Nesidioblastosis is a rare cause of endocrine disease which represents between 0.5% and 5% of cases. This has been associated with other conditions, such as in patients previously treated with insulin or sulfonylurea, in anti-tumour activity in pancreatic tissue of patients with insulinoma, and in patients with other tumours of the Langerhans islet cells. In adults it is presented as a diffuse dysfunction of β cells of unknown cause.

Clinical caseThe case concerns 46 year-old female, with a history of Sheehan syndrome of fifteen years of onset, and with repeated events characterised with hypoglycaemia in the last three years. Body scan was performed with octreotide, revealing an insulinoma in the pancreatic region. A distal pancreatectomy was performed on the patient. The study reported a pancreatic fragment 8.5cm×3cm×1.5cm with abnormal proliferation of pancreatic islets in groups of varying size, some of them in relation to the ductal epithelium. Histopathology study was showed positive for chromogranin, confirmed by positive synaptophysin, insulin and glucagon, revealing islet hyperplasia with diffuse nesidioblastosis with negative malignancy. The patient is currently under metabolic control and with no remission of hypoglycaemic events.

ConclusionsNesidioblastosis is a disease of difficult diagnosis should be considered in all cases of failure to locate an insulinoma, as this may be presented in up to 4% of persistent hyperinsulinaemic hypoglycaemia.

La nesidioblastosis constituye una causa rara de enfermedad endocrina, que representa entre 0.5% al 5% de los casos. Se ha descrito en asociación con otras condiciones, como en pacientes previamente tratados con insulina o sulfonilurea, en tejido pancreático no tumoral de pacientes con insulinoma, y en pacientes con otros tumores de las células de los islotes de Langerhans. En el adulto se presenta como una disfunción difusa de las células β, de causa desconocida.

Caso clínicoFemenina de 46 años, con síndrome de Sheehan de quince años de evolución y en los últimos tres años, presentó eventos repetidos caracterizados de hipoglucemia. Se realizó rastreo corporal con octreótide, revelando captación de región pancreática en relación con insulinoma. Se sometió a pancreatectomía distal. El informe fue de un fragmento de páncreas de 8.5×3×1.5cm con proliferación anormal de islotes pancreáticos en grupo de tamaño variable, algunos de ellos en relación al epitelio ductal. El estudio histopatológico mostró positividad para cromogramina, sinaptosina, insulina y glucagón en islotes hiperplásicos, que confirmó Nesidioblastosis difusa del adulto, negativo a malignidad. Actualmente la paciente se encuentra con adecuado control metabólico, y con remisión de los eventos de hipoglucemia.

ConclusionesLa nesidioblastosis es una patología de difícil diagnóstico, debe considerarse en todos los casos en donde no se logre la localización de un insulinoma, ya que esta puede estar presente hasta en el 4% de las hipoglucemias hiperinsulinémicas persistentes.

In 1938 George Laidlaw coined the term nesidioblastosis to refer to the neoformation of Langerhans islet cells from the exocrine pancreatic ductal epithelium; however, it was not until 1971 that Yakovac used this term to describe lesions of the endocrine pancreas in infants, when he reported 12 cases of children with persistent hyperinsulinaemic hypoglycaemia. At present, the nesidioblastosis of the pancreas in adults is defined as changes in the endocrine pancreas characterised by the abnormal proliferation of the pancreatic islet cells that affect the gland in a diffuse manner budding off from the ductal epithelium and causing persistent hyperinsulinaemic hypoglycaemia in absence of insulinoma.1–4

Clinical caseA 46-year-old female with 15 years history of Sheehan's syndrome evolution, treated with 100mcg of levothyroxine and 5mg of prednisone/24h. She went to hospital because of exacerbation of a 3-year history of a clinical condition of repeated events characterised by nausea, dizziness, diaphoresis, palpitations, and loss of alertness associated with hypoglycaemia, which reverted with the intake of simple sugars.

