Introducción: La infección del tracto urinario en los niños es reconocida como una causa de morbilidad y de condiciones médicas crónicas, por lo que resulta indispensable conocer con claridad la patogénesis de esta enfermedad. Sin embargo, la resistencia creciente complica su tratamiento ya que aumenta la morbilidad, los costos, la estancia hospitalaria y el uso de fármacos de mayor espectro antimicrobiano. El propósito de este estudio fue determinar la susceptibilidad antimicrobiana de los uropatógenos aislados en niños.

Métodos: Se incluyeron en el estudio 457 niños que asistieron a la consulta externa y a urgencias del Hospital Infantil de México Federico Gómez, con síntomas de infección del tracto urinario baja no complicada. La orina fue tomada a la mitad del chorro o por cateterismo, y se realizó la identificación y la susceptibilidad antimicrobiana.

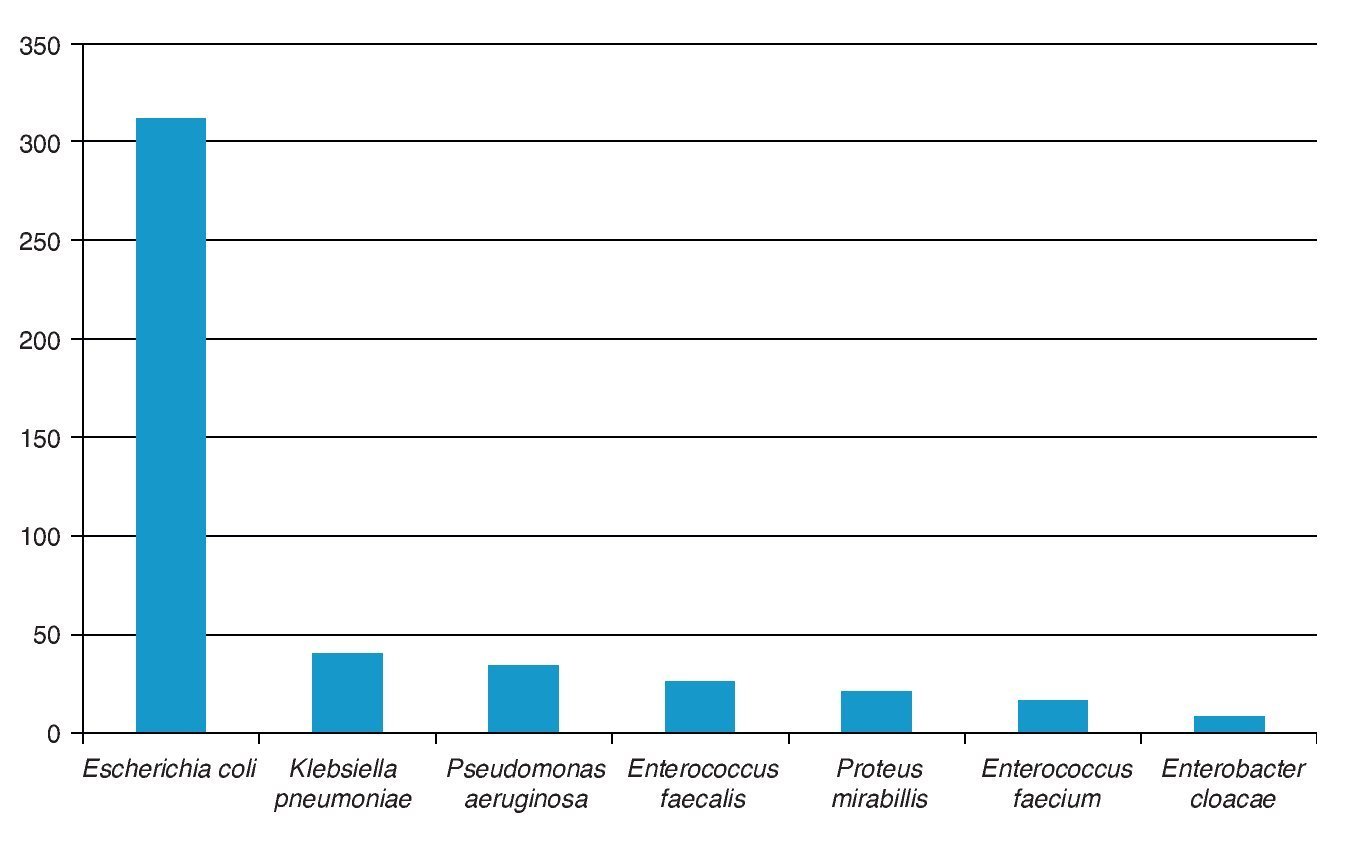

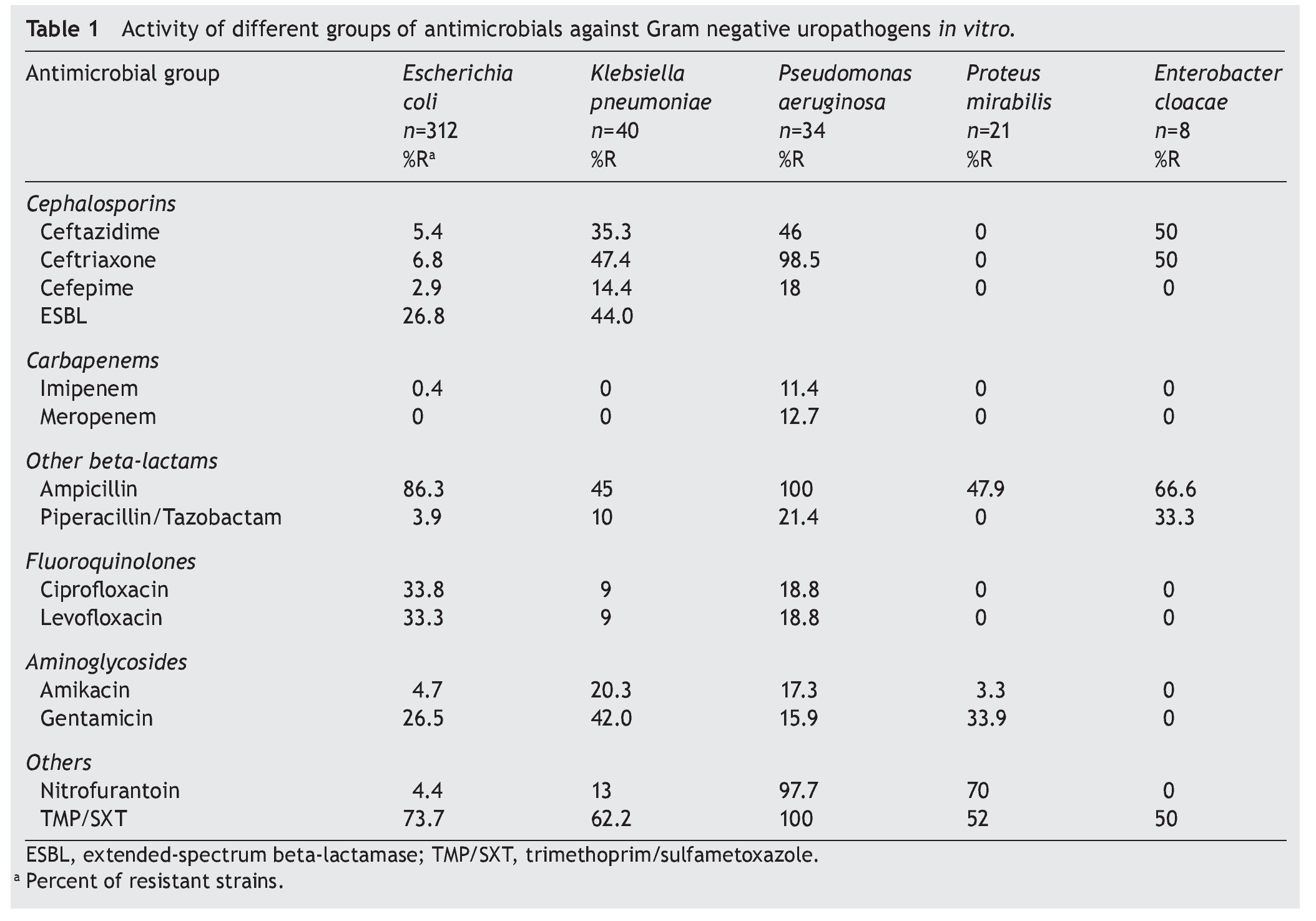

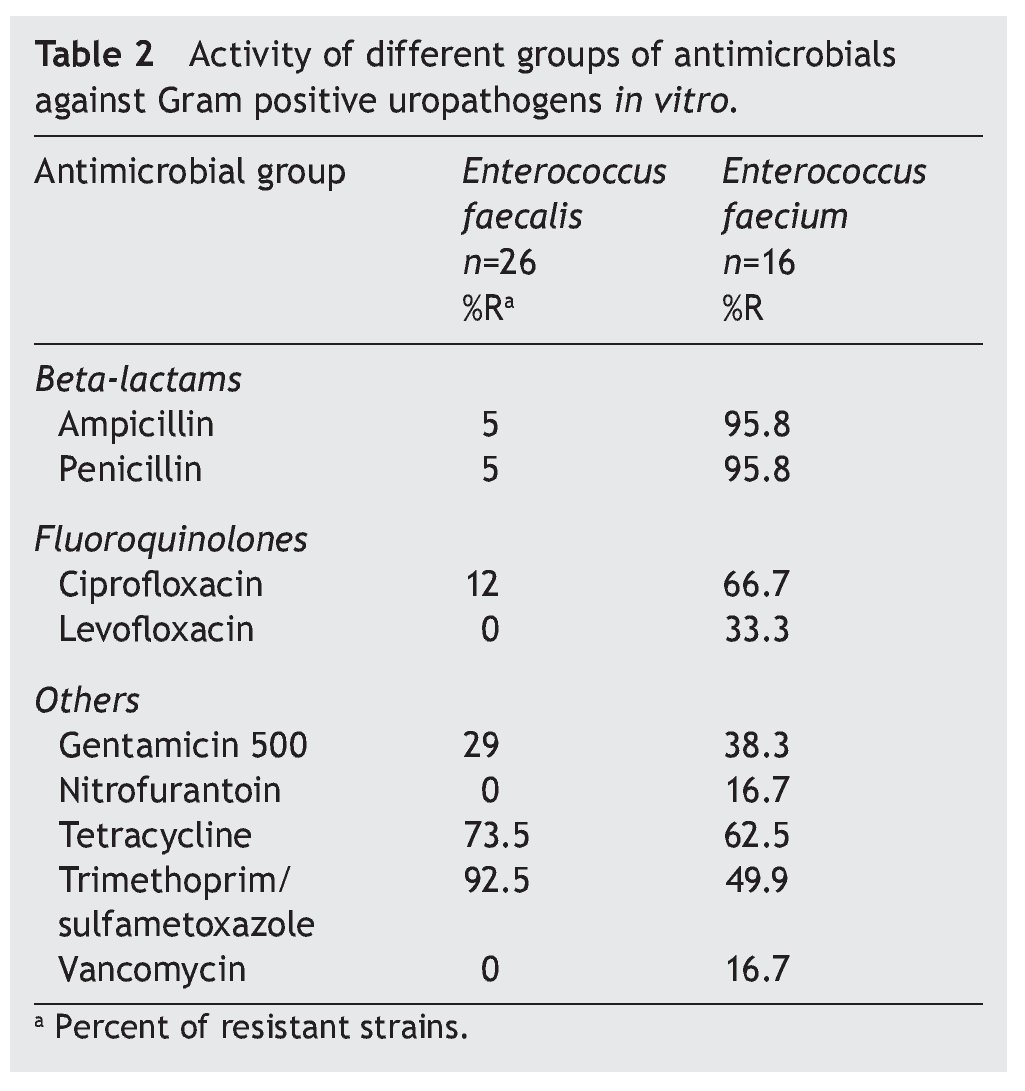

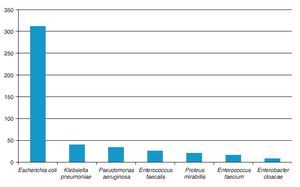

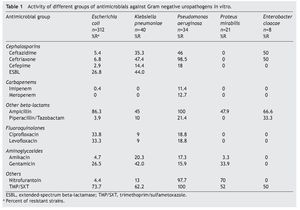

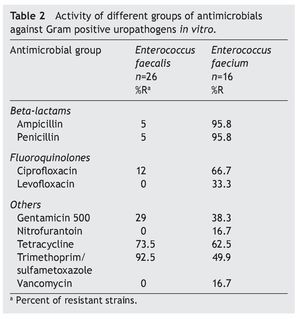

