There is a conflictive position if some foods and Mediterranean diet (MedDiet) consumed by the mother during pregnancy and by the child during the first years of life can be protective for current wheezing, rhinitis and dermatitis at preschool age.

MethodsQuestionnaires of epidemiological factors and food intake by the mother during pregnancy and later by the child were filled in by parents in two surveys at two different time points (1.5 yrs and 4 yrs of life) in 1000 preschoolers.

ResultsThe prevalences of current wheezing, rhinitis and dermatitis were 18.8%, 10.4%, and 17.2%, respectively. After multiple logistic analysis children who were low fruit consumers (never/occasionally) and high fast-food consumers (≥3 times/week) had a higher risk for current wheezing; while intermediate consumption of meat (1 or 2 times/week) and low of pasta by mothers in pregnancy were protected. For current rhinitis, low fruit consumer children were at higher risk; while those consuming meat <3 times/week were protected. For current dermatitis, high fast food consumption by mothers in pregnancy; and low or high consumption of fruit, and high of potatoes in children were associated to higher prevalence. Children consuming fast food >1 times/week were protected for dermatitis. MedDiet adherence by mother and child did not remain a protective factor for any outcome.

ConclusionLow consumption of fruits and high of meat by the child, and high consumption of potatoes and pasta by the mother had a negative effect on wheezing, rhinitis or dermatitis; while fast food consumption was inconsistent.

It is well recognised that most allergic manifestations, e.g. asthma, rhinitis and dermatitis, usually appear during preschool age.1 Perinatal life is a critical period of the immune system development, and maternal diet during pregnancy has been proposed to influence foetal immune responses that might predispose to childhood allergic manifestations.2 Decreasing the intake of antioxidants (fruit and vegetables), increasing that of n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) (in margarine or vegetable oil), and decreasing that of n-3 PUFA (oily fish) could have contributed to the recent increase in asthma and atopic diseases. Thus the role of diet during foetal (programming) and in early life (preschool) ages is an area for intense research.3

We previously showed that adherence to the Mediterranean diet [MedDiet] (in the univariate analysis) and to olive oil consumption (also after multivariate analysis) during pregnancy were protective factors for recurrent wheezing during the first year of life in Spanish infants.4 Another study from Spain and Greece showed that high meat intake and processed meat intake during pregnancy were associated with an increased risk of wheeze in the first year of life; whilst a high intake of dairy products, but not MedDiet, was significantly associated with a decreased risk of infant wheeze.5 However, a recent meta-analysis performed exclusively on maternal nutrition during pregnancy showed that MedDiet and higher maternal intake of vitamins D and E, zinc, copper, magnesium and vegetables during pregnancy are associated with a lower risk of wheeze and atopic diseases in childhood.6

On the other hand, we also reported previously that MedDiet adherence during preschool age was an independent protective factor for current wheezing in preschoolers, regardless of obesity and physical activity7; and for current severe asthma among girls at school-age (regardless of physical activity).8 Furthermore, a meta-analysis on adherence to MedDiet in children showed a trend that this type of diet is associated with lower occurrence of current wheeze, current severe wheeze, or asthma ever. For current and current severe wheeze, the significance of the association was mainly driven by the results in Mediterranean populations.9

However, few studies have looked into the interaction between maternal diet, especially MedDiet consumed by the mother during pregnancy and by the offspring during preschool age, on asthma, dermatitis and rhinitis in the offspring. The objective of the present study was to investigate if MedDiet adherence by the mother during pregnancy and by the child had an influence on asthma, rhinitis or dermatitis in the offspring during preschool age. We hypothesised that MedDiet consumed by the mother and by the child is a protective factor for asthma and allergic disease.

MethodsPopulationThis longitudinal prospective study started as a part of the International Study of Wheezing in Infants (EISL) study performed in Cartagena, Spain. Children have been followed up afterwards.10 Briefly, all primary care health centres monitoring children for nutrition, growth and development, and/or for vaccine administration from the health program in Cartagena were included as recruiting centres; and when the child attended to receive vaccination at 15 or 18 months of age (“survey 1.5”), parents or guardians were asked to complete the questionnaire, emphasising on nutritional aspects of the mother during pregnancy and respiratory/allergy symptoms in the offspring which occurred during the first 12 months. At age four years (“survey 4”) the participant families were contacted again to answer a similar questionnaire, emphasising nutrition and respiratory/allergy symptoms occurred in the offspring during the previous 12 months.

QuestionnairesAt survey 1.5, a standardised and validated questionnaire,10 including questions on epidemiological risk/protective factors, was completed. The questions were: age; gender; race; type of delivery; number of siblings; birth weight and height (by parental report); low birth weight (<2000g or <2500g); exclusive breastfeeding for six months (without any formula feeding or infant food); air pollution (living near to factories or roads with heavy traffic); mould stains on the household walls; dogs and cats at home, during pregnancy and at present; maternal age and educational level; oral contraceptive used before pregnancy; paracetamol used during pregnancy; number of colds during the first year of life; maternal smoking during pregnancy; paternal current smoking; parental asthma, rhinitis and eczema.

At survey 4, the data collected included: kindergarten attendance; parental current tobacco smoking; dogs and cats at home; mould stains on the household walls; type of fuel used in heating and cooking systems; physical exercises (hours/week); TV-video play watching (hours/day); and height and weight (by parental report).

Definitions of outcome variablesCurrent wheezing was defined as a positive answer to the question: “Has your child had wheezing or whistling in the chest during the first 12 months of life?”. Current rhinitis was defined as a positive answer to the following question “Has your child had a problem with sneezing or a runny or blocked nose when he/she did not have a cold or the flu accompanied by itchy, watery eyes during the last 12 months?”. Current eczema was defined as a positive answer to the following question: “During the first 12 months of his/her life, has your child had an itchy rash which was coming and going in any part of his/her body except around the mouth and nose, and on the nappy area?”.

