In laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC), the treatment of iatrogenic biliary tract injury has been given much attention. However, most accidental right hepatic artery (RHA) injuries are treated with simple clipping. The reason is that the RHA has difficulty in revascularization, and it is generally considered that RHA injury does not cause serious consequences. However, some studies suggest that some cases of RHA ligation can cause a series of pathological changes correlated to arterial ischemia, such as liver abscess, bile tumor, liver atrophy and anastomotic stenosis. Theoretically, RHA blood flow should be restored when possible, in order to avoid the complications of right hepatic ischemia. The present study involved two patients, including one male and one female patient. Both patients were admitted to the hospital with the diagnosis of chronic cholecystitis and gallbladder stone, and developed ischemia of the right half hepatic after accidental transection of the RHA. Both patients underwent continuous end-end anastomosis of the RHA with 6-0 Prolene suture. After the blood vessel anastomosis, the right half liver quickly recovered to its original bright red. No adverse complications were observed in follow-ups at three and six months after the operation. Laparoscopic repair of the RHA is technically feasible. Reconstruction of the RHA can prevent complications associated with right hepatic ischemia.

The pathological mechanism of iatrogenic bile duct injuries in laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) and the prevention and management of bile duct injuries have been extensively studied. However, little attention has been given to vascular injury (mainly for the right hepatic artery [RHA]) [1,2]. At present, the treatment of RHA injuries remains controversial. The investigator consulted relevant literatures [3,4] and found several cases of RHA injury, which turned to open abdominal reconstruction. Merely one case of laparoscopic repair of RHA lateral wall injury was reported. In six months, two patients underwent laparoscopic repair of the RHA after transection in our center, and achieved good results. The details are reported as follows.

2Case history2.1General informationThe present study involved two patients, including one male and one female patient. The female patient was 48 years old, while the male patient was 56 years old. Both patients were admitted to the hospital due to “repeated right upper quadrant pain”. Combined with preoperative ultrasonography, it was diagnosed as chronic cholecystitis with gallbladder stone. No computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) were performed. No preoperative contraindications were revealed in routine preoperative examinations. LC was performed for both patients.

