With the objective of making informed decisions on resource allocation, there is a critical need for studies that provide accurate information on hospital costs for treating respiratory syncytial virus (RSV)-related bronchiolitis, mainly in middle-income countries (MICs). The aim of the present study was to evaluate the direct medical costs associated with bronchiolitis hospitalizations caused by infection with RSV in Bogota, Colombia.

Material and methodsWe reviewed the available electronic medical records (EMRs) for all infants younger than two years of age who were admitted to the Fundacion Hospital de La Misericordia with a discharge principal diagnosis of RSV-related bronchiolitis over a 24-month period from January 2016 to December 2017. Direct medical costs of RSV-related bronchiolitis were retrospectively collected by dividing the infants into three groups: those requiring admission to the pediatric ward (PW) only, those requiring admission to the pediatric intermediate care unit (PIMC), and those requiring to the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU).

ResultsA total of 89 patients with a median (IQR) age of 7.1 (3.1–12.2) months were analyzed of whom 20 (56.2%) were males. Overall, the median (IQR) cost of infants treated in the PW, in the PIMC, and in the PICU was US$518.0 (217.0–768.9) vs. 1305.2 (1051.4–1492.2) vs. 2749.7 (1372.7–4159.9), respectively, with this difference being statistically significant (p<0.001).

ConclusionsThe present study helps to further our understanding of the economic burden of RSV-related bronchiolitis hospitalizations among infants of under two years of age in a middle-income tropical country.

Acute bronchiolitis is the most important cause of lower respiratory tract infection in children during the first two years of life and is the leading cause of hospitalization for infants beyond the neonatal period.1 Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is the most commonly identified virus, being responsible for approximately 60% of bronchiolitis cases.2–4 Recent reports have shown that RSV-related infection is an important cause of death in children in younger children, especially in those with comorbidities.5

The disease places a large economic burden, not only on healthcare systems, but also on families and society as a whole,6 mainly in middle-income countries (MICs).7 Recent studies reporting an increase in the rate of hospitalization over the last decades point to the growing resource utilization, costs and public health burden of the disease.8 The substantial clinical and economic burden of RSV-related bronchiolitis hospitalizations justifies continuing efforts that have been made to prevent or attenuate the RSV disease both through active and passive immunizations especially among high-risk infants.9

Understanding the costs associated with the management of RSV-related bronchiolitis hospitalizations is essential in terms of public policy considerations for deciding on resource allocation and setting priorities for child health. Recent reports have suggested that perinatal immunization strategies for children aged younger than six months could have a substantial impact on RSV-related child mortality in MICs.5 However, the RSV immunoprophylaxis is costly, and its cost-effectiveness has been demonstrated only in selected high-risk group of infants.10,11 Currently, a phase 3 clinical trial is ongoing to determine the efficacy of a RSV vaccine for infants via maternal immunization, with objective measures of medical significance of lower respiratory tract infection from 90 to 180 days of life in infants.12 Accordingly, there is a critical need for studies that provide accurate information on hospital costs for treating RSV-related bronchiolitis. The latter is essential for making informed decisions on resource allocation and for providing an input into price negotiations for current and newer RSV vaccines, and consequently to help to ensure the most efficient use of health resources, especially in MICs, where these resources are always scarce. However, despite its importance, a literature review reveals a scarcity of published data regarding hospital costs for treating RSV infections in MICs. Although several studies in high-income countries have reported the costs associated with episodes of bronchiolitis, only little knowledge exists about treatment costs in MICs.

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the direct medical costs associated with bronchiolitis hospitalizations caused by infection with RSV among infants under two years of age residing in Bogota, Colombia, a tropical MIC located in South America.

