Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the most frequent neoplasm in the head and neck and in oral sites. Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) is the sixth most common solid cancer, affecting more than 900,000 people worldwide each year. Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) is the largest subgroup of HNSCC and causes 7400 deaths in the United States every year.1 Because of the high prevalence and aggressiveness, HNSCC has been studied by several molecular and cytogenetic techniques. Frequent chromosomal imbalances reported in HNSCC are 3p, 4, 5q, 8p, 9p, 11, 13q, and 18q (losses) and 3q25–26, 5p, 8q24, 9q22–34, 11q13, 14q24, 16p, 19p, 20q24, and 22q (gains).1

The carcinomatous component of carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma (CXPA) encompasses a variety of histological tumor types, such as adenocarcinoma, myoepithelial carcinoma, epithelial–myoepithelial carcinoma, sarcomatoid carcinoma, and salivary duct carcinoma.2 Many epidemiological studies about incidence of CXPA showed few or no cases with an SCC component.

Despite reports of numerous chromosomal alterations in SCC from other sites, no particular chromosomal imbalances have been described for squamous cell carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma (SCC-CXPA). The aim of this study was to identify chromosomal changes associated with SCC-CXPA, comparing with HNSCC data from the literature.

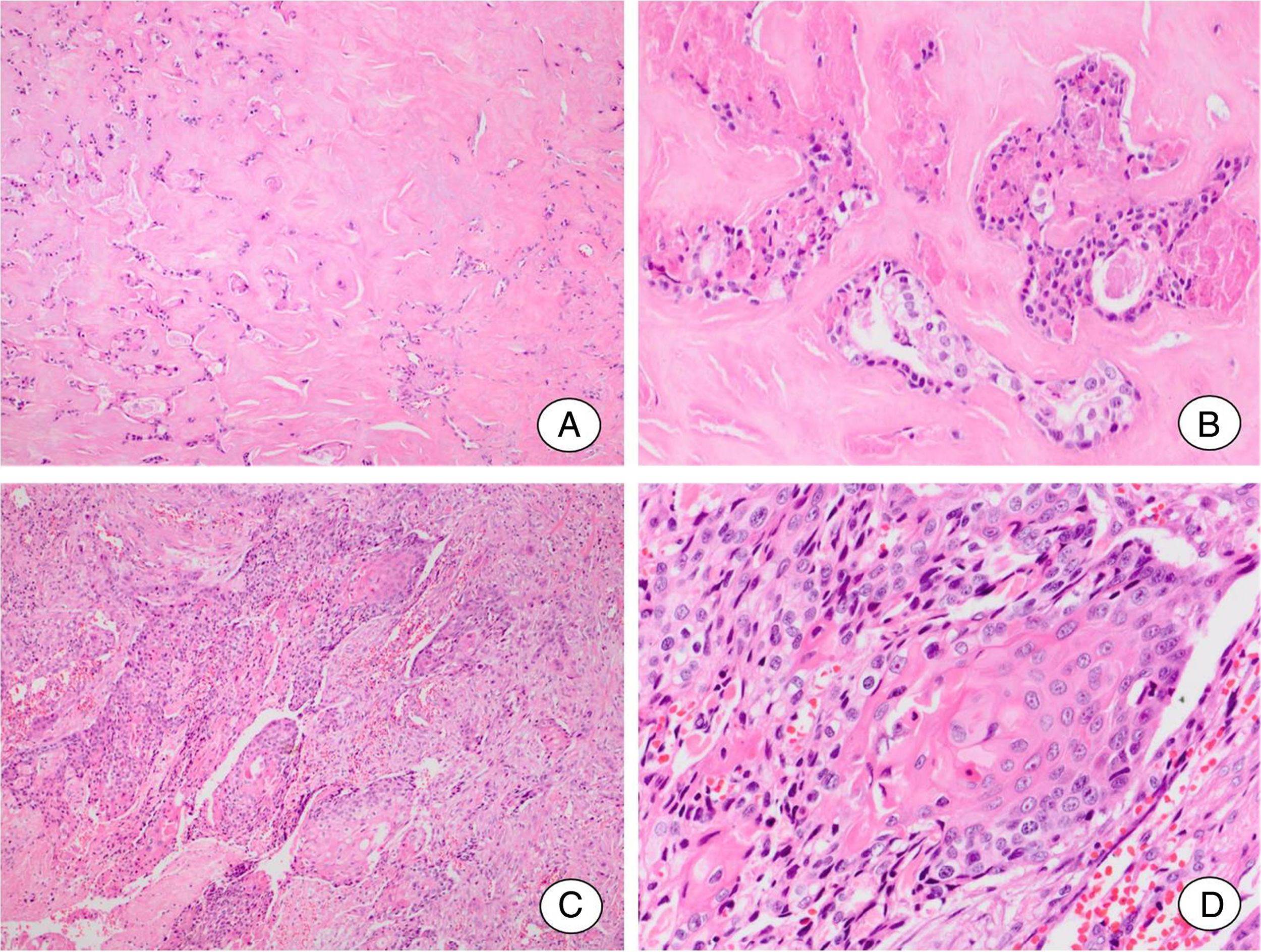

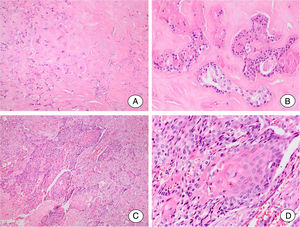

Case reportClinicopathologic dataThe case was referred to this department for histopathological review. The gender and age are unknown. The patient presented a mass of the parotid gland that had been noticeable for ten years. The tumor was excised and histological examination showed pleomorphic adenoma (PA) areas and SCC arising in PA (Fig. 1). Tumor cells presented keratin pearl formation and invaded the adjacent tissues of parotid gland. The neoplasm was classified as a frankly invasive SCC-CXPA. The patient developed distant metastasis in the lungs but the follow-up information was not available.

Squamous cell carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma. (A, B) Residual pleomorphic adenoma. (A) Pleomorphic adenoma area shows extensive hyalinization of the stroma. (B) Few ductal structures lined by cells without atypical features can be seen. (C, D) Carcinomatous component. (C) A frankly invasive squamous cell carcinoma is the malignant component of the tumor. (D) Detail of the malignant component showing islands formed by cells with squamous differentiation.

