Food allergy is an increasing problem in public health, especially in childhood. Its incidence has increased in the last decade. Despite this, estimates of the actual incidence and prevalence are uncertain. The aim of this study was to estimate the prevalence of food allergy in infants and pre-schoolers.

MethodsThe parents of 3897 children completed questionnaires on the occurrence of any reaction to food. Children with parentally reported reactions were selected for further examination including a clinical interview, physical examination, allergic tests, and if necessary, oral food challenge to conclude the diagnosis of FA.

ResultsThe estimated prevalence of allergy in children aged 4–59 months was 0.61%, being, 1.9% in infants and 0.4% in pre-schoolers. Among the 604 patients physicians evaluated with parent-reported FA, 24 (4%) had a confirmed diagnosis of food allergy, and 580 (96%) were excluded in the remaining. Of these, approximately half (51/52.6%) of 97 infants and (128/48%) of 487 pre-schoolers already performed the diet exclusion suspected food for a period of time.

ConclusionThis study shows that high overall prevalence of parental belief of current food allergy however the same was not observed in the in physician-diagnosed food allergy. The prevalence of food allergy was lower than that observed in the literature. This study alerts health professionals to the risk entailed by overestimation of cases of food allergy and unnecessary dietary exclusion, which may result in impairment in growth and development of children, especially in their first years of life.

Food allergy (FA) is an adverse immune response that occurs reproducibly on exposure to a given food.1,2 FA may be classified according to the immunological mechanism involved: IgE-mediated in which the reaction generally occurs in the first two hours after food exposure and is mediated by Immunoglobulin E (IgE); non IgE-mediated with symptoms that usually occur hours or days after food exposure and is associated with a cellular response; and mixed that involves both mechanisms.3,4

The clinical manifestations differ based on the immune mechanism involved. IgE-mediated reactions could present skin reactions (atopic dermatitis, urticaria, angio-oedema), gastrointestinal (swelling and itching of the lips, tongue, vomiting and diarrhoea), respiratory (dyspnoea, rhinorrhoea) and systemic reactions (anaphylaxis). Non-IgE mediated reactions present mainly gastrointestinal symptoms as proctocolitis, enterocolitis, and enteropathy. Mixed reactions are implicated as manifestations of atopic dermatitis, eosinophilic oesophagitis, and eosinophilic gastroenteritis.3,4

FA has been associated with an impaired quality of life, psychosocial impact in children and their families resulting in limited social interactions, a heightened risk of severe allergic reactions and potential fatality, and high socioeconomic cost.2,5,6 FA is an increasing problem in public health, especially in childhood.2,7

Despite the suggested increasing frequency of FA, estimates of the actual incidence and prevalence are uncertain.2,7,8 Most studies have either focused on specific populations or only on selected food allergens and relatively few epidemiological studies have used the gold standard of diagnosis – the double-blind, placebo-controlled food challenge in defining FA. Most frequency estimates have been based on lay perceptions or specific IgE or skin prick test (SPT) sensitisation to common food allergens. Both self-perception and allergic sensitisation are known to substantially overestimate the actual frequency of FA.7–9

The latest three systematic reviews of reported frequency of FA estimates the prevalence of self-reported FA to range from 3 to 35% and confirmed FA range from 6% to 8% of the population.1,3,6,8,10 A recent systematic review estimated reported prevalence of allergy to common food in Europe around 6% for cow's milk, 2.5% for egg, and 3.5% for wheat, while confirmation by oral food challenges reduced this to 0.6%, 0.2%, and 0.1% for the same foods. Allergy to cow's milk and egg was more common among younger children, and to peanut, tree nuts, fish, and shellfish was more common among the older ones. There were insufficient data to compare the estimates of soy and wheat allergy between the age groups.8

However, the prevalence of FA in Brazil is unknown. The objective of this study is to evaluate the prevalence and clinical characteristics of FA in infants and preschool children from Uberlândia, Brazil.