Material and methodsStudy designWe reviewed the available electronic medical records (EMRs) for all infants under two years of age who were admitted to the Fundacion Hospital de La Misericordia with a discharge principal diagnosis of RSV-related bronchiolitis over a 24-month period from January 2016 to December 2017. In our institution bronchiolitis is defined as the first wheezing episode younger than 24 months of age. Direct medical costs of RSV-related bronchiolitis were retrospectively collected by dividing the infants into three groups: those requiring admission to the pediatric ward (PW) only, those requiring admission to the pediatric intermediate care unit (PIMC), and those requiring to the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU). In our institution, the admission criteria to the PIMC for acute bronchiolitis include one or more of the following criteria: worsening hypoxemia or hypercapnia, worsening respiratory distress, continuing requirement for more than 50% oxygen, hemodynamic instability, altered mental state, or apnea. Additionally, patients with respiratory failure and need for invasive or non-invasive mechanical ventilation are transferred to the PICU. All children hospitalized, but not those treated on an outpatient basis; since acute lower respiratory infections are routinely tested at admission for RSV using a rapid immunochromatographic test method (RSV Respi-Strip; Coris BioConcept, Gembloux, Belgium). Consequently, we excluded all patients with a primary diagnosis of bronchiolitis treated on an outpatient basis (including patients that were only treated in the emergency department) from our analyses. Likewise, we excluded patients whose confirmed RSV infection was an incidental finding and was judged not to be the cause of the patient's hospitalization.

Eligible infants with a discharge principal diagnosis of RSV-related bronchiolitis were identified by International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-10 code J21.0.

Study siteBogota, the capital city of Colombia, a tropical MIC located in South America, contains one fifth of Colombia's population, and is located at an elevation of about 2650m (8660ft) above sea level. Although RSV is active in the city throughout the year, it peaks during the three-month period from March to May, the first rainy period of the year in the city.13 The Fundacion Hospital La Misericordia is a tertiary care university-based children's hospital located in the metropolitan area of Bogota that receives patients from the majority and most representative medical insurance companies in the city.

Cost analysisDirect medical and non-medical cost data were collected from the healthcare provider's perspective. The following clinical and resource utilization data, which in turn were grouped into four categories were extracted from EMRs of included patients: medical and therapy services (including respiratory therapy), diagnostics tests and procedures (hemogram, C-reactive protein, viral respiratory panel, and imagenologic studies), consumables (medications, fluids, supplies, nebulization and oxygen treatment), and hotel services (hospital stay). Resources quantities at an individual patient level including length of stay-LOS, the quantity of medications and supplies utilized, and the number of diagnostic tests and procedures were collected.

The unit costs of each of the components of the four above-mentioned categories, including the bed-cost per day were primarily obtained from hospital accounting reports.

Thereafter we calculated the cost per bronchiolitis episode hospitalization based on the unit cost of each component multiplied by the resources’ quantities utilized by each patient.

Costs were calculated and presented separately in three groups based on the hospital service to which the patient was admitted: (1) patients admitted to the PW only (PW group); (2) patients admitted to the PIMC, with or without admission to the PW, but without admission to the PICU (PIMC group); and (3) patients with admission to the PICU, with or without admission to the PIMC or to the PW (PICU group).

Costs were calculated in Colombian pesos (COPs) and converted to dollars (US$) based on the average exchange rate for 2017 (1US$=2951.32 COP).14 All the costs were adjusted to 2017 COPs before converting them to US$.

The study protocol was approved by the local ethics board.

Statistical analysisContinuous variables are presented as mean standard deviation (SD) or median interquartile range (IQR), depending on the normality of the data distribution. Normality of the continuous variables distributions was assessed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Categorical variables are presented as numbers (percentage). As was mentioned above, the results were calculated and presented separately for the following three groups: PW, PIMC, and the PICU group.

Differences in hospitalization costs between patients assigned to each one of the three groups were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the post hoc Tukey test or the non-parametric ANOVA (Kruskal–Wallis) test, also depending on the normality of the data distribution.

All statistical tests were two-tailed, and the significance level used was 0.05. The data were analyzed with the Statistical Package Stata 12.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas, USA).

