The complications of otitis media (intra-cranial and extra-cranial) used to have a high morbidity and mortality in the pre-antibiotic era, but these are now relatively rare, mainly due to the use of antibiotics and the use of ventilation tubes, reducing the incidence of such complications significantly. Currently, an early suspicion of these complications is a major challenge for diagnosis and management.

Clinical casesThe cases of 5 patients (all male) are presented, who were diagnosed with complicated otitis media, 80% (4) with a mean age of 34.6 years (17–52). There was major comorbidity in 60% (3), with one patient with diabetes mellitus type 2, and two with chronic renal failure. There were 3 (60%) intra-cranial complications: one patient with thrombosis of the sigmoid sinus and a cerebellar abscess; another with a retroauricular and brain abscess, and a third with meningitis. Of the 2 (40%) extra-cranial complications: one patient had a Bezold abscess, and the other with a soft tissue abscess and petrositis. All patients were managed with surgery and antibiotic therapy, with 100% survival (5), and with no neurological sequelae. The clinical course of otitis media is usually short, limiting the infection process in the majority of patients due to the immune response and sensitivity of the microbe to the antibiotic used. However, a small number of patients (1–5%) may develop complications.

ConclusionOtitis media is a common disease in our country, complications are rare, but should be suspected when the picture is of torpid evolution with clinical worsening and manifestation of neurological signs.

Las complicaciones de la otitis media (intracraneales y extracraneales) tuvieron alta morbimortalidad en la era preantibiótica. En la actualidad son relativamente raras con el uso de antibióticos, tubos de ventilación y otros cuidados médico-quirúrgicos, reduciendo la incidencia de forma notable. Actualmente la sospecha oportuna de estas complicaciones es indispensable y constituye un gran reto para su diagnóstico y tratamiento adecuados.

Casos clínicosPresentamos 5 pacientes con diagnóstico de otitis media aguda complicada, el 100% (5) fueron de sexo masculino; el 80% (4) con edad media de 34.6 años (17-52), y la comorbilidad fue importante en el 60% (3): un paciente con diabetes mellitus tipo 2 y 2 con insuficiencia renal crónica terminal. Tres pacientes (60%) tuvieron complicaciones intracraneales: un paciente con trombosis del seno sigmoides y absceso cerebeloso, otro con absceso retroauricular y cerebral, y un tercero con meningitis. Dos pacientes (40%) tuvieron complicaciones extracraneales: un paciente con absceso de Bezold y otro con absceso de tejidos blandos y petrositis. Todos fueron tratados con manejo quirúrgico y antibioticoterapia con supervivencia del 100% (5), sin secuelas neurológicas. El curso clínico de la otitis media aguda suele ser corto, limitándose el proceso infeccioso en la gran mayoría de los pacientes debido a la respuesta del sistema inmune y de la sensibilidad del germen al antibiótico utilizado. Sin embargo, un pequeño número de pacientes pueden presentar complicaciones (1-5%).

ConclusiónLa otitis media aguda es una enfermedad muy frecuente en nuestro medio. Sus complicaciones son raras, sin embargo se deben de sospechar cuando la evolución del cuadro es tórpida con empeoramiento clínico y manifestación de signos neurológicos.

In the pre-antibiotic era morbidity and mortality from acute otitis media was very high, because of the high frequency of intracranial and extracranial complications. Nowadays these complications are relatively rare and ongoing suspicion is required for diagnosis.1 Mastoiditis is a serious complication of acute otitis media that is more common in paediatric patients, under the age of 4. Within its pathophysiology, its complications can develop due to contiguity or vascular invasion, and the infection can reach the central nervous system. Complications can be subperiosteal abscess, Bezold abscess, facial paralysis, suppurative labyrinthitis, meningitis, epidural, subdural/cerebellar abscess, sigmoid sinus thrombosis and otitic hydrocephalus, some of which are potentially fatal. Management of acute mastoiditis varies and includes conservative treatment using parenteral antibiotics, myringotomy (with or without placement of ventilation tubes) or surgical intervention (more aggressive and including mastoidectomy).2,3

ObjectiveThe objective of the study was to describe the cases of complications of otitis media that presented in the Centro Médico Nacional de Occidente in 2014.

Material and methodsA case series with retrospective analysis of 5 cases from the ENT Department. The study included adult patients with complications of otitis media attended in a third level hospital between January and December 2014. The patients’ files were reviewed to verify diagnosis, complications, treatment, mortality and survival.

