Introducción: El higroma quístico es una dilatación difusa de los conductos linfáticos. Puede diagnosticarse prenatalmente a través de una ecografía obstétrica. La incidencia aproximada es de 1/6,000 nacidos vivos y de 1/750 abortos espontáneos. Esta lesión puede presentarse a nivel cervical en la parte inferolateral del cuello, donde aparece con grandes cavidades únicas o multiloculares. En general, se producen por la falta de conexión de los vasos linfáticos con los sacos linfáticos yugulares, o de estos con el sistema de drenaje venoso.

Caso clínico: Con el fin de enfatizar sobre la notificación de estas enfermedades y las opciones de tratamiento no quirúrgico, se presenta una paciente con higroma quístico cervical (cara lateral del cuello) con compromiso de la vía aérea y digestiva por la extensión del tumor. Se trató con etanol puro por medio de múltiples infiltraciones guiadas por ultrasonido.

Conclusiones: Dependiendo de las características de la lesión, el tratamiento puede ser quirúrgico, farmacológico o mixto. Cuando la extensión es importante o se relaciona con órganos vitales, la mejor opción de tratamiento es, en primer lugar, reducir el tamaño de la lesión y el compromiso de los órganos contiguos. Esto se hace por medio de escleroterapia. Posteriormente, de ser necesario, se realiza cirugía.

Background: Cystic hygroma is a diffuse dilatation of the lymphatic system, which can be prenatally diagnosed by ultrasound. The incidence is 1/6,000 live births and 1/750 spontaneous abortions. This malformation can occur at the cervical level located in the inferior lateral part of the neck where it appears with large single or multilocular cavities. It is generally caused by a lack of connection with jugular lymphatic channels or with the venous drainage system lymph sacs.

Case report: In order to emphasize these diseases and non-surgical treatment options, we present a patient with a cervical cystic hygroma that compromises the airway and digestive tract due to tumor extension and treatment with pure ethanol with clinical improvement.

Conclusions: Depending on the characteristics of the lesion, treatment options are surgery, pharmacological or mixed. When the extension involves vital organs, the best option is to reduce the size of the lesion and the compromise of the adjacent organ. This is done by sclerotherapy and, if necessary, surgery.

1. Introduction

Fetal cystic hygroma (CH)1 is a benign congenital malformation of the lymphatic system that has its origin in the lack of development of communication between the lymphatic and venous systems. The cyst may be unior multilocular and of a variable size. CH is detected in ∼1/120 of obstetric ultrasounds, with an incidence of 1/6,000 live births.2 This disease is associated with certain chromosomal abnormalities such as monosomy X and trisomy 21, among others. It is also related with some monogenic syndromes, mainly Noonan syndrome and other non-genetic syndromes such as fetal alcohol and fetal aminopterin. Currently the treatment is determined by the site of the injury, whether it is low or high lymph flow and size and organs involved. Therapeutic alternatives include managing the delivery with the EXIT technique (ex utero intrapartumtreatment) to check and ensure open permeable airways at the time of birth using laser, drainage, surgery, aspiration and sclerotherapy.3-5

Currently, we choose to avoid surgical resection as the first treatment choice due to the characteristics of the malformation and involvement of structures like tongue, pharynx, cervical plexus, phrenic nerve, vagus nerve, jugular vein, and carotid artery, among others. The first option is a mixed treatment to decrease the size of the lesion with a less bloody and dangerous approach. To achieve this, we explicitly require the use of sclerosing agents such as corticosteroids, OK-432, bleomycin, sodium tetradecyl sulfate, doxycycline and pure ethanol or even a combination of these agents.6 The function of the sclerosing agent is to increase the permeability of the endothelium, allowing the rapid drainage of the contents, resulting in the contraction of the cystic spaces.7 However, in some cases, their use requires specialized hospital management protocols.5 In other cases its effectiveness has been proven only in case reports.8-10

We present our experience in the treatment of CH using pure, intralesional ethanol as a management option in these patients.

2. Clinical case

We present the case of a 32-year-old mother (G1) with no significant clinical history and with prenatal care beginning in the first month of pregnancy. Cervical mass was documented by fetal ultrasonography at 28 weeks of gestation. At 32 weeks of gestation, the patient went into labor, which could not be delayed; therefore, cesarean delivery was accomplished.