On physical examination she presented blood pressure of 120/70mmHg, heart rate of 70bpm, body weight of 70kg, height was 155cm, BMI of 29kg/m2; and the rest of the physical exploration was within normal parameters. The laboratory studies reported haemoglobin was 14.2g/dl; haematocrit, 39.4%; platelet, 287,000; leukocytes, 9300; glucose, 69mg/dl; urea, 28mg/dl; creatinine, 0.7mg/dl; free T4, 1.22ng/dl, and thyroid-stimulating hormone was 0.2μUI/ml. A fasting test was performed which showed the presence of endogenous hyperinsulinism with blood sugar levels of 52mg/dl in absence of adrenergic and/or neuroglycopenic symptoms, insulinaemia of 7.61μU/ml, C peptide of 6.5ng/dl, and proinsulin of 5.8pmol/l at 72h.

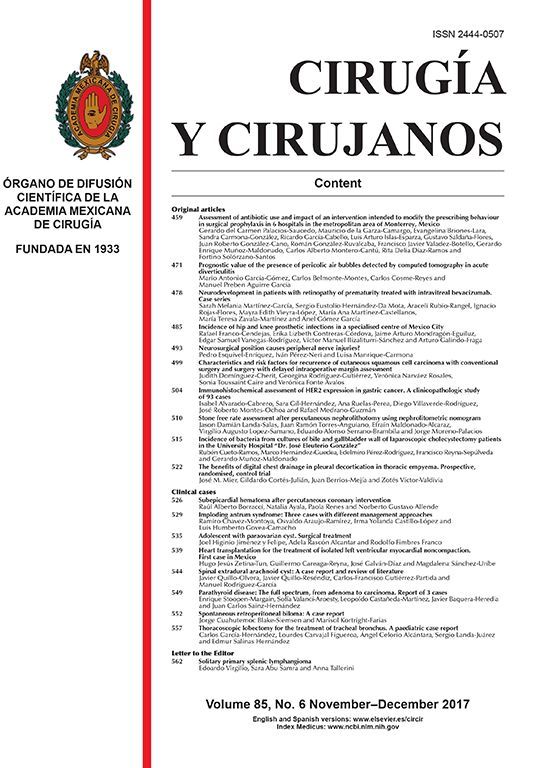

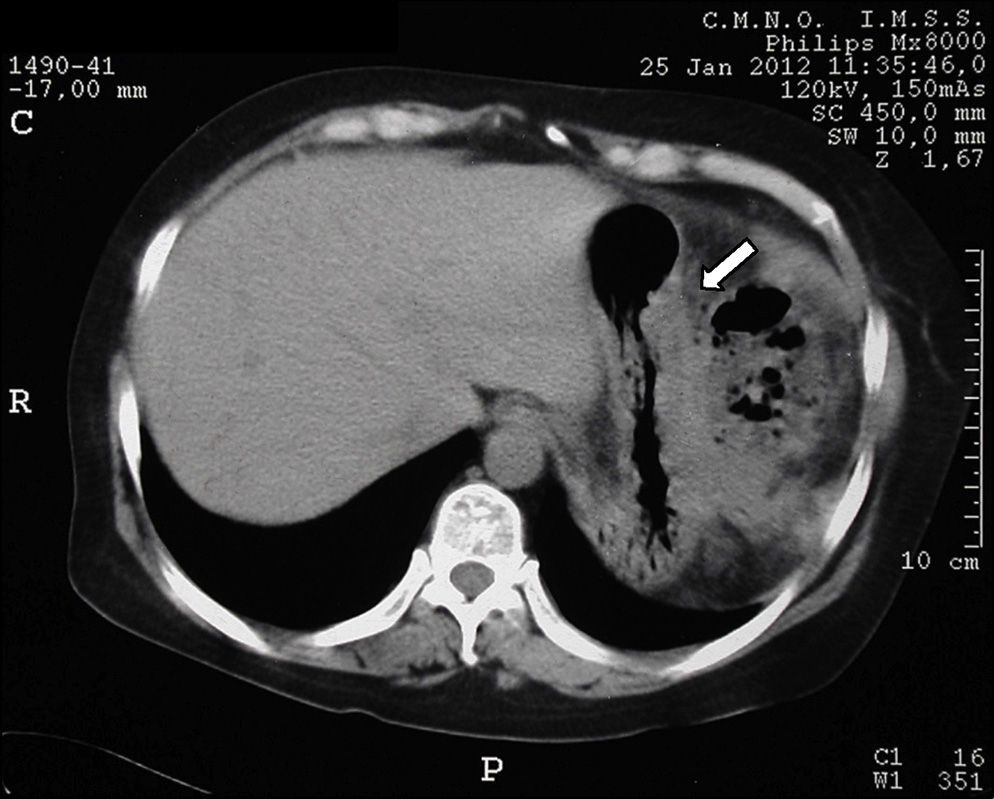

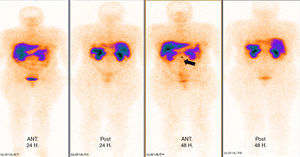

Tomography imaging studies did not show evidence of disease in the pancreas (Fig. 1). A body scan performed with octreotide showed pancreatic capture towards middle line; and the rest of the scan showed no evidence of lesions that may suggest metastatic activity (Fig. 2).

From the imaging studies findings, the patient was submitted to a pancreatic exploration; however, no suspicious nodular lesions were located on palpation or macroscopic examination and the pancreatic gland presented normal characteristics, and therefore a distal pancreatectomy at the level of the mesenteric vessels was performed.

The glucose level stayed normal. During the immediate postoperative period the patient presented glucose concentrations in venous blood of 100 and 130mg/dl, which prompted the administration of rapid insulin.

