Anti-vascular endothelial growth factor drugs are the treatment of choice for macular edema due to venous occlusions. While rare, they have been associated with some uncommon adverse effects. We present a case of retinal vasculitis associated with bevacizumab in a72-year-old woman who presented to our clinic with sudden visual acuity loss in her left eye due to macular edema following central vein occlusion. She was treated with bevacizumab, with a minor inflammatory response that resolved with topical steroids. After 6 weeks, the macular edema recurred and a 2nd dose of bevacizumab was indicated, with a severe inflammatory reaction that resolved with periocular steroids and topical NSAIDs. Systemic vasculitis and infectious diseases were ruled out and treatment was switched to aflibercept with no adverse effects being reported.

Los fármacos anti-Factor de Crecimiento Vascular Endotelial son el tratamiento de elección para el edema macular secundario a oclusión venosa; aunque sus efectos secundarios han sido previamente descritos, estos suelen ser raros. A continuación, presentamos un caso de vasculitis retiniana asociada a bevacizumab en una paciente de 72 años que acudió a consulta por edema macular secundario a oclusión de vena central de la retina, por lo que fue tratada con bevacizumab intravítreo, posteriormente presento una respuesta inflamatoria mínima que fue resuelta con esteroides tópicos. 6 semanas después se detectó recurrencia del edema macular por lo que se aplicó una segunda dosis de bevacizumab, en esta ocasión con una respuesta inflamatoria severa que requirió tratamiento con esteroides paraoculares y antiinflamatorios no esteroideos tópicos. Se descarto la presencia de vasculitis sistémica y enfermedades infecciosas y se decidió cambiar el tratamiento intravítreo a Aflibercept, con el que no se presentaron efectos adversos.

Intravitreal injection of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is the most frequently performed intraocular procedure.1 The therapeutic spectrum of these agents continues to grow; their indications include exudative macular degeneration, diabetic macular edema, and macular edema due to retinal venous occlusion. The anti-VEGFs currently in use include bevacizumab, ranibizumab, aflibercept, and brolucizumab. Since their inception, their safety and potential associated complications have been the research topic.2

Concerns about the associated complications, particularly those related to non-infectious inflammatory events, have recently regained interest due to increasing incidence rates.3 Notably, there is very little understanding on the mechanism of action of newly developed anti-VEGF compounds. Gaining a better clinical and evolutionary understanding of these drugs will help clarify risk factors, pathophysiology, and therapeutic logic. It will also allow us to prevent, diagnose, and treat side effects, thus reducing their impact on the patients' visual outcomes.

We report the first case of non-infectious intraocular inflammation, clinically showing as retinal vasculitis associated with the use of intravitreal bevacizumab for the treatment of macular edema due to central retinal vein occlusion.

Case reportA 72-year-old female patient presented to our clinic with a 15-day history of sudden decrease in visual acuity in the left eye. She had a past medical history of arterial hypertension and cataract surgery in both eyes.

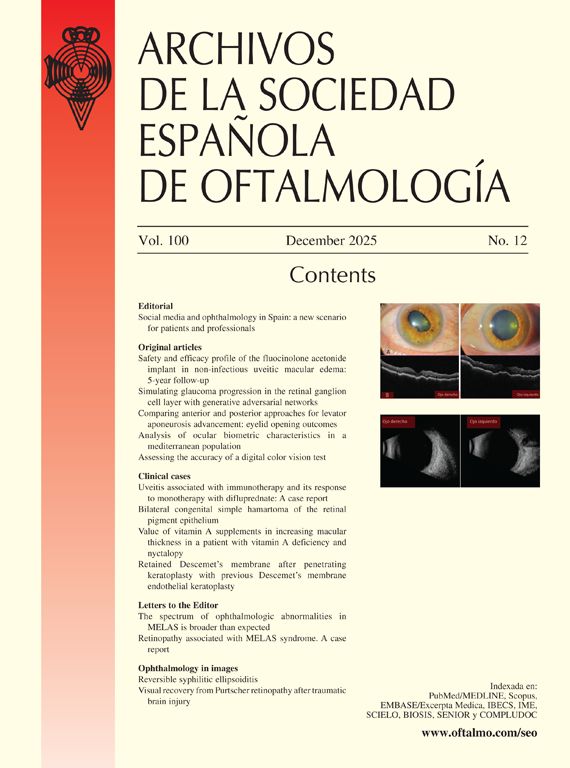

Ophthalmological examination revealed best-corrected visual acuities of 20/25 and 20/80 in the right and left eye, respectively. Biomicroscopy showed transparent media, pseudophakia in both eyes, and isochoric, photoreactive pupils. Fundoscopic examination of the right eye revealed normal findings. Her left eye contained multiple dot and blot hemorrhages in all 4 quadrants. There was also generalized vascular dilation and tortuosity, predominantly of venous vessels, and an absence of the foveal reflex (Fig. 1a). Optical coherence tomography (OCT) showed a severe cystoid macular edema on the right eye (Fig. 1b).

a. Retinography shows multiple retinal dot hemorrhages, vascular tortuosity, and absence of foveal reflex. b. Baseline macular ocular coherence tomography (OCT) showing the presence of cystoid macular edema. c. OCT 48 hours after the injection showing hypereflective spots on the vitreous interphase and resolution of the edema.

