Introducción: Las malformaciones linfáticas se originan a partir de malformaciones de los vasos linfáticos durante el periodo embrionario, lo que condiciona sus características histopatológicas, el calibre de los vasos que lo componen, así como el sitio donde se localizan.

Caso clínico: Se presenta el caso de un paciente masculino de un año 2 meses de edad, quien se diagnostica con una malformación linfática localizada en el omento menor. Esta localización es una de las menos frecuentes en este grupo de malformaciones.

Conclusiones: Se expuso el abordaje diagnóstico y la resolución quirúrgica de una malformación linfática del omento menor, con resección completa del mismo, sin recidivas ni complicaciones.

Introduction: Lymphatic malformations are caused by malformations of the lymphatic vessels during embryonic life, conditioning their histopathological characteristics, the caliber of the vessels that compose it, and the site where they are located.

Case report: We report the case of a male patient of 1 year and 2 months old who was diagnosed with a lymphatic malformation located in the lesser omentum, this localization being one of the least frequent of this group of malformations.

Conclusion: We describe the diagnostic approach and surgical resolution of a lesser omentum lymphatic malformation with its complete removal and without complications or recurrence.

1. Introduction

Vascular malformations represent a group of diseases affecting 0.5% of the population. This group of diseases is called "vascular anomalies."

One of these anomalies is lymphangioma. It was described for the first time by Redenbacher in 1828.1 However, it was not until 31 years ago when Mulliken and Glowacki described the problem that these diseases were mistakenly called "angiomas." For this reason, they proposed in 1982 a new classification based on biological criteria and clinical behavior. It was adopted by the International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies.2

Its origin is not well elucidated. Mechanisms of lymphatic system development during the embryonic period are unknown. A theory remains of a failure at the communication level between the lymph vessels during intrauterine life. The majority of these malformations manifest themselves and diagnosis is made during the early stages of life as well as the most common sites of their appearance.3

Of the lymphatic malformations, 95% are located in the neck and the axilla, whereas the remaining 5% have an intraabdominal presentation and are found in the mesentery, omentum, or retroperitoneum. In addition, these are rare malformations.4,5

Currently, vascular anomalies are classified into two groups. The first corresponds to vascular tumors and the second to vascular malformations. The latter are subclassified according to their flow management: high, low or if there are combinations. Lymphatic malformations are found among the low flow vascular malformations.6,7

2. Clinical case

We present the case of a 2-year-old male patient born at term after normal labor with a birth weight of 3600 g and Apgar 9/9. He was the product of a normal pregnancy with deficient prenatal care, no obstetric ultrasounds, and no iron supplements, folic acid or multivitamins. The patient showed normal psychomotor development.

