Introducción: El síndrome de cascanueces causado por la compresión de la vena renal izquierda entre la aorta y la arteria mesentérica superior es una causa no glomerular de sangrado renal y varicocele izquierdos. También ha sido reconocido como una causa importante de proteinuria ortostática.

Caso clínico: Adolescente masculino de 17 años de edad con un cuadro de hematuria recurrente. En el examen físico se observó varicocele izquierdo. Índice de masa corporal de 16.3 kg/m2. El examen de orina mostró hematuria y proteinuria masiva. La biopsia renal evidenció proliferación mesangial glomerular leve. El estudio de cistoscopia mostró el origen de la hematuria en el uréter izquierdo. La ultrasonografía Doppler y la angiotomografía de contraste revelaron velocidad pico de la vena renal izquierda de 20 cm/s, relación del índice de flujos de la vena renal izquierda de su porción aortomesentérica e hiliar de 7.7 y agrandamiento de la vena renal izquierda en la porción hiliar. Con el diagnóstico de síndrome de cascanueces se decidió proporcionar tratamiento conservador. En los meses siguientes mostró disminución importante de los episodios de hematuria recurrente, y se observó remisión de las manifestaciones clínicas y de las alteraciones en el examen de orina. A los 13 meses de evolución el índice de masa corporal fue de 19 kg/m2.

Conclusiones: Este caso clínico muestra la relación entre el incremento en la masa corporal y la remisión del síndrome de cascanueces manifestado como presencia de varicocele izquierdo, hematuria y proteinuria graves. Los síntomas desaparecieron al incrementar el índice de masa corporal, probablemente debido a un aumento en la grasa retroperitoneal que mejoró el ángulo aortomesentérico de la vena renal izquierda.

Background: Nutcracker syndrome caused by compression of the left renal vein between the aorta and superior mesenteric artery is a non-glomerular cause of left renal bleeding and left varicocele. It has also been recognized to be an important cause of orthostatic proteinuria.

Case report: A 17-year-old male was evaluated due to recurrent macroscopic hematuria. Physical examination showed left varicocele. Body mass index was 16.3 kg/m2. Urinalysis demonstrated hematuria and massive proteinuria. Renal biopsy showed mild mesangial glomerular proliferation. Cystoscopy showed hematuria originating from the left ureter. Doppler ultrasonography and contrast-enhanced computed angiotomography revealed a peak velocity of the left renal vein of 20 cm/s, ratio of peak velocity of aortomesenteric and hilar portions of left renal vein of 7.7 and enlargement of the left renal vein in the hilar portion. With a diagnosis of nutcracker syndrome, the patient received conservative treatment. During follow-up, progressive remission of the recurrent episodes of hematuria and proteinuria was observed. The patient had no clinical symptoms or abnormal urinalysis. At 13 months of follow-up the body mass index was 19 kg/m2.

Conclusions: This case shows the relationship between the increase in body mass index and remission of nutcracker syndrome, manifested as left varicocele, hematuria and massive proteinuria. All symptoms disappeared with the increase of body mass index, probably due to increase in retroperitoneal fat with improvement of the aortomesenteric angle of the left renal vein.

1. Introduction

Nutcracker syndrome is characterized by the extrinsic compression of the left renal vein, which prevents its normal blood drainage in the inferior vena cava. In the majority of patients it is produced by compression of the left renal vein between the aortic artery and superior mesenteric artery. This variant has been called anterior nutcracker syndrome. Less frequently, the left renal vein is found to be in the retroaortic position; therefore, compression between the aorta and the vertebral body occurs. This variant is referred to as posterior nutcracker syndrome.1-3

The characteristic clinical manifestation is hematuria, which may be microscopic or, more commonly, macroscopic, especially after remaining in the standing position or after exercise. Other manifestations include orthostatic proteinuria, the combination of hematuria and proteinuria, pain in the pelvic region, and left varicocele.4-7

We present the case of an adolescent with nutcracker syndrome mainly manifested as recurrent episodes of hematuria and proteinuria.

2. Clinical case

We present the case of a 17-year-old male with hematuria and proteinuria. He was referred for medical consultation in order to rule out glomerular disease. He presented with repeated episodes of hematuria for 8 months before admission without additional symptoms at the beginning. Four months later symptoms of fatigue and severe skin pallor were added. He was seen at another institution where severe anemia was documented (hemoglobin of 5.5 g/dl), for which management with IV iron and blood transfusions was indicated.

