The phenomenon of devolution, or transfer of human resource management (HRM) responsibilities to middle managers (MM) has mainly been studied and measured as a homogeneous and unidimensional phenomenon. However, the variations found in the literature suggest that this key HR concept may be of a heterogeneous and multidimensional nature. This inductive study explores whether devolution may be broken down into different dimensions, beyond the simple addition of transferred areas (selection, training, etc.). To do so, case studies are carried out in the hospital sector. The results identify the existence of four dimensions of HRM devolution to MM: task execution, decision making power, financial power and knowledge transfer. A number of propositions around these dimensions are presented. The recognition of the multidimensional nature of the concept and the different degrees of transfer, around which a set of propositions is presented, is intended to act as the basis for subsequently carrying out explanatory, predictive studies.

The current economic climate has forced organisations to once again question their own structures, with the resulting management decisions to cut back on management levels and employee numbers in certain areas, including, most notably, that of human resources. Some areas of people management have been outsourced (Valverde et al., 2011) or transferred to middle management (Cascon-Pereira et al., 2006) to create more streamlined human resource departments.

Although the topic of devolution of the HR function is well-developed research in the literature on human resource management, there are still many questions to answer regarding what devolution actually means. What is actually transferred—the implementation of staff management tasks or the decisions to be taken in this area? For example, the term devolution is used to refer indistinctly both to the responsibility for evaluating the performance of employees by middle managers and to the ability of these managers to make decisions as a result of this evaluation, despite the fact that these represent very different situations and responsibilities. Therefore, we need to specify certain nuances to be able to differentiate between such distinct types and degrees of the same phenomenon.

Likewise, the one-dimensional way of dealing with the concept has not allowed us to explore the mechanisms and diverse situations of devolution in terms of different contingent variables such as a company size or industry. Thus, we need to fully operationalise the concept so this phenomenon can be measured in future studies and then relate it to different contextual variables or internal, organisational variables.

In this context, the aim of this article is to explore the true nature of the role of middle managers in order to identify whether the devolution of human resource management (HRM) responsibilities to them is simple and homogeneous or whether, on the contrary, it occurs in different degrees or dimensions. This will be done with an inductive approach to the phenomenon to form the basis upon which to operationalise the concept and to carry out subsequent explanatory and predictive studies.

The devolution literature: explored and unexploredHRM devolution to middle managers has been defined as “the redistribution or transfer of personnel tasks or activities traditionally carried out by human resources specialists to middle managers” (Hoogendorn and Brewster, 1992:4; Brewster and Larsen, 1992:412; Hall and Torrington, 1998a:46). Probably because of its apparent clarity, this is a concept that has not received much academic discussion. Instead, it has received plenty of empirical attention, particularly at specific times usually linked to the economic cycle. For example, the current need to reduce costs and improve efficiency in HRM (Sheenan, 2012), and the interest for the link with the company's results (Azmi, 2010), have resulted in a renewed attention on devolution, although once again the specific nuances that this concept entails remain unchallenged. The popularity of studying devolution in sync with the economic cycle is easy to understand given that its main aim is to respond to competitive pressures from the environment by reducing hierarchical levels and restructuring an organisation (Armstrong, 1998; Storey, 1992; Beer et al., 1988). Although some place the advent of the human resource management (HRM) movement as a possible reason for the use devolution to middle managers (MM), Armstrong (1998) asserts that, while this approach has had a great influence on making more line managers responsible for personnel decisions and other key resources in the organisation, it cannot be regarded as the sole cause.

It is possible to distinguish between two types of studies about the devolution of HRM to middle managers. The first group of studies is descriptive and explanatory and focuses on determining what are the most frequently devolved areas of HRM and what are the consequences of this. The second group is mainly explanatory and it focuses on exploring the impact that devolution has on the role of the middle manager.

Within the first group of studies we can identify:

- 1.

General studies that explore which areas of HRM (recruitment and selection, training and development, etc.) are transferred and how they are distributed among the different members of the organisation and in particular among the HR department and middle managers (Merchant and Wilson, 1994; Hall and Torrington, 1998b; Armstrong, 1998; Valverde and Gorjup, 2005; Mesner Andolsek and Stebe, 2005; Maxwell and Watson, 2006; Valverde et al., 2006; Conway and Monks, 2010).

- 2.

Specific studies concentrating on devolution in a single area such as performance assessment (Redman, 2001), the administration of economic incentives (Currie and Procter, 1999), change management (McGuire et al., 2008) or other areas (Heraty and Morley, 1995; Bond and Wise, 2003; Fenton-O’Creevy, 2001; and others), and the consequences of such practices. These consequences have been evaluated in terms of quality in HR management (Renwick, 2003a; Thornhill and Saunders, 1998; Perry and Kulik, 2008), the achievement of organisational objectives, economic results and organisational efficiency (Renwick, 2003a; Azmi, 2010; Sheenan, 2012), the relationship between middle management and HR specialists (Currie and Procter, 2001), the effect on employees (Gilbert et al., 2011b) and the actual role of HR specialists (Renwick, 2003b; Hall and Torrington, 1998b; Currie and Procter, 1999; Budhwar, 2000; Renwick, 2000, and others).

In the second group of studies, which includes the perceptions of middle managers (Watson et al., 2006; Bondarouk et al., 2009; Brandl et al., 2009) and concentrates mainly on the impact of the HRM devolution to middle management, we can find identify:

- 1.

Studies highlighting how devolution has negative effects on middle managers by imposing changes such as increased workloads, a decline in the number of middle managers and their status, the need to deal with conflicting expectations, the loss of technical expertise, and diminished opportunities for promotion (Torrington and Weightman, 1987; Thomas and Dunkerley, 1999; Vouzas et al., 1997; Holden and Roberts, 2004).