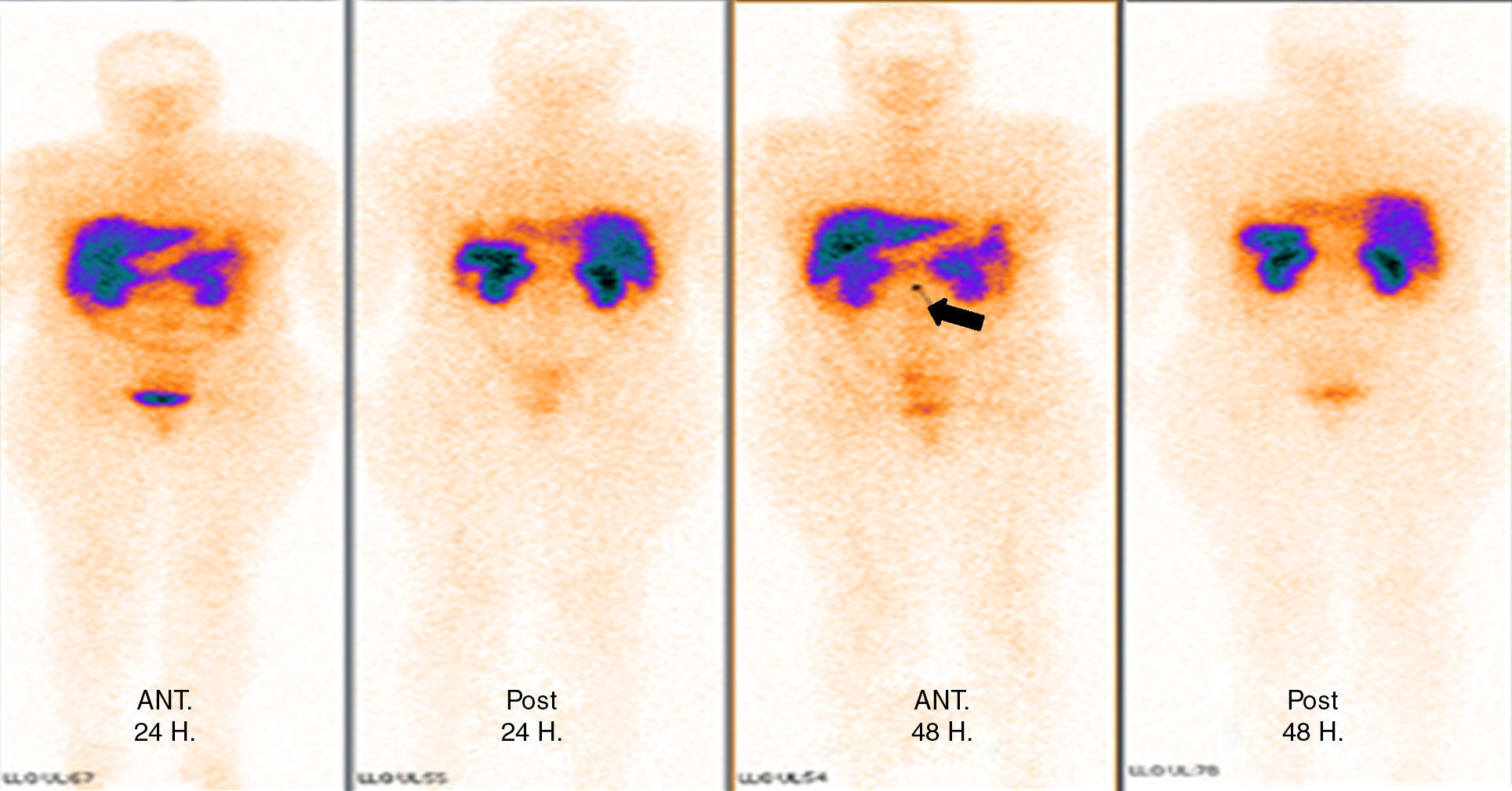

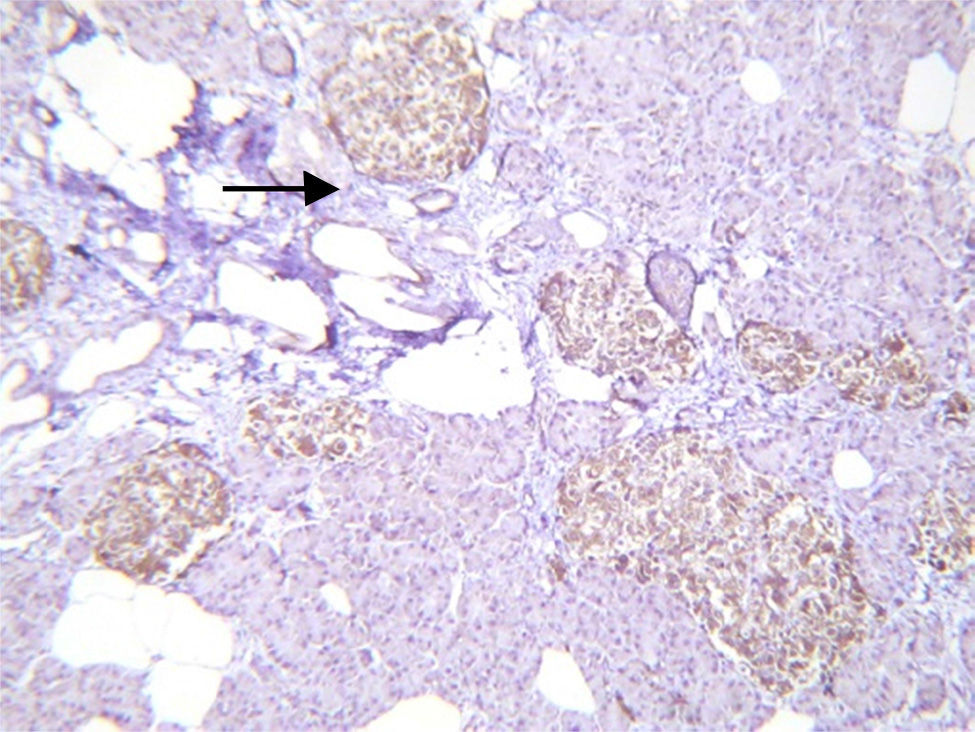

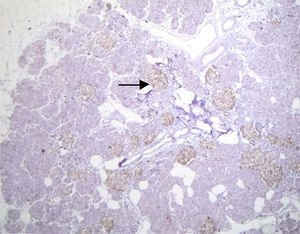

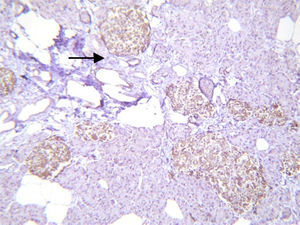

Histopathological study and macroscopic examination reported a pancreatic fragment of 8.5cm×3cm×1.5cm, of yellow colour, with a trabecular surface, with areas of greater congestion. Microscopic examination showed abnormal proliferation of pancreatic islets disposed in groups of variable sizes, some of which were related to the ducal epithelium and forming hyperchromatic, enlarged ductal complexes with ample clear cytoplasm. Immunohistochemistry revealed that the hyperplastic islets were positive for chromogranin A with peripheral concentration, diffuse synaptophysin, glucagon in the periphery of the islets and in the α cells, and insulin of diffuse form in the intra-acinar cells (Figs. 3 and 4). Clinical, radiological, histologic and immunohistochemical criteria were collected to determine the diagnosis of diffuse nesidioblastosis in the adult, negative for malignancy. At present, the patient presents a good metabolic control, with remission of the hypoglycaemia events.

