Hepatic adenomas are uncommon epithelial tumours. They usually appear in women between 20 and 44 years old. They are commonly located in the right hepatic lobe and are typically solitary masses. Multiple adenomas can present in patients with prolonged use of oral contraceptive pills, glycogen storage diseases and hepatic adenomatosis.

Clinical caseA 35 year-old woman without any significant past medical history, with a chief complaint that started in December 2012 with oppressive, mild intensity abdominal pain located in right upper quadrant in the abdomen on deep palpation. With an abdominal ultrasound showing a mass of 91cm×82cm×65cm located in the right flank, isoechogenic with internal vascularity. Contrast computed tomography scan showing an ovoid tumour with circumscribed borders, with heterogenic intense reinforcement and displacement of adjacent structures with dimensions of 88cm×71cm×80cm. In laparotomy, excision of the tumour and cholecystectomy with the trans surgical findings of an 8cm tumour with a pedicle containing one artery and one vein coming from the hepatic free border with strong adhesions to the gallbladder. Pathologic diagnosis: extracapsular hepatic adenoma.

ConclusionsIncidence of hepatic adenomas has increased in the last decades, in a parallel fashion with the introduction of oral contraceptive pills, showing association with glycogen storage diseases and to a lesser degree with diabetes and pregnancy. Diagnosis is clinical with the aid of imaging studies. Prognosis of hepatic adenomas is not well established, therefore, management depends on symptoms, size, number, location and certainty of diagnosis.

Los adenomas hepáticos son tumores epiteliales poco comunes. Usualmente aparecen en mujeres de 20 a 44 años; con frecuencia están localizados en el lóbulo hepático derecho y son típicamente solitarios. Los adenomas múltiples suelen presentarse en pacientes con uso prolongado de anticonceptivos orales, enfermedades de almacenamiento de glucógeno y adenomatosis hepática.

Caso clínicoPaciente femenina de 35 años sin antecedentes de importancia. Inició el padecimiento motivo de consulta en diciembre del 2012, con dolor abdominal opresivo de mediana intensidad en hipocondrio derecho. A la exploración de abdomen, se observa tumoración abdominal en flanco derecho y dolor a palpación profunda. El ultrasonido abdominal con tumoración de 91×82×65cm localizada en flanco derecho, isoecoica con vascularidad interna. La tomografía axial computada contrastada abdominal muestra tumor ovoide de bordes delimitados, y reforzamiento intenso heterogéneo que desplaza estructuras adyacentes, con diámetros de 88×71×80cm. Se realizó laparotomía con exéresis de tumor y colecistectomía con hallazgos transquirúrgicos: tumor de 8cm de diámetro, con pedículo que incluye vena y arteria nutricia proveniente de borde hepático, adherido a vesícula biliar. Diagnóstico histopatológico de adenoma hepático extracapsular.

ConclusiónLa incidencia de los adenomas hepáticos se ha incrementado en las últimas décadas, de forma casi paralela a la introducción de los anticonceptivos orales, además de asociarse con enfermedades de almacenamiento de colágeno y, de forma menos común, con diabetes mellitus y embarazo. El diagnóstico es clínico con ayuda de estudios de imagen. El pronóstico de los adenomas hepáticos no está bien establecido. El tratamiento se establece de acuerdo con los síntomas, tamaño, número, localización y la certeza en el diagnóstico.

Hepatic adenomas are benign epithelial tumours of the liver that develop in apparently normal tissue. They predominate in women aged from 20 to 44 years and in the right hepatic lobe. Most are solitary (in 80–90% of cases) and the size can vary from 1cm to 30cm. The presence of abdominal pain is generally associated with larger tumours.1

The prognosis for hepatic adenoma has not been established, since these types of tumour can undergo malignant transformation, spontaneous haemorrhage and rupture.

It is important to differentiate hepatic adenoma from other types of benign tumour and definitive diagnosis is made by histopathological study of the surgical piece.

