Breast cancer mortality has increased in women 25 years and over, and since 2006 it has surpassed cervical cancer. Breast cancer is a heterogeneous disease, with several clinical and histological presentations that require a thorough study of all clinical and pathological parameters, including immunohistochemistry to classify it into subtypes, have a better prognosis, provide individualised treatment, increase survival, and reduce mortality.

ObjectiveTo evaluate the prevalence of sub-types of breast cancer and the association with the clinical and histopathological features of the tumour.

Material and methodsAn observational, retrospective, cross-sectional and analytical study was conducted on 1380 patients with a diagnosis of breast cancer, and they have been classified by immunohistochemistry into four subtypes: luminal A, triple negative, luminal B and HER2. An analysis was performed on the association with age, risk factors, and the clinical and histopathological features of the tumour.

ResultsThe mean age of the patients was 53.3±11.4 years. The frequency was luminal A (65%), triple negative (14%), luminal B (12%), and HER2 (9%). The most frequent characteristics were in the 50–59 age range, late menopause, the right side, upper external quadrant, stage II, metastatic lymph nodes, and mastectomy.

ConclusionThe most frequent sub-type was luminal A, and together with the luminal B they have better prognosis compared with the triple negative and HER2.

El cáncer de mama ha incrementado la mortalidad en mujeres de 25 años y más, superando al cáncer cervicouterino. Es una enfermedad heterogénea, de presentación clínica e histológica variada con diferentes subtipos, por lo que es indispensable el diagnóstico preciso clínico y anatomopatológico (que incluye la inmunohistoquímica); solo así el tratamiento se individualizará y el pronóstico mejorará y se incrementará la sobrevida, con disminución de la mortalidad.

ObjetivoAnalizar la prevalencia de los subtipos del cáncer de mama y su asociación con las características clínicas e histopatológicas del tumor.

Material y métodosEstudio observacional, retrospectivo, transversal y analítico, realizado en 1,380 pacientes con diagnóstico de cáncer de mama que se clasificaron por inmunohistoquímica en 4 subtipos: luminal A, triple negativo, luminal B y HER2. Se analizó la asociación de las características clínicas e histopatológicas del tumor con la edad y los factores de riesgo.

ResultadosLas pacientes tuvieron edades de 53.3±11.4, la frecuencia de los subtipos fue: luminal A (65%), triple negativo (14%), luminal B (12%) y HER2 (9%): las características más frecuentes fueron: el rango de edad de 50 a 59 años, menopausia tardía, mama derecha, cuadrante superoexterno, la etapa II, los ganglios metastásicos y la mastectomía.

ConclusionesEl subtipo más frecuente fue el luminal A, y junto con el luminal B son los que tienen mejor pronóstico en comparación con el triple negativo y HER2.

Breast cancer has become more prevalent in recent decades and is now the most common cancer worldwide. It represents 16% of all types of female cancer, and although it is considered a first-world illness, most deaths are registered in developing countries.1,2 The low survival rates in these countries can mainly be explained by the lack of efficient programmes to detect, diagnose and treat the disease.3 The increase in breast cancer mortality is a public health issue, given that since 2006 it has surpassed cervical cancer.4 Breast cancer is a heterogeneous disease that presents with different clinical and histopathological characteristics at the moment of diagnosis. The prognosis factors are the individual characteristics of the tumour and the patient, and their analysis and assessment are essential to choose the most specific and efficient treatment to increase survival and reduce mortality.5,6 In 2006, Carey et al.7 categorised breast cancer by immunohistochemistry (IHC) in: luminal A (ER+ and/or PR+ and HER2−), luminal B (ER+ and/or PR+ and HER2+), basal-like (ER−, PR−, HER2−, cytokeratin 5/6 positive or HER1+), HER2+/ER− (ER−, PR− and HER2+) and with no categorisation when they tested negative for the five markers (RE, RP, HER2neu, HER1 and cytokeratin 5/6).

This method represents a more feasible alternative since half of breast cancer cases occur in countries where the analysis of prognosis factors must be inexpensive, simple and easy to replicate. Luminal A and B subtypes are the ones with the best prognosis and respond to hormone therapy; HER2 and triple negative have the worst prognosis and are only responsive to chemotherapy.8,9 Several studies concur that luminal A subtype is the most common one.10–12 The current histological categorisation of breast carcinomas does not reflect the heterogeneity of tumours in their biological behaviour, nor does it allow identifying the patients who will have a better response or who will benefit from the different therapies. The clinical and prognostic diversity of breast carcinomas are similar and homogeneous regarding their classic prognosis factors, but express different genes at a molecular level that ascribe them biological and prognostic variability; studying these genes has enabled us to understand the biological behaviour of breast cancer and to personalise prognosis and treatment for patients.13–15 Several studies suggest that with a limited amount of immunohistochemistry markers, breast carcinomas can be categorised into subtypes equivalent to those based on gene expression profiles; the advantage of the immunohistochemistry analysis is that it uses markers that are available at most anatomical pathology services.16–18 This categorisation reveals prognostic differences with statistical importance in the recurrence, survival and mortality of triple negative and HER2 subtypes, compared to luminal A and B subtypes.19–21

The purpose of this study was to analyse the predominance of breast cancer subtypes by immunohistochemistry and to analyse the association between age, risk factors, and clinical and histopathological characteristics of the tumour.

