Chronic liver disease (CLD) is characterized by progressive deterioration of liver function. This process is characterized by the induction of inflammation and destruction and scarring of the liver parenchyma [1]. The most common CLDs worldwide are hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), alcohol-related liver disease (ARLD), autoimmune liver disease (AILD), and more recently, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) [2]. Mexico has the highest prevalence of compensated and decompensated cirrhosis in the Americas [2].

However, studies on the incidence of CLD in Mexico are scarce. From 1980 to 2010, mortality related to CLD increased by 46 % worldwide [3]. According to the National Institute of Statistics and Geography, liver disease is the fourth place as one of the main causes of death in Mexico [4].

The prevalence of HCV in Mexico has remained at 1.4 % over the last decade, with a viremia rate ranging from 0.27 % to 1 %, corresponding to an estimated 1.6 million infected individuals [5]. By 2018, the prevalence of anti-HCV antibodies in northern Mexico was reported at 0.5 % in a population of 50-year-olds, which matched the national prevalence of 0.5 % in this group. In the 20 to 49-year-old population, the prevalence of anti-HCV antibodies in northern Mexico was 0.1 %, while the national prevalence for this age group was 0.2 % [6]. According to the 2020 Annual Epidemiological Surveillance Report, an average of 2108 new HCV cases per year was recorded between 2010 and 2020, with an incidence rate of 1.06 cases per 100,000 inhabitants [7].

In 2019, HBV was responsible for 820,000 deaths globally. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that 296 million people had chronic HBV infection in 2019. Eighty-eight percent of the global HBV burden can be found in Africa, Southeast Asia, and the Western Pacific [8]. The prevalence of HBV in Mexico is low, at <2 %. It has been reported that the percentage of the population carrying HBsAg is between 0.2 % and 0.5 % [9]. In 2022, the global prevalence was estimated to be 257 million infected individuals, with an estimated incidence of 1.5 million new cases per year [10].

Northern Mexico has one of the highest prevalences of binge drinking, ranging from 21.8 % to 27 %, with the national prevalence being 16.4 % [6]. The State of Nuevo León has a consumption per capita (among 15- to 65-year-olds) of 7.4 L of pure alcohol while the national average consumption is 4.9 L (men, 7.9 L; women, 2.1 L) [11]. The reason for this issue is multifactorial; however, some studies suggest that social disadvantages related to migration (due to proximity to the United States border), poverty, and living in underserved neighborhoods represent a clearly identified risk factor in the northern part of the country [12].

In 2016, the global prevalence of MASLD was estimated at 25 %, with associations to comorbidities such as obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), hypertriglyceridemia (HTG), hypertension, and metabolic syndrome (MetS), with an estimated T2DM prevalence of 43.6 % [13].

In northeastern Mexico, an increase in T2DM prevalence has been reported, rising from 7.6 % in 2006 to 14.3 % in 2020, representing a significant risk factor for the development of MASLD and cirrhosis [14,15]. Additionally, according to the 2018–2019 National Health Survey, the main factors associated with a higher prevalence of obesity include low socioeconomic status, living in food insecurity conditions, short stature, and female sex. Furthermore, the heterogeneity of the sociocultural and economic context, along with the availability of region-specific foods, may contribute to the high obesity rates reported in northern Mexico, reaching up to 41.6 % [14].

Hispanic populations have been shown to have a genetic predisposition to developing HTG [16]. The prevalence of MASLD varies among ethnic subgroups, being highest in Mexicans (22 %), followed by Central Americans (21 %), Cubans and Puerto Ricans (16 %), and Dominicans (15 %) [17]. These ethnic differences are attributed to visceral fat distribution [12] and the presence of genetic polymorphisms in genes such as PNPLA3, NCAN, LYPLAL1, GCKR, and PPP1R3B [18–20].

