This study highlights the prevalence of aminoglycoside-modifying enzyme genes and virulence determinants among clinical enterococci with high-level aminoglycoside resistance in Inner Mongolia, China. Screening for high-level aminoglycoside resistance against 117 enterococcal clinical isolates was performed using the agar-screening method. Out of the 117 enterococcal isolates, 46 were selected for further detection and determination of the distribution of aminoglycoside-modifying enzyme-encoding genes and virulence determinants using polymerase chain reaction -based methods. Enterococcus faecium and Enterococcus faecalis were identified as the species of greatest clinical importance. The aac(6′)-Ie-aph(2″)-Ia and ant(6′)-Ia genes were found to be the most common aminoglycoside-modifying enzyme genes among high-level gentamicin resistance and high-level streptomycin resistance isolates, respectively. Moreover, gelE was the most common virulence gene among high-level aminoglycoside resistance isolates. Compared to Enterococcus faecium, Enterococcus faecalis harbored multiple virulence determinants. The results further indicated no correlation between aminoglycoside-modifying enzyme gene profiles and the distribution of virulence genes among the enterococcal isolates with high-level gentamicin resistance or high-level streptomycin resistance evaluated in our study.

Enterococci have emerged as an important source of hospital-acquired infections, including those related to the surgical site, respiratory tract, urinary tract, skin and soft tissue, and bacteremia.1 Several studies have indicated increasing enterococci resistance to a broad range of antimicrobial agents via intrinsic and acquired mechanisms.2 High-level aminoglycoside resistance (HLAR) has been recognized for several decades. Gentamicin and streptomycin are the two main aminoglycosides used in clinical practice. Recently, high-level gentamicin resistance (HLGR) (MIC ≥500μg/ml) and high-level streptomycin resistance (HLSR) (MIC ≥2000μg/ml) have been reported worldwide.3–8 Clinical experience supports the use of aminoglycosides along with cell-wall inhibitors for treating serious enterococcal infections.9 However, high-level resistance of clinical isolates of Enterococcus species to aminoglycosides negates the synergism between cell-wall inhibitors and aminoglycosides, making the treatment of serious enterococcal infections difficult.10

In general, enterococci are intrinsically resistant to clinically achievable concentrations of aminoglycosides. However, high-level resistance to aminoglycosides is primarily due to acquisition of genes encoding aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes (AMEs).11 Over past decades, a great deal of research has been devoted to understanding the mechanisms behind the high-level resistance of enterococci to aminoglycosides. Until now, the following three classes of AMEs have been identified: acetyltransferase (AAC), aminoglycoside phosphotransferase (APH), and aminoglycoside nucleotidyltransferase (ANT).12 The high-level resistance of enterococci to gentamicin is predominantly mediated by aac(6′)-Ie-aph(2″)-Ia, which encodes the bifunctional AME, AAC(6′)-APH(2″).13 Ten years ago, aph(2″)-Ib, aph(2″)-Ic, and aph(2″)-Id were detected as newer AME genes conferring HLGR among enterococci.14–16 Furthermore, HLSR among enterococci is mediated by aph(3′)-IIIa and ant(6′)-Ia encoding for APH(3′) and ANT(6′)-Ia, respectively.3,11

Additionally, the rise of drug-resistant virulent strains of enterococci is a serious problem in the treatment and control of enterococcal infections. The pathogenicity of enterococci is due to the presence of virulence determinants, such as the Enterococcus faecalis (E. faecalis) antigen A (efaA), adhesion of collagen from E. faecalis (ace) and products involved in aggregation (agg), biosynthesis of an extracellular metalloendopeptidase (gelE), biosynthesis of cytolysin (cylA) and immune evasion (esp).17 Previous research has shown that clinical isolates of the Enterococcus species possess distinctive patterns of virulence factors.18

The difficulty in treating enterococcal infections is associated with determinants of virulence and antimicrobial resistance. Therefore, accurate identification of antibiotic susceptibility patterns and virulence determinants is essential for choosing appropriate therapies and means of infection control. The goal of the present study was to investigate the occurrence of HLAR among enterococci in Inner Mongolia, China. Additionally, the prevalence of six AME encoding genes, aac(6′)-Ie-aph(2″)-Ia, aph(2″)-Ib, aph(2″)-Ic, aph(2″)-Id, aph(3′)-IIIa and ant(6′)-Ia, among enterococcal isolates collected from different specimen sources were investigated. Moreover, the presence of virulence determinants, such as efaA, ace, agg, gelE, cylA and esp, was detected.