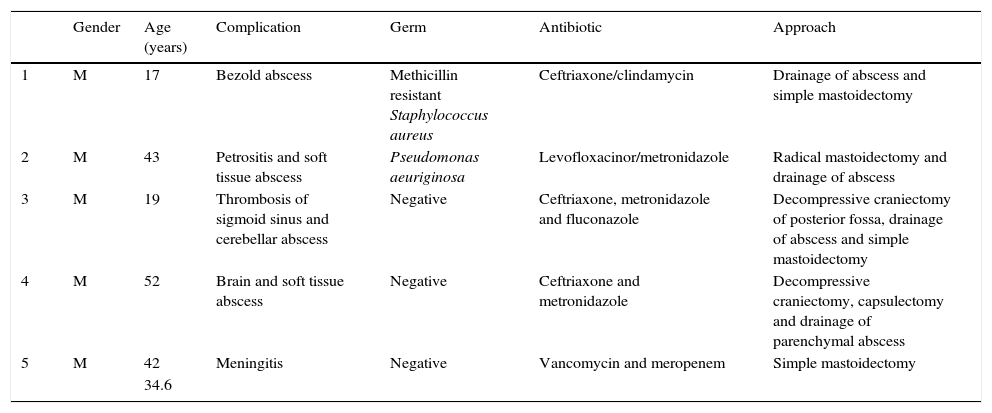

ResultsFive cases were presented of complicated otitis media with a mean age of 34.6 (17–52), 100% (5/5) were male, 60% (3/5) were immunosuppressed. The clinical diagnosis was confirmed in all cases by computed tomography (CT scan). All of the patients were initially treated with empirical antimicrobial therapy and subsequently treated according to the results of the antibiogram. Eighty percent of the cases underwent simple mastoidectomy and 20% (1/5) radical mastoidectomy. Eighty percent required multidisciplinary care, 40% underwent decompressive craniectomy and drainage of intracranial abscess; 100% survival was achieved, therefore 0% mortality (Table 1).

Outcomes of complications of otitis media.

| Gender | Age (years) | Complication | Germ | Antibiotic | Approach | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | 17 | Bezold abscess | Methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus | Ceftriaxone/clindamycin | Drainage of abscess and simple mastoidectomy |

| 2 | M | 43 | Petrositis and soft tissue abscess | Pseudomonas aeuriginosa | Levofloxacinor/metronidazole | Radical mastoidectomy and drainage of abscess |

| 3 | M | 19 | Thrombosis of sigmoid sinus and cerebellar abscess | Negative | Ceftriaxone, metronidazole and fluconazole | Decompressive craniectomy of posterior fossa, drainage of abscess and simple mastoidectomy |

| 4 | M | 52 | Brain and soft tissue abscess | Negative | Ceftriaxone and metronidazole | Decompressive craniectomy, capsulectomy and drainage of parenchymal abscess |

| 5 | M | 42 | Meningitis | Negative | Vancomycin and meropenem | Simple mastoidectomy |

| 34.6 |

M: male.