The main AILD include autoimmune hepatitis (AIH), primary biliary cholangitis (PBC), and overlap syndrome (OS). In Mexico, studies on AILD are limited. The reported prevalence of AILD ranges from 8.5 % to 17.1 % [21,22]. Valdivia et al. reported that, in a cohort of 67 patients with ALD, 57 % had AIH, 25 % had PBC, and 16 % had OS [21]. Similarly, a previous study conducted by our group, in a sample of 131 patients with ALD, found that 56 % had AIH, 27 % had PBC, and 17 % had OS [23]. It is important to highlight that when applying the revised International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group (R-IAIHG) classification for AIH and comparing it with the simplified scoring system, the latter showed a higher rate of false negatives. In contrast, the R-IAIHG classification demonstrated better performance, with superior sensitivity and specificity [23].

The objective of this study was to analyze the situational panorama of CLD and the presence of cirrhosis in these conditions over a 25-year period at the Hepatology Center of the “Dr. José Eleuterio González” University Hospital, Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León (UANL), recognized as the largest public hospital in the northeastern region of Mexico.

2Materials and methods2.1Patient selectionA retrospective, observational, and cross-sectional study was conducted, including 2679 patients with CLD treated at the Hepatology Center of the Department of Internal Medicine at the “Dr. José Eleuterio González” University Hospital, a tertiary care medical center with over 700 beds, located in Monterrey, Nuevo León, Mexico. This public hospital is the largest in northeast Mexico, and its patients primarily come from the state of Nuevo León and surrounding states in northern Mexico and southern Texas.

The Hepatology Center was established in 1983 and serves as a national referral center for liver diseases. It has a specialized laboratory and an outpatient clinic. In the context of this study, medical records have been managed in physical format since the unit's inception, as no electronic system is available. Each patient has a handwritten medical record with a unique identification number, where laboratory results and imaging studies are archived. Additionally, since 2003, a digital registry has been implemented using an Excel database, which is updated annually.

All medical records of patients who visited the outpatient Hepatology Center for the first time between January 1995 and December 2019 were reviewed. The diagnosis of CLD was made according to international guidelines [8,24–28]. Obesity was considered a risk factor in the cohort through the calculation of body mass index (BMI). The inclusion criteria were age over 18 years and a diagnosis of CLD with or without cirrhosis; this was assessed through liver biopsy and non-invasive methods for measuring fibrosis. The exclusion criteria were acute liver disease, other etiologies, non-chronic liver disease, and patients under 18 years of age. Three groups were established based on three time intervals for analysis: group A, 1995–2003; group B, 2004–2011; and group C, 2012–2019.

The diagnosis of AIH was based on the R-IAIHG criteria [29]. For classification, the results of the following autoantibodies were analyzed: antinuclear (ANA), smooth muscle (SMA), liver-kidney microsomal (LKM), and antimitochondrial (AMA). When available, the diagnosis was supplemented with the detection of AMA type 2 and ANA gp210. Since 2000, the laboratory of the Hepatology Center has offered tests to detect autoantibodies, including ANA, SMA, AMA, AMA2, and soluble liver antigen (SLA), performed by immunofluorescence. Between 2011 and 2013, the ELISA technique for LKM and AMA2 was added. This information has contributed to improving the diagnostic performance of AILD.

2.2Statistical analysisThe results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation for the numerical variables and categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to determine if there were differences between the independent groups, with Tukey’s post hoc test. Categorical variables were analyzed using the Pearson chi-square test. The analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 7.04 (San Diego, CA, USA). A p-value < 0.05 was considered significant.

2.3Ethical statementThis study was approved by the Ethics Committee of our institution (HI21–00,001) on May 25, 2021. It is important to note that, in retrospective studies, the requirement for informed consent is waived, as personal data are de-identified beforehand and no medical interventions are performed on the patients.

3ResultsThe Hepatology Center is a referral center for liver diseases in northeast Mexico, where 60 % of patients come from the state of Nuevo León, followed by the states of Tamaulipas, Coahuila, Chihuahua, San Luis Potosí, Sinaloa, Sonora, Mexico City, Veracruz, and Chiapas, primarily. This was a situational analysis study of patients with CLD evaluated over a 25-year period and it was not conducted on a population-wide basis.

Between 1995 and 2019, a total of 4483 patients were treated, of whom 2679 met the inclusion criteria and were enrolled in the study. The median age was 52 years (interquartile range: 40–60), and 1376 of them (51 %) were men. Obesity was considered a relevant risk factor across the entire cohort, with a BMI greater than 25 Kg/m2 observed in 72 % of the patients included in this study.

