Introducción: La prueba Evaluación del Desarrollo Infantil (EDI), diseñada en México, clasifica a los niños de acuerdo con su desarrollo en desarrollo normal, rezago en el desarrollo y riesgo de retraso. La versión modificada se desarrolló y validó, pero no se conocen sus propiedades en base poblacional. El objetivo de este trabajo fue establecer la confirmación diagnóstica en niños de 16 a 59 meses identificados con riesgo de retraso por la prueba EDI.

Métodos: Se realizó un estudio transversal de base poblacional en una entidad federativa de México. Se aplicó la prueba EDI a 11,455 niños de 16 a 59 meses, de diciembre de 2013 a marzo de 2014. Se consideró como población elegible al 6.2% (n = 714) que obtuvo como resultado riesgo de retraso. Para la inclusión en el estudio se realizó una aleatorización estratificada por bloques para sexo y grupo de edad. A cada participante se le realizó la evaluación diagnóstica utilizando el Inventario de Desarrollo de Battelle 2a. edición.

Resultados: De los 355 participantes incluidos, el 65.9% fue de sexo masculino y el 80.2% de medio rural. El 6.5% fueron falsos positivos (cociente total de desarrollo > 90) y el 6.8% no tuvo ningún dominio con retraso (cociente de desarrollo de dominio < 80). Se calculó la proporción de retraso en las siguientes áreas: comunicación (82.5%), cognitivo (80.8%), personal-social (33.8%), motor (55.5%) y adaptativo (41.7%). Se observaron diferencias en los porcentajes de retraso por edad y dominio/subdominio evaluado.

Conclusiones: Se corroboró la presencia de retraso en al menos un dominio evaluado por la prueba diagnóstica en el 93.2% de la población estudiada.

Background: The Child Development Evaluation (or CDE Test) was developed in Mexico as a screening tool for child developmental problems. It yields three possible results: normal, slow development or risk of delay. The modified version was elaborated using the information obtained during the validation study but its properties according to the base population are not known. The objective of this work was to establish diagnostic confirmation of developmental delay in children 16- to 59-months of age previously identified as having risk of delay through the CDE Test in primary care facilities.

Methods: A population-based cross-sectional study was conducted in one Mexican state. CDE test was administered to 11,455 children 16- to 59-months of age from December/2013 to March/2014. The eligible population represented the 6.2% of the children (n = 714) who were identified at risk of delay through the CDE Test. For inclusion in the study, a block randomization stratified by sex and age group was performed. Each participant included in the study had a diagnostic evaluation using the Battelle Development Inventory, 2nd edition.

Results: From the 355 participants included with risk of delay, 65.9% were male and 80.2% were from rural areas; 6.5% were false positives (Total Development Quotient >90) and 6.8% did not have any domain with delay (Domain Developmental Quotient <80). The proportion of delay for each domain was as follows: communication 82.5%; cognitive 80.8%; social-personal 33.8%; motor 55.5%; and adaptive 41.7%. There were significant differences in the percentages of delay both by age and by domain/subdomain evaluated.

Conclusions: In 93.2% of the participants, developmental delay was corroborated in at least one domain evaluated.

1. Introduction

Child development is a process of change in which the child learns to master always more complex levels of movement, thinking, feelings and relationships with others. It occurs when the child interacts with people, things, and other stimuli in their biophysical and social environment and learns from them.1

All child development evaluation processes aim to give an opportunity for parents and professionals to have complete knowledge about the capabilities and limitations of the child so they can be prepared to generate more effective interventional guidelines, find useful answers and generate adequate strategies.2 Detection of developmental problems is of utmost importance because, when identified early, it allows access to timely diagnosis and treatment3 for those children who do not perform age-appropriate activities and recommends actions that allow these children to continue to acquire the skills corresponding to their age.

The Child Development Evaluation or CDE test (Prueba Evaluación del Desarrollo Infantil o EDI in Spanish) is a screening test designed and validated in Mexico for the timely detection of developmental problems for children aged 1-59 months. The results of the test are based on a semaphore system (green - normal, yellow - lag, red - risk of delay). The non-exclusive reasons why a red result or risk of delay in children 5-59 months of age can be obtained are as follow:

1. Not carrying out activities evaluated in the area of the development axis: fine motor, gross motor, language, social and knowledge that correspond to the child’s age group or to the earlier age group.

2. Have at least one alarm sign.

3. Have an alteration in at least one question of the neurological examination axis4.

The modified version of the CDE5 test has a sensitivity of 89% and a specificity of 62% for the group 16-59 months of age6, which reaches >80% if each domain or subdomain for development is analyzed separately;7 93.8% of children with red results have at least one domain with low-normal result and can benefit from a directed intervention8.

After analyzing the available evidence, among the panel of experts “Validation of diagnostic tools for childhood developmental problems in Mexico” it was concluded, among other things, that “the modified version of the CDE test was the most adequate tool in the context of the population<5 years in Mexico”, and that “for children 16-59 months of age who in this test obtained a result of risk of delay it is recommended that they undergo a diagnostic test with the purpose of establishing a profile that can lead to more optimal management and care ”.6-10 The Battelle Developmental Inventory, 2nd edition in Spanish (BDI-2)11 has demonstrated its usefulness by identifying children with lower scores with diagnosis of developmental problems such as global delay in development, Down syndrome, children with history of prematurity12, attention deficit disorder13 and autistic disorder.14 For this reason, in addition to its full availability in the Spanish language, the same panel recommended the BDI-2 as the most appropriate diagnostic tool for the country.9

The main objective of this study was to establish diagnostic confirmation of developmental delay and domains most affected in children 16-59 months of age identified with risk of delay according to the modified version of the CDE test. A secondary objective was to analyze the differences according to gender, age group, nutritional status and type of locality (rural or urban).

2. Methods

A population-based cross-sectional study was carried out in rural and urban areas in the state of Puebla, located in the center of the Mexican Republic.

2.1. Study population

The analyzed study population was comprised of boys and girls from 16–59 months of age identified with risk of developmental delay according to the modified version of the CDE test from December 2013 to March 2014. For each participant the following data were recorded: gender, age (in months), type of residence (rural <2,500 inhabitants)15, level of poverty in the area16, nutritional status based on the weight/height ratio for gender (according to the tables from the WHO17) and for those >3 years of age, if they attend kindergarten.