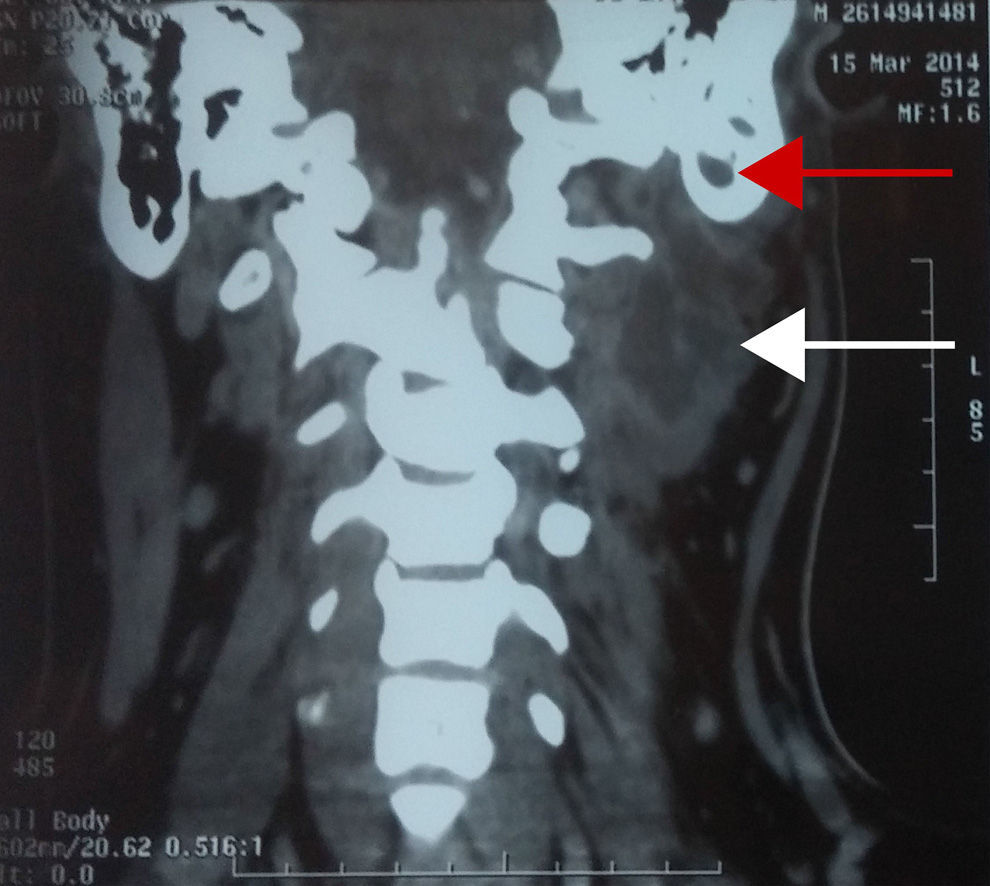

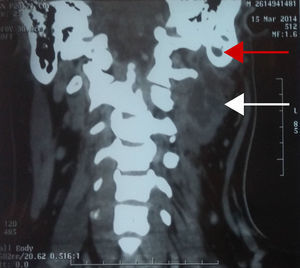

A 17-year-old male patient, referred to the ENT and Head and Neck Surgery Department with increased volume in the posterior triangle of the left side of the neck, with a history of acute otitis media. CT scan confirmed diagnosis of mastoiditis complicated with Bezold abscess. The patient was managed surgically with drainage of the abscess via the transcervical approach and simple mastoidectomy (Fig. 1).

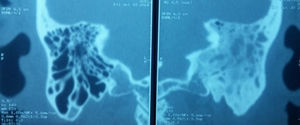

Case 2A 43-year-old male patient with a history of chronic kidney disease receiving replacement therapy with haemodialysis. The patient presented with increased volume in the right retroauricular region and a 15-day history of otorrhoea. Imaging study confirmed the diagnosis of otitis media complicated by soft tissue abscess and petrositis. Therefore a radical mastoidectomy was performed and drainage of soft tissue abscess (Fig. 2).

