The usefulness of the lab analysis considered routine testing for the identification of abnormalities in the surgical care has been questioned.

ObjectiveTo determine the percentage of unnecessary laboratory tests in the preoperative assessment as well as to estimate the unnecessary expenses.

Materials and methodsA descriptive, cross-sectional study of patients referred for surgical evaluation between January 1st and March 31st 2013. The database of laboratory testing and electronic files were reviewed. Reference criteria from surgical services were compared with the tests requested by the family doctor.

ResultsIn 65% of the patients (n=175) unnecessary examinations were requested, 25% (n=68) were not requested the tests that they required, and only 10% of the patients were requested laboratory tests in accordance with the reference criteria (n=27). The estimated cost in unnecessary examinations was $1,129,552 in a year.

DiscussionThe results were similar to others related to this theme, however, they had not been revised from the perspective of the first level of attention regarding the importance of adherence to the reference criteria which could prevent major expenditures.

ConclusionIt is a priority for leaders and operational consultants in medical units to establish strategies and lines of action that ensure compliance with institutional policies so as to contain spending on comprehensive services, and which in turn can improve the medical care.

Se ha cuestionado la utilidad de los exámenes de laboratorio considerados de rutina para la identificación de anormalidades en la atención quirúrgica.

ObjetivoDeterminar el porcentaje de exámenes de laboratorio innecesarios en la valoración preoperatoria, así como estimar el gasto innecesario.

Material y métodosEstudio transversal, descriptivo de pacientes para valoración quirúrgica, del 1 de enero al 31 de marzo de 2013. Se revisó la base de datos de laboratorio y el expediente electrónico. Se compararon los criterios de referencia de los servicios quirúrgicos con los exámenes solicitados por el médico familiar.

ResultadosEn el 65% de los pacientes (n=175) se solicitó exámenes innecesarios, al 25% (n=68) no se les solicitó los exámenes que requerían, y únicamente al 10% de los pacientes se les solicitó los exámenes de laboratorio de acuerdo con los criterios de referencia (n=27). El gasto estimado en un año fue de $1,129,552 en exámenes innecesarios.

DiscusiónLos resultados fueron similares a otros relacionados con el tema, sin embargo, no se había revisado desde la perspectiva del primer nivel de atención la importancia que tiene el apego a los criterios de referencia, lo que podría evitar mayores gastos.

ConclusionesResulta prioritario que las áreas directivas y de asesoría operativa en las unidades médicas de primer nivel de atención médica establezcan estrategias y líneas de acción que aseguren el cumplimiento de políticas institucionales para la contención del gasto en servicios integrales y que, a su vez, mejoren la atención médica.

During healthcare, one method of studying disease in any of its stages is through physical examination and a full medical history. This study is complemented with laboratory tests, to identify abnormalities which may put the patient at risk, provide an initial parameter of the patient's general state of health so that any major post-operative changes may be monitored and to identify major asymptomatic conditions.1–3 Laboratory tests considered routine for surgical assessment vary depending on the type of surgery, the patient's own condition and the patient's history of chronic or severe disease.3 The following tests are generally considered to be routine: complete haematic biometry, blood chemistry, serum electrolytes and a general urine test, as a reference of the patient's metabolic or infectious state of health.

It has been proven that the request for these tests is of little practical assistance to patients who require non cardiovascular surgery for prediction of complications, especially clinically healthy patients under 40.3–5 As a result, healthcare costs increase due to too many routine para clinical tests, which are unnecessary, and it has been estimated that between $2,811,097 and $3,345,2062 Mexican pesos have been spent. In United States annual costs for these services have been estimated at $3,000,000,000 dollars.4

In patients who require outpatient surgical procedures, both endoscopic and open surgery type, 30.6% of tests are abnormal, but in only 1.3% are they so clinically important as to suspend surgery and in those patients who were not requested to have or who do not have routine laboratory tests, a high percentage do not present with post-operative complications.5

The abnormal laboratory test results are more frequent in age groups of 41–60 and those over 60, with no statistically significant differences in the frequency of complications or death among those patients’ with abnormal results (in haematic biometry, glycaemia, electrolytes, coagulation and general urine tests) and those patients with normal test results. Only abnormal test results in ureic nitrogen/creatinine test are related to cardiac complications after surgery and a longer hospital stay period.3 The factors associated with complications in surgery are: being over 40, type of surgery and level of invasion of surgical procedure, together with individual history of diseases found in the clinical history of the patient.6

The aim of our study was to identify the proportion of unnecessary laboratory studies, due to the lack of application of reference criteria to the second level of medical care for surgical assessment, frequency of requests due to study type and annual estimation of unnecessary expenditure.

