Una prueba de tamiz es una herramienta cuya función es identificar individuos presuntamente enfermos en una población aparentemente sana al establecer el riesgo o sospecha de un problema de desarrollo. Debe tenerse precaución y ser muy cuidadoso al utilizar un instrumento de este tipo, por el riesgo de efectuar mediciones que no coincidan con la realidad y retrasar una intervención a quien lo requiere.

Antes de incorporar una prueba de este tipo como parte de la práctica clínica rutinaria, es necesario certificar que posee ciertas características que hacen meritoria su utilización. A este proceso de certificación se le denomina validación. El objetivo de este artículo fue describir los diferentes pasos que se llevaron a cabo desde la identificación de una necesidad de detección hasta la generación de una prueba de tamiz validada y confiable, utilizando como ejemplo el proceso del desarrollo de la versión modificada de la prueba Evaluación del Desarrollo Infantil (EDI) en México.

A screening test is an instrument whose primary function is to identify individuals with a probable disease among an apparently healthy population, establishing risk or suspicion of a disease. Caution must be taken when using a screening tool in order to avoid unrealistic measurements, delaying an intervention for those who may benefit from it.

Before introducing a screening test into clinical practice, it is necessary to certify the presence of some characteristics making its worth useful. This “certification” process is called validation. The main objective of this paper is to describe the different steps that must be taken, from the identification of a need for early detection through the generation of a validated and reliable screening tool using, as an example, the process for the modified version of the Child Development Evaluation Test (CDE or Prueba EDI) in Mexico.

1. Introduction

The construction of a solid foundation for healthy development during the first years of life is a fundamental requirement for individual well-being and economic productivity, successful communities and harmonious civil societies.1 The architecture of the developing brain is constructed through a process that starts before birth, continues into adulthood and is established as a base, either strong or fragile, for health, learning and subsequent behavior.2

During the first 5 years of life there is a succession of sensitive periods, each related to the formation of circuits associated with specific abilities. Thus, brain functions have a critical period of maximum potential of development in concert with age. The level of development reached depends on the interaction of genes and early experiences.3 Based on the above, the concept of early childhood development (ECD) emerged, which covers from pregnancy and up to 6 years of age, and is a process of change in which the child learns to master always more complex levels of movement, thinking, feelings and relations with others. It occurs when the child interacts with people, objects, and other stimuli in the biophysical and social environment and learns from them.4

While the maturing brain specializes in taking on increasingly complex roles, it also becomes less able to reorganize and adapt to new challenges. Once the circuit has installed itself, it will stabilize with age, making its later alteration difficult. Although the windows of opportunity may remain open for many years, modifying behavior or constructing new skills on top of the brain circuits that were not properly installed when they were formed for the first time requires too much work. Additionally, greater amounts of metabolic energy are required to compensate for function of circuits that do not work as expected.5 Doing things correctly the first time rather than waiting and trying to correct them later is less expensive both for individuals as well as for society in general.2 For this reason the correct formation of these circuits should be monitored.

Evaluation of childhood development is a process geared towards knowing and quantifying the level of maturity reached by a child compared with his/her age group,6 which allows to identify changes and establish an individualized profile about the strengths and weaknesses of the different domains evaluated. Early detection of developmental problems is of utmost importance for the wellbeing of children and their families because it allows achieving a timely diagnosis and treatment7 and implement actions within the windows of opportunity to avoid consolidation of inadequate circuits and allow their reorganization in an optimal fashion. These actions allow for children to develop increasingly complex skills commensurate with their age and thus to achieve their full potential.

The clinical judgment of medical personnel is not sufficient for carrying out this evaluation and identifying patients with developmental delay. Hence, the importance of using standardized tools to detect these patients.8 A screening test is a tool that has as its function to identify presumably ill individuals in an apparently healthy population by establishing a risk of suspicion of a developmental problem. One must act cautiously when using an instrument because of the risk of assessing measurements that do not coincide with reality and delay an intervention in those who do require it.