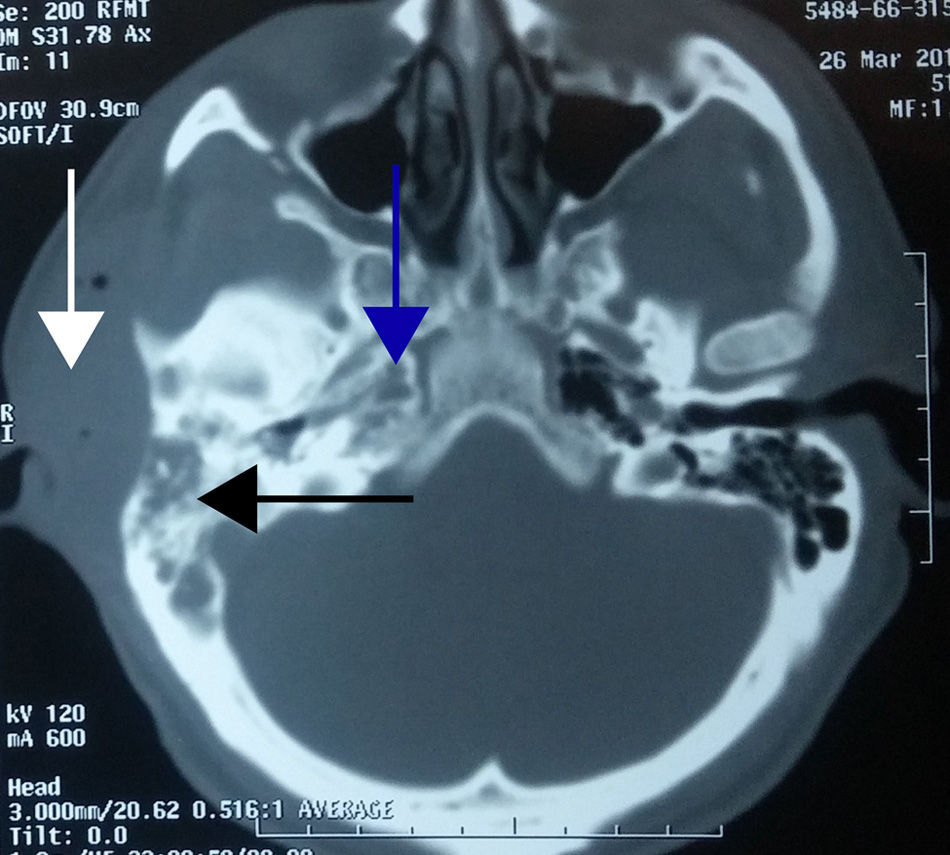

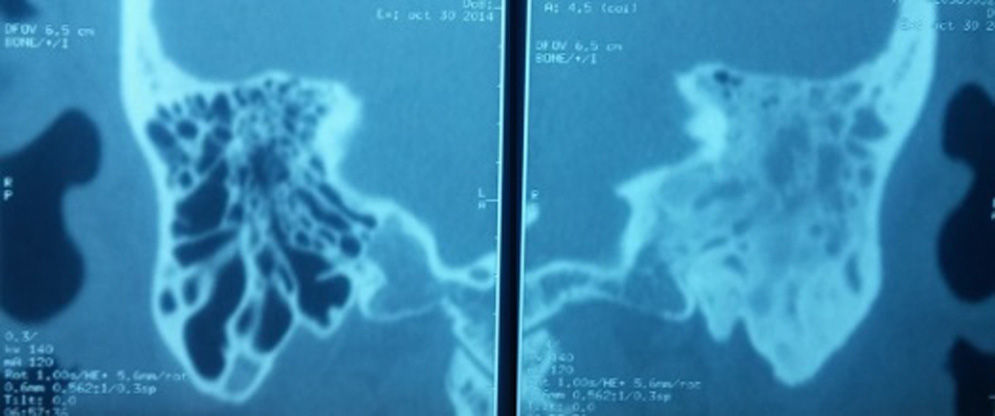

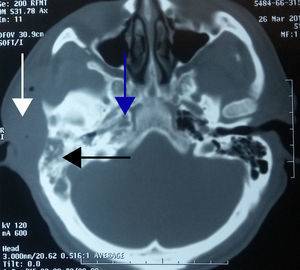

Case 3A 19-year-old male patient, referred to our department with alterations in gait, stupor, otalgia and headache; papilloedema on fundoscopy. CT scan of the ears showed left-sided otomastoiditis, while nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) of the skull showed a left sigmoid sinus thrombosis and cerebellar abscess. Therefore a simple mastoidectomy was performed, a ventilation tube placed and exploration of the sigmoid sinus undertaken, with drainage and evacuation of the abscess by posterior fossa craniectomy (Fig. 3).