Materials and methodsA descriptive, cross-sectional study was conducted revising the reference criteria of secondary level healthcare surgical services, by the Family Medicine Unit No. 66, in coordination with the Hospital General de Zona No. 11 to optimise the use of global healthcare services. A collegiate group was formed for the creation of these reference criteria, with participation from primary level healthcare doctors, responsible for identifying the patients who required some type of specialised care, and secondary level care surgeons, who were in charge of surgical procedure protocols.

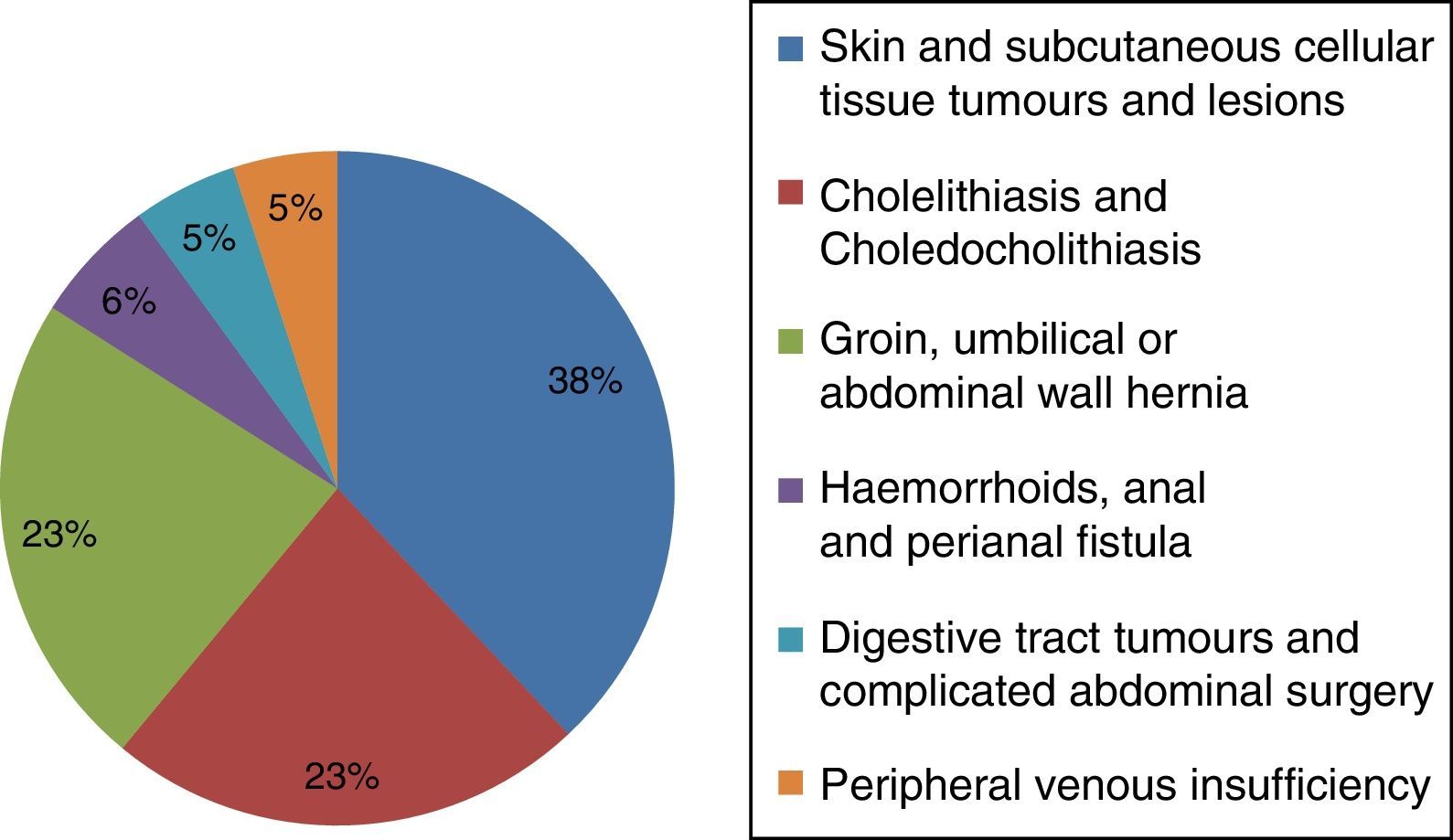

The medical histories of patients of both genders and any age who required non cardiovascular surgical assessment in the Family Medicine Unit No. 66 were reviewed, during the first quarter of 2013. There were 6 main grounds for referral to a secondary medical care level, which were: (1) skin and subcutaneous cellular lesions, (2) cholelithiasis and choledocholithiasis, (3) groin, umbilical or abdominal wall hernia, (4) haemorrhoids, anal and perianal fistula, (5) digestive tract tumours and abdominal surgery, and (6) peripheral venous insufficiency. Incomplete medical files were excluded, as were those patients who did not have a scheduled assessment appointment during the period of study.

Proportions were obtained for the qualitative and average variables, as well as standard deviation in quantitative variables from the Epi-Data 3.1 statistical pack of the Pan American Health Organisation.

Test findings were reviewed using the WINLAB programme, which is a specialised programme from the Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social, for recording laboratory tests by patient and study dates, identifying patients from their social security number and their name.

