Triazole fungicides are used broadly for the control of infectious diseases of both humans and plants. The surge in resistance to triazoles among pathogenic populations is an emergent issue both in agriculture and medicine. The non-rational use of fungicides with site-specific modes of action, such as the triazoles, may increase the risk of antifungal resistance development. In the medical field, the surge of resistant fungal isolates has been related to the intensive and recurrent therapeutic use of a limited number of triazoles for the treatment and prophylaxis of many mycoses. Similarities in the mode of action of triazole fungicides used in these two fields may lead to cross-resistance, thus expanding the spectrum of resistance to multiple fungicides and contributing to the perpetuation of resistant strains in the environment. The emergence of fungicide-resistant isolates of human pathogens has been related to the exposure to fungicides used in agroecosystems. Examples include species of cosmopolitan occurrence, such as Fusarium and Aspergillus, which cause diseases in both plants and humans. This review summarizes the information about the most important triazole fungicides that are largely used in human clinical therapy and agriculture. We aim to discuss the issues related to fungicide resistance and the recommended strategies for preventing the emergence of triazole-resistant fungal populations capable of spreading across environments.

Fungicides are a key component in human therapy and the control of plant diseases caused by fungi that threaten human health and crop production.1–5 Among the several types of fungicides, the azole group (triazole and imidazole derivatives) was first introduced in the 1970s.3 Since then, azoles, especially the triazoles, have been widely used for the control of fungal diseases of several plants and human mycoses.6–8 As opposed to other systemic fungicides, the specific site of action of triazoles is an inherent advantage that has led to improved control efficacy of the target fungus.9,10 However, experience has shown that these compounds are prone to resistance in the pathogenic population, especially without the following of recommended practices that are aimed at prolonging the effectiveness of these fungicides.9,11,12

In this context, the efficacy of triazole fungicides can be affected due to cross-resistance or when an isolate develops resistance to all fungicides in a chemical group.13,14 Some authors have also suggested that cross- and multidrug-resistance may be driving forces in the development of resistance in fungi that are at the interfaces of agroecosystem, domestic, and hospital environments.15,16 For instance, emerging fungi in clinical environments include saprophytic or plant pathogenic fungi that have previously exposed to triazole fungicides and end up spreading into the environment and infecting humans.6,17–19

In this mini review, we summarize key aspects of the triazoles for therapeutic use and discuss the possible link between triazole-resistant clinical isolates and the widespread use of triazole fungicides for the control of fungal diseases, which would have a major impact in agriculture.

Basic aspects and therapeutic use of triazolesThe azole fungicides are of synthetic origin and are characterized by the presence of an aromatic five-membered heterocycle. These include triazoles (two carbon atoms and three nitrogen atoms), imidazoles (three carbon atoms and two nitrogen atoms), and thiazoles (three carbon atoms, one nitrogen atom and one sulfur atom).20 The characteristics of the azole rings, which are distinguished by the number of nitrogen and sulfur atoms, change the physical and chemical properties, toxicity, and therapeutic efficacies of these compounds.21 Therefore, the addition of different substitutes to the pristine 1,2,4-triazole molecule influences its fungicide or fungistatic effect.

Triazoles affect the biosynthesis of ergosterol, a fundamental component of the fungal cell plasma membrane.22 The main target of antifungal azole drugs is lanosterol 14-α demethylase (Erg11 protein), a cytochrome P450 enzyme that is involved in the conversion of lanosterol to 4,4-dimethylcholesta-8(9),14,24-trien-3β-ol. The azole agents link to this enzyme using the aromatic five-membered heterocycle and thereby inhibit the cytochrome P450 catalytic activity.9,23 The absence of ergosterol and the increase of intermediate compounds alter fungal membrane integrity as well as cell morphology, which inhibits fungal growth.24,25

Triazoles are among the most common systemic fungicides used in the control of plant diseases. Triazoles are absorbed and translocated in the plant, where they act preventively (before infection) or curatively (in the presence of symptoms) by affecting germ tube and appressoria formation or haustoria development and/or mycelial growth.26,27 By widening the window of protection beyond protectant fungicides, which act only preventatively and are not translocated, the advantages of triazoles represent a breakthrough in increasing the productivity of various crops affected by fungal diseases.2 Around a third of all fungicides used for the protection of crop yields include triazoles, among which more than 99% are inhibitors of demethylation (DMI).28 However, triazole fungicides are also known to present long-term stability, allowing them to remain active in certain ecological niches, such as soil and water, for several months.2,29