ResultsStudy populationDuring the study period, 89 patients had a discharge principal diagnosis of RSV-related bronchiolitis. Of the 89 patients included, 20 (56.2%) were males, and the median (IQR) age was 7.1 (3.1–12.2) months, with the infants requiring admission to the PW being older when compared with the other two groups, although this difference was not statistically significant (8.9 (6.2–12.6) vs. 3.48 (2.1–12.9) vs. 5.1 (3.1–12.7) months, for the PW, PIMC, and PICU groups, respectively, p=0.114). The age group distribution was: 37 (41.6%) under six months, 27 (30.3%) between seven and 12 months, and the remaining 25 (28.1%) between 13 and 24 months. Out of the total of 89 hospital events analyzed, 52 (58.4%) occurred between months of March and June, the period of time that roughly coincides with the first rainy season in the city.13 Regarding LOS, the mean±SD was 7.0±4.4 days overall, being this value significantly lower for infants requiring admission to the PW when compared with those requiring admission to the PIMC and to the PICU (4.4±3.2 vs. 9.0±4.1 vs. 10.2±3.8, respectively, p<0.001).

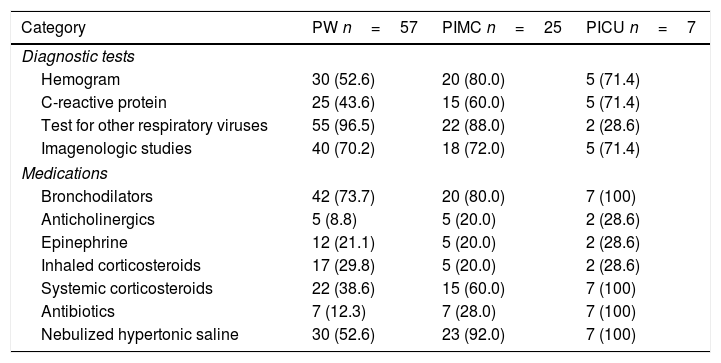

Diagnostic tests ordered and medications prescribedOverall, the diagnostic tests most frequently ordered by the attending physicians were viral respiratory panels to test for other respiratory viruses in 79 (88.8%) and chest radiography in 62 (69.7%) patients. The medications most often prescribed were nebulized or inhaled beta 2 agonists in 69 (77.5%), and nebulized hypertonic saline in 59 (67.6%) patients. The diagnostic test most frequently ordered and the medications most often prescribed, stratified by the hospital service in which the patient was admitted, are presented in Table 1.

Diagnostic test most frequently ordered, and the medications most often prescribed stratified by the hospital service in which the patient was admitted.a

| Category | PW n=57 | PIMC n=25 | PICU n=7 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic tests | |||