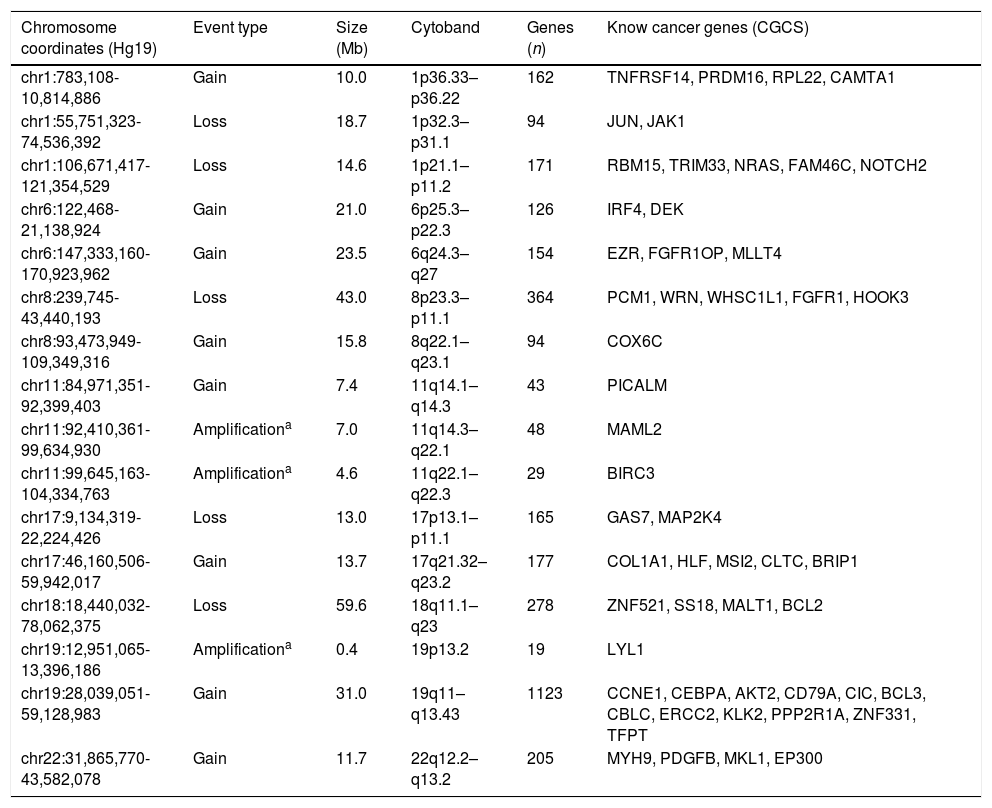

Somatic copy number alterations detected in the SCC-CXPA sample are detailed in Table 1 as well as affected known cancer genes according to the Sanger Cancer Gene Census (https://www.sanger.ac.uk/research/projects/cancergenome/census.html).

Somatic copy number alterations detected by array comparative genomic hybridization in one squamous cell carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma case.

| Chromosome coordinates (Hg19) | Event type | Size (Mb) | Cytoband | Genes (n) | Know cancer genes (CGCS) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| chr1:783,108-10,814,886 | Gain | 10.0 | 1p36.33–p36.22 | 162 | TNFRSF14, PRDM16, RPL22, CAMTA1 |

| chr1:55,751,323-74,536,392 | Loss | 18.7 | 1p32.3–p31.1 | 94 | JUN, JAK1 |

| chr1:106,671,417-121,354,529 | Loss | 14.6 | 1p21.1–p11.2 | 171 | RBM15, TRIM33, NRAS, FAM46C, NOTCH2 |

| chr6:122,468-21,138,924 | Gain | 21.0 | 6p25.3–p22.3 | 126 | IRF4, DEK |

| chr6:147,333,160-170,923,962 | Gain | 23.5 | 6q24.3–q27 | 154 | EZR, FGFR1OP, MLLT4 |

| chr8:239,745-43,440,193 | Loss | 43.0 | 8p23.3–p11.1 | 364 | PCM1, WRN, WHSC1L1, FGFR1, HOOK3 |

| chr8:93,473,949-109,349,316 | Gain | 15.8 | 8q22.1–q23.1 | 94 | COX6C |

| chr11:84,971,351-92,399,403 | Gain | 7.4 | 11q14.1–q14.3 | 43 | PICALM |

| chr11:92,410,361-99,634,930 | Amplificationa | 7.0 | 11q14.3–q22.1 | 48 | MAML2 |

| chr11:99,645,163-104,334,763 | Amplificationa | 4.6 | 11q22.1–q22.3 | 29 | BIRC3 |

| chr17:9,134,319-22,224,426 | Loss | 13.0 | 17p13.1–p11.1 | 165 | GAS7, MAP2K4 |

| chr17:46,160,506-59,942,017 | Gain | 13.7 | 17q21.32–q23.2 | 177 | COL1A1, HLF, MSI2, CLTC, BRIP1 |

| chr18:18,440,032-78,062,375 | Loss | 59.6 | 18q11.1–q23 | 278 | ZNF521, SS18, MALT1, BCL2 |

| chr19:12,951,065-13,396,186 | Amplificationa | 0.4 | 19p13.2 | 19 | LYL1 |

| chr19:28,039,051-59,128,983 | Gain | 31.0 | 19q11–q13.43 | 1123 | CCNE1, CEBPA, AKT2, CD79A, CIC, BCL3, CBLC, ERCC2, KLK2, PPP2R1A, ZNF331, TFPT |

| chr22:31,865,770-43,582,078 | Gain | 11.7 | 22q12.2–q13.2 | 205 | MYH9, PDGFB, MKL1, EP300 |

