Asthma may influence children's health-related quality of life (QoL) differently by various symptoms, at different severity. The primary aim of this study was to evaluate the QoL in children with asthma and describe the impact of each asthma symptom on the child's well-being at different severity levels.

Material and MethodsTwo hundred randomly selected children and one of their parents who consulted an outpatient asthma clinic, participated in the study. Qol was assessed with DISABKIDS-Smiley measure for children aged 4-7 years and with DISABKIDS DCGM-37 and Asthma Module for children 8-14 year old.

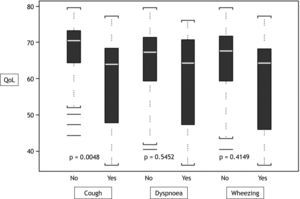

ResultsMost of the children suffered from mild or moderate persistent asthma. Children with uncontrolled asthma stated lower QoL compared to partly controlled or controlled in both age groups (p<0.05 in all domains). Cough appeared to affect QoL of 8-14 year olds more than other symptoms, especially in girls. In younger children, sex (boys, p=0.039), age (p=0.045), proxy sex (father, p=0.048), frequency of doctor visits (4-6 months, p=0.001), use of beta-2 agonists (p=0.007) and father's smoking habits (p=0.015) were associated with the QoL of coughing children but no correlation between cough and QoL was detected. In the 8-14 year age group coughers reported lower QoL compared to their counterparts; moreover, cough was found to affect QoL more than other symptoms (p<0.05 in all domains).

ConclusionsCough has a direct effect on asthmatic children's QoL but there is still an obvious need for research to reveal all the determinats of this effect.

The diagnosis of asthma in children is primarily clinical based upon the presence of a pattern of symptoms such as episodic breathlessness, wheezing, cough, and chest tightness. However, childhood asthma shows remarkable phenotypic variability that results from the heterogeneity of underlying pathophysiologic mechanisms1,2.

Current guidelines for asthma care categorise asthma severity based upon the frequency of asthma symptoms, medication use, and lung function tests. There are several studies showing that asthma severity assessment is not satisfactory in clinical practice. It has been reported that there is a lack of correlation between lung function and symptoms3,4, poor concordance of home spirometry with other indices of disease activity5, as well as limited reproducibility among paediatric asthma specialists in classifying asthma severity6. Furthermore, severity is not an unvarying feature of an individual patient's asthma, as environmental determinants may change and patient's response to treatment may affect clinical presentation2.

The World Health Organization has defined “Quality of Life” (QoL) as “individuals' perceptions of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards and concerns”7. It is a broad ranging concept affected in a complex way by the persons' physical health, psychological state, level of independence, social relationships, personal beliefs and their relationships to salient features of the environment8. The degree to which asthma influences health related QoL, however, depends on multiple factors, among which asthma control is likely to play a central role9–12.

Although no universal definition exists, asthma control is generally considered to reflect disease activity as captured by fluctuations in symptoms and the degree to which these symptoms limit activities, disturb sleep, or require the use of a rescue inhaler13,14. Asthma control and severity are two different but complementary concepts; in routine practice, control appears to have more operational implications15.

It has been reported that there is a stronger association between QoL and asthma symptoms rather than objective tests (spirometry, peak expiratory flow, etc)16. Nevertheless, in the literature there are several studies concerning the effect of asthma symptoms upon QoL but they are mainly focused on severe and uncontrolled asthma and the majority of them focus on the effect of wheezing, dyspnoea and asthma attacks17–20.

Nowadays it is acknowledged that any level of asthma symptoms may have some effect on QoL18. However, asthma severity and control may change over time, asthma phenotype may change by age and the various phenotypes are characterised by different clinical presentation. Asthmatic children may experience periods of different symptoms, and QoL may be impaired differently during each period. Wheezing and cough are the most common daily symptoms but their effect on QoL of children may differ17. The primary aim of this study was to evaluate the QoL in children with asthma and describe the impact of each asthma symptom on the child's well-being at different severity levels.

Materials and MethodsParticipantsTwo hundred children and one of their parents (father or mother) participated in the study. They were divided in two age groups, group A: 4–7years old, group B 8–14years old. All participants consulted the outpatient asthma clinic (Allergy-Pneumonology Department, Penteli Children's Hospital) in a regular follow up visit during the period from March 2005 to October 2007 and they had attended at least three visits for asthma care. The participants were randomly selected with the intention to include an equal number of children in each group.

Asthma severity was defined according to the updated 2006 GINA guidelines which categorize asthma severity into four categories (intermittent; mild persistent; moderate persistent; severe persistent) and define control of asthma manifestations as controlled, partly controlled and uncontrolled2. Asthma severity assessment was based on symptoms, airflow obstruction, response to treatment, and treatment requirements during the last 6months prior to the interview. The level of asthma control was assessed for the 4-week period prior to the interview. Questions regarding daytime symptoms, activity limitations, nocturnal symptoms, quick-relief medications usage, along with questions about hospital care and occurance of exarcebations were included. Spirometry and clinical examination were also performed before the interview.

InstrumentsThe instruments used for the study were the DISABKIDS Chronic Generic Measure — long form (DCGM-37), the DISABKIDS Smiley Measure and the DISABKIDS Condition-specific modules for asthma along with a special form for demographic, asthma treatment, asthma symptoms, home environment, school environment and clinical data.

The DISABKIDS chronic generic module (DCGM-37) consists of 37 Likert-scaled items assigned to six dimensions: Independence, Emotion, Social inclusion, Social exclusion, Limitation, and Treatment. These showed satisfactory internal consistencies of these scales ranging from α = .79 (Social inclusion) to α = .90 (Emotion). These six dimensions can be combined to produce a general score for health-related quality of life (HRQoL)21. DISABKIDS-Smiley measure assesses general quality of life of children between 4 to 7 developmental years. A 5-point scale of smiley faces response scale is used.