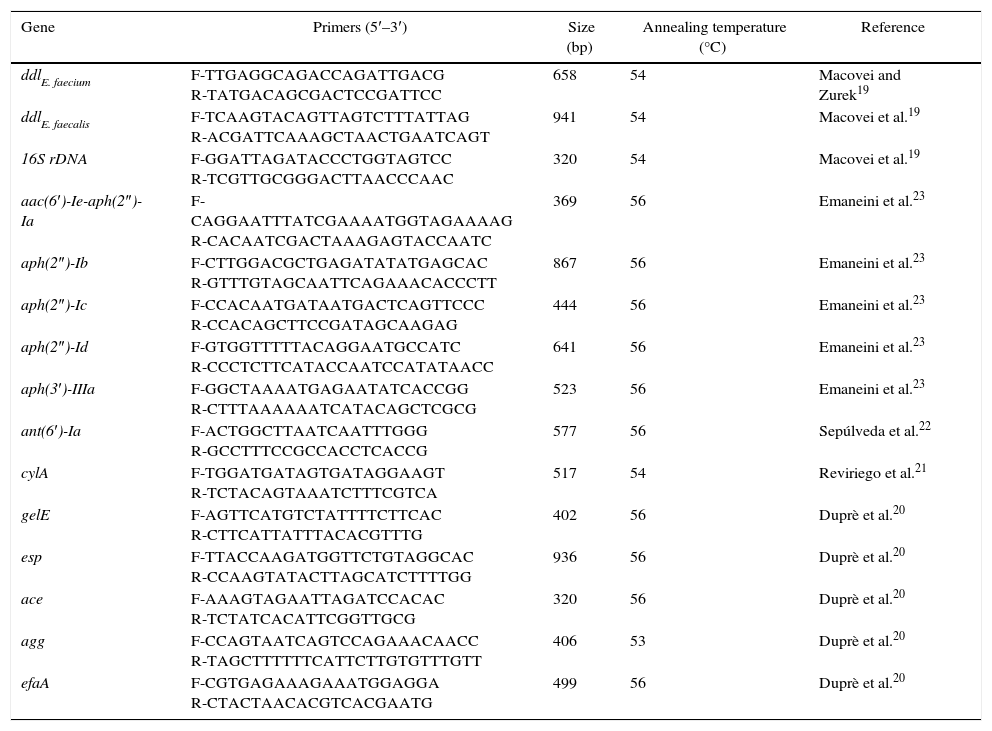

ExperimentalBacterial strains and identificationA total of 117 clinical isolates of enterococci were collected from four hospitals in Inner Mongolia, China, between May 2012 and May 2014. Duplicate isolates were excluded from the study. Institutional ethical clearance was obtained. The isolates were identified as enterococci by conventional biochemical tests and VITEK 2 Compact (BioMérieux, France). Identifications of E. faecalis, E. faecium and the other strains were further confirmed via PCR analysis using ddlE. faecium, ddlE. faecalis and 16S rDNA genes, respectively.19 The isolates were then stored at −80°C. Table 1 shows the primers and the product sizes of all the genes analyzed.19–23

PCR protocols used in this study.

| Gene | Primers (5′–3′) | Size (bp) | Annealing temperature (°C) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ddlE. faecium | F-TTGAGGCAGACCAGATTGACG R-TATGACAGCGACTCCGATTCC | 658 | 54 | Macovei and Zurek19 |

| ddlE. faecalis | F-TCAAGTACAGTTAGTCTTTATTAG R-ACGATTCAAAGCTAACTGAATCAGT | 941 | 54 | Macovei et al.19 |