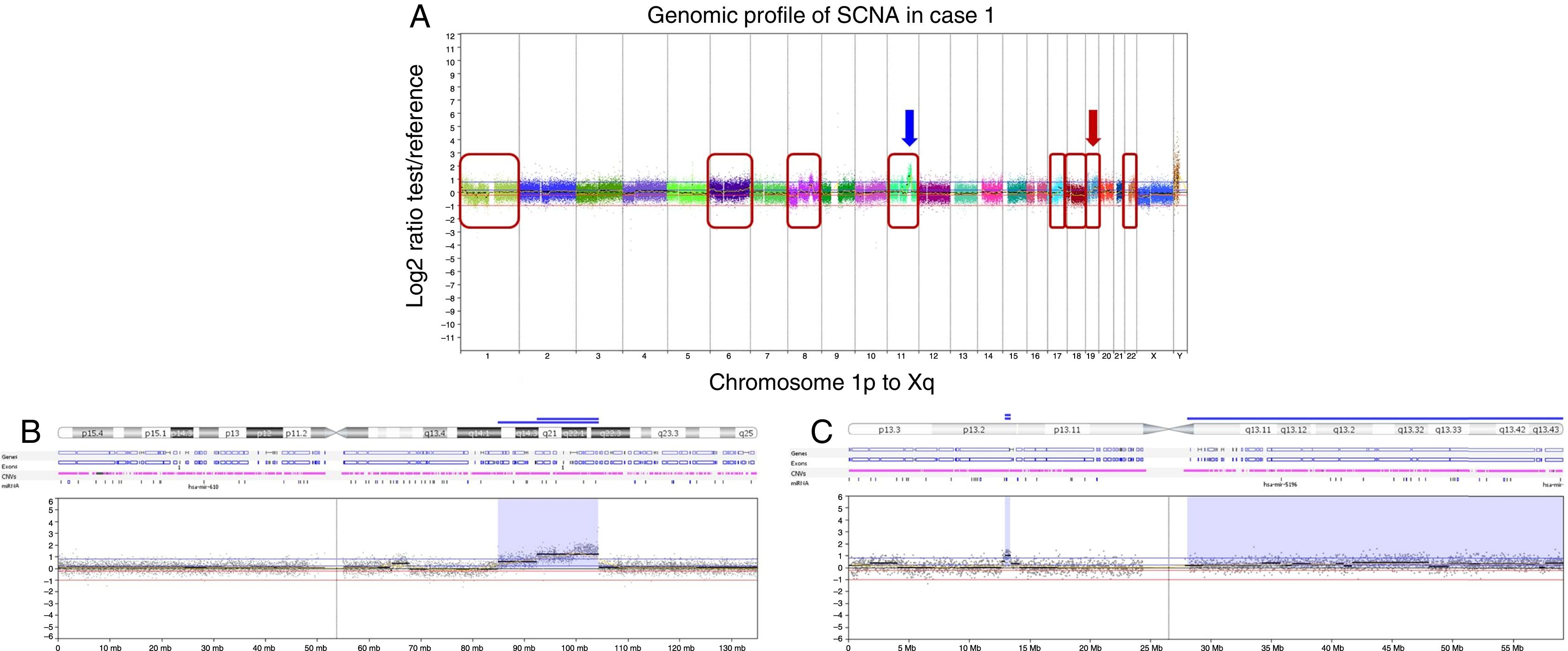

The current case exhibited a complex genomic pattern with several copy number alterations. Losses were detected at 1p, 8p, 17p, and 18q, and gains were identified at 1p, 6, 8q, 11q, 17q, 19q, and 22q (Fig. 2A).

