There are a number of clinical scores for bronchiolitis but none of them are firmly recommended in the guidelines.

MethodWe designed a study to compare two scales of bronchiolitis (ESBA and Wood Downes Ferres) and determine which of them better predicts the severity. A multicentre prospective study with patients <12 months with acute bronchiolitis was conducted. Each patient was assessed with the two scales when admission was decided. We created a new variable “severe condition” to determine whether one scale afforded better discrimination of severity. A diagnostic test analysis of sensitivity and specificity was made, with a comparison of the AUC. Based on the optimum cut-off points of the ROC curves for classifying bronchiolitis as severe we calculated new Se, Sp, LR+ and LR− for each scale in our sample.

Results201 patients were included, 66.7% males and median age 2.3 months (IQR=1.3–4.4). Thirteen patients suffered bronchiolitis considered to be severe, according to the variable severe condition. ESBA showed a Se=3.6%, Sp=98.1%, and WDF showed Se=46.2% and Sp=91.5%.

The difference between the two AUC for each scale was 0.02 (95%CI: 0.01–0.15), p=0.72. With new cut-off points we could increase Se and Sp for ESBA: Se=84.6%, Sp=78.7%, and WDF showed Se=92.3% and Sp=54.8%; with higher LR.

ConclusionsNone of the scales studied was considered optimum for assessing our patients. With new cut-off points, the scales increased the ability to classify severe infants. New validation studies are needed to prove these new cut-off points.

Acute bronchiolitis (AB) is the most common lower airway infection in infants, with an annual incidence of 10% in infants under 12 months of age and a hospital admission rate in Spain of between 2 and 5% of all affected patients.1,2 During the epidemic periods, AB constitutes an important healthcare burden in both the primary care and hospital settings.3 Overall, AB is estimated to be the most frequent cause of admission in infants less than one year of age.4 During the 1980s and 1990s, hospital admissions due to AB increased 2.4-fold in the United States,5 with no evidence of increased mortality. At that time, it was suggested that some of these admissions might be unnecessary and could be attributable to other factors.6 Later, in the period between 2000 and 2009, admissions due to AB in infants under 12 months of age began to decrease slightly, although the hospitalisation costs increased by 34%, at the expense of the more serious cases requiring admission to intensive care and mechanical ventilation.4

Adequate assessment of the clinical condition of a patient with AB is of great importance for the paediatrician, since it constitutes the basis of the decision-making process. Severity scales, applied objectively and with rigour, should prove useful in evaluating the clinical course of the patients and the efficacy of the prescribed treatments. While such scales are routinely used, they are supported by observational studies with limitations; as a result, no concrete scale is recommended in the clinical practice guides.7–9

One of the most widely-used scales in our setting, the Wood–Downes–Ferrés score (WDF), was designed to assess respiratory failure in patients with severe asthma.10,11 However, a Spanish group has recently proposed a new scale, known as the Acute Bronchiolitis Severity Scale (Escala de Severidad de la Bronquiolitis Aguda, ESBA), based on different clinical parameters specific of AB and which has been evaluated in infants under one year of age, with good interobserver agreement.12

The main objective of this study is to determine whether the ESBA shows a better correlation to the severity of AB than the WDF. As secondary objectives, an analysis is made of the mean stay due to bronchiolitis, admission to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU), the need for ventilation, and the incidence of respiratory acidosis.

Material and methodsStudy designA prospective observational study was carried out, involving the consecutive inclusion of all patients ≤12 months of age admitted due to acute bronchiolitis (McConnochie criteria modified by age) between October 2014 and April 2015 to five second-level hospitals (according to the classification of the World Health Organisation)13 in La Comunidad Valenciana and Castilla la Mancha, in Spain. All the patients in the paediatric ward were visited on a daily basis, with application of the admission and discharge criteria contemplated by the AB clinical practice guide of the Spanish Ministry of Health. None of the five hospitals had an ICU of their own; the most seriously ill patients therefore could be transferred to another centre at some point during the clinical course of the disease. Patients with background diseases such as cystic fibrosis, bronchopulmonary dysplasia or congenital heart disease with haemodynamic alterations were excluded, as were infants with hypotonus (Down syndrome, neuromuscular disorders, Prader–Willi syndrome), patients admitted for reasons other than AB, premature infants (<35 weeks of gestation, representing the limit of preventive treatment with palivizumab in our setting), or bacterial superinfection suspected from the clinical or laboratory test findings.