| 16S rDNA | F-GGATTAGATACCCTGGTAGTCC R-TCGTTGCGGGACTTAACCCAAC | 320 | 54 | Macovei et al.19 |

| aac(6′)-Ie-aph(2″)-Ia | F-CAGGAATTTATCGAAAATGGTAGAAAAG R-CACAATCGACTAAAGAGTACCAATC | 369 | 56 | Emaneini et al.23 |

| aph(2″)-Ib | F-CTTGGACGCTGAGATATATGAGCAC R-GTTTGTAGCAATTCAGAAACACCCTT | 867 | 56 | Emaneini et al.23 |

| aph(2″)-Ic | F-CCACAATGATAATGACTCAGTTCCC R-CCACAGCTTCCGATAGCAAGAG | 444 | 56 | Emaneini et al.23 |

| aph(2″)-Id | F-GTGGTTTTTACAGGAATGCCATC R-CCCTCTTCATACCAATCCATATAACC | 641 | 56 | Emaneini et al.23 |

| aph(3′)-IIIa | F-GGCTAAAATGAGAATATCACCGG R-CTTTAAAAAATCATACAGCTCGCG | 523 | 56 | Emaneini et al.23 |

| ant(6′)-Ia | F-ACTGGCTTAATCAATTTGGG R-GCCTTTCCGCCACCTCACCG | 577 | 56 | Sepúlveda et al.22 |

| cylA | F-TGGATGATAGTGATAGGAAGT R-TCTACAGTAAATCTTTCGTCA | 517 | 54 | Reviriego et al.21 |

| gelE | F-AGTTCATGTCTATTTTCTTCAC R-CTTCATTATTTACACGTTTG | 402 | 56 | Duprè et al.20 |

| esp | F-TTACCAAGATGGTTCTGTAGGCAC R-CCAAGTATACTTAGCATCTTTTGG | 936 | 56 | Duprè et al.20 |

| ace | F-AAAGTAGAATTAGATCCACAC R-TCTATCACATTCGGTTGCG | 320 | 56 | Duprè et al.20 |

| agg | F-CCAGTAATCAGTCCAGAAACAACC R-TAGCTTTTTTCATTCTTGTGTTTGTT | 406 | 53 | Duprè et al.20 |

| efaA | F-CGTGAGAAAGAAATGGAGGA R-CTACTAACACGTCACGAATG | 499 | 56 | Duprè et al.20 |

Screening for HLAR was performed using the agar-screening method according to the standards and interpretive criteria described by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI).24 Briefly, brain heart infusion agar containing gentamicin (500μg/ml) and streptomycin (2000μg/ml) was used. Plates were incubated for 24h at 37°C. The aminoglycoside-susceptible strain E. faecalis ATCC 29212 and the aminoglycoside-resistant strain E. fecalis ATCC 51299 were utilized as controls for HLAR detection.

Amplification of AMEs and virulence genesThe total DNA template was extracted from enterococci according to the instruction manuals of commercial DNA extraction kits (Hangzhou BioSci Biotech Co., Ltd, China). A PCR method was used to detect the presence of AME and virulence genes.20–23 The primer couples, product sizes of the genes and annealing temperatures are shown in Table 1. PCR amplification was performed using 1μg of the template DNA, 1μl of each primer (100pmol), and 25μl of 2× PCR master mix (Hangzhou BioSci Biotech Co., Ltd, China) in a total volume of 50μl. A C1000 Touch thermocycler (Bio-Rad, USA) was also employed. PCR conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 94°C for 3min; 35 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 30s, annealing for 30s and elongation at 72°C for 1min, and final extension at 72°C for 5min. PCR products were analyzed by electrophoresis on 1% agarose gel following staining with ethidium bromide.

Statistical analysisAll statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) software (version 11.5). A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results and discussionResultsIdentification of Enterococcus speciesA total of 117 strains of enterococci were isolated from various clinical samples, including urine 48/117 (41.0%), wounds 28/117 (23.9%), bile 18/117 (15.4%), vaginal/semen swabs 6/117 (5.1%), pus 6/117 (5.1%), blood 3/117 (2.6%), sputum 2/117 (1.7%), and others 6/117 (5.1%). The predominant species observed in our study were E. faecium 63/117 (53.8%) and E. faecalis 33/117 (28.2%). We also detected E. avium 11/117 (9.4%), E. gallinarum 6/117 (5.1%), E. casseliflavus 3/117 (2.6%), and E. durans 1/117 (0.9%).

