Patients with placenta accreta have a high frequency of complications and death risk.

ObjectiveThe aim of this study was to compare the results of scheduled hysterectomy vs. urgent hysterectomy in patients with placenta accreta in a high specialty medical unit.

Material and methodsAn observational, comparative, cross-sectional study was conducted by reviewing patient records with confirmed diagnostic of placenta accreta, who attended in a one year period. They were divided into 2 groups based on the type of surgery, scheduled or urgent. Descriptive statistics were applied, with comparisons using Student t-test and chi squared tests. A value of P<0.05 was considered significant.

ResultsThere were 4592 births in the period of study, and 125 obstetric hysterectomies were performed, with 40 confirmed cases of accreta (8.7 per thousand births) with 20 in scheduled and 20 in urgent surgeries, with the most frequent type being placenta accreta. The mean maternal age was 32 years, with a mean of 5h operating time, total bleeding 3135ml, and 3.5 units of packed cells transfused. There was no statistical difference when comparing these variables with re-interventions, hypovolaemic shock, and intensive care unit admission. Caesarean-hysterectomy with hypogastric artery ligation was the most frequent surgery performed.

ConclusionsIn this hospital, scheduled and urgent surgical treatment of patients with placenta accreta show similar results, probably because the constant availability of resources and the experience obtained by the multidisciplinary team in all shifts. Nevertheless, make absolutely sure to perform elective surgery while having all the necessary resources.

Las pacientes con placenta acreta tienen alta frecuencia de complicaciones y riesgo de muerte.

El objetivoDe este estudio fue comparar los resultados de la histerectomía programada vs. histerectomía de urgencia en pacientes con placenta acreta, en una unidad médica de alta especialidad.

Material y métodosEstudio observacional, comparativo, transversal. Se revisaron expedientes de pacientes con diagnóstico confirmado de placenta acreta atendidas en un periodo de un año. Se formaron 2 grupos en base al tipo de cirugía, programada o urgencia. Se aplicó estadística descriptiva, comparaciones mediante t de Student y χ2. Se consideró significativo el valor p≤0.05.

ResultadosEn el periodo de estudio ocurrieron 4592 nacimientos, se realizaron 125 histerectomías obstétricas. Confirmados 40 casos de acretismo (8.7 por mil nacimientos), 20 cirugías programadas y 20 de urgencia, la variedad más frecuente fue placenta acreta. La media de edad materna fue 32 años, el tiempo quirúrgico fue de 5 horas, con un sangrado total de 3135ml y una transfusión de concentrados eritrocitarios de 3.5 unidades. No hubo diferencia estadística al comparar estas variables ni tampoco en reintervenciones, choque hipovolémico, ingresos a unidad de cuidados intensivos y complicaciones. La cirugía que predomino en ambos grupos fue la cesárea – histerectomía con ligadura de arterias hipogástricas.

ConclusionesEn este hospital el tratamiento quirúrgico programado y urgente de pacientes con acretismo placentario muestra resultados similares, probablemente debido a la disponibilidad continua de recursos y a la experiencia que ha adquirido el equipo multidisciplinario en todos turnos. Pese a ello siempre debe procurarse realizar la cirugía programada disponiendo de todos los recursos necesarios.

Placenta accreta occurs when all or part of the placenta abnormally adheres to the myometrium. The incidence has increased from 0.8 to 3 per 1000 pregnancies; the main risk factors are uterine surgeries, placenta praevia and multiparity.1,2

Three categories of abnormal placenta adherence are recognised, which are defined according to the depth of the invasion. The placenta accreta presents in 81.6% of the cases, the increta in 11.8% and percreta up to 6.6%.3 The diagnosis can be performed by ecography with 97% sensitivity and 92% specificity. Magnetic resonance is useful in case ultrasound is not conclusive or there is a high possibility of invasion of other organs or parametria.4,5

Due to the abnormal adherence, this entity is associated with incapacity for the placental extraction and severe haemorrhaging at delivery, frequently requiring the need to perform a hysterectomy to control the haemorrhaging and provision of component therapy in most cases.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists recommends that if there is suspicion of placenta accreta, measures should be taken to optimise the birth and treatment in order to diminish the risk of maternal morbidity and mortality.6 The placenta accreta has not been associated with an increase in foetal morbidity and mortality or intrauterine growth restriction; therefore, foetal monitoring is not modified.7