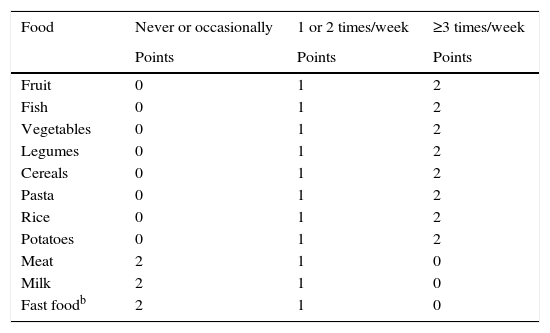

Questions were asked regarding the consumption of foods (never or occasionally, 1 or 2 times per week, and 3 or more times per week) by the mother during pregnancy at survey 1.5, and by the child at survey 4. The MedDiet score employed in the present study was previously developed by our group7,8 and is based on the score by Psaltopoulou et al.11: fruit, fish, vegetables, legumes, cereals, pasta, rice and potatoes are considered “pro- Mediterranean” foods and rated according to the frequency of their intake (0 points=never or occasionally, 1 point=1 or 2 times/week, or 2 points=≥3 times/week). Meat, milk and fast foods are considered “anti-Mediterranean” foods and are rated inversely (Table 1). We used MedDiet as quartiles of score and also as raw score. As in our three previous reports,4,7,8 olive oil was not included as part of the MedDiet score and was recorded apart. Therefore, a question about the type of oil used for cooking and dressing salads and vegetables was included; and a dichotomous variable: olive oil vs. others [margarine, butter or other oils] was built. Additionally, the frequency of industrial infant foods (e.g. yogurt, puddings, petit-suisse, commercial chips, jelly, chocolate, soft drinks and bottled/packed juices) consumed by the infants during their first year of life was recorded (as never, once per month, once per week and every day).

The Ethics Committee of the University of Murcia approved the study, and full informed and signed consent was obtained from parents before completing the questionnaire.

Statistical analysisThree different outcomes were considered: current wheezing, current rhinitis and current dermatitis at survey 4. The bivariate analysis was performed by means of the Fisher's exact test for categorical variables; the chi square test for trend for ordinal variables; and the Student t-test for independent samples for continuous variables. Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were also calculated. Multivariate logistic regression analysis models were built for each outcome. Adjusted OR (aOR) and 95% CI were calculated from the logistic regression models. Statistical analyses were performed using statistical software (SPSS® v.17, IBM, Armonk, NY, US).

ResultsDuring the study period 3564 children were registered born in the health district of Cartagena. After discarding those who were not of Spanish origin and those without correct contact data, 2396 families were invited to participate in the study, of whom 1694 completed survey 1.5 (70.7% participation rate). After excluding blank questionnaires or blank answers to the questions related to wheezing, rhinitis or dermatitis at survey 4, 1000 children had complete data for both surveys (1.5 and 4) and were analysed in the present report. The mean (SD) age was 16.9±2.7 months at survey 1.5 and 40.7±4.4 months at survey 4; 54.7% were males; and 98.2% had a complete immunisation schedule. At survey 4, the prevalence of current wheezing, rhinitis and dermatitis were respectively 18.8%, 10.4%, and 17.2%.

Current wheezing at survey 4In terms of demographic and anthropometric characteristics the statistically significant differences between children with and without current wheezing were: length at birth; birth weight; number of colds during the first year of life; maternal tobacco smoking at survey 1.5; paternal rhinitis; mould stains on the household at survey 4; and age of wheezing onset (Table 2).

Sociodemographic and anthropometric characteristics (% or mean±SD) of population (n=1000).

| Current wheezing | Current rhinitis | Current dermatitis | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | p value*** | Yes | No | p value*** | Yes | No | p value*** | |

| Age (yrs) | 40.16±4.02 | 40.78±4.47 | 0.082 | 41.36±4.25 | 40.59±4.41 | 0.092 | 40.88±4.63 | 40.63±4.35 | 0.495 |

| Gender (males) | 55.3 | 54.6 | 0.871 | 66.3 | 53.3 | 0.012 | 60.5 | 53.4 | 0.11 |

| Weight at birth (kg) | 4.09±0.82 | 4.19±0.67 | 0.09 | 4.25±0.64 | 4.16±0.71 | 0.22 | 4.25±0.68 | 4.16±0.71 | 0.15 |

| Length at birth (cm) | 49.29±3.02 | 49.86±2.72 | 0.014 | 49.77±2.74 | 49.75±2.79 | 0.927 | 50.05±2.58 | 49.68±2.83 | 0.114 |

| Delivery by C-section | 29.4 | 26.0 | 0.40 | 30.3 | 26.2 | 0.40 | 29.0 | 26.2 | 0.5 |

| Birth weight <2500g | 13.3 | 10.5 | 0.293 | 6.9 | 11.5 | 0.182 | 10.2 | 11.2 | 0.786 |

| Birth weight <2000g | 5.5 | 1.8 | 0.008 | 2.0 | 2.6 | 1.00 | 1.8 | 2.7 | 0.785 |

| Exclusive breastfeeding | 17.8 | 19.5 | 0.679 | 19.4 | 19.2 | 1.00 | 15.2 | 19.9 | 0.165 |

| Maternal age (yrs) | 32.58±5.27 | 32.16±5.07 | 0.318 | 32.23±5.79 | 32.24±5.03 | 0.986 | 32.28±4.66 | 32.24±5.2 | 0.917 |

| Maternal studies | 0.29 | 0.029 | 0.228 | ||||||

| Basic or none | 8.6 | 10.5 | 9.8 | 10.2 | 13.3 | 9.4 | |||

| High school incomplete | 8.1 | 12.4 | 10.8 | 11.6 | 8.4 | 12.2 | |||

| High school complete | 55.9 | 50.5 | 63.7 | 50.1 | 51.5 | 51.5 | |||

| University | 27.4 | 26.6 | 15.7 | 28.1 | 26.3 | 26.9 | |||

| Oral contraceptive used | 0.558 | 0.467 | 0.246 | ||||||

| Never | 56.5 | 61.2 | 68.2 | 59.4 | 56.4 | 61.1 | |||

| <1 yr | 14.9 | 11.4 | 8.0 | 12.5 | 16.8 | 11.1 | |||

| 1–3 yrs | 18.6 | 18.5 | 15.9 | 18.8 | 16.8 | 18.9 | |||

| 4–6 yrs | 9.9 | 9.0 | 8.0 | 9.3 | 10.1 | 9.0 | |||

| Siblings (n) | 0.78±0.88 | 0.74±0.99 | 0.646 | 0.59±0.72 | 0.77±1.0 | 0.09 | 0.68±0.78 | 0.76±1.0 | 0.323 |