Detection of HLAR in enterococciResistance rates were determined using the agar-screening method. Among the 117 isolates tested, 50/117 (42.7%) were HLGR, and 32/117 (27.4%) were HLSR. A total of 12/117 (10.3%) of our study isolates were both HLGR and HLSR. The highest resistance was observed among E. faecium, followed by E. faecalis and E. avium.

PCR amplification of AME genes in gentamicin-resistant or streptomycin-resistant isolatesOf the 117 enterococcal isolates evaluated, 46 were selected for further detection and determination of distributions of AME encoding genes (Table 2). Of 28 HLGR isolates (Table 2), 25 (89.3%) carried aac(6′)-Ie-aph(2″)-Ia, 2 (7.1%) carried aph(2″)-Ic, 3 (10.7%) carried aph(2″)-Id, and 7 (25.0%) carried aph(3′)-IIIa. However, aph(2″)-Ib was not detected among the isolates evaluated in this study. Some HLGR isolates carried multiple AME genes. Two isolates (7.1%) carried aac(6′)-Ie-aph(2″)-Ia and aph(2″)-Ic; 3 isolates (10.7%) carried aac(6′)-Ie-aph(2″)-Ia and aph(2″)-Id; and 6 isolates (21.4%) carried aac(6′)-Ie-aph(2″)-Ia and aph(3′)-IIIa.

Distributions of aminoglycoside modifying enzyme-encoding genes in enterococci with high-level gentamicin resistance. Some isolates carried multiple aminoglycoside modifying enzyme-encoding genes.

| AME gene | Distribution of high-level gentamicin resistance in enterococci (n=28) | Total no. (%) of isolates | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. faecium (n=19) | E. faecalis (n=7) | E. avium (n=2) | ||

| aac(6′)-Ie-aph(2″)-Ia | 18 | 5 | 2 | 25 (89.3%) |

| aph(2″)-Ib | – | – | – | – |

| aph(2″)-Ic | – | 2 | – | 2 (7.1%) |

| aph(2″)-Id | 2 | – | 1 | 3 (10.7%) |

| aph(3′)-IIIa | 6 | 1 | – | 7 (25.0%) |

| aac(6′)-Ie-aph(2″)-Ia+aph(2″)-Ic | – | 2 | – | 2 (7.1%) |

| aac(6′)-Ie-aph(2″)-Ia+aph(2″)-Id | 2 | – | 1 | 3 (10.7%) |

| aac(6′)-Ie-aph(2″)-Ia+aph(3′)-IIIa | 6 | – | – | 6 (21.4%) |

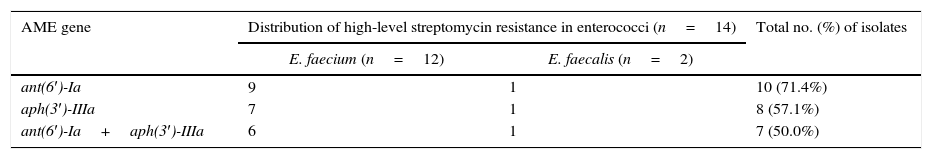

Similarly, of the 14 HLSR isolates identified in our study (Table 3), 10 (71.4%) carried ant(6′)-Ia; 8 (57.1%) carried aph(3′)-IIIa; and 7 (50.0%) carried both ant(6′)-Ia and aph(3′)-IIIa. PCR analysis revealed the absence of resistance genes in susceptible isolates.