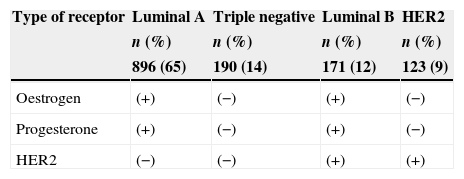

Material and methodsAn observational, retrospective, cross-sectional and analytical study conducted for a period of seven years, from 1 January 2007 to 31 December 2013, at the Hospital General Regional 72 of the Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social, which was a reference hospital for East Mexico, West Mexico and the North Federal District areas for oncology services during that period. The surgical oncology service registered 9.058 first-time consultations, whereas the Hospital General Regional 196 from the same area registered 4787. 1380 patients were included who met the inclusion criteria: having stage I, II and III breast cancer, having being treated with radical curative surgery (quadrantectomy or mastectomy with axillary dissection) and having immunohistochemistry results. Depending on the immunohistochemistry results, they were categorised into four subtypes: luminal A (RE+, RP+, HER2−), triple negative (RE−, RP−, HER2−), luminal B (RE+, RP+, HER2+) and HER2 (RE−, RP−, HER2+). The association between subtypes and clinical and histopathological variables such as age, risk factors, affected side, quadrant, clinical stage, tumour size, type of surgery and metastatic ganglia was analysed.

The descriptive statistics were calculated for the frequency and percentage variables, and square Chi was calculated to analyse the link between variables and subtypes using the SPSS programme, version 20.

ResultsThere were 1380 patients with breast cancer diagnosis, age range between 30 and 86 years, mean 53.3±11.4, and they were categorised into four subtypes by immunohistochemistry. The frequency was luminal A (65%), triple negative (14%), luminal B (12%) and HER2 (9%) (Table 1).

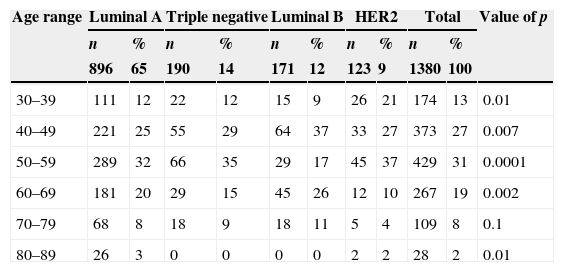

By grouping patients by age, the highest frequency was observed in the age range 50–59 years (31%); by analysing the association between subtypes and age ranges, the highest frequency was found between luminal A and 80–89 years (3%), luminal B with 40–49 years (37%) and with 60–69 years (26%), and HER2 with 30–39 years (21%) and with 50–59 years (37%) with a significant p. The age range between 70 and 79 was not linked to any subtype, nor was there an association between the triple negative subtype to any age range (Table 2).

Frequency of subtypes by age ranges.

| Age range | Luminal A | Triple negative | Luminal B | HER2 | Total | Value of p | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| 896 | 65 | 190 | 14 | 171 | 12 | 123 | 9 | 1380 | 100 | ||

| 30–39 | 111 | 12 | 22 | 12 | 15 | 9 | 26 | 21 | 174 | 13 | 0.01 |

| 40–49 | 221 | 25 | 55 | 29 | 64 | 37 | 33 | 27 | 373 | 27 | 0.007 |

| 50–59 | 289 | 32 | 66 | 35 | 29 | 17 | 45 | 37 | 429 | 31 | 0.0001 |

| 60–69 | 181 | 20 | 29 | 15 | 45 | 26 | 12 | 10 | 267 | 19 | 0.002 |

| 70–79 | 68 | 8 | 18 | 9 | 18 | 11 | 5 | 4 | 109 | 8 | 0.1 |

| 80–89 | 26 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 28 | 2 | 0.01 |

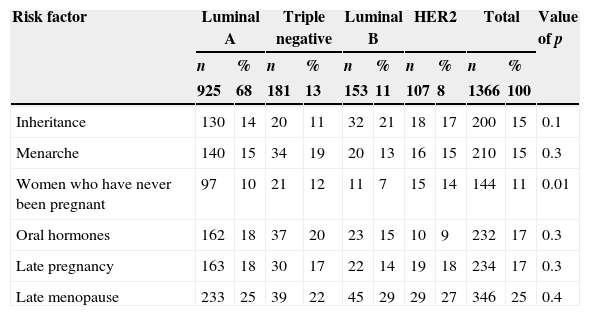

Of the risk factors, the most frequent was late menopause (25%), although in the statistical analysis there was no association with any subtype; there was only an association between HER2 subtype with women who had never been pregnant (14%), with a significant p (Table 3).