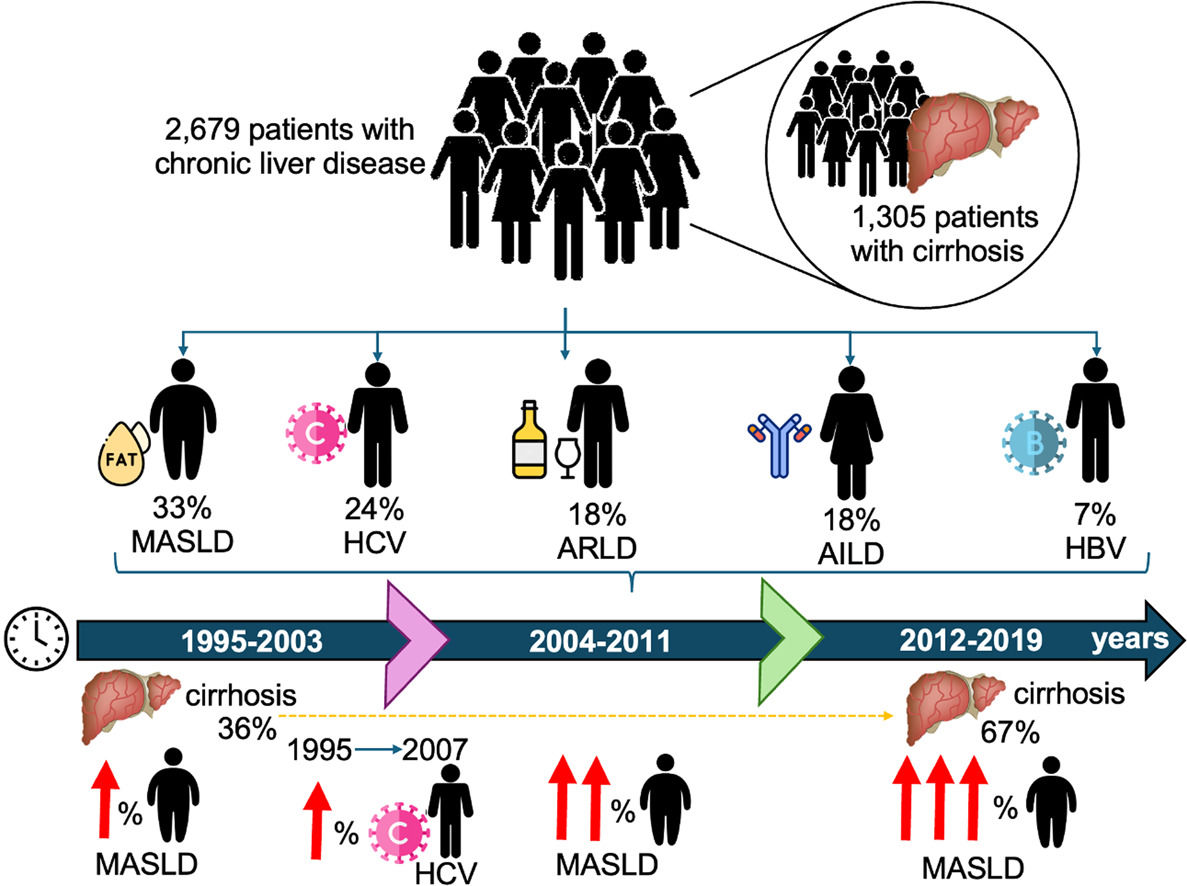

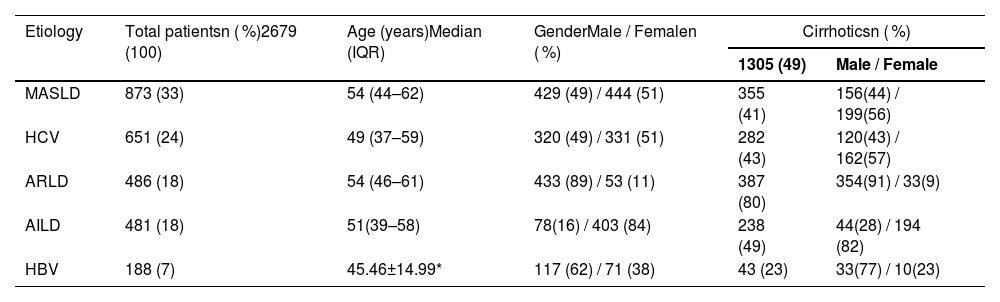

The distribution of CLD was as follows: MASLD, 873 patients (33 %); HCV, 651 (24 %); ARLD, 486 (18 %) of whom 95 % were MetALD, Metabolic dysfunction–associated alcohol-related liver disease; AILD, 481 (18 %); and HBV, 188 (7 %). Overall, cirrhosis was observed in 1305 of the 2679 patients (49 %) at the time of admission.

AILD included 481 patients with a mean age of 48.5 ± 13.7 years, with 17 % being over 60 years old. The distribution of diagnoses was as follows: AIH in 303 patients (63 %), PBC in 149 patients (31 %), and OS in 29 patients (6 %). Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) and IgG4-related cholangiopathy were not included due to their low prevalence in our population. Autoantibody testing at admission was available in 95 % of AIH cases, 83 % of PBC cases, and 93 % of OS cases. Among AIH patients, 95 % tested positive for ANA and/or SMA (≥1:80), and 11 % tested positive for LKM. In PBC, 80 % were AMA-positive, and of these, 48 % were also positive for AMA2. Among OS patients, 68 % tested positive for ANA and 69 % for AMA, with half of these being positive for AMA2.

