rate of CVD recurrences, but also carries high financial and social costs.7 Scientific evidence has steadfastly shown that the reduction of LDL-c (LDL cholesterol) does not solely depend on hypolipidaemia treatment, but on the degree of reduction reached with said treatment, including the control of other dietary factors, progressing from the concept of high intensity statin usage to the use of the term hypolipidaemia therapy.8 This association would generate a reduction of CVD mainly in those with higher decreases of LDL-c9 and greater benefits, even in the population over 75 years of age.

Early detection of CVD and good control or eradication of CVR should be considered one of the priorities or basic pillars in primary prevention of CVD, since these are also priority objectives of the health strategies developed by the World Health Organisation.

Given the high prevalence of CRF in Andalusia, its associated mortality, lack of data and the increase in health costs involved, the results of an observational study are provided, together with a proposal for a new strategy which seeks to comply with the World Health Organisation recommendations on reducing mortality.

ObjectivesTo identify patients with severe hypercholesterolaemias in primary care resulting from a computer based consultation of the LDL-c parameters from different laboratory computerized systems.

Material and methodsA observational, retrospective, multicentre, cross-sectional study conducted in the University Hospital Ingesa in Ceuta and in the 16 hospitals of Andalusia: Hospital Nuestra señora de Valme (Seville), Hospital de Torrecárdenas (Almeria), Hospital Universitario Clínico San Cecilio (Granada), Hospital Reina Sofía (Cordoba), Hospital de Puerto Real (Cadiz), Hospital Regional Universitario (Malaga), Hospital Juan Ramón Jiménez (Huelva) and Hospital Infanta Elena (Huelva), Hospital Universitario Virgen Macarena (Seville), Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío (Seville), Hospital Nuestra Señora de la Merced (Osuna), Hospital Puerta del Mar (Cadiz), Complejo Universitario de Jaén, Hospital San Juan de Dios (Bormujos-Seville), Agencia sanitaria Costa del Sol (Marbella, Malaga).

Data was obtained from the following consultation to each laboratory computerised system (LCS). Only the data from the Hospital Virgen Macarena are from the year 2019.

- -

Number of patients ≥18 years and LDL-c > 250 mg/dl between 1st January and 31st January 2018.

- -

Number of patients <18 years and LCL-c > 135 mg/dl between 1st January and 31st January 2018.

The cut-off point selected for patients ≥18 years of LCL-c > 250 mg/dl was calculated to be correct as a value which discriminates patients with possible severe hypercholesterolaemias, since according to the MED PED criteria for diagnosis of familial hypercholesterolaemia, a patient with LDL-c = 250−329 mg/dl would get a minimum of 5 points. Also, this value obtained high sensitivity and specificity in the Civeira el at.10 study, where they compared the genetic diagnosis with the clinical diagnosis in familial hypercholesterolaemia (FH). LDL-c > 250 mg/dl is also a value which is over double that of the therapeutic objective for low risk patients in primary prevention, according to the latest recommendations of the European Society of Cardiology.11

In the case of minors the cut-off point of LDL-c > 135 m/dl was chosen, according to the criteria selected in the DECOPIN study corresponding to the 95 normality percentile.12

ResultsOut of a total of 1,969,035 determinations ≥18 years 2791 patients (.14%) were detected with LDL-cholesterol >250 mg/dl and in <18 years, out of a total of 2,327,211 determinations analysed 3804 patients (.16%) were detected with LDL-cholesterol >135 mg/dl. The highest incidence of possible genetic hypercholesterolaemias in adults corresponded to the province of Seville with 23.6 cases/1000 determinations, whilst in minors the greatest incidence corresponded to the province of Cadiz, with 75 possible cases/1000. A geographic triangle was observed of greater prevalence between the provinces of Seville, Huelva and Cadiz, both in adults and children.