2.2. Description of the tests given and evaluation criteria

2.2.1. Screening test

The Child Development Evaluation (CDE) is a screening test developed and validated in Mexico for the timely detection of developmental problems in boys and girls from 1 month of age and up to 1 day before the child’s fifth birthday.5,6 The modified version has 26–35 items answered by the primary caregivers or are scored by observation of the presence of behaviors grouped in five axes: a) biological risk factors;

b) alert signs; c) developmental areas (fine motor, gross motor, language, social and knowledge); d) alarm signs; and e) neurological examination. Possible results are normal development (green), developmental lag (yellow) or risk of delay (red). The red classification can be made when a result is obtained in one or more of the following axes: areas of development, neurological examination or signs of alarm4.

2.2.2. Diagnostic evaluation

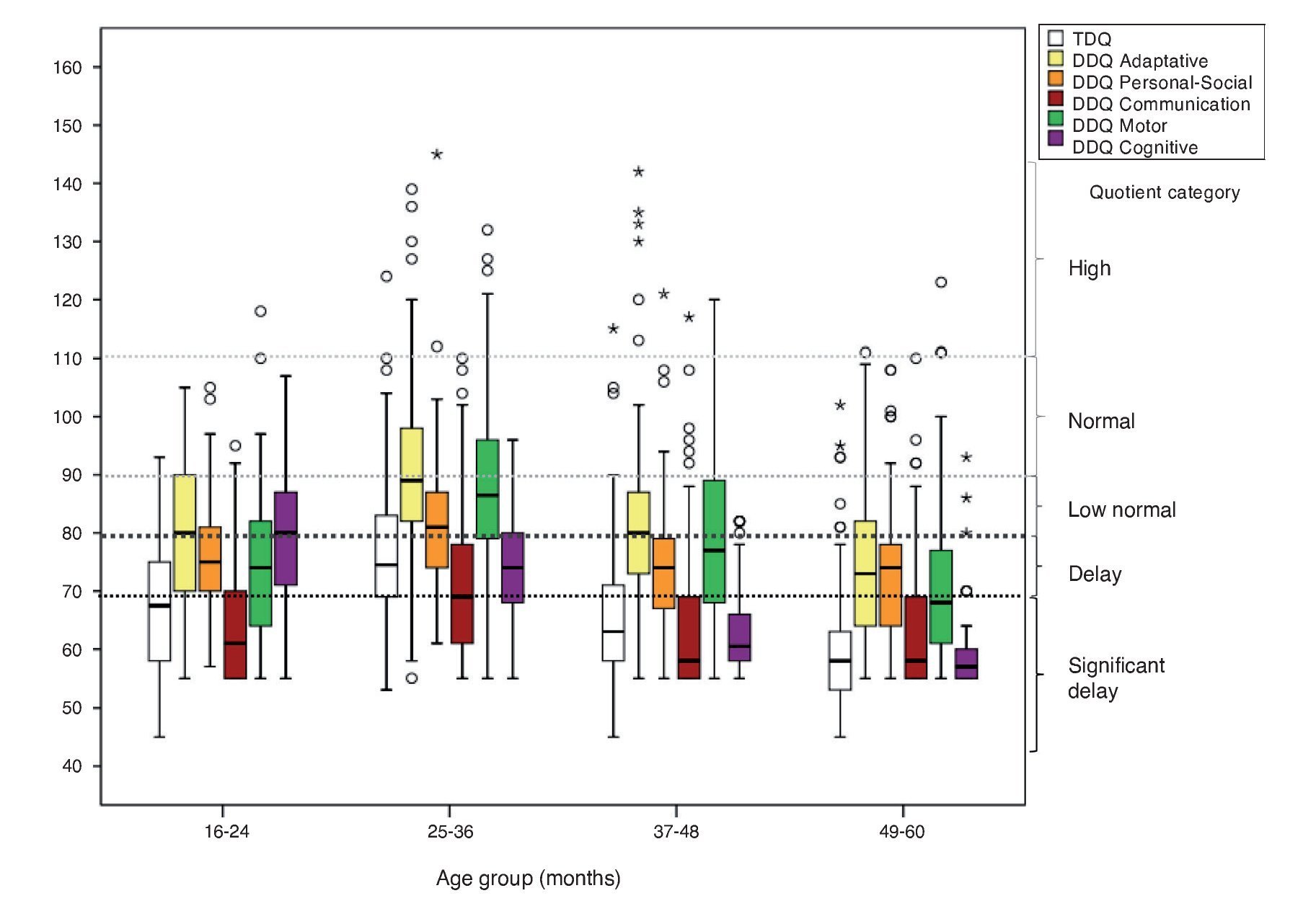

BDI-2 in Spanish11 is a diagnostic test that covers from 0 months up to 7 years 11 months of age and is used to evaluate and quantify childhood development at different levels: global, via a total quotient of development (CTD); domain, by means of coefficient of development for each domain (CDD); or by subdomain by means of a scalar score (SSS).18 The five domains it evaluates are adaptive, personal-social, communication, motor and cognitive. This is done through the evaluation of 13 independent subdomains: self-care, personal responsibility, adult interaction, peer interaction, self-concept and social role, receptive and expressive communication, gross motor, fine motor and perceptual, attention and memory, perception and concepts and reasoning and academic skills.