The association between oral contraception and liver tumours was described by Baum et al. in 1973.2 There are studies that have demonstrated the association between doses and duration of hormone therapy with the presentation of these types of tumour.3

Most adenomas are detected incidentally in patients undergoing ultrasound, tomography or magnetic resonance procedures for a different reason, or they can manifest with non-specific or unrelated symptoms.

The annual incidence of hepatic adenoma is approximately one per million in women who have never used oral contraceptives, compared with 30–40 per million in patients who have used oral contraception for long periods of time.4 Oral contraceptives also affect the natural history of hepatic adenoma, and they have been observed to make them more numerous, larger and more prone to bleeding.5 In addition, regression of adenoma has been observed after discontinuing oral contraception with recurrence during further hormonal stimulus.6 Oestrogens are thought to cause the direct transformation of hepatocytes through steroid receptors.7

Development of hepatic adenoma has also been associated with anabolic androgenic steroids and with anabolic steroids used for the treatment of impotence, Fanconi syndrome and muscle development in body-builders and transsexual people.8

Development of this neoplasm has been observed with glycogen storage diseases types I and III9; and resolution of the problem has been reported in some patients after dietary therapy and correction of insulin, glucose and glycogen levels.

An association between pregnancy and hepatic adenoma has been made due to the increased endogenous levels of sexual steroids.10

Maternal mortality can present in up to 59%, and foetal mortality can be 62% in cases that present rupture of hepatic adenoma and pregnancy.11

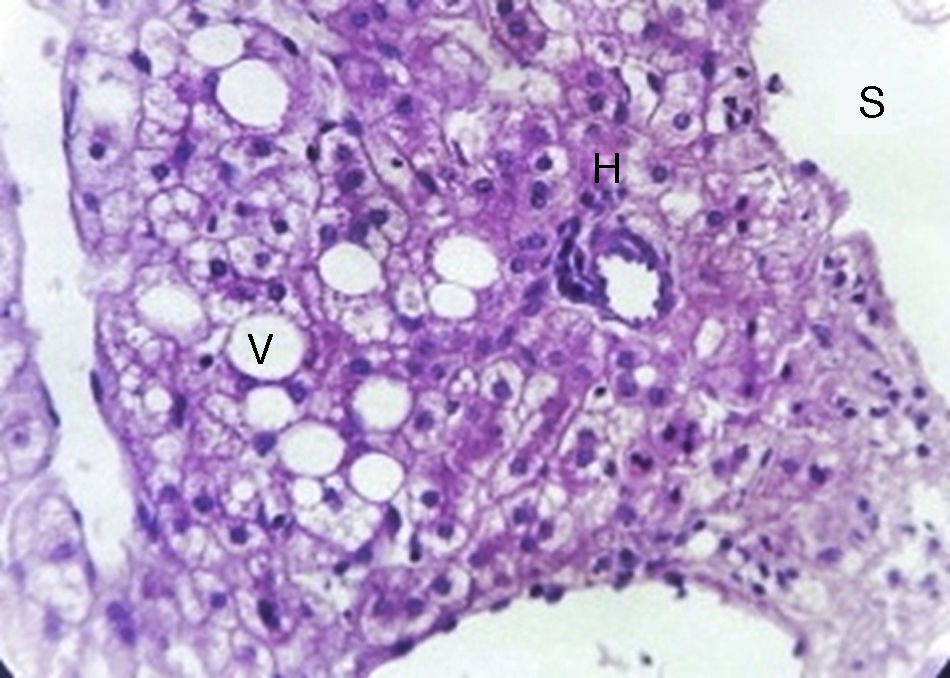

Microscopically, hepatic adenoma are composed of large plates of adenoma cells, which are typically larger than normal hepatocytes and contain glycogen and lipids. The nuclei are small and regular, the mitoses are rarely visible. There is notable absence of normal hepatic architecture and the cells are arranged in normal or thickened trabeculae interspersed with prominent arteries with thin-walled blood vessels and sinusoids. Septa, portal tracts and bile ductules are absent, this characteristic helps distinguish it from non-neoplastic hepatic tissue and focal nodular hyperplasia. It is sometimes difficult to distinguish hepatocellular carcinoma, but this can be done from the trabecular pattern of the tumour cells.12

Clinical case35-year-old female with no significant history. The condition started in December 2012 with the gradual onset of stabbing pain of 3/10 intensity and the patient subsequently noticed the presence of a palpable tumour in the right hypochondrium, which was more evident with posture changes, essentially associated with flexion of her spinal column; she did not report any other symptoms. She was sent by her family medical unit to general surgical outpatients for this reason.