Subtypes and risk factors.

| Risk factor | Luminal A | Triple negative | Luminal B | HER2 | Total | Value of p | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| 925 | 68 | 181 | 13 | 153 | 11 | 107 | 8 | 1366 | 100 | ||

| Inheritance | 130 | 14 | 20 | 11 | 32 | 21 | 18 | 17 | 200 | 15 | 0.1 |

| Menarche | 140 | 15 | 34 | 19 | 20 | 13 | 16 | 15 | 210 | 15 | 0.3 |

| Women who have never been pregnant | 97 | 10 | 21 | 12 | 11 | 7 | 15 | 14 | 144 | 11 | 0.01 |

| Oral hormones | 162 | 18 | 37 | 20 | 23 | 15 | 10 | 9 | 232 | 17 | 0.3 |

| Late pregnancy | 163 | 18 | 30 | 17 | 22 | 14 | 19 | 18 | 234 | 17 | 0.3 |

| Late menopause | 233 | 25 | 39 | 22 | 45 | 29 | 29 | 27 | 346 | 25 | 0.4 |

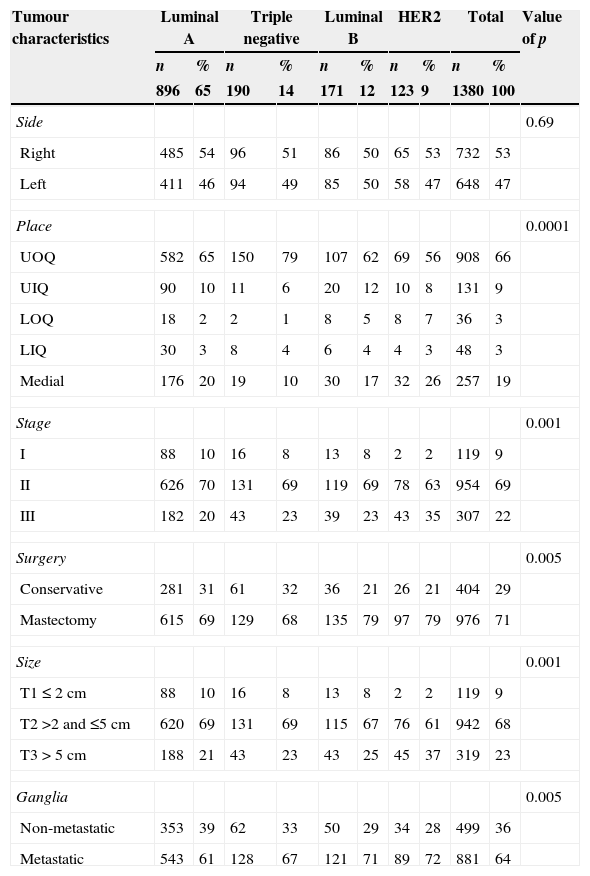

The characteristics of the most common tumour were: right side 53%, upper outer quadrant 66%, stage II 69%, mastectomy 71%, T2 size 68% and metastatic ganglia 64%. Association of subtypes with tumour characteristics was found between luminal A with stage I (10%), stage II (70%), T1 size (10%), T2 size (69%) and non-metastatic ganglia (39%); triple negative with upper outer quadrant (79%) and conservative surgery (32%); luminal B with mastectomy (79%); HER2 with stage III (35%), T3 size (37%), mastectomy (79%) and metastatic ganglia (72%), with a significant p; there was no association between sides and subtypes (Table 4).

Subtypes and tumour characteristics.

| Tumour characteristics | Luminal A | Triple negative | Luminal B | HER2 | Total | Value of p | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| 896 | 65 | 190 | 14 | 171 | 12 | 123 | 9 | 1380 | 100 | ||

| Side | 0.69 | ||||||||||

| Right | 485 | 54 | 96 | 51 | 86 | 50 | 65 | 53 | 732 | 53 | |

| Left | 411 | 46 | 94 | 49 | 85 | 50 | 58 | 47 | 648 | 47 | |

| Place | 0.0001 | ||||||||||

| UOQ | 582 | 65 | 150 | 79 | 107 | 62 | 69 | 56 | 908 | 66 | |

| UIQ | 90 | 10 | 11 | 6 | 20 | 12 | 10 | 8 | 131 | 9 | |

| LOQ | 18 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 8 | 5 | 8 | 7 | 36 | 3 | |

