1. Introduction

In Mexico, public health policies aimed at children are focused on meeting health needs and promoting equity. The entire population has access to universal, free public health services, independent of the affiliation with any health insurance program.

During the past 12 years, public health programs have significantly expanded their coverage in terms of health promotion, prevention and disease control. For persons without social security affiliation, preventive care is covered by the Guaranteed Basic Health Package that beneficiaries of Prospera Program receive through the health sector.1 It is also guaranteed in the Universal Catalogue of Health Services (Catálogo Universal de Servicios de Salud, CAUSES) and is part of the focus of the IMSS–PROSPERA program. Some of the actions include the following:

i) Strengthening decentralization of public health actions to State Health Services.

ii) Expansion of public health programs. For example, between 2006 and 2013, the vaccination schedule for children <5 years old expanded from 6-13 biological strains and new vaccines were introduced for other age groups such as the vaccine for human papilloma virus for girls between 9 and 12 years old.

iii) Modernization of epidemiological surveillance.

iv) Strengthening of intersectoral actions to address specific problems such as anti-tobacco law and the Mexican Initiative for the Prevention of Traffic Accidents.

Increased investment in vaccine production through the state-owned company Laboratorios de Biológicos y Reactivos de México, S.A. de C.V. (BIRMEX), which produces vaccines against polio, tetanus and diphtheria and produces anti-scorpion and snakebite serums.

In the case of the population affiliated with Social Security, PREVENIMSS Program has made substantial progress in coverage and has expanded the supply of public health services, whose contents follow the guidelines established by the Ministry of Health.2

From a programming standpoint, public health actions aimed at children include universal vaccination, prevention and control of diarrheal diseases and acute respiratory infections, and nutrition control by monitoring the growth and development of children <5 years of age.3 From the operational point of view, these actions are implemented through the provision of individual attention during well-child visits, the Permanent Vaccination Program and the three National Health Weeks.4

Public health services are in a stage of transition: from a model aimed at achieving survival (e.g., reducing neonatal mortality) to care models that help children reach their full potential. Reduction in mortality is relevant, but insufficient to ensure optimal health conditions. Consequences of suboptimal health are serious in the medium and long term.

In Mexico, the heterogeneity of the health conditions of children will remain for a long time from both perspectives. It will be essential to continue implementing actions of the survival model; however, conditions already exist for deploying new actions of the fully developed model. This is fully justified because, on the one hand, the country did not achieve the Millennium Development Goals in terms of reducing by two thirds the rates of infant and child mortality, which is required to improve the access and quality of perinatal services. On the other hand, several efforts at the national level are underway to assess the degree of neurological development of children5 and to implement interventions focused on early childhood development.6 Early childhood development is a challenge in terms of scope, scale and impact; failure to provide optimal environments for children results in reduced income and gross domestic product along with higher rates of illness, depression and crime.7

The National Center for Health of Children and Adolescents (CeNSIA) promotes that well-child visits have a perspective of comprehensive care in which services of health promotion, prevention and detection are granted to children <1 year of age and children <5 years of age in the areas of nutrition, child development, vaccinations, accident prevention, acute diarrheal diseases and acute respiratory infections, along with detection of Turner syndrome.8

The current model of provision of public health services faces major challenges in implementing these actions holistically. Demographic and epidemiological changes occurring in the population are dynamic and organizational and process constraints in the provision of primary care services prevent a correspondence between the supply of services and needs that should be addressed.9 It is still possible to identify that the programs are isolated and often compete for resources and that preventive services personnel who provides these services must multiply themselves to achieve the expected goals. This situation motivates proposing that, operationally, processes can be aligned and efficient formulas can be found to provide the maximum possible amount of services at every contact with the user whose visit to a health facility may be for preventive or curative care. This vision must change to a perspective in which each child’s contact with health services provides the opportunity to receive preventive actions and health promotion.

Additionally, the staff responsible for public health activities requires ongoing training, not only in processes and procedures but also in areas that allow a better understanding of their work, e.g., knowing the influence of the determinants of health during childhood or being familiar with the area of early childhood development. Knowledge of the influence of family, cultural, environmental and economic aspects of children’s health status allows a better perspective for the provision of public health services.

In this paper, a framework is proposed to support the implementation of an integrated care model of public health services directed to children <5 years of age whose attributes are consistent with the health needs of this age group and the policies and public health programs aimed at children.

