The objective of the study is to describe the clinical and epidemiological characteristics of our patients with elevated Lp(a).

Materials and methodsA descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted on 316 patients with elevated Lp(a) (>125 nmol/L) in a random sample between January and August 2022. We measured epidemiological, anthropometric, clinical and laboratory variables (lipid metabolism parameters, carbohydrates and hormones).

ResultsMean age of our sample subject’s was 59 ± 15 years with 56% males. The average BMI was 27.6 kg/m2 (71% with elevated BMI). Elevated waist circumference was observed in 54.1% of men and 77.8% of women. 48% had hypertension, 30.7% had diabetes mellitus and 91.5% dyslipidemia. Only 39.7% of the patients had never smoked.

The mean values of total cholesterol were 158 ± 45 mg/dl, LDL was 81 ± 39 mg/dl, HDL was 53 ± 17 mg/dl, Triglycerides were 127 ± 61 mg/dl, and Lp(a) was 260 ± 129 nmol/l.

Regarding lipid lowering treatment, 89% were on statins, 68.6% on ezetimibe, and 13.7% on PCSK9 inhibitors. 177 patients (57,7%) had established cardiovascular disease (CVD), 16.3% had polyvascular disease, 11.7% had subclinical CVD, and 30.6% had no known CVD. Among patients with established CVD, 174 (98.3%) were on lipid-lowering treatment (97.2% on statins) and 86.4% were on antiplatelet therapy. The mean age of cardiovascular events was 55 ± 12 years in males and 60 ± 11 years in females. 65,1% of female and 56,2% of male patients suffered an early cardiovascular event.

ConclusionsPatients with elevated Lp(a) are at very high cardiovascular risk, particularly for early cardiovascular disease.

El objetivo del estudio es describir las características clínico-epidemiológicas de nuestros pacientes con Lp(a) elevada.

Material y métodosEstudio descriptivo transversal de 316 pacientes con Lp(a) elevada (>125 nmol/l) en una muestra aleatoria entre enero y agosto de 2022, midiendo variables epidemiológicas, antropométricas, clínicas y analíticas (parámetros del metabolismo lipídico, hidratos de carbono y hormonales).

ResultadosLa edad media de los sujetos de la muestra fue de 59 ± 15 años con 56% varones. El índice de masa corporal (IMC) medio fue de 27,6 kg/m2 (71% de IMC elevado). Un perímetro abdominal aumentado en 54,1% de los hombres y 77,8% de mujeres. Un total de 48% con hipertensión arterial (HTA), 30,7% de diabetes mellitus (DM) y 91,5% con dislipemia. Solo 39,7% de los sujetos nunca habían fumado. Los valores medios de colesterol total fueron de 158 ± 45 mg/dL, lipoproteína de baja densidad (LDL) de 81 ± 39 mg/dL, lipoproteína de alta densidad (HDL) de 53 ± 17 mg/dL, triglicéridos (TG) de 127 ± 61 mg/dL y Lp(a) de 260 ± 129 nmol/L. Con respecto al tratamiento hipolipemiante, 89% estaban con estatinas, 68,6% con ezetimiba y 13,7% con los inhibidores de proproteína convertasa subtilisin/kexin tipo 9 (iPCSK9). Un total de 177 pacientes (57,7%) padecían enfermedad cardiovascular (ECV) establecida, de ellos 16,3% enfermedad polivascular. Además, había 11,7% usuarios con ECV subclínica y 30,6% sin ECV conocida. Aquellos con ECV establecida, 174 (98,3%), estaban con terapia hipolipemiante (97,2% con estatinas) y 86,4% antiagregados. La edad media de evento cardiovascular fue 55 ± 12 años en varones y 60 ± 11 en mujeres. Presentando 65,1% de ellas y 56,2% de los hombres un evento cardiovascular precoz.

ConclusionesLos pacientes con Lp(a) elevada son pacientes de muy alto riesgo cardiovascular y en especial de ECV precoz.

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a leading cause of mortality worldwide (17.9 million people annually).1 The role of lipoprotein(a) (Lp[a]) in the formation of the atheromatous plaque that is key to CVD has generated particular interest in recent years.