Copy number alterations detected by array comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) in the squamous cell carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma case. (A) Array-CGH genomic profile exhibiting the all the identified copy number alterations of this case. The x-axis represents probes ordered according to their genomic position from chromosomes 1p to Xq (each chromosome is labeled with a different color). The y-axis denotes the log2 test/reference values (genomic gains and losses are plotted above or below the 0 baseline, respectively; images adapted from the software Nexus Copy Number 7.0, Biodiscovery). The red box indicates chromosomes that harbor genomic rearrangements of losses or gains: 1, 6, 8, 11, 17, 18, 19 and 22. The arrows show the regions of genomic amplifications at chromosomes 11 and 19. (B) Array-CGH profile of the chromosome 11 showing in detail the two regions with high copy number gain (amplifications): at 11q14q22.1 (7 Mb) and at 11q22.1-q22.3 (4.6 Mb) (blue arrow in A). (C) Array-CGH profile of the chromosome 19 exhibiting one region of genomic amplification at 19p13.2 (0.4 Mb) (red arrow in A).

Three regions exhibiting high copy number alterations (amplifications) were detected at 11q14.3q22.1, 11q22.1q22.3 (Fig. 2B), and 19p13.2 (Fig. 2C). Among other genes, these amplifications encompass the known cancer genes MAML2, BIRC3, and LYL1.

DiscussionMariano et al.2 reported one SCC-CXPA out of 38 cases (2.6%) of CXPA from a Brazilian population. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, only sporadic cases were described showing SCC as the malignant component of CXPA, emphasizing the clinical and morphological features.

SCC originates from the epithelial component of the PA, and in lesions that arise from minor salivary glands, it is important to demonstrate no continuity of the SCC nests with the buccal mucosa. In the current case, areas of residual PA were associated with a widely invasive SCC in the soft tissues surrounding the parotid gland. Distant metastases were observed in this case, suggesting that SCC belongs to the group of aggressive CXPAs. It has been proposed that CXPA is actually a category of tumors rather than a single tumor type, since both aggressive and indolent carcinomas can arise from a PA.

Local aggressiveness, high rate of early relapse tumors, and reduced five-year survival rates not exceeding 50% are typical clinical features of SCC. OSCC causes 7400 deaths in the USA every year.1 For these reasons, during the last two decades, genome screening approaches like chromosomal CGH were applied to disclose the molecular basis of carcinogenesis of this tumor.

A complex genomic profile of the copy number alterations of HNSCC has been described in the literature, including 3p, 4, 5q, 8p, 9p, 11, 13q, and 18q losses, and 3q25q26, 5p, 8q24, 9q22q34, 11q13, 14q24, 16p, 19q, 20q24, and 22q gains.1 The current case also shows a complex genomic profile with several copy number alterations, but with a different pattern compared to SCC from head and neck, probably due to distinct cellular lineage. Interestingly, in HNSCC there are multiple discrete regions of loss at 3p.1,3 Even though cytogenetic investigations have suggested that 3p loss is a key genomic change in HNSCC, the present case did not show this alteration. However, some similarities between HNSCC and this case were found, such as 8p23 and 18q11 losses, and 8q22.1, 19q, and 22q gains. These alterations can be specific to squamous cell differentiation and contribute to aggressive behavior.3

It has been suggested that in HNSCC, gains on 3q26 and 11q13 and deletions on 8p23 and 22q could be valuable markers of aggressive disease.1 The loss at 8p23 in the current case encompasses important cancer-related genes, such as PCM1, WRN, WHSCILI, FGFR1, and HOOK3. However, chromosomal gains on 1q and 16q as well as chromosomal loss on 18q have been suggested to represent prognostic markers in HNSCC.1,3 The present report also found loss at 18q involving the cancer related genes ZNF521, SS18, MALT1, and BCL2. A gain at 8q22.1q23.1 was also observed. In this genomic interval, the YWHAZ gene is mapped, a HNSCC proto-oncogene candidate.