MethodsPopulation descriptionThis study constitutes the second phase of research project entitled “Prevalence of food allergy in infants and preschoolers from Uberlândia”. This cross-sectional study was conducted during the period from March 2012 to September 2013 and enrolled all children aged 4–59 months in the Public School District for Early Childhood Education. Uberlândia is located in Minas Gerais State, the estimated population in 2015 is 662,362 inhabitants, the human development index reached 0.789 in 2010, the climate is classified as tropical savannah but experiences a mild temperature (annual mean: 22°C) since it is located at 850m altitude11.

The data from the first phase was previously published and describe the parent reported food allergy in these participants.12 The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Uberlândia. All parents were informed about the study and signed consents were obtained.

Study designIn the first phase, a validated self-administered questionnaire for FA screening was used to collect the data.13 The questionnaires were delivered to the parents of children in all district municipal public schools and after appropriate filling; they were returned to the school office, where they were evaluated by the researchers. The data collected was about presence of atopy (history of rhinitis, atopic dermatitis and asthma), parent-reported food allergy and allergic symptoms related to food including the type of food and the symptoms experienced that had occurred.

In the second phase, all children whose parents responded positively to the question about the perception of presence of any food allergies were invited for further study, including a clinical interview, physical examination, allergic tests, and if necessary, an oral food challenge to conclude the diagnosis of FA. Patients with regular ingestion of implicated foods without symptoms were considered as non-allergic.

The diagnosis of food allergy was considered in three situations. (1) Patients with a recent history of urticaria, angio-oedema, or anaphylaxis occurred less than two hours after ingestion of suspected food plus a positive skin prick test; (2) Patients with a history of urticaria, angio-oedema, or anaphylaxis occurred less than two hours after ingestion of suspected food that maintain the diet exclusion of suspected food plus a positive oral food challenge; or (3) Patients with diagnosis of atopic dermatitis or enterocolitis that improve clinically after exclusion and present a worsening after the introduction of the suspected food.

Prick-to-prick skin testThe prick-to-prick skin test (SPT) with fresh foods was performed in children with history or symptoms suggestive of IgE mediated reaction. This test was performed in duplicate with a lancet with 1mm tip on the volar surface of the forearm according to European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI) guidelines.14 The suspected allergens foods were employed. Histamine dihydrochloride (10mg/dl) and diluent served as a positive and negative control, respectively. Skin responses were measured 15min later, considering a wheal diameter of ≥3mm or larger as a positive skin reaction to the diluent.15,16

The SPT is considered the main method to confirm IgE mediated allergic sensitisation. It is a minimally invasive procedure, fast, easy to perform, and reproducible. SPT has a positive predictive value (PPV) of only 50% and a high negative predictive value (95%), therefore, they are rarely negative in IgE-mediated reactions.17

Oral food challengesAll children with suspected allergy (no recent history in the previous six months of allergy IgE-mediated and non-IgE mediated history) were submitted to oral food challenges (OFC). Patients with a recent convincing history (previous six months) of IgE-mediated allergy (urticaria, angio-oedema and anaphylaxis) with positive SPT were dispensed of OFC.14

The challenges were performing according to EAACI guidelines14 by trained staff under hospital with emergency support. A single-blind challenge was performed because all patients of the study were younger than five years old. All patients were examined prior to and during the challenge for the presence of any allergic reaction by three experienced paediatric allergists. The development of one or more of the following objective criteria was used to define a positive OFC: persisting itching, non-contact urticaria persisting for at least five minutes, angio-oedema, eczema exacerbation, rhinoconjunctivitis, vomiting, and circulatory or respiratory compromise. A paediatric allergy specialist scored the symptoms.18 The challenge was terminated when objective symptoms were noted by the physician or when the infants were observed for a minimum of 4h in the hospital without symptoms.