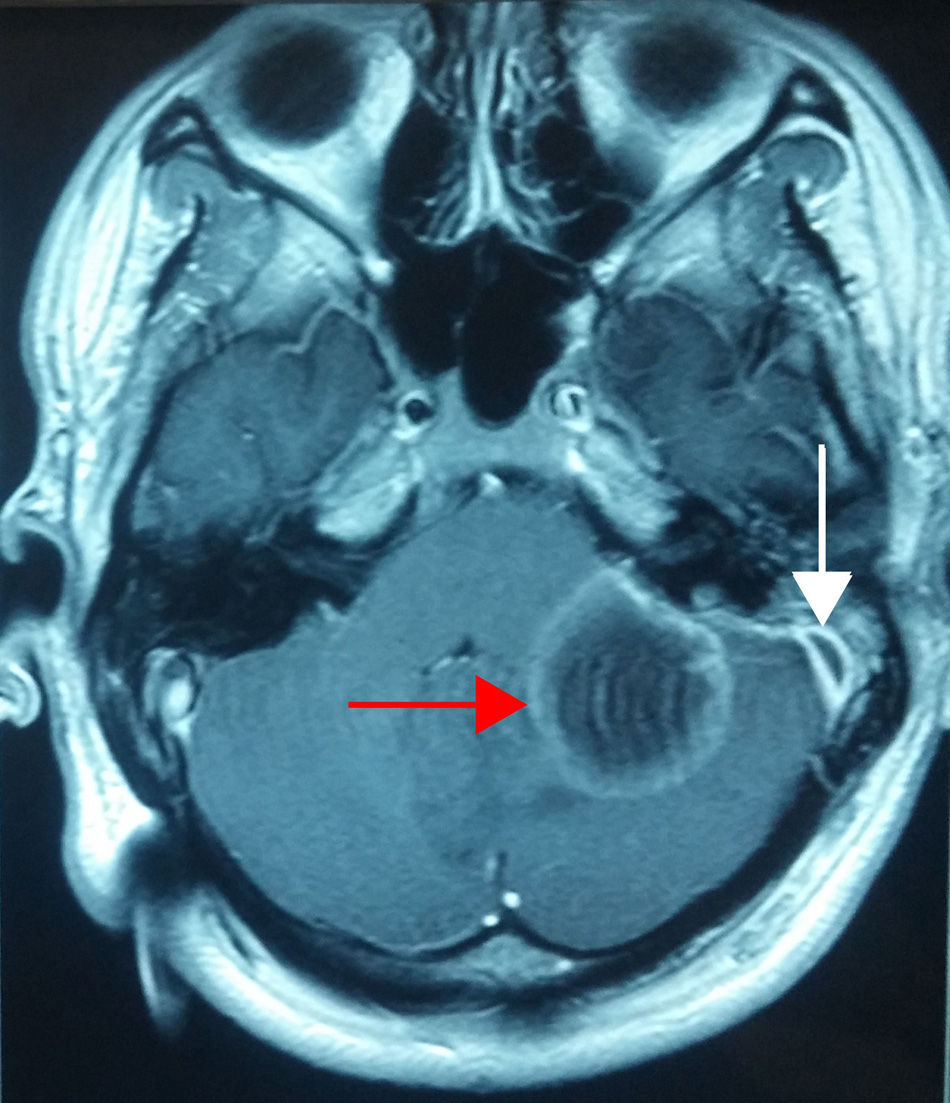

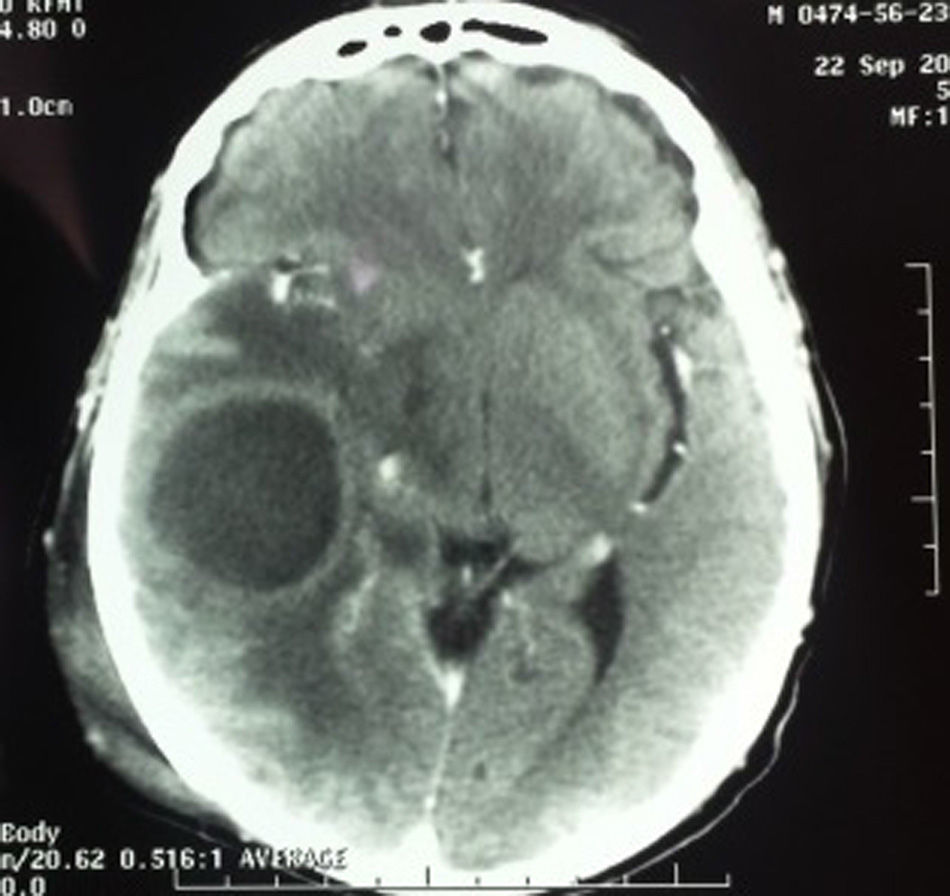

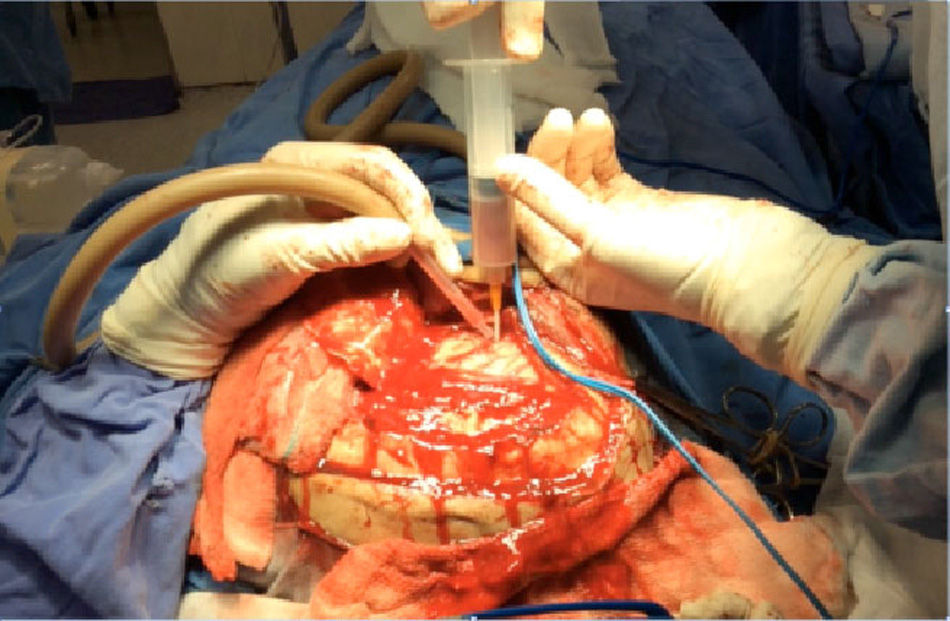

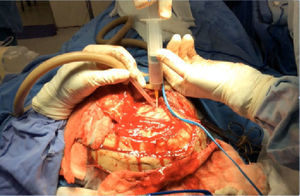

Case 4A 52-year-old man with a history of chronic kidney disease managed by peritoneal dialysis, referred to the department with a month-long history of right otorrhoea and increased volume in the ipsilateral retroauricular region, secondary to trauma 7 days previously. The CT scan revealed soft tissue oedema in the temporal region, otomastoiditis and a brain abscess in the temporal lobe (Fig. 4). The patient was treated by decompressive craniectomy, capsulectomy, drainage of the parenchymatous abscess, mastoidectomy with canal wall down and drainage of the retroauricular abscess (Fig. 5).

A 42-year-old male patient, diabetic, referred for assessment after presenting 3 symptoms of meningitis in the past month. The CT scan revealed a right-sided mastoiditis. Lumbar puncture reported turbid cerebrospinal fluid, with 6000 leukocytes/mm3 with 65% neutrophils, 332mg/dl protein, 107mg/dl glucose, culture negative; serum glucose of 279mg/dl, peripheral leukocytes 10,100μL (73% total neutrophils); polymerase chain reaction for tuberculosis, negative. The patient was treated with antibiotic therapy based on intravenous vancomycin and meropenem for 14 days and simple mastoidectomy (Fig. 6).

DiscussionAcute otitis media can be divided into 5 clinical stages that directly correlate with the clinical symptoms, and these can overlap: (1) Stage of tubotympanitis: causes discomfort, a feeling of fullness inside the ear, retracted tympanic membrane, and loss of luminous reflex; initially a serous discharge might be observed. (2) Hyperaemic stage: causes otalgia, general malaise and fever of up to 39°C, the tympanic membrane is congested and opaque. (3) Exudative stage: presents with intense otalgia, which can interrupt sleep, fever of over 39°C, marked hyperaemia of the tympanic membrane with loss of anatomical points of reference. (4) Suppurative stage: accompanied by a fever of 40°C or higher, and intense throbbing ear pain, tense tympanic membrane, with hyperaemic areas that are occasionally yellowish, denoting necrosis. (5) Stage 5: there can be spontaneous perforation of the membrane and otorrhoea over more than 2 weeks.4

The clinical course of acute otitis media is usually short, the infectious process is limited in most patients due to their immune system's response and the germ's sensitivity to the antibiotic used; however, a few patients can present complications (1–5%).