Approximately one third of the population has elevated Lp(a) levels, which increases their risk of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality by up to 20%.2

In primary prevention, values above the 75th percentile have been associated with an increased risk of developing aortic stenosis (AS)3 and myocardial infarction (MI),4 and above the 90th percentile increases the risk of heart failure.2,5 Levels above the 95th percentile increase the risk of cardiovascular mortality and ischaemic stroke.2,6

In secondary prevention, it is associated with a higher incidence of cardiovascular events, and a linear relationship is found between Lp(a) levels and CVD, after adjusting for low-density lipoprotein (LDL) ranges and lipid-lowering treatment.7

Currently, there is no approved therapy that significantly reduces Lp(a) levels, and therefore these patients must be kept under strict control for other cardiovascular risk factors (CVRFs).

Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 inhibitors (PCSK9i) have been shown to reduce Lp(a) levels significantly, by around 25%–30%,8 although it is not known whether this decrease in Lp(a) contributes to a reduction in ischaemic events.

There are also therapies with molecules called small interfering RNAs that would decrease hepatic production of apolipoprotein A (apo A).9 Some studies with these molecules are very promising, with reductions of up to 80%, almost all subjects maintaining normal Lp(a)10 levels.10

Patients with elevated Lp(a) levels are a subgroup of the population at particular cardiovascular risk (CVR) and therefore current guidelines recommend measuring Lp(a) at least once in a lifetime to adequately stratify individual CVR.2

The aim of the study is to describe our population of patients with elevated Lp(a), analysing anthropometric, clinical, and analytical parameters and their relationship with cardiovascular events.

Material and methodsStudy design and subjectsA retrospective, cross-sectional observational study was designed, selecting patients with elevated Lp(a) (>125 nmol/L)2 in an analysis requested for any reason between 1 January 2022 and 31 August 2022. These service users were provided by the clinical analysis service of the Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre, regardless of the requesting service.

Those who at the time of data collection did not have an electronic medical record or whose records were protected were excluded, resulting in a sample of 316 patients.

The Hospital 12 de Octubre Research Institute approved the study (Appendix A Annex 1) and the researchers agreed to handle patient information in accordance with Organic Law 7/2021 on data protection of 26 May 2021.

Measurements and variablesEpidemiological and anthropometric data such as age (years), sex, height (m), weight (kg), body mass index (BMI) (kg/m2), and abdominal circumference (cm) were collected. BMI categories were established according to standardised cut-off points.11 High abdominal circumference was considered to be greater than 102 cm in men and greater than 88 cm in women.12

The following comorbidities were also analysed: smoking and alcohol use, family history (FH) of CVD, clinically established CVD (stroke, MI, cardiac revascularisation, or peripheral artery disease), subclinical CVD established by imaging, age at first cardiovascular event, considered early in women younger than 65 years and in men younger than 55 years,13 hypertension (HT), diabetes mellitus (DM), and dyslipidaemia, defined as having a medical history or taking medication for these conditions, polyvascular disease (clinical involvement of two or more vascular territories), hepatic steatosis (diagnosed by imaging techniques), systemic autoimmune diseases (SAD), and AS (classified as mild, moderate, and severe according to echocardiographic criteria).

The patients' usual treatment was also assessed: high-potency statins (rosuvastatin 10/20/40 mg or atorvastatin 40/80 mg), other statins (that did not meet the above criteria), ezetimibe, PCSK9i, antiplatelet agents (ASA), anticoagulants (AC), angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, or angiotensin-2 receptor antagonists (ACE inhibitors/ARII), calcium (Ca) antagonists, diuretics, beta-blockers (BB), oral anti-diabetics (OAD), and insulin.

The analytical parameters included haemogram values, lipid metabolism factors such as total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL), LDL, triglycerides (TG), apo A, apo B-100, non-HDL cholesterol, and HDL/TG ratio.

Lp(a) was analysed by particle-enhanced immunoturbidimetric assay on the Cobas c701 analyser (8000 Cobas c701 module) (material number: 05641489001) from Roche Diagnostics.

For carbohydrate metabolism, basal blood glucose (mg/dL), glycosylated haemoglobin (%), insulin resistance index (HOMA), C-peptide, and insulin were included.

Statistical analysisThe results of the descriptive analysis of the sample were presented in relative frequencies (percentages) for qualitative variables and in measures of central tendency and dispersion (mean ± standard deviation [SD]) for quantitative variables.