| LIQ | 30 | 3 | 8 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 48 | 3 | |

| Medial | 176 | 20 | 19 | 10 | 30 | 17 | 32 | 26 | 257 | 19 | |

| Stage | 0.001 | ||||||||||

| I | 88 | 10 | 16 | 8 | 13 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 119 | 9 | |

| II | 626 | 70 | 131 | 69 | 119 | 69 | 78 | 63 | 954 | 69 | |

| III | 182 | 20 | 43 | 23 | 39 | 23 | 43 | 35 | 307 | 22 | |

| Surgery | 0.005 | ||||||||||

| Conservative | 281 | 31 | 61 | 32 | 36 | 21 | 26 | 21 | 404 | 29 | |

| Mastectomy | 615 | 69 | 129 | 68 | 135 | 79 | 97 | 79 | 976 | 71 | |

| Size | 0.001 | ||||||||||

| T1≤2cm | 88 | 10 | 16 | 8 | 13 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 119 | 9 | |

| T2 >2 and ≤5cm | 620 | 69 | 131 | 69 | 115 | 67 | 76 | 61 | 942 | 68 | |

| T3>5cm | 188 | 21 | 43 | 23 | 43 | 25 | 45 | 37 | 319 | 23 | |

| Ganglia | 0.005 | ||||||||||

| Non-metastatic | 353 | 39 | 62 | 33 | 50 | 29 | 34 | 28 | 499 | 36 | |

| Metastatic | 543 | 61 | 128 | 67 | 121 | 71 | 89 | 72 | 881 | 64 | |

Medial: Retroareolar; LOQ: lower outer quadrant; LIQ: lower inner quadrant; UOQ: upper outer quadrant; UIQ: upper inner quadrant.

In this study, we found a predominance of luminal A subtype (65%), triple negative subtype (14%), luminal B subtype (12%) and HER2 subtype (9%), slightly different to what was reported by Uribe and his team,10 who reported 60%, 29%, 9% and 2% respectively; while Arrechea et al.11 reported 62.5%, 8.4%, 18% and 9.9% and Calderón and his team12 reported 56%, 19%, 8% and 17%. In all the studies, luminal A subtype was the most frequent and exceeded 50%.

An association between subtypes and the patients’ age ranges was found between luminal A subtype and women aged 80–89. This can be explained, since positive hormone receptors are more common in postmenopausal women, as opposed to HER2 subtype, which was associated with age range 30–39, where positive hormone receptors are less common in premenopausal women.

Out of the risk factors, the most common one was late menopause (25%), but it was not associated with any subtype. Only HER2 subtype was associated with women who had never been pregnant.

The tumour characteristics associated with luminal A subtype were stages I and II, T1 and T2 size and non-metastatic ganglia. These characteristics have a better prognosis, as opposed to HER2 subtype, which was associated with stage III, T3 size, metastatic ganglia and mastectomy. These characteristics have a poorer prognosis.19–22

Luminal A and B subtypes represent more than 75% in which hormone therapy is indicated as another form of systemic treatment, although since luminal B subtypes are HER2+ they do not have the same response to hormone therapy as luminal A subtypes. Targeted therapy with trastuzumab monoclonal antibody is indicated for luminal B and HER2 subtypes, while for the triple negative subtype neither hormone therapy nor trastuzumab is indicated, only chemotherapy as systemic treatment.23–25

Information campaigns have been launched in the media to promote self-examination in women over the age of 25, as well as screening mammographies in women over the age of 40, with the purpose of diagnosing them at the early stages when the tumour is smaller than 1cm and can be treated efficiently; there is a survival rate over 95%, so mortality would be reduced. In this study, stage I represented only 9%.

ConclusionsIn this study, as in other studies, luminal A subtype is the most common one, over half of the cases; luminal A and B subtypes represent more than 3/4 parts. As for the other subtypes, there are slight differences that could be explained by the type of population under study. Luminal A is the one with the best prognosis, followed by luminal B, then HER2, and lastly triple negative. Out of the risk factors, late menopause was the most common one and it was identified in a quarter of the women. Out of the tumour characteristics, a size that is smaller than 2cm, stage I and non-metastatic ganglia are factors with a better prognosis and are associated with luminal A subtype, as opposed to tumours larger than 5cm, stage III and metastatic ganglia, which are factors with a poorer prognosis and are associated with HER2 subtype.

Conflict of interestsThe author declares that there are no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Pérez-Rodríguez G. Prevalencia de subtipos por inmunohistoquímica del cáncer de mama en pacientes del Hospital General Regional 72, Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social. Cir Cir. 2015;83:193–8.