For late responses, the family was oriented to offer the implicated food daily and observe the possible signs and symptoms. After seven days, the researchers telephoned to inquire about these symptoms and signs in the period. If there were no symptoms, the OFC were considered negative. If there was any alteration, the patients were re-examined by the medical team.14

The OFC procedure was modified from other studies and started with 2ml of CM (or soy milk, given the case), which was then increased in volume every 15min (followed by 10, 20, 30, 40ml) until the final dose of 100ml was ingested. To perform OFC to baked egg and wheat was evaluated using the OFC consumption cake baked for 40min at a temperature of 200°C in an industrial furnace and fed at increasing portions (10, 20, 30 and 40g) to the child. To verify allergy to raw eggs, were used in OFC beaten egg white with sugar.19–21

Statistical analysisThe Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to determine whether variables were normally distributed. For continuous variables, groups were compared using the Mann–Whitney test. The Fisher exact test and Chi-square were used for categorical variables. The level of significance for all statistical tests was 2-sided, P<0.05. All analyses were conducted using Graph Pad Prism 5.0 (La Jolla, CA, USA).

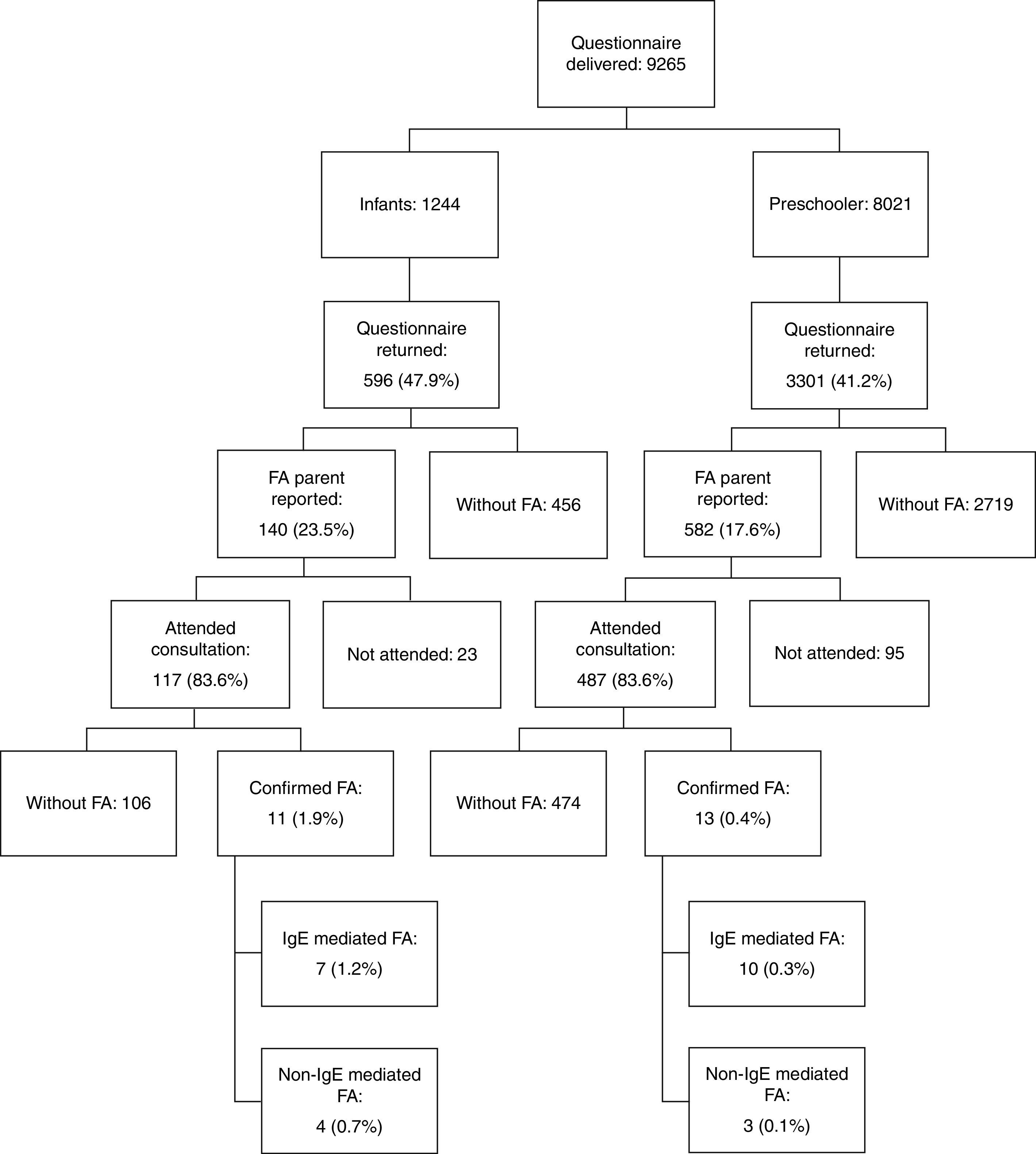

ResultsThe questionnaire was delivered to 9265 children; Fig. 1 shows the flowchart for our study selection and screening. The prevalence of parent-reported food allergy was 23.5% in infants and 17.6% in pre-schoolers. The frequency of parental history of allergies, other types of allergies in the patients, food allergens and clinical manifestations reported by the families has been published previously.12

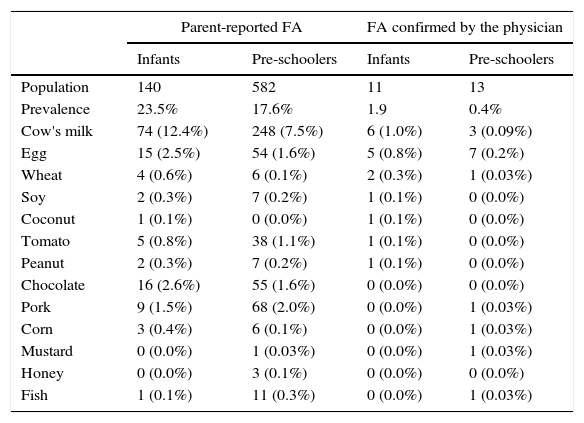