The X2 test was used to compare qualitative variables and the Bonferroni correction was applied for intergroup comparisons. For quantitative variables, after testing for normality, the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test and the Kruskal-Wallis test with Bonferroni correction were used for intergroup comparisons. The normality test was Kolmogorov-Smirnov. Pearson's correlation coefficient was used as correlation coefficient.

An α statistical significance level was set at .05 for all comparisons. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS 27.0.0, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used for the analysis).

ResultsThe total sample studied was 316 patients with a mean age of 59.5 ± 14.8 years, 56.6% of whom were male. Anthropometric values were collected in 223 users, with a mean BMI of 27.6 ± 5 kg/m2, 26% obese, 45% overweight, 27% normal weight, and 2% underweight.

Abdominal circumference was measured in 153 subjects, with a mean of 95 ± 12 cm in women (70% with increased measurement) and 102 ± 13 cm in men (49% with elevated values). With regard to their health habits, 87% had never consumed alcohol and 39.7% had never smoked.

The clinical-epidemiological data are summarised in Table 1. With regard to CVD, those under 18 years of age were excluded (nine subjects). A total of 30.6% had no previous CVD. Of these, 57.7% (177 patients) had established CVD, of which 16.3% of cases were polyvascular disease and 11.7% subclinical CVD. The mean age at presentation of overall CVD was 57 ± 12 years, 60 ± 11 in females and 56 ± 11 in males, and 39 (65.1%) of the females and 66 (56.2%) of the males had early onset CVD.

Clinical and epidemiological parameters of the total sample.

| Age (years) | 59.5 ± 14.8 |

| Sex | 56.6% male |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.6 ± 5 |

| Abdominal circumference (cm) | 99.8 ± 13 |

| Current smoking habit | 29.2% |

| Previous smoking habit | 31.1% |

| Current alcohol habit | 10% |

| Previous alcohol habit | 3% |

| FH of CVD | 27.8% |

| Clinical CVD | 57.7% |

| Subclinical CVD | 11.7% |

| Age at onset CVD (years) | 57 ± 12 |

| HT | 48% |

| DM | 30.7% |

| Prediabetes | 25% |

| Dyslipidaemia | 91.5% |

| Polyvascular disease | 16.3% |

| Hepatic steatosis | 16.8% |

| SAD | 8.5% |

| AS | 1.6% |

AS: aortic stenosis; BMI: body mass index; CVD: cardiovascular disease; DM: diabetes mellitus; FH: family history; HT: hypertension; SAD: systemic autoimmune disease; SD: standard deviation.

Values expressed in percentages and mean ± SD.

Of the 316 participants in the sample, three had died at the time of the study aged 48, 64, and 66 years, two of them from cardiovascular causes.