Patients suspected of placenta accreta should be treated in an institution with the necessary infrastructure for their care.5,6 This should include preoperative assessment by Anaesthesiology and notification of the Blood Bank, as well as to other surgical services such as Oncological Gynaecology, Urology, General Surgery and/or Vascular Surgery.5,8 It is necessary to previously have large venous accesses to allow the entrance of large amounts of liquids, as well as to take prevention measures for thromboembolism and hypothermia.5,8 The need for component therapy is difficult to predict; however, taking into account that patients subjected to caesarean-hysterectomy have a blood loss of around 3000–5000ml, it is necessary to have enough preoperative amounts of blood fractions.9,10

The surgical techniques described are caesarean-hysterectomy; caesarean with section of umbilical cord leaving the placenta in situ and, later, hysterectomy; and, in patients with persistent bleeding, the surgical options include hypogastric artery ligation11 and pelvic packing, which is usually performed in patients with persistent and diffuse bleeding instead of arterial and impossible to inhibit through surgery. The packing is a temporary treatment performed for the purpose of achieving haemodynamic stability and coagulopathy correction.5,10

The risk of postoperative morbidity in patients with placenta accreta surgery is high and includes: hypotension, shock, persistent coagulopathy, anaemia, prolonged surgeries, lesion to organs and even death.5 Kidney, heart and other organs failure, fluid and electrolyte imbalance and compartment syndrome are usually present.5,12

The integrated treatment of these patients with a multidisciplinary team has been carried out in different institutions worldwide with proposals of diagnosis, prenatal monitoring and different managements with the aim of improving the obstetric results and reducing the morbidity and mortality. Eller et al.13 in 2010 compared maternal morbidity in cases of placenta accreta treated by a care team formed by specialists in foetal medicine, experts in obstetric surgery, gynaecologists-oncologists, interventional radiologists, available intensive care unit and a third-level blood bank with reserve volumes for massive transfusion, led by a care norm versus patients treated in conventionally-managed hospitals. They concluded that maternal morbidity is reduced in 50% in women with placenta accreta who finish their pregnancies at a third-level care centre with a multidisciplinary team management.13

Different publications have referred to the importance and benefits for patients of a scheduled surgery with all the human resources and necessary materials available for these cases.10,13,14

The Unidad Médica de Alta Especialidad of the Ginecología y Obstetricia Hospital Num. 3 of the Centro Médico La Raza, is a reference hospital centre with an average of 5000 births per year. Here patients with high risk pregnancies are treated, including those with a presumptive or confirmed diagnosis of placenta accreta. With the aim of preventing morbidity and mortality of this condition in the Unidad Médica de Alta Especialidad of the Ginecología y Obstetricia Hospital Num. 3 of the Centro Médico La Raza, as in other large hospital centres, scheduled surgery is intended to be performed during the morning shift, assuring beforehand that the necessary human resources and materials for the care of the patients are to hand. However, for various reasons some patients have to undergo urgent surgical treatment, which implies that all the necessary resources may not be available, or at least not available in good time for the care.

The aim of this study was to compare the results of scheduled obstetric hysterectomy vs urgent obstetric hysterectomy in patients with placenta accreta in a high specialism medical unit.

Material and methodsAn observational, retrospective, comparative and cross-sectional study was performed in the Unidad Médica de Alta Especialidad of the Gineco Obstetricia Hospital Num 3, Centro Médico La Raza of the Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social, between 1 July, 2010 and 31 June, 2011.

Records of all the patients who underwent caesarean-hysterectomy or obstetric hysterectomy were reviewed. All the cases of patients with confirmed histopathological diagnosis of placenta accreta were included. They were divided into 2 groups based on the type of surgery. In group 1, the cases of patients with scheduled pregnancy interruption were included according to the hospital protocol. In group 2, the cases of patients who underwent urgent surgical treatment by foetal and/or maternal indication were included. There were registered by age, gestations, days of hospital stay, need of admission to the adult intensive care unit, indication of surgery, surgical re-interventions, used operating time and intra- and postoperative complications.

The demographic data were analysed through descriptive statistics; to compare nominal variables χ2 was applied, and for qualitative variables, Student t-test, with ≤0.05 significance. The data were analysed with the statistical package SPSS® version 20.

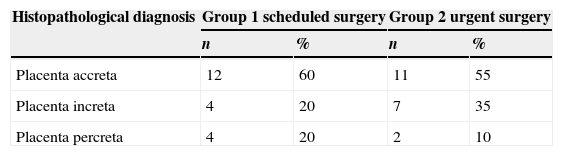

ResultsThere were 4592 births in the period of the study and 125 obstetric hysterectomies were performed for various causes. In the histopathological study of the cases of hysterectomy, the placenta accreta diagnosis was made in 40 (32%) patients, which corresponds to 8.7 cases per 1000 births. Twenty cases correspond to group 1 and the remaining 20 to group 2. According to the invasive degree of the trophoblast in both groups, placenta accreta was the most frequent. The distribution according to the histopathological variety can be observed in Table 1.

