Using a sample of 595 firms listed in the capital markets of Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru for the period of 2000–2015, we confirm prior literature by showing that when power distribution among several large shareholders (contestability) increases, firms’ financial performance is enhanced. More interestingly, we find that these relations are even more significant in family-owned firms, emphasising the relevance of contesting control in this kind of firm. Furthermore, contestability has a greater influence in family firms that have the most concentrated ownership. We also find that the legal framework attenuates the impact of the balance of ownership. Here, contesting control acts as an internal corporate governance mechanism that provides an alternative to the external legal setting. Taken together, our results mean that in institutional settings characterised by weak investor protection and possible conflicts of interest among shareholders, oversight by multiple large, non-related shareholders (balanced ownership concentration) becomes an important governance mechanism.

The discussion on the effect of ownership concentration has traditionally been based on two opposing views. One stresses the vertical dimension of corporate governance that stems from diluted ownership structures (Berle and Means, 1932; Jensen and Meckling, 1976), while the other shows that concentrated corporate ownership structures are present worldwide (Holderness, 2009; La Porta et al., 1999). More recently, the debate has focused on the effect of complex ownership structures involving several large shareholders (Cronqvist and Fahlenbrach, 2009; Gutiérrez and Pombo, 2009; Konijn et al., 2011; Mishra, 2011; Paligorova and Xu, 2012; Renders and Gaeremynck, 2012). In such structures, the idea of contestability of control arises, this being the motivation among secondary, non-related large shareholders to form coalitions in order to monitor or challenge dominant shareholder power (Huyghebaert and Wang, 2012; Maury and Pajuste, 2005).

An emerging stream of literature has shown that contesting the controlling owner by multiple large shareholders proves relevant for a number of different corporate finance issues such as firm value (Maury and Pajuste, 2005), implied cost of equity (Attig et al., 2008), firm reliance on bank debt financing (Lin et al., 2013), the maturity structure of debt (Ben-Nasr et al., 2015), and firm performance (Nagar et al., 2011), to name but a few.

Our objective is to analyse the effect of multiple large shareholders on firm value in the six biggest Latin American economies – Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru – and the moderating role played by the institutional framework.1 We combine two research features in order to make a unique contribution. First, we emphasise the specific corporate governance problems facing family owned firms when compared to their non-family owned counterparts. Second, we examine an international sample, which allows institutional environment factors that might shape the relationship between ownership structure and firm value to be included. Our paper's main contribution is thus to explore the differential effect of contesting control on the value of family owned firms (as compared to non-family owned ones) and how this effect is moderated by the institutional environment.

With the exception of Maury and Pajuste (2005), most research into the relationship between complex ownership structures and firm value has failed to take into account the specific issues involved in family firms. Although the agency relations between managers and shareholders are not as prominent in family-owned firms, this type of firm can be more prone to conflicts of interests between insiders (family members) and minority shareholders (Barontini and Caprio, 2006; Dyck and Zingales, 2004; Fiol and Aldrich, 1995; Isakov and Weisskopf, 2014).

Some prior research on the effect of multiple large shareholders has been carried out in a single country framework such as France, Finland, Spain or China (Ben-Nasr et al., 2015; Ben Saanoun et al., 2015; Cai et al., 2016; Maury and Pajuste, 2005; Ruiz Mallorquí and Santana Martín, 2011). Although some papers do have an international scope (Attig et al., 2009; Boubakri and Ghouma, 2010), the question regarding the impact of the institutional setting still demands further inquiry. In this vein, we aim to extend the findings of Huyghebaert and Wang (2012), who report weak evidence that the quality of institutions constrains expropriation to minority shareholders. In addition, we seek to contribute to the literature by furthering the evidence of Dow and McGuire (2016), who find that national institutional and cultural contexts are a key factor when determining the family's ability and willingness to exploit minority shareholder wealth.

Latin American countries provide an interesting scenario for our analysis for two reasons. First, the ownership structure in Latin America is highly concentrated, and lies mainly in the hands of family shareholders who control the firm. Second, even though there are also widely held firms, the civil-law origin of their institutional frameworks provides relatively little legal protection of investors’ rights (La Porta et al., 1998, 1999). In such a framework, the concentrated ownership structure may result in exacerbated conflicts of interest between majority and minority shareholders, such that contestability may serve as an effective addition to weaker legal protection.

In the Latin American arena, Gutiérrez and Pombo (2009) show that a more equal distribution of equity among large blockholders has a positive effect on firm value in Colombia. Similarly, Pombo and Taborda (2017) analyse the effect of power distribution in firms from several Latin American countries, and find that the existence and type of a second blockholder within firms with multiple blockholder structures proves to be a critical factor in explaining the effect on firm value.

Using a sample of 595 firms listed in the capital markets of Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru for the period 2000–2015, we confirm prior literature by showing that when power distribution among several large shareholders (contestability) increases, firms’ financial performance is enhanced. More interestingly, we find that these relations are even more significant in family-owned firms, thus underscoring the relevance of contesting control in this kind of firm. Furthermore, contestability is more relevant for family firms that have the most concentrated ownership. We also find that the legal framework attenuates the impact of the balance of ownership. Contesting control may thus be seen as an internal corporate governance mechanism that provides an alternative to the external legal setting. When taken together, our results suggest that, in institutional settings characterised by weak investor protection and possible conflicts of interests among shareholders, oversight by multiple large, non-related shareholders (balanced ownership concentration) proves to be a key governance mechanism. Our results are robust to different estimation methods and to alternative definitions of the variables. We also include a nearest-neighbour match analysis which validates the stochastic dominance in value of companies with higher contestability.

The remainder of the paper is organised as follows. Second section describes the related literature and the hypothesis development. Third section provides the source of information and the variables used in the empirical analysis. Fourth section proposes the methodology. Fifth section presents the estimation results of the models. Finally, sixth section concludes.

Theoretical review and hypothesesAlthough ownership concentration alleviates certain agency problems through direct manager supervision, excessive power concentration in the hands of a small number of shareholders may intensify the divergence of interests between controlling and minority shareholders (Ang et al., 2000; Davis et al., 1997; Guthrie and Sokolowsky, 2010).

Some recent literature has stressed the advantages of balanced corporate control where several large shareholders are involved (Huang et al., 2015; Mishra, 2011; Nagar et al., 2011; Santos et al., 2015). Specifically, the relative power of other large shareholders and their incentive to monitor the largest shareholders plays an important role in the corporate governance process. Multiple large shareholders interact with one another and with the dominant shareholder creating a specific dynamic inside the firm. In such ownership structures, when the largest shareholder does not have the control of the firm, two possible types of relations can emerge among shareholders. On the one hand, the collusion argument stresses the fact that the dominant shareholder can collude with other large shareholders, seeking wealth expropriation and diversion of corporate resources for private benefits at the expense of minority shareholders, with the subsequent firm value destruction (Edmans, 2014). On the other hand, monitoring arguments rely on the other large shareholders’ incentives to act alone or to form coalitions in order to engage in corporate governance activities – such as the “voice”, the threat of “exit”, or directly challenging the power of the controlling shareholder – which may potentially enhance firm value (Adjaoud and Ben-Amar, 2010; Bae et al., 2012).

Given such a framework, contestability is defined as the probability that non-dominant large shareholders will monitor or challenge the largest shareholder's power. This view argues that multiple large shareholder coalitions with large equity stakes result in stronger and more cohesive ownership, which enhances firm value (Bennedsen and Wolfenzon, 2000). The empirical literature endorses the positive effect which contesting control has on firm financial performance. Maury and Pajuste (2005) find that a more equal distribution of votes among large blockholders of Finnish firms has a positive effect on firm value. Similarly, Attig et al. (2008) find evidence for a sample of European and Asian firms that contesting control reduces financing costs, which eventually enhances firm value. Subsequently, Attig et al. (2009) examined ownership structures with multiple large shareholders and the effect on firm value for a sample of Asian firms. Their findings indicate that the presence, number, and size of such large shareholders implies a premium in firm value. More recently, Pombo and Taborda (2017) also found that contestability proves to be a critical factor in explaining the value of Latin American firms.

Although contestability seems to impact on the value of all firms, it is likely to be particularly relevant in family firms. Family-owned firms have been recognised as first-order importance agents to promote the growth of emerging economies (Morck, 2011; Wagner et al., 2015) and as a prevalent phenomenon in Latin America (Chong and Lopez-De-Silanes, 2007). Additionally, by their very monitoring structure and intrinsic cultural characteristics, family firms tend to have highly concentrated ownership, and even more so in developing countries (Fan et al., 2011). Hence, the possibility of coalitions among families in such firms increases with their subsequent ability to compel managers to pursue the majority or controlling shareholder interest.

We argue that the existence of other secondary large shareholders might be especially important in family firms, in which monitoring through contestability may prove particularly relevant in the case of agency problems between inside family shareholders and external shareholders (Blanco-Mazagatos et al., 2007; Miller and Le Breton-Miller, 2006; Moores, 2009). Family firm governance poses a number of problems for minority or non-family shareholders. Elistratova et al. (2016) show that related-party transactions are more often conducted by firms under family control. Value discount due to a disproportionate ownership structure is higher in family firms. Interestingly, this discount does not stem from different operational performance but rather from the (family) controlling shareholders extracting a disproportionate part of the quasi-rents in the firms they control (Bennedsen and Nielsen, 2010). Consistent evidence is reported by Laeven and Levine (2008), according to whom family shareholders are less likely to cooperate with other large shareholders. In this line, Pindado et al. (2011) indicate that family firms evidence less financial constraints when the second and third shareholders are non-family. Maury and Pajuste (2005) find that shareholder coalitions among families can make profit diversion easier.

In addition, Attig et al. (2008) find that the identity of the second shareholder is important for the risk of expropriation in family-owned firms, particularly in Eastern Asia where several large shareholders can supervise private benefit extraction and reduce financing costs. These authors conclude that when majority shareholders are families, information asymmetries increase, leading to a rise in capital costs. Consistent with this view, Sacristán-Navarro et al. (2015) argue that the effect of other large shareholders’ voting rights on minority investor wealth should be considered in family firms. In contrast, in coalitions between family and non-family members, the agreement to collude may be more difficult.

We argue that contestability should be important in family firms in situations in which the largest family shareholder has enough power to influence corporate decisions. The literature has pointed out that retaining control is a key aspect in family firms (Caprio et al., 2011). Particularly in Latin American countries, families use control enhancing mechanisms to maintain corporate control more than their non-family counterparts (Espinosa et al., 2017; González et al., 2012, 2014; Torres et al., 2017).2 A common feature of these structures is the greater voting power in the hands of the controlling family, which is unusual in non-family firms, where other types of investors hold diversified investment portfolios. In concentrated family owned firms, firms are typically run by managers who are often family members, with controlling families also being represented on the board of directors (Filatotchev et al., 2007).