The condition specific asthma questionnaire (DISABKIDS Asthma Module) consists of two domains: the impact domain (6 items) concerning limitations and symptoms, and the worry domain (5 items) concerning fears related to asthma. The internal reliability of the impact domain is α = 0.83 and α = 0.84 for the worry domain21–23. Both DISABKIDS self-report versions (child version) and proxy versions (completed by one of their parents) were used.

Data CollectionData was obtained through interviews with children and their parents. After obtaining informed consent from parents and older children, demographic data along with data concerning home and school environment were collected. The next step was to complete the age appropriate DISABKIDS Instruments.

A thorough history concerning asthma symptoms, triggers and treatment was also performed. The ethics committee of Penteli Children's Hospital approved the study protocol.

Statistical analysisIntra-class correlation coefficients (ICC) were computed to assess the degree of agreement in child's QoL scores between children and parents. Scale reliability was measured by Cronbach's α. Shapiro-Wilk test was used to evaluate the normality of all continuous variables (i.e. several scores for sub-scales regarding child's QoL). Student'st-test and Mann–Whitney were used in order to evaluate the association between normally distributed and skewed continuous variables, respectively, with a categorical variable consisting of two groups. Moreover, multivariate analysis was performed using linear regression models to associate QoL with more than one independent predictor. All values which were found to be significant through simple regression analysis were analysed through a multiple regression analysis model. A probability value of 5 % was considered as statistically significant. Continuous variables are presented as mean values and standard deviation while categorical variables are summarised as relative frequencies. Moreover, the association between two continuous variables (i.e., sub-scales scores with age of diagnosis or duration of disease) was examined through the Pearson or Spearman correlation coefficient. All calculations were conducted using SPSS for Windows (v13, SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL).

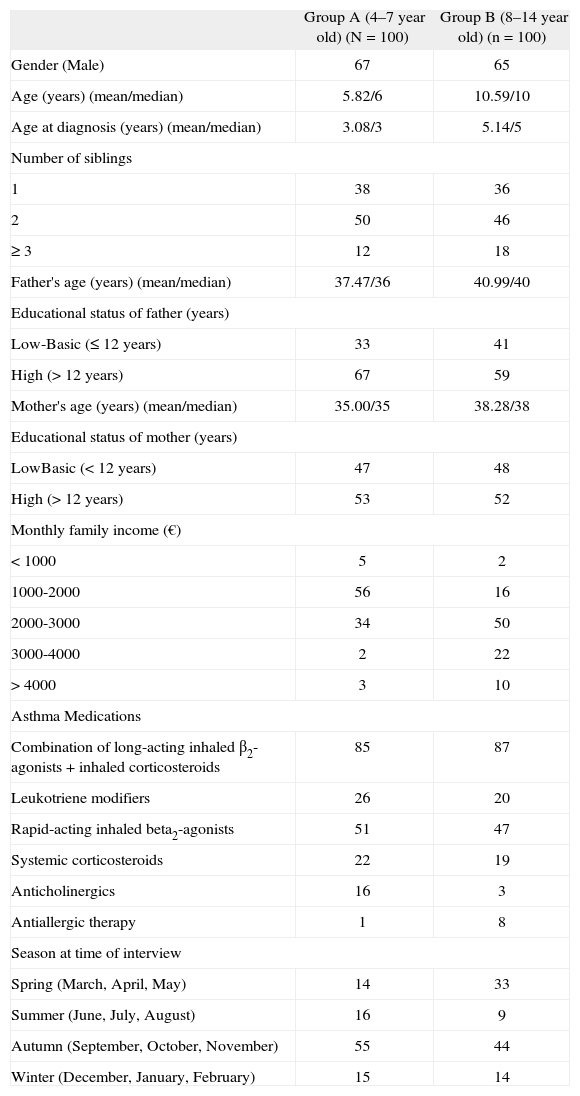

ResultsDescriptive characteristics of participants and their parents for the two age groups are shown in Table I. Most of the interviews were performed during spring and autumn. The vast majority of participants suffered from mild or moderate persistent asthma 84 % (n = 84) and 89 % (N = 89) among children aged 4–7 and 8–14years old, respectively. A combination of long-acting inhaled beta2-agonists and inhaled corticosteroids were the most used controller medications and short-acting inhaled beta2-agonists the most used relievers in both age groups (Table I).

Descriptive characteristics of sample

| Group A (4–7year old) (N = 100) | Group B (8–14year old) (n = 100) | |

| Gender (Male) | 67 | 65 |

| Age (years) (mean/median) | 5.82/6 | 10.59/10 |

| Age at diagnosis (years) (mean/median) | 3.08/3 | 5.14/5 |

| Number of siblings | ||

| 1 | 38 | 36 |

| 2 | 50 | 46 |

| ≥ 3 | 12 | 18 |

| Father's age (years) (mean/median) | 37.47/36 | 40.99/40 |

| Educational status of father (years) | ||

| Low-Basic (≤ 12years) | 33 | 41 |

| High (> 12years) | 67 | 59 |

| Mother's age (years) (mean/median) | 35.00/35 | 38.28/38 |

| Educational status of mother (years) | ||

| LowBasic (< 12years) | 47 | 48 |

| High (> 12years) | 53 | 52 |

| Monthly family income (€) | ||

| < 1000 | 5 | 2 |

| 1000-2000 | 56 | 16 |

| 2000-3000 | 34 | 50 |

| 3000-4000 | 2 | 22 |

| > 4000 | 3 | 10 |

| Asthma Medications | ||

| Combination of long-acting inhaled β2-agonists + inhaled corticosteroids | 85 | 87 |