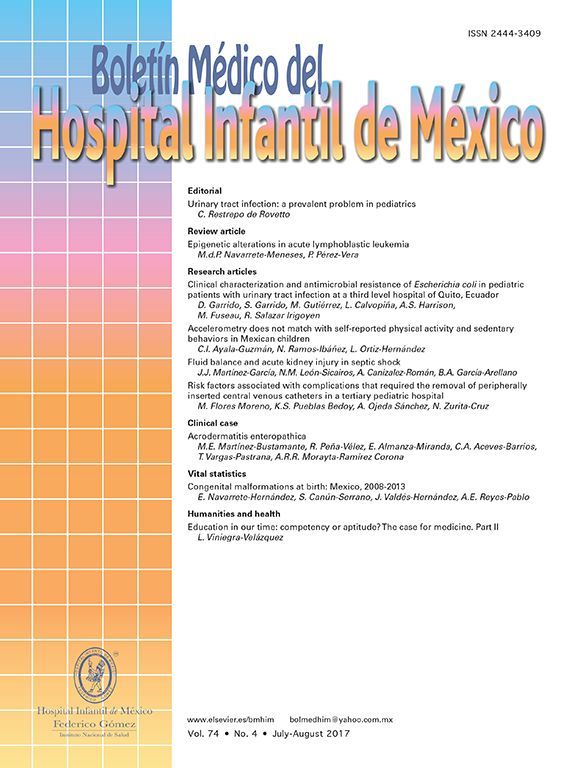

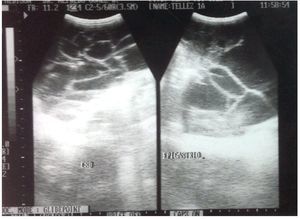

His disorder began 6 months previously with rejection of food and abdominal distention. He was taken to a health center where he was prescribed iron and vitamins A, C and D. In the last month there was the appearance of greenish liquid stools with mucous. He was given oral electrolytes and his condition improved. His primary care physician requested laboratory studies that reported microcytic and hypochromic anemia. Abdominal ultrasound also reported a multilobular intraabdominal cystic mass extending to both paracolic gutters and pelvic cavity. The kidneys, liver and gallbladder were reported to be normal (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. High-resolution study with convex transducer. Anechoic, multitrabecular image of ∼12.2 × 6.8 cm was observed.

The patient was admitted to the Hospital Regional Dr. Valentín Gómez Farías for study, diagnosis and treatment. Upon admission to the Pediatric Intensive Care Service he was observed to be active, reactive, normally hydrated, pale skin, distended soft, depressible abdomen with decreased peristalsis, telangiectasias in the abdominal wall with no data of peritoneal irritation.