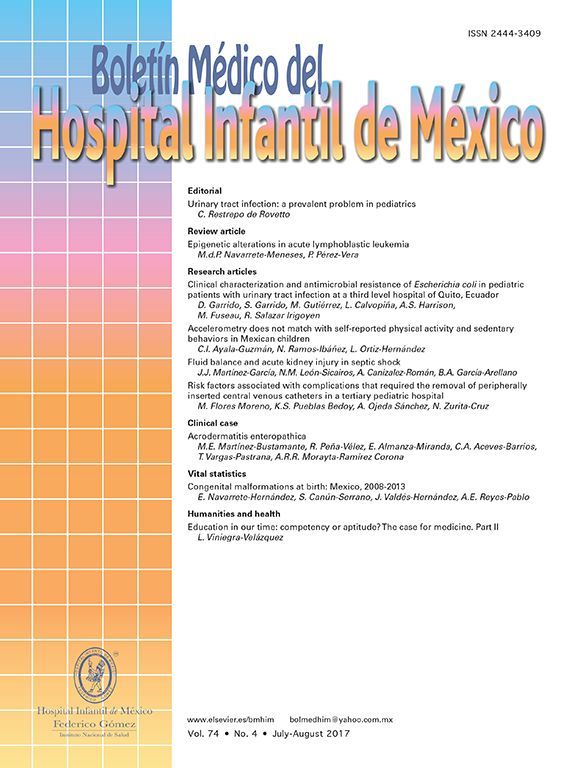

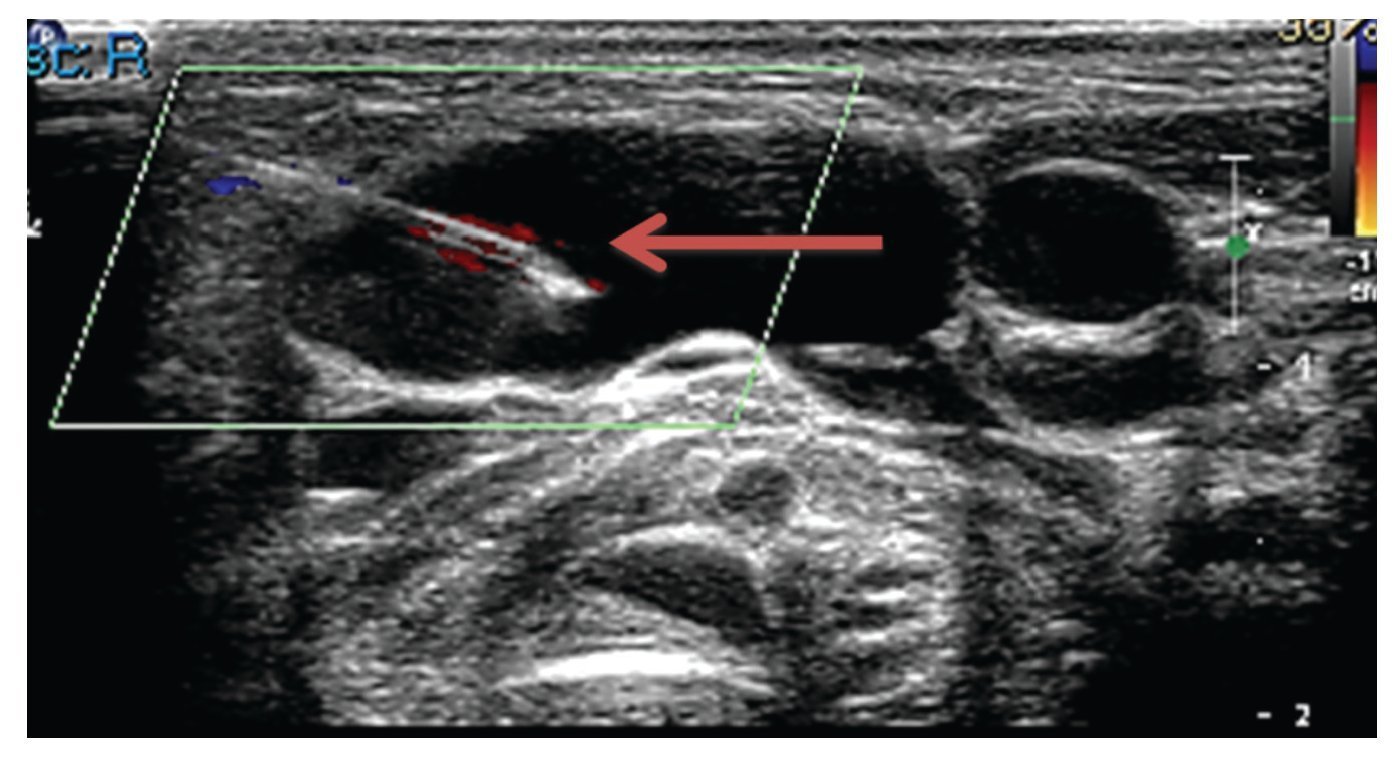

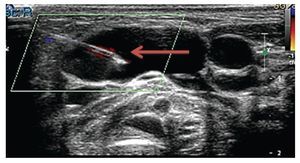

At birth, the infant demonstrated an asymmetrical neck at the expense of apparent right lateral hemihypertrophy, with extension toward the oropharynx, thus obstructing the airway and gastrointestinal tract. Neck and chest x-rays were done and showed the same narrowing of the airway and organ displacement at that level. Mechanical ventilation was initiated. Neck ultrasound revealed a cystic mass with multiple interconnected chambers and varying diameters (Fig. 1).

Figure 1 Ultrasound of the lateral neck where a multi-lobulated cystic lesion is observed. Arrows indicate some of the lobes of the cyst.