Matching was applied to verify compliance of reference criteria in accordance with: the service of referral, type of disease, patient's age and the presence of a history of disease.

Since the laboratory testing was of no real cost in the institute, an average was estimated of the cost of each test from 3 private laboratories.

The protocol was assessed and approved by the Local Ethics and Ethics in Research Committee recorded under number R-2014-3004-38.

ResultsOut of the 700 patients referred for surgery during the first quarter of 2013, 268 of them who met with the inclusion criteria were reviewed (38.28%). 59.33% were female (n=159) and 40.67% were male (n=109). The average age was 45 with a range from 5 to 91 years of age and a standard deviation of 5 years.

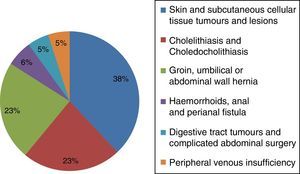

Of the 6 groups of diagnostic referrals for secondary medical care, the group with the highest frequencies were those with skin and subcutaneous cellular tissue lesions and tumours at 38%, followed by cholelithiasis and choledocholithiasis at 23%, groin, umbilical or abdominal wall hernia at 23%, haemorrhoids, anal and perinal fistula at 6%, digestive tract tumours and complicated abdominal surgery at 5% and peripherical venous insufficiency at 5% (Fig. 1).

Regarding the laboratory tests, 65% of patients were identified (n=175) as having been requested unnecessary tests, with a minimum of one and up to 8 unnecessary tests, 25% of patients (n=66) were not offered the tests they required according to the reference criteria and only 10% of patients were requested laboratory tests in keeping with the reference criteria (n=27).

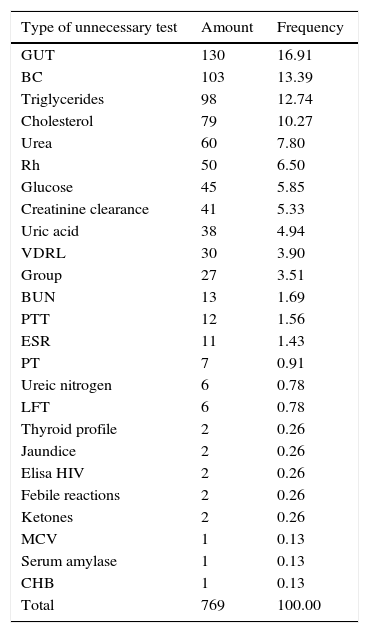

25 different types of exams were requested which included 769 unnecessary laboratory tests. Table 1 lists the simple frequencies, by test type.