Before a test of this type is incorporated as part of routine clinical practice it is necessary to certify that it has certain characteristics that make its use worthwhile. This certification process is called test validation.9 There are various processes that have been considered as validation without actually being so. The most common is to do only translations, to only carry out tests of concordance or correlation with the results of measurements with other tools or carry out only tests of concordance between different evaluators.10

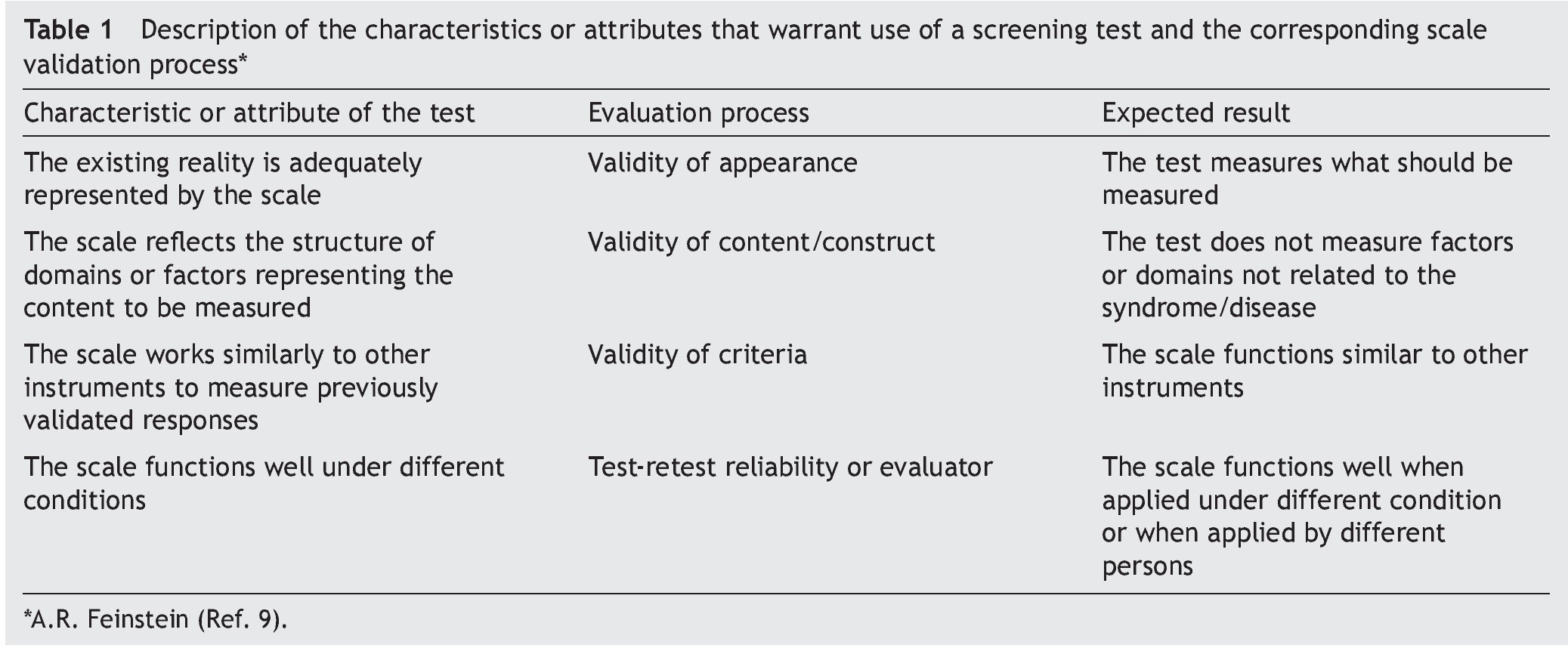

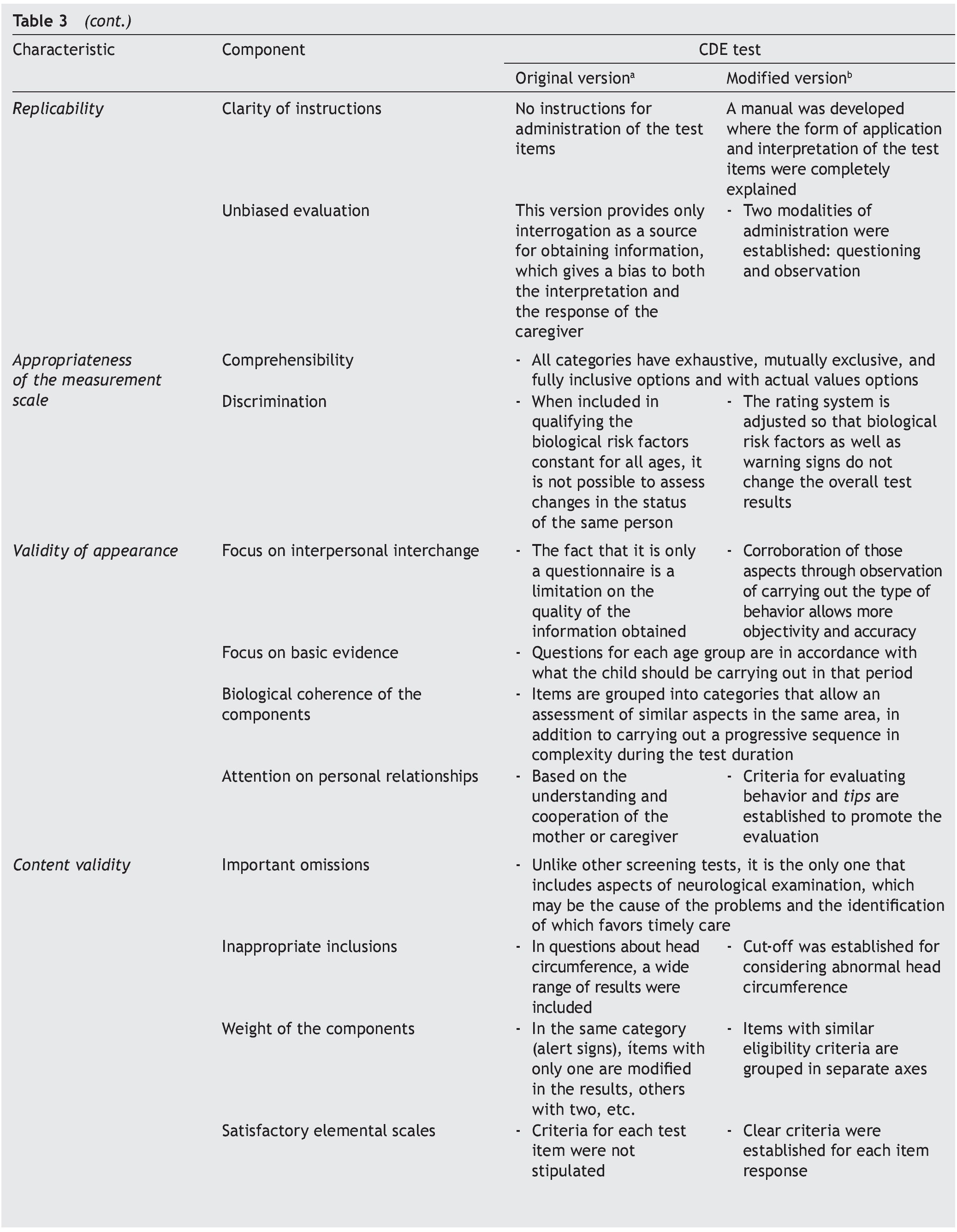

The objective of this article was to describe the steps that have been carried out for the validation of screening tests (Table 1), using as an example the process of development of the modified version, validation and evaluation in the field of the CDE test. These steps should answer a series of questions.

• Are there tests that reliably quantify what one desires to measure?