Resultados: Los patógenos aislados con mayor frecuencia fueron: Escherichia coli (E. coli) (312, 68.3%), Enterococcus spp. (42, 11%), Klebsiella pneumoniae (K. pneumoniae) (40, 8.7%), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa) (34, 7.5%), Proteus mirabilis (P. mirabilis) (21, 4.5%), Enterobacter cloacae (8, 1.7%). La resistencia para trimetoprima/sulfametoxazol fue del 73.7, 62.2, 100, 52, 50%,respectivamente, para E. coli, K. pneumoniae, P. aeruginosa, P. mirabilis y Enterobacter spp., del 92.5% para Enterococcus faecalis (E. faecalis) y del 49.9% para Enterococcus faecium (E. faecium). Para ampicilina fue del 86.3, 45, 100, 47.9 y 66.6% para las mismas bacterias, respectivamente. Para ciprofloxacina del 33.8, 9, 18.8, 0 y 0%; para nitrofurantoína del 4.4, 13, 97.7, 70, 0% para enterobacterias, del 0% para E. faecalis y del 16.7% para E. faecium.

Conclusiones: Los antimicrobianos frecuentemente prescritos para el tratamiento empírico de la infección del tracto urinario no complicada demuestran resistencia importante o baja susceptibilidad cuando se les probó frente a las cepas aisladas.

Background: Urinary tract infection in children is well recognized as a cause of acute morbidity and chronic medical conditions. As a result, appropriate use of antimicrobial agents, however, increases antibiotic resistance and complicates its treatment due to increased patient