1. Introduction

Child development is a health topic that has experienced a great boom in recent years, originating from the recognition of the rights of children <5 years of age. Evidence demonstrates the impact of this stage on the rest of life and there is a paradigm shift of not viewing the budget earmarked for the first years of life as an expense but rather as an investment. The objective of this paper is to describe the actions in terms of public health carried out in Mexico in recent years by the Social Protection System in Health, with the purpose of allowing all children <5 years of age, especially those in vulnerable situations, to reach their maximum developmental potential before their admission to elementary education through early detection and timely care of developmental problems.

2. Rights and Social Protection in health focus in childhood

The Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) establishes that all persons <18 years of age have the right to survival, food and nutrition, health and housing, living within a family whose main concern is their greater well-being, and a proper orientation in line with the evolution of their abilities. The Committee on the Rights of the Child issued in 2005 the General Comment number 7 with some recommendations for the implementation of child rights in early childhood. This establishes that young children are beneficiaries of all rights framed in the CRC and, in accordance with their evolving abilities, must be progressively exercised.2 Mexico was one of the first countries to sign these documents.

In December 2014, the Federal Executive issued the General Law of Children and Adolescents Rights,3 which aims to recognize children as holders of rights in accordance with the principles of universality, indivisibility, interdependence and progression. In the exercise of their rights, children <5 years of age have special needs of physical care, emotional care and careful guidance, as well as time and space to play, explore and be exposed to social learning.4

The Federal Government, through the National Commission on Social Protection in Health (CNPSS), seeks to provide children who do not have social security the access to a scheme of financial protection that protects the health and wealth of families through different strategies:

• The health component of PROSPERA Program of Social Inclusion, which carries out health promotion actions for disease prevention and promotes access to quality health services, mainly for children and adolescents from homes with a per capita income below the minimum welfare line (MWL) whose socioeconomic conditions and income may prevent the members from achieving an appropriate level of nutrition, health and education.5

• XXI Century Medical Insurance (SMSXXI) that finances complete and global medical care of those children who do not have any type of social security.6

Through the actions by the CNPSS, the rights of children <5 years are exercised, in particular among the most vulnerable populations (those in poverty).

3. Early childhood development and risk factors

Early childhood development (ECD), which ranges from pregnancy up to 6 years of age, is “A process of change in which a child comes to master more and more complex levels of physical activity, thinking, feeling, communicating, and interactions with people and objects.3”

It is produced when the child interacts with persons, objects and other stimuli in the biophysical and social environment and learns from them. For children to progress in this manner, it is important that they have life, good health and nutrition as a basis for development as well as meeting the needs of attachment, social interaction, communication, emotional safety, consistency and access to opportunities for exploration and discovery.7

For childhood development, the first 5 years of life are crucial because 90% of the brain is developed during these years. There are critical periods of maturation of sensory circuits, language, and the basis for cognitive functions. During this period, the majority of connections are established and life-long circuits are consolidated.8 Brain development can be altered by the quality of the surrounding environment of children, and there are risk factors identified with this, such as poverty, malnutrition, health problems and environments with little stimulation.9,10 These factors are associated with cognitive, motor and emotional development delays. Prevalence of these risk factors in Mexico is described in Table 1.11-13

Despite the vulnerability of the brain exposed to these risk factors, health problems or an adverse environment, there may be a significant recovery with some interventions, taking into account that the earliest the interventions are provided the greater benefit they will yield.10 In addition, timely detection of developmental problems allows access to early diagnosis and treatment that will promote a positive outcome, which is of utmost importance for the well-being of children and their families.14

4. Legal and regulatory framework for early childhood development in Mexico

The National Development Plan 2013-2018 establishes, as lines of action within the national goal number II “Inclusive Mexico”: “To promote actions of early childhood development (objective 2.1, 2, strategy 1.2)” and “To promote the complete development of children, particularly in terms of health, food and education, through the implementation of coordinated actions among the three orders of government and civil society (objective 2.2, strategy 2.2.2)”.15 The health sector program 2013-2018 includes “To foster the development of abilities to offer children healthy child-rearing practices and early stimulation (strategy 4.1, paragraph 4.1.7)” and “Reinforce community action on child development and initial education (strategy 4.1, paragraph 4.1.9)”.16