Distributions of aminoglycoside modifying enzyme-encoding genes in enterococci with high-level streptomycin resistance. Some isolates carried multiple aminoglycoside modifying enzyme-encoding genes.

| AME gene | Distribution of high-level streptomycin resistance in enterococci (n=14) | Total no. (%) of isolates | |

|---|---|---|---|

| E. faecium (n=12) | E. faecalis (n=2) | ||

| ant(6′)-Ia | 9 | 1 | 10 (71.4%) |

| aph(3′)-IIIa | 7 | 1 | 8 (57.1%) |

| ant(6′)-Ia+aph(3′)-IIIa | 6 | 1 | 7 (50.0%) |

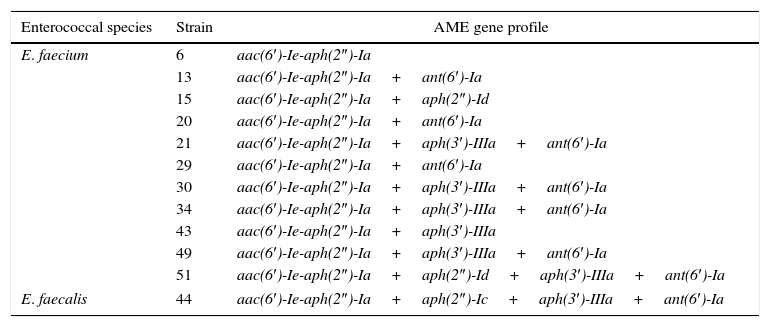

Table 4 shows the AME gene profiles of both HLGR and HLSR isolates. Of the 12 isolates analyzed, all 12 (100%) carried aac(6′)-Ie-aph(2″)-Ia; 9 (75.0%) carried ant(6′)-Ia; 7 (58.3%) carried aph(3′)-IIIa; 2 (16.7%) carried aph(2″)-Id; and 1 (8.3%) carried aph(2″)-Ic. Moreover, 11 isolates (91.7%) carried multiple (two to four) AME genes. Five isolates (41.7%) carried two genes; 4 isolates (33.3%) carried three genes; and 2 isolates (16.7%) carried four genes.

Distributions of aminoglycoside modifying enzyme-encoding genes in enterococci with high-level resistance to both streptomycin and gentamicin.

| Enterococcal species | Strain | AME gene profile |

|---|---|---|

| E. faecium | 6 | aac(6′)-Ie-aph(2″)-Ia |

| 13 | aac(6′)-Ie-aph(2″)-Ia+ant(6′)-Ia | |

| 15 | aac(6′)-Ie-aph(2″)-Ia+aph(2″)-Id | |

| 20 | aac(6′)-Ie-aph(2″)-Ia+ant(6′)-Ia | |

| 21 | aac(6′)-Ie-aph(2″)-Ia+aph(3′)-IIIa+ant(6′)-Ia | |

| 29 | aac(6′)-Ie-aph(2″)-Ia+ant(6′)-Ia | |

| 30 | aac(6′)-Ie-aph(2″)-Ia+aph(3′)-IIIa+ant(6′)-Ia | |

| 34 | aac(6′)-Ie-aph(2″)-Ia+aph(3′)-IIIa+ant(6′)-Ia | |

| 43 | aac(6′)-Ie-aph(2″)-Ia+aph(3′)-IIIa | |

| 49 | aac(6′)-Ie-aph(2″)-Ia+aph(3′)-IIIa+ant(6′)-Ia | |

| 51 | aac(6′)-Ie-aph(2″)-Ia+aph(2″)-Id+aph(3′)-IIIa+ant(6′)-Ia | |

| E. faecalis | 44 | aac(6′)-Ie-aph(2″)-Ia+aph(2″)-Ic+aph(3′)-IIIa+ant(6′)-Ia |

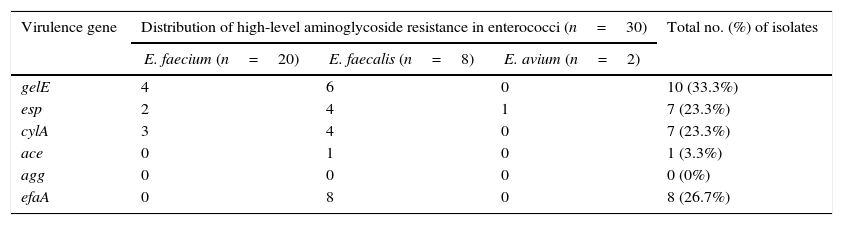

Table 5 shows the presence of virulence genes among HLAR isolates. Of the 30 isolates evaluated, 10 (33.3%) carried gelE; 8 (26.7%) carried efaA; 7 (23.3%) carried esp; 7 (23.3%) carried cylA; and 1 (3.3%) carried ace. The agg gene was not detected in any of isolates. Moreover, AME gene profiles and distributions of virulence determinants were compared among HLGR or HLSR isolates, and no significant correlations were found.