| Leukotriene modifiers | 26 | 20 |

| Rapid-acting inhaled beta2-agonists | 51 | 47 |

| Systemic corticosteroids | 22 | 19 |

| Anticholinergics | 16 | 3 |

| Antiallergic therapy | 1 | 8 |

| Season at time of interview | ||

| Spring (March, April, May) | 14 | 33 |

| Summer (June, July, August) | 16 | 9 |

| Autumn (September, October, November) | 55 | 44 |

| Winter (December, January, February) | 15 | 14 |

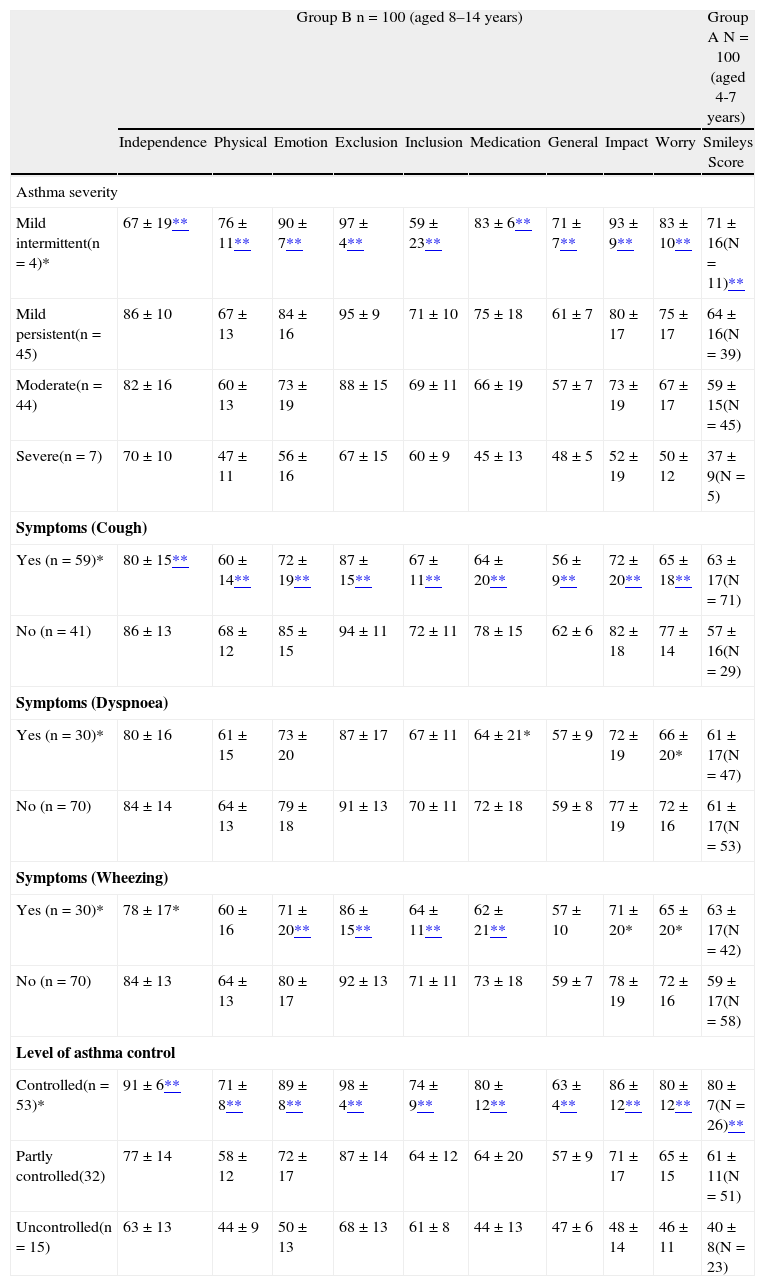

The association of asthma severity, level of asthma control and its symptoms with all subscales indicating the QoL is illustrated in Table II. There is a negative relationship between children's QoL and asthma severity. The level of asthma control directly affects QoL. Children with uncontrolled asthma stated lower QoL in all domains in comparison to children with partly controlled or controlled asthma in both age groups.

The association of asthma severity, asthma control and symptoms with all subscales indicating the quality of life for children (N = 200, 100 aged 4-7years and 100 aged 8-14years)

| Group B n = 100 (aged 8–14years) | Group A N = 100 (aged 4-7years) | |||||||||

| Independence | Physical | Emotion | Exclusion | Inclusion | Medication | General | Impact | Worry | Smileys Score | |

| Asthma severity | ||||||||||

| Mild intermittent(n = 4)* | 67 ± 19** | 76 ± 11** | 90 ± 7** | 97 ± 4** | 59 ± 23** | 83 ± 6** | 71 ± 7** | 93 ± 9** | 83 ± 10** | 71 ± 16(N = 11)** |

| Mild persistent(n = 45) | 86 ± 10 | 67 ± 13 | 84 ± 16 | 95 ± 9 | 71 ± 10 | 75 ± 18 | 61 ± 7 | 80 ± 17 | 75 ± 17 | 64 ± 16(N = 39) |

| Moderate(n = 44) | 82 ± 16 | 60 ± 13 | 73 ± 19 | 88 ± 15 | 69 ± 11 | 66 ± 19 | 57 ± 7 | 73 ± 19 | 67 ± 17 | 59 ± 15(N = 45) |

| Severe(n = 7) | 70 ± 10 | 47 ± 11 | 56 ± 16 | 67 ± 15 | 60 ± 9 | 45 ± 13 | 48 ± 5 | 52 ± 19 | 50 ± 12 | 37 ± 9(N = 5) |