The scale to be used should be the best available. For this, it is important to first analyze if there is an instrument that meets the objective desired.10 In the case of screening tests for childhood development in Mexico, given the interest of having a valid tool for timely detection, a systematic review was done based on the information available in databases and search engines of scientific publications.11 There was no information found in the scientific literature on any screening test validated in Mexico. On the other hand, the tests available in America had deficiencies or different characteristics, which did not make them the most adequate for their implementation in Mexico. As part of the NOM-031-SSA1-1999, for child health care,12 item 9.6.1 specifies that evaluation of the psychomotor development of the child should be done each time the child presents for consultation for monitoring nutrition and growth status, using as a reference of normality of behaviors specified in Appendix F of the same document. There was no available information found on the values of the tests contained in this Appendix (sensitivity/specificity) nor of apparent process of validation or of criteria. In addition, as result of the test, it is only reported if the child was identified as having signs of alarm. Due to these data it was concluded that “there is no agreement on how to evaluate the physical, cognitive, social and emotional development of children in Mexico. The data used to measure them are the enrollment of boys and girls in preschool education or their registration in child care programs”.4

• If there are plans to design a new tool, what clinical functions should be met and how would it be structured?

The tool that would be required in Mexico should meet the following clinical functions:

a) Qualitative characterization of the level of development of the children. Identification of changes over time that will enable interventions appropriate to the needs of children

b) Serve as a basis for a management guideline.