morbidity, costs, rates of hospitalization, and use of broader-spectrum antibiotics. The goal of this study was to determine antibiotic susceptibility to commonly used agents for urinary tract infection against recent urinary isolates.

Methods: A total of 457 consecutive children attending the emergency room at the Hospital Infantil de México Federico Gómez with symptoms of uncomplicated lower urinary tract infection were eligible for inclusion. Patients who had had symptoms for >7 days and those who had had previous episodes of urinary tract infection, received antibiotics or other complicated factors were excluded. Midstream and catheter urine specimens were collected. All isolates were identified and the in vitro activities of antimicrobials were determined.

Results: The most frequently isolated urinary pathogens were as follows: Escherichia coli (E. coli) (312, 68.3%), Enterococcus spp. (42, 11%), Klebsiella pneumoniae (K. pneumoniae) (40, 8.7%), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa) (34, 7.5%), Proteus mirabilis (P. mirabilis) (21, 4.5%), Enterobacter cloacae (8, 1.7%). The resistance to trimetoprim/sulfametoxazol (%) was 73.7, 62.2, 100, 52, and 50, respectively, for E. coli, K. pneumoniae, P. aeruginosa, P. mirabilis and Enterobacter spp., 92.5 for Enterococcus faecalis (E. faecalis) and 49.9 for Enterococcus faecium (E. faecium). Ampicillin was 86.3, 45, 100, 47.9, and 66.6% for the same strains, ciprofloxacin 33.8, 9, 18.8, 0, 0%, nitrofurantoin 4.4, 13, 97.7, 70, 0%; to E. faecalis 0% and 16.7% to E. faecium. Conclusions: Frequently prescribed empirical agents for uncomplicated urinary tract infection demonstrate lowered in vitro susceptibilities when tested against recent clinical isolates.

1. Introduction

The frequency of a urinary tract infection (UTI) may vary according to the age and gender of the patient. Symptomatic infection occurs in 1/1,000 newborns and infants 1 month of age, being most common in males (ratio 2.7:0.7) up to the first year of life. Generally, the risk of a UTI during the first decade of life is 1% for males and 3% for females. However, in the second decade of life it predominates in girls at a ratio of 4:1.1-3

Uncomplicated acute UTI is one of the most common bacterial infections responsible for significant morbidity as well as elevated health care costs. Although it may frequently be self-limiting and easily treated with antibiotics, it frequently does not completely resolve and may cause recurrences despite the use of antibiotics.