Six hundred and four children of 722 whose parents reported food allergy attended medical consultation. After the consultation, allergic evaluation, and OFC, 24 (0.61%) of children who had returned the initial questionnaire (3897 participants) had a final diagnosis of food allergy. Of these, 11 (1.9%) were aged 4–23 months and 13 (0.4%) 24–59 months (Table 1).

Prevalence of food allergy reported by parents and confirmed by the physician in children aged 4–59 months enrolled in School District for Early Childhood Education.

| Parent-reported FA | FA confirmed by the physician | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infants | Pre-schoolers | Infants | Pre-schoolers | |

| Population | 140 | 582 | 11 | 13 |

| Prevalence | 23.5% | 17.6% | 1.9 | 0.4% |

| Cow's milk | 74 (12.4%) | 248 (7.5%) | 6 (1.0%) | 3 (0.09%) |

| Egg | 15 (2.5%) | 54 (1.6%) | 5 (0.8%) | 7 (0.2%) |

| Wheat | 4 (0.6%) | 6 (0.1%) | 2 (0.3%) | 1 (0.03%) |

| Soy | 2 (0.3%) | 7 (0.2%) | 1 (0.1%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Coconut | 1 (0.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.1%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Tomato | 5 (0.8%) | 38 (1.1%) | 1 (0.1%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Peanut | 2 (0.3%) | 7 (0.2%) | 1 (0.1%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Chocolate | 16 (2.6%) | 55 (1.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Pork | 9 (1.5%) | 68 (2.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.03%) |

| Corn | 3 (0.4%) | 6 (0.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.03%) |

| Mustard | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.03%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.03%) |

| Honey | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (0.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Fish | 1 (0.1%) | 11 (0.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.03%) |