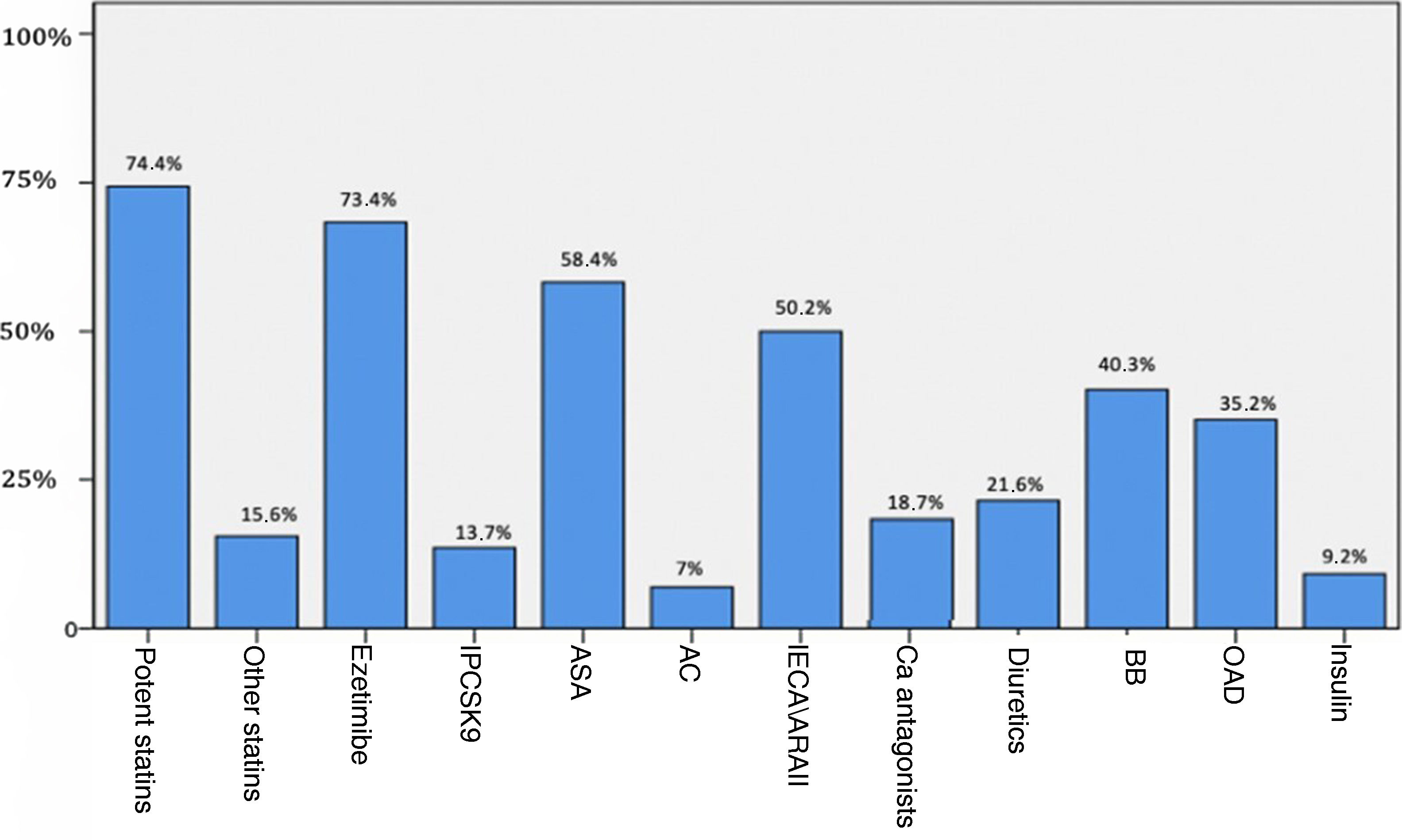

The analytical parameters of lipid and carbohydrate metabolism and insulin resistance are shown in Table 2, and Fig. 1 reflects the previous treatment of the patients at the time of analysis.

Analytical parameters of the total sample.

| Lipid parameters (n = 316) | |

|---|---|

| Total cholesterol | 158 ± 45 mg/dL |

| LDL-C | 81 ± 39 mg/dL |

| HDL-C | 53 ± 17 mg/dL |

| Non-HDL cholesterol | 106 ± 39 mg/dL |

| TG | 127 ± 61 mg/dL |

| Apo A | 140 ± 32 mg/dL |

| Apo B | 75 ± 24 mg/dL |

| Lp(a) | 260 ± 129 nmol/L |

| HDL/TG | 2.7 ± 1.8 |

| Carbohydrate and hormone parameters | |

|---|---|

| Glycosylated haemoglobin (n = 276) | 6.1 ± 1% |

| Glucose (n = 312) | 107 ± 30 mg/dL |

| Creatinine (n = 312) | .91 ± .29 mg/dL |

| Insulin (n = 109) | 13.9 ± 10.4 mg/dL |

| C-peptide (n = 83) | 3.3 ± 2 mg/dL |

| HOMA (n = 100) | 3.8 ± 3.9 |

| Uric acid (n = 181) | 5.1 ± 1.9 mg/dL |

Apo A: apolipoprotein A; apo B: apolipoprotein B; HDL: high-density lipoprotein; HDL-C: high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HDL/TG: high-density lipoprotein to triglycerides ratio; HOMA: insulin resistance index; LDL-C: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; Lp(a): lipoprotein(a); TG: triglycerides.

Values expressed as mean ± SD.

Treatment of subjects at time of the analysis.