- 2.

Studies highlighting the positive impact of this change in terms of greater autonomy and empowerment of middle managers within the organisation (Storey, 1992; Dopson and Stewart, 1990; Cunningham et al., 1996; Yusoff and Abdullah, 2008).

- 3.

More recent studies that provide mixed evidence regarding the effects of devolution on MM and question the usefulness of the debate on whether these effects are positive or negative because of the difficulty of making generalisations about it (Currie and Procter, 2005; McConville, 2006; Thornhill and Saunders, 1998; Renwick, 2003a; Mesner Andolsek and Stebe, 2005; Purcell and Hutchinson, 2007; Gilbert et al., 2011a). Although these studies recognise these difficulties and try to counter them by carrying out empirical studies in many different types of companies, they do not emphasise the possible contingent nature of devolution.

Despite the variety of studies that have been carried out about devolution, no attempt has been made to study whether this is a one-dimensional concept or if it materialises in various ways and to different degrees. The most common level of analysing HRM devolution consists of breaking the tasks down into different sub-areas of HRM (e.g., Brandl et al., 2009). Likewise, few studies have attempted to identify different degrees of devolution and those that have been carried out have been based on a simple aggregation of the number of tasks implemented by middle managers (e.g. Gilbert et al., 2011a). This lack of specificity results in the same name being applied to a great variety of situations, ranging from the simple devolution of specific tasks to the complete transfer of responsibility for managing people.

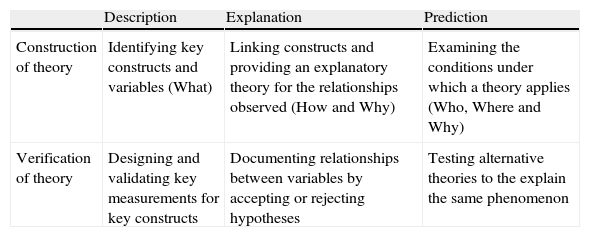

Snow and Thomas (1994, see Table 1) put forward a classification of field studies (used by Martin-Alcazar et al. (2008) to analyse the state of research in HRM) based on two dimensions: (1) the stage in the theory development (construction or validation) and (2) the aim of the theory (description, explanation or prediction). In the literature on HRM devolution to middle managers, a profusion of studies can be found in the following cells of the proposed matrix: 2 (Construction-Explanation), 3 (Construction-Prediction) and 5 (Validation-Explanation) (see Table 1), whereas there is a distinct lack of studies in cells 1 (Construction-Description) and 4 (Validation-Description). As Snow and Thomas (1994) suggest, inductive studies located in cells 1 and 4 of this matrix are needed to identify and define constructs such as the devolution of HRM. Such studies are needed in order to develop subsequent stages in any field of research. It seems, however, that in this area we have moved quickly on to research that would be classified in cells 2, 3 and 5 of the matrix without having looked into the definition and measurement of the concept to be studied (cells 1 and 4).

Summarised and adapted Snow and Thomas matrix (1994).

| Description | Explanation | Prediction | |

| Construction of theory | Identifying key constructs and variables (What) | Linking constructs and providing an explanatory theory for the relationships observed (How and Why) | Examining the conditions under which a theory applies (Who, Where and Why) |

| Verification of theory | Designing and validating key measurements for key constructs | Documenting relationships between variables by accepting or rejecting hypotheses | Testing alternative theories to the explain the same phenomenon |

The fact that there are still conceptual deficiencies regarding the devolution of HRM to middle managers means that exploratory studies are needed to better define the different nuances existing in each organisation. However, the approaches used in the literature have largely been quantitative (Brewster and Soderstrom, 1994; Poole and Jenkins, 1997; Budhwar and Sparrow, 1997; Budhwar, 2000), and therefore poorly suited to establishing the details of the existing heterogeneity. Furthermore, there is also a clear need to address this study from the perspective of middle managers, which has often been ignored in the literature.

Although most devolution studies treat it as a homogeneous process in which the only inter-organisational differences are in terms of the human resources areas that are devolved, some studies have identified the need to distinguish between the different elements or dimensions of what exactly is devolved. Nevertheless, this need has mostly been discussed at the end of these studies as suggested for further research rather than being used as a starting point or main focus of the studies themselves. Therefore, it is necessary to identify what dimensions these studies have proposed, even though they have not been tested, in order to guide our own exploratory study. For example, some prescriptive HR literature (Armstrong and Cooke, 1992; Armstrong, 1998) emphasises the importance of the degree of discretion in the transfer of HR responsibilities. Other authors have also written about the importance of other aspects akin to discretion. For example, Yusoff and Abdullah (2008) consider that devolution depends on the degree of empowerment or decision-making power that is granted to middle managers. Then there is the study by Kinnie (1990), who goes a step further by saying that devolution involves devolving authority to middle management, but that this authority necessarily implies the capacity to decide on financial matters. Similarly, McConville and Holden (1999) and Colling and Ferner (1992) comment that if budget responsibilities are not transferred along with staff responsibilities, then middle management have not been given true responsibility, but rather simply saddled with a burden.

Finally, other authors make emphasis aspects concerning knowledge. Specifically, Conway and Monks (2010) noted the problems arising from the fact that HR responsibilities were devolved to middle management but information systems and databases remained in the hands of the HR department. This suggests that if devolution of responsibilities is to be effective, middle managers should also be given access to the information they need in order to take these responsibilities on. In a similar, albeit more general, vein, Armstrong (1998) and Lowe (1992) pointed out that authority involves exercising personal influence based on knowledge. It follows that knowledge transfer and experience are required to effectively exercise the managers’ role. Although none of these authors attempts to directly explore the different degrees or dimensions of HRM devolution, their contributions as a whole suggest that it is a multidimensional phenomenon.