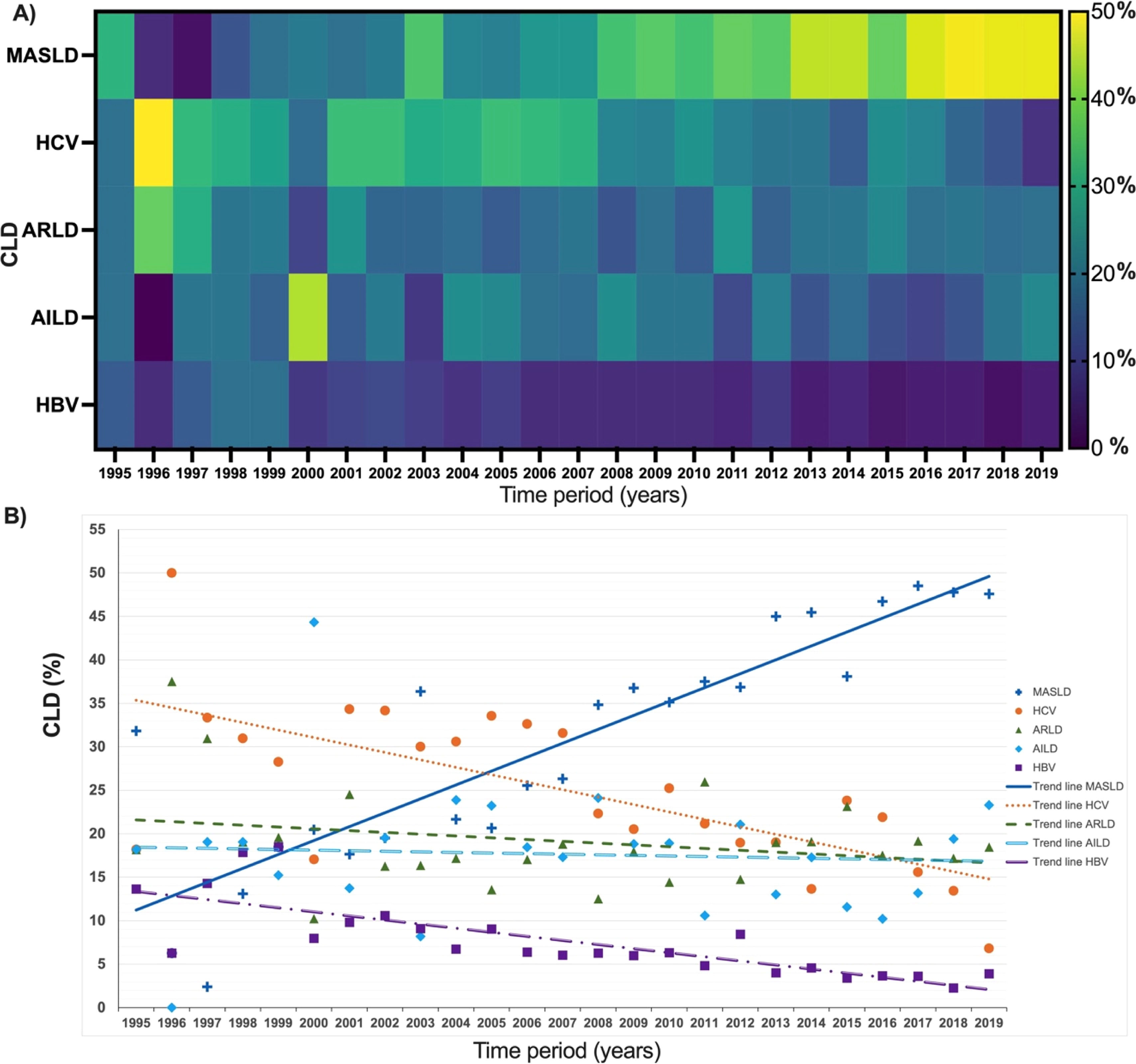

In Fig. 1A, the percentages of the five etiologies analyzed over the years are shown, while Fig. 1B highlights the trend of each. It was observed that from 1995 to 2007, the predominant CLD was HCV. However, starting in 2005, MASLD showed an annual increase, becoming the most common CLD in our clinic.

A) Number of CLD cases expressed as a percentage per year. B) Trend given in CLD expressed as a percentage per year. CLD, chronic liver disease; MASLD, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease; HCV, hepatitis C virus; ARLD, alcohol-related liver disease; AILD, autoimmune liver disease; HBV, hepatitis B virus.

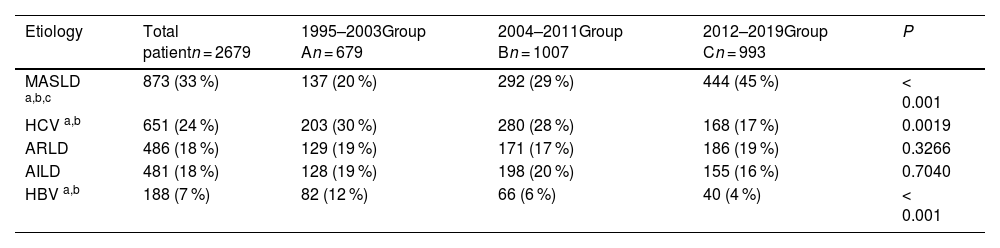

A statistically significant difference was found among the MASLD, HCV, and HBV groups, as determined by a one-way ANOVA. Tukey's post hoc analysis revealed a significant increase in the prevalence of MASLD, as well as a significant decrease in HBV and HCV over the three analyzed time periods. Among the five etiologies, HBV had the lowest percentage, while ARLD and AILD remained stable across the periods, showing no statistically significant differences. AILD were reported at similar frequencies across the three study periods, with no statistically significant differences. However, an absolute increase in the number of cases was observed during period B (Table 1).

Chronic liver disease in the three study periods.

| Etiology | Total patientn = 2679 | 1995–2003Group An = 679 | 2004–2011Group Bn = 1007 | 2012–2019Group Cn = 993 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MASLD a,b,c | 873 (33 %) | 137 (20 %) | 292 (29 %) | 444 (45 %) | < 0.001 |

| HCV a,b | 651 (24 %) | 203 (30 %) | 280 (28 %) | 168 (17 %) | 0.0019 |

| ARLD | 486 (18 %) | 129 (19 %) | 171 (17 %) | 186 (19 %) | 0.3266 |

| AILD | 481 (18 %) | 128 (19 %) | 198 (20 %) | 155 (16 %) | 0.7040 |

| HBV a,b | 188 (7 %) | 82 (12 %) | 66 (6 %) | 40 (4 %) | < 0.001 |

MASLD, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease; HCV, hepatitis C virus; ARLD, alcohol-related liver disease; AILD, autoimmune liver disease; HBV, hepatitis B virus. Values are n ( %). ap < 0.01, Group A vs Group B.