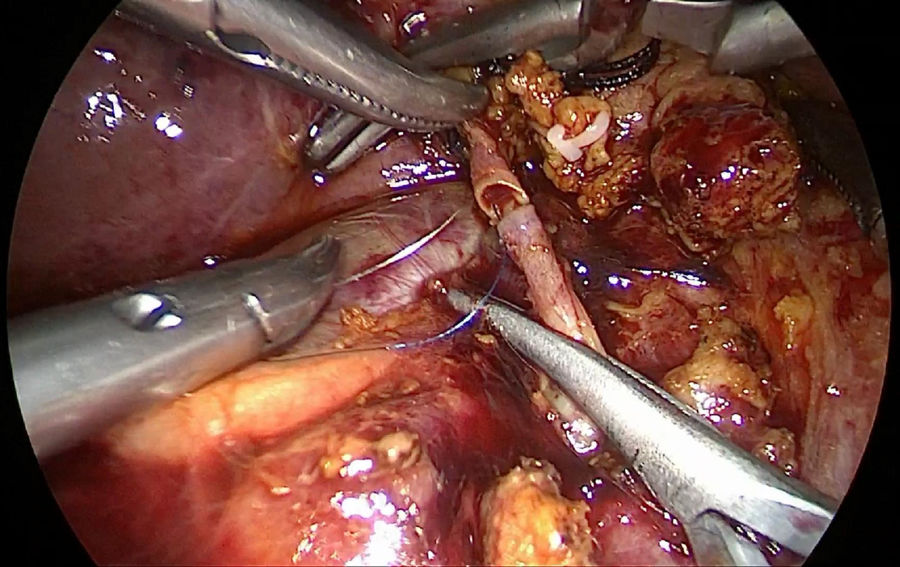

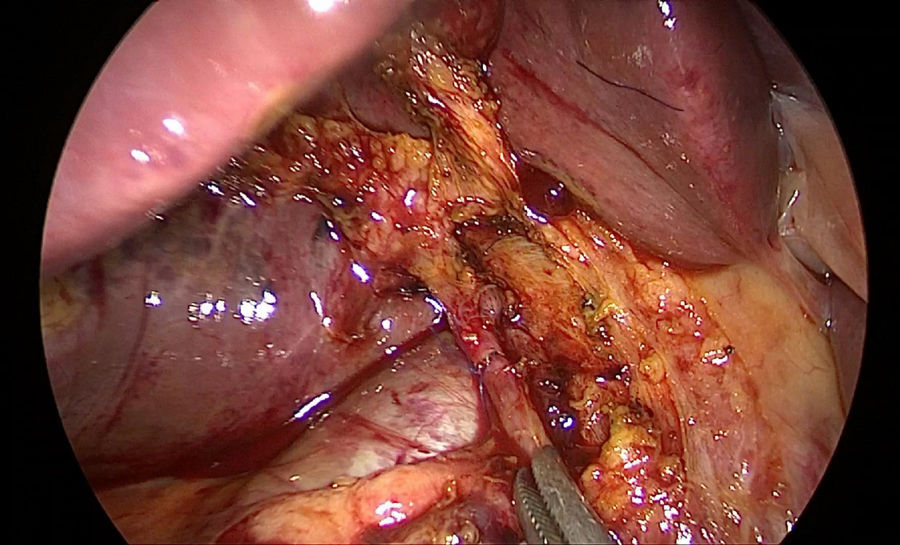

2.2Surgical procedures and processPatients received general anesthesia and endotracheal intubation, drugs were routinely sent into the abdomen from the ports at the right upper abdomen using the three-port technique. Inspection of the abdominal cavity was performed before LC. In the female patient, the anatomy in the conjunction between the cystic duct and common bile duct was unclear, the excessively tractioned common hepatic duct with small diameter was transected by error due to mistaking it for cystic duct, and the RHA in a deep position was transected due to mistaking it as the cystic artery. In the male patient, the RHA parallel above the cystic duct was mistaken as the gallbladder artery due to absence of careful dissection. Hence, the RHA was transected and caused injury. Both patients were aware of the RHA injury only when there was still high pressure in the distal part of the RHA and an ischemic line appeared in the right half of the liver. After consulting more experienced doctors on the operating table, the surgeon decided to perform laparoscopic repair of RHA: one 5-mm Trocar port was additionally made at the right upper quadrant and left upper quadrant, respectively, the distal and proximal ends of the cut RHA were separated for at least 1cm, the proximal Hem-o-lock clip was removed, vascular ends were temporarily blocked with titanium clips or the endoscopic pug dogs, and the stumps were trimmed properly with scissors to determine whether the vascular cut ends could receive the tension-free anastomosis. Then, continuous end-end anastomosis of the RHA was performed with 6-0 Prolene suture (Figs. 1 and 2). After opening the RHA, the right half liver quickly recovered to its original bright red. The female patient suffered from common hepatic duct injury, and was treated with end-end anastomosis of stumps of the common hepatic duct after trimming and placement of the “T” tube in the common bile duct.