The number of antifungals available in the medical field for the treatment of systemic infections is relatively limited compared to those used for controlling diseases in plants, which is mainly due to problems related to erratic efficacy, drug toxicity, and intrinsic resistance.30 These compounds are usually effective in both topical and prophylactic treatments of invasive fungal infections.31 However, new triazoles that are less toxic to humans and with more specific targets have been investigated.32–34 The first generation of triazoles for human therapy included itraconazole and fluconazole. The second generation is represented by voriconazole and posaconazole, which proved to be less toxic, safer, and with a broader spectrum of activity, including activity against fungi that were resistant to the previous generation.35,36 Presently, isavuconazole, ravuconazole, and albaconazole are being investigated in phase III clinical trials as extended-spectrum triazoles with fungicidal activity against a wide number of clinically important fungi.

Development and monitoring of triazole resistanceThe development of resistance to triazoles as a result of selective pressure by the continued use of regular or sub-regular dosages of fungicide is typically quantitative and expressed by a gradual change in the frequency of resistant isolates.10 The main mechanisms involved have been reviewed and relate to the overexpression of the CYP51 gene due to mutations (insertions or duplications) in the promoter region and an increase in molecular efflux by ABC transporters caused by the overexpression of genes coding for membrane transport.9,37,38 Recently, a study that examined A. fumigatus isolates from a range of clinical environments suggested point mutations of CYP51 and TR34/L98H genomic regions in isolates obtained from patients with long term use of triazole-based therapy for the treatment of chronic aspergillosis.16

A key element in the sustainable use of fungicides is to monitor the sensitivity of the pathogen population to a certain compound.39–41 There are a number of direct and indirect methods recommended for specific fungi that are aimed at estimating the EC50 (effective concentration at which 50% of fungal growth is inhibited) and MIC (minimum inhibitory concentration) values.10,42–45

In the medical field, the surveillance and prevention of resistance to antifungal agents have been subject to many restrictive actions in recent years. More specifically, the FDA (Food and Drug Administration) and the EMA (European Medicines Agency) regulate and approve the use of antimicrobials in North America and Europe, respectively.46 Simultaneously, the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI), together with the Subcommittee on Antifungal Susceptibility Testing (AFST) of the European Committee for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST), publish in vitro test protocols periodically for monitoring fungi sensibility to antifungal agents of clinical and veterinary use. These actions allow for the standardization of parameters for the evaluation of in vitro resistance in the laboratory. However, these actions and protocols do not involve the monitoring of resistance of plant pathogenic fungi, thus challenging the use of antifungal agents in clinical therapy.

In agriculture, the Fungicide Resistance Action Committee (FRAC), a technical group maintained by the industry, provides guidelines for the management of fungicide resistance, such as the need to estimate a baseline resistance level in isolates sampled from the population prior to the commercial use of a fungicide.47 During commercial use, reports of failures in disease control and detection of resistant isolates (those with sensitivity levels lower than the baseline) are indicators of the risk of developing fungicide resistance.47 Periodically, information is provided by the FRAC about the risk of plant pathogens that ranges from low to high. Currently, many studies are known that report steadily increasing resistance to triazoles in plant pathogenic fungi.48