| Symptoms (Cough) | ||||||||||

| Yes (n = 59)* | 80 ± 15** | 60 ± 14** | 72 ± 19** | 87 ± 15** | 67 ± 11** | 64 ± 20** | 56 ± 9** | 72 ± 20** | 65 ± 18** | 63 ± 17(N = 71) |

| No (n = 41) | 86 ± 13 | 68 ± 12 | 85 ± 15 | 94 ± 11 | 72 ± 11 | 78 ± 15 | 62 ± 6 | 82 ± 18 | 77 ± 14 | 57 ± 16(N = 29) |

| Symptoms (Dyspnoea) | ||||||||||

| Yes (n = 30)* | 80 ± 16 | 61 ± 15 | 73 ± 20 | 87 ± 17 | 67 ± 11 | 64 ± 21* | 57 ± 9 | 72 ± 19 | 66 ± 20* | 61 ± 17(N = 47) |

| No (n = 70) | 84 ± 14 | 64 ± 13 | 79 ± 18 | 91 ± 13 | 70 ± 11 | 72 ± 18 | 59 ± 8 | 77 ± 19 | 72 ± 16 | 61 ± 17(N = 53) |

| Symptoms (Wheezing) | ||||||||||

| Yes (n = 30)* | 78 ± 17* | 60 ± 16 | 71 ± 20** | 86 ± 15** | 64 ± 11** | 62 ± 21** | 57 ± 10 | 71 ± 20* | 65 ± 20* | 63 ± 17(N = 42) |

| No (n = 70) | 84 ± 13 | 64 ± 13 | 80 ± 17 | 92 ± 13 | 71 ± 11 | 73 ± 18 | 59 ± 7 | 78 ± 19 | 72 ± 16 | 59 ± 17(N = 58) |

| Level of asthma control | ||||||||||

| Controlled(n = 53)* | 91 ± 6** | 71 ± 8** | 89 ± 8** | 98 ± 4** | 74 ± 9** | 80 ± 12** | 63 ± 4** | 86 ± 12** | 80 ± 12** | 80 ± 7(N = 26)** |

| Partly controlled(32) | 77 ± 14 | 58 ± 12 | 72 ± 17 | 87 ± 14 | 64 ± 12 | 64 ± 20 | 57 ± 9 | 71 ± 17 | 65 ± 15 | 61 ± 11(N = 51) |

| Uncontrolled(n = 15) | 63 ± 13 | 44 ± 9 | 50 ± 13 | 68 ± 13 | 61 ± 8 | 44 ± 13 | 47 ± 6 | 48 ± 14 | 46 ± 11 | 40 ± 8(N = 23) |

The n corresponds to the number of children aged between 8 and 14years old. Never (no) cough or never wheeze means that these symptoms were absent during the last four weeks or that they were rare (less than 2days per week) and they were also characterised by parents and children as not “important” for their Quality of Life.