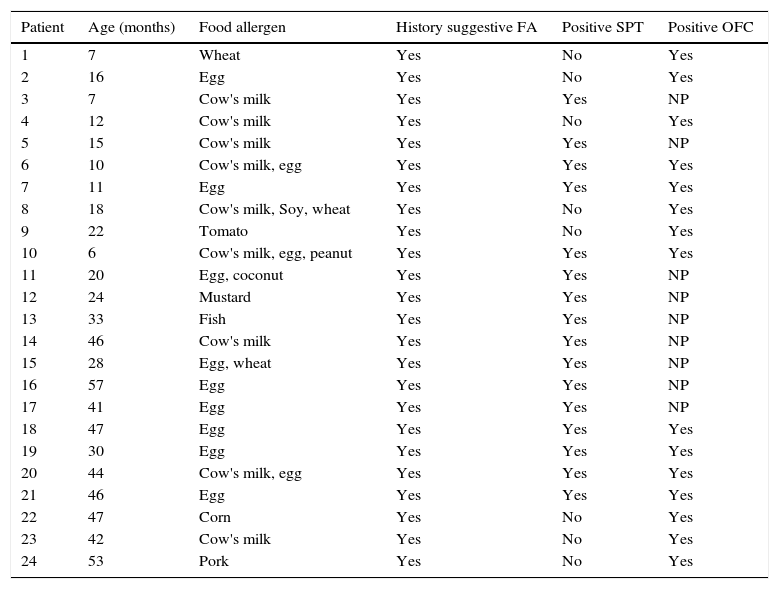

The details of diagnosis of food allergy in patients are shown in Table 2. In the present study, 46 open oral food challenges were performed in 40 patients, of whom 15 (37.5%) showed a positive clinical reaction to at least one challenge. The food allergen responsible for the largest number of positive food challenge was egg in eight (53.3%), followed by CM in six (40.0%), wheat in two (13.3%), soybean, corn, tomato, coconut, pork and peanut one (6.6%). The presence of one food allergen involved was more frequent in infants and pre-schoolers (63.6%/76.9%).

Distribution of patients with food allergy diagnosed by the physician in infants and pre-schoolers enrolled in School District for Early Childhood Education.

| Patient | Age (months) | Food allergen | History suggestive FA | Positive SPT | Positive OFC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 7 | Wheat | Yes | No | Yes |

| 2 | 16 | Egg | Yes | No | Yes |

| 3 | 7 | Cow's milk | Yes | Yes | NP |

| 4 | 12 | Cow's milk | Yes | No | Yes |

| 5 | 15 | Cow's milk | Yes | Yes | NP |

| 6 | 10 | Cow's milk, egg | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 7 | 11 | Egg | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 8 | 18 | Cow's milk, Soy, wheat | Yes | No | Yes |

| 9 | 22 | Tomato | Yes | No | Yes |

| 10 | 6 | Cow's milk, egg, peanut | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 11 | 20 | Egg, coconut | Yes | Yes | NP |

| 12 | 24 | Mustard | Yes | Yes | NP |

| 13 | 33 | Fish | Yes | Yes | NP |

| 14 | 46 | Cow's milk | Yes | Yes | NP |

| 15 | 28 | Egg, wheat | Yes | Yes | NP |

| 16 | 57 | Egg | Yes | Yes | NP |

| 17 | 41 | Egg | Yes | Yes | NP |

| 18 | 47 | Egg | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 19 | 30 | Egg | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 20 | 44 | Cow's milk, egg | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 21 | 46 | Egg | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 22 | 47 | Corn | Yes | No | Yes |

| 23 | 42 | Cow's milk | Yes | No | Yes |

| 24 | 53 | Pork | Yes | No | Yes |

NP, not performed.