Simple frequency according to unnecessary tests.

| Type of unnecessary test | Amount | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| GUT | 130 | 16.91 |

| BC | 103 | 13.39 |

| Triglycerides | 98 | 12.74 |

| Cholesterol | 79 | 10.27 |

| Urea | 60 | 7.80 |

| Rh | 50 | 6.50 |

| Glucose | 45 | 5.85 |

| Creatinine clearance | 41 | 5.33 |

| Uric acid | 38 | 4.94 |

| VDRL | 30 | 3.90 |

| Group | 27 | 3.51 |

| BUN | 13 | 1.69 |

| PTT | 12 | 1.56 |

| ESR | 11 | 1.43 |

| PT | 7 | 0.91 |

| Ureic nitrogen | 6 | 0.78 |

| LFT | 6 | 0.78 |

| Thyroid profile | 2 | 0.26 |

| Jaundice | 2 | 0.26 |

| Elisa HIV | 2 | 0.26 |

| Febile reactions | 2 | 0.26 |

| Ketones | 2 | 0.26 |

| MCV | 1 | 0.13 |

| Serum amylase | 1 | 0.13 |

| CHB | 1 | 0.13 |

| Total | 769 | 100.00 |

CHB: complete haematic biometry; BUN: blood urea nitrogen; GUT: general urine testing; LFT: liver function tests; BC: blood chemistry; Rh: rhesus protein of red blood cell membrane; PT: prothrobin time; PTT: partial thromboplastin time; VDRL: venereal disease research laboratory, serological testing to detect infection by syphilis; MCV: mean corpuscular volume; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; ESR: erythrocyte sedimentation rate.

In the morning shift 57% of the laboratory tests were unnecessary (n=101), 57.3% of patients were not requested to have tests even when they were required for surgical evaluation (n=39) and only 33.3% of patients in this shift met with the reference criteria for surgical evaluation (n=9).

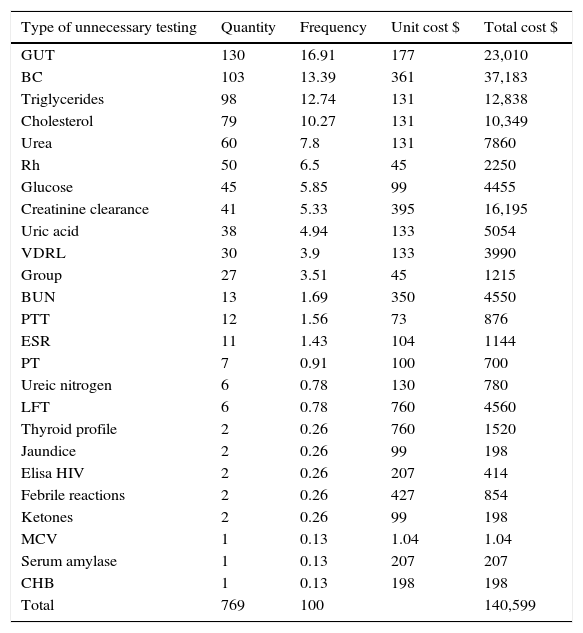

A cost of approximately $140,599 pesos was derived from unnecessary laboratory tests in the study sample (Table 2). These tests were only taken from patients who met with the selection criteria in the quarter (n=268).