We thus hypothesise that the existence of other large shareholders positively impacts on family firm value for two reasons. Firstly, other large shareholders may engage in monitoring by using the “voice” mechanism or the “threat of exit”, demanding value creating decisions (Edmans, 2014; Gompers and Metrick, 2001). Secondly, family firms often consider a longer time horizon and are concerned with the next generation's wealth (Filatochev et al., 2011), thus making them pay greater attention to reputation issues and value creation (Berrone et al., 2012; Gomez-Mejia et al., 2011).

We are also interested in the moderating effect of the institutional framework. Whereas balanced ownership structures seem to improve family firm value, it is also pertinent to wonder whether this effect might be reinforced by the institutional framework (Bennedsen et al., 2007). Indeed, prior research shows that the negative relation between the dispersion of cash flow rights and firm value is lower in countries that enjoy greater shareholder protection (Laeven and Levine, 2008). Chu et al. (2014) demonstrate that the higher equity cost induced by concentrated ownership structures is significantly reduced by a country's stronger legal and extra-legal institutions. In turn, the institutional setting also plays an important role. Dahya et al. (2008) find that other internal mechanisms may make up for the deficiencies of the institutional framework by providing the dominant shareholder with the incentives to enhance firm value.

Assuming the impact of contestability on firm value, and based on the above arguments, we propose the following two hypotheses:

H1: The positive effect of contesting the control of the largest shareholder on firm value is more prominent in family than in non-family firms in Latin America.

H2: The positive effect of contesting the control of the largest shareholder on firm value is less relevant when the quality of the institutional context is higher.

Our data set is made up of firm-level information from Thomson Reuters Eikon. Our final sample is composed of 5476 firm–year observations from 595 non-financial firms from Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru between 2000 and 2015.3

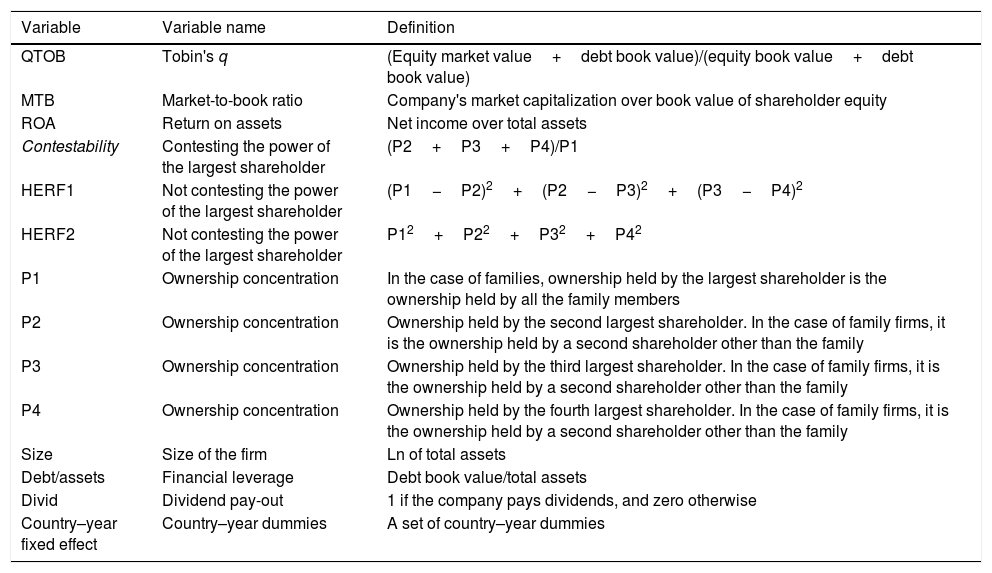

Table 1 presents the definitions of all the variables used in the empirical analysis. Following previous studies (Demsetz and Villalonga, 2001), our dependent variable is a proxy of Tobin's q. We measure Tobin's q as the market value of equity plus the book value of debt over the book value of total assets (QTOB). This variable is widely used in the literature and allows our results to be compared with previous research. We also use the market-to-book (MTB) ratio and the return on assets (ROA).

Definition of variables.

| Variable | Variable name | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| QTOB | Tobin's q | (Equity market value+debt book value)/(equity book value+debt book value) |

| MTB | Market-to-book ratio | Company's market capitalization over book value of shareholder equity |

| ROA | Return on assets | Net income over total assets |

| Contestability | Contesting the power of the largest shareholder | (P2+P3+P4)/P1 |

| HERF1 | Not contesting the power of the largest shareholder | (P1−P2)2+(P2−P3)2+(P3−P4)2 |

| HERF2 | Not contesting the power of the largest shareholder | P12+P22+P32+P42 |

| P1 | Ownership concentration | In the case of families, ownership held by the largest shareholder is the ownership held by all the family members |

| P2 | Ownership concentration | Ownership held by the second largest shareholder. In the case of family firms, it is the ownership held by a second shareholder other than the family |

| P3 | Ownership concentration | Ownership held by the third largest shareholder. In the case of family firms, it is the ownership held by a second shareholder other than the family |

| P4 | Ownership concentration | Ownership held by the fourth largest shareholder. In the case of family firms, it is the ownership held by a second shareholder other than the family |

| Size | Size of the firm | Ln of total assets |

| Debt/assets | Financial leverage | Debt book value/total assets |

| Divid | Dividend pay-out | 1 if the company pays dividends, and zero otherwise |

| Country–year fixed effect | Country–year dummies | A set of country–year dummies |

The first right-hand side variable is contestability, which is an index reflecting the power of the other large shareholders who are not the controlling shareholder. In line with previous studies (Maury and Pajuste, 2005; Pombo and Taborda, 2017), we compute contestability as the voting power of the secondary largest shareholders (second, third and fourth largest shareholders) over the voting power of the first largest shareholder. Given the ownership features of the Latin American corporate environment (e.g., pyramidal ownership, dual class shares, business groups, blockholders from the same family, among others), it is crucial to know the identity of each shareholder in order to correctly compute their effective voting power. For instance, the first, second and third shareholder in a firm may be the same (shareholder) because the largest shareholder may control the firm indirectly through pyramidal control or may belong to the same family group. We take great care when dealing with these problems.

Alternatively, we use HERF1 and HERF2 as measures of not contesting the largest shareholder's power.4 Consequently, the higher this index, the lower the capacity of secondary large shareholders to contest or monitor the controlling shareholder.

In the Latin-American context, firms may be controlled by the same family through different family members or through closed companies. Consequently, for the empirical analysis it is crucial to check the identity of the shareholders. Accordingly, we thoroughly check ownership structure year by year and firm by firm. This process allows us to identify the owner's effective voting power in a firm – that is, the shareholder who actually controls the firm. Once we identify the largest shareholder (and family), we estimate our contestability measures. A similar process was carried out to identify family firms. According to similar research (Bonilla et al., 2010), family firms are identified based on the following process. First, while we check the identity of each shareholder, we establish the family nature of these shareholders. Second, we also categorise a firm as family-owned when the largest shareholder is an individual who maintains family ties with other relevant shareholders (groups of individuals from the same family). We consider a group of individuals who own at least 10% of the voting rights in the company to be family shareholders (Almeida and Wolfenzon, 2006; Ampenberger et al., 2013).

Additionally, we use a number of control variables to avoid problems of under specification of our models and to enhance the comparability of our analysis with prior literature (Attig et al., 2008; Gutiérrez and Pombo, 2009; Harris and Raviv, 1988). Size is a proxy for firm size, measured as the natural logarithm of the firm's total assets. Debt/Assets measures financial leverage (total debt over total assets). Divid is a dummy variable that equals 1 if the firm pays out cash dividends in a given fiscal year, and zero otherwise. When appropriate, firm, industry, country, and time dummy control variables were included in the regression models.

MethodologyThe empirical analysis is divided into two stages. First, we run a descriptive analysis to show the main characteristics of our sample and the basic relations among the corporate ownership variables (contestability, ownership concentration, and family ownership, among others) and firm performance. The second stage tests our hypotheses through explanatory analysis. In order to check the consistency of our results, we run several alternative models with different variables and estimation methods.

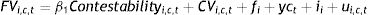

The baseline analysis model is based on Eq. (1), in which firm value depends on contestability of control, and the control variables:

where FVi,c,t is the value of firm i in country c and in period t (e.g. QTOB, MTB or ROA). Contestabilityi,c,t is the contestability variable and CVi,c,t is the vector of control variables (e.g. Size, Debt/Assets, and Divid). We also incorporate a set of dummy variables to control for country–year fixed effects and industry fixed effects.Our database combines time-series with cross-sectional data, allowing the formation of panel data. Consequently, our explanatory analysis is based on panel data estimations (Arellano, 2002). There are two main concerns when dealing with panel data: the problems of unobservable heterogeneity and endogeneity. Heterogeneity refers to the unobserved, time-invariant differences across firms. As regards the endogeneity problem, corporate governance literature suggests three main sources of this particular econometric drawback: unobserved characteristics of corporations, simultaneity, and so-called dynamic endogeneity (Pindado et al., 2012; Roberts and Whited, 2013; Wintoki et al., 2012). We control for dynamic endogeneity by introducing the lagged term of the dependent variable, and for simultaneity by estimating our regressions using generalised method of moments (GMM) estimations in which we introduce the lagged explanatory variables as instruments. In general, using OLS estimations can provide coefficients that are biased due to the correlation between the fixed effects and the lagged dependent variable (Baltagi, 2013). Thus, the Blundell and Bond (1998) GMM system estimator is used. The GMM system estimator deals efficiently with endogeneity issues in the relation between performance and ownership features. In general, all the right-hand side variables are potentially endogenous (Pindado et al., 2011).

One important feature of the GMM method is that it controls for endogeneity of all firm-level variables by introducing lagged right-hand side variables as instruments. Specifically, we introduce all right-hand side variables lagged from t-1 to t-3 when estimating equation 1. Thus, the GMM system estimator displays certain advantages over other dynamic panel models that are commonly used in corporate finance research, such as small root-mean squared errors (RMSEs) when estimating a dependent variable's persistence. Regardless of the true (high or low) value, the GMM system estimator outperforms the fixed effect method (estimating a highly persistent lag coefficient), is unaffected by panel imbalance, and is consistent across a range of endogeneity in the presence of serial correlation (Flannery and Hankins, 2013).