Health care of children <5 years of age in Mexico is described in the NOM-031-SSA2-1999 for the healthcare of the child. In paragraph 9.16 it is stipulated that growth and development surveillance of children are basic actions for health care and paragraph 12.2 stipulates the promotion of community participation in the actions that support growth and development. Appendix F includes a technical guideline with the description of behaviors to be evaluated in order to assess child development.17

5. CDE test

With the aim of having a tool for the early detection of developmental problems in children <5 years of age in poverty, the design and validation of the screening tool: Child Development Evaluation Test (CDE test or Prueba Evaluación del Desarrolo Infantil or EDI in Spanish) was made, financed by the CNPSS through PROSPERA.18 During the international panel of experts “Validation of Instruments Diagnostic of Childhood Developmental Problems in Mexico”,19 it was concluded that the CDE20 test was the most adequate screening instrument in the context of the Mexican population, and Battelle Developmental Inventory (BDI-2) was the most suitable instrument for diagnosis of developmental delay.21

Starting in 2014, the CDE test replaced the previous technical guideline and, together with the BDI-2 and early stimulation by competencies, is part of the new technical guidelines for early child development that outline the care of children <5 years of age in this matter throughout the country.4

6. Child development within the PROSPERA program

In order to align and strengthen actions that contribute to monitoring, care and promotion of the optimal development of children living in conditions of marginalization, the child development strategy was developed in 2012, taking as core actions the mass implementation of CDE testing along with an activities proposal derived from its results.

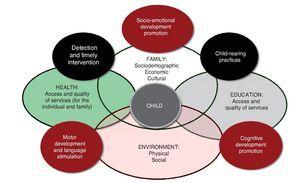

With the goal of strengthening and expanding this strategy, in 2013, the model of Promotion and Care of Childhood Development (PRomoción y Atención al Desarrollo Infantil-PRADI) was developed with technical counseling from the Hospital Infantil de México Federico Gómez (HIMFG). This model focuses on improving the development of children <5 years of age in the motor, cognitive and family socio-emotional areas by generating specific actions that favor child development in the different social spheres in which they interact. It is based on improvement of rearing practices, detection and timely care, organized into two components: a) early detection and timely care and b) education at the community level (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Activities of early child development in the different areas that include the Model of Promotion and Care of Child Development [Modelo de Promoción y Atención del Desarrollo Infantil (PRADI)] developed for the PROSPERA Program of Social Inclusion.

6.1. Component of early detection and timely care

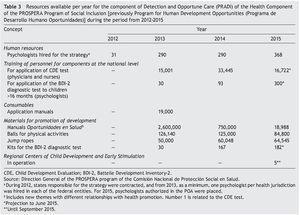

Early detection and timely care is the most developed component and the one with more results because it was the first to be put into practice by the application of the CDE test nationally. Its objective is early identification and timely care of children identified with developmental problems through the use of a single screening tool for developmental problems (CDE), to provide timely care with early stimulation actions to children living in poverty with normal development, and to strengthen referral networks and follow-up of children with developmental delays at the first level of care, as well as to provide a diagnosis for children >16 months of age with developmental disorders. Table 2 describes the differences by year in the investment in health amounts. Table 3 shows the differences in resources for childhood development.

Thirty one psychologists with clinical experience were hired for the implementation, operation and supervision of this component in 2012; and for 2013 a panel of 290 psychologists were available (at least one responsible statewide and a psychologist for each health jurisdiction); for 2015 there was a 26.9% increase, with a total of 368 psychologists, of whom 90% had been trained in the application of the BDI-2 diagnostic test and are in the process of being certified for its application.

For the evaluation of child development, a manual of application for the CDE20 test was designed and 25,000 copies were printed and distributed in the 31 states where the PROSPERA program exists, providing at least one manual to 100% of the country’s health units.

A training model and a manual were developed for the facilitators.22 In October 2012, personnel of each of the 32 federal entities were trained in the application of the test, with the goal that each of them would replicate this training in their federal entity. From 2013, training has been conducted for the operative personnel of the health units (physicians and nurses). During that year, there were 15,000 persons trained. During 2014, there were 33,445 persons trained and 16,700 in the first semester of 2015. With this, 80% of the health units have at least one trained person in the application of the CDE test. Given that there is a high rate of personnel turnover, training should be an ongoing process.