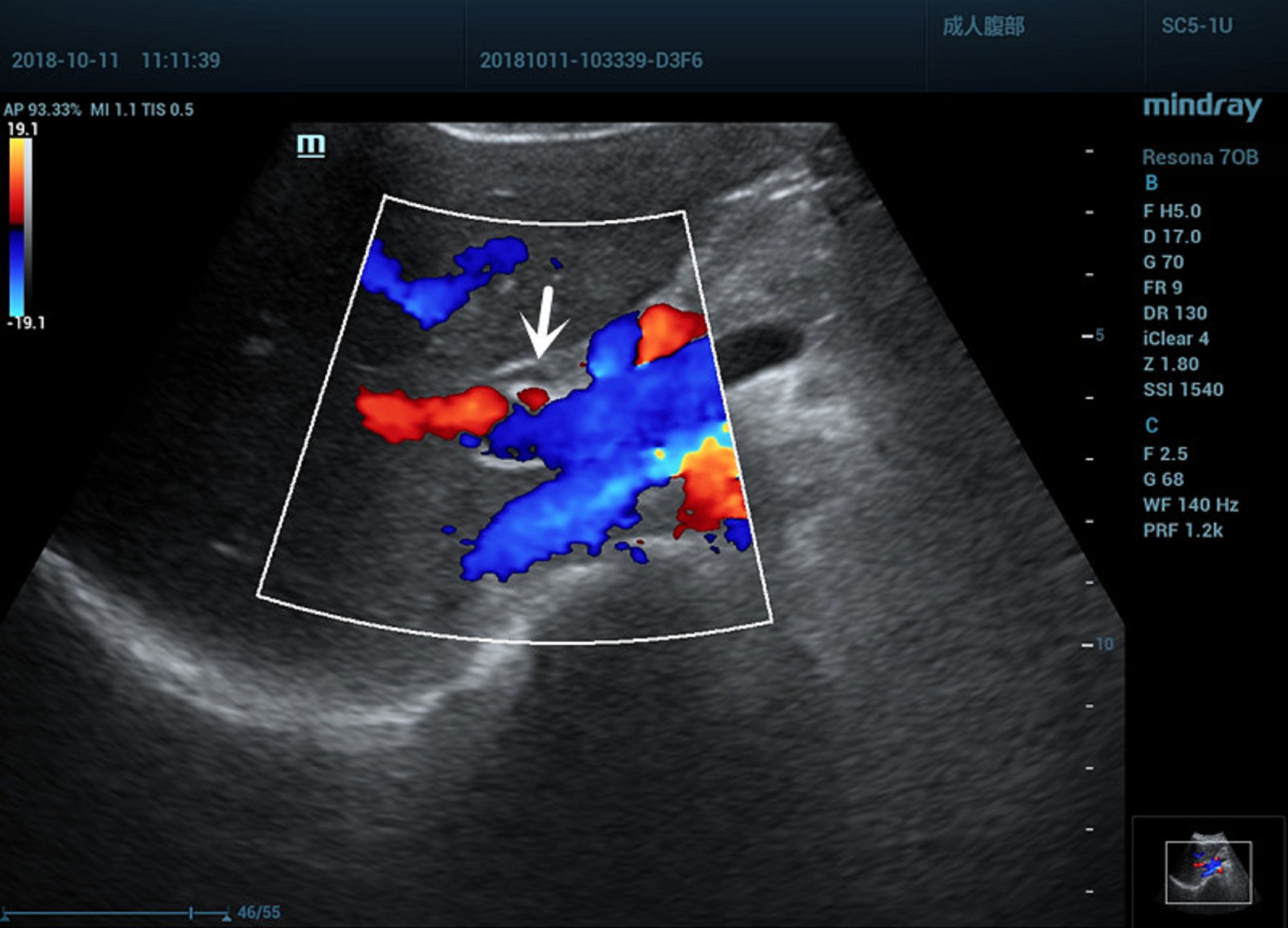

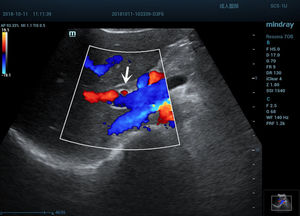

2.3ResultsThe time for RHA end-end anastomosis in the male patient was 30min, the time for RHA end-end anastomosis in the female patient was 35min, the time for common hepatic duct anastomosis and T tube placement in the common bile duct was 25min. After opening of the RHA, the right half liver quickly recovered to its normal color and luster. After the operation, in both patients, the level of transaminase slightly increased, but did not exceed three times the normal value, while the levels of total bilirubin and direct bilirubin did not increase. Patients received liver-protecting symptomatic treatment for 3–5 days. Their liver functions basically returned to normal, and the patients were discharged from hospital on postoperative days five and six, respectively. At follow-up one month after the operation, no special discomfort was found in these two patients, ultrasonography revealed smooth portal RHA blood flow (Fig. 3), and revealed no liver abscess, no liver atrophy and no abnormal change in intrahepatic bile duct diameter. The female patient was followed-up at three months and six months after the operation. No abnormalities were found by routine blood test, liver function test, B ultrasound and T tube angiography, and the T-tube was removed at six months after the operation. The patient was instructed to be followed-up in the Outpatient Department after half a year. The male patient was followed-up at three months after the operation and no abnormalities were found. The patient was instructed to be followed-up in the Outpatient Department half a year after the operation.