In addition to the neck tumor, the presence of another induration was documented at the level of the ventral side of the right arm, ∼2 cm of diameter and with a violet color, which was diagnosed as hemangioma.

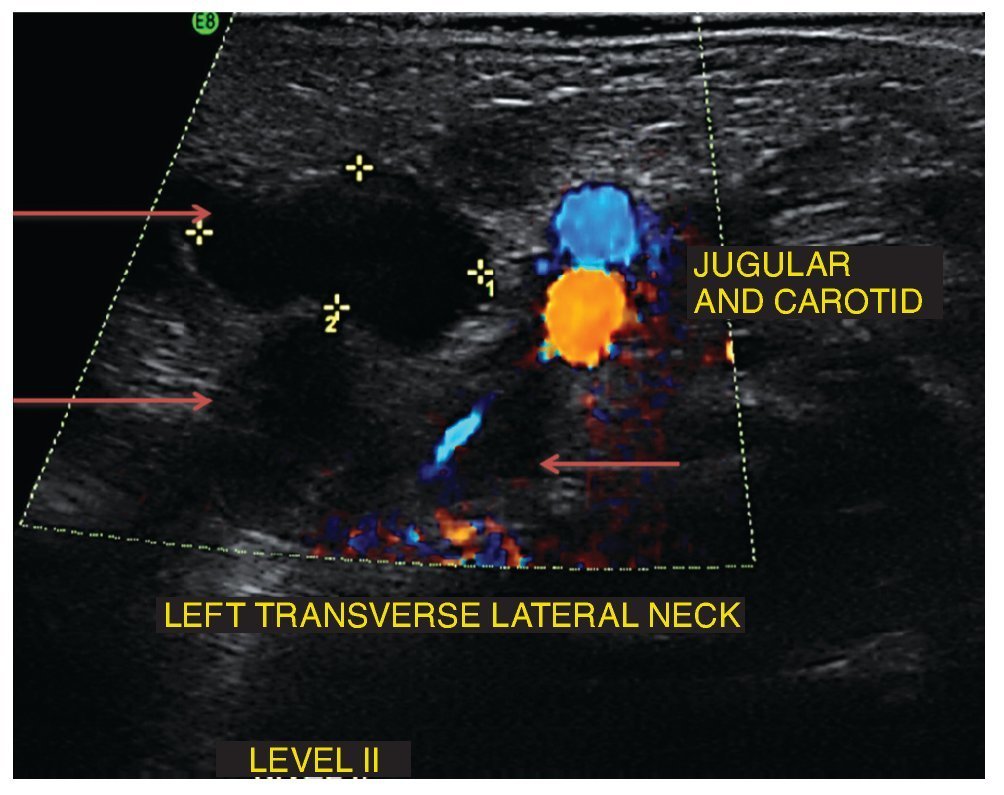

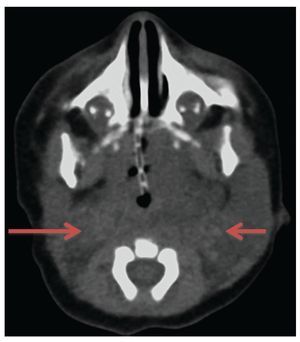

Laboratory studies, blood count, blood chemistry, blood gases and karyotype were normal. Computed axial tomography of the lateral neck showed clear asymmetry in volume with a left predominance at the expense of a hypodense, ill-defined image with apparent liquid attenuation. Vascular structures were shifted medially and later, anterior to the sternocleidomastoid muscle. In this image we observed parapharyngeal fat displacing the air space to the right. Compression and conditioning gauge decreased >50% (Fig. 2).