Physical examinationIn good general condition, conscious, oriented, with a BMI of 26.3kg/m2. No apparent cardiopulmonary compromise, distended abdomen due to adipose panniculus, with the presence of a palpable tumour at the level of the right hypochondrium, not delimited, profound and mobile, with a diameter of approximately 6cm, of firm consistency and 5/10 pain on palpation, no signs of peritoneal irritation. The rest of the physical examination was normal.

Laboratory test reportHaemoglobin 13.1g/dL, haematocrit 39.2%, leukocytes 6000mm–3, neutrophils 58%, platelets 153,000mm–3, glucose 78mg/dl, creatinine 0.5mg/dl, Na 136mEquiv./l, K 4.2mEquiv./l, Cl 111mEquiv./l, alpha-fetoprotein 5ng/dl, total bilirubin 0.4mg/dl, carcinoembryonic antigen <2.5ng/ml, alkaline phosphatase 35mU/dl, gamma glutamyl transpeptidase 21mU/ml, lactate dehydrogenase 142mU/ml, aspartate aminotransferase 15mU/ml, alanine aminotransferase 12mU/ml, prothrombin time 11.2s, partial thromboplastin time 23s, INR 0.92.

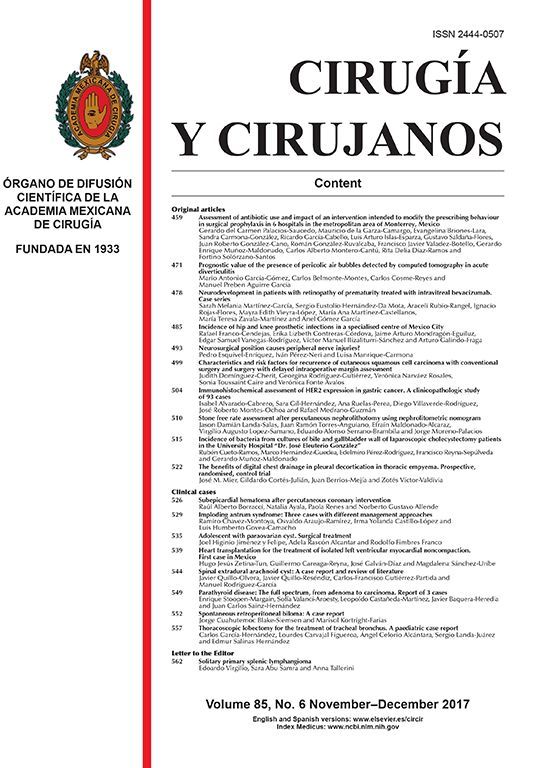

The study protocol was started with abdominal ultrasound which reported the presence of a tumour 91cm×82cm×65cm in diameter, on the right flank, isoechoic, with internal vascularity, well delimited, with no signs of intraperitoneal free fluid. Subsequently a plain abdominal CT was performed, reporting an ovoid tumour of delimited borders and contrast enhanced, heterogeneously intense, displacing adjacent structures (Fig. 1), with diameters of 88cm×71cm×80cm.