| Hemogram | 30 (52.6) | 20 (80.0) | 5 (71.4) |

| C-reactive protein | 25 (43.6) | 15 (60.0) | 5 (71.4) |

| Test for other respiratory viruses | 55 (96.5) | 22 (88.0) | 2 (28.6) |

| Imagenologic studies | 40 (70.2) | 18 (72.0) | 5 (71.4) |

| Medications | |||

| Bronchodilators | 42 (73.7) | 20 (80.0) | 7 (100) |

| Anticholinergics | 5 (8.8) | 5 (20.0) | 2 (28.6) |

| Epinephrine | 12 (21.1) | 5 (20.0) | 2 (28.6) |

| Inhaled corticosteroids | 17 (29.8) | 5 (20.0) | 2 (28.6) |

| Systemic corticosteroids | 22 (38.6) | 15 (60.0) | 7 (100) |

| Antibiotics | 7 (12.3) | 7 (28.0) | 7 (100) |

| Nebulized hypertonic saline | 30 (52.6) | 23 (92.0) | 7 (100) |

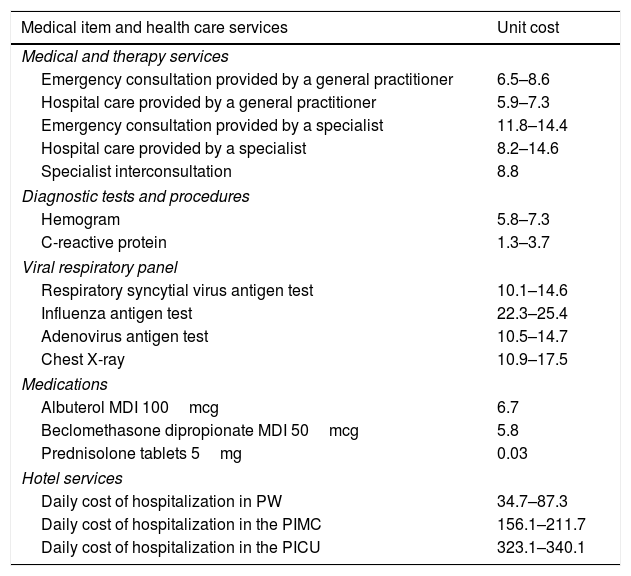

Unit costs of direct medical items and health care services are presented in Table 2.

Unit costs of direct medical items and health care services.a

| Medical item and health care services | Unit cost |

|---|---|

| Medical and therapy services | |

| Emergency consultation provided by a general practitioner | 6.5–8.6 |

| Hospital care provided by a general practitioner | 5.9–7.3 |

| Emergency consultation provided by a specialist | 11.8–14.4 |

| Hospital care provided by a specialist | 8.2–14.6 |

| Specialist interconsultation | 8.8 |

| Diagnostic tests and procedures | |

| Hemogram | 5.8–7.3 |

| C-reactive protein | 1.3–3.7 |

| Viral respiratory panel | |

| Respiratory syncytial virus antigen test | 10.1–14.6 |

| Influenza antigen test | 22.3–25.4 |

| Adenovirus antigen test | 10.5–14.7 |

| Chest X-ray | 10.9–17.5 |

| Medications | |

| Albuterol MDI 100mcg | 6.7 |

| Beclomethasone dipropionate MDI 50mcg | 5.8 |

| Prednisolone tablets 5mg | 0.03 |

| Hotel services | |

| Daily cost of hospitalization in PW | 34.7–87.3 |

| Daily cost of hospitalization in the PIMC | 156.1–211.7 |

| Daily cost of hospitalization in the PICU | 323.1–340.1 |

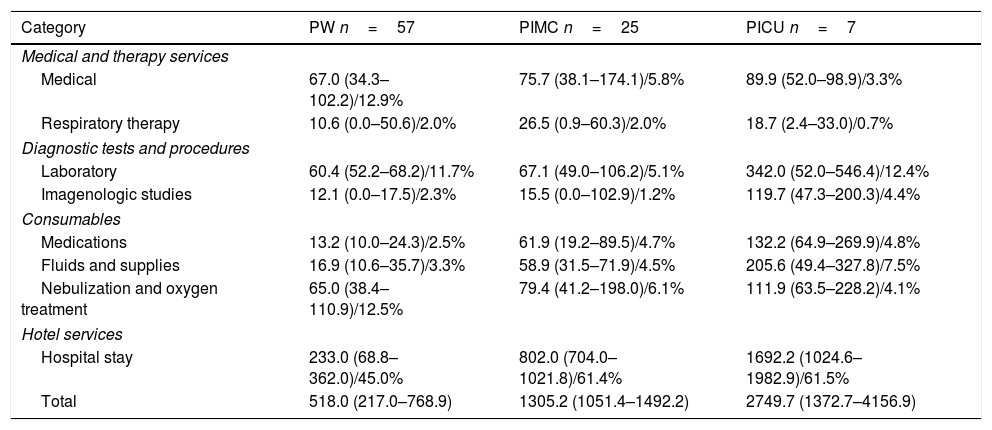

With respect to the hospital service in which the patient was admitted, overall, the median (IQR) cost of infants treated in the PW, in the PIMC, and in the PICU was US$518.0 (217.0–768.9) vs. 1305.2 (1051.4–1492.2) vs. 2749.7 (1372.7–4159.9), respectively, with this difference being statistically significant (p<0.001). The in-patient care costs of infants treated in the PIMC or in the PICU were approximately 5.0–2.5 times greater than those for infants treated in the PW. Infants<1 year accounted for most of this overall cost, especially in those treated in the PW, with a median (IQR) cost of US$1019.8 (638.2–1489.2).