To sum up, the literature has traditionally regarded devolution of HRM as a unidimensional concept and so there has been no in-depth exploration of what is transferred, as seen from the perspective of those involved, particularly middle management. Therefore, this paper aims to explore the possible multidimensional nature of HRM devolution to middle managers and, as such, it qualifies for inclusion in cell 1 of Snow and Thomas's aforementioned model (1994).

MethodA qualitative methodology was regarded as the most appropriate for satisfying the exploratory and descriptive aims of this study (Patton, 1990). In particular, a case study (Yin, 2009) was used mainly because it aims to explore a contemporary phenomenon in depth and in its real context, and because it tackles a descriptive question: What does HRM devolution to middle management actually involve? (Yin, 2009; Cepeda Carrión, 2006).

SamplingIn line with the tenets of this methodology, theoretical sampling was carried out (Patton, 1990) to choose the sector, the organisations and the interviewees. Emphasis was placed on explanatory capacity rather than representativeness (Bonache, 1999) because the aim of this study was not to make statistics-based generalisations but rather to arrive at an in-depth understanding of the phenomenon. To do so, a context was sought in which the phenomenon to be studied was “transparently observable” (Eisenhardt, 1989). The devolution of HRM to middle managers is widespread and has been taking place for many years; therefore, it was decided to conduct the field work in a context where the phenomenon was relatively new and where the individuals affected could articulate their responses and reflections on it. In this regard the hospital sector in Spain seemed ideal because at the time of the field work it was undergoing the changes inspired by the logic of New Public Management (Ferlie et al., 1996) affecting most of the OCDE. Catalonia in particular, with its Parliament's approval of the LOSC (Health Care Organisation in Catalonia Act) in 1990, and the Basque Country were both pioneers in implementing New Public Management changes (Garcia-Armesto et al., 2010). Among other aspects, these health care reforms were characterised by the devolution of management functions to middle managers in order to improve efficiency in the provision of health care services. Furthermore, for the purposes of this study, it was expected that health care professionals with management responsibilities would be good informants/interviewees because such management tasks notably contrast with their chosen vocation and initial medical training, thus providing us with two good motives for choosing this sector.

On the basis of these considerations, two descriptive and exploratory case studies (hospital A and hospital B) were carried out, which make up the observation and analysis unit for studying the devolution of HRM to middle managers taking place in an organisation. The hospitals were chosen on the basis of intentional sampling whose criteria were obtained from the information provided by a prior pilot study consisting of in-depth interviews with key informants, namely, 3 members of CatSalut management in the Tarragona Health Region, 3 hospital directors, three experts who had written on the issue of health management, the President of the Official Association of Physicians of Barcelona (Colegio Oficial de Médicos de Barcelona), and 2 university professors who were experts in the field. These interviews provided the criteria for selecting the hospitals to be used in the study sample, including whether the hospitals were publicly or privately managed, whether members of the ICS (the Catalan Institute of Health), members of the XHUP (the Catalan Public Health Network) or university hospitals. These pilot interviews also provided the criteria for selecting the interviewees/respondents (type of service; professional group; promotion criteria), although as with all qualitative research, the analysis of the data generated new selection criteria regarding the respondents (seniority (years) within the post; size of the service, etc.). Thus, we chose hospital A because it was implementing a new formula for improving management in that it was a hybrid organisation, publicly owned but privately managed. The idea behind this choice was that the hospital's characteristics would probably show a higher degree of devolution of HRM to middle managers. The analysis of the data collected in hospital A provided the criteria for the selection of hospital B, a hospital owned and managed publicly. That is, the aim was that the two organisations should be as different as possible, thus enabling the use of maximum variation sampling (Patton, 1990:172).

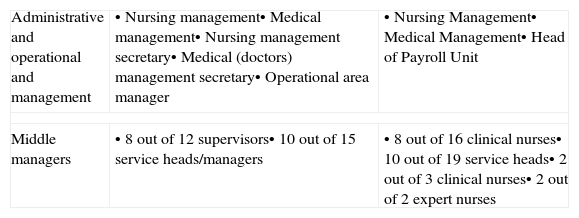

As for the selection of interviewees, the obvious choice was to gather information from the middle managers themselves given that the aim of the study was to gain more knowledge about HRM devolution to middle managers. Every attempt was made to ensure the utmost diversity of the theoretical sample of middle managers. Thus the selection criteria took into account the informants’ professional group (doctors and nurses), type of service (care provider or not, and within the former: surgical and non-surgical), age, gender, time spent in middle management, reason for promotion or selection, prior training in management, and the number of staff they were responsible for. In order to contrast perspectives and to improve internal validity, interviews were also conducted with managers, directors and specialists in personnel management, resulting in the final sample shown in Table 2. The final number of interviews was determined by the theoretical saturation point (Lincoln and Guba, 1985:202) and by the time and resources available.

Final sample.

| Administrative and operational and management | • Nursing management• Medical management• Nursing management secretary• Medical (doctors) management secretary• Operational area manager | • Nursing Management• Medical Management• Head of Payroll Unit |

| Middle managers | • 8 out of 12 supervisors• 10 out of 15 service heads/managers | • 8 out of 16 clinical nurses• 10 out of 19 service heads• 2 out of 3 clinical nurses• 2 out of 2 expert nurses |

No further details on the sample are given in order to protect the anonymity of the respondents. The sample represented 73% of the management staff at both hospitals and ensured a high level of diversity.

Data gathering and analysisThe primary method of collecting data was to conduct in-depth interviews of between 2 and 4h (in most cases spread over several sessions). The interviews were recorded and transcribed in full. The interview questions were gradually adapted to reflect the emergence of themes directly related to the object of study.

