Gunshot wounds in civilian population of México were quite rare. Currently, conflicts amongst organised crime groups are carried out with weapons, which are considered as exclusive use by the nation's army.

ObjectivesDescribe the experience of our institution and share results of clinical and radiological factors influencing the prognosis of the patients.

Materials and methodsObservational and retrospective study of patients with cranial gunshot wounds, which penetrated the duramater, treated from January 2009 to January 2013. We considered several demographic variables, Glasgow Coma Scale, upon admission, state of pupils, type of surgery and size of decompression, Glasgow Outcome Score upon discharge, and after 6 months.

ResultsOf 68 patients, we excluded those whose duramater was not penetrated, leaving 52 patients. The average age was 28.7 years, and 80.8% were males. All were surgically intervened, with 8% of general mortality. Mortality in the 3–5 points group was 43%, from the 6 to 8 points it was 6%, and no deaths in the 9–15 points. In patients with both pupils fixed, anisocoric and isocoric, mortality was 67%, 7%, and 3%, respectively. Bihemispheric, multilobar and unihemispheric trajectory of the bullet plus ventricular compromise was related to a Glasgow Outcome Score≤3 upon discharge in 90.9% of the cases.

ConclusionsGlasgow Coma Scale upon admission and state of the pupils are the most influential factors in the prognosis. Patients with a Glasgow Coma Scale>8<13 points upon admission, normal pupillary response, without ventricular compromise can benefit with early and aggressive surgical treatment.

Las heridas por proyectil de arma de fuego en población civil mexicana eran excepcionales. Actualmente los conflictos entre grupos de delincuencia organizada son con armas consideradas en México como de uso exclusivo del ejército.

ObjetivosDescribir nuestra experiencia y compartir el resultado de factores clínicos y radiológicos de influencia en el pronóstico de los pacientes.

Material y métodosEstudio observacional, retrospectivo de pacientes con herida craneal por proyectil de arma de fuego penetrando duramadre, tratados de enero de 2009 a enero de 2013, considerando variables: demográficas, escala de coma de Glasgow al ingreso, estado pupilar, tipo de operación y tamaño de descompresión, escala de resultados de Glasgow al egreso y a los 6 meses.

ResultadosDe 68 pacientes excluimos a aquellos en los que no hubo penetración de duramadre, quedando 52. Edad promedio de 28.7 años, hombres un 80.8%, todos intervenidos quirúrgicamente y con mortalidad general del 8%. La mortalidad del grupo con escala de coma de Glasgow de 3-5 fue del 43%, de 6-8 fue del 6%, y nula con 9-15. En los pacientes con ambas pupilas fijas, anisocóricas e isocóricas, la mortalidad fue del 67, 7 y 3%, respectivamente. Una trayectoria del proyectil bihemisférica, multilobar y unihemisférica más compromiso ventricular se relacionó con escala de resultados de Glasgow en el momento del egreso≤3 en el 90.9% de los casos.

ConclusionesEscala de coma de Glasgow al ingreso y estado pupilar son los factores con mayor influencia en el pronóstico. Pacientes con escala de coma de Glasgow>8 y<13 puntos al ingreso, respuesta pupilar normal y sin compromiso ventricular se pueden beneficiar con tratamiento quirúrgico agresivo temprano.

Wounds caused by firearm projectiles in the civil population in the city of Monterrey and its metropolitan area were considered exceptional, and most cases are related to suicide or armed robberies. Currently, conflicts among groups of organised crime involve weapons considered as for the exclusive use of the army in México, with victims being both women and men of all ages and with brain injuries where the kinematic of the trauma is greatly varied, from short distance “executions” to “stray bullets”, injuring people from a long distance (resulting in a greatly varied spectrum of altered states of consciousness upon admission of patients), to intracranial trajectory of the projectile injuring only superficial brain structures, where the type of surgical intervention that will be most beneficial for the patient becomes extremely relevant, since it has been proposed that depending on the aforementioned variables, patients may benefit from aggressive surgical treatment.1–4

In 2011, the city of Monterrey ranked 38 among the 50 most violent cities in the world, 12 of which overall are in México.5 For this reason, the purpose of our study is: to describe the experience of our neurological centre in the treatment of firearm projectile wounds in the cranium and share the result of the factors which contributed to the prognosis, as well as the decision-making regarding the neurosurgical approach based on clinical and imaging factors.