The patient was diagnosed with central retinal vein occlusion with secondary macular edema and was referred to internal medicine/cardiology for evaluation and control of systemic risk factors. An intravitreal injection of bevacizumab (1.25 mg/0.05 cc) was administered in the left eye based on our clinic protocol and after obtaining the patient’s signed informed consent form. Topical antibiotic prophylaxis was not administered, neither prior nor after the injection. In the follow-up visit conducted 24 hours after the procedure, the patient remained asymptomatic. However, clinical examination revealed mild conjunctival hyperemia and grade I flare, transparent vitreous, and no retinal changes. Due to mild signs of anterior intraocular inflammation, a combination of topical antibiotics and steroids (tobramycin and loteprednol) was administered, resulting in complete resolution of anterior segment inflammation signs. A best-corrected visual acuity of 20/40 was registered. An OCT performed 48 hours after the injection showed a reduction of cystoid edema, but hyperreflective dots within the vitreous cavity were also noticed (Fig. 1c).

Six weeks after the first therapy was administered, the patient returned with improved clinical appearance, partial remission of dot hemorrhages, and a decrease in visual acuity (20/70) due to recurrence of cystoid macular edema. A 2nd dose of intravitreal bevacizumab was administered. The patient returned for a follow-up visit 24 hours later, reporting no pain or changes in visual acuity, photopsias, or myodesopsias. There were, however, signs of inflammation, with ciliary injection (+1), flare (+1), AC cells (+1), and vitritis (+1). Vitreous condensations were also observed. The patient was treated with topical fluorometholone. The patient remained asymptomatic 73 hours later. A slight improvement in visual acuity was observed (20/40), along with remission of hyperemia and flare. However, AC cells (+1) and vitritis (+1) remained, with vascular sheathing being noticed in the mid-periphery of all 4 quadrants, predominantly in the nasal and upper temporal quadrants, and close to the posterior pole in the inferotemporal quadrant. Fluorescein angiography showed mild perivascular filtration in the late phases and areas of hypoperfusion in the nasal peripheral retina. Although OCT confirmed remission of the macular edema, there was an increase in the hyperreflective dots suspended in the vitreous cavity as well as on the retinal surface (Fig. 2).

a. Wide-field retinography performed after the administration of the 2nd dose of bevacizumab showing generalized vascular sheathing (black arrows). b. Late phases of fluorescein angiography (FA) showing mild perivascular filtration in vascular sheathing areas, primarily at the nasal retina. c. Optical coherence tomography showing remission of the macular edema.

Additional laboratory tests for vasculitis screening, including ELISA for Toxoplasma gondii, HIV, Herpes virus, and cytomegalovirus; VDRL test; biometry; glycemia; protein electrophoresis; angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) level measurement; immunological profile (PCR, ESR, RF, ANA, anti-DNA, anti-CCP, ANCA c, and ANCA p); QuantiFERON-TB Gold Plus test; and chest X-rays were performed, with no significant results being noticed.

Since the patient experienced no other conditions, 2 doses of 0.8 mL of periocular betamethasone phosphate were administered 1 week apart. Fluorometholone was continued, and topical nepafenac was added. Gradually, her condition improved, with OCT revealing the disappearance of vitreous cells. Additionally, a decrease of vitritis and vascular sheathing was noticed (Fig. 3a). Five weeks after the resolution of inflammation, the patient’s macular edema came back (Fig. 3b). This time, treatment was switched to 2 mg/0.05 mL of intravitreal aflibercept. The patient showed no signs of inflammation and no clinical or tomographic reactivation. At the 7-week follow-up, the edema had disappeared, and the patient’s visual acuity recovered to 20/40 (Fig. 3c).

a. Wide-field retinography showing resolution of vascular sheathing after the administration of periocular steroids and non-steroid topical anti-inflammatory drugs. b. Recurrence of cystoid macular edema (CME), as observed by optical coherence tomography c. Resolution of CME after a single dose of aflibercept at the 7-week follow-up.

As far as we know, this is the first reported case of non-infectious intraocular inflammation clinically showing as retinal vasculitis associated with the use of intravitreal bevacizumab for the treatment of macular edema due to central retinal vein occlusion.