Data collectionThe investigators conducted a structured interview of the parents or legal tutors to collect information referred to the demographic parameters, environmental characteristics, duration of the symptoms and details of the acute disease. A comprehensive review was made to establish the parameters defining increased severity of bronchiolitis, and these were used as the study variables. In addition, the vital signs were recorded, including respiratory frequency and heart rate, as well as oxygen saturation, and a physical examination was carried out with special attention to signs of breathing difficulty and respiratory auscultation. At the time of patient admission, we assessed severity using the two study scales (ESBA and WDF). These instruments regard bronchiolitis as severe when the score exceeds 9 and 7 for the ESBA and WDF, respectively (Annex 1). Scoring was performed by a paediatrician with experience in AB, with the patient naked, awake, calm, without crying or fever, and at least two hours after having received any kind of inhaled medication. The diagnostic and therapeutic procedures during admission (need for intravenous fluid therapy, oxygen therapy, catheter feeding, blood tests, chest X-rays and other complementary tests) were recorded. The scales were applied again in the event of clinical worsening requiring major changes in patient management. Such major changes were defined as transfer to the ICU, the need for mechanical or non-invasive ventilation, parenteral or enteral (tube) nutrition, and the need for oxygen therapy (if not previously required). In such situations, the highest measure recorded was considered for the study.

In order to determine whether a given scale afforded better discrimination of the seriously ill patients, we established a new variable (“severe condition”) that was taken to be positive when the patient experienced at least one of the following conditions: respiratory acidosis with capillary or arterial blood gas analysis (pH<7.35 and pCO2>45mmHg), transfer to the ICU (according to the criteria of the AB clinical practice guide of the Spanish Ministry of Health),8 and mechanical or non-invasive ventilation (continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) and high-flow oxygen (HFO) therapy). This new variable was regarded as the primary study endpoint, used to evaluate the relationship between the scales and the severity of the disease.

Ethical particularsWritten informed consent was requested from the parents or legal tutors before inclusion of the patients in the study. Reporting and disclosure of the personal information of all the participating subjects was regulated by Organic Law 15/1999, of 13 December, referred to personal data protection. The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee at each site.

Statistical analysisThe Epidat 3.0 application was used for the calculation of the sample size. Estimating a proportion of 12% of patients hospitalised due to severe bronchiolitis, with a sensitivity and specificity for the ESBA scale of 96% and 98%, respectively (data supplied by the authors), and a precision of 90%, the required sample size was 123 patients. A loss rate of 10% was assumed.

Categorical variables were reported as absolute and relative frequencies (percentages), while quantitative variables were reported as the mean and standard deviation (SD). Those variables lacking a normal distribution were reported as the median and interquartile range (IQR). Bivariate comparisons were made using the chi-squared test for qualitative variables and the Student t-test for quantitative variables. The Mann–Whitney U-test was applied in the case of variables with a non-normal distribution as confirmed by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test.

We used a weighted kappa coefficient to assess the agreement among the scales.

An analysis was made of diagnostic test sensitivity (Se) and specificity (Sp), with determination of the positive (PPV) and negative predictive values (NPV) of the ESBA and WDF scale according to the variable “severe condition” (using the cut-off points described by the authors in the studies describing the scales), together with the positive (LR+) and negative likelihood ratios (LR−). We subsequently plotted the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves, with calculation of the area under the curve (AUC) and comparison of the ROC curves of the ESBA scale versus those of the WDF scale. The MedCalc application was used for this purpose, and the scales were compared to establish possible differences between them, using the Hanley and McNeil statistical test.

Based on the optimum cut-off points of the ROC curves for classifying bronchiolitis as severe (afforded by the Youden index), we again calculated Se, Sp, PPV, NPV, LR+ and LR− for each of the scales.

Data analysis was carried out using the SPSS version 21 statistical package. The Caspe network calculators (assessment of diagnostic tests), updated in 2015,14 were used for the analysis of sensitivity.

ResultsThe study included a total of 201 patients, of whom 134 (66.7%) were males. Eight infants were excluded from the study: one male with Down's syndrome, three patients whose informed consent was not obtained, three premature infants with a gestational age of <35 weeks, and one infant with clinical manifestations consistent with serious systemic bacterial infection.