Moreover, the Blundell and Bond (1998) GMM system estimator outperforms the original Arellano and Bond (1991) difference GMM by making the additional assumption that first differences of instrumental variables are uncorrelated with fixed effects. This allows for the inclusion of more instruments that dramatically improve efficiency (Roodman, 2008). In fact, the difference GMM can perform poorly in comparison to the GMM system estimator if the ratio of the variance of the panel-level effect to the variance of the idiosyncratic error is too large. Consequently, the GMM system estimator emerges as an enhanced technique compared to the original difference GMM technique, because it expands the instrument lists by including instruments that improve efficiency.5

The consistency of the estimates depends to a great extent on the absence of second-order serial autocorrelation in the residuals and on instrument validity (Arellano and Bond, 1991). Accordingly, p-values of the first and second order autocorrelation tests are reported. To test the validity of the instruments, the Hansen test of overidentifying constraints is used, testing for the absence of correlation between the instruments and the error term and, therefore, checking the validity of the selected instruments. Finally, all the estimations across tables were estimated by clustering errors at firm-level due to the movements of the variables of interest.

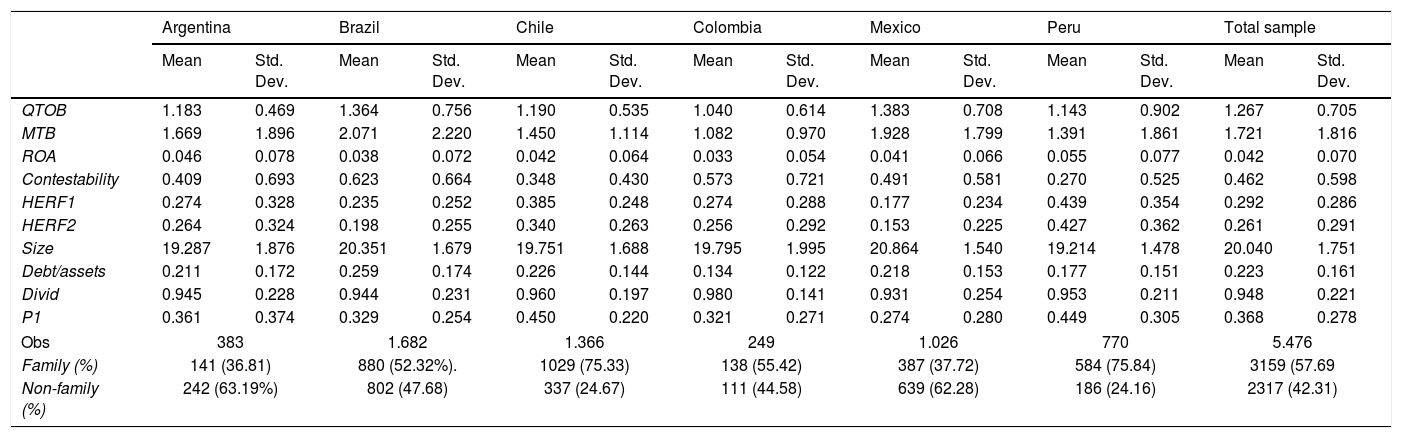

ResultsDescriptive analysisTable 2 provides the mean and standard deviation for each variable at firm and country level. The picture to emerge is one of highly concentrated corporate ownership, consistent with other research into Latin America (Chong and Lopez-De-Silanes, 2007; Chong et al., 2009; Gutiérrez and Pombo, 2009; Johnson and Shleifer, 2000; Lefort, 2005; Lefort and Walker, 2000; Saona and San Martín, 2016). The largest shareholder (P1) holds about 36.8% of the shares for the total sample – Peru (44.9%) and Mexico (27.4%) are the extreme cases. As expected, the countries with the highest ownership concentration (P1 variable) have the lowest levels of contestability (Contestability, HERF1, and HERF2). On average, the contestability variable confirms the high level of ownership concentration, revealing that for every share in the hands of the controller, there are 0.46 shares in the hands of the second, the third, and the fourth major shareholders. The most balanced ownership structure in Latin American countries is found in Brazil (mean=0.623) and the most concentrated in Peru (mean=0.270). The HERF1 and HERF2 variables (lack of contestability) give the same information. For all the countries in the study, the average Tobin's q is above one (1.267), with the lowest value being for Colombian firms (1.040). On average, the leverage of our sample is 22.3%, with the maximum in Brazilian firms (25.9%) and the lowest value in Colombian companies (13.4%). Most of the firms in the sample do pay out dividends (payout ratio of about 94.8%).

Descriptive statistics across countries.

| Argentina | Brazil | Chile | Colombia | Mexico | Peru | Total sample | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Std. Dev. | Mean | Std. Dev. | Mean | Std. Dev. | Mean | Std. Dev. | Mean | Std. Dev. | Mean | Std. Dev. | Mean | Std. Dev. | |

| QTOB | 1.183 | 0.469 | 1.364 | 0.756 | 1.190 | 0.535 | 1.040 | 0.614 | 1.383 | 0.708 | 1.143 | 0.902 | 1.267 | 0.705 |

| MTB | 1.669 | 1.896 | 2.071 | 2.220 | 1.450 | 1.114 | 1.082 | 0.970 | 1.928 | 1.799 | 1.391 | 1.861 | 1.721 | 1.816 |

| ROA | 0.046 | 0.078 | 0.038 | 0.072 | 0.042 | 0.064 | 0.033 | 0.054 | 0.041 | 0.066 | 0.055 | 0.077 | 0.042 | 0.070 |

| Contestability | 0.409 | 0.693 | 0.623 | 0.664 | 0.348 | 0.430 | 0.573 | 0.721 | 0.491 | 0.581 | 0.270 | 0.525 | 0.462 | 0.598 |

| HERF1 | 0.274 | 0.328 | 0.235 | 0.252 | 0.385 | 0.248 | 0.274 | 0.288 | 0.177 | 0.234 | 0.439 | 0.354 | 0.292 | 0.286 |

| HERF2 | 0.264 | 0.324 | 0.198 | 0.255 | 0.340 | 0.263 | 0.256 | 0.292 | 0.153 | 0.225 | 0.427 | 0.362 | 0.261 | 0.291 |

| Size | 19.287 | 1.876 | 20.351 | 1.679 | 19.751 | 1.688 | 19.795 | 1.995 | 20.864 | 1.540 | 19.214 | 1.478 | 20.040 | 1.751 |

| Debt/assets | 0.211 | 0.172 | 0.259 | 0.174 | 0.226 | 0.144 | 0.134 | 0.122 | 0.218 | 0.153 | 0.177 | 0.151 | 0.223 | 0.161 |

| Divid | 0.945 | 0.228 | 0.944 | 0.231 | 0.960 | 0.197 | 0.980 | 0.141 | 0.931 | 0.254 | 0.953 | 0.211 | 0.948 | 0.221 |

| P1 | 0.361 | 0.374 | 0.329 | 0.254 | 0.450 | 0.220 | 0.321 | 0.271 | 0.274 | 0.280 | 0.449 | 0.305 | 0.368 | 0.278 |

| Obs | 383 | 1.682 | 1.366 | 249 | 1.026 | 770 | 5.476 | |||||||

| Family (%) | 141 (36.81) | 880 (52.32%). | 1029 (75.33) | 138 (55.42) | 387 (37.72) | 584 (75.84) | 3159 (57.69 | |||||||

| Non-family (%) | 242 (63.19%) | 802 (47.68) | 337 (24.67) | 111 (44.58) | 639 (62.28) | 186 (24.16) | 2317 (42.31) | |||||||

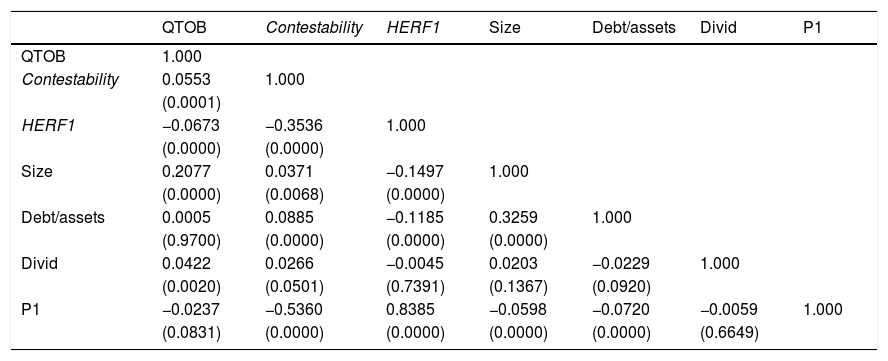

In Table 3, we report the correlation matrix. As can be seen, there are no significantly high correlation coefficients among the independent variables. Nevertheless, as expected and by construction, ownership concentration (P1) is highly and positively correlated with the contestability variables (Contestability and HERF1 and HERF2). Firm size (Size) is positively correlated with leverage (Debt/Assets), which makes sense since trim size is a source of reputation that allows companies to finance their investments with greater proportions of long-term debt. Despite this correlation between these two variables, variance inflation factor tests (not tabulated) do not report any problems of multicollinearity in the regression outputs.

Correlation matrix.

| QTOB | Contestability | HERF1 | Size | Debt/assets | Divid | P1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QTOB | 1.000 | ||||||

| Contestability | 0.0553 | 1.000 | |||||

| (0.0001) | |||||||

| HERF1 | −0.0673 | −0.3536 | 1.000 | ||||

| (0.0000) | (0.0000) | ||||||

| Size | 0.2077 | 0.0371 | −0.1497 | 1.000 | |||

| (0.0000) | (0.0068) | (0.0000) | |||||

| Debt/assets | 0.0005 | 0.0885 | −0.1185 | 0.3259 | 1.000 | ||

| (0.9700) | (0.0000) | (0.0000) | (0.0000) | ||||

| Divid | 0.0422 | 0.0266 | −0.0045 | 0.0203 | −0.0229 | 1.000 | |

| (0.0020) | (0.0501) | (0.7391) | (0.1367) | (0.0920) | |||

| P1 | −0.0237 | −0.5360 | 0.8385 | −0.0598 | −0.0720 | −0.0059 | 1.000 |

| (0.0831) | (0.0000) | (0.0000) | (0.0000) | (0.0000) | (0.6649) |

This table shows the correlation coefficient between the study variables. Contestability is the power distribution variable; HERF1 is a measure of ownership concentration and the lack of contestability of the largest shareholder's power; QTOB is Tobin's q; Divid is the dividend payout variable; Size is the log of total assets per company; Debt/assets is the financial leverage; P1 is the voting rights of the largest shareholder. p-Values are in parenthesis beneath each correlation coefficient.