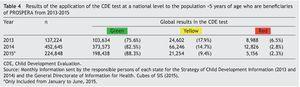

As a result of the training, the number of children evaluated went from zero in 2012 to 137,224 in 2013, 452,645 in 2014 and 224,848 children evaluated in the first semester of 2015 (Table 4). During 2013, a model of supervision for the correct application of the test was developed, which is of the utmost importance in order to have reliable information and to accurately identify those children at risk of delay.

To bolster the development of children in a family environment, health promotion materials have been created and child development was included as a health topic within the self-care workshops.

To facilitate the assessment of children identified at risk of delay, a consultation manual19 and a manual of neurological examination23 were developed, and the pediatricians of the health services of 20 federal entities (64.5%) have been trained in the diagnostic evaluation. Financial resources for care at the second level comes from the SMSXXI. One of the challenges identified is the referral and counter-referral of the children who so require. To facilitate these processes, meetings have been held to create or enhance care and referrals networks in 29 entities (93.5%). For the diagnostic evaluation of children >16 months identified with risk of delay, there was an increase in BDI-2 kits available, from 30 in 2013 to 182 kits in the first semester of 2015. The goal is to have at least one diagnostic test kit per health jurisdiction.

In order to provide comprehensive, decisive and prompt care of children identified at risk of delay, in 2015 8.3 million pesos were provided to each federal entity for the creation of a Regional Center for Child Development and Early Stimulation (CReDI). The purpose of the CReDI is to establish themselves as units of care with functions relative to the performance of diagnoses, management plans, referral, research and training as well as the state coordination of the Childhood Development Strategy. These units are authorized to carry out the components of the strategy, perform early detection and timely care of developmental problems and to conduct early childhood learning workshops. For September 2015, there were five centers in operation in the following states: Michoacán, Nuevo Leon, Yucatan, Guerrero and Sinaloa.

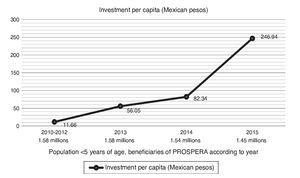

During 2010-2012, prior to the implementation of the strategy, $13,865,000.00 Mexican pesos (MN) were invested in child development research (design, validation, development and training). In the first year of implementation of the model, $87,166,996.00 MN were invested, which corresponded to a per capita investment of $55.00 MN, which increased to 408% by 2015, largely due to the investment of $254,200,000.00 MN allocated to the creation of the CReDI (Figure 2). With this, it is expected that quality care will be provided to children. The impact of these measures will have to be necessarily evaluated in the future. Figure 3 shows implementation progress according to state.

Figure 2 Annual investment per capita in early childhood development (2012-2015) for the population <5 years of age who are beneficiaries of the PROSPERA Program of Social Inclusion.

Figure 3 Level of advancement in the activities of the Component of Detection and Early Care in the federal entities, carried out by the National Commission for Social Protection in Health [Comisión Nacional de Protección Social en Salud (CNPSS)] in conjunction with the National Center for Child and Adolescent Health [Centro Nacional para la Salud de la Infancia y la Adolescencia (CeNSIA)], Hospital Infantil de México Federico Gómez (HIMFG) and State Health Services (Servicios Estatales de Salud).

6.2. Educational component at the community level

The target populations of this component are pregnant women between the fifth and eighth month of gestation and children between 1 and 36 months of age. The goals of this component are: a) to increase parental knowledge, implement better parenting practices and identify alarm signals; (b) to increase the quality of time spent in child care through stimulating behaviors; (c) to improve the motor development of children (gross and fine motor), cognitive (cognition and language) and social-emotional (attachment and adaptive behaviors); and (d) to strengthen the actions of “healthy pregnancy” and “healthy-child programs”.

During 2014, through a collaborative agreement between the CNPSS and the HIMFG for the creation of a curriculum and methodological proposal, 74 community workshops on parenting practices and child development issues were developed. These were validated by an international panel of experts. In 2015, the first study began including prenatal stimulation in Latin America. This study is currently undergoing in two Mexican states and includes pregnant women on the fifth through eighth month of pregnancy with the purpose of examining the impact the workshops have on infant development and the bonding of pregnant mothers, also evaluating which of the proposed schemes would be feasible to operate in the health services facilities. In 2016, an evaluation study for a children’s workshop from the first month of life will be initiated.