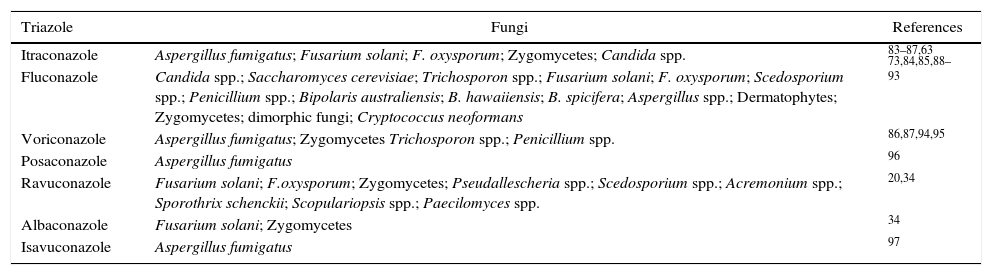

Triazole resistance in clinical isolates and agricultural useIn the medical field, the first report of DMI's resistance in A. fumigatus isolates dates back more than three decades ago. However, the resistance to itraconazole by Aspergillus spp. from the clinical environment was first reported in 1997 for three isolates obtained from California in the late 1980s.49 The prescription of triazoles as a preferential choice for the treatment of patients with respiratory diseases has been considered to contribute to the development of resistance to this group of fungicides.10,50,51 Multidrug-resistance (MDR)52 is considered to be the cause of the failure of a wide range of antifungal agents available on the market.53,54 As an emergent fungus in clinical environments, A. fumigatus holds a history of cross-resistance and multi-resistance to azoles.55 It is probable that millions of people are not effectively treated due to infections by fungi exhibiting antifungal resistance, among which 4.8 million cases are related only to the species of Aspergillus.56 The triazole antifungals commonly used in the medical field for the treatment of fungal diseases and pathogens that have exhibited some level of resistance are listed in Table 1.

Pathogenic fungi with intrinsic or developed resistance to triazoles for human therapeutic use.

| Triazole | Fungi | References |

|---|---|---|

| Itraconazole | Aspergillus fumigatus; Fusarium solani; F. oxysporum; Zygomycetes; Candida spp. | 83–87,63 |

| Fluconazole | Candida spp.; Saccharomyces cerevisiae; Trichosporon spp.; Fusarium solani; F. oxysporum; Scedosporium spp.; Penicillium spp.; Bipolaris australiensis; B. hawaiiensis; B. spicifera; Aspergillus spp.; Dermatophytes; Zygomycetes; dimorphic fungi; Cryptococcus neoformans | 73,84,85,88–93 |

| Voriconazole | Aspergillus fumigatus; Zygomycetes Trichosporon spp.; Penicillium spp. | 86,87,94,95 |

| Posaconazole | Aspergillus fumigatus | 96 |

| Ravuconazole | Fusarium solani; F.oxysporum; Zygomycetes; Pseudallescheria spp.; Scedosporium spp.; Acremonium spp.; Sporothrix schenckii; Scopulariopsis spp.; Paecilomyces spp. | 20,34 |

| Albaconazole | Fusarium solani; Zygomycetes | 34 |

| Isavuconazole | Aspergillus fumigatus | 97 |

It has been shown that exposure of environmental fungi to triazole fungicides may cause shifts from susceptible to resistant populations, especially in the absence of adaptive costs which may facilitate the spread of resistant populations into diverse environments.57 The surge of “emerging fungi” in the medical field or fungi that are otherwise harmless to humans, such as the zygomycetes and other hyaline filamentous fungi,2,57 has led some authors to hypothesize that other mechanisms may be leading to resistance, such as the large amount of fungicides used in agroecosystems.7,58,59 This hypothesis was initially suggested by studies conducted in the Netherlands13 and later corroborated by studies conducted in Spain,60 Belgium,13 Norway,13 Great Britain,61 Denmark,62 France,63 China,64 Italy,65 Austria,65 and India.28

A few studies have jointly examined the sensitivity of isolates that cause diseases in both plants and humans to triazoles. These studies suggested that the selection of fungicides with a similar mode of action as those used in human drug therapy for triazole-resistant isolates could contribute to the development of multi-resistant populations.66,67 The development of cross-resistance to triazoles and the low number of triazoles recommended for human therapy relative to the high number of triazoles used in agriculture may affect triazole efficacy for human therapy.6,10 For instance, the fungus Colletotrichum graminicola that causes anthracnose of corn plants is an emerging pathogen in humans. Resistance to tebuconazole as well as to multiple other azole antifungals has been reported in plant pathogenic populations used in clinical medicine.68,69 Similarly, cross-resistance to triazoles was observed in clinical isolates of Candida albicans and agricultural environmental yeasts.70