| Paracetamol during preg | 0.946 | 0.265 | 0.021 | ||||||

| Never or <1/m | 82.6 | 83.4 | 79.2 | 83.7 | 85.4 | 82.6 | |||

| 1–4 times/m | 14.7 | 13.7 | 15.8 | 13.6 | 9.1 | 14.9 | |||

| >1time/week | 2.7 | 2.9 | 5.0 | 2.7 | 5.5 | 2.4 | |||

| Pets during pregnancy | 26.7 | 24.8 | 0.576 | 35.9 | 23.9 | 0.011 | 27.9 | 24.6 | 0.385 |

| Maternal smoking in preg | 24.9 | 18.7 | 0.038* | 22.1 | 19.6 | 0.518 | 22.2 | 19.4 | 0.40 |

| Mould stains at S1.5 | 16.8 | 13.6 | 0.292 | 21.4 | 13.3 | 0.023* | 17.0 | 13.6 | 0.277 |

| Pets at S1.5 | 31.0 | 29.9 | 0.791 | 39.8 | 29.0 | 0.031 | 35.5 | 29.1 | 0.059* |

| Day care at S1.5 | 9.7 | 13.1 | 0.22 | 16.5 | 12.0 | 0.206 | 13.5 | 12.2 | 0.612 |

| Type of fuel at S1.5 | 0.384 | 0.625 | 0.432 | ||||||

| Electricity/central gas | 96.3 | 94.5 | 97.8 | 94.5 | 92.9 | 95.2 | |||

| Gas stove | 1.2 | 3.4 | 1.1 | 3.2 | 3.9 | 2.8 | |||

| Kerosene/wood/charcoal | 2.5 | 2.2 | 1.1 | 2.1 | 3.2 | 2.0 | |||

| Colds during first yr. life | 5.66±8.44 | 4.02±5.11 | 0.013 | 7.34±14.38 | 3.98±3.81 | 0.024 | 5.48±8.79 | 4.08±5.08 | 0.048 |

| Air Pollution at S1.5 | 25.3 | 21.8 | 0.33 | 27.2 | 21.9 | 0.21 | 23.4 | 22.2 | 0.76 |

| Paternal smoking at S1.5 | 46.8 | 39.3 | 0.036* | 36.5 | 41.2 | 0.399 | 42.7 | 40.4 | 0.608 |

| Maternal smoking at S1.5 | 35.1 | 27.1 | 0.02* | 29.8 | 28.5 | 0.819 | 29.2 | 28.4 | 0.853 |

| Paternal smoking at S4 | 43.1 | 37.3 | 0.084* | 37.5 | 38.5 | 0.915 | 41.3 | 37.8 | 0.438 |

| Maternal smoking at S4 | 32.4 | 27.1 | 0.085* | 31.7 | 27.7 | 0.42 | 29.7 | 27.8 | 0.642 |

| Mould stains at S4 | 10.6 | 4.7 | 0.003* | 14.4 | 4.8 | 0.0004* | 12.2 | 4.5 | 0.0003* |

| Weight at S4 | 16.04±2.45 | 16.15±2.56 | 0.591 | 16.50±2.77 | 16.08±2.51 | 0.114 | 16.35±2.58 | 16.07±2.53 | 0.189 |

| Height at S4 | 99.24±4.11 | 100.6±32.0 | 0.553 | 100.3±5.3 | 100.4±30.5 | 0.966 | 100.1±4.8 | 100.4±31.7 | 0.902 |

| BMI at S4 | 16.27±2.17 | 16.29±2.35 | 0.901 | 16.42±2.65 | 16.27±2.28 | 0.536 | 16.32±2.27 | 16.28±2.33 | 0.863 |

| Wheezing onset at S4 (m) | 10.52±9.36 | 7.98±5.83 | 0.002 | 9.23±8.9 | 8.78±7.03 | 0.689 | 9.52±9.05 | 8.68±6.84 | 0.401 |

| Kindergarten at S4 (m) | 21.97±10.5 | 20.97±10.8 | 0.248 | 22.98±11.1 | 20.94±10.7 | 0.068 | 21.06±10.3 | 21.18±10.9 | 0.899 |

| Physical act. at S4 (h/w) | 2.48±3.53 | 2.70±4.83 | 0.564 | 1.06±2.6 | 2.84±4.76 | <0.0001 | 1.39±2.87 | 2.93±4.86 | <0.0001 |

| TV-video at S4 (h/d) | 1.09±0.81 | 1.11±0.83 | 0.717 | 1.22±1.04 | 1.10±0.79 | 0.242 | 1.18±0.98 | 1.09±0.79 | 0.28 |

| Paternal asthma | 5.9 | 3.9 | 0.225 | 3.9 | 4.3 | 1.0 | 4.1 | 4.3 | 1.0 |

| Maternal asthma | 6.4 | 5.4 | 0.595 | 12.5 | 4.8 | 0.003* | 9.9 | 4.7 | 0.008* |

| Paternal rhinitis | 19.1 | 11.5 | 0.005* | 19.8 | 12.1 | 0.026* | 14.8 | 12.6 | 0.45 |

| Maternal rhinitis | 15.2 | 13.2 | 0.476 | 22.5 | 12.6 | 0.006* | 22.5 | 11.8 | 0.0003* |

| Paternal dermatitis | 3.3 | 4.9 | 0.436 | 8.7 | 4.1 | 0.039* | 5.9 | 4.3 | 0.417 |

| Maternal dermatitis | 7.1 | 7.6 | 1.0 | 10.7 | 7.2 | 0.233 | 10.6 | 6.9 | 0.07* |