Simple frequency according to type of unnecessary laboratory testing and costs.

| Type of unnecessary testing | Quantity | Frequency | Unit cost $ | Total cost $ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GUT | 130 | 16.91 | 177 | 23,010 |

| BC | 103 | 13.39 | 361 | 37,183 |

| Triglycerides | 98 | 12.74 | 131 | 12,838 |

| Cholesterol | 79 | 10.27 | 131 | 10,349 |

| Urea | 60 | 7.8 | 131 | 7860 |

| Rh | 50 | 6.5 | 45 | 2250 |

| Glucose | 45 | 5.85 | 99 | 4455 |

| Creatinine clearance | 41 | 5.33 | 395 | 16,195 |

| Uric acid | 38 | 4.94 | 133 | 5054 |

| VDRL | 30 | 3.9 | 133 | 3990 |

| Group | 27 | 3.51 | 45 | 1215 |

| BUN | 13 | 1.69 | 350 | 4550 |

| PTT | 12 | 1.56 | 73 | 876 |

| ESR | 11 | 1.43 | 104 | 1144 |

| PT | 7 | 0.91 | 100 | 700 |

| Ureic nitrogen | 6 | 0.78 | 130 | 780 |

| LFT | 6 | 0.78 | 760 | 4560 |

| Thyroid profile | 2 | 0.26 | 760 | 1520 |

| Jaundice | 2 | 0.26 | 99 | 198 |

| Elisa HIV | 2 | 0.26 | 207 | 414 |

| Febrile reactions | 2 | 0.26 | 427 | 854 |

| Ketones | 2 | 0.26 | 99 | 198 |

| MCV | 1 | 0.13 | 1.04 | 1.04 |

| Serum amylase | 1 | 0.13 | 207 | 207 |

| CHB | 1 | 0.13 | 198 | 198 |

| Total | 769 | 100 | 140,599 |

CHB: complete haematic biometry; BUN: blood urea nitrogen; GUT: general urine testing; LFT: liver function tests; BC: blood chemistry; Rh: rhesus protein of red blood cell membrane; PT: prothrobin time; PTT: partial thromboplastin time; VDRL: venereal disease research laboratory, serological testing to detect infection by syphilis; MCV: mean corpuscular volume; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; ESR: erythrocyte sedimentation rate.

Every year the overall service costs of the Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social increase considerably. These include routine laboratory tests. This is mainly due to the increase in the number of subscribers and to a higher use of medical services by subscribers who previously did not use them. As a result, reference criteria (Table 3) were established for secondary medical care, one part of which comprises the minimum laboratory tests established for appropriate assessment for any type of surgery, by age and by each individual patient's condition.7,8 These are used by both primary and secondary care doctors, particularly when there is uncertainty about any unidentified clinical complication.6,7

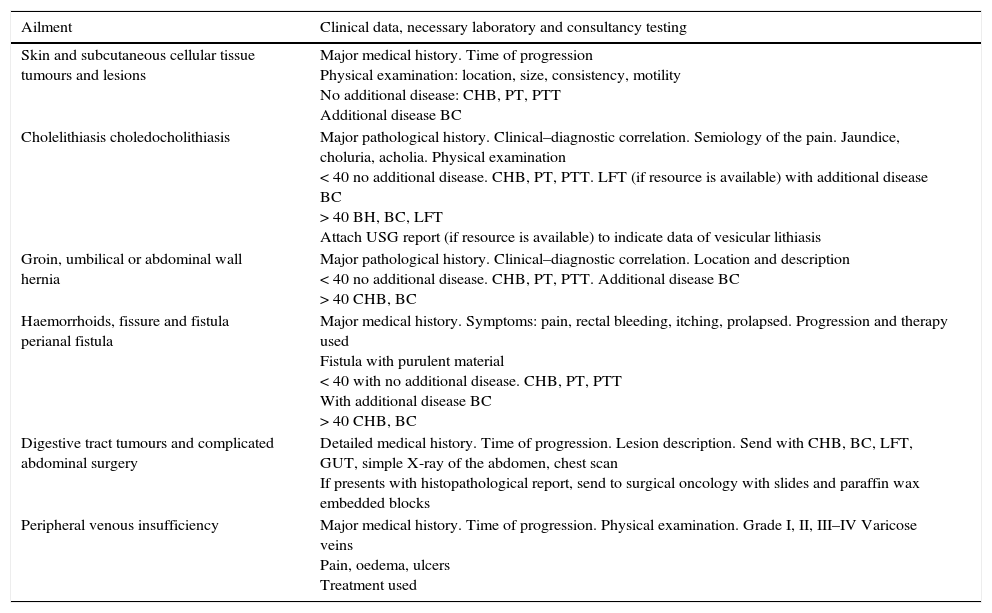

Healthcare criteria and referral for surgery.