The information from the interviews was accompanied by participant observation, as a supplementary method recommended by Patton (1990:245). Permission was obtained to follow middle managers in their daily work, and the hospital was visited almost daily during the 10 months of fieldwork. In addition, internal documents (job descriptions, organisational structure, performance evaluations, etc.) and external documents (brochures, press releases, information from the internet etc.) were also gathered. The data obtained by these methods were analysed using an iterative method that alternated the data gathered on the basis of the analysis criteria with a subsequent analysis that aimed to collect new data to confirm or refute the emerging theoretical structure (Miles and Huberman, 1994; Strauss and Corbin, 1998). The NVivo qualitative analysis software was used to manage the large volume of data gathered. Data were collected and analysed until a saturation point was reached (Miles and Huberman, 1994) whereby new data gathered no longer contributed substantially to a greater understanding of the phenomenon under study.

RigourSteps were taken to ensure this study's reliability and validity. In order to improve the validity of the study and ensure that information was obtained from the appropriate individuals, the following steps, based on Glaser and Strauss (1967), were taken:

- •

Middle managers were identified on the basis of the answers that the hospital members gave to the following question: Who would you define as middle managers?

- •

The middle managers’ perspective was adopted by using their own terminology to better understand their perceptions.

- •

Different data sources (top management, documentation and middle management) and different data-gathering methods (in-depth interviews and participant observation) were used to triangulate the data and methodology respectively (Denzin, 1978; Cabrera Suárez and García Falcón, 2000).

- •

The preliminary results of the study were presented and discussed with the members of the hospitals at a hospital management workshop organised by the university.

Furthermore, in order to ensure internal validity, we followed the constant comparative analysis method proposed by Glaser and Strauss (1967), where disconfirmation of the emerging ideas is used in the other organisation chosen through theoretical sampling. Finally, we achieved reliability by ensuring the transparency of the whole analysis process. This involved writing memos regarding the inferences made throughout the analysis, recording all the steps taken in the research process and creating an audit trail (Lincoln and Guba, 1985; Cutcliffe and McKenna, 2004) in which we recorded the protocols used to conduct the case studies, such as the information we needed to obtain before entering each hospital, the order of the interviews (for example, we found that once we gained access to the hospitals it was important to interview the health care staff before interviewing the management), the changes made in the interview script due to the iterations between data gathering and analysis, etc.

Exploration of HRM devolution to middle managersIn this section, we show the results of the analysis of human resources management devolution at both hospitals studied. First, we describe the general human resource function at each hospital. Then we go on to identify the different ways in which devolution occurred.

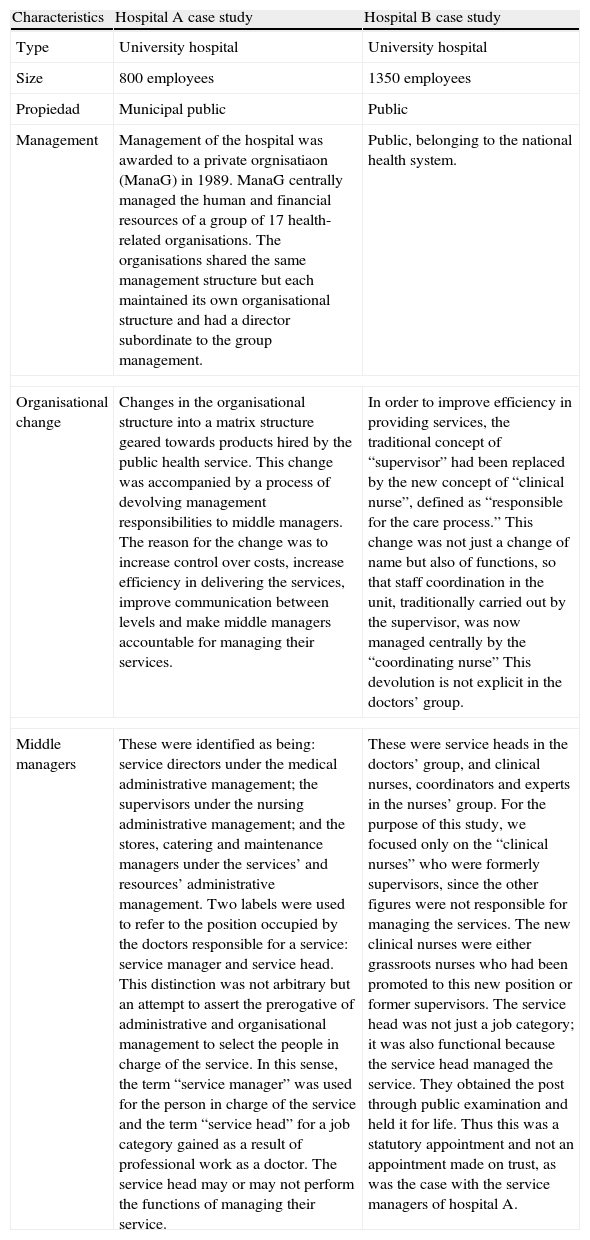

The human resource function in the case studiesTable 3 details the most important characteristics of each hospital in terms of the topic of study. Comparatively, at hospital B the nurses enjoyed greater independence from the doctors than was the case at hospital A, as hospital B was not managed by doctors. Hospital B had not undertaken a formal devolution process, and thus, doctor managers at hospital B had obtained their positions through promotion rather than having been formally appointed as middle managers with devolved HRM responsibilities. This meant that not all of them equally recognised the management responsibilities associated with their posts. Another distinguishing feature was the greater centralisation of management power at hospital A than at hospital B.