| MedDiet during preg | 0.892 | 0.637 | 0.145 | ||||||

| 1st quartile | 27.0 | 27.4 | 23.3 | 27.8 | 28.3 | 27.2 | |||

| 2nd quartile | 39.7 | 40.3 | 41.1 | 40.1 | 36.8 | 40.8 | |||

| 3rd quartile | 17.8 | 15.5 | 20.0 | 15.5 | 21.7 | 14.8 | |||

| 4th quartile | 15.5 | 16.8 | 15.6 | 16.6 | 13.2 | 17.3 | |||

| MedDiet score during preg | 12.6±1.99 | 12.6±2.1 | 0.965 | 12.71±2.07 | 12.58±2.08 | 0.584 | 12.59±1.99 | 12.6±2.01 | 0.97 |

| Olive oil during preg | 86.8 | 87.4 | 0.806 | 83.2 | 87.8 | 0.205 | 87.5 | 87.3 | 1.0 |

| MedDiet at S4 | 0.531 | 0.02 | 0.001** | ||||||

| 1st quartile | 39.6 | 41.2 | 35.3 | 41.6 | 29.2 | 43.4 | |||

| 2nd quartile | 26.2 | 21.9 | 16.7 | 23.4 | 26.3 | 21.9 | |||

| 3rd quartile | 21.4 | 21.1 | 22.5 | 21.0 | 25.1 | 20.2 | |||

| 4th quartile | 12.8 | 15.8 | 25.5 | 14.1 | 19.3 | 14.4 | |||

| MedDiet score at S4 | 12.75±1.74 | 12.86±1.76 | 0.44 | 13.12±1.89 | 12.81±1.74 | 0.096 | 13.12±1.83 | 12.78±1.74 | 0.022 |

| Olive oil at S4 | 89.4 | 89.5 | 1.0 | 88.5 | 89.6 | 0.735 | 89.0 | 89.6 | 0.786 |

Numbers were expressed as % or media±SD, when corresponded. Bold values mean “statistical significance”.

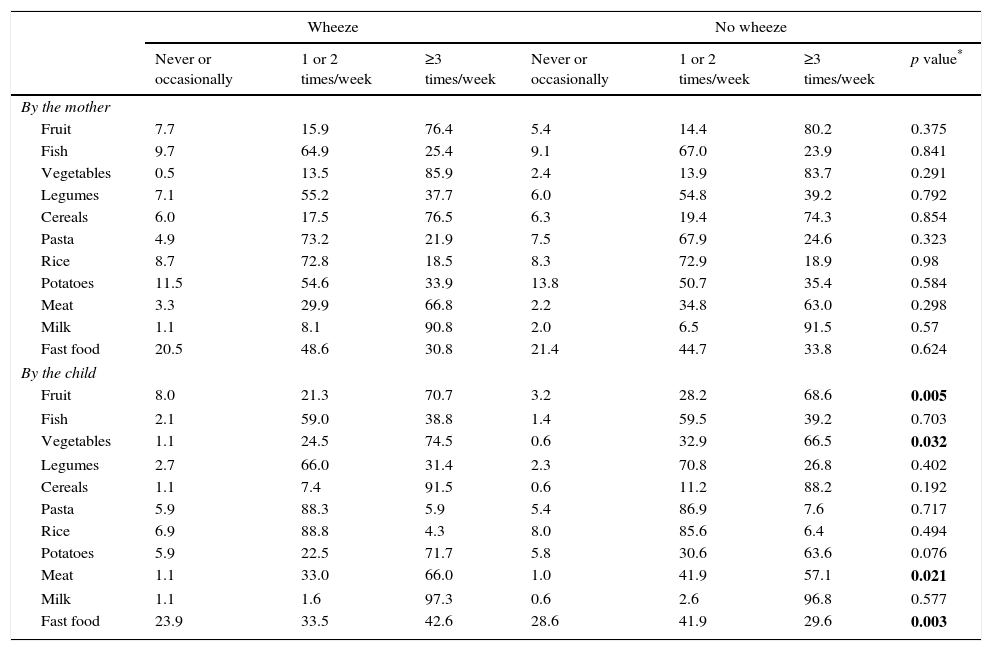

Among diet, MedDiet score adherence and olive oil consumption by the mother and by the child at survey 4 were not significantly different between children with and without current wheezing (Table 2). Also, when comparing separately each group of foods consumed by the mother and by the child, no significant differences were found. The only exception was the association between a higher prevalence of wheezing among those who never or occasionally took fruits and vegetables, and among those eating meat and fast food ≥3 times/week (Table 3a).

Prevalence (%) of the intake of different foods by the mother during pregnancy and by children at S4, among children with or without current wheezing.

| Wheeze | No wheeze | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never or occasionally | 1 or 2 times/week | ≥3 times/week | Never or occasionally | 1 or 2 times/week | ≥3 times/week | p value* | |