| Ailment | Clinical data, necessary laboratory and consultancy testing |

|---|---|

| Skin and subcutaneous cellular tissue tumours and lesions | Major medical history. Time of progression Physical examination: location, size, consistency, motility No additional disease: CHB, PT, PTT Additional disease BC |

| Cholelithiasis choledocholithiasis | Major pathological history. Clinical–diagnostic correlation. Semiology of the pain. Jaundice, choluria, acholia. Physical examination < 40 no additional disease. CHB, PT, PTT. LFT (if resource is available) with additional disease BC > 40 BH, BC, LFT Attach USG report (if resource is available) to indicate data of vesicular lithiasis |

| Groin, umbilical or abdominal wall hernia | Major pathological history. Clinical–diagnostic correlation. Location and description < 40 no additional disease. CHB, PT, PTT. Additional disease BC > 40 CHB, BC |

| Haemorrhoids, fissure and fistula perianal fistula | Major medical history. Symptoms: pain, rectal bleeding, itching, prolapsed. Progression and therapy used Fistula with purulent material < 40 with no additional disease. CHB, PT, PTT With additional disease BC > 40 CHB, BC |

| Digestive tract tumours and complicated abdominal surgery | Detailed medical history. Time of progression. Lesion description. Send with CHB, BC, LFT, GUT, simple X-ray of the abdomen, chest scan If presents with histopathological report, send to surgical oncology with slides and paraffin wax embedded blocks |

| Peripheral venous insufficiency | Major medical history. Time of progression. Physical examination. Grade I, II, III–IV Varicose veins Pain, oedema, ulcers Treatment used |

CHB: complete haematic biometry; GUT: general urine test; LFT: liver function tests; BC: blood chemistry; XR: X-ray; PT: prothrombin time; PTT: partial thromboplastin time.

However, a major finding in this study is that only 25% of the laboratory rests are mentioned in the primary level medical file or in the note which is sent to surgery. It has been reported that criteria must be established for the optimisation of laboratory resources, and their application which would entail limiting predictive use of routine tests and a rational use of the clinical laboratory service in units to avoid unnecessary expense whilst simultaneously reducing medical attention time.9–11

In our study we identified that, despite the necessary tests being specified by surgery type in the reference criteria, these criteria would not be taken into account when the laboratory tests were requested.

It is of note that 53% of the unnecessary tests consist of general urine, blood chemistry, cholesterol and triglyceride tests. There is no justification for requesting such tests when we take into consideration that the main grounds for assessment is skin and subcutaneous cellular tissue lesions and tumours.

It has been estimated that the overall costs of unnecessary tests is $140,599 in the study sample. If we consider that the complete quarter would be $282,388, and on the assumption that the tests would be requested in a uniform manner throughout the year, the expenditure projection for the whole year would amount to $1,129,552.00. These unnecessary laboratory tests for patients referred for surgery leads to escalating health care costs.2,4

ConclusionsPrioritisation in management areas and operational consultancy in primary healthcare units should be given to the establishment of lines of action to ensure compliance with institutional policies to contain the cost of global services. The effect of this would be to improve medical attention, with the obligatory interpretation of laboratory testing. Care could then be offered in keeping with each particular case and could involve the request for the minimum necessary tests, depending on the type of surgery involved. Similarly, cases where it has been scientifically proven that preoperative testing is unnecessary should be defined.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Our thanks go to Doctor Graciela Mota Velazco, ex director of the Unidad de Medicina Familiar No. 66, and the chemist Mario Ortiz, head of the department of the Clinical Laboratory of the UMF 66, for their interest in improving the clinic's services.

Please cite this article as: Mata-Miranda MP, Cano-Matus N, Rodriguez-Murrieta M, Guarneros-Zapata I, Ortiz M. Exámenes de laboratorio de rutina innecesarios en pacientes referidos para atención por servicios quirúrgicos. Cirugía y Cirujanos. 2016;84:119–124.