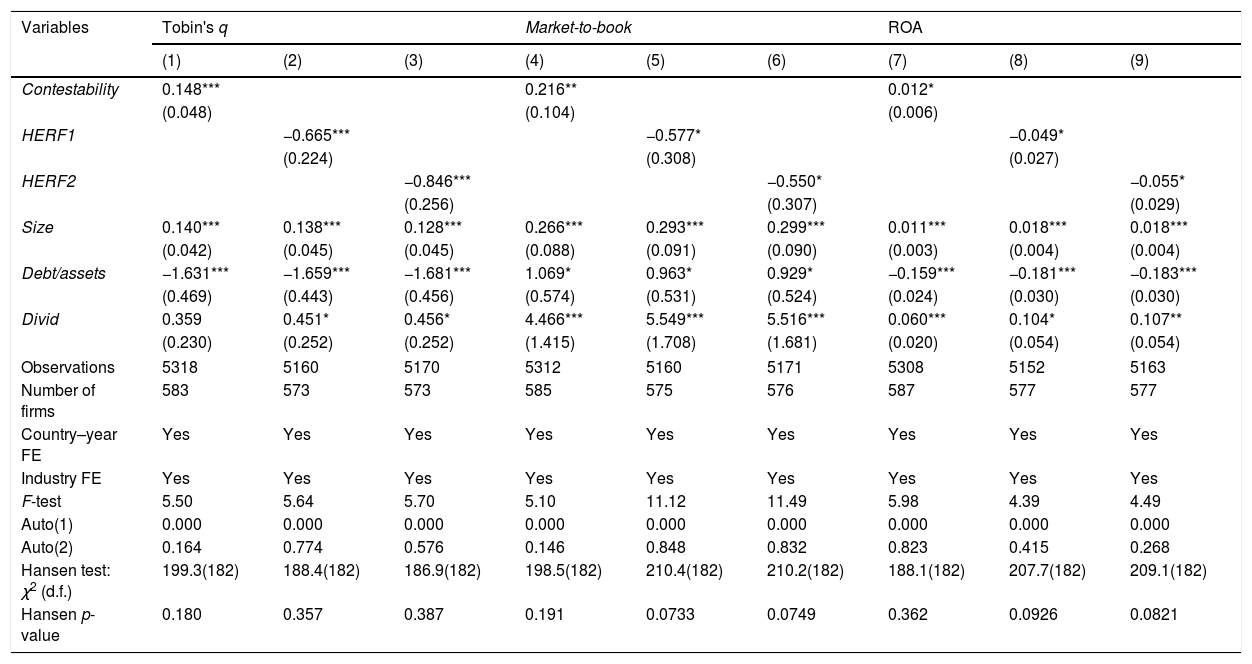

Table 4a shows the results of the baseline model using the generalised method of moments (GMM). The nine alternative regressions are grouped based on the three dependent variables (QTOB, MTB, and ROA). As expected, and consistent with prior research, the impact of the contestability variable on firm value is positive and statistically significant across columns 1, 4 and 7 of Table 4a using Tobin's q, market-to-book ratio, and return on assets, respectively, as the dependent variable. This finding suggests that, on average, contestability of control alleviates agency problems and boosts firms’ performance in contexts of relatively high ownership concentration such as in Latin American firms (Gutiérrez and Pombo, 2009). Hence, the greater the contestability of control, reflected in a more balanced distribution of control rights among the multiple large non-related shareholders, the higher the market value.

Contestability of control and firm performance: generalised method of moments.

| Variables | Tobin's q | Market-to-book | ROA | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | |

| Contestability | 0.148*** | 0.216** | 0.012* | ||||||

| (0.048) | (0.104) | (0.006) | |||||||

| HERF1 | −0.665*** | −0.577* | −0.049* | ||||||

| (0.224) | (0.308) | (0.027) | |||||||

| HERF2 | −0.846*** | −0.550* | −0.055* | ||||||

| (0.256) | (0.307) | (0.029) | |||||||

| Size | 0.140*** | 0.138*** | 0.128*** | 0.266*** | 0.293*** | 0.299*** | 0.011*** | 0.018*** | 0.018*** |

| (0.042) | (0.045) | (0.045) | (0.088) | (0.091) | (0.090) | (0.003) | (0.004) | (0.004) | |

| Debt/assets | −1.631*** | −1.659*** | −1.681*** | 1.069* | 0.963* | 0.929* | −0.159*** | −0.181*** | −0.183*** |

| (0.469) | (0.443) | (0.456) | (0.574) | (0.531) | (0.524) | (0.024) | (0.030) | (0.030) | |

| Divid | 0.359 | 0.451* | 0.456* | 4.466*** | 5.549*** | 5.516*** | 0.060*** | 0.104* | 0.107** |

| (0.230) | (0.252) | (0.252) | (1.415) | (1.708) | (1.681) | (0.020) | (0.054) | (0.054) | |

| Observations | 5318 | 5160 | 5170 | 5312 | 5160 | 5171 | 5308 | 5152 | 5163 |

| Number of firms | 583 | 573 | 573 | 585 | 575 | 576 | 587 | 577 | 577 |

| Country–year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| F-test | 5.50 | 5.64 | 5.70 | 5.10 | 11.12 | 11.49 | 5.98 | 4.39 | 4.49 |

| Auto(1) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Auto(2) | 0.164 | 0.774 | 0.576 | 0.146 | 0.848 | 0.832 | 0.823 | 0.415 | 0.268 |

| Hansen test: χ2 (d.f.) | 199.3(182) | 188.4(182) | 186.9(182) | 198.5(182) | 210.4(182) | 210.2(182) | 188.1(182) | 207.7(182) | 209.1(182) |

| Hansen p-value | 0.180 | 0.357 | 0.387 | 0.191 | 0.0733 | 0.0749 | 0.362 | 0.0926 | 0.0821 |

Estimated coefficients (robust standard errors clustered at firm level) from the GMM panel data regressions of Eq. (1). Our dependent variables are: Q TOBi,c,t, that is Tobin's q; MTBi,c,t, that is the market-to-book ratio; and ROAi,c,t, that is the return on assets. Contestabilityi,c,t represents the contestability variable. The independent variables are defined in Table 1. We include fixed effects at country–year level (Cc) and industry level (qt).

In order to check the average effect of contestability on performance, we use two additional measures of lack of contestability (based on ownership dispersion or Herfindahl measures), HERF1 and HERF2. The other columns in Table 4a show a negative and statistically significant relationship between the lack of contestability variables and firm value, and suggest that the absence of contestability has a detrimental effect on firm performance. HERF variables are relative measures of corporate ownership concentration in the hands of majority shareholders. Inherently, higher HERF measure values indicate diluted contestability power (e.g. lack of contestability). Quantitatively, HERF1 (HERF2) negatively impacts on our three dependent variables. Column 2 (Column 3) shows that the effect is −0.665 (−0.846) on Tobin's q, Column 5 (Column 6) shows that the effect is −0.577 (−0.550) on market-to-book ratio, and in Column 8 (Column 9) the effect is −0.049 (−0.055).

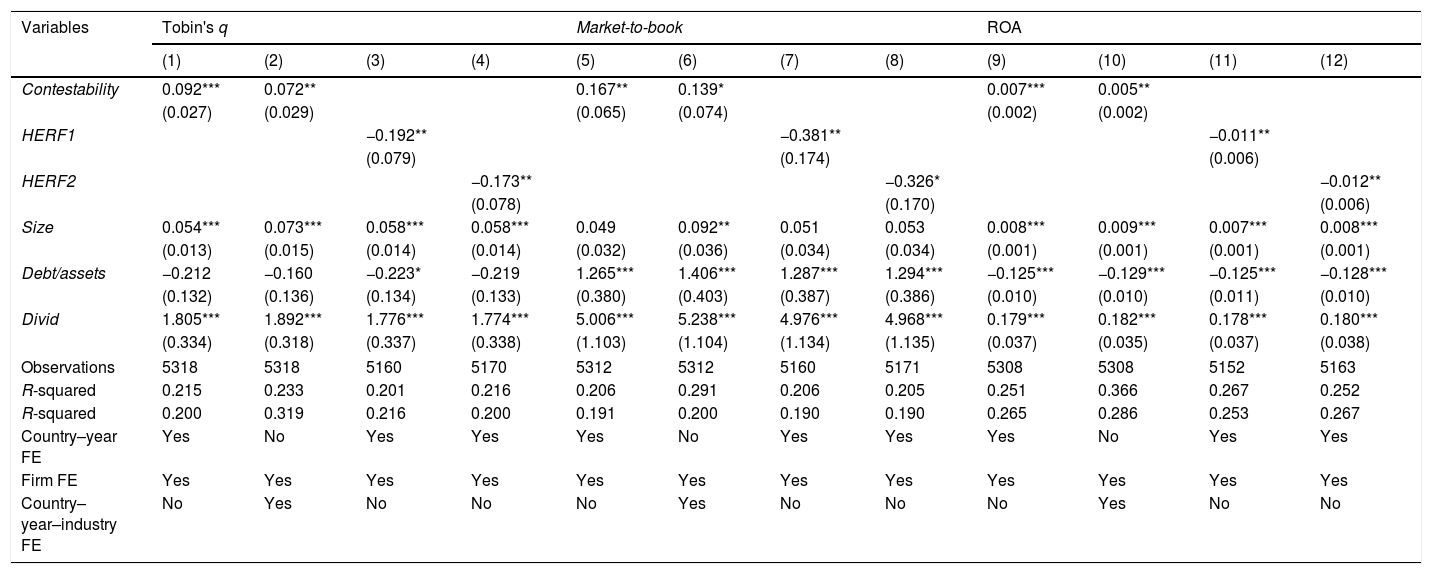

In order to verify the consistency and robustness of our results, we estimate Eq. (1) using OLS regressions (see Table 4b) and introduce a stricter set of fixed effects. For instance, in Column 2 we introduce an interacted country–year–industry fixed effect to control for those unobservable time-invariant and time-variant fixed effects that come from a country and an industry at the same time. In addition, we also introduce firm fixed effect to control for those unobservable time-invariant characteristics of the firm. The results observed across all the columns of Table 4b are qualitatively similar to those obtained in Table 4a.