Materials and methodsWe carried out a retrospective observational study, consulting the clinical files of patients with cranial firearm projectile wounds admitted into the Neurological Surgery and Neurological Endovascular Therapy of University Hospital Dr José Eleuterio González, from 1 January 2009 to 31 January 2013. All patients were assessed within the first 30min after admission by the Emergency Department doctor and by a neurosurgeon, who performed a neurological examination following the guidelines of the Advanced Trauma Life Support protocol. Only patients with clinical or imaging data of penetration into the dura mater were included in our analysis. Demographical variables were analysed (age and gender), mortality, days in the intensive care unit (when required) and the general hospitalisation room, Glasgow Coma Score upon admission, pupils condition (equal, unequal or fixed), and if they had firearm projectile wounds in any other part of the body.

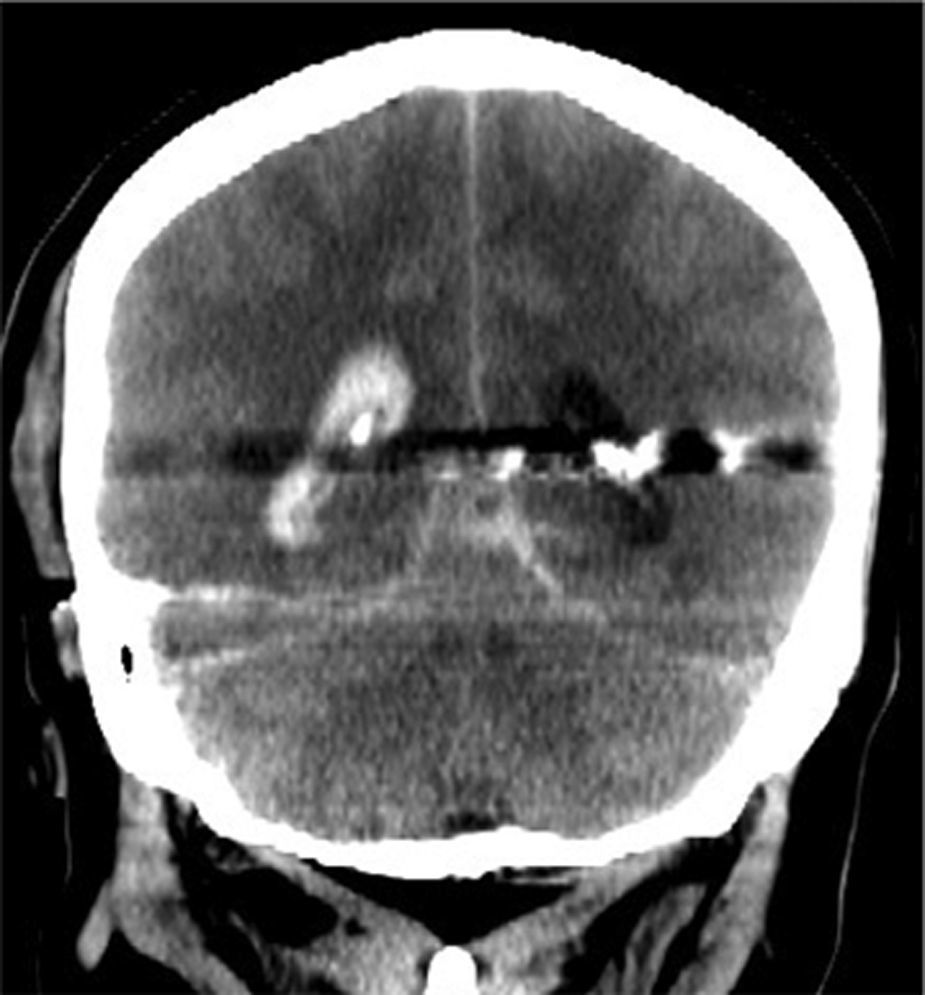

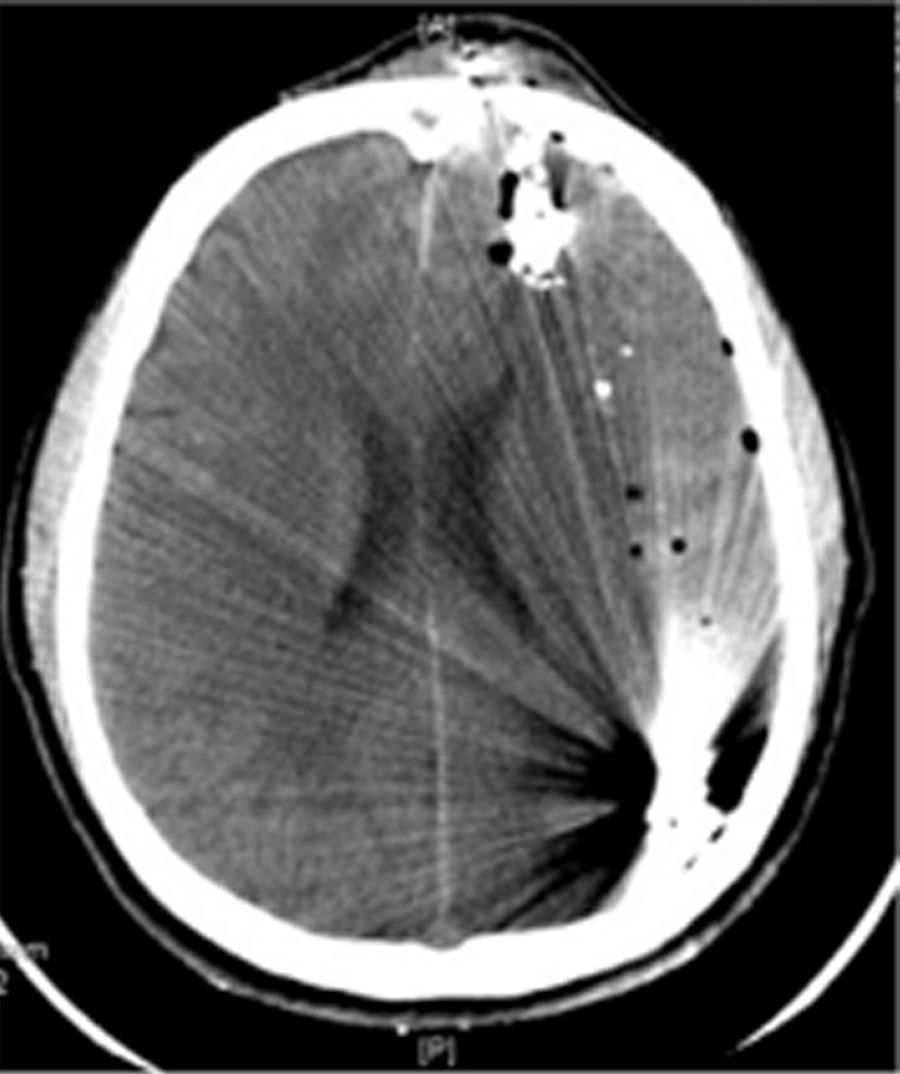

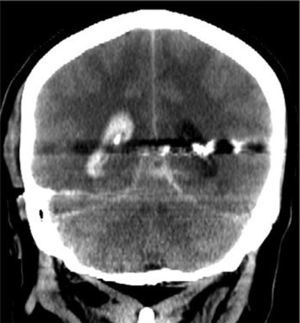

Cranial computed tomography studies upon admission and during the postoperative period were assessed. The trajectory of the projectile was described in the tomography, and then divided into 3 groups: bihemispheric (Fig. 1), hemispheric multilobar (Fig. 2), and unilobar (Fig. 3). It was also stated whether there was compromise of the ventricular function. In the computed tomography carried out in the postoperative period, the diameter of the surgery was measured, and then classified into 2 groups: surgical debridement and craniectomy, considering a bone removal of less or more than 5cm, respectively. Every debridement involved a duroplasty, and in craniectomies the dura mater was left open in a star shape at the discretion of the neurosurgeon performing the surgery.

All variables were related using the Glasgow Outcome Score upon dismissal and after 6 months, setting a score of 4 or 5 as a favourable result, and a score of 2 or 3 as an unfavourable result.

ResultsDuring the 4-year period of our review, 68 patients with cranial firearm projectile wounds were admitted, and 16 were excluded because the dura mater had not been penetrated. 52 patients remained, all of which were treated surgically. 80.8% were men and 19.2% were women. The average age was 28.7 years of age (range of 6 months to 62 years old), with the mainly affected age group being from 21 to 40 (52%). Thirty patients required admission into the intensive care unit with an average stay of 5 days (range of 2–29 days). The average of days of stay was 12.6 days (range of 2–45 days). Mortality was 8% overall.