Distinguishing characteristics of the case studies.

| Characteristics | Hospital A case study | Hospital B case study |

| Type | University hospital | University hospital |

| Size | 800 employees | 1350 employees |

| Propiedad | Municipal public | Public |

| Management | Management of the hospital was awarded to a private orgnisatiaon (ManaG) in 1989. ManaG centrally managed the human and financial resources of a group of 17 health-related organisations. The organisations shared the same management structure but each maintained its own organisational structure and had a director subordinate to the group management. | Public, belonging to the national health system. |

| Organisational change | Changes in the organisational structure into a matrix structure geared towards products hired by the public health service. This change was accompanied by a process of devolving management responsibilities to middle managers. The reason for the change was to increase control over costs, increase efficiency in delivering the services, improve communication between levels and make middle managers accountable for managing their services. | In order to improve efficiency in providing services, the traditional concept of “supervisor” had been replaced by the new concept of “clinical nurse”, defined as “responsible for the care process.” This change was not just a change of name but also of functions, so that staff coordination in the unit, traditionally carried out by the supervisor, was now managed centrally by the “coordinating nurse” This devolution is not explicit in the doctors’ group. |

| Middle managers | These were identified as being: service directors under the medical administrative management; the supervisors under the nursing administrative management; and the stores, catering and maintenance managers under the services’ and resources’ administrative management. Two labels were used to refer to the position occupied by the doctors responsible for a service: service manager and service head. This distinction was not arbitrary but an attempt to assert the prerogative of administrative and organisational management to select the people in charge of the service. In this sense, the term “service manager” was used for the person in charge of the service and the term “service head” for a job category gained as a result of professional work as a doctor. The service head may or may not perform the functions of managing their service. | These were service heads in the doctors’ group, and clinical nurses, coordinators and experts in the nurses’ group. For the purpose of this study, we focused only on the “clinical nurses” who were formerly supervisors, since the other figures were not responsible for managing the services. The new clinical nurses were either grassroots nurses who had been promoted to this new position or former supervisors. The service head was not just a job category; it was also functional because the service head managed the service. They obtained the post through public examination and held it for life. Thus this was a statutory appointment and not an appointment made on trust, as was the case with the service managers of hospital A. |

At hospital A, strategic human resources management was the sole responsibility of the operations manager from ManaG (the private organisation responsible for managing the hospital). This manager decided the human resources strategy and policies for the entire group (training, remuneration, performance assessment, etc.). At hospital B, strategic human resources management was also centralised in the top management, especially regarding decisions with financial implications. However, top management had less decision-making power than at hospital A because it was restricted by the overarching strategies of the public institutions to which the hospital belonged.

At the operational level, doctors and nursing managers of both hospitals implemented the HR strategy and policies put forward by top management (and, in the case of hospital B, by the public institution to which it belonged). Furthermore, ManaG's direction of labour relations played a purely administrative role at hospital A (Tyson and Fell, 1986). Its main functions were to oversee contracts, sick leave, the payroll, etc., but it had no power to decide on matters relating to hospital staff and acted purely as an internal administrative agency. Moreover, training officers simply administered and coordinated training for the entire group, whereas actual training needs were identified by the middle managers, who made final decisions about training, with the operational area manager. Likewise, the human resources managers at hospital B also had a purely administrative role. Consequently, both hospitals turned to outside consultants regarding specific matters such as job descriptions and competency management.

Identification of dimensions in the devolution of HRM to middle managersOur review of the literature indicated that the devolution of HRM to middle managers would most likely be multidimensional, and this indeed turned out to be the case when our study identified the four following dimensions:

- •

Implementation of tasks, such as the different areas of human resources transferred.

- •

Decision-making power, that is, the ability to decide on the material and human resources that are managed.

- •

Financial power, that is, having the necessary budget to manage human and material resources.

- •

Knowledge, that is, the information and training needed to carry out the responsibilities devolved.

In hospital A, clinical procedure management, patient management, coordination and organisation of the unit's human and material resources, and budgetary control had been explicitly devolved to middle managers, and this was stated in the new job descriptions. Depending on the professional profile of middle management and their willingness to take on responsibilities, other tasks such as monitoring waiting lists were also transferred. At this point it is important to note that devolution includes specific HR tasks (e.g., evaluating team performances) and other areas of management (for example, monitoring waiting lists).

In hospital B, two different realities coexisted, one for nurses, to whom management tasks had been formally devolved; and another for the doctors, to whom such tasks had not been formally devolved, but who were implicitly considered responsible for managing human and material resources. Therefore, at both hospitals and for both doctors and nurses, the execution of HRM tasks had been devolved.

Devolution of decision-making powerThe devolution of decision-making was clearly distinguished by the MM from the previous kind of devolution in that it was referred to as “deciding”, whereas task devolution was considered as “doing”. This dimension of decision-making devolution was identified and explored in different areas of human resource management at both hospitals. In recruitment and selection, doctors had different decision-making powers from nurses. Nurses at both hospitals had less decision-making power because their job profiles were less specialised than those of the doctors. This meant that nursing recruitment was controlled from higher up the chain of command. At hospital A, once the decision to increase staff numbers had been approved by the medical administration and management, doctors had complete power over the selection of candidates. At hospital B, doctors had less decision-making power because, in addition to the budget constraints present at hospital A, they were also restricted by the public services’ selection system. Thus, at hospital B, doctors’ expert opinion carried significant weight but was not totally decisive because the final outcome also depended on the decisions made by other members of the selection panel. In the case of the nurses, the opposite occurred: hospital B's clinical nurses had greater decision-making power than did the supervisory nurses in hospital A, where the selection of nursing staff was carried out centrally by ManaG. The supervisory nurses could only communicate their candidate preferences, but these preferences were not always taken into account. They had even less power to decide on whether to increase staff numbers. Instead, in hospital B, clinical nurses participated in decision-making with the human resources assistant or the nursing management once top management had approved the decision to take on new staff.