On questioning the patient, he reported having had a weight loss of ∼6 kg in the last year without apparent reason prior to the initiation of the clinical manifestations. There was no significant family, pathological or environmental history for the current problem. On admission he weighed 45.7 kg (percentile <3%), height 167 cm (percentile 13%), body mass index (BMI) 16.3 kg/m2, blood pressure 115/76 mmHg. On physical examination a left varicocele was noted.

Results of the laboratory studies were as follows: blood count showed hemoglobin of 14.2 g/dl, hematocrit 44%, reticulocytes 4%, microcytosis (+) and hypochromia (+); normal coagulation times; creatinine 0.8 mg/dl, urea nitrogen 15 mg/dl, uric acid 5.2 mg/dl, calcium 8.7 mg/ dl, phosphorus 4.4 mg/dl, magnesium 1.9 mg/dl, sodium 140 mmol/l, potassium 3.6 mmol/l, chloride 104 mmol/l; glucose 77 mg/dl. Total proteins were 7.5 g/dl, albumin 4.2 g/dl; cholesterol 137 mg/dl, triglycerides 60 mg/dl. Liver function tests were normal. Immunological studies were negative and included anti-DNA, anticardiolipin, c-ANCA, p-ANCA, rheumatoid factor and direct Coombs; C3 90.4 mg/ dl, C4 13.7 mg/dl.

Urine studies reported the following results: urinalysis– pH 6, density 1.030, albumin (+++), hemoglobin (++++), erythrocytes (too many to count), calcium/creatinine ratio 0.03; proteinuria in nighttime collection of 12 h, 115 mg/ m2/h; proteinuria/creatininuria ratio: 1.25.

Tuberculosis, BAAR, PPD and Mycobacterium tuberculosis culture were all reported with negative results. Renal ultrasound study showed kidneys of normal size for age without images of stones, cysts or ectasia.

Due to the presence of hematuria and proteinuria, a percutaneous renal biopsy was performed. It demonstrated 12 glomeruli: one with global sclerosis and the remaining with slight proliferation of the mesangium glomerular. There were no other alterations. No tubulointerstitial or vascular lesions were seen. Glomerular immunofluorescence study was negative.

During hospitalization, the patient presented a persistent macroscopic hematuria, occasionally with clots. Because of this situation it was considered that the patient had a persistent hemorrhage of the kidney or urinary tract; therefore, studies were directed to determining the cause of the hemorrhage.

Upon performing a cystoscopy it was observed that the hemorrhage came from the left kidney. Renal scan with labeled red blood cells showed a mild hyperemia of the left kidney compared to the right.

New renal ultrasonography showed the left renal vein with a flow of 20 cm/sec compared with the right renal vein (25.9 cm/sec). On measuring the flow rate between the aortomesenteric portion and the hilar portion of the left renal vein a value of 7.7 was observed.