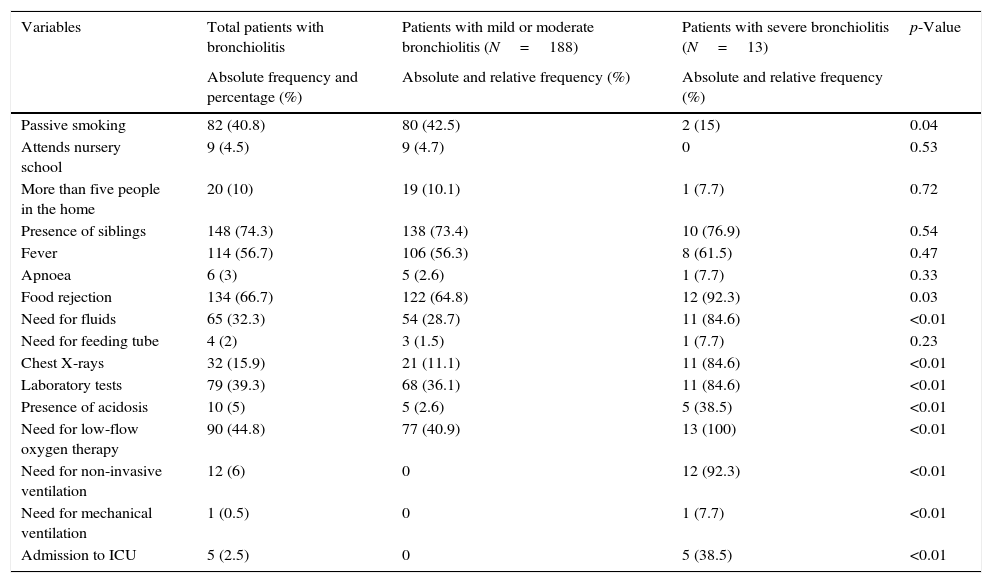

The epidemiological and clinical characteristics of the study sample are described in Table 1. The median patient age was 2.3 months (IQR=1.3–4.4), and the median maternal age was 31 years (IQR=26.7–35). The mean duration of the disease at the time of admission was 2.3 SD2.6 days.

Comparison of the epidemiological and clinical characteristics of the patients with acute bronchiolitis according to severity.

| Variables | Total patients with bronchiolitis | Patients with mild or moderate bronchiolitis (N=188) | Patients with severe bronchiolitis (N=13) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute frequency and percentage (%) | Absolute and relative frequency (%) | Absolute and relative frequency (%) | ||

| Passive smoking | 82 (40.8) | 80 (42.5) | 2 (15) | 0.04 |

| Attends nursery school | 9 (4.5) | 9 (4.7) | 0 | 0.53 |

| More than five people in the home | 20 (10) | 19 (10.1) | 1 (7.7) | 0.72 |

| Presence of siblings | 148 (74.3) | 138 (73.4) | 10 (76.9) | 0.54 |

| Fever | 114 (56.7) | 106 (56.3) | 8 (61.5) | 0.47 |

| Apnoea | 6 (3) | 5 (2.6) | 1 (7.7) | 0.33 |

| Food rejection | 134 (66.7) | 122 (64.8) | 12 (92.3) | 0.03 |

| Need for fluids | 65 (32.3) | 54 (28.7) | 11 (84.6) | <0.01 |

| Need for feeding tube | 4 (2) | 3 (1.5) | 1 (7.7) | 0.23 |

| Chest X-rays | 32 (15.9) | 21 (11.1) | 11 (84.6) | <0.01 |

| Laboratory tests | 79 (39.3) | 68 (36.1) | 11 (84.6) | <0.01 |

| Presence of acidosis | 10 (5) | 5 (2.6) | 5 (38.5) | <0.01 |

| Need for low-flow oxygen therapy | 90 (44.8) | 77 (40.9) | 13 (100) | <0.01 |

| Need for non-invasive ventilation | 12 (6) | 0 | 12 (92.3) | <0.01 |

| Need for mechanical ventilation | 1 (0.5) | 0 | 1 (7.7) | <0.01 |

| Admission to ICU | 5 (2.5) | 0 | 5 (38.5) | <0.01 |

| Median and interquartile range (IQR) | Median and interquartile range (IQR) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age upon admission | 2.4 (1.4–4.5) | 1.1 (0.4–1.6) | 0.01 |

| Median maternal age | 32 (27–35) | 28 (22–30) | 0.12 |

| Number of siblings | 1 (0–1) | 1 (0.5–1.5) | 0.75 |

| Mean and standard deviation (SD) | Mean and standard deviation (SD) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Days of hospital stay | 4.1 (1.9) | 6.1 (3.3) | <0.01 |

Thirteen patients suffered bronchiolitis considered to be severe according to the variable severe condition. The mean WDF score was 5.45 SD1.69 points, versus 5.07±2.18 points in the case of the ESBA. Three patients in our sample (1.5%) scored above 9 points on the ESBA, and 22 (10.9%) scored above 7 points on the WDF. The mean patient stay was 4.30 SD 2.14 days. The results of the bivariate analysis are shown in Table 2.