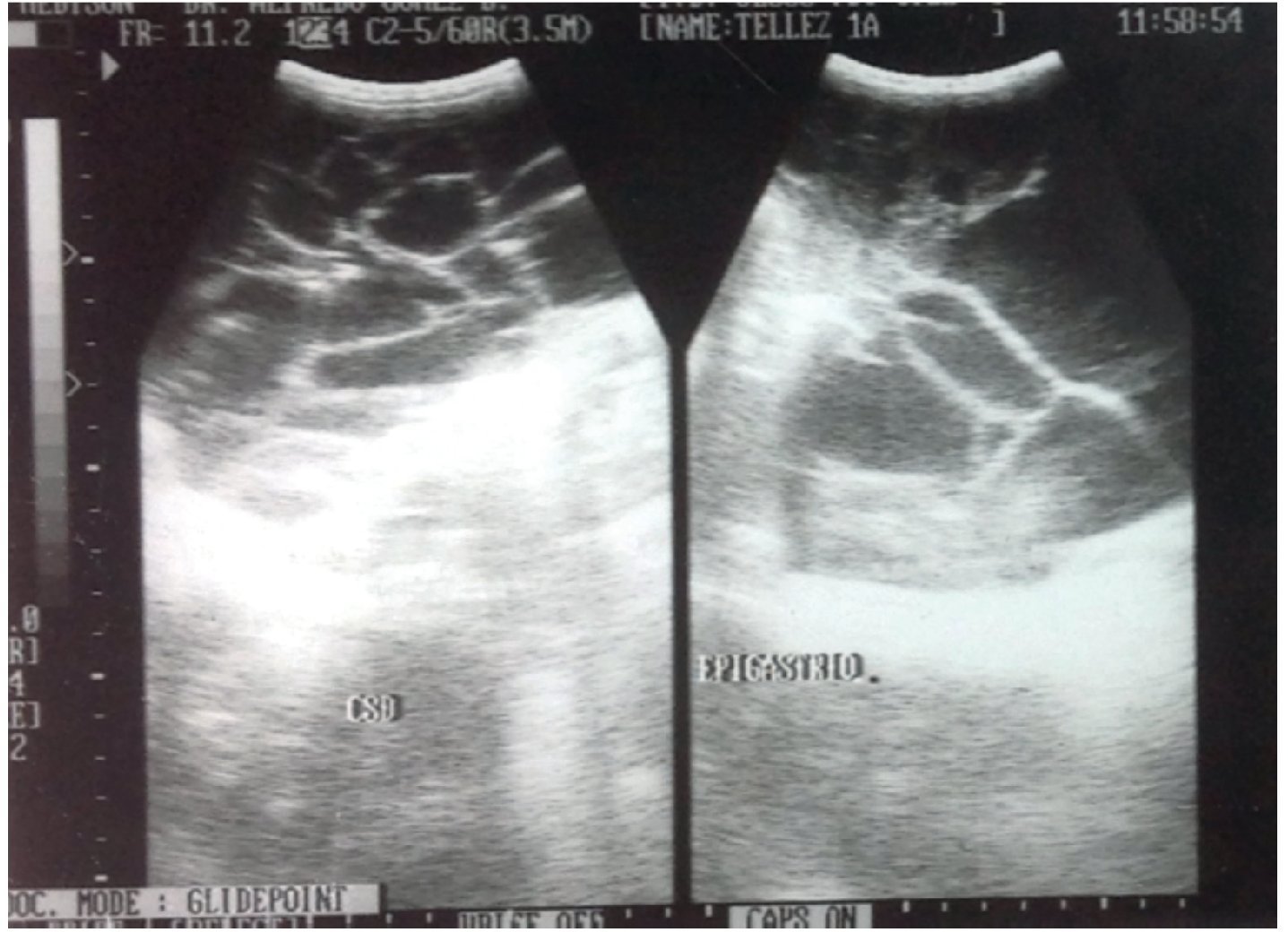

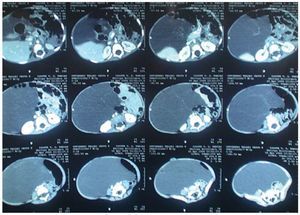

During his hospitalization, new laboratory studies were requested with the following results: hemoglobin 12.3 g/dl, hematocrit 37.6 %, mean corpuscular hemoglobin 24.6 pg, mean corpuscular volume 75.5 fl, leukocytes 123,000/mm3, platelets 503,000/mm3, glucose 103 mg/dl, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 36.7 IU/l, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 20.8 IU/l, alkaline phosphatase 218 IU/l, lactate dehydrogenase 573 IU/l, carcinoembryogenic antígen 1.8 μg/l, hCG 0.100 mIU/ml, a-fetoprotein 5.0 IU/ml, CA 125 31.6 IU. Abdominal CAT reported a multilobulated cystic mass that displaced the bowel loops anteriorly and towards the left (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Computed axial tomography of abdomen. Multilobular cystic mass is observed, which moves an teriorly and displaces intestinal loops to the left.

The patient was evaluated by the Pediatric Surgery Service and it was decided to carry out an exploratory laparotomy and resection of the cystic mass. The procedure was carried out under general anesthesia using a midline supra- and infraumbilical incision by tissue planes up to the abdominal cavity (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Exterior habitus of the patient preoperatively.