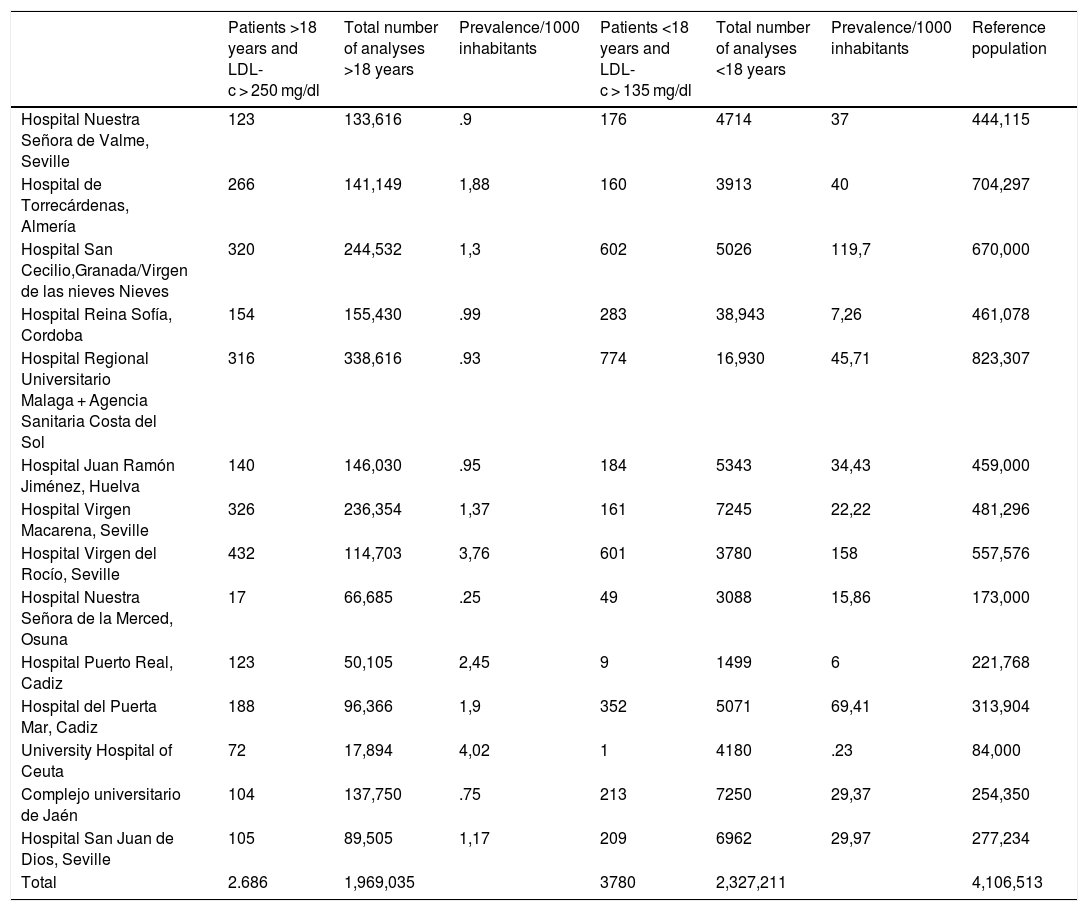

Table 1 shows the number of patients ≥18 years and LDL-c > 250 mg/dl and the number of patients <18 years and LDL-c > 135 mg/dl classified by participant hospital centre, number of total LDL-c determinations made in that period by each hospital centre, the prevalence for each 1000 determinations and the number of patients who comprised that area of reference. The number of cases obtained is related to the number of hospitals that participated in each province, the number of analytical tests requested and the total of the population covered.

Number de patients ≥18 years and cholesterol attached to low density lipoproteins >250 mg/dl and number of patients <18 years and cholesterol attached to low density lipoproteins >135 mg/dl classified by hospital centres, number of analyses with cholesterol attached to low density lipoproteins in 2018 and reference population.