| By the mother | |||||||

| Fruit | 7.7 | 15.9 | 76.4 | 5.4 | 14.4 | 80.2 | 0.375 |

| Fish | 9.7 | 64.9 | 25.4 | 9.1 | 67.0 | 23.9 | 0.841 |

| Vegetables | 0.5 | 13.5 | 85.9 | 2.4 | 13.9 | 83.7 | 0.291 |

| Legumes | 7.1 | 55.2 | 37.7 | 6.0 | 54.8 | 39.2 | 0.792 |

| Cereals | 6.0 | 17.5 | 76.5 | 6.3 | 19.4 | 74.3 | 0.854 |

| Pasta | 4.9 | 73.2 | 21.9 | 7.5 | 67.9 | 24.6 | 0.323 |

| Rice | 8.7 | 72.8 | 18.5 | 8.3 | 72.9 | 18.9 | 0.98 |

| Potatoes | 11.5 | 54.6 | 33.9 | 13.8 | 50.7 | 35.4 | 0.584 |

| Meat | 3.3 | 29.9 | 66.8 | 2.2 | 34.8 | 63.0 | 0.298 |

| Milk | 1.1 | 8.1 | 90.8 | 2.0 | 6.5 | 91.5 | 0.57 |

| Fast food | 20.5 | 48.6 | 30.8 | 21.4 | 44.7 | 33.8 | 0.624 |

| By the child | |||||||

| Fruit | 8.0 | 21.3 | 70.7 | 3.2 | 28.2 | 68.6 | 0.005 |

| Fish | 2.1 | 59.0 | 38.8 | 1.4 | 59.5 | 39.2 | 0.703 |

| Vegetables | 1.1 | 24.5 | 74.5 | 0.6 | 32.9 | 66.5 | 0.032 |

| Legumes | 2.7 | 66.0 | 31.4 | 2.3 | 70.8 | 26.8 | 0.402 |

| Cereals | 1.1 | 7.4 | 91.5 | 0.6 | 11.2 | 88.2 | 0.192 |

| Pasta | 5.9 | 88.3 | 5.9 | 5.4 | 86.9 | 7.6 | 0.717 |

| Rice | 6.9 | 88.8 | 4.3 | 8.0 | 85.6 | 6.4 | 0.494 |

| Potatoes | 5.9 | 22.5 | 71.7 | 5.8 | 30.6 | 63.6 | 0.076 |

| Meat | 1.1 | 33.0 | 66.0 | 1.0 | 41.9 | 57.1 | 0.021 |

| Milk | 1.1 | 1.6 | 97.3 | 0.6 | 2.6 | 96.8 | 0.577 |

| Fast food | 23.9 | 33.5 | 42.6 | 28.6 | 41.9 | 29.6 | 0.003 |

Bold values mean “statistical significance”.

Prevalence (%) of the intake of different foods by the mother during pregnancy and by children at S4, among children with and without current rhinitis.

| Rhinitis | No rhinitis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never or occasionally | 1 or 2 times/week | ≥3 times/week | Never or occasionally | 1 or 2 times/week | ≥3 times/week | p value* | |

| By the mother | |||||||

| Fruit | 8.0 | 19.0 | 73.0 | 5.6 | 14.2 | 80.2 | 0.202 |

| Fish | 5.9 | 68.6 | 25.5 | 9.7 | 66.3 | 24.0 | 0.491 |

| Vegetables | 2.0 | 14.7 | 83.3 | 2.1 | 13.7 | 84.2 | 0.932 |

| Legumes | 10.3 | 50.5 | 39.2 | 5.7 | 55.3 | 38.9 | 0.21 |

| Cereals | 7.0 | 18.0 | 75.0 | 6.2 | 19.2 | 74.6 | 0.911 |

| Pasta | 9.8 | 64.7 | 25.5 | 6.7 | 69.4 | 23.9 | 0.399 |

| Rice | 6.9 | 69.3 | 23.8 | 8.5 | 73.3 | 18.2 | 0.392 |

| Potatoes | 11.1 | 50.5 | 38.4 | 13.7 | 51.6 | 34.8 | 0.717 |

| Meat | 2.0 | 33.7 | 64.4 | 2.4 | 33.9 | 63.7 | 1.0 |

| Milk | 3.9 | 4.9 | 91.2 | 1.6 | 7.0 | 91.4 | 0.171 |

| Fast food | 22.5 | 43.1 | 34.3 | 21.1 | 45.8 | 33.1 | 0.857 |

| By the child | |||||||

| Fruit | 9.6 | 9.6 | 80.8 | 3.5 | 28.9 | 67.6 | <0.0001 |

| Fish | 4.8 | 48.1 | 47.1 | 1.1 | 60.7 | 38.2 | 0.003 |

| Vegetables | 1.9 | 12.5 | 85.6 | 0.6 | 33.5 | 66 | <0.0001 |

| Legumes | 1.9 | 64.4 | 33.7 | 2.5 | 70.5 | 27.0 | 0.352 |

| Cereals | 1.0 | 7.7 | 91.3 | 0.7 | 10.8 | 88.5 | 0.42 |

| Pasta | 7.7 | 78.8 | 13.5 | 5.2 | 88.2 | 6.6 | 0.02 |

| Rice | 6.7 | 85.6 | 7.7 | 7.9 | 86.3 | 5.8 | 0.652 |

| Potatoes | 2.0 | 14.7 | 83.3 | 6.3 | 30.7 | 63.1 | 0.0001 |

| Meat | 1.0 | 17.3 | 81.7 | 1.0 | 42.9 | 56.1 | <0.0001 |

| Milk | 2.9 | 0.0 | 97.1 | 0.4 | 2.7 | 96.9 | 0.01 |

| Fast food | 15.4 | 47.1 | 37.5 | 29.1 | 39.5 | 31.4 | 0.008 |

Bold values mean “statistical significance”.

Prevalence (%) of the intake of different foods by the mother during pregnancy and by children at S4, among children with and without current dermatitis.

| Dermatitis | No dermatitis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never or occasionally | 1 or 2 times/week | ≥3 times/week | Never or occasionally | 1 or 2 times/week | ≥3 times/week | p value* | |