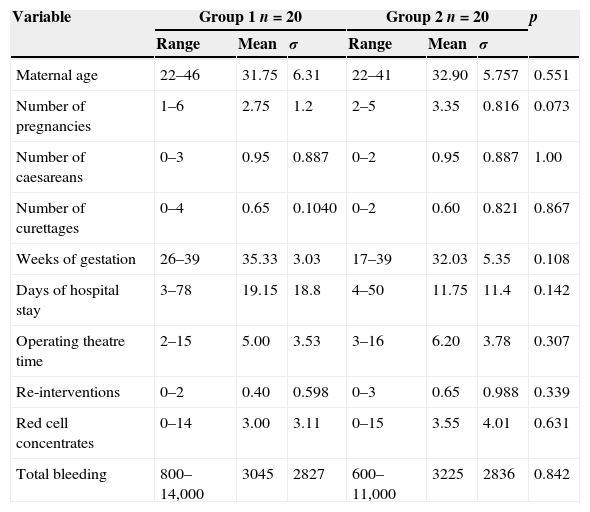

The means for the total of patients were: maternal age 32 years, 5h of operating time, total bleeding 3135ml and 3.5 units of packed cells transfused. The comparison of these variables according to the type of surgery as well as the maternal age and parity can be observed in Table 2.

Comparison of maternal age and obstetric and surgical results of the studied groups.

| Variable | Group 1 n=20 | Group 2 n=20 | p | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | Mean | σ | Range | Mean | σ | ||

| Maternal age | 22–46 | 31.75 | 6.31 | 22–41 | 32.90 | 5.757 | 0.551 |

| Number of pregnancies | 1–6 | 2.75 | 1.2 | 2–5 | 3.35 | 0.816 | 0.073 |

| Number of caesareans | 0–3 | 0.95 | 0.887 | 0–2 | 0.95 | 0.887 | 1.00 |

| Number of curettages | 0–4 | 0.65 | 0.1040 | 0–2 | 0.60 | 0.821 | 0.867 |

| Weeks of gestation | 26–39 | 35.33 | 3.03 | 17–39 | 32.03 | 5.35 | 0.108 |

| Days of hospital stay | 3–78 | 19.15 | 18.8 | 4–50 | 11.75 | 11.4 | 0.142 |

| Operating theatre time | 2–15 | 5.00 | 3.53 | 3–16 | 6.20 | 3.78 | 0.307 |

| Re-interventions | 0–2 | 0.40 | 0.598 | 0–3 | 0.65 | 0.988 | 0.339 |

| Red cell concentrates | 0–14 | 3.00 | 3.11 | 0–15 | 3.55 | 4.01 | 0.631 |

| Total bleeding | 800–14,000 | 3045 | 2827 | 600–11,000 | 3225 | 2836 | 0.842 |

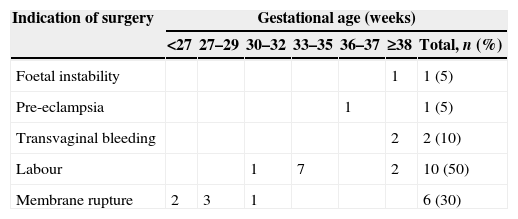

Regarding the gestational age at the time of the birth, all patients from group 1 were scheduled by the placenta praevia and/or accreta diagnosis through ultrasound at 36 weeks of gestational age. It is notable that there were 4 cases of 38-week newborns and one case of 39-week through Capurro assessment. In patients from group 2, 5 cases of newborns with 38 weeks or more of gestational age were registered. The main indications of surgical intervention and gestational age in which the surgery of patients from group 2 was performed are shown in Table 3.

Indication of urgent surgeries and gestational age in which the procedure was performed.

| Indication of surgery | Gestational age (weeks) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <27 | 27–29 | 30–32 | 33–35 | 36–37 | ≥38 | Total, n (%) | |

| Foetal instability | 1 | 1 (5) | |||||

| Pre-eclampsia | 1 | 1 (5) | |||||

| Transvaginal bleeding | 2 | 2 (10) | |||||

| Labour | 1 | 7 | 2 | 10 (50) | |||

| Membrane rupture | 2 | 3 | 1 | 6 (30) | |||

According to the hypovolaemic shock classification in 4 classes (I–IV) depending on the amount of bleeding and its clinical repercussion, 15 (75%) patients from group 1 and 14 (70%) from group 2 showed hypovolaemic shock class III and IV for a value of p=0.883.