According to the defining criteria used (see Material and methods), a total of 13 cases were regarded as corresponding to severe AB. The median age of these patients was 1.1 months (IQR=0.4–1.6), which was significantly younger than the median age of the rest of the patients in the sample. In these infants with severe bronchiolitis the WDF and ESBA scores were significantly higher than in the rest of the patients. The mean of WDF score for non-severe bronchiolitis was 5.32 SD1.60 and for severe 7.31±1.88, p<0.01. For the ESBA score: non-severe bronchiolitis was 4.91 SD2.11 and for severe 7.31SD 1.88, p<0.01.

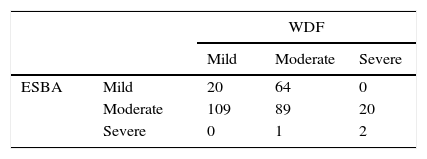

We measured the agreement among scales creating a matrix in which the columns represent the different levels of severity (mild, moderate, severe) as Table 2 shows. We obtained a weighted kappa coefficient of −0.17.

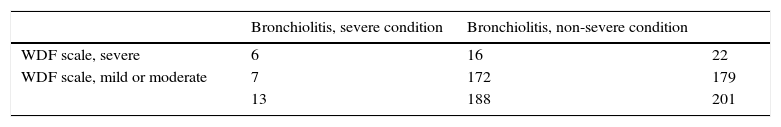

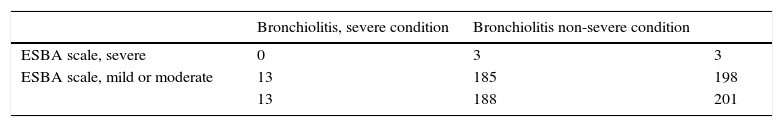

Tables 3 and 4 show the data corresponding to the sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV and likelihood ratios of the scales, according to the cut-off points in the original studies.

Analysis of sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV and likelihood ratios of the cases of bronchiolitis in reference to the WDF scale.

| Bronchiolitis, severe condition | Bronchiolitis, non-severe condition | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| WDF scale, severe | 6 | 16 | 22 |

| WDF scale, mild or moderate | 7 | 172 | 179 |

| 13 | 188 | 201 |

| 95% confidence interval | ||

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | 46.2% | 23.2–70.9 |

| Specificity | 91.5% | 86.6–94.7 |

| PPV | 27.3% | 13.2–48.2 |

| NPV | 96.1% | 92.1–98.1 |

| LR+ | 5.4 | 2.56–11.5 |

| LR− | 0.5 | 0.35–0.99 |

Analysis of sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV and likelihood ratios of the cases of bronchiolitis in reference to the ESBA scale.

| Bronchiolitis, severe condition | Bronchiolitis non-severe condition | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| ESBA scale, severe | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| ESBA scale, mild or moderate | 13 | 185 | 198 |

| 13 | 188 | 201 |

| 95% confidence interval | ||

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | 3.6% | 0.4–26.8 |

| Specificity | 98.1% | 95.1–99.3 |

| PPV | 12.5% | 1.3–60.4 |

| NPV | 93.2% | 88.8–96.0 |

| LR+ | 1.93 | 0.10–35.5 |

| LR- | 0.98 | 0.83–1.16 |

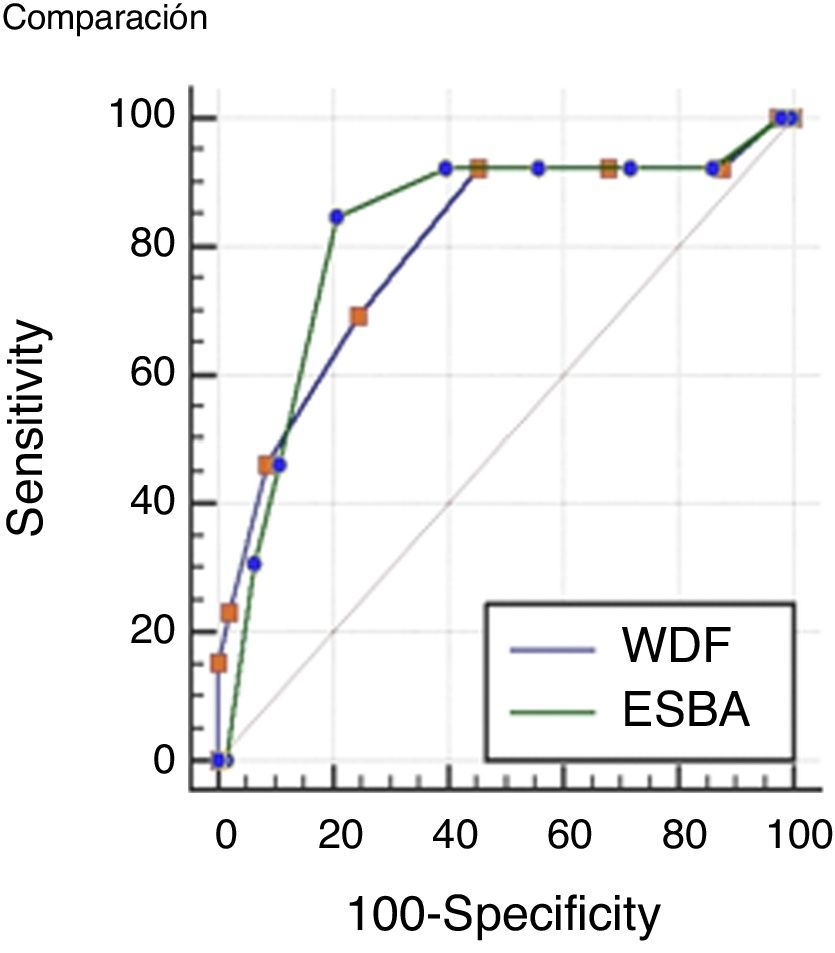

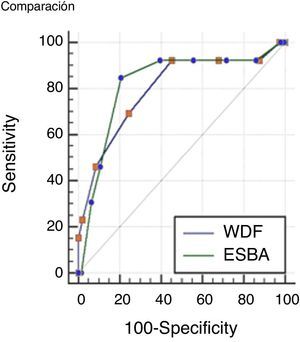

Comparisons were made of the ROC curves of each scale in order to determine which instrument is more accurate in assessing severe bronchiolitis. The results obtained are presented in Fig. 1.

The values of the AUC corresponding to the two scales were 0.79 (IC 95% 0.73–0.85) for the WDF score; and 0.82 (IC 95% 0.75–0.87) for ESBA. The difference between the two areas was 0.02 (95%CI: 0.01–0.15), which proved non-significant (p=0.72).

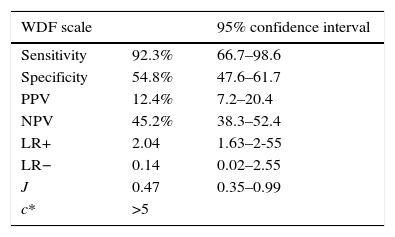

On considering our study sample, we could establish new cut-off points for the scales that were able to more precisely assess severe bronchiolitis. In this regard, we selected cut-off points with an optimum relationship between sensitivity and specificity, afforded by the Youden index (J). The data are shown in Table 5.

Analysis of sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV and likelihood ratios of the cases of bronchiolitis in reference to the WDF and ESBA scale, with the cut-off points derived from the study sample. Estimation of the Youden index (J) and optimum cut-off point (c*) of the scale for the sample (WDF >5 points and ESBA >6 points).

| WDF scale | 95% confidence interval | |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | 92.3% | 66.7–98.6 |

| Specificity | 54.8% | 47.6–61.7 |

| PPV | 12.4% | 7.2–20.4 |

| NPV | 45.2% | 38.3–52.4 |

| LR+ | 2.04 | 1.63–2-55 |

| LR− | 0.14 | 0.02–2.55 |

| J | 0.47 | 0.35–0.99 |

| c* | >5 |

| ESBA scale | 95% confidence interval | |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | 84.6% | 57.8–95.7 |

| Specificity | 78.7% | 72.3–84.0 |

| PPV | 21.6% | 12.5–34.6 |

| NPV | 98.7% | 95.3–99.6 |

| LR+ | 3.98 | 2.78–5.70 |

| LR− | 0.20 | 0.05–0.70 |

| J | 0.63 | 0.42–0.80 |

| c* | >6 |

Accordingly, in the sample of patients admitted to hospital due to AB in our study, the cut-off points offering the best relationship between Se and Sp were found to be lower than those proposed in the original studies. On lowering the threshold for defining bronchiolitis as severe (5 points in the case of WDF and 6 points in the case of ESBA), the scales were able to classify a larger number of patients as presenting severe bronchiolitis.

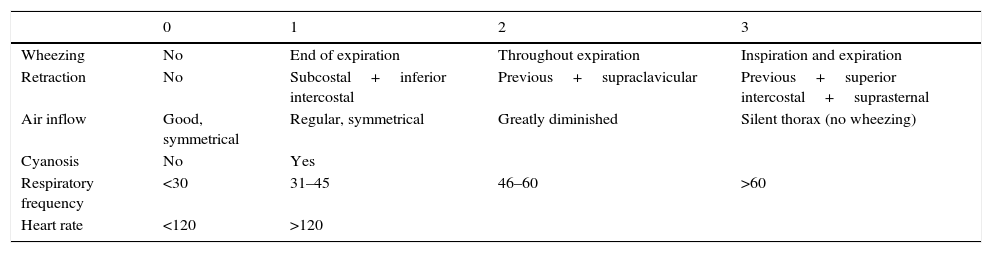

DiscussionThe WD scale in principle does not seem to be a good tool for the clinical evaluation of AB, since it was designed and published in 1972 for the assessment of respiratory failure in only 18 paediatric patients with asthma crisis.10 Valuable parameters such as respiratory frequency or heart rate stratified according to age, the presence of crackles or oxygen saturation were not contemplated in the mentioned publication. In the present study, the WDF scale yielded a high false negative rate with the original cut-off points, and therefore does not seem reliable for detecting severe bronchiolitis. On applying the cut-off points obtained from the sample, the WDF scale was seen to be able to detect more seriously ill patients, increasing the absolute number of true positive results.

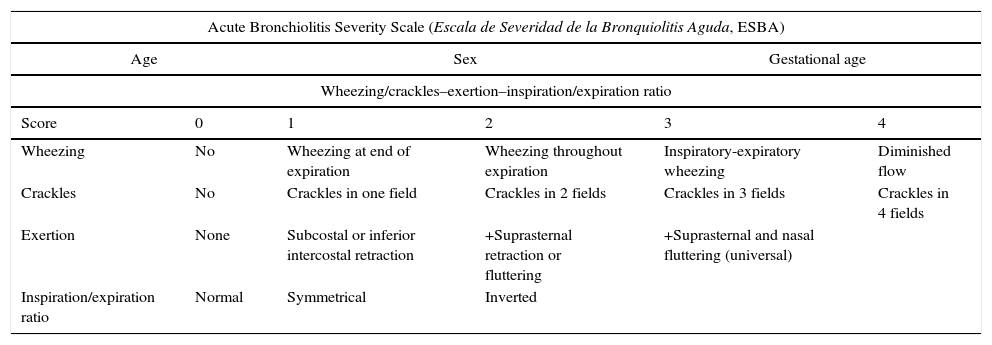

On the other hand, the ESBA12 offered the opportunity of working with an instrument exclusively designed for application to bronchiolitis, with good interobserver agreement (kappa index 0.682), employed in patients of our geographical setting, admitted to hospital and under one year of age. This scale contemplated the evaluation of signs such as crackles and wheezing (rated according to extent), and age stratification of respiratory frequency and heart rate – these being very objective measures. However, on analysing our large sample of infants with the cut-off points offered by the authors of the instrument, we found that the ESBA scale did not classify as severe any of those cases of bronchiolitis requiring non-invasive ventilation, transfer to the ICU or respiratory acidosis. With regard to the inclusion criteria, their patients did not differ very much from our own sample of infants, although the Se and Sp values published by the investigators did not coincide with our own values. The criteria used for admitting patients to the paediatric ICU or for deciding their destination may have been different from those of our own study. Nevertheless, the study of Ramos et al. lacks true validation of the scale with a sufficient sample of patients, classification based on the ESBA scale and the measurement of Se, Sp and an ROC curve with the different cut-off points. In this respect, on performing that analysis with our study sample, the ESBA scale yielded Se=84.6% and Sp=78.7, which differ considerably from the values reported by the authors of the original study. A very interesting finding was the recording of LR+=3.98, which indicates that an ESBA score of >6 obtained in a hospitalised patient with bronchiolitis implies an almost four-fold increase in the pre-test probability that the case of bronchiolitis is truly severe. Considering a pre-test probability of 12%, the post-test probability would be about 47.7% with an ESBA score of >6. On analysing the behaviour of the WDF scale, LR+ was even lower, with only a two-fold increase in the probability that the case of bronchiolitis is severe in the presence of a score of >5. Therefore, with the same prevalence of severe illness among the admitted patients, the post-test probability is about 24% if the WDF score is >5.

Both scales yielded low positive predictive values and also low LR+ and LR− values; as a result, neither instrument appears to be valid for discriminating those infants in our sample of patients that suffer truly severe bronchiolitis.

Although the positive and negative predictive values of the ESBA scale were higher than in the case of the WDF scale, the areas under the ROC curve were not significantly different; we therefore cannot conclude that one instrument is better than the other in differentiating severe cases of the disease.

In the context of the hospitalisation of these patients, it seems advisable to ensure the diagnosis of all seriously ill infants, since anticipating respiratory failure before it manifests is crucial. It is therefore worth ensuring higher Se values. For this reason, in our sample the cut-off points obtained with the ROC curves allow the negative results of the WDF and ESBA scales to more reliably discard severe cases.

In our study we only recorded 13 cases of severe bronchiolitis (6.4% of the total) – this being consistent with the data published in the literature, where the estimated paediatric ICU admission rate is 5–16%.8 However, our recorded transfer rate was 2.5%, which is lower than the percentages found in the literature. A number of factors may explain this observation, such as the exclusion of patients with background disorders capable of causing eventual bronchiolitis to be more severe, or the fact that three of the hospitals were equipped with non-invasive ventilation techniques such as CPAP or HFO therapy – which are useful for the management of severe bronchiolitis.15,16 Likewise, some cases of bronchiolitis could not be recruited and were lost, since the patients were transferred before they could be enrolled or before informed consent could be obtained from the parents.

The low number of patients with a severe condition generates a high imprecision estimation of the scales’ sensitivity and questions the results after modifying the cut-off points, even though they improve the estimated sensitivities.

The weaknesses of our study include the existence of multiple observers involved in patient assessment, and who did not receive specific instruction other than a training session about the study. In this regard, in relation to the degree of interobserver agreement, differences among studies are noted, although on measuring a series of clinical signs in patients with respiratory problems, the observed degree of agreement is low.17–19 It therefore seems advisable to use the largest possible number of objective variables that are less likely to differ between measurements.

One of the parameters of the ESBA scale – the inspiration/expiration ratio – appears to be particularly difficult to evaluate. The original study on this scale already identified this ratio as the weakest parameter in terms of interobserver agreement. In patients with high respiratory frequencies it can be difficult to establish whether inspiration and expiration are similar or whether one is prolonged with respect to the other. Furthermore, this ratio is not a vital parameter commonly considered in paediatric physical examination.8,9

Among the limitations of the study, results could change according to the gold standard used as a synonym for severity.

The low weighted kappa index found in the study shows the low concordance between measures found between scales.

Other investigations have attempted to validate and compare severity scales in application to bronchiolitis. A study carried out in the United States between 2007 and 2009 evaluated the suitability of two scales for assessing the severity of bronchiolitis using hospital admission and the duration of hospital stay as discrimination measures.20 These scales were the Respiratory Distress Assessment Instrument (RDAI) and The Children's Hospital of Wisconsin Respiratory Score (CHWRS), which yielded low areas under the ROC curves of 0.51 and 0.68, respectively. The study concluded that the RDAI is more limited than the CHWRS in defining the clinical condition of the patient at a concrete timepoint during hospital admission. In this regard it can be deduced that prior training is needed in order to establish reliable scoring, and that the scales can be useful for determining the efficacy of treatments or for assessing the time course referred to one same individual.

The RDAI scale has also been tested for predicting the risk of hospital admission and hospital stay in a multi-centre study involving patients with bronchiolitis, where oxygen saturation <94%, an RDAI score of >11 and a respiratory frequency of >60rpm were found to be the best predictors of hospital admission and prolonged stay in hospital.21

The scales used to score patient respiratory condition have been widely used to assess the efficacy of the different treatments used for bronchiolitis. However, few of these instruments have been specifically validated for this purpose. One of the best attempts to validate the modified Wood's Clinical Asthma Score (M-WCAS) for bronchiolitis was carried out by a group of investigators in a hospital between 2010 and 2011, with the assessment of usability, reproducibility and validity of the WDF scale in patients hospitalised because of bronchiolitis and under 24 months of age.22 This study effectively confirmed a correlation between high scores on the scale and admission to intensive care.