ASA: antiplatelet drugs; AC: anticoagulants; ACEI/ARBs: angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers; BB: beta-blockers; Ca: calcio; OAD: oral antidiabetic; PCSK9i: proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 inhibitors.

A total of 177 subjects with clinical CVD were included, with a mean age of 63.9 ± 11 years and a mean age at onset of CVD of 56.4 ± 11 years, 67.2% of whom were male. Of the subjects, 62.7% had HT, 39% had DM, and 33.9% had pre-diabetes.

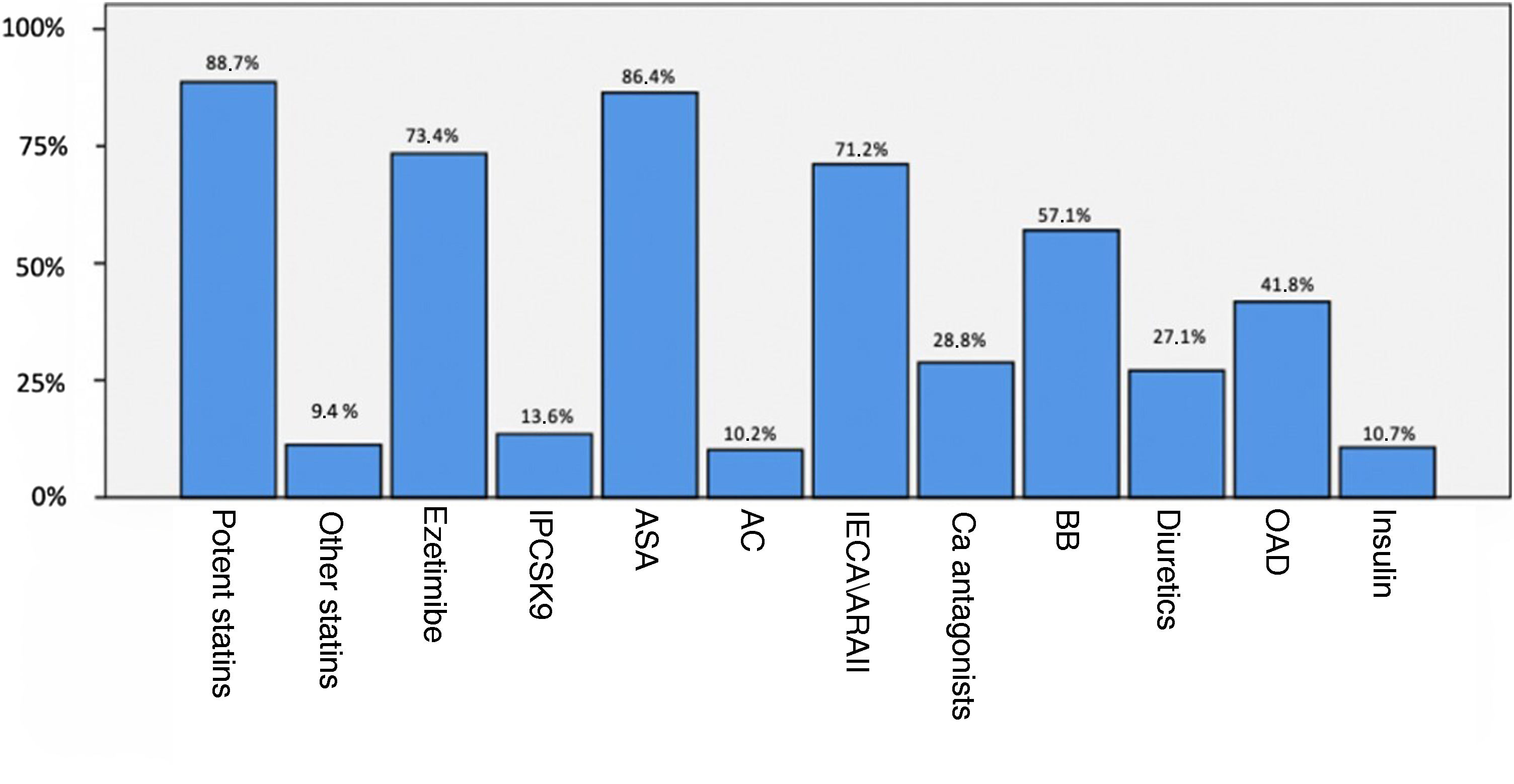

A total of 98.3% of service users were taking lipid-lowering treatment (88.7% of these with high-potency statins). Fig. 2 shows the previous treatment of patients with established CVD.