Acute mastoiditis is subdivided according to clinical stage into: (1) acute incipient mastoiditis, i.e., inflammation of the mastoid air cells, and (2) coalescent mastoiditis, which is when the inflammatory process destroys the bony trabeculae of the mastoids, resulting in an (organised) abscess.3 Acute mastoiditis can spread anatomically in 6 different directions: lateral, towards the soft tissues of the external ear; anterior, towards the external auditory canal; posterior, towards the sigmoid sinus or the posterior cranial fossa, causing thrombosis of the lateral sinus; medial, towards the labyrinth or the petrous apex, causing labyrinthitis, and/or apicitis; superior towards the middle cranial fossa, causing an epidural abscess; and inferomedial, towards the mastoid point, causing a Bezold abscess.4 The most common intracranial complication of acute mastoiditis is meningitis. Other intracranial complications include: subdural empyema, epidural empyema, intraparenchymal abscess, thrombosis of the transverse sinus, apicitis and otitic hydrocephalus. Extracranial complications are: peripheral facial paralysis, labyrinthine fistula, Bezold abscess, osteomyelitis and cervical fasciitis.5

The most commonly found germs in acute mastoiditis and its complications are: Streptococcus pneumoniae (S. pneumoniae), group A streptococcus, Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus), Haemophilus influenzae (H. influenzae) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa), pneumococcus being the most common in the general population.6,7 In 60% of our patients, 3 cases, no germ was isolated. Only 2 were isolated, one S. aureus and the other P. aeruginosa.

Otitis media complicated by Bezold abscess can occur in any age group, but more commonly in older children and adults, as in the former the pneumatisation of the mastoid extends towards the point, easily enabling perforation of the cortex. Adults affected by this complication usually have a history of chronic disease such as sinusitis or cholesteatoma. The most common germs in most cases are S. pneumoniae and pyogenes. Within the pathophysiology, once mastoiditis is found to be affecting the mastoid point, it causes it to erode with spread to the posterior triangle of the neck. Patients diagnosed with Bezold abscess typically present: gradual fever, otorrhoea, otalgia and hyperthermia in the neck with or without increased volume, over a period of days.

These abscesses are treated by mastoidectomy and drainage.8–10 In our case, the patient with Bezold abscess presented with atypical symptoms, they consulted with increased neck volume and an opaque tympanic membrane was found on physical examination. Initially, a diagnosis of deep abscess of the neck was considered. However, the imaging study revealed a purulent collection peripherally enhanced by the contrast medium, with a large proportion in the mastoid point, confirming the diagnosis of acute mastoiditis complicated by Bezold abscess. The developed and pneumatised mastoid with thinning of the cortex encouraged the formation of the Bezold abscess.

In case 2, the patient presented with a soft tissue abscess and petrositis secondary to the spread of the otitis media infection, the latter being a rare and late complication of purulent otitis media, with no history of otorrhoea with acute symptoms. The CT scan revealed the right mastoid had signs of disease therefore aggravated chronic otitis media was confirmed. With respect to petrositis, Gradenigo's syndrome develops when the inflammation spreads in Dorello's canal, which contains the sixth cranial nerve and the trigeminal ganglion. This is characterised by a trio of symptoms: external rectus palsy (sixth cranial nerve), retro-orbital pain (in the distribution of the fifth cranial nerve) and otorrhoea.4,10 In our case, purulent material was found in the ipsilateral petrous apex as well as the mastoid and the eardrum, with no orbital and/or trigeminal symptoms. The additional risk factor in this patient was chronic kidney failure.

In case 3, the complication presented in a patient with no significant ear history, with symptoms typical of acute otitis media complicated by thrombosis of the sigmoid sinus and hypertensive skull due to a cerebellar abscess. The latter present as the most common cause secondary to ear sepsis and they infect the cerebellum due to contiguity. It is suggested that cerebellar abscesses represent around 10–18.7% of intracranial abscesses. The proposed pathogenesis of this complication is the spread of the infection from small veins of the mastoid towards the sigmoid sinus, with subsequent propagation of inflammation through eroded or coalescent bone, causing an abscess around the longitudinal sinus and its thrombosis. Clinically it can present with fever, otorrhoea, retroauricular oedema, otalgia, headache, nausea, vomiting and meningeal signs. In these cases, treatment consists of mastoidectomy, exposure of the sigmoid sinus, exposure of the dura mater and puncture of the sigmoid sinus. If there is no perisinus abscess and the patient does not present symptoms of sepsis, coagulation of the sigmoid sinus should not be removed. If there is a perisinus abscess and signs of septicaemia, the sinus should be opened, the clot removed and the jugular vein ligated. In our case, no perisinus abscess was found, therefore the lateral sinus was not involved, it was punctured solely diagnostically.3,4,11