Eight (40%) adults from group 1 were admitted into the intensive care unit, who had presented hypovolaemic shock degree iv. Seven (35%) patients from group 2 were admitted, one with shock degree III and 6 with shock degree IV.

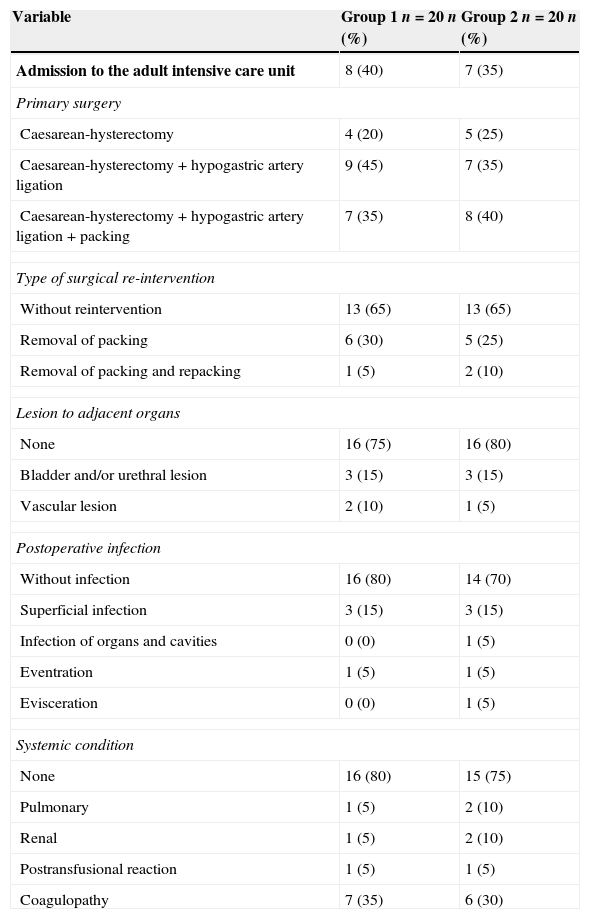

The primary surgeries that were most frequent in the study groups were caesarean-hysterectomy with hypogastric artery ligation (45% in group 1 and 35% in group 2) and caesarean-hysterectomy with hypogastric artery ligation and packing (35% and 40%, respectively).

The coagulopathy manifested by bleeding in layer and haemodynamic instability presented similarly in the 2 groups (35% in group 1 and 30% in group 2). Surgical reintervention was not necessary in 65% of the patients from each group. In those patients who were reintervened, procedures for packing removal were the most frequent.

All patients received surgical treatment with uterus preservation. There was no statistically significant difference through the test χ2 when comparing the type of surgical treatment and postoperative morbidity. Table 4 summarises the procedures performed in the studied cases.

Types of performed surgeries and postoperative morbidity.

| Variable | Group 1 n=20 n (%) | Group 2 n=20 n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Admission to the adult intensive care unit | 8 (40) | 7 (35) |

| Primary surgery | ||

| Caesarean-hysterectomy | 4 (20) | 5 (25) |

| Caesarean-hysterectomy+hypogastric artery ligation | 9 (45) | 7 (35) |

| Caesarean-hysterectomy+hypogastric artery ligation+packing | 7 (35) | 8 (40) |

| Type of surgical re-intervention | ||

| Without reintervention | 13 (65) | 13 (65) |

| Removal of packing | 6 (30) | 5 (25) |

| Removal of packing and repacking | 1 (5) | 2 (10) |

| Lesion to adjacent organs | ||

| None | 16 (75) | 16 (80) |

| Bladder and/or urethral lesion | 3 (15) | 3 (15) |

| Vascular lesion | 2 (10) | 1 (5) |

| Postoperative infection | ||

| Without infection | 16 (80) | 14 (70) |

| Superficial infection | 3 (15) | 3 (15) |

| Infection of organs and cavities | 0 (0) | 1 (5) |

| Eventration | 1 (5) | 1 (5) |

| Evisceration | 0 (0) | 1 (5) |

| Systemic condition | ||

| None | 16 (80) | 15 (75) |

| Pulmonary | 1 (5) | 2 (10) |

| Renal | 1 (5) | 2 (10) |

| Postransfusional reaction | 1 (5) | 1 (5) |

| Coagulopathy | 7 (35) | 6 (30) |

No deaths were registered from the groups of patients during the study period.