Patients with cystitis/urethritis present a lower incidence of urinary tract symptoms: urgency, dysuria and frequency, which are caused by inflammation of the mucosal epithelium where the urinary bacteria adhere. Upper UTI is the consequence of the presence of a pathogen in the kidney or the ureter that has extended from the bladder or the urethra. Patients with pyelonephritis have upper urinary tract symptoms accompanied by other systemic symptoms: high fever, abdominal flank pain, and heaviness in the pelvis, caused by inflammation of the renal parenchyma.3-7

Children with UTI usually present without the signs and symptoms considered classical when they present in adults. Also, depending on age, there are variations: children <3 months old often present with non-specific symptoms that include fever, refusal to feed, nausea with or without vomiting, irritability, lethargy, foul-smelling urine and jaundice. Children 3 months to 2 years of age have more specific symptoms such as turbid, foul-smelling urine, increased frequency of urination, hematuria with nonspecific signs, fever, vomiting, anorexia and difficulty gaining weight. Children between 2 and 5 years of age present with abdominal pain and fever. The majority of children >5 years of age present with dysuria, increased frequency of urination and urgency; ~7-8% of girls and 2% of boys have a UTI during their first 8 years of life.2,3,8-10 One component that supports the diagnosis is present in the urinalysis: presence of positive reactions documenting nitrites and observation of inflammatory cells (leukocytes) and bacteria.3,7

Isolation of the pathogen is essential for definitive diagnosis. Therefore, it is important to consider the following points: 1) urine should be obtained prior to the administration of antibiotics; 2) sample collection for the culture should be obtained midstream with passage of a urethral catheter or by suprapubic puncture; and 3) urethral catheterization, an invasive procedure indicated only in very young children.

A culture with >50,000 CFU of a single bacterial species is accepted as a positive culture. Usually, the culture result is not available until 24 h. For this reason, administration of antibiotics is done empirically. Early treatment is intended to eradicate the pathogen, prevent urosepsis and reduce kidney damage.9-11

E. coli continues to be the most common etiological agent for UTI and initial empirical treatment is directed to its treatment; however, in recent years a gradual resistance has been demonstrated to the usual first line choice of antibiotics prescribed. This situation is also common for other urinary pathogens.11-18

In 2010 in Mexico it was reported through the National Epidemiological Surveillance System that UTIs occupied third place among the principal causes of morbidity.19 These reports have not specified the antimicrobial susceptibility in children.

Therefore, the purpose of this work was to determine the susceptibility to antimicrobial drugs commonly used for the treatment of acute uncomplicated UTI against isolated uropathogens in a childhood population who attended the Emergency Department of the HIMFG from 2008 to 2012.

2. Patients and methods

A card was designed to collect demographic data from each experimental group: age, sex, previous urinary history, history of recent antibiotic treatments, presence of baseline pathology that coincides with the current condition, as well as urine sample with results and interpretation of leukocyte esterase and nitrite, cells and bacteria. The study of the urine sample from children hospitalized in the Emergency Department of the HIMFG was carried out with parents or responsible party being informed of the risks and benefits and voluntarily signed informed consent for the different procedures to be performed.

2.1. Inclusion or elimination criteria

Inclusion criterion was the availability of general information for each patient. Children with baseline urinary pathology and history of repeated UTIs were not accepted as well as those children with drainage catheters. Also not included were children with history of UTIs >7 days of evolution, children with history of recent treatment (7-14 days prior) or current antibiotics. For case definition it was considered that the UTI was community acquired.

2.2. Urine sample collection

A midstream collection was performed in children who were able, age-wise, to cooperate with taking of the sample. In children <2 years of age the sample was obtained by means of a transurethral catheter with prior asepsis of the perineal-genital area. To minimize wipe contamination towards the interior, the initial stream was eliminated.

2.3. Culture interpretation

The presence of a uropathogen is of clinical interest when there is growth of >50,000 CFU of a sole species and, occasionally, two bacteria with similar quantity.14 Only one positive sample was considered in each patient.

2.4. Microbiological identification

Urine samples of pediatric patients with clinical data of UTI were studied. Once the urine sample was obtained, the method of dilution was used (1:100). From this dilution, 100 ml was taken to inoculate a cystine lactose electrolyte-deficient (CLED) agar slide with the assistance of sterile glass angle, spreading the sample uniformly across the surface of the culture media. The slide was kept facing upwards for 5 min so that the inoculum would be absorbed. The slide was rotated and incubated at 35±1 oC for 24-48 h under aerobic conditions. Identification of the colonies was done according to their morphology and identification by the Vitek 2XL system (BioMérieux).

2.5. Antibiotic susceptibility

Antibiotic susceptibility tests were done according to CLSI guidelines20,21 using the Vitek 2XL (BioMérieux) automated system and the Kirby-Bauer method as an alternative to verify resistance of Enteroccocus faecium to vancomycin.