| By the mother | |||||||

| Fruit | 4.2 | 13.3 | 82.5 | 6.2 | 15.0 | 78.8 | 0.54 |

| Fish | 7.2 | 66.5 | 26.3 | 9.7 | 66.7 | 23.6 | 0.527 |

| Vegetables | 3.0 | 14.3 | 82.7 | 1.9 | 13.8 | 84.4 | 0.559 |

| Legumes | 6.1 | 56.4 | 37.4 | 6.2 | 54.5 | 39.3 | 0.894 |

| Cereals | 6.7 | 17.2 | 76.1 | 6.2 | 19.4 | 74.4 | 0.81 |

| Pasta | 6.1 | 65.5 | 28.5 | 7.3 | 69.6 | 23.2 | 0.353 |

| Rice | 10.4 | 68.9 | 20.7 | 7.9 | 73.6 | 18.4 | 0.387 |

| Potatoes | 12.9 | 50.9 | 36.2 | 13.4 | 51.6 | 35.0 | 0.963 |

| Meat | 2.4 | 31.1 | 66.3 | 2.4 | 34.5 | 63.2 | 0.737 |

| Milk | 1.2 | 4.2 | 94.6 | 2.0 | 7.3 | 90.7 | 0.311 |

| Fast food | 15.0 | 43.7 | 41.3 | 22.6 | 45.8 | 31.6 | 0.02 |

| By the child | |||||||

| Fruit | 8.7 | 9.9 | 81.4 | 3.1 | 30.5 | 66.3 | <0.0001 |

| Fish | 3.5 | 52.3 | 44.2 | 1.1 | 60.8 | 38.1 | 0.016 |

| Vegetables | 0.6 | 16.9 | 82.6 | 0.7 | 34.3 | 64.9 | <0.0001 |

| Legumes | 1.7 | 68.0 | 30.2 | 2.5 | 70.4 | 27.1 | 0.663 |

| Cereals | 1.2 | 7.0 | 91.9 | 0.6 | 11.2 | 88.1 | 0.141 |

| Pasta | 8.1 | 84.9 | 7.0 | 5.0 | 87.7 | 7.4 | 0.257 |

| Rice | 8.1 | 86.6 | 5.2 | 7.7 | 86.1 | 6.2 | 0.901 |

| Potatoes | 5.3 | 14.6 | 80.1 | 5.9 | 32.1 | 62.0 | <0.0001 |

| Meat | 1.7 | 25.0 | 73.3 | 0.8 | 43.4 | 55.7 | <0.0001 |

| Milk | 2.9 | 0.6 | 96.5 | 0.2 | 2.8 | 97.0 | 0.001 |

| Fast food | 23.8 | 44.2 | 32.0 | 28.5 | 39.4 | 32.0 | 0.382 |

Bold values mean “statistical significance”.

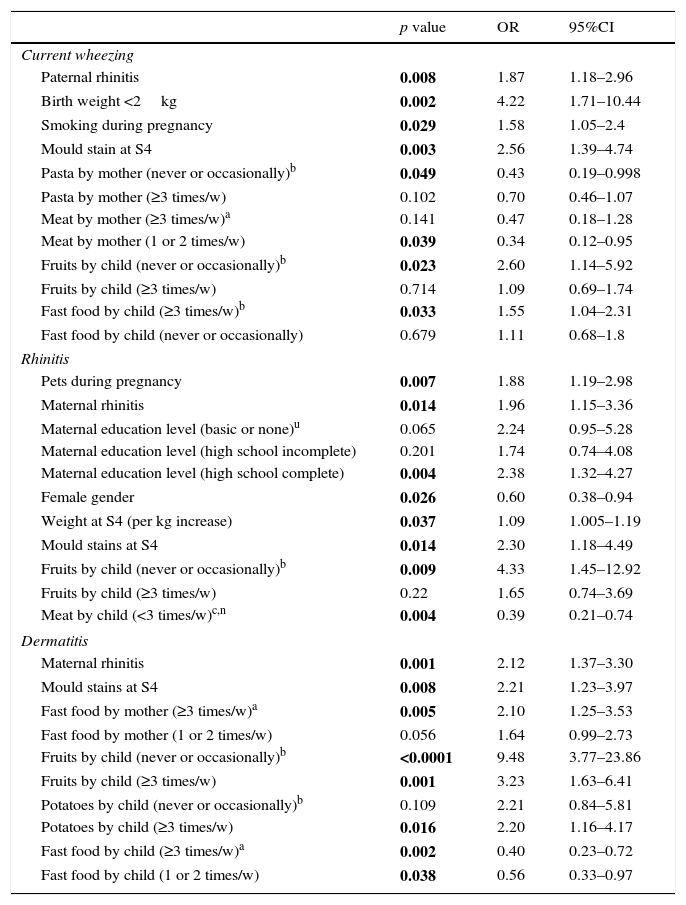

In the multiple logistic regression analysis parental rhinitis; birth weight below 2kg; maternal tobacco during pregnancy; mould stains in household walls at survey 4; having fruit never or occasionally; and consuming ≥3 times/week fast food by the child remained as independent risk factors associated to current wheezing. While consumption by the mother during pregnancy of meat 1 or 2 times/week, and never or occasionally pasta, remained as independent protective factors for current wheezing in the offspring, (Table 4).

Multivariate analysis for factors associated to current wheezing, rhinitis and dermatitis at survey 4.*

| p value | OR | 95%CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current wheezing | |||