2. Conceptual framework for integrated care

The term “integrated care” refers to the description of teams of health providers who work together to provide health services. There are different ways of providing health services through teams: parallel, consultative, collaborative, coordinated, multidisciplinary, interdisciplinary and integrative.10 The provision of services reflects a continuum of care, ranging from the independent interaction of a provider with a user–in which the provider performs his/her work determined in accordance with the scope of his/her practice, independently from other suppliers that even work at the same health facility (parallel provision)–until inclusive provision, which consists of a combination of conventional and complementary medicine and provides individual-centered care and is based on decision making and ongoing support. This is provided by an interdisciplinary team whose work is guided by consensus, respect and shared vision of health care required by the individual.11

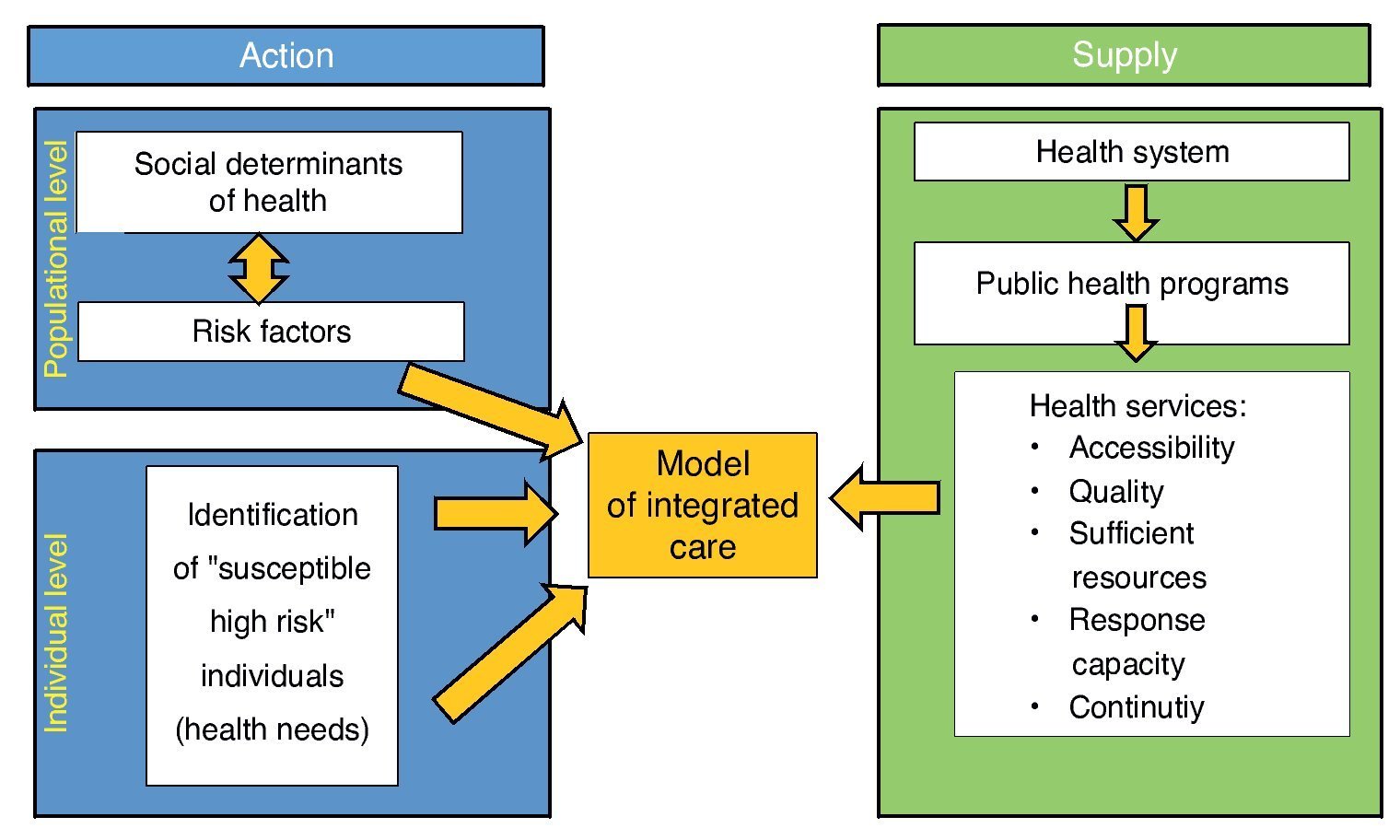

From the supply point of view, it is considered as the existence of a system that has public health programs focused on meeting the needs of the population and are provided through user-centered12 health services and whose attributes should be accessibility, quality, availability of resources (human, technical, financial), responsiveness and continuity of care.