3DiscussionCombined hepatic artery injury is a special type of iatrogenic biliary tract injury in LC. This injury mostly manifests as RHA injury. Literatures have reported that [5,6] hepatic artery injury accounts for 6.7–61% of the total biliary tract injuries. The reason for this statistical difference may be the difference in diagnostic methods or the missing of some cases of hepatic artery injury. The causes of RHA injury mainly include anatomic abnormalities, pathological changes, and artificial and technological factors [7–9]. If surgeons are unfamiliar with or do not pay attention to variations of the RHA, in the case of acute and chronic cholecystitis with unclear anatomy of the Calot triangle, RHA may be accidentally injured or the RHA may be mistaken for the cystic artery and be actively cut off. In the present study, both the mechanisms of injury in these two patients were transection of the RHA trunk due to mistaking this as the cystic artery. Its characteristic feature is the relative thickness in the so-called cystic artery, which has been cut off. This leads to high pressure of arterial outflow after distal electrocoagulation disconnection, the right half liver presents with an obvious ischemia line in a short time, and further tracing reveals that the vascular distal end enters the right liver. Although in recent years, digital 3D imaging techniques have been helpful in the preoperative judgment of abnormal RHA distributions and avoidance of intraoperative accidental injury caused by anatomical variations, it remains unrealistic for LC patients to receive complex imaging examinations. Familiarity with anatomy, improvement of technology and vigilance may be the keys to avoid accidental injury to the RHA [10–12], especially when it is found that the so-called “cystic artery” in the Calot triangle is relatively larger. If the diameter is more than 2–3mm, the operator should be aware of the possibility of RHA.

For the treatment of RHA injury during LC, there are many uncertainties and controversies in present researches [13]. Some studies suggest that RHA ligation may cause a series of pathological changes related to arterial ischemia, such as liver abscess, bile tumor, liver atrophy and anastomotic stenosis. For example, Li reported that [14] in 10 patients with biliary tract injury and arterial injury, three patients presented with liver atrophy, liver abscess and other manifestations. These changes may also be evidenced by complications induced by interventional therapy for liver cancer or vascular injury in hilarcholangiocarcinoma [15,16]. Some experts consider that the liver has double blood supply. After injury of a single RHA, the right half liver can receive collateral circulation from the uninjured left hepatic artery to restore blood supply through the portal area and perihepatic ligament. Therefore, complex RHA repair is not necessary. Yi Yu reported that [10] three patients with RHA injury who underwent LC were followed up for one year, and no abnormalities were found. The review of Strasberg SM also suggested that [8] only 10% of patients with RHA injury would develop right hepatic infarction, and it was considered that it was difficult to repair RHA, and that the effect was not significant. The author considered that the occurrence of serious complications after RHA injury may be correlated to the site of vascular injury and the presence of biliary tract injury. For example, vascular injury of the confluence site complicated with transection of the bile duct at a high position will destroy the blood supply from left to right, and the vascular plexus on the surface of the biliary tract may accordingly lead to right hepatic ischemia and necrosis, or the failure of biliary tract repair. In the present study, an obvious right hepatic ischemia line appeared in both patients after RHA injury. One patient was complicated with transection of the common hepatic duct. In this case, the blood flow of RHA should be restored as much as possible. Theoretically, this can avoid possible long-term complications, such as right hepatic ischemia and biliary stenosis.

National and international literatures have revealed that [4,10,17,18] limited by equipment and technical experience, most patients with RHA injury during LC cannot undergo arterial reconstruction, very few patients completed the reconstruction after turning to open surgery, and only one patient with RHA lateral wall injury underwent reconstruction under a endoscope. The author considers that the magnification of endoscopy can display the RHA and help judge the inflammation of local tissues more clearly, when compared to open surgery. If a patient has the conditions for RHA end-end anastomosis, RHA reconstruction can be completed under a laparoscope. Indeed, this requires a skilled vascular stitching technique and teamwork. In the present study, two patients underwent continuous end-end anastomosis of the RHA with 6-0 Prolene suture, the time for separation of the surrounding blood vessels and anastomosis was approximately 30min. After opening of the RHA, the right half liver quickly recovered to its original bright red, and the effect was rapid and significant. The female patient suffered from common hepatic duct injury, and was treated with suture of stump of common hepatic duct after trimming and placement of the T tube in the common bile duct. The T tube was removed six months after the operation, and no adverse complications occurred at present. The male patient had been followed up for three months and no abnormalities were found.

The investigators succeeded in the anastomoses of the RHA under an endoscope. This suggests that the laparoscopic repair of RHA is completely feasible. Indeed, the number of cases in the present study was small and the follow-up duration was short. Hence, meaningful long-term conclusions could not be drawn.AbbreviationsLC laparoscopic cholecystectomy right hepatic artery computed tomography magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography

Bao-Qiang Wu been involved in drafting the work and revising it critically for important intellectual content; Jun Hu made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work; Wen-Song Liu, Yong Jiang and Dong-Lin Sun made substantial contributions to the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data for the work; Xue-Min Chen given final approval of the version to be published.

Informed consentInformed patient consent was obtained for publication of the case details.

FundingNo financial support.

Conflicts of interestNone of the authors have any financial disclosure or conflict of interest.