With regard to the proportion of resources and services billed according to the hospital setting in which the patients were admitted, in general, the more severely ill the patient, the greater the percentage of the bill was attributable to hotel services (hospital stay), fluids and supplies, and medications, and the lesser the percentage of the bill was attributable to medical services and nebulization and oxygen therapy (Table 3).

Total median costs associated with RSV-related bronchiolitis stratified by the hospital service in which the patient was admitted.a

| Category | PW n=57 | PIMC n=25 | PICU n=7 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medical and therapy services | |||

| Medical | 67.0 (34.3–102.2)/12.9% | 75.7 (38.1–174.1)/5.8% | 89.9 (52.0–98.9)/3.3% |

| Respiratory therapy | 10.6 (0.0–50.6)/2.0% | 26.5 (0.9–60.3)/2.0% | 18.7 (2.4–33.0)/0.7% |

| Diagnostic tests and procedures | |||

| Laboratory | 60.4 (52.2–68.2)/11.7% | 67.1 (49.0–106.2)/5.1% | 342.0 (52.0–546.4)/12.4% |

| Imagenologic studies | 12.1 (0.0–17.5)/2.3% | 15.5 (0.0–102.9)/1.2% | 119.7 (47.3–200.3)/4.4% |

| Consumables | |||

| Medications | 13.2 (10.0–24.3)/2.5% | 61.9 (19.2–89.5)/4.7% | 132.2 (64.9–269.9)/4.8% |

| Fluids and supplies | 16.9 (10.6–35.7)/3.3% | 58.9 (31.5–71.9)/4.5% | 205.6 (49.4–327.8)/7.5% |

| Nebulization and oxygen treatment | 65.0 (38.4–110.9)/12.5% | 79.4 (41.2–198.0)/6.1% | 111.9 (63.5–228.2)/4.1% |

| Hotel services | |||

| Hospital stay | 233.0 (68.8–362.0)/45.0% | 802.0 (704.0–1021.8)/61.4% | 1692.2 (1024.6–1982.9)/61.5% |

| Total | 518.0 (217.0–768.9) | 1305.2 (1051.4–1492.2) | 2749.7 (1372.7–4156.9) |

The present study shows that bronchiolitis hospitalizations caused by infection with RSV among infants younger than two years of age place a significant economic burden on the Colombian healthcare system. Additionally, that the in-patient care costs of infants treated in the PIMC or in the PICU were approximately 5.0–2.5 times greater than those for infants treated in the PW, and that in general, the more severely ill the patient, the greater the percentage of the bill attributable to hotel services (hospital stay), fluids and supplies, and medications, and the lesser the percentage of the bill attributable to medical services and nebulization and oxygen therapy.

The most remarkable result to emerge from the data is that it further enhances the understanding of the impact of RSV by estimating the economic burden of RSV-related bronchiolitis hospitalizations in a middle-income tropical country. This is essential for an accurate assessment of cost-effectiveness studies of current and future interventions for preventing or treating these respiratory infections. Specifically, although not exclusively, our results could serve as an input for models for assessing the cost-effectiveness of both RSV-specific humanized immunoglobulin (palivizumab) and the future RSV vaccines for infants via maternal immunization.12