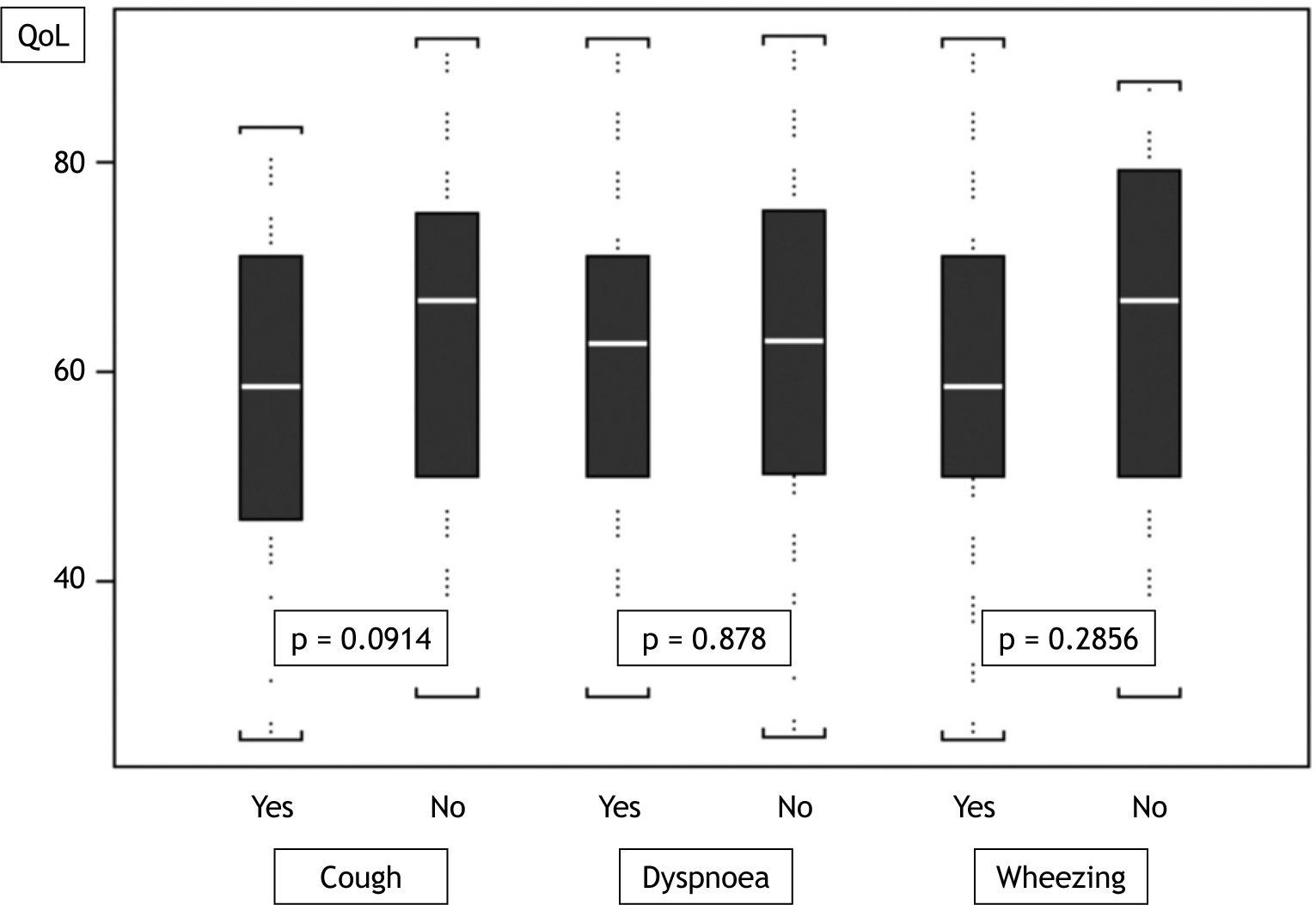

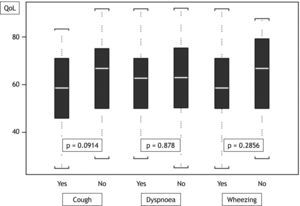

In group A, the difference between the means of QoL scores associated to current respiratory symptoms does not reach any significance (Fig. 1). Nevertheless, statistical analysis revealed that child's sex (boys, p = 0.039), age (p = 0.045), proxy sex (fathers, p = 0.048), frequency of doctor visits (4–6months, p = 0.001), beta-2 agonist usage (p = 0.007) and father's smoking habits (p = 0.015) are significantly associated with the QoL of coughing children.