The persistent hyperinsulinaemic hypoglycaemia is caused by the alteration in the pancreatic β cell function, mainly caused by nesidioblastosis in newborns. In adults, most of the hyperinsulinaemic hypoglycemia cases are caused by isolated insulinomas, the nesidioblastosis being responsible for only 0.5–5% of the cases. The first case of nesidioblastosis in an adult was reported in 1975.2,3

Several genetic abnormalities have been identified as associated with the pathogenesis of persistent hyperinsulinaemic hypoglycaemia in infancy, the most frequent being mutations of the genes ABCC8 (SUR1) and KCNJ11 (Kir6.2), in the chromosome 11 short arm, which encode the sub-units of ATP-sensitive potassium channels in the cell membrane β, producing a permanent insulin secretion. Also, 6 other possible causes have been identified recently, such as loss of function due to mutations in glucokinase (GCK), glutamate dehydrogenase (GLUD1), hydroxyacyl CoA dehydrogenase (HADH1), plasmatic membrane pyruvate transporter (SLC16A1), mitochondrial-uncoupling protein (UCP2), and hepatocyte nuclear factors (HNF4a). Although it is true that these alterations have not been reported in adults, it is important to note that mutations such as GLUD1, GCK, SLC16A1, and some slight ABCC8 and KCNJ11 mutations may not be detected during childhood but may be recognised for the first time during adulthood, as it is not infrequent that subjects are diagnosed during childhood or even after it.5,6

The morphological substrate of these molecular changes can appear in children as diffuse cell hypertrophy β (diffuse nesidioblastosis) in 60% or as focal cell hypertrophy β (focal nesidioblastosis) in 40%; however, this last presentation has not been described in adults.1,2

In adults, the nesidioblastosis was initially described as being associated with other diseases, such as Zollinger–Ellison syndrome, multiple endocrine adenomatosis, cell adenomatosis β, Von Hippel–Lindau disease, cystic fibrosis, orbital lymphoma with hypopituitarism and adrenal insufficiency, familial adenomatous polyposis, hypergastrinaemia and pancreatic polypeptidemia, in non-tumour pancreatic tissue of patients with insulinomas. With the increase of bariatric surgery, particularly the gastric bypass, and although the pathophysiological effect of this is still unclear, it has been observed that in these patients higher levels of polypeptide with trophic effect on the β cell, as the glucagon-like peptide 1, contributes to the pancreatic cellular hypertrophy β and, consequently, to the islets hyperfunction, which results in the postprandial hypoglycaemia.2,7,8