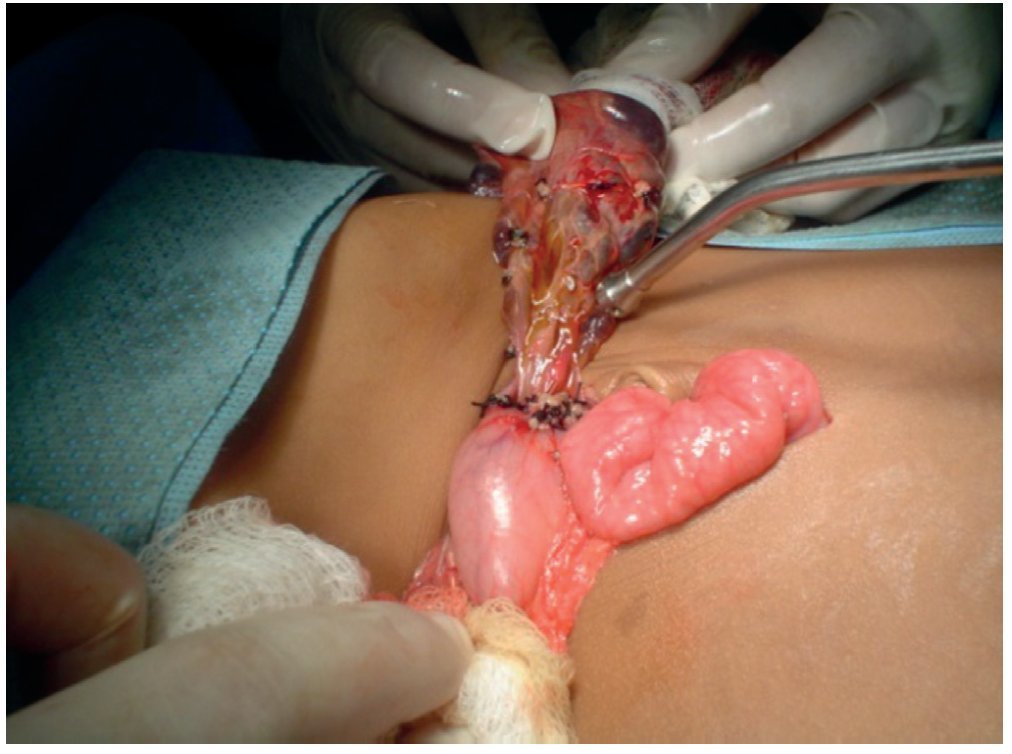

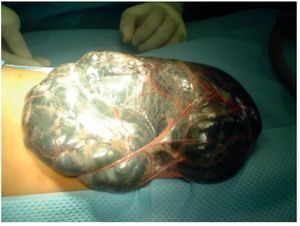

A lymphatic malformation with multiple cysts >5 cm was identified. There was lymphatic fluid within its interior without evidence of blood, originating from lymphatic vessels of the lesser curvature of the stomach and lesser omentum (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Lymphangiomatous tumor totally covering the exterior of the abdomen.

Complete exposure of the tumor was carried out, identifying its origin. Blunt dissection of its base was done, cutting and ligating its vessels throughout the lesser curvature of the stomach (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Lymphangioma pedicle in the lesser omentum.

The fluid content of the tumor was ∼500 ml with an estimated blood loss for the procedure of 10 ml. A 100% resection was done without evidence of residual microscopic evidence of the malformation. Subsequently, a major omentectomy was done and closure of the abdominal wall was done by tissue planes. The patient was transferred to the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit with stable vital signs.

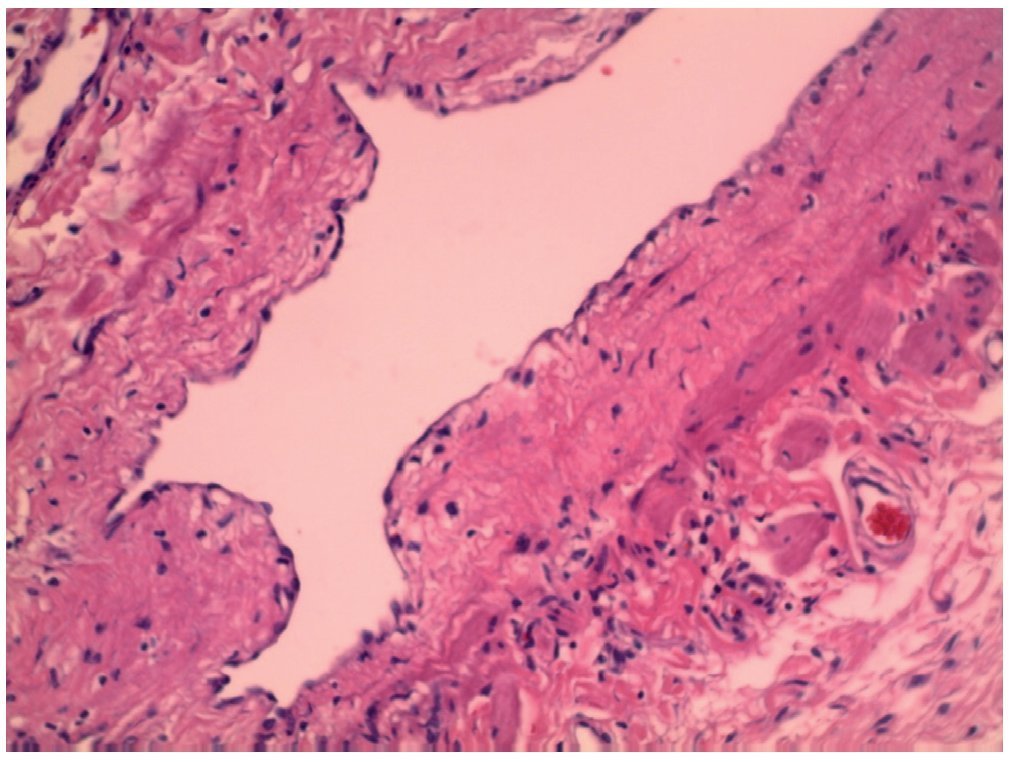

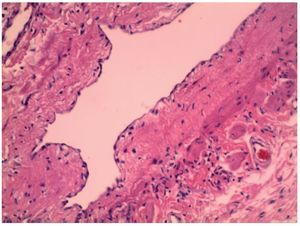

Postoperatively, the patient had baseline blood tests performed. Results were hemoglobin 7.87 g/dl and hematocrit 22% and blood transfusion was decided upon. After 4 postoperative days, the patient was discharged in improved condition. Histopathological report was a benign proliferation of lymphatic vessels immersed in connective tissue, compatible with a lymphatic malformation (Fig. 6).