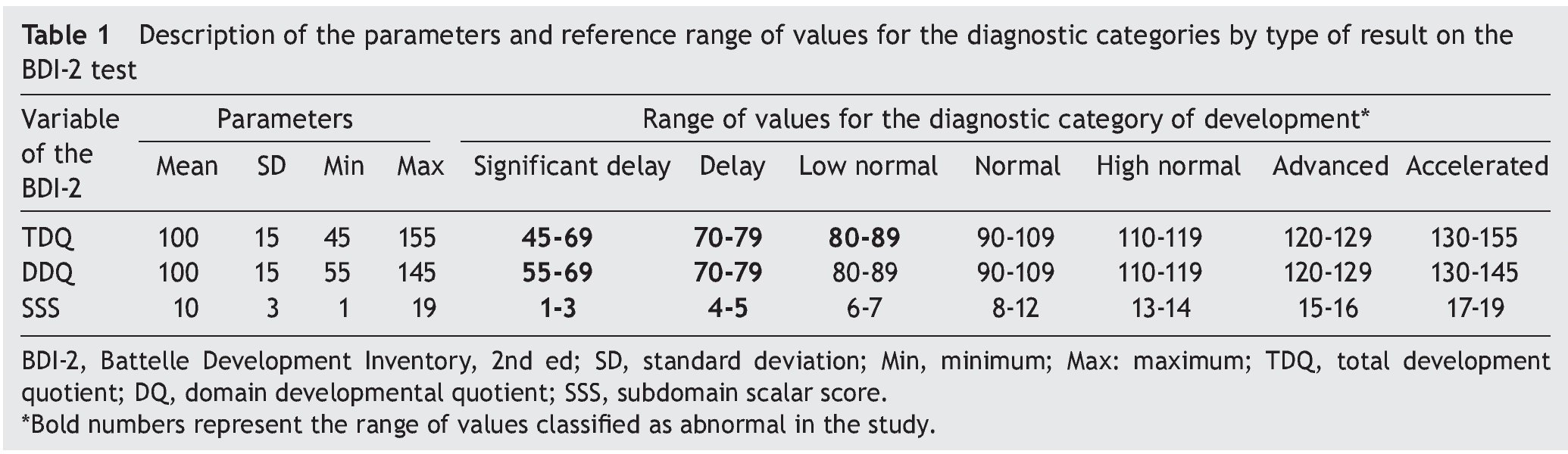

Measurement of development was done according to the three following levels:

a) Total development quotient (TDQ): Weight result of the five domains of the development evaluated in the test. An abnormal result was considered a TDQ <90 (that includes the categories of low normal, delay and significant delay) to identify the greater portion of children with delay in a particular domain6.

b) Developmental quotient of each domain (DDQ): Product of the results in the corresponding subdomains. A DDQ <80 was considered to be a delay.

c) Subdomain scalar score (SSS): Measure of the skill levels and competencies in each specific area. SSS ≤5 was considered to be a delay.

The parameters for each of these variables as well as the categories in which they are grouped are those specified for the BDI-2 test11 and are summarized in Table 1.

2.2.3. Standardization of the evaluation

Application of the modified version of the CDE5 screening test was carried out in the primary care units by 24 psychologists who, in the course of training19,20, obtained a result >95% in the final evaluation and in the supervision of the application in the field a concordance in the shadow study of 100% with monitoring21.

Application of the diagnostic test (BDI-2) was standardized with four psychologists who obtained a score >95% in the final theoretical evaluation of the course and in the shadow study, correctly administered 100% of the reactions for each11. Each booklet was reviewed to corroborate the application and raw scores. The scoring was done using the electronic platform of the test, and the values were captured in a specifically designed spreadsheet.