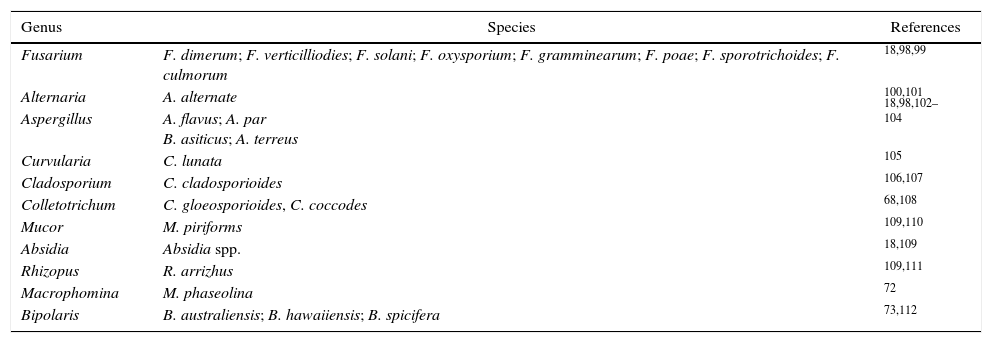

Several other fungi have been found in association with human and animal diseases, including species of several genera such as Bipolaris, Macrophomina, Aspergillus, Fusarium, Alternaria and Mucor18,71–73 (Table 2). The pathogenicity of clinical isolates of the Fusarium solani species complex was confirmed in plants of the Cucurbitacea family, which exhibited similar aggressiveness to isolates originating from diseased plants.17Criptococcus neoformans is also found in different environmental niches, such as plants and animals.74 Fluconazole is the most prevalent clinical antifungal used to treat cryptococcosis.75 However, the continued use of this antifungal is an increasing concern due to the frequency of isolates resistant to triazoles used in human therapeutic use.76 There is a need for attention to azole resistance and optimal therapy in regions with high incidence of cryptococcosis, such as the Asian-Pacific region (5.1–22.6%), Africa/Middle-East (7.0–33.3%), and Europe (4.2–7.1%).77 In addition to fluconazole resistance in these regions, the new point of mutation in the ERG11 gene of C. neoformans afforded resistance to voriconazole (VRC).78 In these cases, the spread of isolates exhibiting resistance to triazoles into the environment and those capable of causing human diseases may affect the efficacy of therapeutic control with fungicides of the same group, especially in the presence of cross-resistance.79

Main genera of fungi reported as the causative agents of diseases in plants and in humans.

| Genus | Species | References |

|---|---|---|

| Fusarium | F. dimerum; F. verticilliodies; F. solani; F. oxysporium; F. gramminearum; F. poae; F. sporotrichoides; F. culmorum | 18,98,99 |

| Alternaria | A. alternate | 100,101 |

| Aspergillus | A. flavus; A. par B. asiticus; A. terreus | 18,98,102–104 |

| Curvularia | C. lunata | 105 |

| Cladosporium | C. cladosporioides | 106,107 |

| Colletotrichum | C. gloeosporioides, C. coccodes | 68,108 |

| Mucor | M. piriforms | 109,110 |

| Absidia | Absidia spp. | 18,109 |

| Rhizopus | R. arrizhus | 109,111 |

| Macrophomina | M. phaseolina | 72 |

| Bipolaris | B. australiensis; B. hawaiiensis; B. spicifera | 73,112 |

The mutagenesis in TR34/L98H in azole-resistant Aspergillus may have originated due to the use of triazole fungicides in agroecosystems.14,28,80 Such mutation was detected in 89% of A. fumigatus-resistant isolates from air samples, flowers, and soils from hospital areas.6 Microsatellite sequencing of clinical and environmental isolates that lead to the TR34/L98H mutation revealed high genetic homology, which suggests a common ancestor.6,13

Future directionsTriazole antifungals largely used in plant protection are also important as antifungal treatments in the human medical field even though they possessing structural differences. However, sensitive populations that co-inhabit environments may be reduced by the selection of isolates resistant to fungicides. Fungi arising from agricultural ecosystems as opportunistic pathogens may carry cross-resistance to triazoles used in the medical field. The restricted number of antifungal agents for clinical use, which contrasts with the large number of agricultural fungicides with similar modes of action, may be a risk factor that limits the success of the therapeutic use of these drugs.

Currently, genome-wide studies, together with novel T-cell-based therapeutic approaches for the prophylaxis and treatment of opportunistic fungal infections, have promising avenues of research in the detection of potentially new antifungal targets.81,82 Thus, different strategies should be the main goals of the pharmaceutical industry.

Given that the search for new antifungal drugs is a lengthy process, the combination of drugs to achieve synergistic effects is currently adopted as an alternative. This approach includes the combination of drugs with distinct mechanisms of action that may enhance efficacy by combining low concentrations of both antifungal agents, thus diminishing the risk of developing resistance.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

The authors are thankful to the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de nível superior – CAPES for financial support. A.M. Fuentefria and H.S. Schrekker are grateful to CNPq for the PQ fellowships.