Overall, cirrhosis was present in 49 % of patients. At the time of admission, 36 % of patients had cirrhosis in 1995; however, this percentage progressively increased, reaching 67 % in 2019. ARLD and AILD had the highest proportion of cirrhosis (80 % and 49 %, respectively), while HBV had the lowest percentage. The analysis of cirrhosis prevalence by gender showed a higher prevalence in men for ARLD (91 %) and HBV (77 %), while women were predominant in AILD (82 %), HCV (57 %), and MASLD (56 %) (Table 2).

Comparison of the total number of patients and cases with cirrhosis.

*Mean and standard deviation, IQR, interquartile range, MASLD, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis; HCV, hepatitis C virus; ARLD, alcohol-related liver disease; AILD, autoimmune liver disease; HBV, hepatitis B virus.

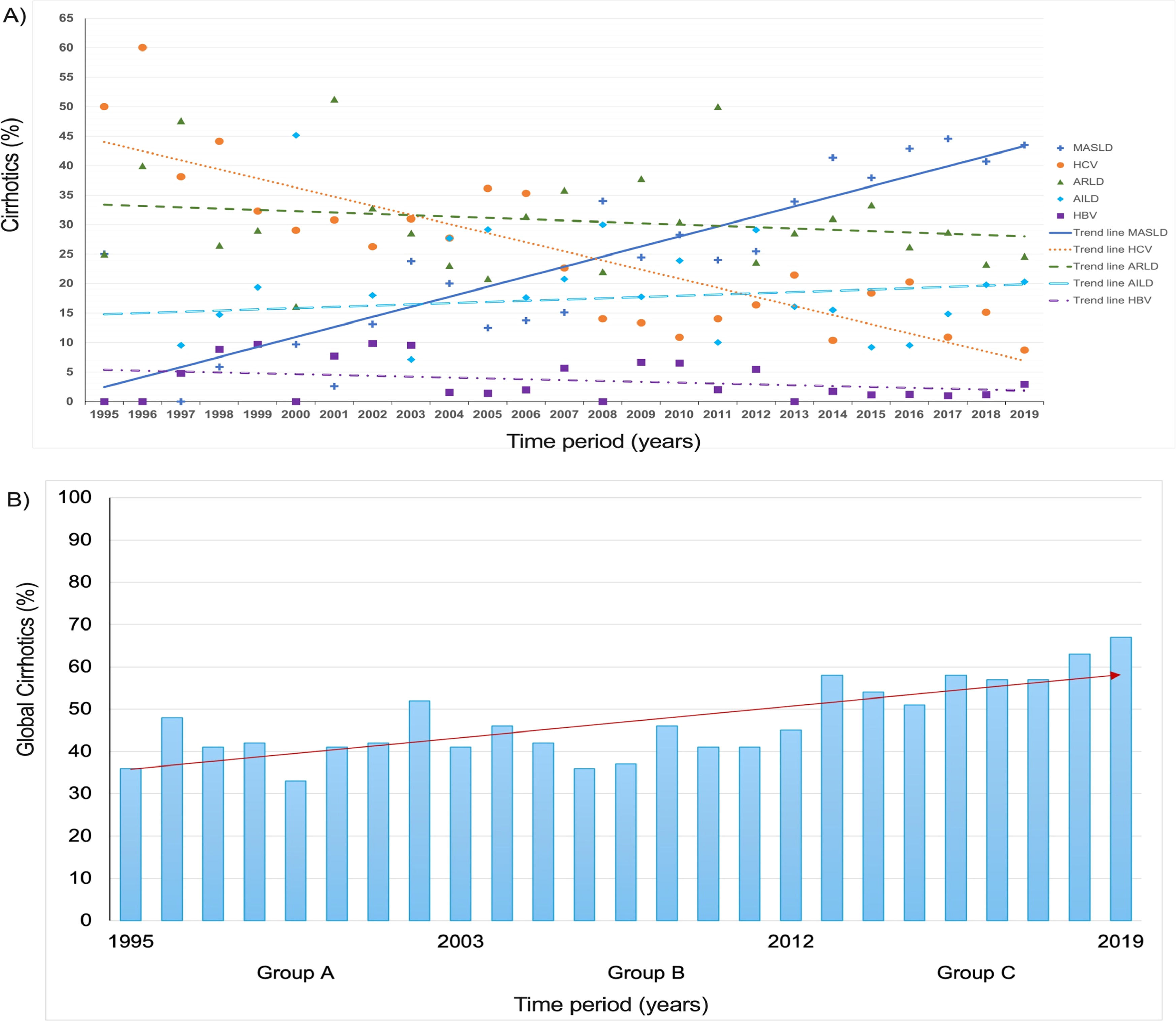

The analysis of cirrhosis trends across different etiologies over 25 years showed that MASLD moved from the fourth position in 2005 to the first in 2012, followed by ARLD and AILD (Fig. 2a). Additionally, a global increasing trend in cirrhosis prevalence was observed during the evaluated period (Fig. 2b).

A) Cirrhotic cases expressed as a percentage per year. B) Trend of cirrhosis in CLD in groups A, B, and C over 25 years. MASLD, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease; HCV, hepatitis C virus; ARLD, alcohol-related liver disease; AILD, autoimmune liver disease; HBV, hepatitis B virus.

This is the first long-term situational panorama study of CLD in a single center in Mexico. The results allowed us to identify variations in the presentation of different etiologies of CLD. During the study period from 1995 to 2019, a total of 2679 patients met the inclusion criteria, with a median age of 52 years, which is higher than the median age of 29 years reported by INEGI for the population of northeastern Mexico during the 1995–2020 period [30]. When considering obesity as a relevant risk factor across the entire cohort, it was observed that 72 % of the patients had a BMI greater than 25 Kg/m2. This finding is consistent with data reported by Mexican Clinical Practice Guidelines for Adult Overweight and Obesity Management, which indicate that approximately 75 % of the adult population in Mexico is overweight and obese [31]. On the one hand, the main contribution was to document how the frequency of metabolic CLD (i.e., MASLD) was increasing while national statistics documented the increase in MetS and its components, such as overweight, obesity, dyslipidemia, and T2DM [12]. On the other hand, the increased incidence of cirrhosis in our center paralleled the national statistics in this compilation alongside the presence of comorbidities that allow the development of MASLD and its complications as cirrhosis.