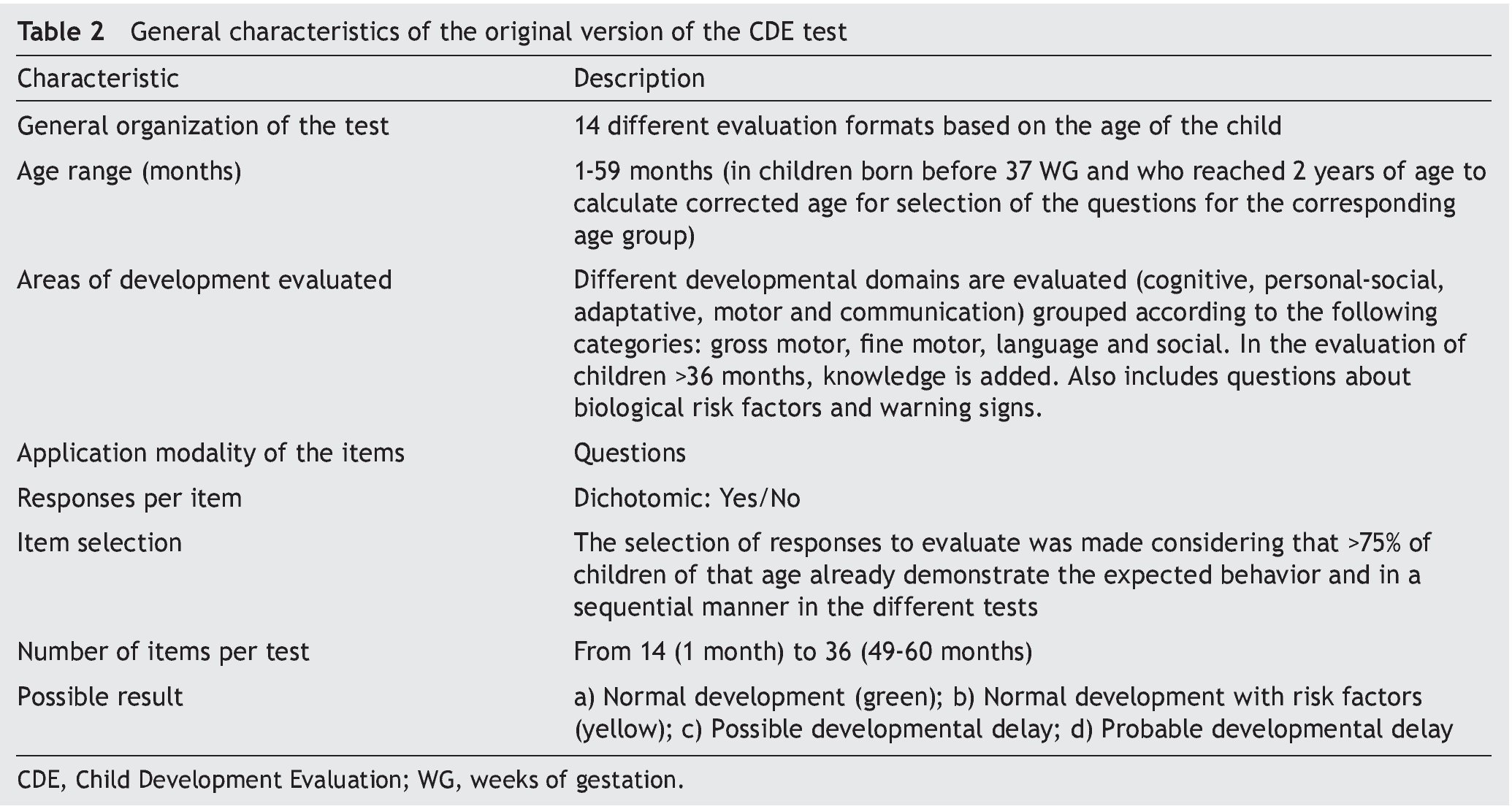

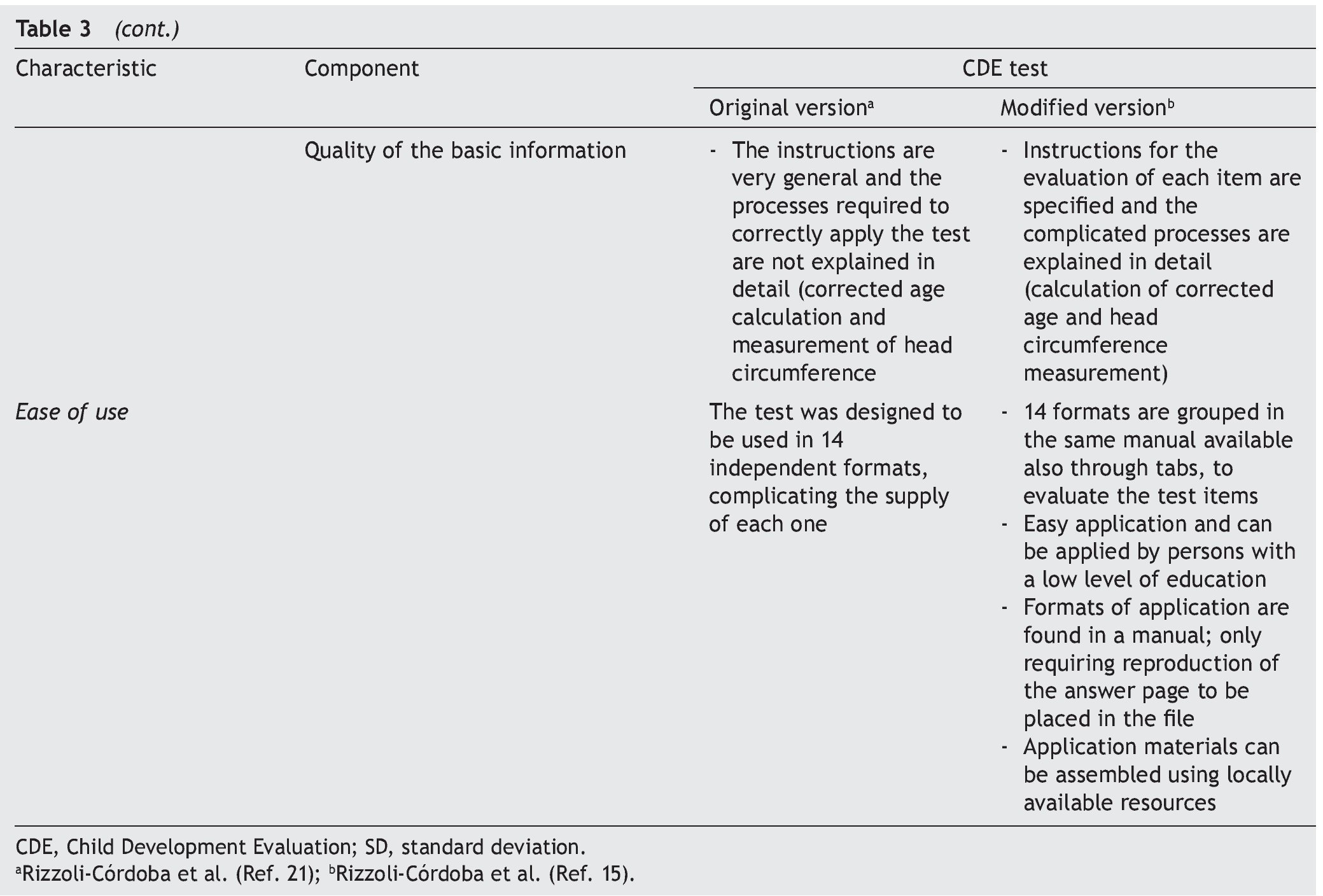

In the absence of evidence that meets these functions, the members of the General Directorate of the Opportunities Program (today PROSPERA) in 2010 asked Dr. Lourdes Schnaas of the National Institute of Perinatology to design a screening test for child development evaluation (CDE) in its original version.13 This test would function as a tool for the timely detection of developmental problems in boys and girls from 1 month of life and up to one day before their fifth birthday, using a semaphore system of scoring: green (normal development), yellow (lag) or red (risk of delay) (Table 2).14

2. Validation process of a screening test

Once an instrument has been designed or identified that could be useful for meeting the objective of identifying in a timely manner the disease or phenomenon of interest, the evaluation of the validity seeks to answer the following questions:

• Does the scale appear to measure what it should measure? Does it reflect the structures of the domains of the phenomenon to be evaluated?

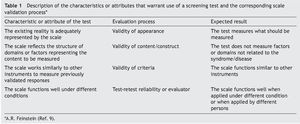

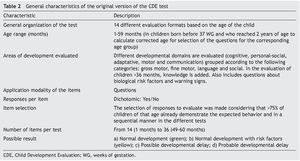

It is essential to answer the first question to establish the acceptability of the test in the application scenario, thereby establishing the validity of appearance.9 This validity depends on the analysis of the appearance of the test and their items as they seek to evaluate the phenomenon of interest (focus on interpersonal exchange, basic evidence, biological coherence of the components, attention to personal collaborations). The answer to the second question attempts to analyze the different components of the test to establish whether the instrument reflects the concept that it is intended to measure (important omissions, inappropriate inclusions, weight of components, satisfactory basic scales and the quality of the basic information) and with it establish content validity.