Our results agree with those reported by Heikkila P. et al., showing a higher proportion of hospital costs driven by the cost of infants aged less than 12 months and by those treated in the PICU in contrast to infants aged more than 12 months and to other inpatients.15 Likewise, our results are in good agreement with those obtained in other recent studies performed in second and third healthcare level hospitals in our country in which it has been reported both that the mean direct cost of infants with bronchiolitis ranged between US$492.0 and US$1492.0, and that the mean LOS was 6.2 (± 0.51 days).16,17 Similarly, in agreement with our findings, studies in the literature have reported proportions of costs in infants requiring admission to the PICU with respect to infants treated in general wards ranging from 1.5 to 4.0, with the greatest proportions among infants aged less than 12 months.15,18 However, we found much lower costs for RSV-related bronchiolitis hospitalizations with respect to those reported in more affluent countries, with these differences being more apparent when studies conducted in the United States were used for comparison.9,15,18–22 The reported mean costs of RSV-related bronchiolitis hospitalizations vary extensively between studies performed in United States, Canada and in the UK, ranging between US$1313.2 and US$50853.0, after conversion into dollars based on official exchange rates. Notably, the observed differences in costs for RSV-related bronchiolitis hospitalizations are present despite a longer mean LOS in our patients, a variable that has been reported as an important determinant of the cost of bronchiolitis hospitalizations.15 The observed differences in costs of RSV-related bronchiolitis hospitalizations between countries likely result from many factors. It has been well described in the literature that variations in healthcare costs between countries with various types of health care systems may be due to several causes, such as the prices of labor, services and goods, including pharmaceuticals, volume of resources, administrative costs, use of high-tech interventions, access to and provision of specialized care instead of primary care, and payment schemes.23,24 Of these, prices of labor and goods, including pharmaceuticals, and administrative costs appeared to be the major drivers of the variation in costs between countries, especially between the United States and other countries.24,25 Our results corroborate the expected international cost differences in hospitalization costs from RSV-related bronchiolitis, and highlight the importance of their accurate estimation in different countries in order to help to allow just allocation of resources within the health care systems of each of these countries.

We are aware that our research may have at least four limitations. The first is that the study took only direct medical costs into consideration. The second is that the study focused only on costs associated with hospitalizations and did not include costs arising before admission or after discharge from hospital, including the subsequent morbidity after RSV infection. Although in-patient care accounts for a high proportion of the total costs of bronchiolitis,15 the exclusion of indirect costs and costs arising after discharge from hospital, could have underestimated the actual costs associated with RSV-related bronchiolitis. The third is that our study was limited to patients hospitalized at a single tertiary care pediatric hospital and our findings could not be generalizable to all bronchiolitis patients. However, the Fundacion Hospital La Misericordia receives patients from the majority and most representative medical insurance companies in the city and the country. The fourth is our inability to calculate marginal increased costs resulting from patients’ moving through hospital services of increasing complexity.

These limitations warrant further research in other hospitals and to take into consideration not only indirect costs, but also the long-term consequences of RSV-bronchiolitis, which in approximately half of the cases comprises recurrent wheezing/asthma symptoms.26 Recurrent wheezing/asthma episodes are responsible for significant use of quick relievers and controller medications and for substantial use of health care resources such as urgent care, emergency department visits, and hospitalizations.27,28 In addition, it is worth mentioning that prophylactic administration of palivizumab has been reported as reducing the risk of recurrent wheezing and asthma.29,30

In conclusion, the present study helps to further our understanding of the economic burden of RSV-related bronchiolitis hospitalizations among infants younger than two years of age in a middle-income tropical country. This is essential for assessment of the cost-effectiveness of interventions to help to ensure the most efficient use of health resources within the Colombian healthcare system and probably that of other similar MICs. Future studies should consider not only the direct medical costs associated with bronchiolitis hospitalizations caused by infection with RSV, but also indirect costs and costs associated with the long-term consequences of RSV-bronchiolitis.

Funding sourcesThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interestNone.

The authors thank Mr. Charlie Barret for his editorial assistance.