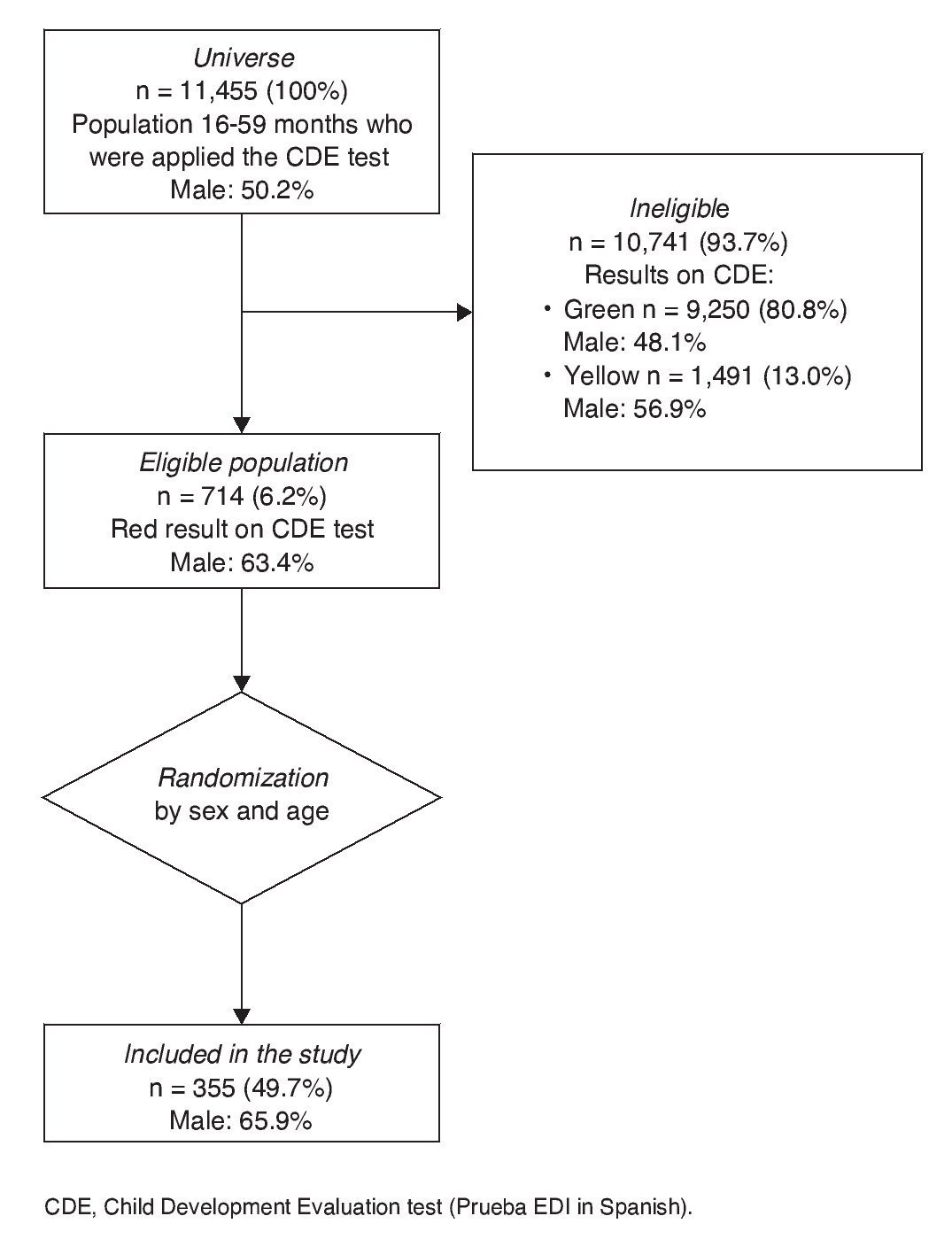

2.2.4. Sample selection

The study was comprised of 11,455 children from 16-59 months of age who were administered the CDE test. Based on the test results, there were 93.7% who were ineligible (n=10,741) due to obtaining normal developmental results (green) or developmental lag (yellow). A population of 6.2% (n=714) was considered to be eligible and who had results for risk of delay (red) (Figure 1). All children identified with risk of delay were referred to health or educational services in order to receive the necessary care as well as to provide counseling to the parents or primary caregivers (normal model of care). For study inclusion a stratified randomization was done by blocks of gender and age group (years). When a patient was identified with risk of delay, the psychologist notified the State coordinator for the project who generated randomized sequences and informed the evaluator by telephone as to which group the child fit. Verbal consent from the parents or caregivers was requested from the study population for the additional application of the diagnostic evaluation test from the level of development using the BDI-211 in a time frame not greater than 2 weeks after application of the screening test. Each test was captured in an electronic platform, reviewed in the State coordination and validated by the research group, corroborating the correct test score and the correct completion of the database as well as the report of the recommendations. Each family member was given a report with personalized advice and recommendations for each child based on his/her developmental profile. The study was approved by the Research, Ethics and Biosafety Commission. The activities were part of those carried out in the HIM/2012/063 study.

Figure 1 Flow of patients included in the study.

2.2.5. Statistical analysis

For the continuous numerical variables (TDQ, DDQ and SSS), Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was given to evaluate the adjustment with the normal distribution. Given that a skewed distribution was found, they were described using medians and interquartile ranges (IQR), and its dispersion was demonstrated using a box diagram. Age was grouped in categories and in a manner similar for the dichotomous or categorical variables, absolute (n) and relative frequency (%) were used. To evaluate differences between dichotomous or categorical variables, x2 test was used and the 95% confidence interval (95% CI) was calculated. Statistical analysis was done using the IBM package SPSS v.20.0; two-tailed p <0.05 was considered statistically significant. A retrospective calculation of the probability of rejecting the null hypothesis that the percentages of delay were similar among gender, nutritional status and type of location (power) was done using the program PS Power and Sample Calculations v.3.0.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the study population