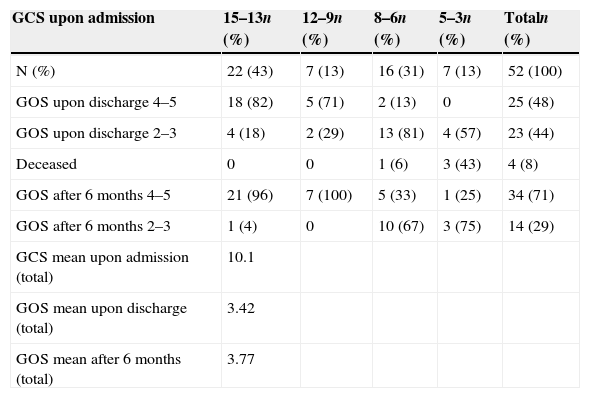

Glasgow Coma Scale upon admissionWe divided patients into 4 groups according to their results in the Glasgow Coma Scale upon admission (Table 1). The group with 15–13 points was the largest with 22 patients (43%), and also the one with the highest favourable Glasgow Outcome Score upon discharge (82%); but the group of 12–9 points was the one with the highest favourable score at 6 months (100%). Patients with 8–6 points represented the broadest group with unfavourable Glasgow Outcome Score upon discharge (81%), which decreased at 6 months (67%). The group with 5–3 points had the highest number of deaths (43%), with lower favourable Glasgow Outcome Score after 6 months (25%). No patient died during follow-up.

Comparison of GCS upon admission and its relation with the GOS upon discharge, at 6 months, and the average.

| GCS upon admission | 15–13n (%) | 12–9n (%) | 8–6n (%) | 5–3n (%) | Totaln (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | 22 (43) | 7 (13) | 16 (31) | 7 (13) | 52 (100) |

| GOS upon discharge 4–5 | 18 (82) | 5 (71) | 2 (13) | 0 | 25 (48) |

| GOS upon discharge 2–3 | 4 (18) | 2 (29) | 13 (81) | 4 (57) | 23 (44) |

| Deceased | 0 | 0 | 1 (6) | 3 (43) | 4 (8) |

| GOS after 6 months 4–5 | 21 (96) | 7 (100) | 5 (33) | 1 (25) | 34 (71) |

| GOS after 6 months 2–3 | 1 (4) | 0 | 10 (67) | 3 (75) | 14 (29) |

| GCS mean upon admission (total) | 10.1 | ||||

| GOS mean upon discharge (total) | 3.42 | ||||

| GOS mean after 6 months (total) | 3.77 |

GCS: Glasgow Coma Scale, GOS: Glasgow Outcome Score.

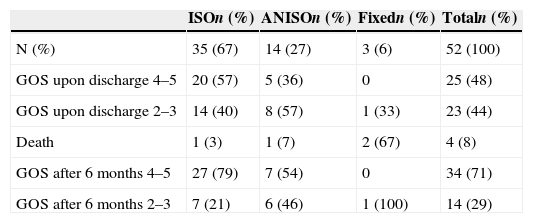

35 (67%) patients presented with equal pupils, the group with the highest favourable Glasgow Outcome Score upon discharge and after 6 months with 20 (57%) and 27 (79%) patients, respectively. When presented with fixed pupils, there was 67% mortality, which was lower in groups with equal pupils (3%) and unequal pupils (7%) (Table 2).

Condition of pupils upon admission and its relation with the GOS upon discharge and after 6 months.

| ISOn (%) | ANISOn (%) | Fixedn (%) | Totaln (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | 35 (67) | 14 (27) | 3 (6) | 52 (100) |

| GOS upon discharge 4–5 | 20 (57) | 5 (36) | 0 | 25 (48) |

| GOS upon discharge 2–3 | 14 (40) | 8 (57) | 1 (33) | 23 (44) |

| Death | 1 (3) | 1 (7) | 2 (67) | 4 (8) |

| GOS after 6 months 4–5 | 27 (79) | 7 (54) | 0 | 34 (71) |

| GOS after 6 months 2–3 | 7 (21) | 6 (46) | 1 (100) | 14 (29) |

ANISO: unequal pupils (anisocoria); GOS: Glasgow Outcome Score; ISO: equal pupils (isocoria).