In case 4, the brain abscess was noteworthy in the patient with chronic kidney disease because it was an incidental finding. Clinically the patient had no symptoms of neurological involvement. Contrasted CT was performed to rule out a soft tissue abscess, because 7 days prior to the assessment the patient had suffered cranioencephalic trauma to that area when a ladder fell on him. The diagnosis of a brain abscess was confirmed by imaging studies. Within the pathophysiology of a brain abscess, the middle ear is of prime importance in the onset of intraparenchymal infection due to the frequency of otitis media and the possibility of it being difficult to control should it become chronic in the active phase. It is sometimes difficult to treat because the cavity of the middle ear is so closed and because its walls are in contact with pneumatised bone which encourages the progression and spread of germs to the intracranial compartments. When otitis is the predisposing factor it most frequently affects the temporal lobe or the cerebellum. Once a diagnosis has been made, emergency surgery is indicated to evacuate the pus collection and continuous flushing with antibiotic. It is important to remember the narrow space of the posterior fossa in which fast-growing masses rapidly cause a sudden loss of consciousness and the abscess to burst inside the fourth ventricle.3

In case 5, the patient presented with a history of diabetes diagnosed 12 years previously, with no history of ear disease. He had experienced 3 symptoms of meningitis in the past month, with cytochemical and cytological analysis of cerebrospinal fluid compatible with bacterial meningitis. With no history of temporal bone trauma, no labyrinthine fistula was encountered which would predispose the patient to recurrence of the neuroinfection. A viral panel was undertaken that was negative for human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B and C.

A complication must be suspected in acute otitis media of torpid evolution, when neurological signs appear within its pathophysiology. The infection can spread through bone erosion, the oval or round windows or due to retrograde phlebitis. Chronic otitis media causes meningitis more, which results in greater mortality; therefore it must be strictly monitored. In bacterial meningitis the microorganisms can fill the subarachnoid space through 3 routes: haematogenous, as a consequence of a contiguous focus of infection, secondary to otitis or pericranial fistula; retrograde propagation, a mechanism which sends a small infected thrombus through the emissary vein, when the infection is near the central nervous system, as in sinusitis, otitis or mastoiditis; and direct spread or spread due to contiguity, where the infection coming from nearby focuses of infection, such as orbital cellulitis, cranial osteomyelitis, soft tissue infections, paranasal sinuses, dermal sinuses or myelomeningoceles (congenital malformations which communicate with the outside) propagates. Another congenital route (preformed) has been described, especially in neonates and infants, due to the persistence of the petrosquamous suture.12 A diagnosis of meningitis is made from the clinical symptoms, lumbar puncture, a study which shows an elevated cell count in the cerebrospinal fluid. Because culture of cerebrospinal fluid requires time to confirm a diagnosis it is recommended that treatment is started immediately if the cytological profile in the cerebrospinal fluid suggests bacterial meningitis, which typically shows elevated pressure (200-500mmH2O), pleocytosis (1000–5000×106 cells/l white cells), with a predominance of neutrophils (≥80%), elevated protein (1–5g/l) and reduction in the proportion of glucose of the cerebrospinal fluid/serum (≤0.4).13 Antibiotic treatment of otogenic meningitis will depend on the causative germ and the antibiogram but generally, the administration of high doses of appropriate antimicrobials is recommended. In acute otitis media the associated germs are S. pneumoniae and type b H. influenzae, although the latter has practically disappeared in many countries since the generalised use of the conjugate polysaccharide vaccine. Intravenous treatment with third generation cephalosporins is recommended, the drug of choice being ceftriaxone, and tympanocentesis and myringotomy for culture and drainage. If infection by S. pneumoniae is confirmed, the use of intravenous vancomycin has been protocolised.12

ConclusionsImaging studies (CT and NMR) help in the diagnosis of the complications of otitis media. The use of antibiotics assists in the appropriate surgical treatment of the complications of otitis media, reducing morbidity and mortality in most patients who present with the disorder.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Acknowledgements go to Dr Katia Gámez Zermeño and the Neurosurgical Department for her participation in the management of ear and neurosurgery in 2 patients.

Please cite this article as: Govea-Camacho LH, Pérez-Ramírez R, Cornejo-Suárez A, Fierro-Rizo R, Jiménez-Sala CJ, Rosales-Orozco CS. Abordaje diagnóstico y terapéutico de las complicaciones de la otitis media en el adulto. Serie de casos y revisión de la literatura. Cir Cir. 2016;84:398–404.