Public health actions in childhood have short-, medium-and long-term effects. Public health in childhood is focused on promoting and protecting the health and welfare as well as the prevention of diseases in infants, children and adolescents using the skills and organized efforts of health personnel, public and private institutions, and society. To achieve its mission, actions are based on knowledge of the patterns of health and disease, identification of the factors that affect their health and how these can be modified to improve health and well-being in this age group.13

Human development, health and welfare are linked with socioeconomic and educational level. The roots of learning, education and adaptive behaviors that support physical and mental health are formed during the first years of life and exert long-term influences on health during adulthood and social and community function. The Institute of Medicine of the U.S. defines health of children as the extent to which, individually or in groups, children are capable or qualified to accomplish the following: a) develop and achieve their potential, b) meet their needs, and c) develop capabilities to successfully interact with their biological, physical and social environments.14

On the demand side, integrated care has an individual and population perspective. From the individual point of view, it identifies those who are susceptible and are at “high risk” and offers/provides some protection. Intervention addressed to individuals is subject to motivation for the participation of both the individual and the health care provider. The risk/benefit ratio is favorable; however, costs can be high, it is palliative and temporary and its potential is limited.15 To complement this, the perspective of the population tries to control the causes of the incidence of specific problems and seeks to mitigate risk factors, e.g., modifying their lifestyle to reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease. The disadvantage is that population benefits are achieved, but individuals cannot perceive them (vaccines, use of automobile seat belts, lifestyle changes, etc.). Not all individuals receive an individual benefit because not everyone will develop a health problem. Successful prevention is the unwanted event not occurring; therefore, users do not perceive it.

The comprehensive care model also considers the knowledge and understanding of the influence of the determinants of health (family, social, environmental and cultural) of the child. Increase in life expectancy at birth and decreased neonatal mortality and infectious diseases, as well as the increase in chronic conditions, will also accompany the understanding of the magnitude of environmental, social and economic factors on the health of children, which influence positively or negatively. This poses a major challenge to propose a comprehensive public health model whose actions should have an intersectoral and interdisciplinary character (Fig. 1).

Figure 1 Conceptual framework of integrated care.

3. Functional model of integrated care

A model of care is a multifaceted concept that broadly defines the best practice in the provision of services to users, considering its career in the different states of a condition, injury or event. Therefore, the model of care must have attributes such as ensuring that users receive appropriate care in a timely manner, provided by the proper health team and in the right location.16

The health system must be flexible to incorporate different models of care in terms of cultural and social characteristics of users and, consistently, have structural features, resources and personnel so that services are able to meet health needs in a comprehensive and culturally acceptable manner.