Treatment of patients with previous CVD.

ASA: antiplatelet drugs; AC: anticoagulants; ACEI/ARBs: angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers; BB: beta-blockers; Ca: calcio; CVD; cardiovascular disease: OAD: oral antidiabetic; PCSK9i: proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 inhibitors.

Of the 177 with clinical CVD, 144 (81.4%) had ischaemic heart disease, 45 (25.4%) had symptomatic peripheral arterial disease, and 11 (6.2%) had cerebrovascular involvement. The total number of events was 190 in 177 patients.

Subjects with clinical and subclinical CVD (177 and 37, respectively) were included in the comparative analysis and their clinical-epidemiological characteristics were compared with those without established CVD, with the data summarised in Table 3.

Comparison of variables studied between patients with clinical or subclinical CVD and those without CVD.

| CVD (n = 214) | No CVD (n = 102) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 63.8 ± 11.1 | 50.5 ± 17.5 | P < .01 |

| Sex (% males) | 63% | 41% | P < .001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28 ± 4.5 | 27.1 ± 5.9 | NS |

| Abdominal circumference (cm) | 100 ± 13 | 99 ± 14 | NS |

| HT | 60.3% | 22.5% | P < .001 |

| DM | 34.1% | 23.5% | P = .057 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 95% | 83% | P < .01 |

| Never smoked | 29.4% | 60.8% | P < .001 |

| Never had an alcohol habit | 84% | 92.2% | P = .047 |

| Hepatic steatosis | 17.8% | 14.7% | NS |

| FH of CVD | 27.6% | 28.4% | NS |

| Total cholesterol total (mg/dL) | 147 ± 43 | 181 ± 43 | P < .001 |

| LDL-C (mg/dL) | 72 ± 35 | 101 ± 38 | P < .001 |

| HDL-C (mg/dL) | 50 ± 15 | 69 ± 21 | P < .001 |

| Non-cholesterol (mg/dL) | 97 ± 36 | 123 ± 40 | P < .001 |

| TG (mg/dL) | 130 ± 59 | 119 ± 65 | P = .14 |

| Apo A (mg/dL) | 136 ± 92 | 145 ± 33 | P = .1 |

| Apo B (mg/dL) | 77 ± 25 | 70 ± 21 | P = .006 |

| Lp(a) (nmol/L) | 258 ± 127 | 264 ± 132 | NS |

| HDL/TG | 2.9 ± 1.9 | 2.3 ± 1.7 | P = .006 |

| Glycosylated haemoglobin (%) | 6.2 ± 1.1 | 5.8 ± .8 | P = .002 |

| HOMA | 3.5 ± 2.8 | 4.2 ± 5.1 | NS |

| Uric acid (mg/dL) | 5.3 ± 1.8 | 4.7 ± 1.3 | P = .01 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | .95 ± .32 | .82 ± .2 | P < .001 |

Apo A: apolipoprotein A; apo B: apolipoprotein B; BMI: body mass index; CVD: cardiovascular disease; DM: diabetes mellitus; FH: family history; HDL: high-density lipoprotein; HDL-C: high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HDL/TG: high-density lipoprotein to triglycerides ratio; HOMA: insulin resistance index; HT: hypertension; LDL-C: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; Lp(a): lipoprotein(a); NS: no statistical significance; TG: triglycerides.

Values expressed as mean ± SD and percentages.

We have exhaustively described our patients with elevated Lp(a) to determine their clinical characteristics, CVRF control, and to identify different phenotypes and user profiles.

In our population, the subjects had an average age of around 60 years, with a notable presence of previous CVRFs (almost 50% HT, 56% carbohydrate metabolism disorders, and 92% dyslipidaemia), significant smoking and anthropometric characteristics typical of metabolic syndrome (mainly overweight and increased abdominal circumference). The prevalence of clinical or subclinical CVD is 68%, much higher than in the general population,14,15 and the high percentage of early onset CVD is noteworthy. Our population is very similar to that of the SANTORINI study, although somewhat younger and with a lower percentage of CVD than this prospective observational study describing the use of lipid-lowering therapies in patients aged ≥18 years with high CVR between 2020 and 2021 in primary and secondary care in 14 European countries.16 When analysing our results, we must bear in mind that we are dealing with a selected population (tests ordered in the hospital setting), which makes it difficult to extrapolate these findings to the general population. Primary care should be encouraged to request this parameter in the lipid profile, in order to better stratify CVR.