| Paternal rhinitis | 0.008 | 1.87 | 1.18–2.96 |

| Birth weight <2kg | 0.002 | 4.22 | 1.71–10.44 |

| Smoking during pregnancy | 0.029 | 1.58 | 1.05–2.4 |

| Mould stain at S4 | 0.003 | 2.56 | 1.39–4.74 |

| Pasta by mother (never or occasionally)b | 0.049 | 0.43 | 0.19–0.998 |

| Pasta by mother (≥3 times/w) | 0.102 | 0.70 | 0.46–1.07 |

| Meat by mother (≥3 times/w)a | 0.141 | 0.47 | 0.18–1.28 |

| Meat by mother (1 or 2 times/w) | 0.039 | 0.34 | 0.12–0.95 |

| Fruits by child (never or occasionally)b | 0.023 | 2.60 | 1.14–5.92 |

| Fruits by child (≥3 times/w) | 0.714 | 1.09 | 0.69–1.74 |

| Fast food by child (≥3 times/w)b | 0.033 | 1.55 | 1.04–2.31 |

| Fast food by child (never or occasionally) | 0.679 | 1.11 | 0.68–1.8 |

| Rhinitis | |||

| Pets during pregnancy | 0.007 | 1.88 | 1.19–2.98 |

| Maternal rhinitis | 0.014 | 1.96 | 1.15–3.36 |

| Maternal education level (basic or none)u | 0.065 | 2.24 | 0.95–5.28 |

| Maternal education level (high school incomplete) | 0.201 | 1.74 | 0.74–4.08 |

| Maternal education level (high school complete) | 0.004 | 2.38 | 1.32–4.27 |

| Female gender | 0.026 | 0.60 | 0.38–0.94 |

| Weight at S4 (per kg increase) | 0.037 | 1.09 | 1.005–1.19 |

| Mould stains at S4 | 0.014 | 2.30 | 1.18–4.49 |

| Fruits by child (never or occasionally)b | 0.009 | 4.33 | 1.45–12.92 |

| Fruits by child (≥3 times/w) | 0.22 | 1.65 | 0.74–3.69 |

| Meat by child (<3 times/w)c,n | 0.004 | 0.39 | 0.21–0.74 |

| Dermatitis | |||

| Maternal rhinitis | 0.001 | 2.12 | 1.37–3.30 |

| Mould stains at S4 | 0.008 | 2.21 | 1.23–3.97 |

| Fast food by mother (≥3 times/w)a | 0.005 | 2.10 | 1.25–3.53 |

| Fast food by mother (1 or 2 times/w) | 0.056 | 1.64 | 0.99–2.73 |

| Fruits by child (never or occasionally)b | <0.0001 | 9.48 | 3.77–23.86 |

| Fruits by child (≥3 times/w) | 0.001 | 3.23 | 1.63–6.41 |

| Potatoes by child (never or occasionally)b | 0.109 | 2.21 | 0.84–5.81 |

| Potatoes by child (≥3 times/w) | 0.016 | 2.20 | 1.16–4.17 |

| Fast food by child (≥3 times/w)a | 0.002 | 0.40 | 0.23–0.72 |

| Fast food by child (1 or 2 times/w) | 0.038 | 0.56 | 0.33–0.97 |

Bold values mean “statistical significance”.

There were significant associations with current rhinitis with the following factors in the univariate analyses (Table 2): male gender; maternal asthma; paternal rhinitis; maternal rhinitis; paternal dermatitis; dog/cat ownership at birth; dog/cat ownership at survey 1.5; mould stains on the household at survey 1.5 and at survey 4. Furthermore, as compared to those without current rhinitis, children with current rhinitis had a lower proportion of mothers with university degrees; a higher number of colds during the first year of life; and lower physical activity (Table 2).

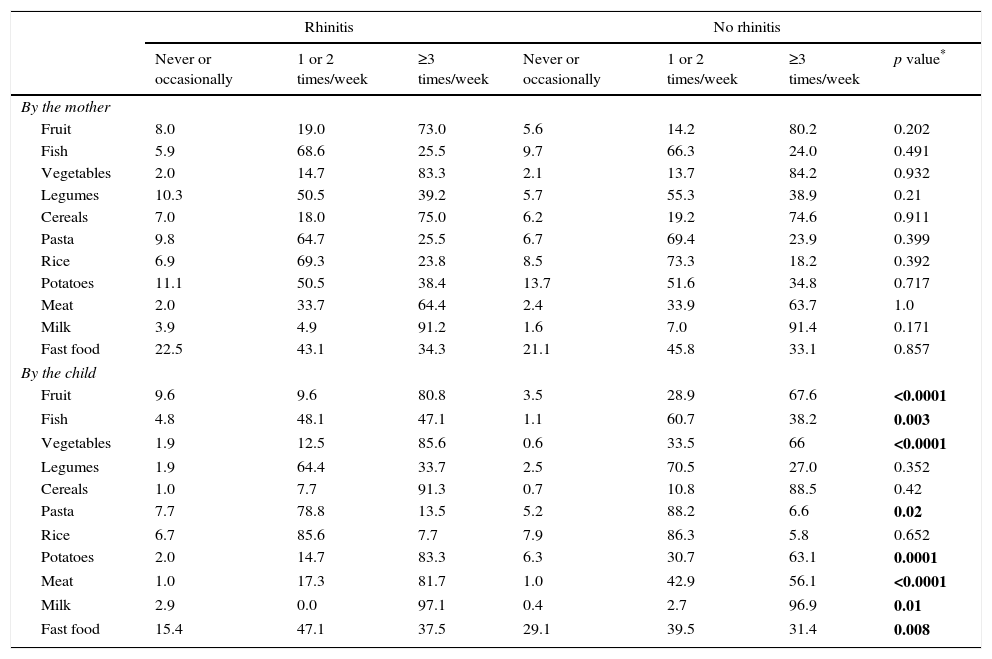

MedDiet score adherence by the mother and olive oil consumption by the mother and by the child were not significantly different between children with and with current rhinitis (Table 2). However, children without current rhinitis had significantly lower MedDiet adherence at survey 4 (using quartiles of MedDiet) (Table 2). Separately considering each group of foods consumed by the mother and by the child at survey 4, when comparing children with and without rhinitis, those with current rhinitis had a significantly higher proportion of high consumption (≥3 times/week) of fruits, fish, vegetables, pasta, potatoes and meat; a higher proportion of low consumption (never or occasionally) of milk by the child; and a lower proportion of fast food consumption by the child (Table 3b).

In the multiple logistic regression analysis, pets at birth; maternal rhinitis; higher maternal education level; increased weight; and mould stains at survey 4 remained independent risk factors associated to current rhinitis; as did low consumption (never or occasionally) of fruits by the child. Female gender and consuming meat<than 3 times/week by the child were protective factors (Table 4).

Current dermatitis at survey 4There was a higher proportion of maternal asthma, maternal rhinitis, mould stains on the household at survey 4 among children with current dermatitis than without it (Table 2). Moreover, mothers of children with current dermatitis had a significantly higher frequency (>once per week) of paracetamol use during pregnancy; and children had more colds during the first year of life, and exercised less than those without dermatitis (Table 2).