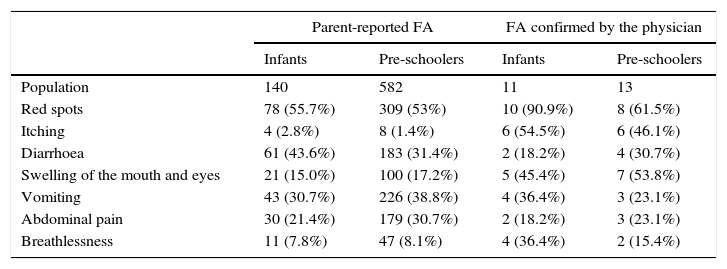

Reactions (swelling of the mouth and eyes, itchy eyes and skin, spots and patches on the skin), were the most common (100%), followed by respiratory (cough, stuffy nose, shortness of breath and itch throat) with 45.4% in infants and 46.1% in pre-schoolers and gastrointestinal reactions (diarrhoea, vomiting, abdominal pain) with 36.3% in infants and 46.1% in pre-schoolers. The most common clinical manifestations can be seen in Table 3. In 17 individuals with IgE-mediated confirmed food allergy the main signs and symptoms were red spots in 13 (76.4%), swelling in the mouth and/or eyes in 12 (70.5%), itching in 11 (64.7%), dyspnoea in five (29.4%), vomiting in five (29.4%), diarrhoea in five (29.4%), and abdominal pain in four (23.5%). In seven participants with non-IgE-mediated confirmed FA, six (85.7%) presented a worsening of atopic dermatitis lesions, vomiting in two (28.5%), diarrhoea in one (14.3%), and abdominal pain in one (14.3%). Atopic dermatitis was identified in seven (29.1%) of 24 total confirmed FA patients.

Distribution of the most prevalent clinical manifestations in food allergy reported by parents and confirmed by the physician in infants and pre-schoolers.

| Parent-reported FA | FA confirmed by the physician | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infants | Pre-schoolers | Infants | Pre-schoolers | |

| Population | 140 | 582 | 11 | 13 |

| Red spots | 78 (55.7%) | 309 (53%) | 10 (90.9%) | 8 (61.5%) |

| Itching | 4 (2.8%) | 8 (1.4%) | 6 (54.5%) | 6 (46.1%) |

| Diarrhoea | 61 (43.6%) | 183 (31.4%) | 2 (18.2%) | 4 (30.7%) |

| Swelling of the mouth and eyes | 21 (15.0%) | 100 (17.2%) | 5 (45.4%) | 7 (53.8%) |

| Vomiting | 43 (30.7%) | 226 (38.8%) | 4 (36.4%) | 3 (23.1%) |

| Abdominal pain | 30 (21.4%) | 179 (30.7%) | 2 (18.2%) | 3 (23.1%) |

| Breathlessness | 11 (7.8%) | 47 (8.1%) | 4 (36.4%) | 2 (15.4%) |

Among the 604 patients with parent-reported FA evaluated by physicians in our unit, 24 (4%) had a confirmed diagnosis of food allergy, while the diagnosis of food allergy was excluded in the remaining 580 (96%). Of these, approximately half (51/52.6%) of 97 infants and 154 (31.6%) of 487 pre-schoolers already performed the diet exclusion of the suspected food for a period of time.

The most frequent food allergens excluded unnecessarily in infants/pre-schoolers were milk (51%/45.3%), chocolate (15.7%/8.5%), fruit (13.7%/4.6%), egg (5.9%/3.9%), pork (5.9%/14.8%) and fish (5.9%/3.1%)

DiscussionThe incidence and prevalence of FA have changed over time, and many studies have indeed suggested a true rise in prevalence over the past 10–20 years. Studies of FA incidence, prevalence, and natural history are difficult to compare because of inconsistencies and deficiencies in study design and variations in the definition of FA.8,9

The majority of the FA prevalence studies were done based on self- reported or parental-reported questionnaires, this methodology used for populational studies is subjective and causes an overestimation in the FA prevalence. A recent systematic review of European studies relates that the point prevalence of self-reported food allergy was approximately six times higher than the point prevalence of challenge- proven food allergy. Our results showed the confirmation by clinical history, allergic tests, and OFC in only 4% (24/604) of children whose parents reported food allergy; in other words, a parental FA reported 25 times higher than confirmed FA diagnosis. This discrepancy occurred probably via an inadequate diagnosis of food allergy done based only in dosage of specific IgE by general practitioner, or by a confusion of food allergy symptoms with other children problems by parents.15,22The prevalence of cow's milk protein food allergy in the present study was 1.0% in infants and 0.09% of pre-schoolers. These values agree with meta-analysis studies that related a prevalence of CM allergy after OFC of 0.6% of infants. On the other hand, these data are lower than some cohort studies that found prevalence of CM allergy to vary from 1.7 to 2.4% in infants.22,23 The difference between cohort and transversal studies occurs because a number of patients with a diagnosis of CM allergy improved their allergy with growing, i.e., cohort studies calculate all infants with allergy during the first years while transversal studies count only the positives in the moment of the OFC or tests. In our study, infants with a medical approach and a convincing history of CM allergy but with no more allergies in the moment of evaluation were approximately 1.5% of infants (data not shown), which adds 1.0% more to actual CM allergy, reaching 2.5%, a similar prevalence to cohort studies.