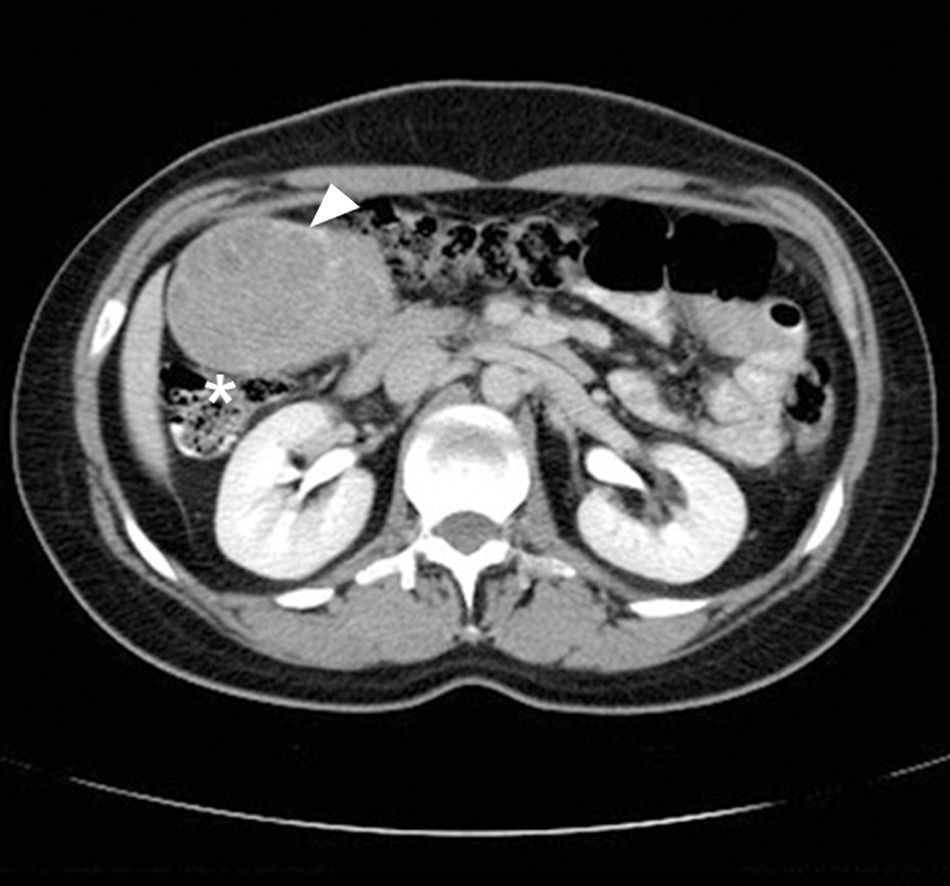

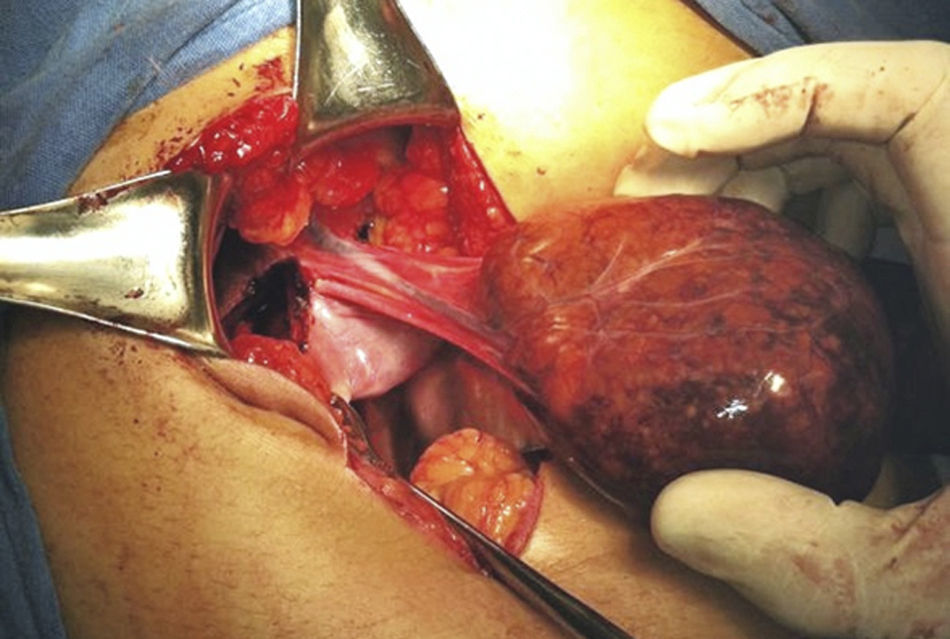

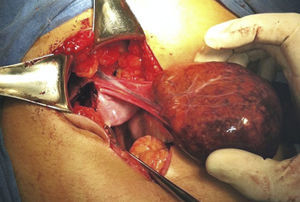

With the complete protocol, exploratory laparotomy was decided in order to remove the tumour and perform a cholecystectomy (Fig. 2). Transurgical findings were of a tumour, 8cm in diameter with a pedicle containing a vein and nutrient artery coming from the free liver margin, firmly adhering to the gallbladder. The surgical piece with the gallbladder are shown (Fig. 3). The pathology department reported the presence of parenchyma with macro and micro-nodules (Fig. 4), which were well delimited and independent of the gallbladder, with preservation of the functional unit, but with loss of architecture and disorganised portal triad, with changes suggestive of hepatic steatosis (Fig. 5). Therefore, a histopathologic diagnosis of extracapsular hepatic adenoma was made.

During her hospital stay the patient presented no postoperative complications and was therefore discharged home. She was seen a month later in general surgery outpatients and reported that she was free from symptoms. She was then discharged from the department.

DiscussionThe incidence of hepatic adenoma is one per million in women who have never used oral contraception (as in the case of our patient) and, although they are typically diagnosed due to abdominal pain in the epigastrium or upper right quadrant, in this case the patient met the criterion of abdominal pain and had a palpable tumour in the right hypochondrium. She therefore underwent imaging studies and a tumour was detected.

Unfortunately many diagnoses are made from imaging studies performed for a different reason, or on physical examination, and these adenomas can manifest with collapse associated with rupture and intra-abdominal bleeding.

Episodic abdominal pain, located in the epigastrium or the upper right quadrant can indicate an enlarged liver, bleeding in the tumour or necrosis. The onset of severe pain associated with hypotension indicates rupture towards the peritoneal cavity. A mortality of up to 20% has been reported if this occurs and is not promptly identified.13