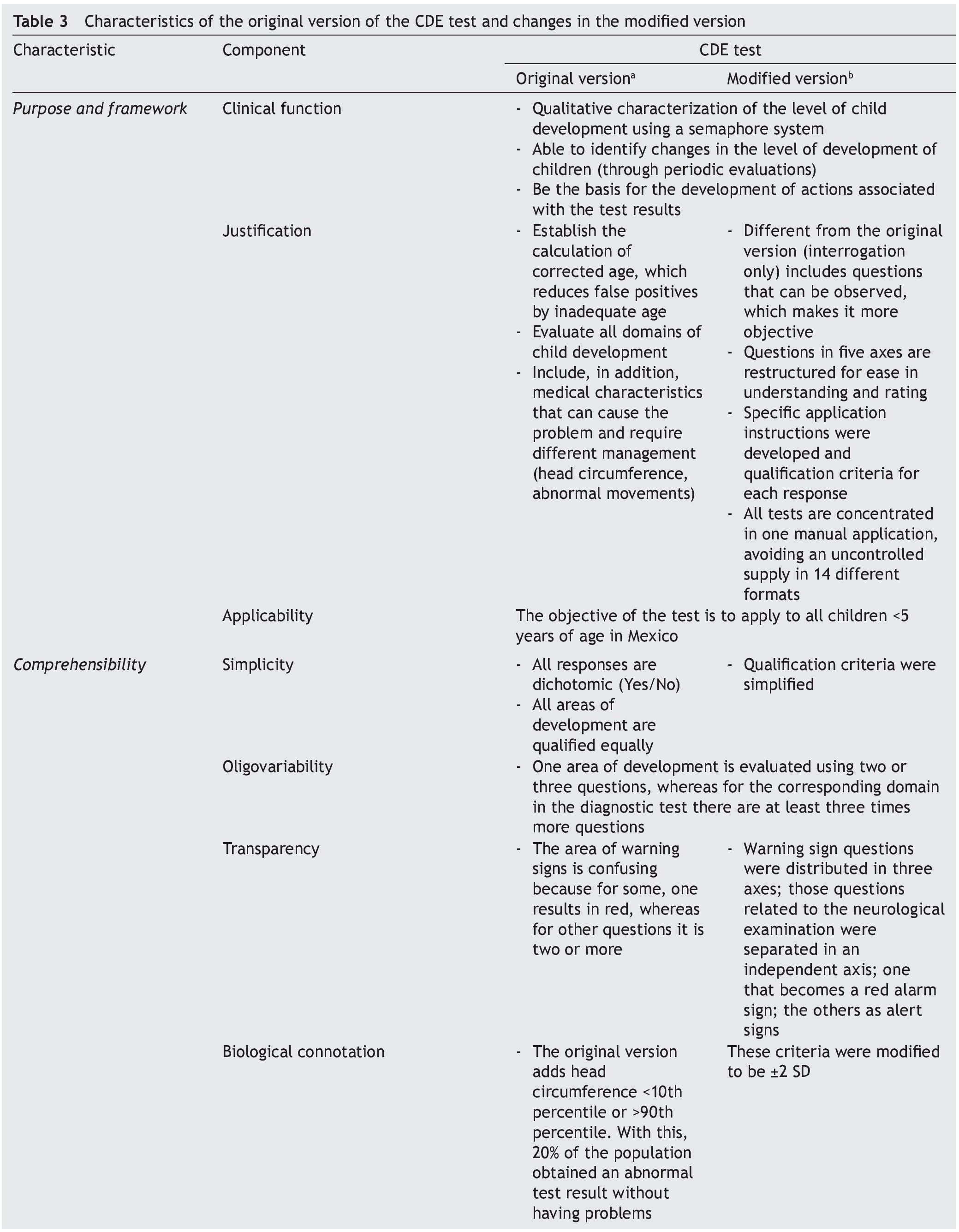

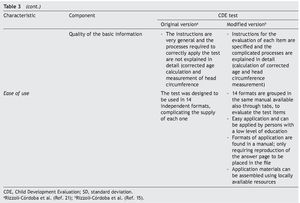

To answer these questions, a thorough analysis of the original version of the CDE test was conducted. Areas of opportunity were detected from which a modified version was developed.15 Precise scoring criteria and instructions were developed for each of the questions, the questions were reorganized in axes with common characteristics, the overall scoring criteria were modified for greater congruence and the modality observed was added in the items that were considered relevant. These modifications were carried out to adequately meet the requirements of appearance and content validity (Table 3).

Once the appearance and content validity were achieved, a validation by consensus was sought. To this end, a panel of experts was organized who analyzed each of the items of the CDE test, comparing the two versions of the test using a modified Delphi panel methodology. This panel arrived at the conclusion that the modified version of the CDE test was the most appropriate screening instrument for the assessment of children <5 years of age in the context of the country.16 In addition, it was established that the Battelle Developmental Inventory 2nd ed. in Spanish (BDI-2) was the most adequate instrument for diagnostic corroboration.17

• Does the test function similar to other validated instruments?

To answer this question, it is necessary that the tests be subjected to a concurrent criterion process of validation. This process seeks to determine the extent to which such test results coincide with diagnostic evaluations considered to be the gold standard or with those commonly used and considered as reference.18 For this, an appropriately designed study is required,19 considering the quality of the evaluation and the risk of bias.20

A validation study allows establishing the ability of the test for the following characteristics: a) identify as abnormal those persons with the disease (sensitivity); b) identify as normal those persons without the disease (specificity); c) determine the percentage of the total persons who obtain a normal result in the screening test in which the disease is corroborated (positive predictive value); and d) determine the percentage of the total persons with normal results in the test who really do not have disease (negative predictive value). In the case of screening tests, it is recommended that they have values of sensitivity and specificity >70%.18

To determine the properties of the CDE test in its two versions (original and modified), validation studies of concurrent criteria21 were carried out against two instruments of evaluation of development considered as the reference standard: BDI-217 and Bayley-III.22 As a secondary objective of this study the analysis of components evaluated was done (domains of development)23 and for the differences by abnormal results (yellow vs. red).24 According to the design of the study and with the results obtained and by a comparative analysis of the screening tests for problems in development designed and validated in Mexico, it was identified that the validation study of the CDE test had the least risk of bias in the data published.25

Once the validity of the test is established, there are two additional questions to consider in order to contextualize the reliability of the results of the application in the field.