New findings not previously reported for HNSCC were also identified, such as losses at 1p32, 1p21, and 17p13.1, as well as gains at 1p36.33, 6p25.3, 6q24, 11q14, and 17q21.32. The 1p32 loss is associated with the development of adenoid cystic carcinoma,1 and 1p36 is frequently deleted in human cancers. Among these regions of imbalance, 1p21.1 loss seems particularly interesting, because it comprises several cancer related genes.1 Overexpression of the DEK gene (6p25.3) is associated with gastric and breast adenocarcinoma,4 as well as the role EZRIN has in colorectal, pancreatic, gastric, and other adenocarcinomas.5

It was noteworthy that three genomic amplifications were detected encompassing the region at 11q14.3q22.1, 11q22.1q22.3, and 19p13.2. These amplifications can harbor relevant genes driving the carcinogenesis, and MAML2, BIRC3, and LYL1 are known cancer genes mapped within these regions.

MAML2 (11q14.3q22.1) (mastermind-like 2) has a role as a transcriptional coactivator for the Notch receptor, and was reported to be rearranged with CRTC1 and CRTC3 in mucoepidermoid carcinomas.6 In the present case, the diagnosis of mucoepidermoid carcinoma arising in PA was ruled out in the histologic examination since the malignant component did not contain mucous cells. MAML2-CRTC1 and MAML2-CRTC3 have not been found in adenosquamous carcinoma, SCC, or any other salivary gland carcinoma.6 MAML2 amplified induces the transcription of the HES-1 gene (a Notch target gene) that regulates the expression of tissue-specific transcription factors that influence lineage and other events. This amplification is described with a low frequency in cancers of several sites, but not in HNSCC.

Another amplified gene, BIRC3 (baculoviral IAP repeat containing 3), encodes a member of the IAP family of proteins that inhibit apoptosis. Amplification involving BIRC3 has been detected in pancreatic cancer, osteosarcoma, acute myeloid leukemia, mammary carcinoma, lung cancer, cervical cancer, and SCC.7 It has been found that BIRC3 may enhance cancer cell survival and cancer progression, suggesting that treatments targeting this gene product may provide useful therapeutic options. LYL1 (lymphoblastic leukemia-associated hematopoiesis regulator 1) gene represents a basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor, which encodes a protein with roles in blood vessel maturation and hematopoiesis.8 It is believed that in salivary gland tumors LYL1 amplification could contribute with oncogenesis.

PA as well as CXPA has been reported to harbor highly specific chromosome abnormalities related to PLAG1 and HMGA2 genes. Rearrangements of these genes (8q12 rearrangements, target gene PLAG1 and 12q14-15 rearrangements, target gene HMGA2) have been implicated in the genesis of PA and CXPA. However, although these chromosome abnormalities are frequent in these tumors, they are not detected in all of them.9 In the current case, amplified PLAG1 or HMGA2 genes were not found, suggesting that the tumor probably belonged to the group without such karyotic alteration.

ConclusionIn summary, SCC-CXPA showed a complex pattern of copy number alterations that has some similarities with that of HSCCN. It is likely that these chromosomal abnormalities may be involved in the development of the squamous phenotype and aggressive behavior of the SCC-CXPA. However, genomic amplifications of known cancer genes, such as LYL1, BIRC3, and MAML2 detected only in SCC-CXPA could have importance for the process of malignant transformation of PA. These latter alterations may represent clinically relevant markers for SCC-CXPA diagnosis.

FundingFAPESP Process Nos. 2011/23204-5 and 2011/23366-5.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Mariano FV, Saccomani LF, Giovanetti K, Del Negro A, Kowalski LP, Krepischi AC, et al. Genomic profile of a squamous cell carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma compared to a head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2018;84:393–7.

Peer Review under the responsibility of Associação Brasileira de Otorrinolaringologia e Cirurgia Cérvico-Facial.