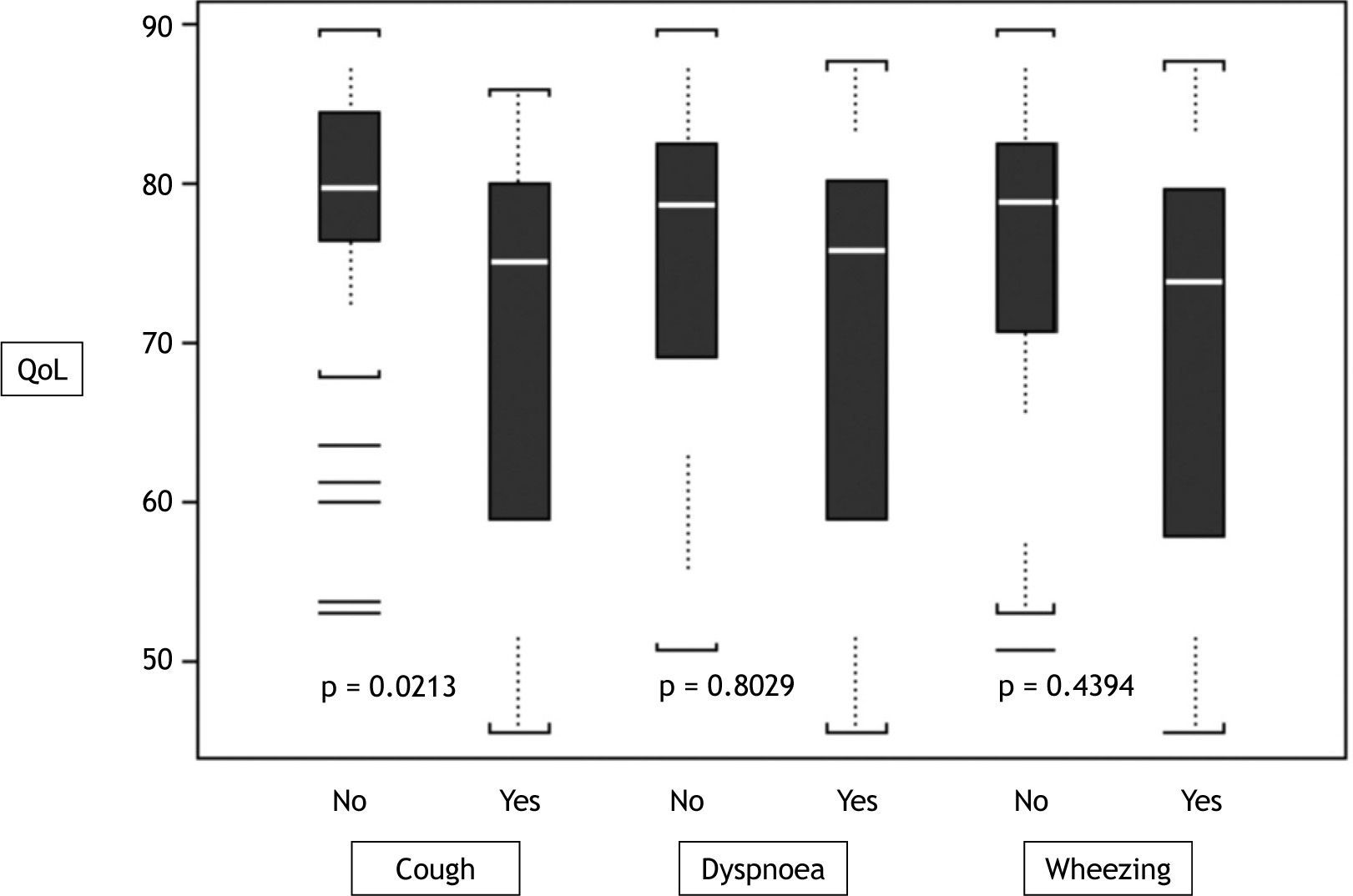

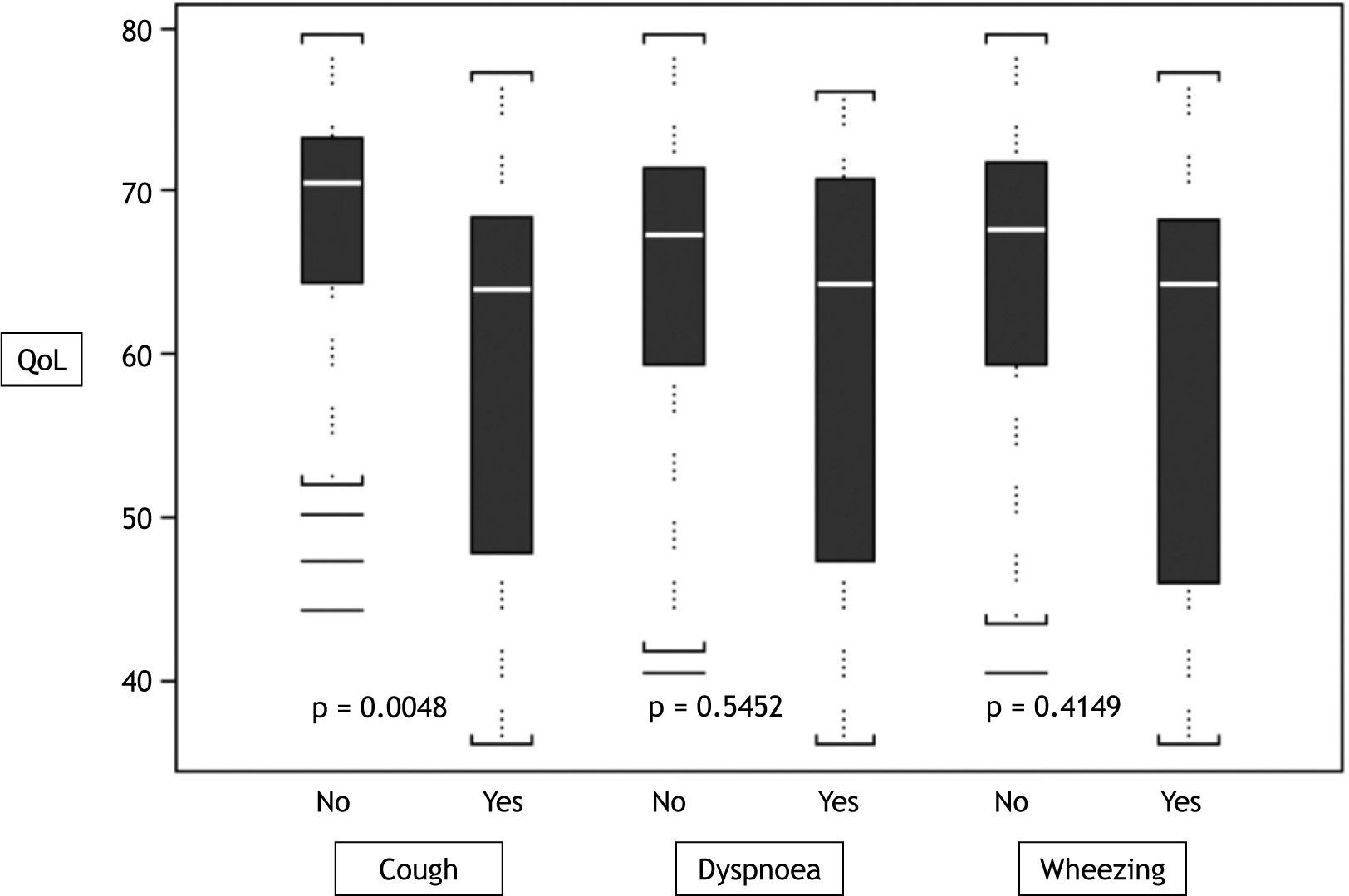

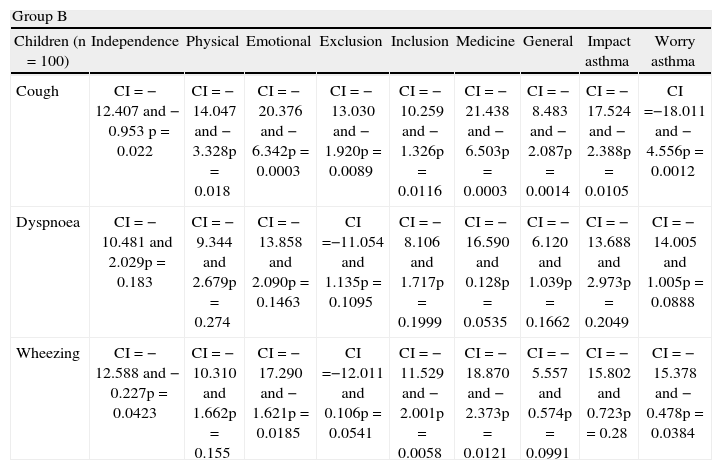

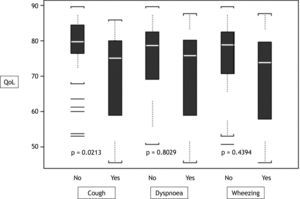

In older children with impaired asthma control QoL scores in the physical, impact, and worry domains are particularly low ( Tables 2 and 3). Current respiratory symptoms are associated with impaired QoL in patients with partly controlled to uncontrolled asthma (p < 0.05 in all domains). Interestingly, cough appears to affect QoL more than other symptoms do (Table III, Figures. 1, 2, 3).