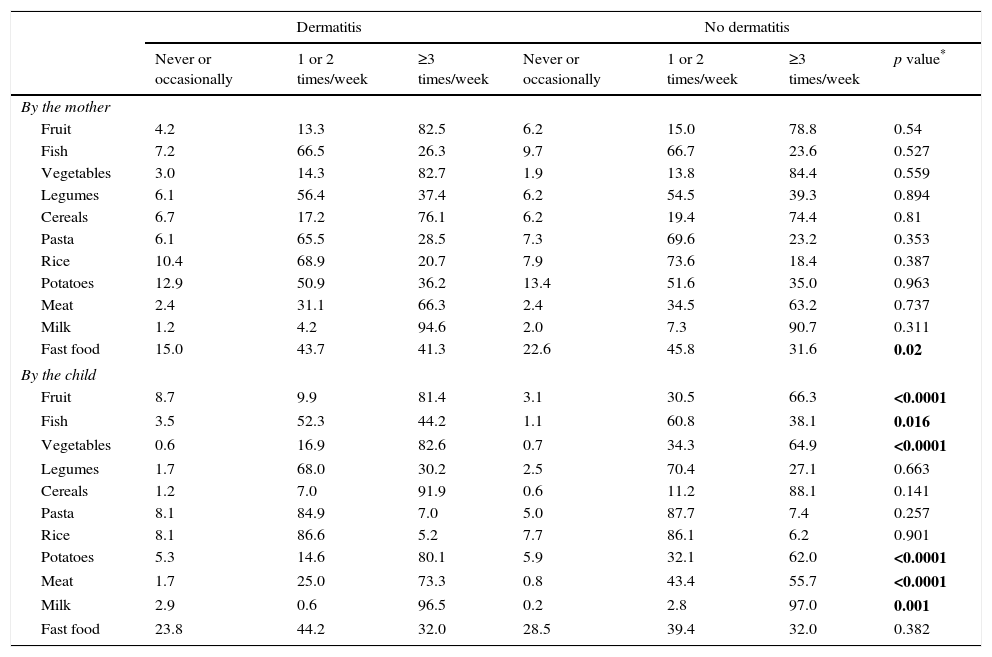

MedDiet score adherence consumption by the mother during pregnancy; and olive oil consumption by the mother and by the child at survey 4 were not significantly different between children with current dermatitis than those without (Table 2). However, children with current dermatitis had higher MedDiet consumption (in quartiles and score) by child (Table 2). Comparing separately each group of foods consumed by the mother and by the child at survey 4, children with current dermatitis had a higher proportion of consumption of ≥3 times/week of fruits, fish, vegetables, potatoes and meat than those without dermatitis. Additionally, those without dermatitis had a lower proportion of never or occasional consumption of milk.

In the multiple logistic regression analysis, maternal rhinitis; mould stains at survey 4; ≥3 times/week fast food consumption by the mother; never or occasionally and ≥3 times/week fruits consumption by the child; and ≥3 times/week potatoes consumption by the child remained associated to higher risk of current dermatitis. Curiously, 1 or 2 times/week or ≥3 times/week fast food consumption by the child were a protective factor for dermatitis.

DiscussionThe present study showed that children never or occasionally consuming fruit and having fast food ≥3 times/week had a higher risk for current wheezing; while maternal consumption during pregnancy of meat 1 or 2 times/week, and pasta never or occasionally remained as protective factors. For current rhinitis, children never or occasionally consuming fruits were at higher risk; while consuming meat <3 times/week was protective. Finally, for current dermatitis, maternal consumption of fast food ≥3 times/week, and children consumption of fruits never/occasionally or ≥3 times/week, and potatoes ≥3 times/week was associated to higher risk. Curiously, children consuming fast food 1 or 2 times/week or ≥3 times/week had a lower prevalence of the condition. MedDiet did not remain as a protective factor for wheeze, dermatitis or rhinitis.

A recent meta-analysis6 (N=32 studies, 29 cohorts) found a protective effect of maternal dietary intake of three vitamins/nutrients (vitamin D, vitamin E, and zinc) against wheeze during childhood. However, none of these nutrients were consistently associated with asthma or with other atopic conditions, and thus there is inconclusive evidence for either a true cause–effect relationship or the mechanisms underlying our findings. Higher maternal intake of magnesium and vegetables was associated with a lower risk of eczema; higher copper consumption was associated with a lower risk of food allergy; and MedDiet was associated with lower risk of positive skin prick test.

Furthermore, another meta-analysis12 showed that serum vitamin A was lower in children with asthma as compared with controls. High maternal dietary vitamin D and E intakes during pregnancy were protective for the development of wheezing. Adherence to a MedDiet was protective for persistent wheeze and atopy. Seventeen of 22 fruit and vegetable studies report a beneficial association with asthma and allergic condition. Vitamin C and selenium were not related with this wheeze/asthma and atopy.

There are several variants of the MedDiet, but some common components are: high monounsaturated/saturated fat ratio; high consumption of vegetables, fruit, legumes, and grains and moderate consumption of milk and dairy products.13 Thus MedDiet is a diet rich in both antioxidants and cis monounsaturated fatty acids. A recent meta-analysis showed that MedDiet consumed by the mother was a protective factor for atopic diseases in the offspring.6 Also a meta-analysis on the adherence to MedDiet in children (N=8 studies, 39804 children aged 3–18 yrs) showed a trend to be associated with lower occurrence of current wheeze, current severe wheeze, or ever asthma.9 However, in the present study, MedDiet consumption by the mother during pregnancy or by the child during the previous year was not a protective factor for current wheezing, rhinitis, or dermatitis in preschoolers.

The potential explanations of this negative result about MedDiet as a protective factor for wheezing and allergic diseases could be that other factors blunt its effect. Indeed, in our study other factors remain as a risk for wheezing (e.g. parental rhinitis, birth weight below 2kg, maternal tobacco use during pregnancy, mould stains at survey 4), for rhinitis (e.g. pets at birth, maternal rhinitis, higher maternal education level, increased weight and mould stains at survey 4) and for dermatitis (e.g. maternal rhinitis, mould stains at survey 4). All of these are well recognised risk factors for those diseases.14

There are some potential limitations in the present study. Firstly, an information bias on food intake could be present. However, it has been shown that parents are reliable when reporting food intake of their children, especially with fruit and vegetables.15 Additionally and unfortunately, our food questionnaires did not allow to correct for the energy intake; nevertheless most studies on diet and asthma in children do not correct for this parameter either.16 Secondly, a bias on reported height and weight could also be present; however, a prior study carried out in the same area showed that height and weight reported by parents are reliable for epidemiological studies.17 Finally, as in all cross-sectional studies, this one cannot show the association over time, and recall bias may be present. Thus, prospective studies on the relationship between asthma and diet should be carried out, especially during foetal and early life,3,16 to understand the potential of food for preventing asthma and allergic diseases.

In conclusion, our results suggest that low consumption of fruits and high of meat by the child, and high consumption of potatoes and pasta by the mother had a negative effect on wheezing, rhinitis or dermatitis; while fast food consumption by mother and child were inconsistent.

Ethical disclosuresPatients’ data protectionThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data and that all the patients included in the study have received sufficient information and have given their informed consent in writing to participate in that study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects mentioned in the article. The author for correspondence is in possession of this document.

Protection of human subjects and animals in researchThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

We thank Anthony Carlson for his editorial assistance.