The quality control strains used were as follows: for Escherichia coli, ATCC25922 and 35218; S aureus, ATCC29213; Enterococcusfaecalis, ATCC29212 and 51299; Pseudomonas aeruginosa, ATCC27853; and Klebsiella pneumoniae, ATCC700603.

The strains for K. pneumoniae, E. coli, and Proteus mira-bilis, with minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) >2 mg/ml for ceftazidime and/or ceftriaxone and/or aztreonam, were catalogued as bacteria with resistance for extended spectrum β-lactams (ESBL) (CLSI 2012).20-21

3. Results

There were 457 patients studied; 217 (47.48%) were girls and 240 (52.52%) boys. Age distribution was as follows: 91 <6 months of age (20%); 137 were between 7 and 12 months of age (30%); 114 from 1-5 years (25%); and 115 were >5 years of age (25%). The most commonly isolated pathogen was E. coli (312 patients, 68.3%) and in second place were both E. faecalis and E. faecium (42, 9.7%). These pathogens, together with K. pneumoniae (40, 8.7%), represented 86.2% of all isolates collected (Fig. 1).

Figure 1 Distribution of uropathogens causing uncomplicated urinary tract infection.

The resistance of E. coli to traditional drugs was as follows: trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP/SXT) was >73%; ciprofloxacin 34%; nitrofurantoin 4.4%; amikacin 4.7%; and for gentamicin 26.5%. The susceptibility was variable for third- and fourth-generation cephalosporins. Approximately one of every four strains resistant to E. coli showed an ESBL pattern. In K. pneumoniae, half of the strains (44%) had this pattern of resistance. In 26/312 strains of E. coli (8.3%), multiple resistance phenotypes were found (ampicillin-ciprofloxacin and TMP/SMT). Resistance of K. pneumoniae to the same drugs used for conventional treatment was >62% for TMP/SXT and 1/10 to ciprofloxacin. Resistance to cephalosporins was present in 14% (cefepime) and 47% (ceftriaxone). There was no resistance shown to imipenem or to meropenem. The resistance of P. aeruginosa to ciprofloxacin was >18%; to ceftazidime >40%; and variable activity for cefepime, imipenem and meropenem. P. mirabilis did not present resistance to third- and fourth-generation cephalosporins or to carbapenem and quinolones. In the case of Enterobacter spp., a high sensitivity was shown to cefepime, imipenem, meropenem, aminoglycosides and nitrofurantoin (Table 1). E. faecalis was sensitive to nitrofurantoin and resistance to vancomycin was not documented. On the other hand, resistance of E. faecium was marked for ciprofloxacin and less for nitrofurantoin; 16.7% of the strains were resistant to vancomycin (Table 2).

4. Discussion

Uncomplicated acute febrile UTI has its maximum incidence during the first year of life in both sexes, whereas afebrile UTI occurs in children >3 years of age.22 After that age, infection confined to the bladder mucosa (cystitis) is accompanied, in general, by localized symptoms and can be easily recognized and treated. Temperature elevation and systemic manifestations increase the probability of kidney compromise.

There are two situations that are critical in antimicrobial treatment: the first is that the response to treatment be quick and effective and to facilitate the prevention of complications and recurrences. The second is to prevent the emergence of resistance to antimicrobial drugs prescribed according to dose, interval and duration.

In the last two decades a notable increase has been seen in the antimicrobial resistance of uropathogens, which complicates the specific selection of drugs, increases morbidity, elevates costs to reassess each case individually and decision to retreat, as well as greater use of broad spectrum antibiotics.23-28

Selection of the treatment scheme has been complicated as the resistance to uropathogens has increased worldwide. Before 1990, resistance of E. coli to TMP/SMX was found to be between 0 and 5%25; 5 years later increases of between 7 and 18% were reported,11,26-28 principally of E. coli in patients with cystitis. In a national study in the U.S., resistance of E. coli to TMP/SMX was 15% in 1995 and from 16-17% for 1998-2001.11 A similar study done in Spain and Portugal showed figures close to 35%.28 More recent published studies do not show that the panorama has improved.9-12

One aspect that should be taken into account is the huge geographical variation of antimicrobial sensitivity and resistance profiles. This situation is a limitation of the information which, as in this study, is published in the literature. Therefore, it is necessary that each institution gains from the experience in their area of work and that the data published, whether international or local, be taken as an orientation for beginning treatments.