The correlation of cough, dyspnoea and wheezing with the different dimensions of QoL as measured with Disabkids Questionnaire, for children aged 8–14years (n = 100) and their parents

| Group B | |||||||||

| Children (n = 100) | Independence | Physical | Emotional | Exclusion | Inclusion | Medicine | General | Impact asthma | Worry asthma |

| Cough | CI = −12.407 and −0.953 p = 0.022 | CI = −14.047 and −3.328p = 0.018 | CI = −20.376 and −6.342p = 0.0003 | CI = −13.030 and −1.920p = 0.0089 | CI = −10.259 and −1.326p = 0.0116 | CI = −21.438 and −6.503p = 0.0003 | CI = −8.483 and −2.087p = 0.0014 | CI = −17.524 and −2.388p = 0.0105 | CI =−18.011 and −4.556p = 0.0012 |

| Dyspnoea | CI = −10.481 and 2.029p = 0.183 | CI = −9.344 and 2.679p = 0.274 | CI = −13.858 and 2.090p = 0.1463 | CI =−11.054 and 1.135p = 0.1095 | CI = −8.106 and 1.717p = 0.1999 | CI = −16.590 and 0.128p = 0.0535 | CI = −6.120 and 1.039p = 0.1662 | CI = −13.688 and 2.973p = 0.2049 | CI = −14.005 and 1.005p = 0.0888 |

| Wheezing | CI = −12.588 and −0.227p = 0.0423 | CI = −10.310 and 1.662p = 0.155 | CI = −17.290 and −1.621p = 0.0185 | CI =−12.011 and 0.106p = 0.0541 | CI = −11.529 and −2.001p = 0.0058 | CI = −18.870 and −2.373p = 0.0121 | CI = −5.557 and 0.574p = 0.0991 | CI = −15.802 and 0.723p = 0.28 | CI = −15.378 and −0.478p = 0.0384 |

| Parents (n = 100) | Independence | Physical | Emotional | Exclusion | Inclusion | Medicine | General | Impact asthma | Worry asthma |

| Cough | CI = −9.800 and −1.664p = 0.006 | CI = −12.813 and −2.683p = 0.003 | CI = −15.866 and −3.320p = 0.0031 | CI = −11.405 and −2.928p = 0.0011 | CI = −8.062 and −1.005p = 0.0123 | CI = −16.844 and −1.596p = 0.0183 | CI = −11.672 and −3.664p = 0.0003 | CI = −18.413 and −4.003p = 0.0025 | CI = −16.677 and −2.758p = 0.0067 |

| Dyspnoea | CI = −4.745 and 4.285p = 0.9197 | CI = −9.974 and 1.205p = 0.122 | CI = −11.387 and 2.516p = 0.2084 | CI =−7.344 and 2.161p = 0.2819 | CI = −4.003 and 3.741p = 0.9466 | CI = −10.349 and 6.389p = 0.6397 | CI = −7.180 and 1.923p = 0.2546 | CI = −12.011 and 4.004p = 0.2049 | CI = −11.141 and 4.235p = 0.088 |

| Wheezing | CI = −5.932 and 3.080p = 0.5315 | CI = −11.507 and −0.448p = 0.0344 | CI = −15.330 and −1.741p = 0.0143 | −9.657 and −0.307 p = 0.037 | CI = −7.339 and 0.271p = 0.0684 | CI = −12.899 and 3.756p = 0.2787 | CI = −9.612 and −0.685p = 0.0242 | CI = −15.109 and 0.723p = 0.0744 | CI = −15.316 and −0.197p = 0.0444 |

*CI: 95 % Confidence Interval of the Difference; p: p-value

A clear association between cough and QoL was detected in group B. In particular, coughers reported lower QoL compared to their counterparts. Moreover, cough was found to affect QoL more than other symptoms (Tables II and III, Figs. 1 and 2).

Table II describes the association of asthma severity, asthma control and the most common asthmatic symptoms with all subscales indicating the QoL for children aged 8–14years old and smiley score for children 4–7years old. Mean scores ± SD and p-values indicate the correlation of each factor with QoL. Similarly, Table III presents the correlation of cough, dyspnoea and wheezing with the different dimensions of QoL as measured with Disabkids Questionnaire, for children aged 8–14years old and their parents as derived from multiple regression analysis.

A multivariate linear regression analysis and independent two-sample t-test demonstrated a number of factors affecting coughers' QoL. Specifically, QoL as stated by coughing children is significantly correlated with their sex; girls with cough had lower QoL scores than boys in all subscales of QoL and also in asthma specific modules (p = 0.0003-0.017 and p = 0.0145 (impact) and p = 0.038 (worry), respectively). Children who were visiting their doctor at least every 3months or less, stated lower QoL than children visiting their doctor every 4–6months or more (p = 0.003-0.0389). Moreover, coughers stated higher scores in several subscales of QoL when in addition to inhaled corticosteroids they were also on long acting beta-2 agonists [p = 0.009-0.0114 and p = 0.0155 (impact) and p = 0.0088 (worry) for asthma modules].

Proxy reports of QoL were also correlated with children's sex (p = 0.0003-0.0236). Proxy reports for coughing girls stated lower scores of QoL in comparison to boys. Frequency of follow up visits seems to affect QoL. Parents of children with follow up visits every 6months or less stated lower scores of QoL than parents with follow up visits that were less frequent (p = 0.0317-0.0481). On the contrary to children's reports, proxy reports were not correlated with the use of beta-2 agonists (either short or long acting).

We evaluated the level of agreement between parents and children concerning QoL score and a moderate agreement for all subscales, with the exception of general subscale, was noted. In particular, the ICCs range between 0.331 (i.e., inclusion sub-scale) and 0.664 (i.e., impact) and only for general sub-scale the degree of agreement was extremely low (0.179). Moreover, all domains of the scale showed great reliability since Cronbach's alpha was between 0.85 (emotion) to 0.92 (social inclusion).

DiscussionThe present study evaluated the HRQoL of asthmatic children focusing on mild or moderate persistent asthma and described the impact of each asthma symptoms on the child's well-being. A close association between asthma control and QoL in both preschool and schoolchildren was observed. However, the principal finding was that cough affects QoL more than other symptoms do.