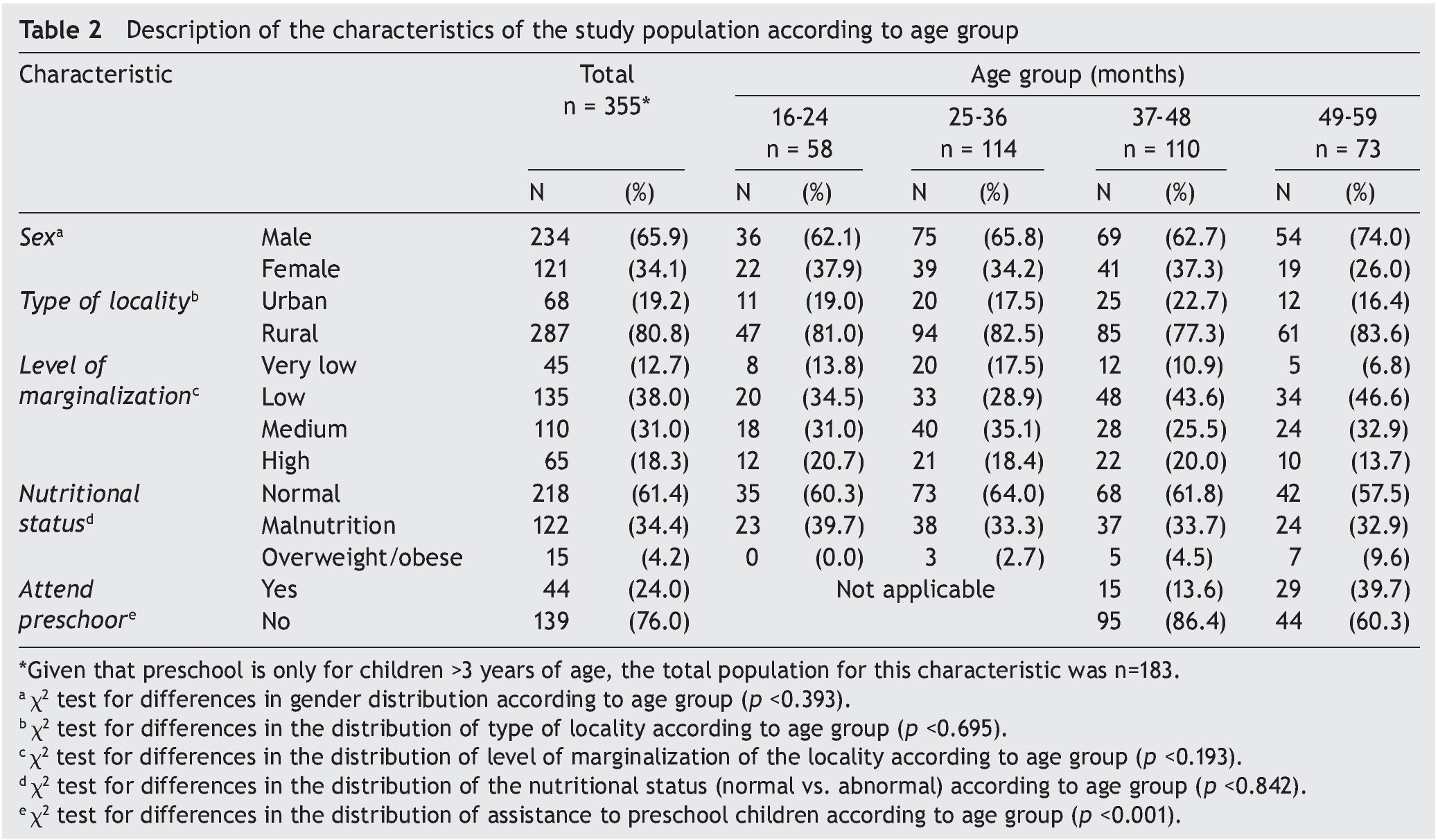

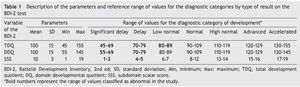

Included in the study were 355 children from 16–59 months of age identified to have risk of delay (“traffic light” in red) on the CDE test (Table 2). Distribution by gender in the total population administered the CDE test (n = 11,455) was 50.2% males and 49.8% females. For the eligible population who obtained a red result on the CDE testing (n = 714), 63.4% were males. Significant differences were found between gender and the global result of the test (p <0.001). Of the study population, 65.9% were males (n = 234) and 34.1%, females (n = 121). No differences were found in the eligible population according to gender (p = 0.173) or age (p = 0.860) among the population included and not included, which translates as appropriate randomization. Distribution of the included population according to type of location was 19.2% for urban (n=68) and 80.8% for rural (n = 287). According to level of marginalization the distribution was as follows: very low 12.7% (n = 45); low 38.0% (n = 135); medium, 31.0% (n = 110); and high, 18.3% (n = 65). These differences were found by the predominance of children evaluated with the CDE test in rural localities. The nutritional status of the participants was normal in 61.4% (n = 218); mild malnutrition in 23.4% (n = 83); moderate malnutrition in 8.7% (n = 31); severe malnutrition in 2.3% (n = 8); overweight in 3.1% (n=11); and obesity in 1.1% (n = 4). Distribution by age group was as follows: 16-24 months 16.3% (n = 58); 25-36 months 32.1% (n = 114); 37-48 months 31.0% (n = 110); and 49-59 months 20.6% (n = 73). No differences were found with the eligible population (p = 0.860). No differences were found in the distribution by group for age or gender (p = 0.393), type of location (p = 0.695), level of marginalization of the locality (p=0.193) or nutritional status (normal vs. abnormal) (p = 0.842). There was a significant difference found (p ≤0.001) in the distribution by age group of the children who attended kindergarten, which was greater in the group 49-59 months of age (39.7%) compared with the group of 37-48 months of age (13.6%).

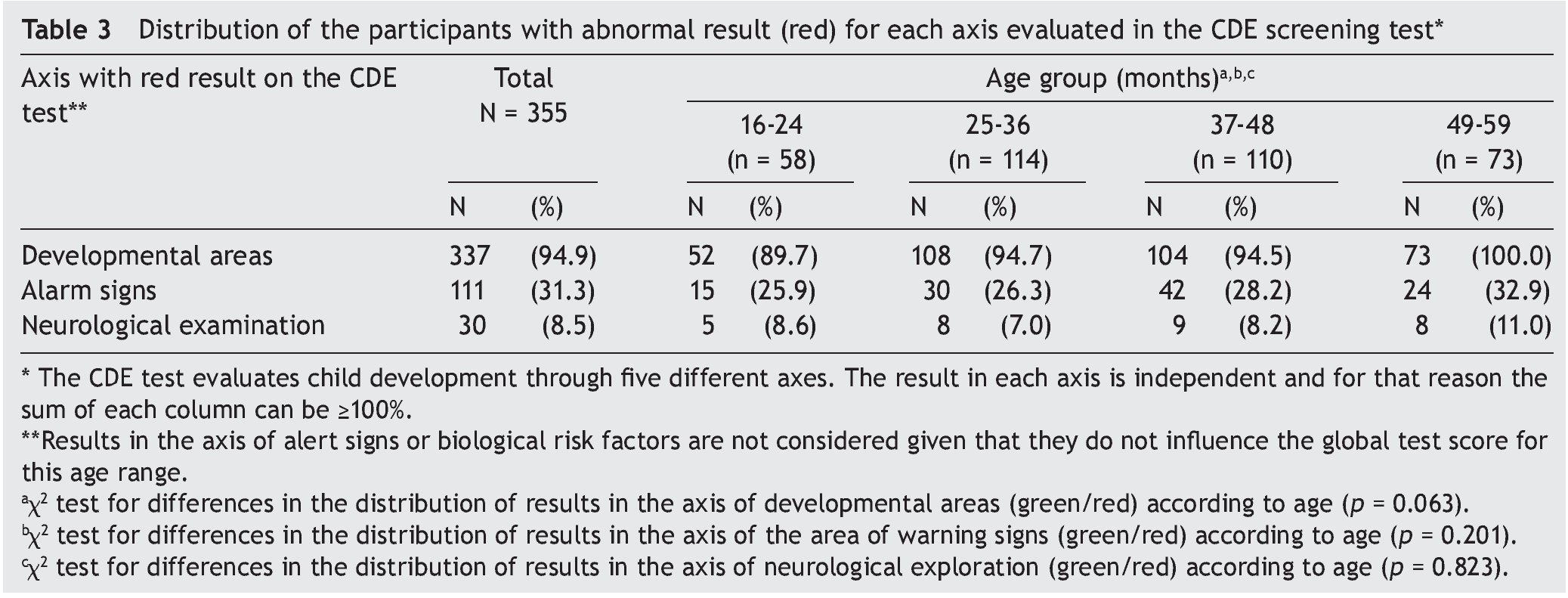

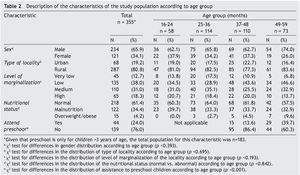

The axis of the CDE test in which the participants obtained a red score, considering that an abnormal result could be obtained in more than one axis were the following: developmental areas 94.9% (n = 337); alarm signs 31.3% (n = 111); neurological examination 8.5% (n=30). There were no differences found in the frequency of alteration for any of the axes according to age group (Table 3).