This study was conducted at a referral center for liver diseases in northeast Mexico, where MASLD was found to be the most frequent etiology among the five evaluated (33 %). This may explain why our reported prevalence is higher compared to the 23 % reported in previous studies on the Mexican population [32,33]. Additionally, it has been reported that the overall prevalence of obesity in patients with MASLD is 82 % [13]. A recent study conducted in five hospitals in central Mexico by González-Chagolla et al. found that MASLD progressed from being the third most common cause of cirrhosis in 2000 to the leading cause in 2012, accounting for 36 % of cirrhosis cases in 2019 [22]. These findings are comparable to those of our study in a single center in northeastern Mexico, where MASLD accounted for 33 % of the evaluated cases, establishing it as the leading cause of cirrhosis.

In relation to HCV, the present study found that in Group A (1995–2003), hepatitis C was the most frequent CLD, with a rate of 30 %. This may be attributed to the fact that, during that period, the only available treatment was pegylated interferon, which had a response rate of <50 % [34]. On the other hand, the frequency of HCV progressively decreased between Group B (2004–2011) and Group C (2012–2019), dropping from 28 % to 17 %, respectively. This reduction could be explained by the introduction of direct-acting antivirals (DAAs), which provide more effective treatments with fewer side effects. In Mexico, the public healthcare system incorporated DAAs in 2017, allowing more patients to access these therapies [35]. The decline observed between Groups B and C appears to be directly related to improved access to and effectiveness of DAAs treatment.

The prevalence of AILD in Mexico has been poorly reported, with estimates ranging from 7 % to 17 % of cirrhosis cases in the context of CLD [32,33]. In the present study, the prevalence of AILD remained relatively stable across the three time periods analyzed, although a slight decrease was observed in the most recent period (16 %). However, in the overall analysis, this etiology accounted for 18 % of cases, a proportion similar to that of alcohol-related liver disease (ARLD). This trend may be associated with the more specialized diagnostic approach employed at the referral center where the study was conducted.