DiscussionPlacenta accreta is associated with a considerable morbidity, including coagulopathy, urethral and/or bladder lesion, need for surgical reintervention, infection and systemic disease derived from high loss of blood. The bibliography notes that the incidence has increased from 0.8 to 3 per 1000 pregnancies.1,2 We find an incidence of 8.7 per 1000 births, a number significantly higher than that reported internationally, and we are aware of it because our hospital is a reference centre for patients with high risk pregnancies and for the abuse of caesarean surgery performed in the country in recent years.

Abnormal placenta adherence is defined in the bibliography according to the depth of the invasion, presenting placenta accreta (81.6%), increta (11.8%) and percreta (6.6%).3 In our study, we find placenta accreta in 55.2% of the occasions, increta in 27.5% and percreta in 15%, doubling the percentage of placenta increta and percreta reported in the literature, which increases the transoperative and postoperative morbidity risk. This could explain the average bleeding in our hospital, which is also higher than that reported in other studies.

In this review, 50% of the patients were subjected to urgent surgery and the other 50% to scheduled surgery; other publications report 67% of the elective surgical procedures.15 We should clarify that the high number of urgent procedures is because patients arrive at this hospital spontaneously when presenting transvaginal bleeding, or they are referred from the emergency department of other hospitals.

The gestational age in which the scheduled surgery was performed in patients was ≤36 weeks by ultrasound; however, the assessment of the foetal age at the time of birth by the Capurro scale reported pregnancies up to 39 weeks. Therefore, even though the literature7 indicates that the adherence disorders and placental insertion do not interfere with the foetal growth or increase the risk of foetal morbidity, we find contrary data; consequently, this aspect could be a subject for an additional future study. The urgent termination of pregnancy of 38 or more weeks was because they reached that gestational age and an unreliable amenorrhoea with ultrasonographic report of younger gestational age.

The application of the institutional protocol for diagnosis, monitoring and treatment carried out at the hospital was compiled in 100% of the patients who underwent scheduled surgery, matching the recommendations issued by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists.6

Eller et al.13 in their work published in 2010 note that the patients managed by a multidisciplinary team needed transfusion of less blood than those conventionally managed (43 vs 61%). In this regard, we do not find any difference in our study comparing the volume of transfusion in patients subjected to scheduled surgery vs urgent surgery (p=0.631). Eller et al.13 reported an average blood loss volume of 2000ml in the multidisciplinary care centres and 2500ml in the conventional care centres. In our review, the bleeding media was 3045ml for scheduled surgery and 3225ml for urgent surgery, which could be related to the 40% or more placentas incretas and percretas. The maximum bleeding was 14,000 and 11,000ml in groups 1 and 2, respectively, presenting in patients with histopathological report of placenta percreta with invasion to vascular structures.

In the study published by Eller et al.13 hypogastric artery ligation was carried out during primary intervention in 23 cases (29%) in the multidisciplinary care centres, while it was not performed in any patient of the conventional care centres. In our work, the hypogastric artery ligation was one of the most frequent treatments in the 2 study groups. Several authors argued that procedures such as the hypogastric artery ligation are not as effective and it is a highly difficult technique that does not control the blood supply coming from the collateral branches of the femoral arteries.5,10,13 In our study, this procedure was performed in 31 (77.5%) of the patients. We consider that the surgical experience in the performance of this procedure by the medical personnel of our institution has turned it into the elective and standard treatment in all the shifts.

ConclusionsPlacental adherence disorders are high in our hospital unit and, with tendency to the placenta percreta presentation, associated with higher morbidity.

No statistical difference was found when comparing the surgical treatment and postoperative morbidity; therefore, we conclude that in this hospital, the scheduled surgical treatment of patients with placenta accreta is not different and does not reduce the morbidity compared to the patients who underwent urgent surgery. This can be attributed to the fact that in the hospital the supply of inputs is permanent in all the shifts, and a good degree of maturity and experience was achieved in the medical-surgical treatment of the patients with placenta accreta, globally standardising the surgical technique, resulting in the decrease of maternal morbidity and mortality. Despite this, the scheduled surgery should always be performed with all necessary resources.

Due to the substantial morbidity danger that confronts patients with placenta accreta, it is essential to assess and implement strategies in all hospitals that attend obstetric patients in order to achieve a significant reduction in maternal morbidity and mortality.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Sumano-Ziga E, Veloz-Martínez MG, Vázquez-Rodríguez JG, Becerra-Alcántara G, Jimenez Vieyra CR. Histerectomía programada vs. histerectomía de urgencia en pacientes con placenta acreta, en una unidad médica de alta especialidad. Cir Cir. 2015;83:303–308.