3.2. Global results in the BDI-2 diagnostic test

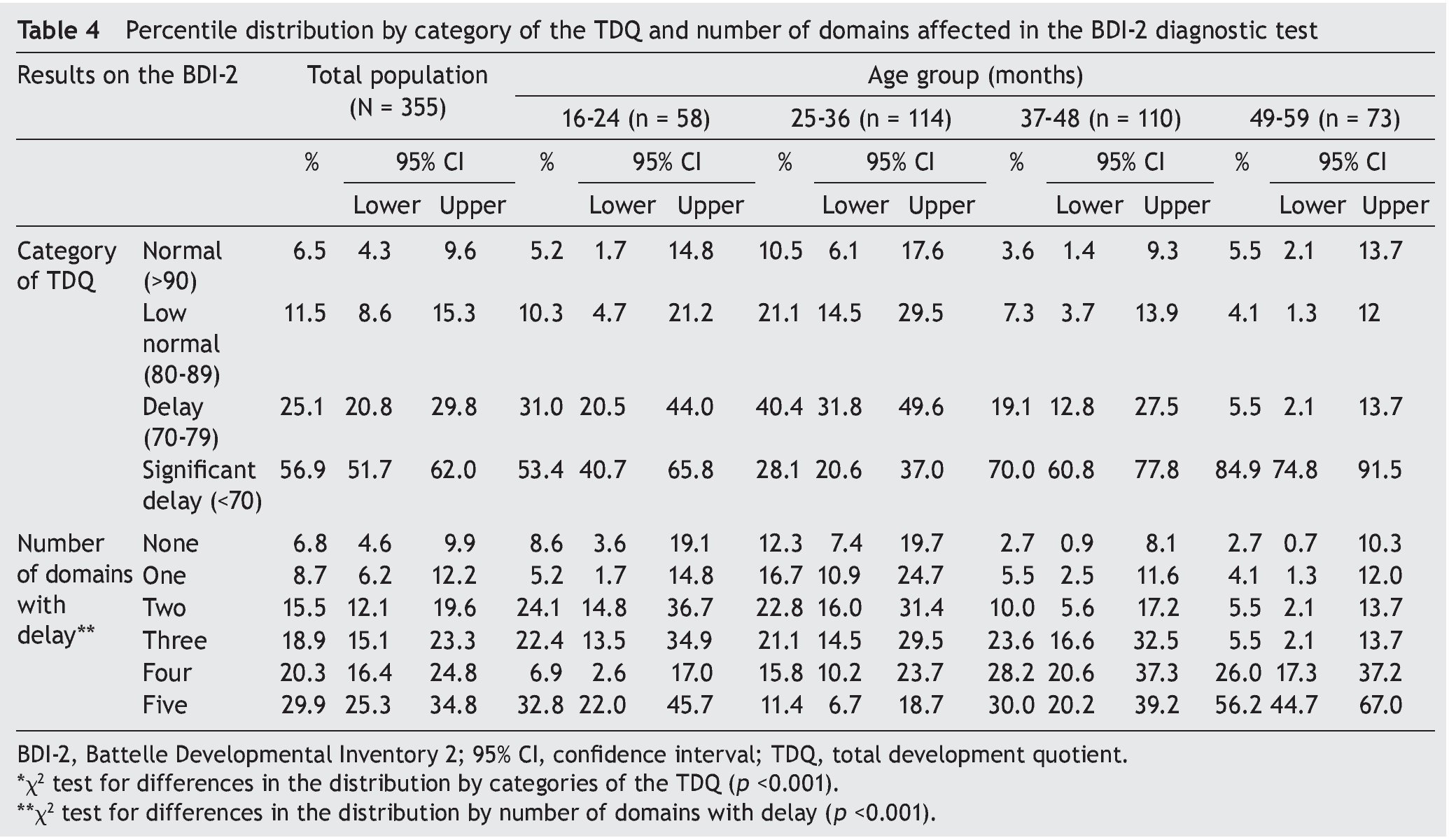

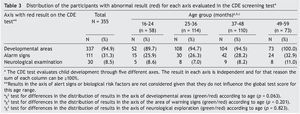

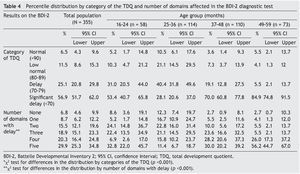

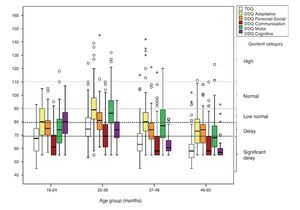

Taking the TDQ as a reference, a diagnosis of an alteration in development in the diagnostic test was confirmed in 93.5% of the total participants: low normal in 11.5%; delay in 25.1%; and significant delay in 56.9% (Table 4). Distribution of the results of the TDQ and DDQ per age group is shown in Figure 2. From the total population, 93.2% (n = 331) had delay in at least one of the five domains (DQ <80) and 69.1% in three or more. There were no significant differences found in the number of domains affected by gender (p = 0.389), nutritional status (p = 0.832) or degree of marginalization (p = 0.117).

Figure 2 Distribution of the total development quotient (TDQ) and the domain developmental quotient (DDQ) by age group of the participants.