A previous study during DISABKIDS questionnaire testing in Greek asthmatic children led to lower Cronbach's alphas in comparison to other European countries due to a small number of participants and the fact that the researched population included mostly exercise-induced asthma, which might result in a different impact on their HRQoL 22. Our study achieved better reliability of the scale since Cronbach's alphas were between 0.85 and 0.92. A Greek study concerning quality of life in children with Cystic Fibrosis (CF) and asthma concluded that the QoL of children with asthma was less affected than that of CF children. Children with CF were more restricted in physical activities, they had more symptoms and their emotional health was more affected, as the negative symptoms dominated. On the contrary, social activities and compliance with the treatment did not differ significantly23.

Most studies concerning QoL in asthmatic children were focused on its severity and the majority deal with severe asthma. A limited number of studies aimed to determine the effect of asthma symptoms on QoL and even fewer on asthmatic children with mild or moderate asthma 17,18. It has been reported that average QoL for patients with mild and moderate persistent asthma is close to population norms. It might be the case that the strong relationship between impaired QoL and more severe asthma does not apply to patients with mild asthma18. According to our data analysis, asthma severity was found to correlate negatively with QoL scores. That was more obvious in asthma specific modules since children with moderate or severe asthma were stated significantly lower scores of impact and worry. Equally, younger children with mild asthma were found to have higher scores of the Smiley measure. Interestingly, a literature review showed that patients with mild asthma often suffer impairment in QoL and use considerable scheduled and unscheduled health care resources25. Plaza et al also reported similar findings concerning QoL in their study on differences in asthma clinical outcomes according to initial severity26.

We found that despite most of our symptomatic patients having few symptoms, they experience significantly poorer QoL than their asymptomatic peers. Mohangoo et al. in a recent study with asthmatic adolescents related wheezing attacks to many areas of HRQoL, stating that the QoL profile of adolescents with wheezing attacks was consistently lower20. In our study cough was found to affect the QoL more than other symptoms did, in both groups. Despite the high incidence of cough observed in clinical practice, little is known about the impact of coughing from the patient perspective, and only few studies have described HRQoL in coughers on the basis of diagnosis27. Therefore, that was a notable finding since health professionals underestimate its effect on child's QoL and follow Szabo & Cserhati's conlusion that even mild symptoms, and even if they are rare, can still affect the quality of the patients' everyday lives28.

We also found that the frequency of follow-ups that are in close relevance with the level of asthma control affect QoL. This is also supported from the effect of duration of treatment on QoL. Children who were under treatment for less than six months and children under treatment for a long period but without a good asthma control or with poor compliance, tend to state lower QoL scores.

On the other hand, asthma is a variable disease. Patients with controlled asthma may experience periods of high morbidity, and QoL may be significantly impaired at this time. Moreover, although asthma control and asthma severity are interrelated, there is an increasing consensus that they reflect different aspects of the disease 13. This was also supported from our findings since children with good asthma control had better QoL scores despite their asthma severity. The impact of asthma on patients' HRQoL is not fully accounted for by objective measures such as lung function. Thus, HRQoL data complement rather than duplicate result from traditional, objective assessments of asthma control29. Additionally, symptom control in bronchial asthma could also be in conflict with quality of life, as many prophylactic measures to prevent exposure to allergens also restrict a patient's life28.

It is recognised that assessment of a patient's HRQoL provides a more accurate estimate of the burden of disease and additionally represents a formal and validated part of the history30. Successful treatment of a child with asthma should achieve benefit for children and families overall QoL and functioning, as well as improvement in objective symptoms and clinical parameters. As asthma is a main reason for patient hospitalisation and influences children's QoL, there is area for possible interventions to improve children's and family's QoL through different ways31.

When patients with partly controlled or uncontrolled asthma have symptoms, their relative QoL is significantly affected despite the fact that when they are symptom-free, QoL is as good as the average for the general population. This may contribute to our understanding of why many patients appear to respond to asthma only on an episodic basis, and find it difficult to follow long-term treatment18. Additionally, an understanding of variations in QoL among patients with moderate asthma control may be important for our understanding of factors influencing the use of health services and also help health professionals to take a careful, thorough history and take even mild symptoms into consideration, since their effect may be underestimated.

An important point indicating cultural effect was that ICCs for children and their proxies reports were high and furthermore a zero convergence was found between child and parent report with respect to the emotional and social scale. During a study for cross-cultural validity of the DISABKIDS generic quality of life instrument was found that Greek parents did not experience stigma and the cultural effect was quite high, especially regarding the importance of the extended family in Greece, and the impact of this32.

Limitations concerning instruments include excess time-consumption for DISABKIDS Chronic Generic Measure – long form (DCGM-37) and DISABKIDS Asthma Module due to its length. On the other hand DISABKIDS-Smiley measure is brief and easy to complete but it can only assess the general quality of life of children between 4 to 7 developmental years and not disease specific QoL. Nevertheless, both instruments can be used in order to compare asthmatic children with healthy or children with other chronic diseases.

ConclusionsAsthma is a disease with a great variety concerning clinical outcome and that means that there are no “gold standards” concerning its treatment. Therefore, QoL could be used as a good measure of treatment approach. Even though cough is a common symptom to childhood asthma, its effect on QoL seems to be direct. Our study revealed a number of factors that are correlated with impaired QoL in children with cough and asthma. There is, however, an obvious need for research in order to reveal all the determinats of this effect.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

The DISABKIDS project was supported by the European Commission (QLG5-CT-2000-00716) within the Fifth Framework Program “Quality of Life and Management of Living Resources”. The European Union has granted this project for the development of a modular questionnaire to assess health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in children and adolescents with chronic health conditions.