| Patients >18 years and LDL-c > 250 mg/dl | Total number of analyses >18 years | Prevalence/1000 inhabitants | Patients <18 years and LDL-c > 135 mg/dl | Total number of analyses <18 years | Prevalence/1000 inhabitants | Reference population | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital Nuestra Señora de Valme, Seville | 123 | 133,616 | .9 | 176 | 4714 | 37 | 444,115 |

| Hospital de Torrecárdenas, Almería | 266 | 141,149 | 1,88 | 160 | 3913 | 40 | 704,297 |

| Hospital San Cecilio,Granada/Virgen de las nieves Nieves | 320 | 244,532 | 1,3 | 602 | 5026 | 119,7 | 670,000 |

| Hospital Reina Sofía, Cordoba | 154 | 155,430 | .99 | 283 | 38,943 | 7,26 | 461,078 |

| Hospital Regional Universitario Malaga + Agencia Sanitaria Costa del Sol | 316 | 338,616 | .93 | 774 | 16,930 | 45,71 | 823,307 |

| Hospital Juan Ramón Jiménez, Huelva | 140 | 146,030 | .95 | 184 | 5343 | 34,43 | 459,000 |

| Hospital Virgen Macarena, Seville | 326 | 236,354 | 1,37 | 161 | 7245 | 22,22 | 481,296 |

| Hospital Virgen del Rocío, Seville | 432 | 114,703 | 3,76 | 601 | 3780 | 158 | 557,576 |

| Hospital Nuestra Señora de la Merced, Osuna | 17 | 66,685 | .25 | 49 | 3088 | 15,86 | 173,000 |

| Hospital Puerto Real, Cadiz | 123 | 50,105 | 2,45 | 9 | 1499 | 6 | 221,768 |

| Hospital del Puerta Mar, Cadiz | 188 | 96,366 | 1,9 | 352 | 5071 | 69,41 | 313,904 |

| University Hospital of Ceuta | 72 | 17,894 | 4,02 | 1 | 4180 | .23 | 84,000 |

| Complejo universitario de Jaén | 104 | 137,750 | .75 | 213 | 7250 | 29,37 | 254,350 |

| Hospital San Juan de Dios, Seville | 105 | 89,505 | 1,17 | 209 | 6962 | 29,97 | 277,234 |

| Total | 2.686 | 1,969,035 | 3780 | 2,327,211 | 4,106,513 |

It was confirmed that the hospitals with the largest healthcare areas presented with a higher number of analytical determinations. The highest prevalence for each 1000 determinations, if a comparison is made for each hospital centre in adults, was recorded in the University Hospital of Ceuta, followed by the Hospital Virgen del Rocío and Puerto Real, similar in Torrecárdenas and Puerta del Mar. Lower prevalence was in the Hospital de San Celicio, Hospital de Reina Sofía and Juan Ramón Jiménez, in Huelva. In the case of the minors, the highest prevalence for every 1000 determinations was in the Hospital Virgen del Rocío, Puerta del Mar and the University Hospital of Malaga and the lowest in the Hospital de Reina Sofía, in that of Ceuta and in that of Puerto Real.

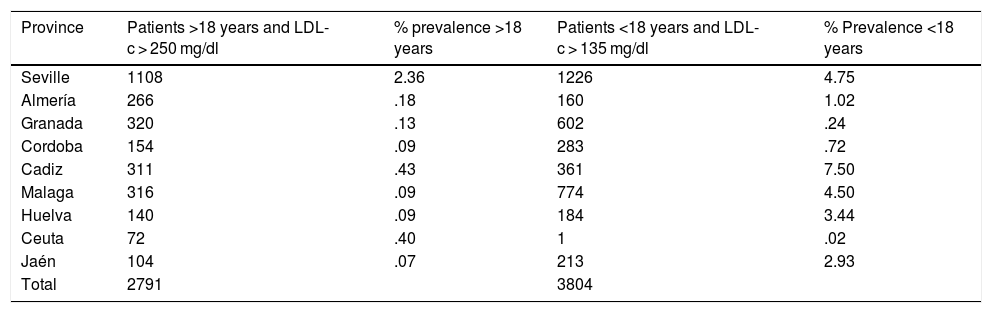

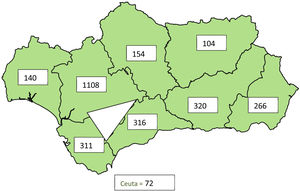

Table 2 shows the number of patients ≥18 years and LDL-c > 250 mg/dl and number of patients <18 years and LDL-c > 135 mg/dl classified by provinces of cases detected according to the number of LDL-c determinations. The province of Seville is the one which presents with a higher and significant percentage in adults, 2.36% compared with other provinces, secondly Cadiz with .43% and third Ceuta with .40%. In the case of minors the provinces with the highest prevalence was Cadiz, with 7.5%, followed by Seville and Huelva, forming a geographical triangle of risks from childhood.