Contestability of control and firm performance: OLS-fixed effect estimates.

| Variables | Tobin's q | Market-to-book | ROA | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) | |

| Contestability | 0.092*** | 0.072** | 0.167** | 0.139* | 0.007*** | 0.005** | ||||||

| (0.027) | (0.029) | (0.065) | (0.074) | (0.002) | (0.002) | |||||||

| HERF1 | −0.192** | −0.381** | −0.011** | |||||||||

| (0.079) | (0.174) | (0.006) | ||||||||||

| HERF2 | −0.173** | −0.326* | −0.012** | |||||||||

| (0.078) | (0.170) | (0.006) | ||||||||||

| Size | 0.054*** | 0.073*** | 0.058*** | 0.058*** | 0.049 | 0.092** | 0.051 | 0.053 | 0.008*** | 0.009*** | 0.007*** | 0.008*** |

| (0.013) | (0.015) | (0.014) | (0.014) | (0.032) | (0.036) | (0.034) | (0.034) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| Debt/assets | −0.212 | −0.160 | −0.223* | −0.219 | 1.265*** | 1.406*** | 1.287*** | 1.294*** | −0.125*** | −0.129*** | −0.125*** | −0.128*** |

| (0.132) | (0.136) | (0.134) | (0.133) | (0.380) | (0.403) | (0.387) | (0.386) | (0.010) | (0.010) | (0.011) | (0.010) | |

| Divid | 1.805*** | 1.892*** | 1.776*** | 1.774*** | 5.006*** | 5.238*** | 4.976*** | 4.968*** | 0.179*** | 0.182*** | 0.178*** | 0.180*** |

| (0.334) | (0.318) | (0.337) | (0.338) | (1.103) | (1.104) | (1.134) | (1.135) | (0.037) | (0.035) | (0.037) | (0.038) | |

| Observations | 5318 | 5318 | 5160 | 5170 | 5312 | 5312 | 5160 | 5171 | 5308 | 5308 | 5152 | 5163 |

| R-squared | 0.215 | 0.233 | 0.201 | 0.216 | 0.206 | 0.291 | 0.206 | 0.205 | 0.251 | 0.366 | 0.267 | 0.252 |

| R-squared | 0.200 | 0.319 | 0.216 | 0.200 | 0.191 | 0.200 | 0.190 | 0.190 | 0.265 | 0.286 | 0.253 | 0.267 |

| Country–year FE | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Firm FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Country–year–industry FE | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | No |

Estimated coefficients (robust standard errors clustered at firm level) from the OLS panel data regressions of Eq. (1). Our dependent variables are: Q TOBi,c,t, that is Tobin's q; MTBi,c,t, that is the market-to-book ratio; and ROAi,c,t, that is the return on assets. Contestabilityi,c,t represents the contestability variable. The independent variables are defined in Table 1. We include fixed effects at country–year level (Cc) and industry level (qt).

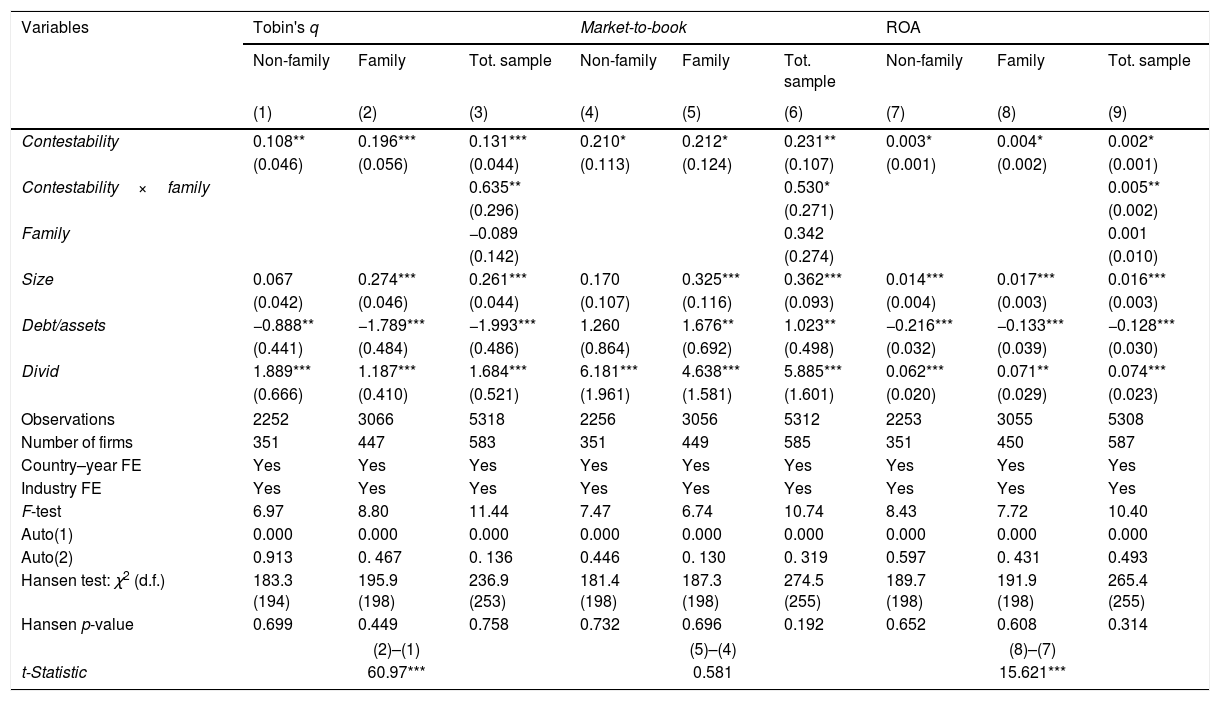

Our first hypothesis anticipates a heterogeneous response of firm value to contestability in family and non-family firms. We address this issue in Table 5 by splitting the sample into family and non-family firms and by showing the interacted term of family-controlled firms for the total sample. The results in Columns 1 and 2 of Table 5 show that contestability positively impacts on financial value in both family and non-family firms.6 In sum, the existence of multiple large shareholders proves to be relevant in both family and non-family firms, such that the higher the power distribution among several large shareholders, the higher the firm value.

Contestability, family vs. non-family nature: generalised method of moments.

| Variables | Tobin's q | Market-to-book | ROA | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-family | Family | Tot. sample | Non-family | Family | Tot. sample | Non-family | Family | Tot. sample | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | |

| Contestability | 0.108** | 0.196*** | 0.131*** | 0.210* | 0.212* | 0.231** | 0.003* | 0.004* | 0.002* |

| (0.046) | (0.056) | (0.044) | (0.113) | (0.124) | (0.107) | (0.001) | (0.002) | (0.001) | |

| Contestability×family | 0.635** | 0.530* | 0.005** | ||||||

| (0.296) | (0.271) | (0.002) | |||||||

| Family | −0.089 | 0.342 | 0.001 | ||||||

| (0.142) | (0.274) | (0.010) | |||||||

| Size | 0.067 | 0.274*** | 0.261*** | 0.170 | 0.325*** | 0.362*** | 0.014*** | 0.017*** | 0.016*** |

| (0.042) | (0.046) | (0.044) | (0.107) | (0.116) | (0.093) | (0.004) | (0.003) | (0.003) | |

| Debt/assets | −0.888** | −1.789*** | −1.993*** | 1.260 | 1.676** | 1.023** | −0.216*** | −0.133*** | −0.128*** |

| (0.441) | (0.484) | (0.486) | (0.864) | (0.692) | (0.498) | (0.032) | (0.039) | (0.030) | |

| Divid | 1.889*** | 1.187*** | 1.684*** | 6.181*** | 4.638*** | 5.885*** | 0.062*** | 0.071** | 0.074*** |

| (0.666) | (0.410) | (0.521) | (1.961) | (1.581) | (1.601) | (0.020) | (0.029) | (0.023) | |

| Observations | 2252 | 3066 | 5318 | 2256 | 3056 | 5312 | 2253 | 3055 | 5308 |

| Number of firms | 351 | 447 | 583 | 351 | 449 | 585 | 351 | 450 | 587 |

| Country–year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| F-test | 6.97 | 8.80 | 11.44 | 7.47 | 6.74 | 10.74 | 8.43 | 7.72 | 10.40 |

| Auto(1) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Auto(2) | 0.913 | 0. 467 | 0. 136 | 0.446 | 0. 130 | 0. 319 | 0.597 | 0. 431 | 0.493 |

| Hansen test: χ2 (d.f.) | 183.3 (194) | 195.9 (198) | 236.9 (253) | 181.4 (198) | 187.3 (198) | 274.5 (255) | 189.7 (198) | 191.9 (198) | 265.4 (255) |

| Hansen p-value | 0.699 | 0.449 | 0.758 | 0.732 | 0.696 | 0.192 | 0.652 | 0.608 | 0.314 |

| (2)–(1) | (5)–(4) | (8)–(7) | |||||||

| t-Statistic | 60.97*** | 0.581 | 15.621*** | ||||||

Estimated coefficients (robust standard errors clustered at firm level) from the GMM panel data regressions of Eq. (1) for subsamples of family and non-family definition. Our dependent variables are: Q TOBi, that is Tobin's q; MTBi,c,t, that is the market-to-book ratio; and ROAi,c,t, that is the return on assets. Contestabilityi,c,t represents the contestability variable. The independent variables are defined in Table 1. We include fixed effects at the firm level (fi), country level (Cc) and year level (qt).

In order to analyse whether power distribution is more important in family or non-family firms, we estimate Eq. (1) for the full sample and introduce an interacted term of family nature and contestability (Contestability×family). Columns 3, 6, and 9 show that the contestability coefficient is positive and significant in all the specifications, irrespective of the dependent variable (QTOB in Column 3, MTB in Column 6, and ROA in Column 9). Interestingly, the columns also show that the estimate of the Contestability×family interaction is positive and statistically significant. These results suggest that, although contestability of control increases the value of all the firms, it has an additional relevant influence on the value of family firms. Furthermore, the Contestability×family variable coefficients are twice as large as those of the contestability variable, thus supporting the specific and incremental effect of balanced ownership structures on the value of family firms.