It is not clinically or biochemically possible to distinguish the nesidioblastosis from the insulinoma, and it is necessary that both clinicians and pathologists work closely together to determine the diagnosis. It is also essential to rule out the diagnosis of insulinoma beforehand.3

Some patients present hypoglycaemia symptoms, predominantly postprandial, when not fasting, as it usually occurs in patients with persistent hyperinsulinaemic hypoglycaemia secondary to insulinoma. However, most of the patients present typical hypoglycaemia symptoms (Whipple's triad); adrenergic symptoms, such as diaphoresis, palpitations, anxiety, tremor, sensation of hunger, and neuroglycopaenia symptoms, such as confusion, blurred vision, amnesia, and loss of consciousness.2

The ideal reference test to evaluate the presence of hypoglycaemia is the 72h fast period, with the aim of assessing the role of insulin in the genesis of hypoglycaemia. In our patient, this test evidenced the presence of endogenous hyperinsulinism, which prompted the performance of imaging studies to localise the lesion.

Computed axial tomography did not demonstrate the presence of a lesion; therefore, an octreoscan was then performed, and the presence of an image suggestive of a lesion in the pancreatic neck, with high levels of contrast uptake was shown. However, clinically, the patient presented Whipple's triad with hypoglycaemia symptoms, low level of blood glucose, which responded to intravenous glucose administration, and increased serum levels of insulin. This generated the clinical suspicion that the patient had an insulinoma. On the possibility of the probable presence of insulinoma, the protocol for the resection of the lesion was started.6,9,10

Surgical resection is considered to be the treatment of choice for nesidioblastosis. However, the extension of it is still controversial.11,12 Most surgeons perform distal pancreatectomy; some have even conducted 90–95% pancreatectomy; but, according to some authors, a subtotal pancreatectomy is associated with insulin-dependent diabetes and exocrine pancreatic dysfunction in 40%; with resection of 60% of the pancreas, 8% of the patients will present insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, but with higher recurrence rates of hypoglycaemia. If surgery is not successful or is contraindicated, drugs such as diazoxide, octreotide or verapamil can be used. Our patient was surgically managed with a distal pancreatectomy, resecting the 70% of the pancreas, and the result was secondary diabetes mellitus. She stayed within the 8% of the cases reported by the medical bibliography, aggravated by the treatment with corticosteroids administered for her Sheehan's syndrome.6,10,13

In the histopathological study, the macroscopic presentation of the pancreas is normal; the finding varies among the patients and up to the third part of the cases, the changes are minimum. For this reason, it is difficult to differentiate them from normal pancreas.11,14,15

Other findings in patients with nesidioblastosis have been reported, such as an insulin-like growth factor type 2 over-expression, type 1 insulin-like growth factor receptor, transforming growth factor β β3, and peliosis-type vascular ectasia. This is very useful for diagnosis. In our case, we found hyperplasia of the Langerhans islets with no tumour, ductal epithelium hyperplasia, excluding macroscopic and microscopic diagnosis of insulinoma, with islets of irregular shapes and enlarged in number and size. All the above, allowed us to conclude that the diagnosis was diffuse nesidioblastosis in adult.2,10,11,16

ConclusionNesidioblastosis is a disease of difficult diagnosis that should be considered in all the cases where it is not possible to find insulinoma, as this may be presented in up to 4% of persistent hyperinsulinaemic hypoglycaemia. Early identification and diagnosis play an essential role in the prognosis of the disease.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Ramírez-González LR, Sotelo-Álvarez JA, Rojas-Rubio P, Macías-Amezcua MD, Orozco-Rubio R, Fuentes-Orozco C. Nesidioblastosis en el adulto: reporte de un caso. Cir Cir. 2015;83:324–328.