Number of patients ≥18 years and cholesterol attached to low density lipoproteins >250 mg/dl and number of patients <18 years and cholesterol attached to low density lipoproteins >135 mg/dl classified by provinces, total number of analyses which contain lipid profile and prevalence.

| Province | Patients >18 years and LDL-c > 250 mg/dl | % prevalence >18 years | Patients <18 years and LDL-c > 135 mg/dl | % Prevalence <18 years |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seville | 1108 | 2.36 | 1226 | 4.75 |

| Almería | 266 | .18 | 160 | 1.02 |

| Granada | 320 | .13 | 602 | .24 |

| Cordoba | 154 | .09 | 283 | .72 |

| Cadiz | 311 | .43 | 361 | 7.50 |

| Malaga | 316 | .09 | 774 | 4.50 |

| Huelva | 140 | .09 | 184 | 3.44 |

| Ceuta | 72 | .40 | 1 | .02 |

| Jaén | 104 | .07 | 213 | 2.93 |

| Total | 2791 | 3804 |

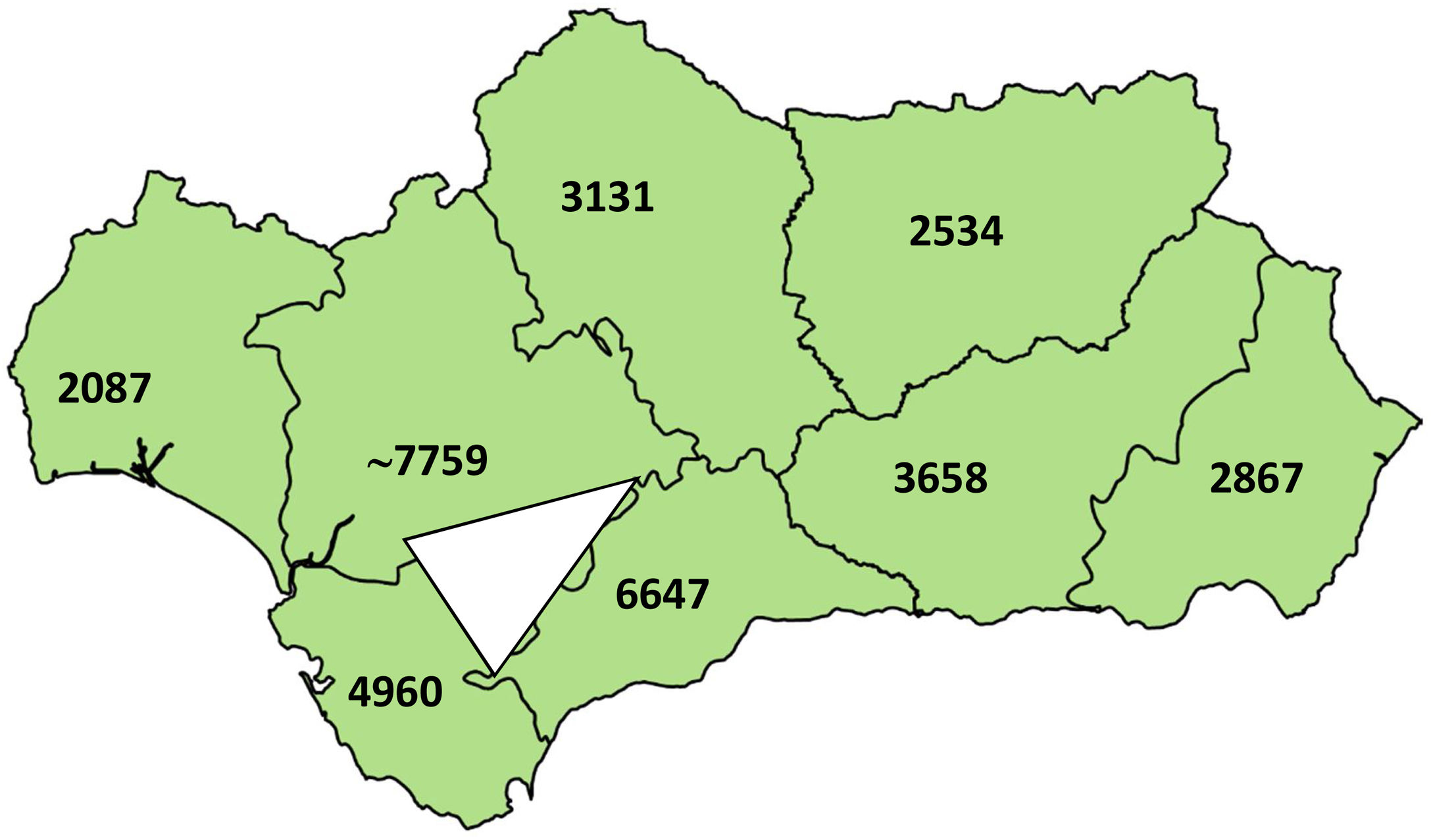

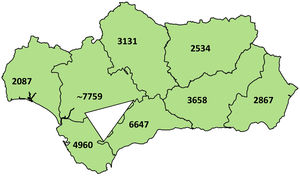

Fig. 1 graphically represents the number of patients >18 years and LDL-c > 250 mg/dl by province, and a geographical triangle aimed at greater prevalence. Fig. 2 shows a graphic representation of possible patients affected by FH according to the province of Andalusia in 2019, with an estimated prevalence of 1/250 and a triangle of higher prevalence. For this estimation the 2019 population data for each province were obtained from the national institute of statistics,13 and were divided by 250 in each province, according to estimated prevalence (1/250). This geographical triangle was similar to the data obtained in Fig. 1.

Assessment of cardiovascular risk in the Andalusian population may be quantified using different biochemical parameters which are determined in routine clinical laboratories. Analysis of these parameters may serve as a base for the design of different RVC prevention strategies from primary care. There are not many studies in the Autonomous Community of Andalusia which currently assess the prevalence of severe hypercholesterolaemias or the degree of dyslipidaemia with the biochemical LDL-c parameter. The Dreca3 study used the total cholesterol parameter equal to or higher than 240 mg/dl, obtaining a 37.8% of dyslipidaemia applying this criteria, including possible patients with high HDL cholesterol which could falsify the results. It has been extensively reported that in the south of Spain there are areas with higher cardiovascular risk. Benacheñ et al. reported a surprising geographical grouping which accounted for 8% of the Spanish population and represented approximately a third (2884 deaths) of the excess of total mortality.14