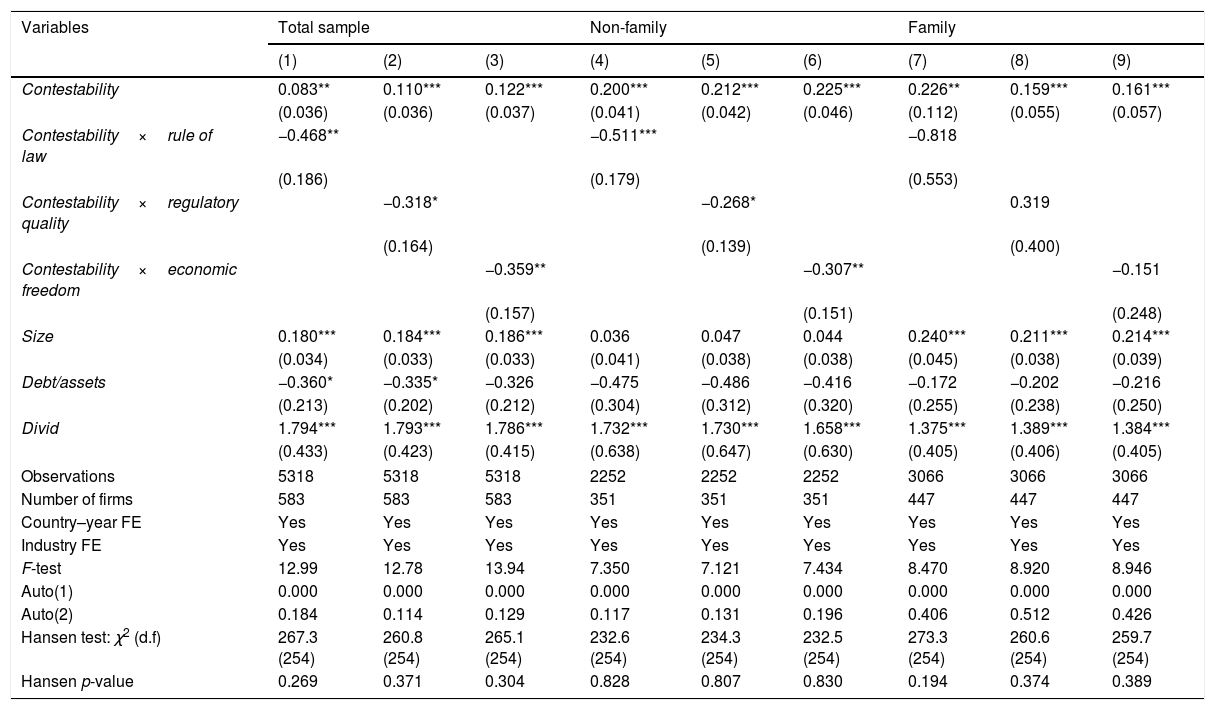

The moderating effect of country characteristicsHaving estimated the average effect of contestability on firm value in Table 6 we now explore whether these effects are different across countries by checking some possible institutional characteristics that proxy investor protection at the country level. We consider three moderating factors. First and second, following La Porta et al. (2000), we introduce the Rule of Law and Regulatory Quality, obtained from the World Governance Indicators provided by the World Bank. Third, we introduce the economic freedom indicator, obtained from the Heritage Foundation.

Contestability of control and firm value – institutional feature moderators (Tobin's q as dependent var.).

| Variables | Total sample | Non-family | Family | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | |

| Contestability | 0.083** | 0.110*** | 0.122*** | 0.200*** | 0.212*** | 0.225*** | 0.226** | 0.159*** | 0.161*** |

| (0.036) | (0.036) | (0.037) | (0.041) | (0.042) | (0.046) | (0.112) | (0.055) | (0.057) | |

| Contestability×rule of law | −0.468** | −0.511*** | −0.818 | ||||||

| (0.186) | (0.179) | (0.553) | |||||||

| Contestability×regulatory quality | −0.318* | −0.268* | 0.319 | ||||||

| (0.164) | (0.139) | (0.400) | |||||||

| Contestability×economic freedom | −0.359** | −0.307** | −0.151 | ||||||

| (0.157) | (0.151) | (0.248) | |||||||

| Size | 0.180*** | 0.184*** | 0.186*** | 0.036 | 0.047 | 0.044 | 0.240*** | 0.211*** | 0.214*** |

| (0.034) | (0.033) | (0.033) | (0.041) | (0.038) | (0.038) | (0.045) | (0.038) | (0.039) | |

| Debt/assets | −0.360* | −0.335* | −0.326 | −0.475 | −0.486 | −0.416 | −0.172 | −0.202 | −0.216 |

| (0.213) | (0.202) | (0.212) | (0.304) | (0.312) | (0.320) | (0.255) | (0.238) | (0.250) | |

| Divid | 1.794*** | 1.793*** | 1.786*** | 1.732*** | 1.730*** | 1.658*** | 1.375*** | 1.389*** | 1.384*** |

| (0.433) | (0.423) | (0.415) | (0.638) | (0.647) | (0.630) | (0.405) | (0.406) | (0.405) | |

| Observations | 5318 | 5318 | 5318 | 2252 | 2252 | 2252 | 3066 | 3066 | 3066 |

| Number of firms | 583 | 583 | 583 | 351 | 351 | 351 | 447 | 447 | 447 |

| Country–year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| F-test | 12.99 | 12.78 | 13.94 | 7.350 | 7.121 | 7.434 | 8.470 | 8.920 | 8.946 |

| Auto(1) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Auto(2) | 0.184 | 0.114 | 0.129 | 0.117 | 0.131 | 0.196 | 0.406 | 0.512 | 0.426 |

| Hansen test: χ2 (d.f) | 267.3 (254) | 260.8 (254) | 265.1 (254) | 232.6 (254) | 234.3 (254) | 232.5 (254) | 273.3 (254) | 260.6 (254) | 259.7 (254) |

| Hansen p-value | 0.269 | 0.371 | 0.304 | 0.828 | 0.807 | 0.830 | 0.194 | 0.374 | 0.389 |

Estimated coefficients (robust standard errors clustered at firm level) from the GMM panel data regressions of Eq. (1) for total sample and subsamples for family and non-family definition. Our dependent variables are: Q TOBi, that is Tobin's q; MTBi,c,t, that is the market-to-book ratio; and ROAi,c,t, that is the return on assets. Contestabilityi,c,t represents the contestability variable. The independent variables are defined in Table 1. We include fixed effects at the firm level (fi), country level (Cc) and year level (qt).

Results across all columns of Table 6 show that the standard contestability coefficient is positive and statistically significant. However, this effect is counterbalanced by the negative and statistically significant coefficient of the interacted term Contestability×Rule of Law for the total sample (Column 1) and for the non-family firms subset (Column 4). In contrast, the coefficient of the interacted variable is not statistically significant for family firms (Column 7). Similar results can be seen when we introduce the Contestability×Regulatory Quality and Contestability×Economic Freedom interaction, respectively. Confirming our second hypothesis, broadly speaking, our results suggest that the better a country's institutions, the lower the positive effect of contestability on firm value, with these results being driven by the subset of non-family firms. This bears out the beneficial role multiple large shareholders play as a complementary corporate governance mechanism in countries that lack sufficient external investor protection.

To some extent, the results from family firms might be considered counterintuitive since the effect of contestability is not moderated by institutional factors in this type of firm. Nevertheless, unlike their non-family counterparts, the results reported in Table 7 confirm the specific nature of the conflicts among shareholders in family firms. From this point of view, balanced ownership structures prove particularly effective and are so crucial in family firms that even a more protective legal framework is not as effectual as the involvement of several large shareholders in these firms.

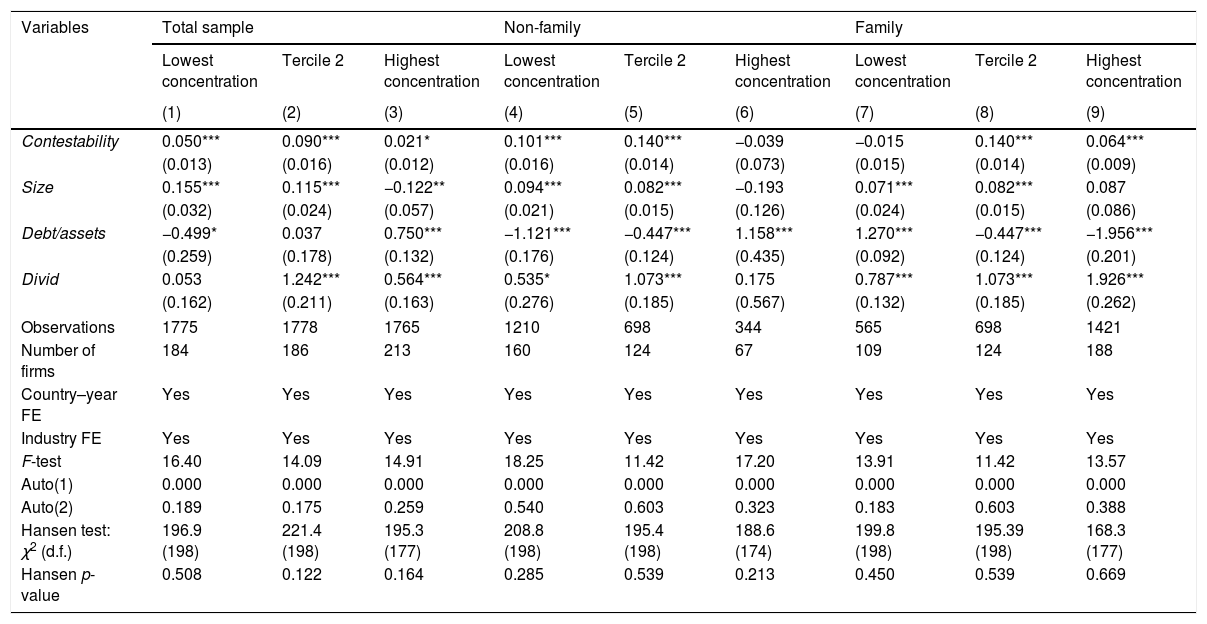

Contestability of control and firm value – cross-sectional analysis (Tobin's q as dependent var.).

| Variables | Total sample | Non-family | Family | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lowest concentration | Tercile 2 | Highest concentration | Lowest concentration | Tercile 2 | Highest concentration | Lowest concentration | Tercile 2 | Highest concentration | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | |

| Contestability | 0.050*** | 0.090*** | 0.021* | 0.101*** | 0.140*** | −0.039 | −0.015 | 0.140*** | 0.064*** |

| (0.013) | (0.016) | (0.012) | (0.016) | (0.014) | (0.073) | (0.015) | (0.014) | (0.009) | |

| Size | 0.155*** | 0.115*** | −0.122** | 0.094*** | 0.082*** | −0.193 | 0.071*** | 0.082*** | 0.087 |

| (0.032) | (0.024) | (0.057) | (0.021) | (0.015) | (0.126) | (0.024) | (0.015) | (0.086) | |

| Debt/assets | −0.499* | 0.037 | 0.750*** | −1.121*** | −0.447*** | 1.158*** | 1.270*** | −0.447*** | −1.956*** |

| (0.259) | (0.178) | (0.132) | (0.176) | (0.124) | (0.435) | (0.092) | (0.124) | (0.201) | |

| Divid | 0.053 | 1.242*** | 0.564*** | 0.535* | 1.073*** | 0.175 | 0.787*** | 1.073*** | 1.926*** |

| (0.162) | (0.211) | (0.163) | (0.276) | (0.185) | (0.567) | (0.132) | (0.185) | (0.262) | |

| Observations | 1775 | 1778 | 1765 | 1210 | 698 | 344 | 565 | 698 | 1421 |

| Number of firms | 184 | 186 | 213 | 160 | 124 | 67 | 109 | 124 | 188 |

| Country–year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| F-test | 16.40 | 14.09 | 14.91 | 18.25 | 11.42 | 17.20 | 13.91 | 11.42 | 13.57 |

| Auto(1) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Auto(2) | 0.189 | 0.175 | 0.259 | 0.540 | 0.603 | 0.323 | 0.183 | 0.603 | 0.388 |

| Hansen test: χ2 (d.f.) | 196.9 (198) | 221.4 (198) | 195.3 (177) | 208.8 (198) | 195.4 (198) | 188.6 (174) | 199.8 (198) | 195.39 (198) | 168.3 (177) |

| Hansen p-value | 0.508 | 0.122 | 0.164 | 0.285 | 0.539 | 0.213 | 0.450 | 0.539 | 0.669 |