In Mexico, although alcohol consumption has increased in recent years, mortality associated with alcohol-related liver disease (ARLD) has shown a declining trend [11]. It is estimated that only 10 % to 20 % of heavy chronic drinkers develop alcoholic hepatitis or cirrhosis [36].In our study, alcohol consumption in the northern population of the country remained consistently high over time, with no significant variation between the periods analyzed. Regarding cirrhosis related to ARLD, 14 % of patients had already developed the disease at their first consultation, accounting for 80 % of all diagnosed ARLD cases (387 out of 486 cases).Yeverino et al. reported that men represent the population most affected by alcoholism in Mexico [11], a finding that aligns with our results, in which 91 % of ARLD cases occurred in male patients.

In Mexico, the incidence of hepatitis B (HBV) was 0.63 cases per 100,000 inhabitants in 2019 [37,38]. Although the vaccine was introduced in 1984, it was incorporated into the national immunization schedule in 1999 [39], which was the year with the highest frequency of HBV-related consultations (18 %). Estimated vaccination coverage in 2018–2019 reached 55 % [40], which may have contributed to the observed reduction in HBV-related chronic liver disease. In this study, the frequency of HBV was 12 % during Period A and declined significantly in Periods B and C (p < 0.001), reaching only 4 % in the latter. At diagnosis, 23 % of patients already had cirrhosis, consistent with reports indicating that 15–40 % of chronic HBV infections progress to cirrhosis [41]. Initially, treatment involved interferon [42,43]; later, oral antivirals such as adefovir, entecavir (Baraclude), tenofovir, and more recently, tenofovir alafenamide were introduced [44]. These newer agents, with antifibrotic effects, may have improved patient outcomes, as previously reported by Tang et al. [41].

Cirrhosis is a key factor in the development of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). In Mexico, cirrhosis-related mortality increased from 27 to 34 per 100,000 inhabitants [45], and HCC is the third leading cause of death among individuals over 60 years old, with high mortality rates in rural areas [46]. Although this study did not include HCC cases, the incidence of cirrhosis in chronic liver disease (CLD) doubled between 1995 and 2019. Studies from northeastern Mexico highlight sex-related differences in etiology [46,47], identifying alcohol consumption (34.8 %) and MASLD (28.3 %) as the main causes of HCC [46–48], reflecting the growing impact of obesity.

The significant increase in cases of liver cirrhosis in Mexico is a concerning phenomenon that can be attributed to multiple interrelated factors. Traditionally, excessive alcohol consumption has been one of the main causes of cirrhosis in the country. However, in recent decades, another factor of equal or even greater relevance has emerged: the rise in metabolic diseases associated with the modern lifestyle.

Moreover, social, economic, and educational inequalities persist, making it difficult to adopt healthy habits and thus perpetuating this problem. The lack of effective public policies targeting nutrition, physical inactivity, and alcohol consumption has also contributed to this public health crisis.

5ConclusionsIn conclusion, this is the first long-term study of the situational panorama of CLD in a single center in Mexico, which allowed us to identify variations in the presentation of different etiologies of CLD, such as how the frequency of MASLD has increased while national statistics documented the increase in MetS and its components. The results demonstrate the trend toward an increased percentage of MASLD. A tendency to remain stable of ARLD and AILD was observed over the years, while the frequency of HCV declined in the third study period from 2012 to 2019, in the period when the DAAs were approved. A decline in the incidence of HBV from 1995 to 2019 was paralleled by the introduction of nucleoside(tide) analogs. The incidence of cirrhosis in CLD doubled during the 25 years of the study period, while MASLD showed the highest incidence of cirrhosis among the etiologies.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author contributionsL.E.M.-E, P.C.-P, L.T.-G: Conceptualization, data curation, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources, supervision, visualization, formal analysis, software, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing; S.R.-L, A.R.-C; C.T.-G: data curation, investigation, methodology, software, visualization, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing; I.G.L.-R, L.M.B.-C, I.E.H.-P: methodology, investigation, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing; J.R.Z.-N: validation, resources, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

None.

We thank Jorge Martín Llaca Díaz, MPH, for the epidemiological review of this study.