Figure 2 Computed axial tomography of the head and neck. Increased volume of the neck is observed predominantly on the left that displaces medial and posterior (arrows) vessels, anterior to the sternocleidomastoid muscle, with linear vascular hyperdense images in the interior. Reinforcement is not identified after administration of contrast medium.

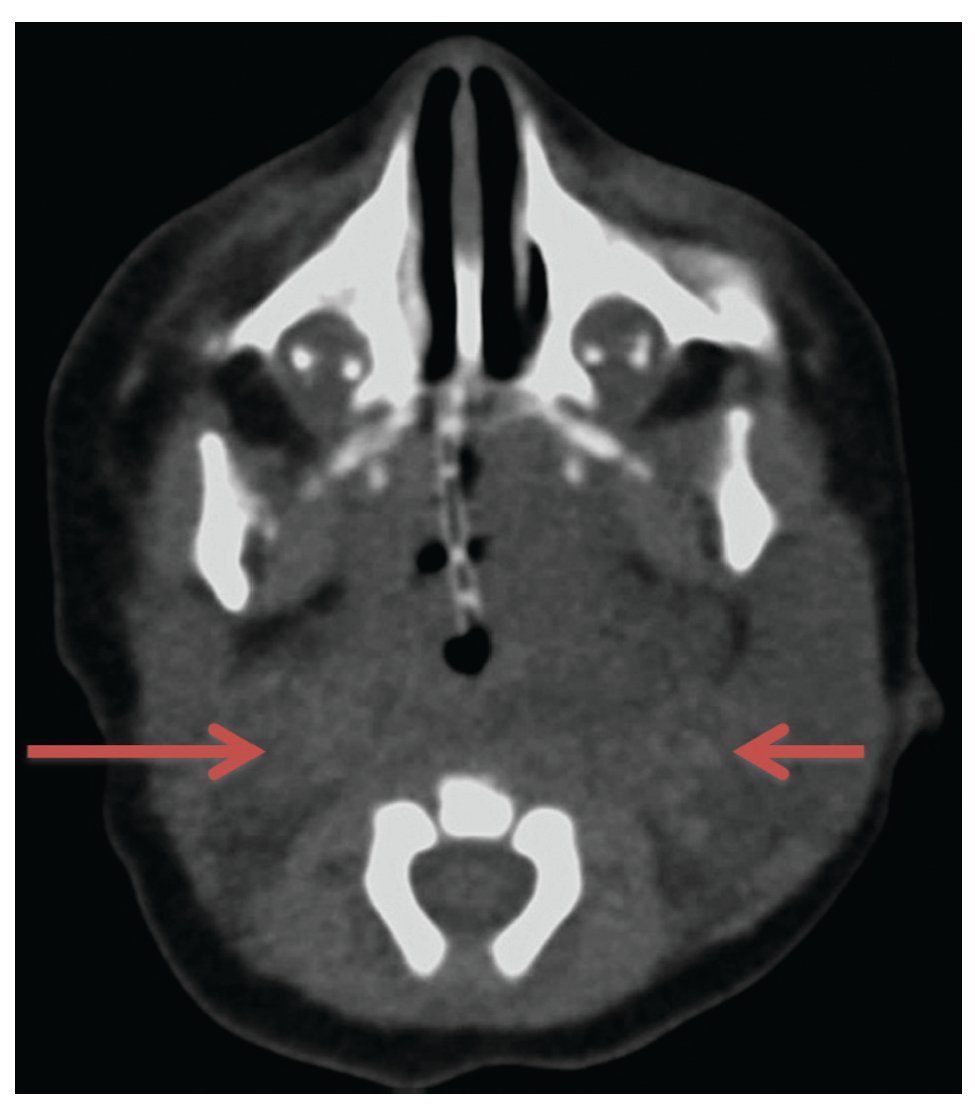

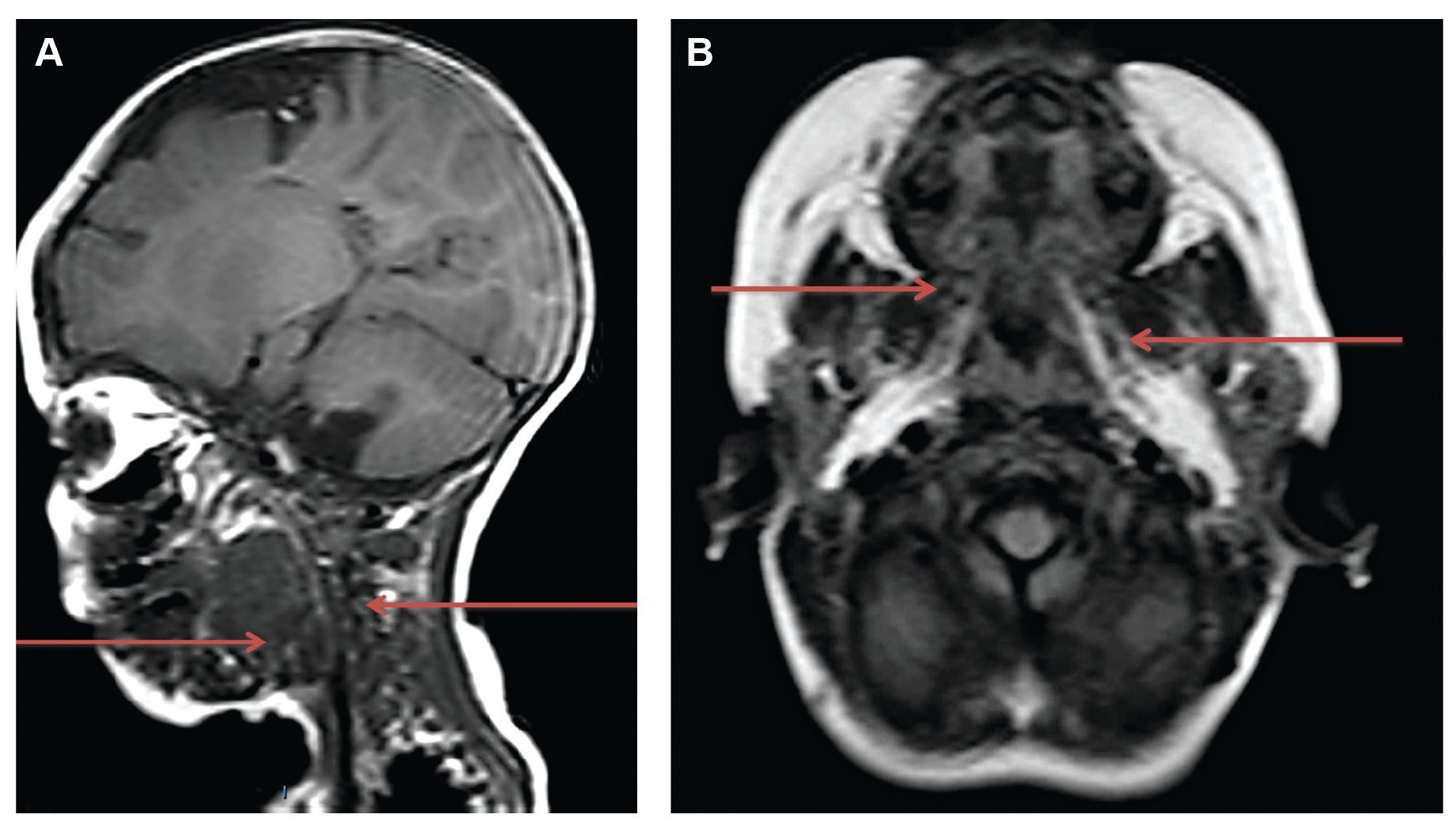

Nuclear magnetic resonance was also conducted. A heterogeneous multilobulated mass was identified. The mass was multicystic and with isointense contents of the muscle on T1, hyperintense on T2, with the main component in the left hemi-neck. This mass occupies the parotid and jugular space with extension to the parapharyngeal and prevertebral areas on the left to the submandibular, sublingual and parapharyngeal space on the right side (Fig. 3), producing a mass effect with contact and displacement of vascular structures on the left posterior side. The mass partially surrounded the internal carotid, producing a mass effect on the airway, which is compressed and displaced to the right of midline.