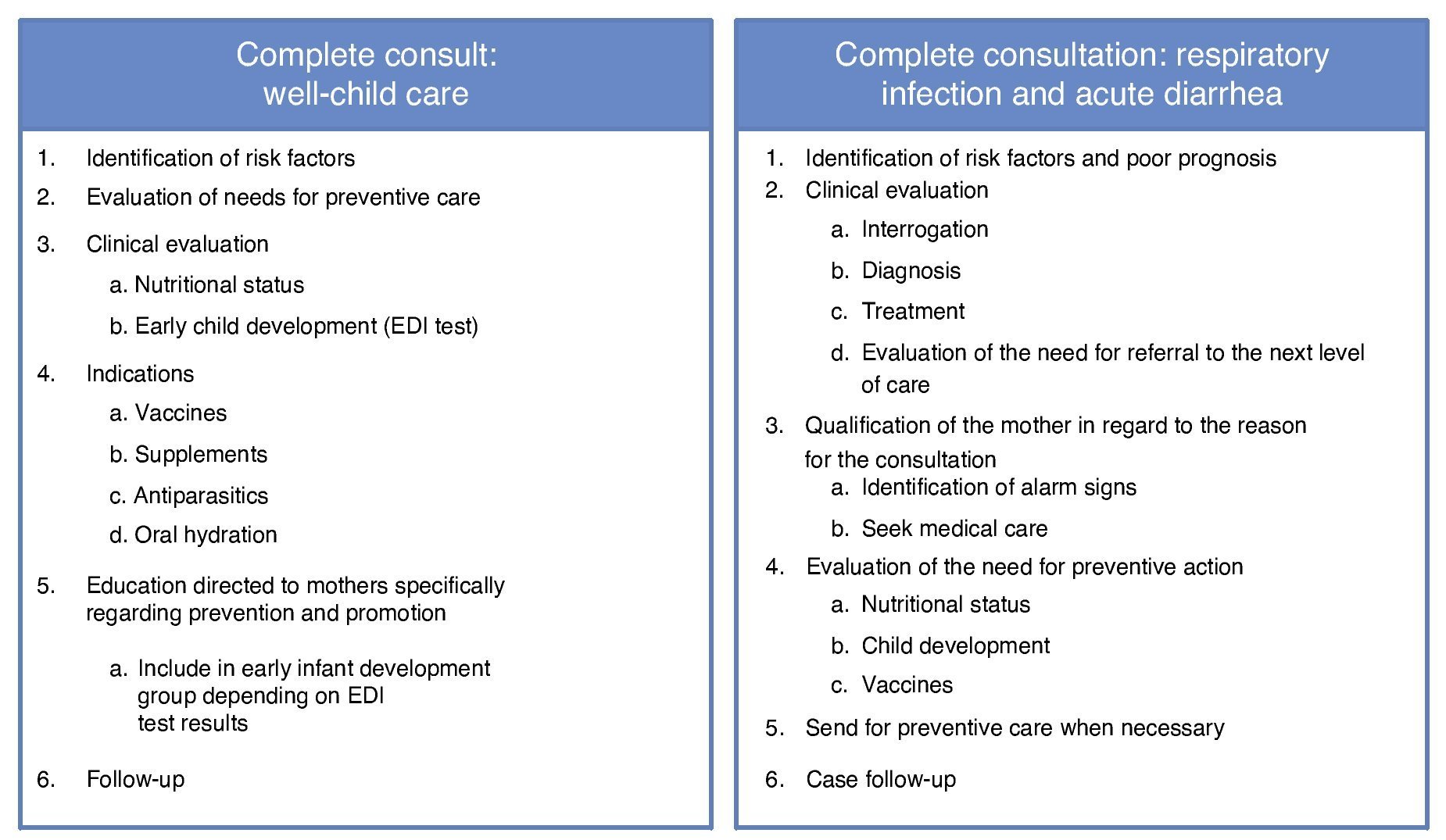

The proposed operational model is twofold. Comprehensive consultation should be provided during well-child care and in cases of acute respiratory infection and diarrhea. The importance of comprehensiveness is justified in different studies. Evaluations have reported persistent problems such as malnutrition and anemia.17 Vaccination coverage has not achieved the expected goals despite the fact that vaccinations increased from 6-15 immunogens in a short time, and the proportion of preschool children with overweight/ obesity is increasing. There are also assessments that indicate structural and organizational services that limit the effectiveness of action problems, which justifies reconsideration of the current model of providing public health services.

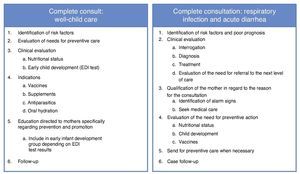

Figure 2 schematically proposes activities to be developed for well-child care and care of patients with diarrhea and acute respiratory infection. Regarding well-child care, it includes the identification of risk factors, assessment of preventive care needs (depending on national programs), clinical assessment focused on nutritional status and child development (using the Early Development Inventory, EDI),5 specific indications such as vaccinations, prescriptions for supplements, deworming and oral rehydration salts, mother’s education on prevention and health promotion including the invitation to join the group of early childhood development (depending on the results of the EDI), and follow-up actions.

Figure 2 Operative model of integrated care at <5 years of age.

The full consultation in cases of respiratory infection and acute diarrhea aims to provide the highest quality of care possible using current guidelines for clinical practice in Mexico18-20 through specific actions such as identifying risk factors and poor prognosis, clinical assessment, maternal education regarding the reason for consultation, emphasizing prompt health care-seeking behavior in case of complications, assessing the need for preventive action, and follow-up of cases.

An integrated services model is complex because the structure (personnel, organization, input) should facilitate teamwork for the provision of services. Processes must facilitate coordination and communication among the different members of the health team and between this communication and users. In public health there are multiple providers involved in the care processes; therefore, it is essential to achieve decisions based on consensus and to promote team-work, which must be able to recognize the individual user needs.

The expected results can also achieve greater measurement range. In terms of public health it is expected that actions help individuals and the population in order to achieve the best level of health possible (effectiveness or impact), understood as welfare beyond the conception of physical and mental function and which also includes the perception of users. The provision of integrated public health services based on teamwork is a challenge to overcome as public health services are currently provided through vertical programs. This creates a scenario in which health providers focus on care in terms of the multitude of programs and compliance goals and may forget that the child sitting in front of them is an individual for whom it is important to receive comprehensive care.

It is essential to modify the structure and processes of care to truly achieve the provision of comprehensive services as well as to implement actions to measure the quality, efficiency and effectiveness of services. Measuring productivity and coverage does not provide sufficient information to identify the impact, quality, efficiency and equity that public health services currently achieve.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest of any nature.

Received 16 January 2015; accepted 16 January 2015

☆ Please cite this article as: Pérez Cuevas R, Nakamura López MÁ, Pascasio Martínez ZL, Mancilla Gallegos NV, Montesinos Álvarez ME, Rodríguez Ramos SL, et al. Propuesta conceptual de un modelo operativo de atención integrada de servicios de salud pública para la niñez. Bol Med Hosp Infant Mex. 2014;71:377-386

* Corresponding author.

E-mail: rperez@iadb.org (R. Pérez Cuevas).