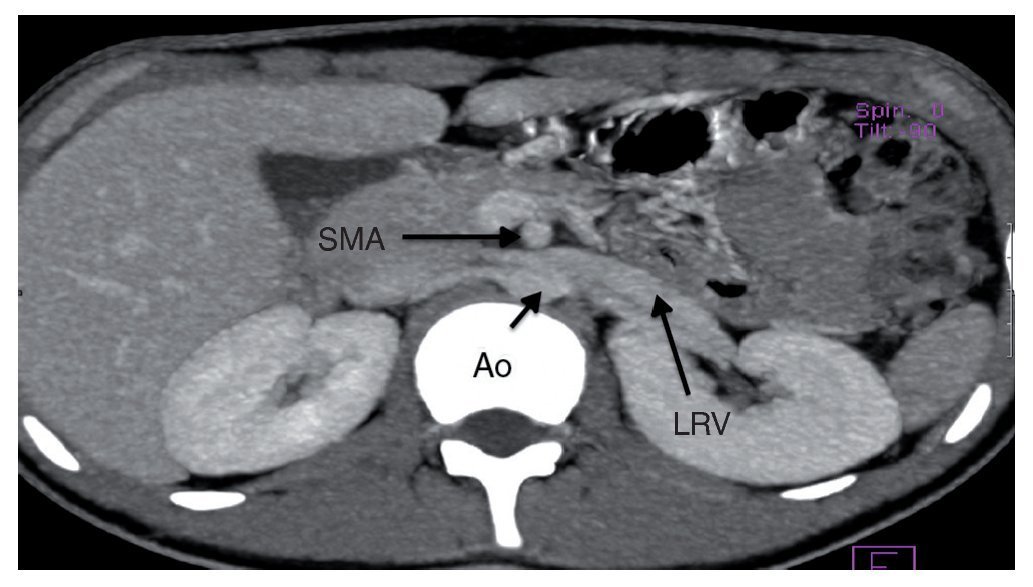

Angiography study of the kidney and arterial and venous vessels showed an increase in the diameter of the left renal vein at its distal portion (Fig. 1). No indirect data of obstruction were seen in the second portion of the duodenum. With the diagnosis of nutcracker syndrome and the age of the patient, it was decided to maintain surveillance of the progression of the hematuria and proteinuria without carrying out any surgical intervention. Treatment with folic acid and ferrous sulfate was indicated. It was recommended that the patient increase his caloric intake and to maintain an adequate intake of protein so as to improve his nutritional status.

Figure 1 Renal angiotomography. Increase in the diameter of the left renal vein is observed. SMA, superior mesenteric artery; Ao, aorta; LRV, left renal vein.

During the 6-month follow-up visit after his admission, he reported spacing of the episodes of painless macroscopic hematuria, which was present especially after physical exercise. At this time his serum creatinine remained with values of 0.8 mg/dl and urinalysis results were pH 7, density 1.010, albumin (+) and hemoglobin (+++). At this time, treatment was indicated with low-dose enalapril (2.5 mg/12 h).

A new ultrasound study was performed and showed a decrease in the index of the aortomesenteric and left renal vein hilar segments of 5.1. This indicated an increase in the distal flow of the left renal vein with respect to the previous values. Also, on physical examination the BMI was shown to be increased to 17.8 kg/m2.

Three months later the patient was found to be asymptomatic without evidence of episodes of hematuria during this time. General urinalysis showed a pH of 6, density 1.015, without proteinuria or hematuria. It was decided to discontinue the enalapril and continue treatment with ferrous sulfate.

At the patient’s last follow-up 4 months later (13 months after his admission), he reported no new episodes of macroscopic hematuria in the last 7 months. Blood studies showed hemoglobin of 16.8 g/dl, hematocrit 49.7%, mean corpuscular volume and mean corpuscular hemoglobin as normal. Urine test did not show any proteinuria or hematuria. BMI of 19 kg/m2 was documented.

3. Discussion

It has been proposed that nutcracker syndrome occurs as a consequence of the abnormal course of the left renal vein, which is found in an area higher than usual or an anomalous branching of the superior mesenteric artery on emerging from the aorta.1

The age of the patients could vary, from childhood up to the seventh decade of life, although the majority of the patients present clinical manifestations during the second or third decades of life, as occurred in the patient presented here.

In this patient, diagnosis of nutcracker syndrome was established based on the clinical manifestations of a recurrent macroscopic hematuria and even persistent between some episodes of the recurrence, demonstration of the hematuria coming from the left ureter, left varicocele, and findings on ultrasonography and angiotomography studies.

The episodes of hematuria corresponded to conditions classified as hemorrhage because they were accompanied by the presence of clots and not as glomerular hematuria where red blood cylinders are seen in place of clots (not present in the urine of this patient). Due to the presence of concomitant hematuria and proteinuria, it was decided to perform a percutaneous renal biopsy that showed mild proliferation of the glomerular mesangium and normal tubulointerstitial area. It has been considered that in nutcracker syndrome, as a consequence of the increase in the retrograde pressure in the left renal venous system, thin-walled varicose veins are formed in the renal pelvis and whose rupture produces episodes of hemorrhage characteristic of this disorder.7 Cystoscopy also demonstrated bloody urine coming from the left side of the ureter.

During follow-up the patient reported that the episodes of macroscopic hematuria occurred especially after exercising. In this regard, it has been postulated that in the standing position there is visceral proptosis, which stretches even more the angle between the superior mesenteric artery and the aorta, thus increasing the hemodynamic response characteristic of this syndrome.2

Episodes of hematuria were accompanied by proteinuria in a nephrotic range (proteinuria is considered in a 12-h nighttime urine collection at a nephrotic range with a value of >40 mg/m2/h) but without concomitant hypoalbuminemia or hyperlipidemia. The latter has also been explained by the increase in pressure on the left renal vein associated with an increase in the release of norepinephrine and angiotensin II, induced by modifications in the renal hemodynamics during standing or with exercise.2,8