Figure 3 Nuclear magnetic resonance of the neck. A multicystic, multilobulated and heterogeneous mass is observed (arrow). Mass effect is produced with displacement of vascular structures on the left side. There is compression and displacement of the airway on the right side.

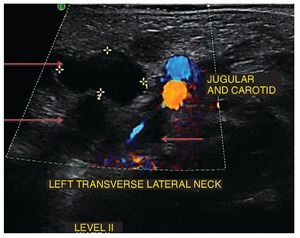

Due to clinical and radiological findings, a pediatric surgery consultation was requested. It was decided that the patient was not a candidate for resection due to the location, extent and involvement of adjacent organs. Because of the decision to not resect the mass, a less invasive option was sought. Based on the experience of the pediatric radiologist in the management of this type of cystic lesion, administration of pure ethanol (100%) was proposed in an infiltration of 0.5-1 ml in eight sessions, one every 2 weeks, using an ultrasound-guided procedure (Fig. 4). After eight sessions, using nuclear magnetic resonance, we documented the decreased volume of the CH and, as a result, increased oropharyngeal space and release of a major gastrointestinal and respiratory area, which allowed autonomous breathing and feeding by mouth.

Figure 4 Insertion of the needle through a lobe of the cyst (arrow).

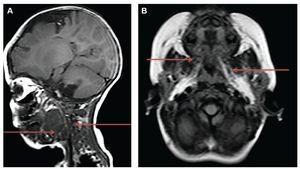

With nuclear magnetic resonance, after infiltration of pure ethanol, a moderate decrease in the volume of the lesion occupying the vascular spaces was observed along with the jaw, parapharyngeal, prevertebral, submandibular and sublingual spaces on the left side. There was also an increase in airway diameter and absence of movement that supports the efficacy and reports minimal adverse events.11 However, its use is not compared with other treatments. Other relevant publications are those of Cuervo et al.8 and Lobo et al.,12 denoting its effectiveness in uniand macrocystic hygromas. Several treatment sessions are often necessary and supplement with surgery is sometimes necessary to obtain a satisfactory result.

With regard to ethanol, Burrows et al.13 reported its use at rates of 95-98% as an aggressive sclerosing therapy because of the sudden precipitated proteins in endothelial injury. This will exceed the dose of 1 ml/kg or 60 ml and with potential side reactions such as tissue necrosis, (Fig. 5). Currently, the patient is under clinical management due to additional diseases caused by prematurity and is awaiting definitive surgical treatment.

Figure 5 Nuclear magnetic resonance of the neck and facial mass (A) and skull (B). A moderate decrease is observed in the volume of the lesion within the vascular spaces and jaw and parapharyngeal, prevertebral, submandibular and sublingual locations on the left side when compared with the previous study (arrows), mainly at the expense of cystic portions.

3. Discussion

Treatment of CH depends directly on the size, location, organs involved and patient condition. Currently, there is a published study of case reports that supports treatment with various sclerosing agents, for example, the use of OK-432. Vincent et al. published a review of the literature pulmonary embolism or central nervous system depression. In 2010, Impellizzeri et al. reported results of complete disappearance of the lesion in 7/8 of the patients (87.5%). One patient with satisfactory results required a second injection of ethanol, resolving 100% of the lesion without allergic reactions or complications. With that, the authors concluded that CAT-guided ethanol sclerotherapy is a good alternative to surgical therapy. In addition, the procedure is minimally invasive, safe, inexpensive and reliable.14

As noted, recommendations have been made on the use of pure ethanol for these types of conditions. In order to emphasize reporting of these diseases and development of clinically relevant evidence, in this paper we present a case of pure ethanol treatment for these lesions with no immediate complications except minimal local pain and with the benefit of liberation in a clinically significant percentage of air and food passages where the patient was able to be autonomous. However, we must emphasize that the evidence is not yet sufficient to recommend the use of alcohol in all patients. Therefore, development of studies that support the effectiveness attributed to such therapy is indispensable.

CH, although described as a benign disease, may have complications that compromise the patient’s life. Therefore, it remains relevant to individually assess whether surgery is the most viable option or the use of long-term treatment with sclerotherapy.15 Early diagnosis and management of individuals with CH can reduce the risk of complications in these patients, but treatment is still dependent on the experience of the healthcare professional,16,17 whether empirical, reported in case studies or in isolation in case reports.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest of any nature.

Received 2 Apr 2014;

accepted 29 Jul 2014

* Corresponding author.

E-mail: luciamendezs@gmail.com (L. Méndez-Sánchez).