With the selected criteria for adults, 2791 analytical data were obtained with LDL-c > 250 mg/dl, a considerable number of patients on whom we applied the criteria from the Dutch Network of Lipid Clinics15 to diagnose familial hypercholesterolaemia, due to this concentration where they already had a “possible” clinical diagnosis (3–5 points) just by the determination of LDL-c. If we also add clinical criteria, suspected diagnosis of a highly prevalent, genetically based disease with a 50% penetration to descendants could increase. In the case of minors the estimation by score has not been validated.

One “weakness” of the study detected is that in the LCS consultation secondary causes in children and adults were not ruled out. The reason for not ruling out these secondary causes comes from obtaining a real representative sample of lipid changes of the selected population, in order to include those significant secondary lipid changes which also confer the patient with a certain vascular risk and should be under accurate clinical and therapeutic management. These concentrations which have tremendously increased, refer to both primary and secondary causes, and reflect the lack of effectiveness in treatment prescription and the low adherence or absence of compliance with therapeutic objectives for low risk patients in other diseases which indirectly enhance RCV. The second weakness is that several analytical results have been included which correspond to the same patient within the study period. These data could suggest the low adherence to treatments, or the absence of complying with therapeutic objectives.

It is appreciated that in the hospitals with the highest volume of samples, or in those where primary care analytical tests are centralised, the number of patients LDL-c > 250 mg/dl increased compared with the others, with the most outstanding laboratories being those of Malaga and Granada, and in the province of Seville the Hospital Virgen Macarena and Virgen del Rocío. These are also Hospitals with long-standing Lipid Units accredited by the Spanish Society of Arteriosclerosis.