The high prevalence of ischaemic heart disease with respect to the incidence of cerebrovascular involvement in our sample is striking, which could be in line with the apparent lesser association of Lp(a) with cerebrovascular events in relation to involvement in other areas.2,17 However, there seems to be a clear selection bias in our model, since cardiologists request much more Lp(a) analysis than neurologists and vascular surgeons refer almost all their patients to us, and it is us in our CVR unit who usually request it.

From our research study, worth mentioning, due to its potential relevance, is the age of onset of CVD compared with other studies such as that of Jortveit et al.,18 where they report an incidence of MI of 4.4% in those under 45 years of age and 27% in those under 60 years of age, with an incidence of clinical CVD of 15.8% and 47.3% in our sample for these age groups with baseline characteristics very similar to ours, but without knowing the Lp(a) values in the aforementioned study.

Therefore, early measurement of Lp(a) should be considered in global health estimates, since its values are genetically determined19 and, therefore, are elevated from a young age.20 This represents a significant increase in CVR that is often not known, but which influences the early onset of CVD.

Subjects with cardiovascular disease vs. subjects without cardiovascular diseaseAs shown in Table 3, there is a higher prevalence of CVRFs in patients with CVD. A higher proportion of males, predominance of HT, dyslipidaemia, and altered carbohydrate metabolism parameters (higher rate of DM 34.1 vs. 23.5%, P = .057), although without reaching statistical significance in probable relationship to the sample size in some of them.

No differences were found in Lp(a) levels between groups; they were elevated in both due to the study design, although in stratifying Lp(a)-associated risk we prefer to refer to thresholds rather than a linear association.21 It is noteworthy that patients without CVD were younger (14 years younger on average) and given that CVD is strongly associated with age, LDL cholesterol (LDL-C) levels and other CVRFs altered over time rather than at a point in time, it is possible that they are more likely to develop CVD in the future than those with normal Lp(a) levels. This assumption supports the theory that it would be advisable to test Lp(a) values early to stratify the CVR of our service users and perform early interventions if necessary.

Lipid profile parameters that can be controlled by medication (total cholesterol, LDL, and non-HDL) were lower in the subjects with CVD, however, other atherogenic factors such as HDL, TG, and HDL/TG ratio were worse in these subjects, suggesting that their treatment was better adjusted to their CVR, as far as possible, while maintaining residual untreatable risk. If we further compare with data from the SANTORINI study,14 our subjects were more appropriately treated as only 8.5% had no lipid-lowering therapy (21.8% in SANTORINI). And in those with previous CVD, the difference increases to 21.2% with no lipid lowering method in SANTORINI vs. 1.7% in our patients. Knowing the Lp(a) value also probably played a role in better adjusted treatment at the cardiovascular level. Furthermore, with regard to the lipid profile objectives in service users with established CVD,11 in our sample 35.3% were found to have LDL < 55 mg/dL vs. 20.7% of the subjects in the SANTORINI study, highlighting that several of our participants were collected at the time of the cardiovascular event, therefore more follow-up time is needed to appreciate the effect of the lipid-lowering therapy started at that time.

Despite being a retrospective observational study, the main strength of our study is its large sample size. However, its main limitation may be a selection bias due to patients with an already high previous CVR. However, a prospective follow-up of subjects without CVD could be considered to assess whether the age of onset of CVD in these subjects is lower than in those with normal Lp(a) levels and high previous CVR.

ConclusionsOur Lp(a) patients are a very high CVR group and may constitute a subgroup of early CVD risk. Lp(a) in our setting is only measured in the specialist care setting and, generally, in the context of secondary prevention, but it would be reasonable to consider identifying this risk factor early (before the onset of CVD) and incorporating it into routine clinical practice, so as to be able to perform interventions in primary prevention and improve control of other CVRFs.

FundingNo funding was received for conducting this study.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.