Other clinical manifestations of the nutcracker syndrome include abdominal or left flank pain that occasionally radiates to the thigh or gluteus region and is exacerbated with the sitting position, standing position or with exercise.1 Also a left varicocele may be observed in up to 5-9.5% of male patients.1,9 The patient studied had a left varicocele, asymptomatic up to the time of his last follow-up visit. Varicocele is caused by the increase in pressure of the left renal vein as a consequence of the obstruction that causes a retrograde flow of this vein towards the left spermatic vein.10

Renal biopsy of the patient studied presented mild glomerular mesangial proliferation, with negative immunofluorescence test for all the reactants. The proba bility that the mesangial proliferation is caused by the orthostatic macromolecular overload has been postulated, with accentuated alteration of the glomerular microcirculation increased by the effect of angiotensin II.8

This patient presented weight loss in the last year prior to the appearance of the episodes of recurrent hematuria. In this regard, in some studies it has been observed that low BMI is positively correlated with the nutcracker syndrome and that clinical manifestations may present themselves after weight loss.1 In this sense, it has been postulated that the reduction in the retroperitoneal fat content can further reduce the aortomesenteric angle and induce the clinical manifestations of nutcracker syndrome.1

These considerations may explain why the patient’s clinical symptomatology improved as his BMI improved because it has been speculated that aortomesenteric compression of the left renal vein could improve with physical development, especially increase of BMI in children.11,12

It has been recommended that in all children with persistent or recurrent hematuria of unknown origin that renal Doppler ultrasound study be performed.13 In regard to the renal ultrasound results, Shin et al. reported a study of 15 children with nutcracker syndrome and compared the peak velocity by Doppler ultrasound examination in 15 healthy children. These authors found that in the proximal or hilar portion of the left renal vein in children with nutcracker syndrome the peak velocity was on average from 21.99 ± 5.47 cm/sec, whereas in the control group the average value was 27.18 ± 5.34 cm/sec. Similarly, when examining the relationship between the flow velocities of the aortomesenteric portion and the hilar portion of the left renal vein, a value of >4.8 was observed in almost all children with nutcracker syndrome.12

This has been interpreted in the sense that the compression of the left renal vein between the superior mesenteric artery and the aorta causes dilation of the left renal vein in its distal or hilar portion and reduction of the peak velocity in this venous portion.12 A peak velocity of 20 cm/sec was observed in the distal portion of the left renal vein in the patient studied (less than that observed in the right renal vein), which was probably due to the proximal obstruction of the left renal vein. Also, the ratio between the flow velocities of the aortomesenteric portion and the hilar portion of the left renal vein was greater than the cut-off value established by Shin et al.12

The findings of the angiotomography were inconclusive because, although an increase of the left renal vein diameter at its distal portion was observed, the attempts to validate the normal diameter of the left renal vein at its distal portion have not been successful because dilation of the left renal vein could be a normal variant.1

Management of nutcracker syndrome can be divided into conservative treatment and interventional or surgical management.

Although the natural history of the nutcracker syndrome has not been clearly defined, its spontaneous resolution has been reported in children, sometimes after several years of persistence.11,14

In young patients (<18 years of age) conservative treatment is recommended. In this respect it has been observed that with physical development the fatty and fibrous tissue deposit increases in the origin of the superior mesenteric artery, which could attenuate compression of the left renal vein. On the other hand, changes can occur on the associated vascular anatomic proportions with body growth.1 In addition, formation of collateral veins may favor the decrease in pressure in the left renal vein.2

It has also been reported that administration of an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor may improve the orthostatic proteinuria associated with nutcracker syndrome which, as mentioned, probably depends on the increased action or release of angiotensin II.8 The patient studied here received treatment with enalapril, an ACE inhibitor, for a short time, so it is not possible to evaluate its beneficial effect on the progression of the clinical picture.

On the other hand, when symptoms of hematuria and proteinuria become worse during the period of observation for conservative management (6-24 months), the indication for a surgical intervention and interventional should be considered, even if the patient is <18 years of age. Treatment methods include placement of a stent in the stenosed zone of the left renal vein to surgical procedures for transposition of the left renal vein to a more distal portion of the inferior vena cava or the transposition of the superior mesenteric artery, bypass of the left renal vein and anastomosis to the inferior vena cava and renal autotransplant.2,15-17

Ethical disclosures

Protection of human and animal subjects. The authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Confidentiality of Data. The authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consent. The authors must have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects mentioned in the article. The author for correspondence must be in possession of this document.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest of any nature.

Received 28 August 2014;

accepted 2 October 2014

* Corresponding author.

E-mail:velasquezjones@hotmail.com (L. Velásquez-Jones).