Estimated coefficients (robust standard errors clustered at firm level) from the GMM panel data regressions of Eq. (1) for total sample and subsamples for family and non-family definition. To exploit heterogeneity, we split the sample by thirds of percentage of voting rights in the hands of the largest shareholder. Columns entitled “Tercile 1” represent lower levels of voting rights of the largest shareholders, “Tercile 2” represent medium levels of voting rights of the largest shareholders, and “Tercile 3” represent high levels of voting rights of the largest shareholders (the largest shareholder exceeds the threshold to secure control of the firm). Our dependent variables are: Q TOBi, that is Tobin's q. Contestabilityi,c,t represents the contestability variable. The independent variables are defined in Table 1. We include fixed effects at the firm level (fi), country level (Cc) and year level (qt).

In order to exploit heterogeneity across ownership concentration, Table 7 replicates the baseline model estimations of Eq. (1), but splitting the sample by terciles of the ownership in hands of the largest shareholder. By doing so, we aim to capture the dynamics of multiple shareholders and to verify different effects depending on ownership concentration. Columns 1–3 show the results of the effect of the contestability variable on firm value without distinguishing between the type of largest shareholder (we call this “total sample”). Columns 4–6 show the results using the subsample of non-family firms, and Columns 7–9 show the results for family firms.

For the total sample, the parameters of contestability in Columns 1–3 are positive and statistically significant. This result suggests that a balanced distribution of power is important at all levels of ownership concentration and results in a premium on firm value. Consequently, power distribution seems to alleviate the two types of agency problems. On the one hand, when ownership is relatively widespread (agency problem Type I), the existence of multiple large shareholders increases stockholder involvement and reduces informational asymmetries by applying corporate governance mechanisms such as “the voice” or “the threat of exit”. In contrast, when ownership concentration is high (agency problem Type II), our results suggest that the existence of other large shareholders might improve monitoring activities over the controlling shareholder, positively impacting on the firm's value.

In Columns 4–9 of Table 6, our results suggest that the importance of contestability differs between non-family firms and family firms conditional upon ownership concentration. In non-family firms, Columns 4 and 5 show that the coefficient of the contestability variable is positive and statistically significant for the groups of firms with the lowest ownership concentration. In turn, we can say that contestability is only important under conditions in which the fraction of shares owned by the largest non-family shareholder is not very high. In other words, the power distribution in non-family firms alleviates agency problems related to the vertical dimension of corporate governance (manager–shareholder conflict).

In contrast, results in Columns 7–9 of Table 6 suggest that the existence of multiple large shareholders alleviates the conflicts related to higher levels of ownership concentration in family firms. In fact, Column 7 shows that contestability is not statistically significant, while Columns 8 and 9 show that contestability is positive and statistically significant for middle (Tercile 2) and high levels of shares owned by the largest family shareholder. According to these estimates, the market gives a premium on firm value because of better oversight of the first family shareholder.

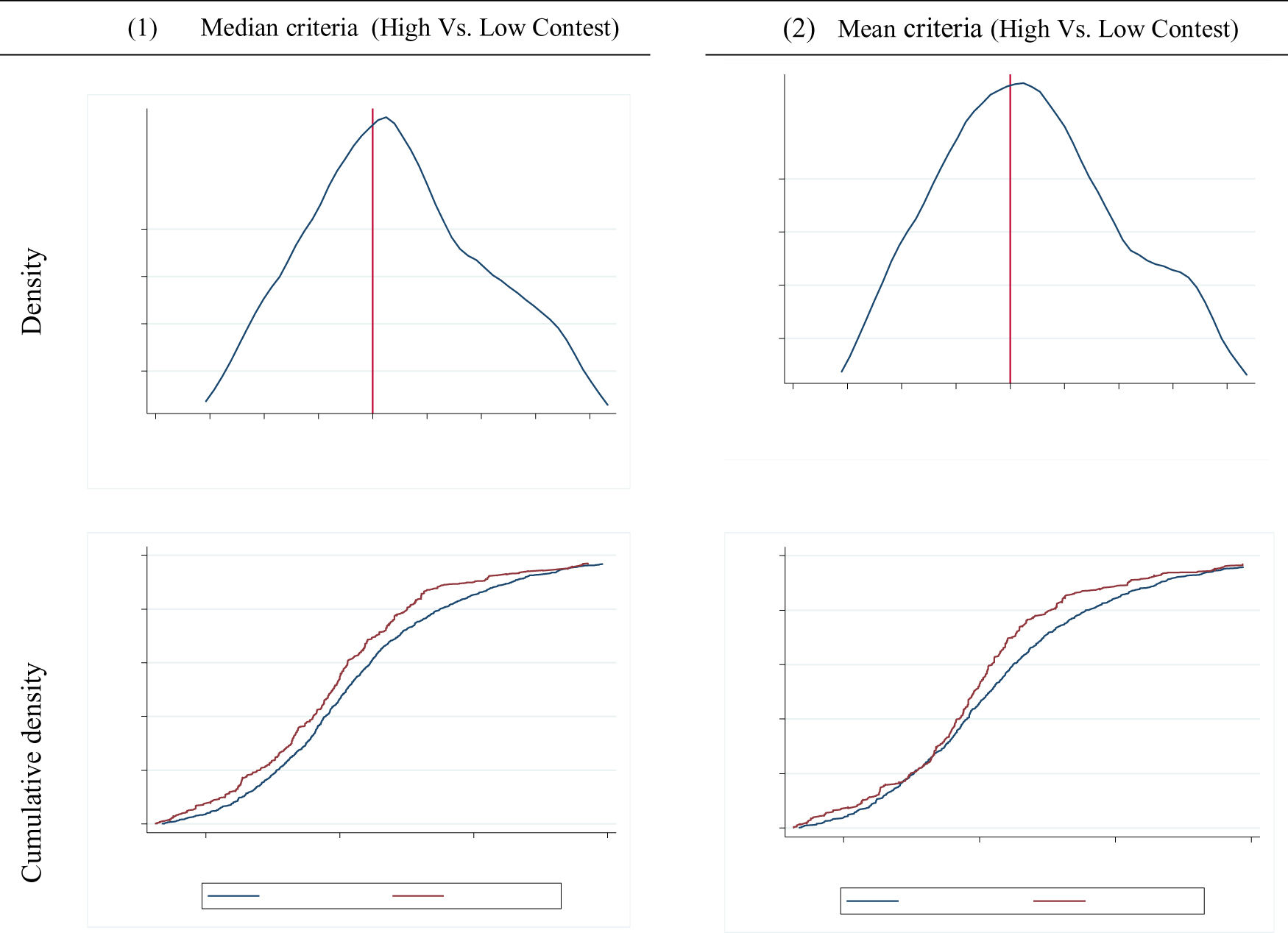

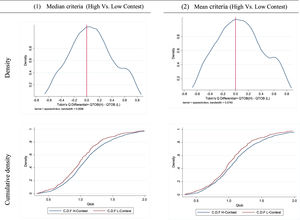

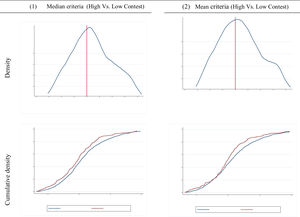

Additional robustness check: nearest-neighbour matchingWe estimate three nearest-neighbour matching (NN-match) analyses. NN-match methodology is commonly used to mitigate selection bias (Heckman et al., 1998), and has been implemented in finance literature (Bharath et al., 2011; Villalonga, 2004). In our case, we match two firms that belong to the same country, industry, and year and that are also similar in size, debt structure, and fraction of shares held by the largest shareholder, but display differing levels of contestability. We then analyse the existence of differences in firm valuation. In the first analysis, the treatment is higher vs. lower levels of contestability using the median criteria. The second treatment is higher vs. lower levels of contestability using the mean criteria. Finally, we replicate the analysis in family owned firms with both median and mean criteria. In the matching estimation, we use Tobin's q as the dependent variable and we control for P1, Size, and Debt/Assets in order to choose the nearest match. We also ensure that the exact match considers industry, country, and year.7