As mentioned in the previous section, both doctor and nurse MMs were fully responsible for carrying out performance assessments. However, they had no power to take either positive or negative action based on the results of these performance assessments, with the result that they regarded performance appraisal as pointless and consequently did not heavily involve themselves in it.

In training and development, there was no difference between hospitals but there was between the two groups of professionals. Middle managers identified training needs, and using these they drew up proposals for the medical and nursing management. Whether these needs were met or not depended on the budget. Doctors received additional funding from the pharmaceutical industry to attend courses and conferences. They also had greater power to organise their healthcare responsibilities and shifts so they could attend courses. Also, because doctors are more specialised than nurses, they were able to decide on the type of training they required and who would deliver it. For the nurses, however, it was the nursing management and top management who selected the trainers and courses centrally. Moreover, they had no additional source of funding for training, which meant that they relied exclusively on the hospital's budget. To overcome this limitation, the supervising and clinical nurses acted directly as trainers and organised the nurses’ calendars and schedules to so that most of them could attend the courses organised by the hospital.

As for dismissals, middle managers had no decision-making power whatsoever over permanent staff. Their only option was to arrange a transfer or voluntary resignation. In this sense, nurses had a greater say than doctors because more transfer possibilities were open to them on account of their lower level of specialisation. Regarding temporary staff, they were able to recommend whether their contracts should be renewed or not.

Middle managers had no decision-making power regarding compensation. At both hospitals a fixed salary was set by collective agreement. Because middle managers lacked any power to offer individual financial incentives, they used other instruments to reward their staff and to overcome the perceived lack of autonomy in the management of their personnel, including verbal recognition, career development and the organisation of schedules and holidays. Additionally, doctor managers also used training and attendance at conferences as incentives.

In communication, middle managers did have decision-making power. Their role as intermediaries between management and staff meant that they had to take decisions about what they would say, which resulted in them often acting as a filter. In health and safety, their only role was to control compliance with risk prevention standards and to follow protocols. For team management, motivation and leadership, they reflected that they did not have enough time or autonomy to carry them out successfully. Instead, middle managers had the power to decide on the distribution of tasks and organisation of schedules, which they used as incentives for their team members. In hospital B they had less say in these matters due to more stringent collective agreements and public sector attitudes and culture.

To sum up, it can be seen that there was significant devolution from human resources to middle managers in terms of the simple implementation of tasks, but not in terms of decision making power to be used as a veritable management tool. In the cases where they did have decision making power (distribution of tasks, organisation of schedules and training), this was used to incentivize their staff. There were differences between doctors and nurses, with the latter having less say.

Devolution of financial powerMiddle managers in the hospitals analysed were not able to decide on the budget for their services, and they recognised this was a separate issue, one that they placed beyond decision-making power. Their participation in economic management was limited to budgetary control and informing the management of the service's needs. Budgetary management at each hospital was concentrated in the hands of top management, who together with the managers of each centre decided on the budgetary allocations for each service.

Middle managers clearly regarded this way of operating as negative. They felt that the priorities identified by their respective units should define the allocated budget instead of receiving a set budget and having to decide how to act based on this. They also complained that a lack of information regarding the costs incurred by the service meant that they were unable to control their budgets efficiently. Also, their budgets were subject to variations in healthcare provision over which they had no control, which led to them becoming demotivated as they failed to comply with the economic objectives set for them by top management every year. The nurses had even less financial power than doctors because the budget was allocated to the department as a whole and was distributed by the director or head of service. The lack of financial power drastically limited the autonomy of middle managers when it came to managing their teams and in particular to motivating them through financial incentives or training. This led to feelings of frustration and helplessness, which they saw as the main difficulty of their job. In this sense, they considered financial power as the cornerstone of autonomy needed to carry out their jobs.

Devolution of knowledgeOne last dimension, generically referred to as knowledge transfer, was identified. This encompasses the knowledge needed by middle managers to carry out devolved responsibilities whether in order to implement tasks, take decisions or manage budgets. Although the matter of knowledge transfer appeared in almost every interview, unlike the previous three dimensions it has different properties and characteristics that make it a less specifically defined dimension. In any case, devolution in this dimension tended to involve either information for decision-making or the training of the middle managers themselves.

In terms of training, there was less devolution for middle managers at hospital B. In hospital A, we found that there had been some training programmes about management in the past with the aim of transferring to them the knowledge and experience necessary to manage their units and staff. Also, if middle managers wished to take a master's degree in healthcare management outside the hospital they could ask for a subsidy to cover part of the cost. Despite these initiatives and the desire expressed by the middle managers to acquire management knowledge, they were unable to do so because their workload prevented them from being trained outside the hospital. Furthermore, a lack of funds had meant that the hospital had not directly organised any management training for several years, and so middle managers depended on their own initiative if they wanted to receive any training. Consequently, only some knowledge transfer in the form of training had occurred at hospital A and it was at an absolute minimum at hospital B.

In terms of information for decision-making, devolution was also low at both hospitals: In hospital B this was due to a lack of access to this information, perhaps because, as a public institution, there were greater levels of bureaucracy. Hospital A had access to some information, but this was of little operational use in their units since it had been designed with top and HR in mind rather than with the idea of being a management tool for the middle managers.