• In its field application, are there results similar to what has been described in the validation criteria?

Once the properties of the test have been identified in the validation study, it should be known if they are maintained in their application in the field. To determine this a study was carried out that included children from 16-59 months of age identified with risk of delay in the CDE test and in whom it was sought to establish diagnostic confirmation of delay though the application of the BDI-2. In this study it was found that 93.2% of the children identified with risk of delay according to the CDE test had diagnosis of delay in at least one domain evaluated by the diagnostic test.26

This result was similar to that described in the study of validation criteria (93.8%),21 corroborating the reliability of the results when applying the test in the field.

• Does the scale function well when it is applied at different times or when it is applied by different persons?

If a patient is evaluated at the same time by two different evaluators, the results of the evaluation should be similar; this is what is measured by the inter-evaluator reliability. Concordance in the result of the test when the same patient is evaluated on different occasions in a short time frame is referred to as test-retest reliability. In a study with the objective of evaluating a model of supervision that would allow identifying the quality of the application of the CDE test at the populational level, an inter-evaluator concordance of 86.1% was found through the simultaneous application of the test as a shadow study, and a concordance in the re-application of the test between the supervisor and the person administering the test of 88.1%. These differences in the results were associated with the incorrect administration of some of the items by specific personnel, reinforcing the need of accompanying and verification of the correct application in the field in order to obtain reliable results.27

For the timely detection of problems in the CDE, the following should be proposed as a first line: a) screening tests that appear to measure what they should measure (validity of appearance); b) include all developmental domains to be evaluated (construct validity) that when compared with diagnostic evaluations considered to be the gold standard have values of specificity (total percentage of persons with normal development by the gold standard which the screening test identifies as normal) >70% (validity of criteria);18 c) have similar results when given at different times or by different persons (test-retest or evaluator reliability) given that childhood development is a process of change; d) detect these differences with the passage of time (sensitivity to change); and e) be quick and easy to administer so that they can be used by nonspecialized personnel in primary care units (usefulness).28

The evidence available on the CDE test confirms the compliance of each of the above-mentioned points, for which it is currently considered to be most appropriate test for timely detection of developmental problems in Mexico16 and is the test recommended by the National Center of Childhood and Adolescence for evaluation of childhood development in primary care units in the country.29 The analysis of the information obtained through its field application will allow for identification of areas of opportunities and to confirm if the results of the different validation steps are consistent when applied as part of a public policy.

Funding

No external funding was used for the study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Onofre Muñoz Hernández (Doctoral advisor); Dr. Juan Garduño Espinosa, Dr. Camilo de la Fuente Sandoval, Dr. Ricardo Pérez Cuevas (Doctoral Advisory Committee); Dra. Lucina Isabel Reyes Lagunes, Dra. Hortensia Reyes Morales, Dra. Guadalupe Silvia García de la Torre, Dr. Miguel Ángel Villasís Keever (jury for evaluation); Dra. Rosa Elba Leyva Huerta, Mtra. María de los Ángeles Torres Prieto, Lic. Magnolia Silva Méndez (Coordinación de Posgrado de la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México); Dr. Gabriel O’Shea Cuevas, Dr. Daniel Aceves Villagrán, Lic. Joaquín Carrasco Mendoza, Mtra. Fátima Adriana Antillón Ocampo (Comisión Nacional de Protección Social en Salud); Dr. Mariano Ramírez Degollado, Amapola Adell Grass, Dr. Daniel Carrasco Daza (in memoriam).

Received 5 November 2015;

accepted 7 November 2015

* Corresponding author.

E-mail:antoniorizzoli@gmail.com (A. Rizzoli-Córdoba).