Figure 6. Section of lymphatic duct shown with hematoxylin and eosin stain.

3. Discussion

Lymphatic malformations are more frequent in males, with a gender ratio of 3:2. The most frequent abdominal location in the pediatric age is in the mesentery in 45% of the cases followed by omentum, mesocolon, and retroperitoneum.7 These malformations may present macro-or microcystic mostly lobulated characteristics with lymphatic and/or hemorrhagic content. Lymphatic malformations tend to occur in lax tissues where they can expand and create large cystic spaces.8 They may present as inflammatory myxoid, hemorrhagic or ischemic and granulated tissue.9

The patient began with a clinical picture of abdominal distention and rejection of food, which is characteristic in 80% of the cases of abdominal lymphatic malformations. In these malformations one can see complications due to compression of adjacent structures by the lymphatic malformation. Some of these are pyelonephritis due to ureteral obstruction, acute abdomen due to infection of the malformation, icterus and anemia due to hemorrhage in the malformation, and hemoperitoneum due to rupture.5 From the evolution of his symptomatology, the patient had a microcytic-hypochromic anemia, which is an uncommon complication of lymphatic malformations. Although the patient's nutritional deficits were unknown, these types of associated anemias are well described in the literature, whether due to its interaction with adjacent organs such as the intestine, which can cause gastrointestinal tract bleeding or due to intrinsic chronic blood loss.10

Ultrasound, computerized axial tomography (CAT) and nuclear magnetic resonance are used for the diagnosis of lymphatic malformations. In this case, with ultrasound and abdominal CAT a multilobular cystic mass was found that extended to both paracolic gutters and pelvic cavity. In the majority of ultrasound studies performed in patients with lymphatic malformations a hypoechoic mass with septa in its interior is visualized. CAT is useful in seeing the extension and effect of other structures and evaluates whether the tumors are intraperitoneal and with certain characteristics such as internal heterogeneity, fat density, cystic formation and calcifications, which provides an idea as to the benign degree of the tumor.11

Prenatal ultrasound is a useful tool that offers the advantage of being able to identify the lesion, monitor its growth and its relationship with adjacent organs. It is postulated that these malformations appear from the 6th week of gestation and are characterized by a multiseptated hypoechoic image with thin walls and variable dimensions. Survival is dependent on the involvement of adjacent organs and management of labor. The majority of the series describe a survival that does not go >20% without there being an effective treatment to date.12,13

With respect to the treatment of abdominal lymphatic malformations, almost all authors recommend complete excision of the malformation. Although it is a benign process, due to its abdominal location it may be locally invasive. Complete removal is not always possible; therefore, it is associated with a high rate of recurrence, complications and morbidity. If a vital organ is affected, marsupialization of the internal cavity may be an acceptable alternative. There are isolated reports of treatment of abdominal lymphatic malformations with sclerosing substances such as OK-432 (picibanil), although it specific use is more acceptable in lesions with a cervical location. For this reason, its application in these types of lesions is not yet completely defined.14 Other therapeutic strategies such as image-guided aspiration and percutaneous drainage of lymphatic malformation have been carried out with good results, although with little experience. These malformations tend to be radio-resistant and do not respond to systemic or intralesional corticosteroids.15,16 Laparoscopic techniques should be taken into consideration for the treatment of selected cystic lesions with intraabdominal or retroperitoneal location. In our opinion, complete removal of the entire mass constitutes a safe and successful therapeutic option for this type of patient.

Without adequate treatment, lymphatic malformations have a high rate of recurrence. Our patient, at 5 years of evolution after surgical resection, has not demonstrated any recurrence or complications.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest of any nature.

Received 25 July 2013;

accepted 19 December 2013

* Corresponding author.

E-mail:falcon_domenech@hotmail.com (J.A. Fernández Domenech).