The prevalence of hen's egg food allergy confirmed by physician was 0.8% in infants and 0.2% in pre-schoolers, responsible for 50% of FA reactions. This is similar to other studies reporting the prevalence in recent meta-analysis performed in Europe when the prevalence after OFC was 0.2% and lower than a study showing that estimated point prevalence of allergy to egg in children aged 2 1/2 years was 1.6%, with an upper estimate of the cumulative incidence by this age calculated roughly at 2.6%. In a recent Australian study, the prevalence of hen's egg allergy was 9%, higher than found in the majority of studies.9,24,25

The prevalence of other food allergies was low, including peanuts, wheat, soy, and corn, and this coincides with other studies confirmation of FA. The symptoms presented by patients are similar to those described previously.

The overestimation of cases of FA serves as a warning to all health professionals regarding the need for a careful evaluation in the diagnosis of FA and correct dietary exclusion, in order to avoid damaging growth and development posed by the restriction of essential foods with a high protein, vitamin and mineral content such as milk, egg, meat and fruit. It is noteworthy that inadequate diagnosis of food allergy leads to unnecessary restriction diets and impairment of the child's nutritional status. These data agree with several studies have been published warning of the risk of parental perceived FA leading to severe exclusion diet with nutritional consequences, including failure to thrive especially because most children develop FA within the first two years of life, which is a crucial period of growth and development.1,26,27

The present study has some limitations, including its cross-sectional format and the selected target population. The infants and pre-schoolers evaluated in the study were in the Public School District for Early Childhood Education, and clinical practice teaches us that many parents of infants with food allergy delay the admission of their children in the school for fear of diet transgressions that occur in these locations, and this situation could reduce the real number of patients with FA diagnosis. The cross-sectional format considers only the patients diagnosed at the moment of the research and excludes patients that could have a previous real food allergy. Another limitation is related to adjusting for non-response, even though the study presents a high response rate, without adjusting the researchers assume the same rate between the responder and non-responder population and could cause an overestimation of food allergy frequency, as previous described.28

ConclusionsThe prevalence of food allergy is lower than that found in the majority of literature suggesting an overestimation of cases and the need for more populational studies with confirmation of FA.

The main foods are part of the usual diet in our environment, such as milk, egg, wheat, soy, coconut, tomato, peanut, mustard. Although numerous studies suggest that food allergens suffer regional and cultural influences, in this study it was the same as described in the literature.

The knowledge and demystification of food allergy is important for families and general practitioners, avoiding the unnecessary exclusion of foods that can lead to the injury in the growth and development of children, especially in their first years of life.

Ethical disclosuresConfidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data and that all the patients included in the study have received sufficient information and have given their informed consent in writing to participate in that study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects mentioned in the article. The author for correspondence is in possession of this document.

Protection of human subjects and animals in researchThe authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the responsible Clinical Research Ethics Committee and in accordance with those of the World Medical Association and the Helsinki Declaration.

FundingThe authors declare that there is no financial support regarding the publication of this paper.

Author contributionLuciana Carneiro Pereira Gonçalves, RD, contributed with conception and design of the study, data collection, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the article, revising it critically for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be submitted.

Tássia Cecília Pereira Guimarães, MN, contributed with conception and design of the study, data collection, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the article, revising it critically for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be submitted.

Raissa Martins Silva, MD, contributed with conception and design of the study and data collection, generation, analysis and interpretation of the data.

Marina Fernandes Almeida Cheik, MD, contributed with conception and design of the study and data collection, generation, analysis and interpretation of the data.

Ana Carolina Ramos de Nápolis, MD, contributed with conception and design of the study and data collection, generation, analysis and interpretation of the data.

Gisele Barbosa e Silva, MD, contributed with conception and design of the study and data collection, generation, analysis and interpretation of the data.

Gesmar Rodrigues Silva Segundo, MD, PhD, contributed with conception and design of the study, data collection, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the article, revising it critically for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be submitted.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper.