In the present study, we reviewed 44 cases of disseminated BCG infection during a 10-year period in an Iranian referral children medical centre hospital.

Material and methodsIn this study, all of the patients with clinical and laboratory findings that were compatible with a diagnosis of disseminated BCG were included.

ResultsThrough 10 years evaluation, 44 patients were found with disseminated BCG disease. Hepatomegaly and splenomegaly were seen in 68% and 66% of patients, respectively. Osteomyelitis was observed in 9% of our cases. Decrease in blood cells including anaemia, leucopoenia, neutropenia and thrombocytopenia were associated with more severe disease and even deaths. Moreover, 80% and 70% of patients who died had high level of C reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR). Among the dead patients, 80% had abnormal sonography. Thirty nine percent of patients had immunodeficiency, while more than half of the patients who died had no identified immunodeficiency.

ConclusionThese findings confirm the need to do sonography as well as bone imaging immediately in all patients with BCGitis. Assessment of the inflammatory factors in order to predict the prognosis of the disease is recommended. Furthermore, complete blood count would provide important information and should perform in all patients with BCGitis.

Bacille Calmette–Guérin (BCG) vaccine is administered broadly to prevent tuberculosis especially miliary and meningeal tuberculosis in childhood. In Iran, all newborn babies are given BCG substrain Pasteur vaccinations at birth. Although this vaccination exhibits good protective efficacy, some complications with different severity, ranging from a regional-localised disease or BCGitis to a more severe life-threatening disseminated form or BCGosis may occur.1

Disseminated BCG has almost occurred in immunised persons with underlying congenital or acquired immunodeficiency disorders such as severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID), chronic granulomatous disease (CGD) and infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).2,3

A disseminated infection is considered as a rare complication due to BCG vaccination and the rate of this complication has increased up 0–1/100,000 vaccinated children in recent years.4 This infection mainly depends on the host immune system, and patients with cellular immunodeficiency are at the greatest risk.5 However, in half of the children, the immune system of the host has no defect and the cause of the BCGitis is idiopathic.6

It has been reported that interferon gamma (IFN-γ), a cytokine produced by T-cells and NK-cells in response to IL12/23 stimulation, plays an important role in defending against BCG infections.1 Defect in IFN-γ or IL12/23 receptors or signal transduction pathways would lead to incomplete response to mycobacterial infections. In addition, SCID patients and those with Mendelian susceptibility to mycobacterial diseases might develop supreme disseminated complications to BCG, due to bearing deficiency in these pathways.1

In this study, we reviewed 44 cases of disseminated BCG infection during 10 years period in an Iranian referral children medical centre (CMC) hospital.

Materials and methodsThis was a retrospective study through a 10-year period from 2001 to 2011 on children who developed disseminated BCG after vaccination in CMC Hospital.

In this study, all of the patients with clinical and laboratory findings compatible with a diagnosis of disseminated BCG were included. Inclusion criteria for patients were lymphadenitis, abscesses or fistula in the site of BCG vaccination or another site or BCG ulceration with two or more signs and symptoms of a systemic syndrome compatible with mycobacterial disease, including fever >38°C more than two weeks, weight loss, recurrent or persistent diarrhoea, related parents, family history of immunodeficiency, recurrent or persistent oral candidiasis, pneumonia, osteomyelitis, anaemia (Hb<10), hepatomegaly and splenomegaly.

In addition, evidence of BCG infection was confirmed by histopathological findings of acid-fast bacilli at two or more anatomic sites beyond the region of vaccination.7

Statistical analyses between the two groups were performed using SPSS 16 software. Fisher exact test and independent test were used to analyse the data and P≤0.05 was considered statistically significant.

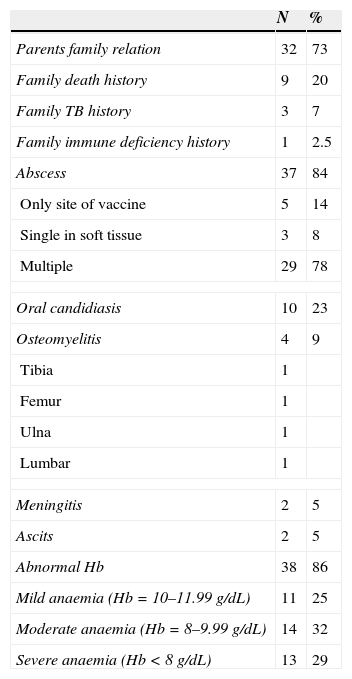

ResultsIn this study, through 10 years evaluation, 44 patients were found with disseminated BCG disease, with an age range between 1.5 month and 4.8 years and mean age of 13.7±13.3 years old. The average interval between vaccination and complications was 2.9±1.7 month (range 1 month to 8 months). The male to female ratio was 1.3:1. Clinical features of the patients are depicted in Table 1.

Summary of data on 44 cases of disseminated BCG disease.

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Parents family relation | 32 | 73 |

| Family death history | 9 | 20 |

| Family TB history | 3 | 7 |

| Family immune deficiency history | 1 | 2.5 |

| Abscess | 37 | 84 |

| Only site of vaccine | 5 | 14 |

| Single in soft tissue | 3 | 8 |

| Multiple | 29 | 78 |

| Oral candidiasis | 10 | 23 |

| Osteomyelitis | 4 | 9 |

| Tibia | 1 | |

| Femur | 1 | |

| Ulna | 1 | |

| Lumbar | 1 | |

| Meningitis | 2 | 5 |

| Ascits | 2 | 5 |

| Abnormal Hb | 38 | 86 |

| Mild anaemia (Hb=10–11.99g/dL) | 11 | 25 |

| Moderate anaemia (Hb=8–9.99g/dL) | 14 | 32 |

| Severe anaemia (Hb<8g/dL) | 13 | 29 |

Lymphadenitis was seen in 38 patients (86%) and abscess at the injection site was reported in 37 cases (84%). Among patients, five had single abscess at the site of vaccine, three had single abscess in the soft tissue and 29 cases had multiple abscesses in different sites. Osteomyelitis was observed in four cases (9%). Twelve patients (27%) and 10 cases (22%) suffered from pneumonia and oral candidiasis, respectively (Table 1).

Meningitis was seen in two cases (4.5%). Fever was found in 26 cases (59%) and tuberculin skin test was positive in 34 (77%) children. Acid-fast bacilli were positive in the direct smear of all patients, and the results of all blood and bone marrow cultures were negative.

Weight loss and cutaneous complications due to BCG vaccination were found in 28 (64%) and 15 (34%) patients, respectively.

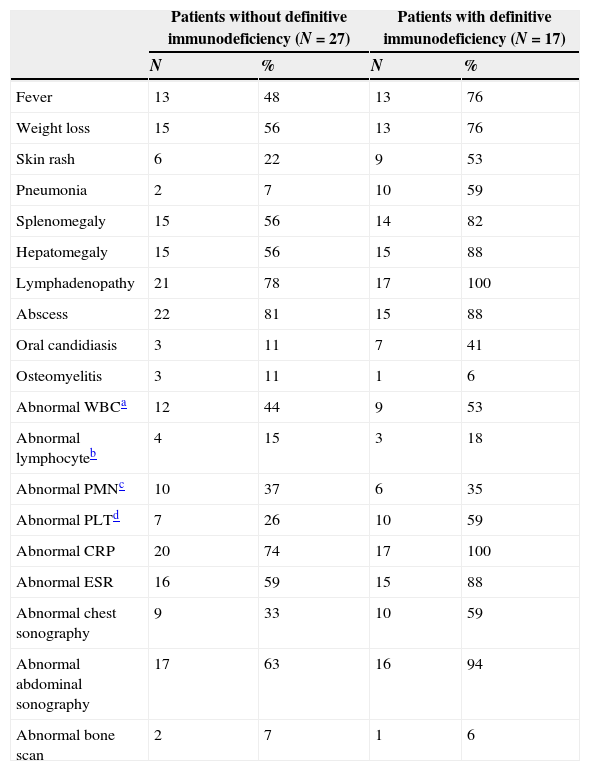

Laboratory investigations in the patients with disseminated BCG are shown in Table 2. Abnormal white blood cells were found in 21 patients (48%) including nine cases with leucopoenia and 12 cases with leucocytosis.

Clinical, laboratory and imaging findings in patients with disseminated BCG disease.

| Patients without definitive immunodeficiency (N=27) | Patients with definitive immunodeficiency (N=17) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |

| Fever | 13 | 48 | 13 | 76 |

| Weight loss | 15 | 56 | 13 | 76 |

| Skin rash | 6 | 22 | 9 | 53 |

| Pneumonia | 2 | 7 | 10 | 59 |

| Splenomegaly | 15 | 56 | 14 | 82 |

| Hepatomegaly | 15 | 56 | 15 | 88 |

| Lymphadenopathy | 21 | 78 | 17 | 100 |

| Abscess | 22 | 81 | 15 | 88 |

| Oral candidiasis | 3 | 11 | 7 | 41 |

| Osteomyelitis | 3 | 11 | 1 | 6 |

| Abnormal WBCa | 12 | 44 | 9 | 53 |

| Abnormal lymphocyteb | 4 | 15 | 3 | 18 |

| Abnormal PMNc | 10 | 37 | 6 | 35 |

| Abnormal PLTd | 7 | 26 | 10 | 59 |

| Abnormal CRP | 20 | 74 | 17 | 100 |

| Abnormal ESR | 16 | 59 | 15 | 88 |

| Abnormal chest sonography | 9 | 33 | 10 | 59 |

| Abnormal abdominal sonography | 17 | 63 | 16 | 94 |

| Abnormal bone scan | 2 | 7 | 1 | 6 |

Definitive immunodeficiency was detected in 17 children (39%) with disseminated BCG infection including: SCID in five cases (11%), T cell deficiency in six cases (14%), CGD in five cases (11%) and HIV in one case (2%).

Among SCID and T cell deficiency cases, three (60%) and one (16%) case died, respectively. The parents of 32 cases (73%) were consanguine and 13 patients (81%) with consanguine parents died.

Chest radiography was performed in 42 patients and among them 19 cases (45.2%) had abnormal results including perihilar infiltration, reticular infiltrates or pleural effusion.

Abdominal sonography was performed in 43 patients and 33 cases had abnormal findings. Hepatomegaly and lymphadenopathy was observed in 14 patients (33%) and three cases (7%), respectively. Concurrent hepatosplenomegaly with lymphadenopathy was observed in 10 cases (23%) while one patient had splenomegaly with lymphadenopathy at the time of admission.

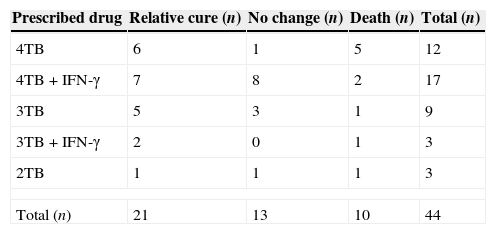

All patients received at least two anti TB medications (isonaizid, rifampicin, ethambutol and streptomycin). Meanwhile in 20 cases, in addition to the above anti TB regimens, IFN-γ was started at a dose of 50μg/m2 (Table 3).

The anti TB medication for all patients with disseminated bacilli Calmette–Guerin disease.

| Prescribed drug | Relative cure (n) | No change (n) | Death (n) | Total (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4TB | 6 | 1 | 5 | 12 |

| 4TB+IFN-γ | 7 | 8 | 2 | 17 |

| 3TB | 5 | 3 | 1 | 9 |

| 3TB+IFN-γ | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| 2TB | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Total (n) | 21 | 13 | 10 | 44 |

4TB=isonaizid, rifampicin, ethambutol and streptomycin, 3TB=isonaizid, rifampicin and ethambutol, 2TB=isonaizid and rifampicin.

Among all patients, 10 (23%) cases died. In this study there was no significant relation between underlying immunodeficiencies and death (P value=0.7).

DiscussionAlthough immunisation of children with BCG is recommended by the World Health Organization in communities with a high prevalence of tuberculosis,7,8 occurrence of several complications range from local inflammatory reactions to disseminated diseases and even deaths associated with the vaccine is probable.9

We found that disseminated BCG are more common in boys, which is in contrast to the study of Deeks et al. in Canada during 2005 that reported slightly higher incidence of disseminated BCG in girls.10 In our study lymphadenopathy was detected in 86% of patients, which was similar to other reports.6,11 Prevalence of fever, rash and cachexia in our study was less than Casanova et al. reported; this could be due to differences in the sample size.6

The rate of mortality and morbidity among children with disseminated BCG in this study was 23%; this was lower than other reports.4,12

In this study among six SCID patients, three (60%) died while all CGD patients, as well as one case with HIV responded to the treatment. In addition, more than half of the patients who died in this study had no identified immunodeficiency. According to the reports of 28 cases with definite disseminated BCG disease in 13 countries, among 20 patients who died due to disseminated BCG disease, all had an immune defect while no mortality was recorded in patients without an identified immunodeficiency.13 In the study of Afshar Paiman, et al., most of their patients died despite aggressive management.7

Oral candidiasis was seen in 23% of patients, which is substantially different to that reported by Sadeghi-Shanbestari et al.4 This could be due to less accurate mouth examination of the patients to find oral candidiasis.

Osteomyelitis was observed in 9% of our cases. Although osteomyelitis is considered as a rare complication,14 clinical suspicion as well as early diagnosis even in the absence of local bone symptoms by using an image are crucial to the effective management of this disease.

Hepatomegaly and splenomegaly were seen in 68% and 66% of patients, respectively, which is consistent with other reports.11,15

In this study, two patients had meningitis and both of them died. Meningitis is considered as a severe and fatal complication caused after BCG vaccination.

In our study, 86% of patients had anaemia, with 32% and 29% of them having moderate and severe anaemia, respectively. Among the 10 patients who died, seven had Hb<10 with moderate or severe anaemia (P<0.05). Therefore, not only is anaemia (Hb<10) one of the main criteria for BCGitis diagnosis,4 but the severity of anaemia could also be considered as prognostic factors.

On the other hand, 80% and 70% of patients who died had high level of CRP and ESR. Hence, assessment of these two inflammatory factors in order to predict the prognosis of the disease is recommended.

The results of all blood and bone marrow cultures were negative, consequently, requesting these tests to make decisions for initiation of treatment is not necessary.

According to this study, decrease in blood cell counts (e.g., anaemia, leucopoenia, neutropenia and thrombocytopenia) was associated with more severe disease and even deaths. The mortality rate in patients with thrombocytopenia and neutropenia was significantly higher than the patients (P<0.02 and P<0.03, respectively). In addition, this rate in patients with leucopoenia was significantly higher than cases with normal leucocyte or leucocytosis (P<0.004).

The level of haemoglobin, platelet count, abnormal leucocyte and neutrophils, could be considered as a major criterion for severe disease in patients with BCGitis. Thus, complete blood count (CBC) would provide important information and CBC should be performed in all patients with BCGitis.

On the other hand, among dead patients, 80% had abnormal sonography. These findings confirm the need to carry out sonography as soon as possible in all patients with BCGitis in order to discover organomegaly as well as preventing adverse consequences.

However, the osteomyelitis symptoms due to BCG vaccination could be non-specific, bone imaging is recommended in all patients with BCGitis even in the absence of local bone symptoms.

In this study, 73% of patients had related parents which is compatible with other reports conducted in Iran.4,7 Regarding the high percentage of consanguinity in many Iranian families, BCG vaccination could be done after screening tests have ruled out underlying immunodeficiencies.

In our study, 38.5% of patients had immunodeficiency. It has been reported that BCG vaccine in individuals with healthy immune systems is almost safe and in patients with suppressed immune systems can cause fatal infections.6,13,16,17

It seems that IFN-γ is obligatory for efficient immune response to Mycobacterial species. In addition, IL12/23 axis play an important role for promotion of a competent IFN-γ secretion.18,19 Since BCGitis largely depends on the host immune system, occurrence of BCGitis in more than 60% of patients with normal immune systems seems very improbable. Therefore, more detailed investigation of these genetic defects is required, including different types of mutations which lead to a defect in IFN-γ or IL12/23 receptors or signal transduction pathways.

On the basis of the findings obtained from this study in all children, not only children with known immunodeficiency, disseminated BCG disease after vaccination should be considered.

Moreover, administration of BCG vaccine should avoid at birth those with family history of immunodeficiency or recurrent infection.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the responsible Clinical Research Ethics Committee and in accordance with those of the World Medical Association and the Helsinki Declaration.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data and that all the patients included in the study have received sufficient.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects mentioned in the article. The author for correspondence is in possession of this document.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.