This same scale has been used to evaluate the efficacy of Heliox in patients admitted to the ICU, with satisfactory outcomes, since such treatment resulted in a reduction in the score of the instrument, a shortened ICU stay and a decrease in respiratory frequency and heart rate.23 However, none of these studies established comparisons with a scale exclusively designed for application to this disease.

On the other hand, bronchiolitis is a changing and dynamic disorder; point measurements therefore may be imprecise in assessing the final patient outcome, since they only reflect the moment of the disease in which the measurements were obtained. Measurements obtained in different moments could be useful to determine evolution changes in one patient, but not necessarily indicate the final course of the illness.

Most of the clinical data defined in the different clinical guidelines as parameters to be considered on deciding the admission of a patient with bronchiolitis are referred to young patient age, the background disease condition, the presence of apnoea and the degree of tachypnoea.9,24–27 In our study the bivariate analysis found these parameters to be consistent with the descriptions found in the literature, although our results also underscored the relevance of fever and patient rejection of food.

Recently, NICE guidelines for bronchiolitis have been published and recommend further research into the effectiveness of Paediatric Early Warning Score (PEWS) in predicting deterioration for infants with bronchiolitis. The Guideline Development Group encourages assessing scores that could predict bronchiolitis deterioration.28

In conclusion, clinical scales do not seem to be precise in assessing the severity of patients with bronchiolitis. Nevertheless, in our sample the ESBA scale with new cut-off points appears to be superior to the WDF scale in classifying patients as being in a severe condition, although the differences failed to reach statistical significance.

New validation studies are needed to confirm whether our new cut-off points better classify severe hospitalised infants with AB.

Ethical disclosuresConfidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data and that all the patients included in the study have received sufficient information and have given their informed consent in writing to participate in that study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects mentioned in the article.

Protection of human subjects and animals in researchAuthors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the responsible Clinical Research Ethics Committee and in accordance with those of the World Medical Association and the Helsinki Declaration.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Doctors who collected data in all the participating centres: Alicia Coret Sinisterra, Sergio Martín Zamora, Leonor García Maset, Aleixandre Castelló, Lidia Blasco González, José Haro Chuliá, Manuel Andrés Zamorano, Irene Satorre Viejo, Natividad Pons Fernandez, Ana Moriano Gutiérrez, Gemma Pedrón Marzal, Beatriz Beseler Soto, Julia Morata Alba, Pepe Cambra Sirera, Fernando Calvo Rigual, Begoña Pérez García, Marta San Roman, Maraña A, Torrecilla J, Hernández S, De La Osa A, Espadas D, Guardia L y Cueto E. We would also like to acknowledge Luis González Vasco for translation work and Sergio Fernández for the design and statistical analysis.

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wheezing | No | End of expiration | Throughout expiration | Inspiration and expiration |

| Retraction | No | Subcostal+inferior intercostal | Previous+supraclavicular | Previous+superior intercostal+suprasternal |

| Air inflow | Good, symmetrical | Regular, symmetrical | Greatly diminished | Silent thorax (no wheezing) |

| Cyanosis | No | Yes | ||

| Respiratory frequency | <30 | 31–45 | 46–60 | >60 |

| Heart rate | <120 | >120 |

Mild crisis: 1–3 points.

Moderate crisis: 4–7 points.

Severe crisis: 8–14 points.

| Acute Bronchiolitis Severity Scale (Escala de Severidad de la Bronquiolitis Aguda, ESBA) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Sex | Gestational age | |||

| Wheezing/crackles–exertion–inspiration/expiration ratio | |||||

| Score | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Wheezing | No | Wheezing at end of expiration | Wheezing throughout expiration | Inspiratory-expiratory wheezing | Diminished flow |

| Crackles | No | Crackles in one field | Crackles in 2 fields | Crackles in 3 fields | Crackles in 4 fields |

| Exertion | None | Subcostal or inferior intercostal retraction | +Suprasternal retraction or fluttering | +Suprasternal and nasal fluttering (universal) | |

| Inspiration/expiration ratio | Normal | Symmetrical | Inverted | ||

| Respiratory frequency | 0 points | 1 point | 2 points |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (months) | |||

| <2m | <57 | 57–66 | >66 |

| 2–6m | <53 | 53–62 | >62 |

| 6–12m | <47 | 47–55 | >55 |

| Heart rate | 0 points | 1 point | 2 points |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| 7 days–2 months | 125–152 | 153–180 | >180 |

| 2–12 months | 120–140 | 140–160 | >160 |