Discussion: relationship between dimensions and degree of devolutionThe analysis of the empirical study has clearly shown that devolution materialises in a wide range of aspects of transferred HR responsibilities. Moreover, these aspects have been grouped into different dimensions, namely: devolution of tasks, decision-making power, budgeting (financial power) and knowledge. Although these dimensions had not been studied directly, some authors had suggested that they would be a useful approach to adopt in order not to treat devolution as a simple transfer of task execution. For example, both Armstrong (1998) and Yusoff and Abdullah (2008) highlight the importance of devolving not only task implementation but also any decision-making that may arise from it (for example, devolving not merely the writing of performance evaluation reports, but also having the power to decide what to do with employees with unsatisfactory reports). Furthermore, McConville and Holden (1999) emphasise the difference between implementing human resources tasks and having a budget to manage them. Likewise Conway and Monks (2010) warn of the significant barriers to efficiency when tasks are transferred to middle managers, but the HR department still retains the knowledge and information about their teams.

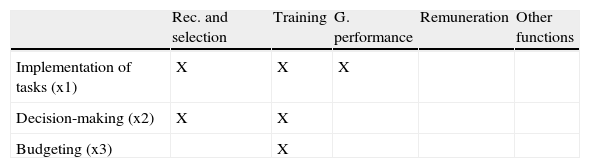

Relationship between dimensionsBeyond identifying the dimensions of the devolution, and perhaps even more important, is the fact that these dimensions do not appear to be independent from each other, but in the cases examined they materialise in an orderly and cumulative way. For example, we have seen evidence of transfer of tasks alone and of transfer of both tasks and decision-making, but not for the transfer of decision-making power without the tasks. Similarly, albeit in only a few cases, we observed devolution of financial power, but never without the tasks and decision-making being devolved beforehand. This interesting finding not only helps us to better understand the nature of HRM devolution to middle managers, but it also allows us to propose an approach to operationalising the degree of devolution, which in previous studies has almost always consisted of simply adding up the number of functional areas devolved (e.g. Gilbert et al., 2011a). This proposal for measuring the degree of devolution involves taking into account not only the number of functional tasks transferred (selection, training, etc.), but also the dimensions in which each of these functions has been transferred. Also, it involves giving greater weight to each subsequent dimension (less for task devolution, more for decision-making, and even more for financial power). An example of this approach is shown in Table 4, where different degrees of devolution are illustrated in two hypothetical organisations. Here, the degree of devolution ranges from a minimum degree, where only a few areas are transferred, and only with regards to task execution, to a maximum, where for a large number of tasks not only the implementation but also the decision-making and the budget are devolved.

Example of proposal for operationalization of HRM devolution to middle managers. Although the middle managers are involved in a greater number of HR functions, the organisation of the upper part is considered to have less degree of devolution than the organisation of the lower part, since the decision-making and financial power have greater weight.

| Rec. and selection | Training | G. performance | Remuneration | Other functions | |

| Implementation of tasks (x1) | X | X | X | ||

| Decision-making (x2) | X | X | |||

| Budgeting (x3) | X |

As it can be seen from the example, our proposal for operationalization does not include the dimension of knowledge transfer. As regards this point, we have tried to err on the side of caution because (1) the aspects included in this dimension are highly diverse (as discussed above, it includes aspects that may even be considered to be two separate dimensions, such as information and training); and (2) the analysis has not been able to clearly determine whether this dimension actually forms part of HRM devolution to the middle managers, whether it is a prerequisite for the devolution to take place, or whether it is a multiplier of its efficiency. Therefore, we suggest that future studies determine the precise role of knowledge transfer in the operationalization of HRM devolution to middle managers.

Degree of devolution in the hospitals analysedThe gradation of HRM devolution proposed in this study should become fully useful and applicable once it has been validated through quantitative studies. However, even at this point in its development, it is already useful in order to appreciate the degree of devolution in the hospitals analysed. Thus, at hospital A it shows a medium degree of devolution to doctor managers, involving some aspects of tasks execution, decision-making power and knowledge in some areas, whereas for nurses there was only a minimum degree of devolution of management responsibilities and tasks and very limited transfer of decision-making power. At hospital B, for doctors there is a minimal degree of devolution limited to task execution, and two different degrees of devolution for nurses depending on whether or not they had been supervisory nurses before becoming clinical nurses.

Regarding the reasons for the different degrees of devolution in both cases, hospital B's lesser degree of devolution can be attributed to the fact that it was a public sector institution with more limits to decision making power. Regarding the differences identified between the two professional groups studied, the supervisory/clinical nurses’ power of decision was restricted by the manager/head of the service and because nurses had a lower level of specialisation, which meant that certain decisions were taken at higher levels. In this sense, the more a decision required technical knowledge (e.g. as regards materials, drugs, selecting a specialist, selecting a trainer, etc.), the more likely it was to be devolved to those who had such knowledge.

ConclusionsThis section describes the conclusions that can be drawn from the present study's results and the implications that these have for organisational practice. It also describes the contributions that the study makes to the literature.

Regarding implications, the case studies show that the overall degree of devolution is actually quite low. Indeed, although a number of responsibilities are devolved to both nurse and doctor middle managers, they are unable to carry out these tasks effectively because other dimensions (decision-making power, financial power and expert power) are not devolved to them. Thus, one can talk of devolution in terms of task implementation but not in terms of the autonomy to carry these tasks out. Autonomy in its full sense is conceived by the middle managers in this study as the financial power to take decisions about the distribution of budgets and other resources. Thus, devolution of management responsibilities without devolution of the decision-making and financial powers, far from leading to a sense of empowerment as proposed by some of the literature, leads middle managers to feelings of stress because they are unable to fully carry out the responsibilities devolved to them. This finding confirms the need identified at the beginning of this study about considering devolution as a multidimensional phenomenon in order to better understand its many manifestations within an organisation. Furthermore, the operationalization of devolution into different dimensions undertaken in this study has proven to be suitable for distinguishing the different degrees and typologies of devolution.