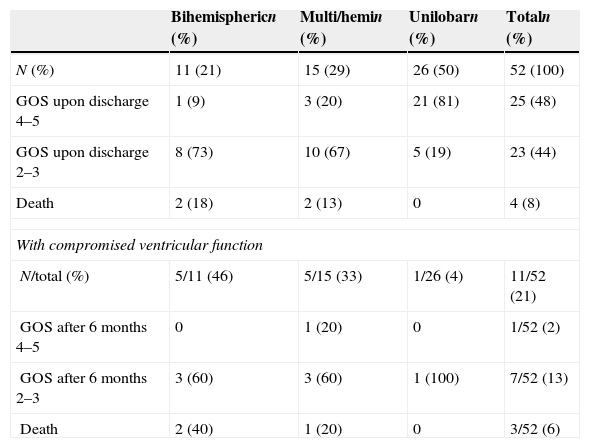

Half of the patients in our series presented injury in only one brain lobe, being the group with the highest favourable Glasgow Outcome Score upon discharge (81%). Deaths were only observed in the group with hemispheric multilobar and bihemispheric injury with 13% and 18%, respectively. In 11 patients the ventricular system was transgressed by the firearm projectile, with 64% discharged with unfavourable Glasgow Outcome Score and 27% mortality. Out of the 41 patients with no ventricular system injury, 40% had an unfavourable Glasgow Outcome Score upon discharge and mortality was 2% in that group (Table 3).

Trajectory of the projectile and compromised ventricular function and its relation with the GOS upon discharge.

| Bihemisphericn (%) | Multi/hemin (%) | Unilobarn (%) | Totaln (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | 11 (21) | 15 (29) | 26 (50) | 52 (100) |

| GOS upon discharge 4–5 | 1 (9) | 3 (20) | 21 (81) | 25 (48) |

| GOS upon discharge 2–3 | 8 (73) | 10 (67) | 5 (19) | 23 (44) |

| Death | 2 (18) | 2 (13) | 0 | 4 (8) |

| With compromised ventricular function | ||||

| N/total (%) | 5/11 (46) | 5/15 (33) | 1/26 (4) | 11/52 (21) |

| GOS after 6 months 4–5 | 0 | 1 (20) | 0 | 1/52 (2) |

| GOS after 6 months 2–3 | 3 (60) | 3 (60) | 1 (100) | 7/52 (13) |

| Death | 2 (40) | 1 (20) | 0 | 3/52 (6) |

GOS: Glasgow Outcome Score; Multi/hemi: multilobar hemispheric.

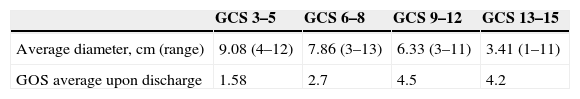

Surgical debridements were performed, with diameters within a range of 1–5cm in 30 (58%) patients and craniectomy in 22 (42%) with 6–13cm diameters. Relating the size of the craniectomy with the Glasgow Coma Scale upon admission, the largest amount of bone tissue was removed in the groups with lower scores without proof of beneficial effect in Glasgow Outcome Scores upon discharge. The group with Glasgow Coma Scale upon admission of 9–12 points with an average craniectomy diameter of 6.33cm was the group with the best Glasgow Outcome Score upon discharge with 4.5 on average (Table 4).

Average diameter of craniectomy/debridement related to GCS upon admission and its relation with the average of the GOS upon discharge.

| GCS 3–5 | GCS 6–8 | GCS 9–12 | GCS 13–15 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average diameter, cm (range) | 9.08 (4–12) | 7.86 (3–13) | 6.33 (3–11) | 3.41 (1–11) |

| GOS average upon discharge | 1.58 | 2.7 | 4.5 | 4.2 |

cm: centimetres; GCS: Glasgow Coma Scale, GOS: Glasgow Outcome Score.

A total of 17 patients (33%) had some kind of firearm projectile wound in another part of the body, with one diseased patient (6%), as compared with the 3 deaths (8.5%) in the group of the 35 patients with cranial wound only.