Distributions of virulence genes in enterococci with high-level aminoglycoside resistance.

| Virulence gene | Distribution of high-level aminoglycoside resistance in enterococci (n=30) | Total no. (%) of isolates | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. faecium (n=20) | E. faecalis (n=8) | E. avium (n=2) | ||

| gelE | 4 | 6 | 0 | 10 (33.3%) |

| esp | 2 | 4 | 1 | 7 (23.3%) |

| cylA | 3 | 4 | 0 | 7 (23.3%) |

| ace | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 (3.3%) |

| agg | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 (0%) |

| efaA | 0 | 8 | 0 | 8 (26.7%) |

Enterococci have long been considered one of the most common sources of nosocomial pathogens. The rise of drug-resistant virulent strains of enterococci presents a serious problem with regard to controlling enterococcal infections. Aminoglycoside antibiotics provide efficient therapies for severe enterococcal infections. However, the introduction of two aminoglycoside antibiotics (gentamicin and streptomycin) was followed by the emergence of resistance in enterococci.

To date, several Enterococcus species have been reported, including E. faecium, E. faecalis, E. avium, E. durans, E. gallinarum, E. casseliflavus, E. raffinosus, E. mundtii, E. malodoratus, and E. hirae.25 Similar to previous findings in China,26E. faecium and E. faecalis comprise the predominant conditionally pathogenic bacteria in the present report. Additionally, our antibiotic susceptibility test results identified 42.7% HLGR and 27.4% HLSR clinical isolates, similar to other reports.9 Moreover, in agreement with previous studies,9 HLGR was found to be more common than HLSR in enterococci species.

HLAR is primarily due to the presence of AME genes. HLGR has reportedly been associated with aac(6′)-Ie-aph(2″)-Ia, aph(2″)-Ib, aph(2″)-Ic, aph(2″)-Id, and aph(3′)-IIIa. However, HLSR is mainly mediated by aph(3′)-IIIa and ant(6′)-Ia.3,27 To understand HLAR in enterococci in our region, we investigated the distribution of AME genes among enterococci. As reported in other studies,22,27 our analyses identified aac(6′)-Ie-aph(2″)-Ia and ant(6′)-Ia as the most common AME genes among HLGR and HLSR isolates, respectively. It is noteworthy that some HLAR isolates did not harbor any AME genes. We presume that this phenomenon may be due to the action of other resistance mechanisms. On the other hand, we detected some isolates that co-harbored two, three, or four AME genes simultaneously, consistent with previous studies.28

The distributions of virulence genes among enterococci were further investigated. As reported in other studies,29gelE was identified as the most frequent virulence factor and was more common in E. faecalis than E. faecium. Esp, cylA and ace genes were found in 23.3%, 23.3% and 3.3% of the HLAR isolates, respectively. Recently, Sharifi et al. reported that 52.1% of enterococci from hospitalized patients with urinary tract infections tested positive for the esp gene,30 this value is higher than that determined by the present study. Like previous reports, our findings found that all HLAR E. faecalis isolates harbored efaA.31 However, agg was not detected in any of the enterococci isolates studied herein. Similar to previous studies,32E. faecium and E. faecalis strains showed significantly different patterns with regard to the incidence of virulence determinants. Contrary to E. faecium, E. faecalis harbored multiple virulence genes.

ConclusionsThis study indicates that enterococci recovered from clinical samples in Inner Mongolia, China, contain a variety of AME genes and virulence determinants. The aac(6′)-Ie-aph(2″)-Ia and ant(6′)-Ia genes were the most common AME genes among HLGR and HLSR enterococci, respectively, and gelE was the most frequent virulence determinant.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81460049, No. 81260478), the Natural Science Foundation of Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region of China (No. 2014JQ04, 2015MS0867), the Program for Young Talents of Science and Technology in Universities of the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, and the Science Studies Program in Universities of the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, China (NJZY16211).