The guides of the IDSA (Infectious Diseases Society of America)29 and AAP (American Academy of Pediatrics)10,30 have established the criteria for selection of drugs considered to be first line for the treatment of a UTI in their different presentations, taking into consideration the sensitivity/ resistance profiles specifically for E. coli, bacteria to which the empiric selection of treatment should be focused due to its preponderant participation in the etiology.

AAP considers that the treatment should be preferentially oral.10,30 When the patient has nausea or is vomiting or when adherence to the treatment scheme is not guaranteed, then parenteral treatment is justified, especially when the patient has the appearance of being severely affected, dehydrated or is unable to take oral medications.

From a practical point of view, both the parenteral and oral routes are equally effective and efficient. The selection of the drug depends on resistance present in each institution or region. A recent consensus in our country presents a multidisciplinary approach to the topic.2

Of the most relevant aspects of this study is that among Gram negative bacilli, cefepime, imipenem and meropenem were the most effective β-lactams (82-100%), with significant difference when compared with ceftazidime against K. pneumoniae and P. aeruginosa (p<0.05). Resistance to these broad spectrum drugs, according to the CLSI20 criteria, was in part related to the presence of ESBL in 26.8% of E. coli and 44% in K. pneumonia.31 This situation complicates the empiric treatment scheme even more and supports the option towards the prescription of other β-lactams of broader spectrum.8,9,11,12,15,23-27,31 However, before moving towards the third-generation cephalosporins, preferably oral, or towards the carbapenems, one must consider that in the case of E. coli there are other options. For example, nitrofurantoin has an excellent action against Gram negative bacteria such as E. coli, K. pneumoniae and Enterobacter spp.,as well as against E. fecalis. The particular limitation is related to the presence of P.aeruginosa, for which its activity is void.2,28

When compared with other published studies,8,9,11,12,15,23-27,31 resistance of E. coli to medications considered as first line (TMP/SMX and ciprofloxacin) is found in figures considered as elevated, from 73.7 and 33.8%, respectively.

The same happens with P. aeruginosa, where approximately 1/2 strains are resistant to ceftazidime and 1/10 are resistant to imipenem, cefepime and meropenem. Nitrofurantoin demonstrated a susceptibility >95% for E. coli, Enterococcus spp. and K. pneumoniae, which represent the largest percentage of the etiology for UTI.

Certainly, third-generation cephalosporins cover >90% of the pathogens; however, to begin treatment they should be selected based on the individual conditions of the patient. For example, AAP10,30 considers that children <2 years of age with febrile UTI can be prescribed third- generation cephalosporins orally, such as ceftibuten. It is necessary to emphasize that resistance to uropathogens had significant geographic variation, a reason why it is convenient to know the information that is generated at the institutional or regional level.

Enterococcus spp. occupied, by frequency, second place.

E. faecalis had sensitivity to glycopeptides (vancomycin) of 100%, a figure similar to that observed for nitrofurantoin. The presence of E. faecium, although not elevated (16/457, 3.5%), stood out due to the resistance it showed to vancomycin (16.7%). This implies that it could potentially be a source of transmission of different mechanisms of resistance to other bacterial species.

The results presented here confirm that resistance to uropathogens isolated from patients with community-acquired UTI is a serious problem and must specifically guarantee that the treatment initiated empirically will prevent recurrences, progression towards chronicity and, more seriously, renal damage.

To reduce treatment failures, not only of the acute un-complicated UTI but also the hospital-acquired infection, it is necessary to have an institutional antimicrobial resistance surveillance system that enables the selection of specific drugs according to dose, interval and duration. The information provided in this study will allow selecting the antimicrobial that may offer efficacy and safety.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest of any nature.

Received 29 June 2014;

accepted 28 October 2014

☆ Please cite this article as: López-Martínez B, Calderón-Jaimes E, Olivar-López V, Parra-Ortega I, Alcázar-López V, Castellanos-Cruz MC, et al. Susceptibilidad antimicrobiana de microorganismos causantes de infección de vías urinarias bajas en un hospital pediátrico. Bol Med Hosp Infant Mex. 2014;71:339-345

* Corresponding author.

E-mail: brisalm@yahoo.com.mx (B. López-Martínez).