It is difficult to establish the risk of bleeding; it can be as high as 25–64%.14 Abdominal pain, a long history of contraceptive use, subcapsular location and adenoma larger than 35mm in size are characteristics associated with an increased risk of bleeding. An abdominal tumour can be identified in up to 30% of patients, whereas hepatomegaly presents in 25%.15 This tumour is pedunculated in 10%, as in the case that we present. They are generally smooth and tan colour in appearance, with large vessels on the surface of the tumour and areas of haemorrhage and necrosis inside. They do not usually have a fibrous capsule and haemorrhage from an adenoma can spread inside the liver or directly towards the peritoneum, if it is pedunculated.

Abnormalities in liver function tests are rare; there can be elevated alkaline phosphatase and gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase levels, particularly in patients with intra-tumour bleeding or multiple adenomas. Alpha fetoprotein is normal except in patients where it has turned malignant, and the risk of developing hepatocellular carcinoma has been reported as 8–13%.16

There is another related clinical entity termed hepatic adenomatosis, which is characterised by the presence of more than 10 adenomas, lack of correlation with steroid medication or the condition failing to resolve after their withdrawal, and lack of association with glycogen storage diseases. This entity affects both males and females, with an abnormal increase in alkaline phosphatase and gamma glutamyl transpeptidase levels.17 The conditions that predispose to adenomatosis are not well understood. One theory is that the development of adenomatosis is associated with congenital or acquired abnormalities of the hepatic vasculature.18 The natural history of adenomatosis is not well understood, since the available information comes from individual reports and small case series.19,20

Hepatic adenoma should be diagnosed based on the clinical context, a combination of imaging studies and surgical resection. Percutaneous or fine-needle aspiration biopsy is usually not indicated because of the tendency to bleed, and insufficient amount of sample for analysis. How to differentiate hepatic adenoma from focal nodular hyperplasia is a common dilemma. Although imaging characteristics can help differentiate them, surgical resection is usually necessary to reach a definitive diagnosis and can be curative at the same time. As an initial imaging study, ultrasound can offer certain information, such as necroses that can appear as hyperechoic areas with acoustic shadows.21 Colour Doppler ultrasound can differentiate focal nodular hyperplasia due to the presence of intra tumour and peri tumour vessels with an absence of signal from a central artery.22