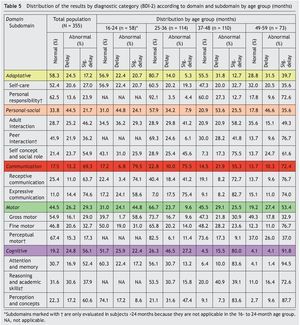

3.3. Results by domain or subdomain in the diagnostic test

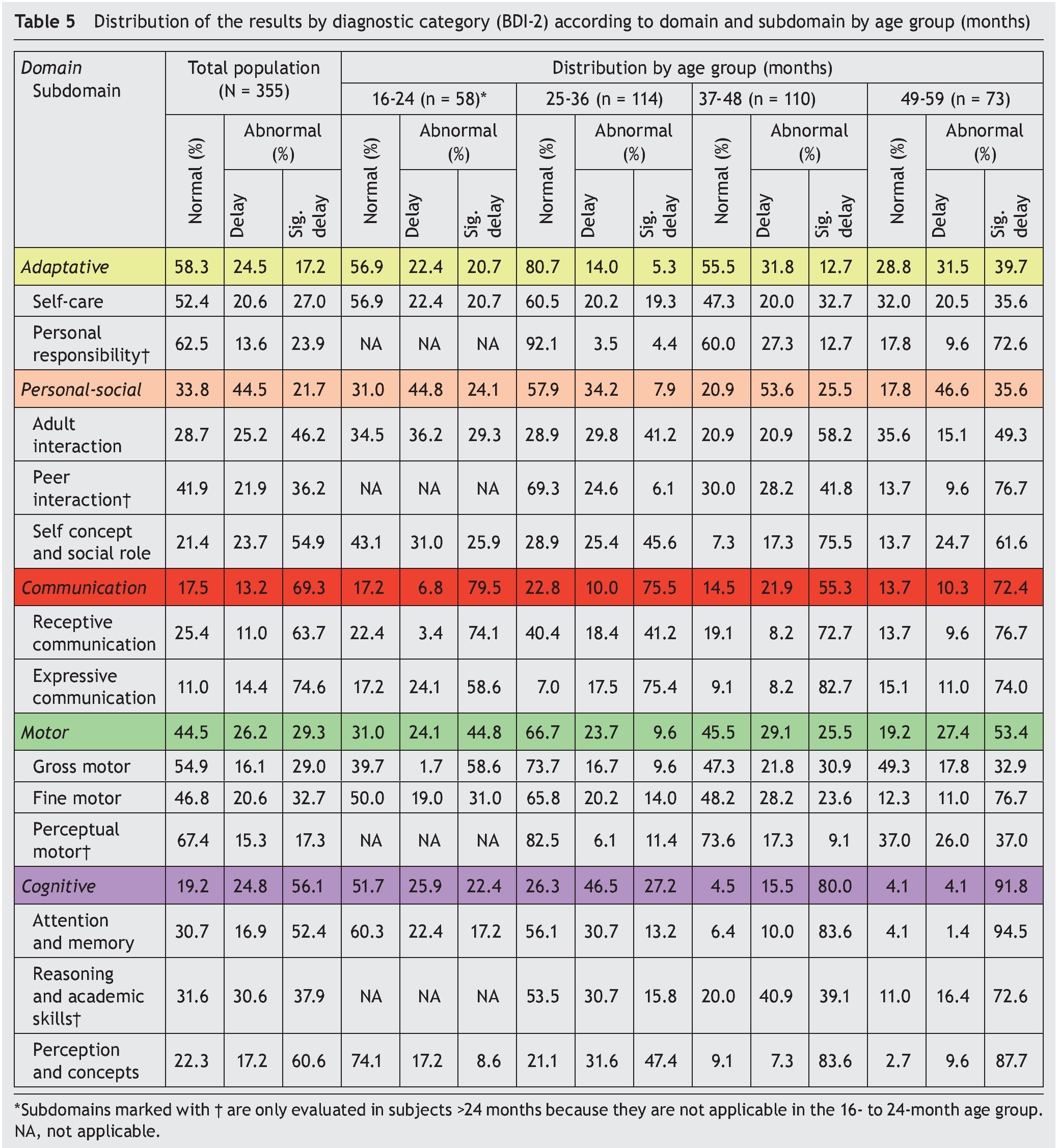

The total percentage of children in whom delay was corroborated (DDQ <80) was different for each of the domains: communication (82.5%); cognitive (80.9%); personal-social (66.2%); motor (55.5%) and adaptive (41.7%). The highest percentage of children with significant delays were found in the domains of communication and cognition (DDQ <70) (69.3 and 56.1%, respectively). When the percentage of participants with delay was compared (DDQ <80 or SSS <6) significant differences were found by gender (female vs. male) in the motor domain (62.8 vs. 51.7%; p = 0.046) associated with differences in motor perceptual subdomain (40.6 vs. 28.5%; p = 0.034). According to type of location (rural vs. urban) differences were found in the communication domain (84.7 vs. 73.5%; p = 0.030) associated with differences in the receptive communication subdomain (77.0 vs. 64.7%; p = 0.036). Differences were also found in the fine motor subdomain (56.1 vs. 41.2%; p = 0.027).

Nine subdomains were fpund to have delay (SSS <6) in >50% of the study population: expressive communication (89.0%); self-concept and social role (78.6%); perception and concepts (77.8%); receptive communication (74.7%); interaction with adults (71.4%); attention and memory (69.3%); reasoning and academic abilities (68.5%); interaction with peers (58.1%); and fine motor skills (53.3%). Table 5 describes the percentages of delay for each domain and subdomain by age group.

4. Discussion

All previously reported information about the CDE test in its modified version6-8 was generated from the results of a controlled sample of participants included in the validation study. This is the first population-based study that analyzes children identified with risk of delay in the CDE test (modified version) administered in primary care facilities to establish diagnostic confirmation of developmental delay and the domains most affected, using the BDI-2 as a reference standard.

The existence of multiple definitions and concepts of developmental delay, the alterations that it encompasses and the tests used make it difficult to define its prevalence22-24.

There was no information found in Mexico about the prevalence of the diagnosis of developmental delay. In spite of this, the percentage of children identified with risk of delay in this study is similar to that reported in other studies where the CDE test was applied based on a population for this age group (16–59 months)25.