DiscussionPrognostic factors in patients with craniocerebral firearm projectile wounds have been studied broadly, mainly through retrospective studies both in civil population1–4,6–10 and battlefields. Especially the latter have served as a reference to establish the “Guidelines for the management of head trauma in the battlefield” issued by the Brain Trauma Foundation.11 As regards this specific type of brain injury in the civil population, the most important reference on prognostic factors are the “Guidelines for the management of patients with penetrating head injury”.12 It is surprising that said clinical guidelines establish differences among the surgical management for the civil and military population, based on the fact that there are ballistic differences, but conclude with a tendency towards “less aggressive” surgeries in both groups (a term we could conceptualise as local debridement of the wound, evacuation of haematomas and watertight dural closure). In our series of cases, most patients were injured during confrontations against the military or among criminal groups, with high-speed firearms. We note that the Glasgow Outcome Score upon discharge was poor and mortality was higher in patients with Glasgow Coma Scale<8 points, despite craniectomies with largest diameters over 5cm; but the group admitted with a Glasgow Coma Scale of 9–12 points had zero mortality and in cases where the Glasgow Outcome Score upon discharge was 4.5 on average with bone resections with an average diameter of 6.3cm (range of 3–11cm), hence we consider that in this group of patients the criterion of the neurosurgeon is important, since it takes into consideration a combination of factors, such as: the intracranial trajectory of the firearm projectile, as well as the evidence of subdural, intracerebral or epidural haematomas, with relevant mass effect despite an apparently “favourable” Glasgow Coma Scale upon admission. Furthermore, the analysis regarding the intracranial trajectory of the projectile is similar to that reported by different authors, who highlight the poor functional prognosis when the injury is bihemispheric1,7; and, if there is also compromise of the ventricular function, with a Glasgow Outcome Score upon discharge ≤3 in 91% of patients, compared to 41% when the ventricular system was not injured.

With regards to the Glasgow Coma Scale upon admission, it is confirmed that it is a key factor in the prognosis of the patient, related both with highest morbidity and mortality, when it is below 8 points1–3,7,12 the group of 3–5 despite the fact that on average broader craniectomies were performed, did not have a positive effect on the Glasgow Outcome Score upon discharge. In the group of 6–8, although only 12.5% was discharged with favourable Glasgow Outcome Score after 6 months of follow-up, it increased to 33% with an average craniectomy diameter of 7.9cm.

Regarding condition of pupils, Stone et al.9 reported that 4% of survivors have fixed pupils. Hofbauer et al.1 published mortality percentages ranging from 100% to 80%, which depended on whether the wound was self-inflicted or not with both pupils fixed. With unequal pupils, although mortality decreases to a higher or lower extent depending on the reported series, we all agree that the functional prognosis is poor even after 6 months of follow-up.

The average cost per patient treated for penetrating severe head trauma in a public institutions in Mexico, such as our hospital, was approximately $161,970 (Mexican pesos) upon discharge,13 without taking into consideration recovery expenses, which represent a potential public health problem, because the main group affected are men and women of 21–40 years of age (52% of our series of patients), and therefore it is an important factor to consider especially in patients with Glasgow upon admission of 3–5 because, as quoted by Levy et al. “it is the doctor who has the ethical responsibility to provide support as well as true and relevant information in all potential decision making scenarios”, because of the costs involved mainly for relatives and health systems.14

ConclusionFirearm projectile head wounds have become a frequent neurosurgical emergency in many cities in México, which has forced us to be familiarised not only with articles and clinical guidelines on penetrating head wounds in the civil population, but also with those published by the military authorities of various countries which have gone through times of war. There are multiple clinical, radiological and surgical factors which may influence the prognosis of a patient upon admission into a hospital's emergency room. The Glasgow Coma Scale upon admission, the condition of pupils and the site of the injury are the prognostic factors with the highest influence on the Glasgow Outcome Score upon discharge and after 6 months, and also on mortality. The size of the craniectomy/debridement and the presence of injuries in other parts of the body are not significant factors in the prognosis, except in the group of patients with a Glasgow Coma Scale of 9–12 points. A bihemispheric/multilobar projectile trajectory plus compromised ventricular function is a combination with a negative influence on the Glasgow Outcome Score upon discharge and after 6 months. We consider that patients with Glasgow Coma Scale > 8 and <13, with normal pupil response, without compromised ventricular function, benefit from early “aggressive” surgical treatment, and that for patients with Glasgow of 3–5 a decision must be made together with the family, due to the high mortality rate and the poor functional prognosis despite surgical treatment.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Martínez-Bustamante D, Pérez-Cárdenas S, Ortiz-Nieto JM, Toledo-Toledo R, Martínez-Ponce de León ÁR. Heridas craneales por proyectil de arma de fuego en población civil: análisis de la experiencia de un centro en Monterrey, México. Cir Cir. 2015; 83: 94–99.