Computed tomography has the advantage of obtaining both contrast-enhanced and non contrast-enhanced image phases, enabling a dynamic sequence for evaluating a focal hepatic lesion. Scans with contrast can show an increased uptake in the periphery during an early phase with subsequent centripetal flow during the portal venous phase, which is characteristic of adenomas.1 The areas of haemorrhage, necrosis or fibrosis give then a heterogeneous appearance.

On magnetic resonance, hepatic adenomas are well delimited due to the presence of fat or glycogen from the hepatocytes. Most adenomas are hyperintense on T1 images due to the presence of fat or glycogen and in T2 images, the presence of images that enhance after administering gadolinium are highly suggestive and facilitate diagnosis.23 On technetium-99 scan, a minority of tumours take up the radiotracer, making them indistinguishable from focal nodular hyperplasia.24 MR can be useful within the clinical context and results of other radiological tests indicate a diagnosis of focal nodular diagnosis.

Amongst the contrast studies, angiography is rarely used in diagnosing hepatic adenomas. Approximately half these neoplasms have characteristics typical of a well-circumscribed tumour with increased peripheral vascularity.

Decisions for treating these tumours depend on symptoms, size, number and location, and diagnostic certainty. Some authors support a conservative approach in patients with small lesions (<5cm). Resection of symptomatic hepatic adenomas is recommended. Lesions that do not resolve or that increase in size after withdrawal of steroid medication should be considered for surgical resection after discussing this with the patient.

The behaviour of adenomas in pregnant women is unpredictable and the best option is to resect the lesion prior to a pregnancy. An adenoma that ruptures during pregnancy should be managed with the appropriate resuscitation and surgical resection. Due to the risk of rupture, surgical resection should be recommended for patients with large or symptomatic adenomas. Resection should ideally be performed during the second trimester, during which there is minimal risk to mother and foetus.25 Surgical treatment is recommended for patients with symptoms that can be attributed to an adenoma and with lesions larger than 5cm.26 Surgical options include: enucleation, resection and, rarely, liver transplantation.

Liver transplantation should be reserved for patients for whom surgical resection is not possible, due to the location or size of the tumour or due to the presence of adenomatosis.27 Mortality after elective surgical resection is less than 1% and some adenomas located in the periphery can be resected laparoscopically.28 Patients who present abdominal pain and arterial hypotension as a result of intraperitoneal bleeding due to a ruptured adenoma have a mortality of up to 20%. These patients should be operated for definitive resection and to control bleeding.

Emergency surgery is associated with a mortality of 5–8%.29

In this clinical case, the treatment administered by surgical resection totally resolved the patient's symptoms, because histopathological study confirmed the absence of malignancy and therefore avoided any possible complications associated with the spontaneous rupture of the hepatic adenoma directly into the peritoneal cavity.

ConclusionsThe association of hepatic adenomas with the concomitant administration of oral contraceptives, collagen storage diseases, diabetes mellitus and other situations with hormonal changes such as pregnancy, raise suspicions of a neoplasm of this type when the patient presents ill-defined clinical manifestations or pain in the upper right quadrant. However, as in the patient in our clinical case, who did not have a history of this type, such a background has been demonstrated not to be an obligatory requirement for these neoplasms to develop.

Despite the fact that they are often identified as a finding on imaging studies, their association with the patient's history and symptoms should immediately alert the doctor and resection should be considered given the risk of spontaneous rupture and malignant transformation. For the patient in this clinical case, the determining factors for resection were the symptoms, the size of the neoplasm, its potential risk of rupture and malignant transformation.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Vargas-Flores E, Pérez-Aguilar F, Valdez-Mendieta Y. Adenoma hepático extracapsular. Reporte de un caso y revisión de la bibliografía. Cir Cir. 2017;85:175–180.