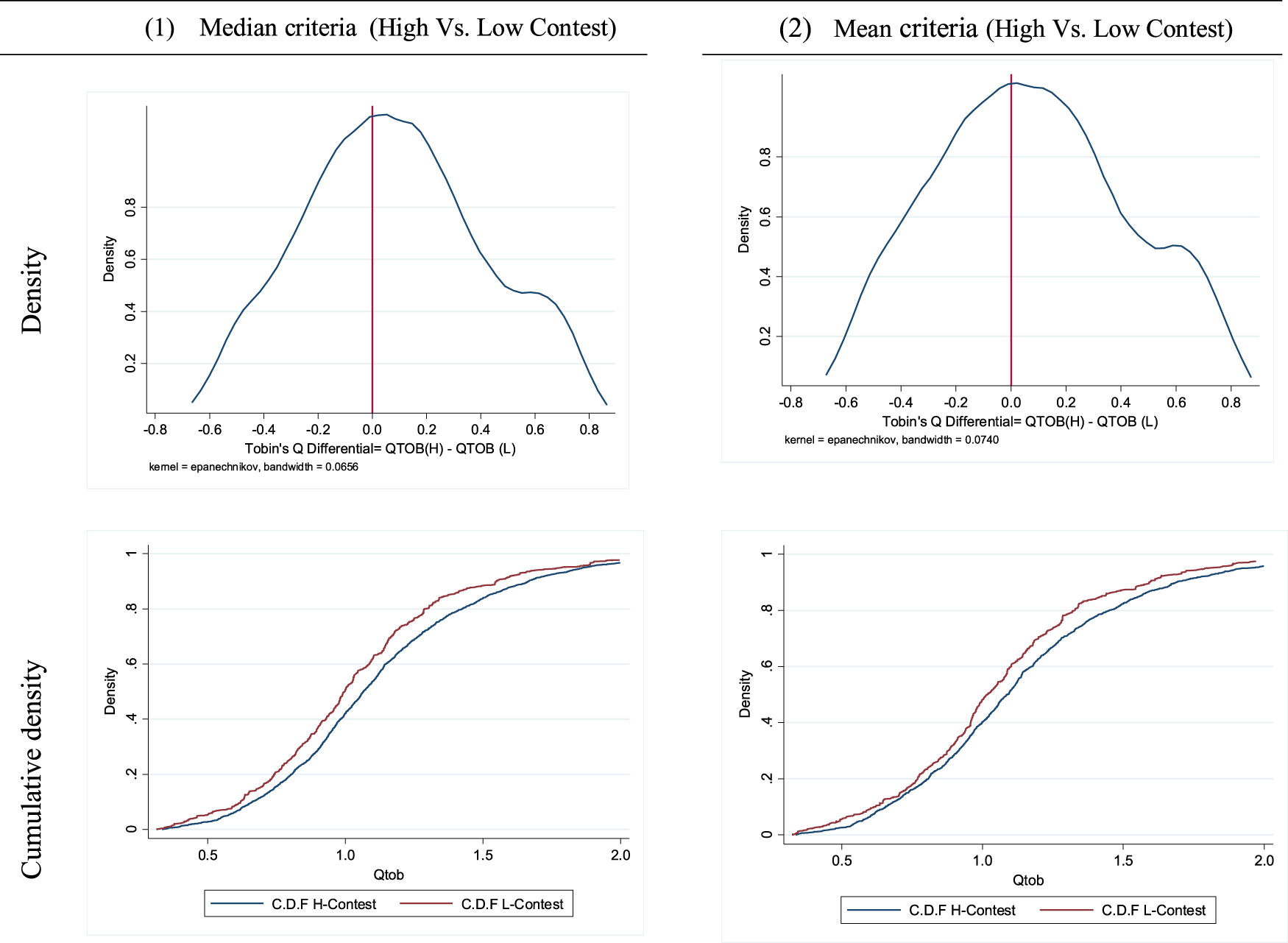

Fig. 1 reports the results for the total sample, whereas Fig. 2 focuses only on family owned firms. Using two subsamples, in Columns 1 and 2 of Fig. 1 we match firms and compare them face-to-face. The splitting criteria used are firms that contest control over the median value (higher contestability values) vs. firms with contestability values below the median. In Column 2 of Fig. 1, we provide analogous comparisons when high and low contesting levels are defined in terms of the mean contestability value (country–year).

Kernel density estimate and cumulative distribution function for Tobin's q differential depending on contestability after nearest neighbour matching. Notes: results of nearest-neighbour matching between high and low contestability firms after controlling for firm size, leverage, voting rights of the main shareholder and debt maturity (exact matching in year, country and Thomson Reuters economic classification for industrial sector). The matched samples were bounded to the Qtob differential between −15% and 15%, resulting in a paired sample of 1796 and 1292 for the median and mean criteria, respectively. The Epanechnikov kernel function was used to estimate the density function. The two-sample Kolmogorov–Smirnov test for equality of distribution functions was performed. The result for the median criteria (first column) indicates that the biggest difference between firms with high contestability (c.d.f H-Contest) and low contestability (c.d.f L-Contest) is 0.0834 (p-value 0.000), the biggest difference between the c.d.f L-Contest and the c.d.f H-Contest is −0.0134 (p-value 0.755) and the combined test has a p-value of 0.000. The result for the mean (second column) criteria indicates that the biggest difference between firms with high contestability (c.d.f H-Contest) and low contestability (c.d.f L-Contest) is 0.094 (p-value 0.000), the biggest difference between the c.d.f L-Contest and the c.d.f H-Contest is −0.032 (p-value 0.987) and the combined test has a p-value of 0.000.

Kernel density estimate and cumulative distribution function for Tobin's q differential after nearest neighbour matching in family firms. Notes: results of nearest-neighbour matching between high and low contestability firms after controlling for firm size, leverage, voting rights of the main shareholder and debt maturity (exact matching in year, country and Thomson Reuters economic classification for industrial sector). The matched samples were bounded to the Qtob differential between −15% and 15%, resulting in a paired sample of 1003 and 693 for the median and mean criteria, respectively. The Epanechnikov kernel function was used to estimate the density function. The two-sample Kolmogorov–Smirnov test for equality of distribution functions was performed. The result for the median criteria (first row) indicates that the biggest difference between firms with high contestability (c.d.f H-Contest) and low contestability (c.d.f L-Contest) is 0.0779 (p-value 0.000), the biggest difference between the c.d.f L-Contest and the c.d.f H-Contest is −0.0182 (p-value 0.458) and the combined test has a p-value of 0.000. The result for the mean (second row) criteria indicates that the biggest difference between firms with high contestability (c.d.f H-Contest) and low contestability (c.d.f L-Contest) is 0.081 (p-value 0.000), the biggest difference between the c.d.f L-Contest and the c.d.f H-Contest is −0.0214 (p-value 0.987) and the combined test has a p-value of 0.000.

In the first row of Fig. 1, we plot the distribution of the difference in valuation between the treated group (higher contestability) and the control group (lower contestability). For the first column (the upper left-hand side graph) we see that the estimated effect (the density function) is positive. The results of NN-matching seem to suggest the existence of a contestability premium on performance, and the centre of the kernel distribution shows a positive QTOB difference of around 0.086. In the second row, we also present the cumulative density distribution for the two subsamples. The lower left-hand side graph shows a clear stochastic dominance in performance for the subsample of higher contestability of control. In the second column of Fig. 1, we estimate a similar analysis using the mean (rather than the median) as a splitting criterion. For the two right-hand side graphs, we observe a clear premium in performance and a first order stochastic dominance on performance (QTOB) for the subsample of firms with high contestability, with the maximum difference in Tobin's q being around 0.123.

In Fig. 2, we run a similar analysis focusing only on family owned firms. The first row shows a premium on firm value for the higher contestability subsample of around 0.054 (Column a) and 0.075 (Column b) using the median and the mean criteria, respectively. The cumulative distribution (lower row) also shows a clear stochastic dominance in value for the group with higher contestability of control. Briefly, the NN-match confirms that higher levels of contestability are positively related to firm performance, with this relationship holding true particularly among family-owned firms.

ConclusionsWe analyse the effect of the existence and the interaction of multiple large, non-related shareholders on firm value for a sample of non-financial listed companies from Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru. Latin America provides a good opportunity to study the interaction among several large shareholders given the weaker legal setting and the concentrated ownership structure that most firms in these countries exhibit. We posit that other large shareholders, other than the controlling one, play an important governance role by preventing the controlling shareholder from expropriating wealth. This role is particularly important in family owned firms and in countries with poorer quality institutions.

Consistent with previous research, our results support the relevance of contestability on firm value. More importantly, although contestability is important in all firms, it plays an even more decisive role in family-owned firms given their particular governance structures. We also find that a more protective legal environment attenuates the relevance of contesting control.

Given the complex relations among shareholders in family firms, our results bear out the importance of balanced ownership structures in order to simultaneously avoid the problems of both too much concentration and of too widespread a dispersion, creating a more favourable scenario to increase the value of these firms.

Our paper offers some policy implications for regulators and supervisory authorities. We identify certain ownership structure issues that raise concerns regarding the interests of minority shareholders. The current debate in Latin America surrounding what constitutes correct corporate governance should consider the inherent problems of ownership structures that are either too concentrated or too dispersed. Balanced ownership structures with several large shareholders seem to achieve an optimal distribution of power within firms. The new codes of good governance being issued in several countries might be advised to consider this. At the same time, our research also encourages policymakers to go on improving the institutional environment so as to achieve enhanced protection of investors’ rights.

A number of directions emerge for future research. We focus on ownership structure as the main power factor in firms. However, some control-enhancing mechanisms (i.e., shareholder coalitions, pyramidal structures, dual-class shares, etc.) allow controlling shareholders to secure control with lower fractions of shares. Joint analysis of such mechanisms might provide valuable insights. Another interesting field of research is the interaction between ownership structure and other corporate governance mechanisms such as the board of directors. Power distribution within the firm is crucially related to board of director dynamics. Thus, the presence of certain directors who represent institutional investors, or banks, or of independent directors who are tasked with defending minority shareholder interests may have influential consequences for the corporate governance of firms in Latin America, or other emerging regions around the world. Additionally, examining dominant shareholder identity might also provide interesting insights.

The authors are grateful to Yama Temouri (editor), Ryan Mcway Allison Kittleson, Philip Jaggs, and to two anonymous referees for their comments on previous versions of the paper. We also thank the support of the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (grant ECO2017-84864-P). All the remaining errors are the authors’ sole responsibility.

Following previous studies (Maury and Pajuste, 2005; Nagar et al., 2011), we compute contestability as the voting power of the secondary largest shareholders (second, third and fourth largest shareholders) over the voting power of the first largest shareholder. Given the ownership features of the Latin American corporate environment (e.g., pyramidal ownership, dual class shares, business groups, blockholders from the same family, among others), it is crucial to know the identity of each shareholder in order to correctly compute their effective voting power. For instance, in a firm the first, second and third shareholder may be the same (shareholder) since the largest shareholder may control the firm indirectly through pyramidal control or may belong to the same family group. We take great care when dealing with these problems.

These control-enhancing mechanisms are typically dual-class stocks, pyramidal ownership structures, family tie shields, and business groups (Ben-Nasr et al., 2015; Levy, 2009; Masulis et al., 2011; Villalonga and Amit, 2010).

In order to correctly analyse the database, we excluded all financial firms, companies with negative equity, and those which are state-owned.

HERF1 is estimated as [P1−P2]2+[P2−P3]2+[P3−P4]2, and HERF2 is estimated as P12+P22+P32+P32.

Roodman (2008) provides a thorough overview of the difference and system estimator GMM techniques.

Results are very similar when using the Market-to-Book ratio as the dependent variable (Columns 4 and 5) and ROA (Columns 7 and 8).

We follow the Rosenbaum and Rubin (1985) standardised bias method. Although we do not report the test of means differences between the control and the treated group, the results are available from the authors upon request.