Bevacizumab is well known as an effective anti-VEGF treatment for various conditions, including macular edema due to retinal vein occlusions. While its intraocular use is considered off-label, it has been approved under local regulations. Additionally, its favorable cost-benefit ratio positions it as the first-line therapy for these patients. The reported incidence rate of adverse events associated with intravitreal bevacizumab use does not exceed 0.21%, as reported per an extensive international survey.3 The occurrence of non-infectious intraocular inflammation (uveitis) is even rarer, at 0.09%.4 However, patients who develop secondary uveitis exhibit similar clinical symptoms as reported in other case series, including aqueous flare and cells in the anterior chamber (pseudogranulomatous iridocyclitis),5 hypopion6 and varying degrees of vitritis.7 In comparison, the rate of non-infectious intraocular inflammatory events associated with other molecules, especially brolucizumab, has been found to be significantly higher, including retinal vasculitis among this events.8

Based on its presentation and clinical features, we classify this case as a non-infectious event. The patient did not report pain or decreased visual acuity, which are typical symptoms of infectious endophthalmitis.9 Inflammation responded well to topical steroids, and the resolution of symptoms correlated with the clearance of bevacizumab from the vitreous body.

We hypothesize that the immune response was induced by individual patient factors in direct response to bevacizumab, based on the following aspects:

The patient had no predisposing factors such as a past medical history of uveitis or treatment with topical pro-inflammatory drugs. Additional workup was performed and there was no evidence of systemic inflammatory disease during the ocular condition. Other factors commonly associated with sterile inflammatory responses, such as drug contamination by exotoxins, non-human proteins, impurities, or silicone particles from the syringe enhancing the drus immunogenic effect,9 were considered unlikely. The injected compounds were obtained directly from the manufacturer’s bottle with no reconstitution or additional manipulation. Additionally, a total of 12 patients received injections simultaneously during the patient’s first treatment, and 14 more patients were treated in a 2nd group using identical supplies and a similar technique. No other adverse effects were observed in these subjects.

The presence of anti-idiotypic antibodies may provide a plausible explanation for the immunological mechanism observed in this case. It has been documented that these antibodies can exist prior to exposure to monoclonal antibodies,7 and their production and activity can increase upon repeated exposure to an antigen. Bevacizumab structural characteristics, including an Fc component, make it susceptible to triggering an immunogenic response.10 Under such circumstances, a type III hypersensitivity response may occur, involving the formation of antigen-antibody immune complexes. These complexes could potentially precipitate on retinal vessels, activating complement proteins, recruiting inflammatory cells, and releasing lysosomal enzymes and free radicals. These effects can lead to structural and functional damage.

In systemic bevacizumab treatment, a type III delayed hypersensitivity response mediated by IgG can show as nephropathy and vasculitis with IgA-mediated nephritis.11 Typically, immune complexes form in the circulatory system before tissue deposition. While the eye is an immune-privileged site where this process is less likely, disruption of the blood-retinal barrier due to vascular events may contribute to the formation of anti-idiotypic antibodies. This mechanism could potentially explain the clinical findings seen in our patient. In the case of brolucizumab, the development of vasculitis has been attributed to a mechanism of delayed hypersensitivity, which is triggered by the formation of immune complex due to the presence of local antibodies.8

A type IV hypersensitivity mechanism, mediated by sensitized T lymphocytes, presents another possible explanation. This type of hypersensitivity is commonly associated with occlusive and hemorrhagic retinal vasculitis seen in treatments involving vancomycin and brolucizumab.12 However, the more aggressive clinical course observed in those cases differs from our patient's experience.

Of note, brolucizumab smaller size, molecular weight, and higher molar concentration facilitate greater tissue penetration and prolonged exposure to the immune system. In contrast, bevacizumab, with its larger molecule, has limited penetration and effect. Nevertheless, the larger molecule of bevacizumab also reduces exposure to the immune system, although it doesn't completely rule out this mechanism.

Concerns about the associated complications, particularly those related to non-infectious inflammatory events, have recently regained interest due to increasing incidence rates. Notably, there is very little understanding of the mechanism of action of newly developed anti-VEGF compounds. Gaining a better clinical and evolutionary understanding of these drugs will help clarify risk factors, pathophysiology, and therapeutic logic. It will also allow us to prevent, diagnose, and treat side effects, reducing their impact on patients' visual outcomes.

ConclusionsIntraocular inflammation due to intravitreal bevacizumab use is uncommon but possible. Its severity and presentation vary among individuals. This patient showed retinal vasculitis, which, although benign and non-ischemic, required treatment and follow-up. Even mild clinical and paraclinical signs of inflammation should be closely monitored, as they may signal sensitization to the compound, requiring further treatment.

The drug therapeutic effect may remain unchanged despite the immunogenic response. Although switching to a new anti-VEGF compound is a viable alternative, it may heighten the risk of an increased immune response or cross-sensitivity. Steroids can be used concurrently as a therapeutic option for managing both the inflammatory reaction and the underlying condition.

Ethical approvalEthical approval for this study was obtained from our enter ethics committee (CDO ethics committee) with approval No.: MLSA2021_3BS.

Statement of informed consentWritten informed consent was obtained from the patient.

None declared.