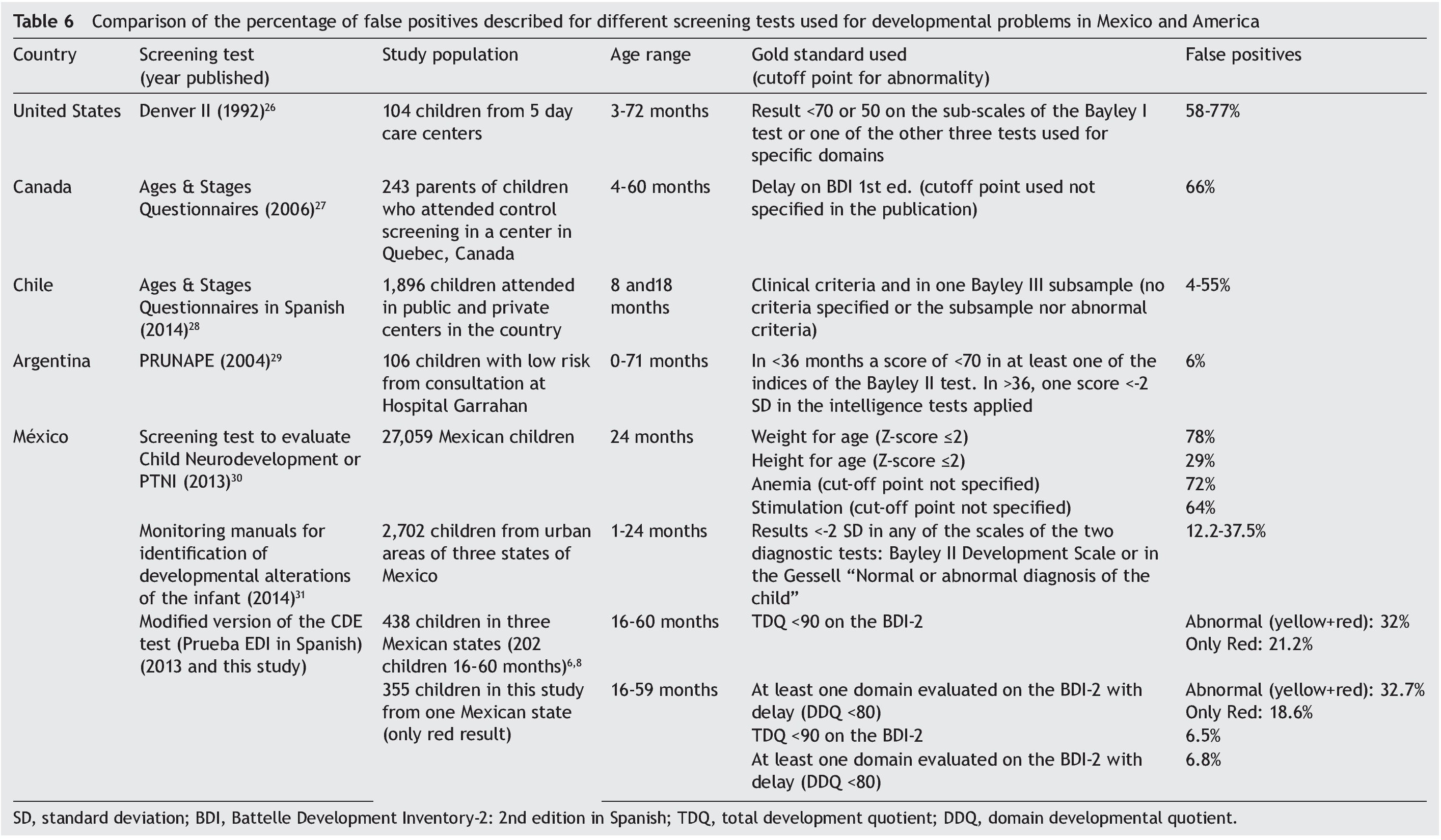

For validation of the CDE test, a TDQ <90 was established as a cut off point for the diagnostic test including the category of low normal, unlike most of the tests that use as a cut-off point a TDQ <70 or <2 SD (Table 6). This decision was taken based on the observation that only 2% of the total of children with low normal TDQ (80-89) had all the domains with DDQ >85, and 34.1% had at least one domain with significant delay6.

A similar proportion of false positives was found in the study, based on a TDQ >90 as well as not having any domain with a DDQ <80. This proportion is less than the percentage of false positives of the total children identified with risk of delay in the validation study8. This difference may be explained by the fact that the modified version was constructed post hoc from what was obtained from two modalities of application of the original test in a population with specific criteria and its properties were estimated from the information generated6, whereas the results of this study were the product of a field application of the CDE test (modified version) in a population base which could be considered as the proportion of false positives for this result.

When these results are compared with what is reported for some screening tests commonly used in Mexico and other countries in America,26-31 the percentage of false positives found in this study was the lowest and of similar magnitude to what was reported for the National Test of Research or PRUNAPE,29 developed and validated in Argentina (Table 6).

When the age groups were compared, there were significant differences found (p <0.001). In the group 16-24 months of age, 74.1% presented significant delay in receptive communication and 58.6% in both expressive communication as well as gross motor skills, with these being the subdomains most affected. The highest percentage of false positives was found in the 25- to 36-month age group both in the total result as well as considering the number of domains with delay. When each subdomain is considered separately, it was observed that for expressive communication 92.9% had an abnormal result and 75.4% significant delay. In this manner, although the TDQ and all DDQ are found in the normal range (10.5 and 12.3%, respectively), only 7% of the children evaluated were true false positives and the remainder presented delay in at least one subdomain which, if not addressed in a timely manner, could cause a more severe delay and an increase in the number of domains involved as observed in participants >37 months of age.

In the age range of 37–59 months >70% of the participants had a TDQ in the range of significant delay. The highest number of participants with three or more domains with delay were found (>80%). The domains most affected were cognitive, communication and personal-social. A higher proportion of children who attend kindergarten was found in the group of 49–59 months compared with the group of 37– 48 months, similar to what is reported in the level of development of these children37. It is essential to conduct a corroboration study of children with normal results (green) or delay (yellow) in the CDE test to evaluate the reliability of the possible results in a population-based study1. The proportion of children who attend preschool (24.0%) is considerably less than the net rate of pre-school coverage reported for the state of Puebla in the 2011-2012 cycle (73.6% of the total number of children 3-5 years)32. This could be one of the factors associated with developmental delay in this age group33.

Of the study participants, 61.4% had a normal nutritional status. There were no significant differences found (p = 0.436; post hoc power calculation for the normal vs. abnormal nutritional status of 0.409) in the percentage of children in whom delay was corroborated by the diagnostic test among the nutritional status categories. A higher proportion of males has been reported in those children identified with risk of delay (65.9 vs. 50.2% in the total of children who had a screening test administered) in other studies in which an association has been found between male gender and delay34-36. Differences associated with a higher proportion of delay in females were only found in the motor domain and in the motor perceptual subdomain. Statistical power calculated post hoc for the proportion of delay according to gender in the rest of the domains as for all the comparisons by type of location was <0.30.

In 93.2% of the children from 16–59 months of age included in the study and identified with risk of delay with the CDE test, the presence of delay in at least one domain evaluated was corroborated by the diagnostic test, although differences in the percentages of delay were observed, both for age as well as for the domain/subdomain evaluated. This evidence supports the recommendation by an expert panel on the application of the BDI-2 test to all children of this age group with a red result on the CDE test in order to establish an individualized plan for management and counseling9,25 as well as functioning as a baseline for monitoring and evaluation of the actions performed to improve the level of development of these children37. It is fundamental to carry out diagnostic corroboration studies in children with normal results (green) or with delay (yellow) on the CDE test in order to evaluate the reliability of the possible results of the field test.

Ethical disclosure

Protection of human and animal subjects. The authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the relevant clinical research ethics committee and with those of the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki).

Confidentiality of data. The authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consent. The authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Funding

This study was carried out with funding provided by the Convenio CPSS/ART.1°/023/2013, carried out between Hospital Infantil de México Federico Gómez (HIMFG) and the Comisión Nacional de Protección Social en Salud (CNPSS).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

To the health teams of the units of primary care and psychologists from the Estrategia de Desarrollo Infantil of the state of Puebla; Miguel Hernández Valle, Miriam Ibáñez Oran, Lizbeth Gabriela Salado Meléndez, Evelyne Rodríguez Ortega, Jessica Guadarrama Orozco, Elías Hernández Ramírez, Ana Alicia Jiménez Burgos, Marta Lia Pirola, Rocío del Carmen Córdoba García, Rodrigo Orcajo Castelán and Socorro De la Torre García.

Received 26 October 2015;

accepted 2 November 2015

* Corresponding author.

E-mail:antoniorizzoli@gmail.com (A. Rizzoli-Córdoba).