In the case of patients under 18 years of age, a sample of 3804 patients with LDL > 130 mg/dl was obtained. It is important to look in greater detail at this data and the ratio of LDL-c concentration increase and/or deposited in arteries/time of exposure. The risk differs if we consider a raised cholesterol in a patient aged 60 years than 60 years of raised cholesterol. A lifetime exposure to high LDL cholesterol levels leads to a notably higher risk of cardiovascular disease, ranging between 2 and 26 times, depending on the levels of cholesterol, and the years of exposure to it.16 If we look at this criterion we observe a geographical triangle in the provinces of Seville, Cadiz and Huelva of higher prevalence and Malaga. One study in a nearby autonomous community assessed the prevalence of hyperlipidaemia in children and teenagers in the province of Caceres and used the same criterion in Extremadura, exposing 569 individuals (26.46%), with this being more frequent in women at 28.93%, compared with 24% in men (p < .05).17 The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health of U.S.A.18 guideline has proposed several cut-off points in the plasmatic lipid concentration for the evaluation of CVD risks in children, regarding levels of CT, LDL-c, HDL-c and triglycerides, in which differences are described according to the age, sex and pubertal development that would be interesting to apply in the study in the said geographical area. There are no recent studies in Andalusia with which we may make comparisons. As shown in Fig. 2 it could be evaluated that by estimating the Andalusian population of 2019, the existence of a triangle was confirmed of greater prevalence of lipid changes between the provinces of Seville, Cadiz and Malaga, oriented towards Granada. The said estimated triangle coincides with that obtained geographically and in orientation. The provinces acquired the following order of possible affects in FH according to the prevalence of 1/250: Seville > Malaga > Cadiz > Granada > Cordoba, Almeria > Jaén and Huelva with a lower prevalence. At present there is no exclusively Andalusian record of patients with severe hypercholesterolaemias or familial hypercholesterolaemia and the genetic characterisation is low, like in the other autonomous communities. Studies shows just 6% of patients with genetic characteristics in Spain.19 Records do exist of data obtained from routine medical reviews of an Andalusian cohort, where greater prevalence in a higher number of CRF stands out in the provinces of Cordoba and Jaén, and a lower prevalence in a higher number of CRF in Huelva and Almería.20

As a screening strategy to increase early detection of severe hypercholesterolaemias of possible genetic origin, we propose the use of alerts to the physician requesting routine analytical tests. This strategy would be endorsed by recent recommendations of the consensual document of the European Atherosclerosis Society and the European Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine21 in which, in its ninth recommendation, it proposes the generation of alerts when results are extremely higher in order to begin a study of the patient. Furthermore, the elimination of normal LDL-c levels would be of great use, replacing them by recommendations of the therapeutic objectives depending on patient risk and type of prevention.

ConclusionsThe development of a screening strategy using computerized review of LDL cholesterol in primary care detects patients with severe hypercholesterolaemias, and a geographical area in Andalusia of higher prevalence that could benefit from early intervention.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Begoña Gallardo Alguacil, Esther Roldán Fontana, María Lourdes Diez Herranz, Salomé Hijano Villegas, Elena Bonet Struch, Ignacio Vázquez Rico, María Luisa Hortas Nieto, María Cinta Montilla López, Joaquín Bobillo Lobato, Manuel Rodríguez Espinosa, José Vicente García Lario, Cristina Romero Baldonado and Jacobo Diaz Portillo.

The names of the vascular risk workgroup of Andalusia are contained in Appendix A.

This communication was presented at the 32nd National Congress of the SEA-Valencia from the 12th to 14th June 2019 and was awarded with the prize for the best communication of the area/primary care topic/epidemiology.

Please cite this article as: Arrobas Velilla T, Varo Sánchez G, Romero García I, Melguizo Madrid E, Rodríguez Sánchez FI, León Justel A, et al. Prevalencia de hipercolesterolemias severas observadas en los distintos hospitales de Andalucía y Ceuta. Clin Investig Arterioscler. 2021;33:217–223.