7. Actions of the Medical Insurance XXI Century (SMSXXI)

Unlike the PROSPERA program, which provides health services to 1.4 million children who are beneficiaries, the SMSXXI provides coverage to 5.69 million children <5 years of age without any type of social security insurance, financing their complete and comprehensive medical care. This financing provides medical attention for diseases at the second level of care and the problems most commonly associated with childhood developmental delay such as infantile cerebral palsy, hemiplegia and quadriplegia, bilateral sensorineural hypoacusia, cochlear prosthetics implantation, verbal auditory rehabilitation, among others.

This guarantees the possibility of treatment and rehabilitation to the entire population covered by PROSPERA and State Health Services.

Since 2015, according to number 5.3 of its Rules of Operation, the SMSXXI incorporated economic support to carry out the evaluation of childhood development with the application of a screening test and, for those >16 months of age who so require, the application of a diagnostic test. Management of the children will be done through an early stimulation program.24 Incorporation of the screening test to the operation rules of the SMSXXI will allow that the actions described in the component of Detection and Timely Care of PRADI could benefit the entire population by transferring resources to the National Center of Health for Childhood and Adolescence (CeNSIA) for its implementation in the 32 federal entities.

8. Areas of opportunity

High-quality interventions during early infancy, in addition to promoting skills and attacking inequality from its origin, have the highest rate of return of any intervention, being up to $7 dollars per each dollar invested.25 In the long term, the level of childhood development reached in the first years is a determinant of the educational progress in developed countries,26 of school performance in adolescence27 and, in adulthood, could favor a lower index of criminality25 and reduce the prevalence of risk factors for cardiovascular and metabolic diseases.28 In addition, failure of children to reach their maximum developmental potential along with absence of an adequate educational level play a significant role in the intergenerational transmission of poverty.10

The construction of a solid foundation for healthy development during the first years of life is a fundamental requirement, both for economic productivity as well as for successful communities and harmonious civil societies.29 To invest in an equitable manner during the earliest ages means to ensure the same development opportunities for children and adolescents, thus preventing future inequities.30

From an international perspective, it has been shown that money directed towards early childhood is not an expense but rather an investment, if and when it is directed to high-quality programs. The only way to ensure that these have a real impact is with the generation of evidence through research that allows demonstrating the effectiveness of the interventions, monitoring the implementation process and evaluating the results within the population for which they were developed.

In the last 3 years, the per capita investment in childhood development in the component of Detection and Timely Care for beneficiaries of PROSPERA increased by 445% for the implementation of actions evidenced by scientifically documented results,18 being $244.80 MN in 2015. The pilot study to assess the impact of the workshops of the educational component at the community level in pregnant women is in progress. The evidence gathered through this study will support the decision of whether to introduce these workshops to the entire PROSPERA population. Also, as part of this component, we designed a study to assess the impact of community workshops provided to mothers and their children from the first month of life and up to 36 months to determine their usefulness and to establish the groundwork for possible implementation as part of a public policy. Together this will allow offering, with a focus on rights, the promotion of child development and its quality care for all children <5 years of age in Mexico.

Funding

This paper was financed with resources provided by the Convenio CPSS/ART.1°/023/2013 between Hospital Infantil de México Federico Gómez (HIMFG) and the Comisión Nacional de Protección Social en Salud (CNPSS).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Coordinación Nacional de PROSPERA Programa de Inclusión Social (Paula Angélica Hernández Olmos, Hugo Erick Zertuche Guerrero); to Hospital Infantil de México Federico Gómez (César Iván Baqueiro Hernández, Evelyne Rodríguez Ortega, Jessica Guadarrama Orozco, Hortensia Reyes Morales, Elías Hernández Ramírez, Ana Alicia Jiménez Burgos, Marta Lia Pirola, Rocío del Carmen Córdoba García, Beatriz Romo Pardo, Silvia Liendo Vallejos, Socorro De la Torre); to CeNSIA (Ignacio Villaseñor Ruíz, Verónica Carrión Falcón, José de Jesús Méndez de Lira, Diana Araujo, María Magdalena Solares Llamas); Inter-american Development Bank (Caridad Araujo, Ricardo Pérez Cuevas); and to the Régimen Estatal de Protección Social en Salud, Coordinaciones Estatales de PROSPERA of the 32 federal entities, as well as to the staff and psychologists of the Estrategia de Desarrollo Infantil (PROSPERA) and to the personnel of the Programa de Atención a la Salud de la Infancia y la Adolescencia.

Received 20 October 2015;

accepted 22 October 2015

* Corresponding author.

E-mail:antoniorizzoli@gmail.com (A. Rizzoli-Córdoba).