Another important finding of this study is the fact that middle managers do not differentiate between the devolution of HRM tasks and the devolution of other management tasks, so to them, the label “devolution” includes all management functions. This result suggests that the different aspects of management are inseparable at these levels, as shown by the fact that people management is a crucial tool for carrying out other aspects of management, and in turn, financial management is crucial for human resource management. Therefore, making a distinction between management functions is to some extent artificial in the context of devolution to middle managers, and this highlights the importance of integrating the organisations’ various functional areas.

Finally, devolution is not a purely objective phenomenon but has a significant component of subjectivity whose importance is socially constructed by those involved in it (Berger and Luckman, 1966). Consequently, one must consider not only the perspective of those who devolve management responsibilities (HR departments, top management, etc.), as indicated in the literature, but also the possibly differing perspectives of those to whom these responsibilities are devolved. This confirms the suitability of the qualitative methodology for exploring in-depth the meanings attributed to devolution by those involved and for distinguishing between how devolution is proposed by those in charge and how it is experienced by those who are affected by it. This latter point is an aspect that needs to be addressed in future research.

As for the main contribution of this study, both the identification of dimensions and their operationalization (implementation of tasks, decision-making power, financial power and expert power) have been shown to be useful in differentiating between different degrees of HRM devolution to middle managers. It is therefore a conceptual, methodological and practical contribution that enables managers of organisations to make a more accurate analysis of their own real situation. In this sense, it allows them to distinguish between different aspects of their organisations that have hitherto been referred to under the same umbrella term. This makes it also a useful tool for inter-organisational comparison, and it represents an important advance compared to the practice of simply recording the different areas of human resources that are devolved. The fact that operationalising the concept of devolution in this way should prove so effective also demonstrates the appropriateness of adopting an inductive approach in this particular field of study. It also shows the importance of carrying out this study phase, shown in cell 1 of the Snow and Thomas matrix (1994, see Table 1), before proceeding with explanatory and predictive research aims. In our opinion, the best way of building up knowledge is over a firm foundation, and to achieve this, it is necessary to operationalise concepts. Furthermore, the proposed operationalization allows us to distinguish between rhetoric and reality, that is, between stated intention to transfer HRM to middle managers and the extent to which this occurs and how those affected experience it. While the intention may be to create an autonomous middle management, the powers (decision-making, financial and expert power) necessary for this are not always devolved, either consciously or unconsciously, thus leading to a gap between rhetoric and reality. Hall and Torrington (1998b:51) and more recently Conway and Monks (2010) have also detected these differences between stated intention and reality in action.

In the light of the present study's results, we propose future research in two main areas that would address cells 2 and 4 of the Snow and Thomas matrix (1994, see Table 1). On one hand, cell 4 can be addressed by carrying out quantitative descriptive studies of different types of organisations to validate the effectiveness of operationalising the concept of HRM devolution to middle managers, bringing about exactitude in its measurement. Such studies would overcome the present study's limitations in terms of its lack of statistical generalisation typical of qualitative studies. In this sense it would be interesting to explore the degree of devolution in different organisations while taking into account different contextual and organisational variables such as the size of the organisation, the industry, etc. On the other hand, cell 2 could be addressed by examining the relationship between HRM devolution and other variables of interest, some of which have already been pointed out in the literature as the results of the process of devolution. These variables include the increased strategic role of HR departments (Renwick, 2000, 2003b; Budhwar, 2000; etc.), the economic performance of organisations (Azmi, 2010; Sheenan, 2012), the partnership between middle managers and the HR specialists (Currie and Procter, 2001; Gilbert et al., 2011a,b), and the relationship between the degree of devolution and the resulting perceptions of middle managers (such as empowerment, role conflict, role ambiguity and role overload). Furthermore, research into HRM devolution to middle managers has yet to explore the relationship between the “knowledge transfer” dimension and the other three dimensions identified in the present study (i.e. task, decision and budget). Such research would clarify whether knowledge transfer is another dimension of the concept of HRM devolution, whether it is a necessary prior condition that makes devolution possible, or whether it is an element that multiplies the efficacy of HRM devolution.

Finally, as a result of this exploratory study, as a conclusion of its theory building effort, and as a starting point for further research we put forward the following propositions:

Proposition 1: Devolution of HRM to MMs is a multidimensional phenomenon.

Proposition 2: Its dimensions are devolution of tasks, decision-making power, budgeting, and knowledge.

Proposition 3a: The devolution of task execution, decision-making power and budget is ordered from lowest to highest, with task execution representing a lower degree than decision-making power, and decision-making power representing a lower degree than budget.

Proposition 3b: The dimensions of tasks, decision-making power and budgeting occur cumulatively. In other words, when decision-making power is devolved, task execution is also devolved, and when financial power is devolved, tasks and decision-making power are also devolved. Meanwhile, budgeting is not devolved without tasks or decision-making power.

Proposition 4a: Knowledge transfer is a necessary condition for middle managers to be able to undertake their HRM responsibilities.

Proposition 4b: Knowledge transfer has a multiplying effect on the ability of middle managers to undertake their HRM responsibilities.

Proposition 5: When measuring devolution, one must take into account the number of human resource areas (selection, training, etc.) and the number of dimensions (tasks, decision-making, etc.) transferred to middle managers.

Proposition 6: Middle managers’ perceptions of the desirability of HRM devolution depend on the degree of devolution, and the coherence between transferred responsibilities and expected results.

We hope that this conceptual base, supported by the present empirical study, will enable more complex and analytically accurate future studies on devolution and its effects on middle managers and organisations.