Allergic rhinitis (AR) is the most common allergic disease in childhood. Nasal obstruction is a typical symptom of AR, however, its quantification by clinical examination is difficult. To provide an objective assessment of nasal patency, the peak nasal inspiratory flow (PNIF) is used. Symptoms of AR have a noticeable impact on the quality of life. The aim of this study was to assess which factors may have an impact on PNIF values and to evaluate the possible relationships between PNIF and QoL in children with AR.

Patients and MethodsWe recruited patients aged 6–17 years (n = 208, 89 girls and 119 boys) with AR. All children underwent PNIF measurements. Parents and children completed KINDL-R generic questionnaires, to assess the quality of life of the children.

ResultsThe average PNIF value was 98.9 ± 37.4 L/min. A very strong (p < 0.001) relationship between the PNIF value and height, age and weight of the child was observed. The sex of the patient has no influence on the PNIF value. We showed that PNIF values significantly increased with each attempt. The children assessed their QoL at 45.6 ± 8.5 points in the KINDL-R questionnaire and the parents rated their children’s QoL at 73.7 ± 10.7 points. We observed a weak negative correlation between PNIF and the QoL based on the parents’ assessment and the child’s self-assessment.

ConclusionsPNIF values depend mostly on height, but also on the child’s age and weight. A learning effect (significant increase in PNIF upon each attempt) was shown. Higher PNIF does not improve the QoL.

Allergic rhinitis (AR) is the most common allergic disease in childhood. The typical and common symptoms of AR are rhinorrhoea, nasal obstruction, nasal itching and paroxysmal sneezing. Others include conjunctivitis, impaired smell as well as general signs such as lack of concentration. Due to their recurrence or chronicity, these seemingly insignificant symptoms, often occurring in the course of the common infection, become troublesome for patients with AR.

Nasal obstruction is a typical symptom of AR, however, its quantification by clinical examination is difficult. To provide an objective assessment of nasal patency different methods are used. The most common techniques are: rhinomanometry, acoustic rhinometry and peak nasal inspiratory flow (PNIF). Rhinomanometry measures pressure and flow during normal inspiration and expiration through the nose. Acoustic rhinometry measures the cross-sectional areas in predetermined points in the nasal cavity. PNIF can be measured using a Youlten peak nasal inspiratory flow meter (an inverted mini-Wright flow meter) attached to a facial mask. It is an inexpensive, non-invasive, portable, and relatively simple measure and can thus be successfully used in children.1 Ambiguous scientific reports on the correlation of PNIF with age, height, weight and gender in the published studies probably result from differences in the analysed populations, but they indicate PNIF as a frequently and successfully used nasal patency assessment method and so justify the need for further research. In the available literature, studies regarding the objective measurement of nasal patency in children, such as PNIF, are still scarce.

Symptoms of AR have a noticeable impact on the quality of life (QoL) and make it difficult to perform everyday activities — children with AR may have difficulties at school related to fatigue, irritability, and sleep disorders.2,3 Participating in social and family meetings may be a problem for them, which results in emotional disorders and leads to sadness, anger, frustration and withdrawal.4 It seems interesting whether and how objectively-measured symptoms of AR such as nasal obstruction can affect the quality of the child’s life.

The aim of this study was to assess which factors may have an impact on PNIF values and to evaluate the possible relationships between PNIF and QoL in children with AR.

Patients and methodsWe recruited patients aged 6–17 years (n = 208, 89 girls and 119 boys) with AR from the Lower Silesian region, Poland. All children underwent clinical assessments and a general medical history, information about age, height, weight, gender and place of residence was obtained from the parent of each patient. The AR diagnosis was confirmed by clinical history and skin prick tests with a panel of ten aeroallergens, including grass pollen, birch pollen, mugwort, hazel, alder, common rye, cat fur, Dermatophagoides farinae, Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus, Alternaria (HAL Allergy, The Netherlands). In addition, histamine and saline were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. The wheal size was recorded after 15 min and an average wheal diameter of 3 mm was considered positive. Sixty-five percent of all children had allergy to seasonal allergens or both seasonal and perennial allergens and were examined during the pollen season, so they were included in the seasonal group. The rest, allergic to perennial allergens, were tested outside the pollen season and formed a separate group. In the study group, 19 patients (9%) showed allergy to a single allergen and 189 (91%) were polysensitized. The average duration of AR since diagnosis was 2.5 years and the average patient age at the time of AR diagnosis was 9.5 years. The whole study group was divided into two age subgroups (group 1 — children aged 6–13, and group 2 — children aged 14–17) according to the division in the QoL questionnaire used in the research. The most important clinical and demographic characteristics of the population that was studied are shown in Table 1.

Patients characteristics.

| Characteristic | Whole group (6–17 years) N = 208 | Group I (6–13 years) N = 133 | Group II (14–17 years) N = 75 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| Sex: | |||||||

| Girls | 89 | 42.8 | 56 | 42.1 | 33 | 44.0 | |

| Boys | 119 | 57.2 | 77 | 57.9 | 42 | 56.0 | |

| Place of living: | |||||||

| Town >15.000 residents | 76 | 36.5 | 45 | 33.8 | 31 | 41.3 | |

| Town <15.000 residents | 36 | 17.3 | 17 | 12.8 | 19 | 25.3 | |

| Village | 96 | 46.2 | 71 | 53.4 | 25 | 33.3 | |

| Age (years): | |||||||

| M ± SD | 11.7 ± 3.0 | 9.8 ± 2.0 | 15.0 ± 1.3 | ||||

| Me [Q 1; Q 3] | 12 [9; 14] | 10 [8; 12] | 15 [14; 16] | ||||

| Min–Max | 6–17 | 6–13 | 14–17 | ||||

| Allergy to seasonal or seasonal and perennial allergens | 136 | 65.4 | 85 | 63.9 | 51 | 68.0 | |

| Allergy to perennial allergens | 72 | 34.6 | 48 | 36.1 | 24 | 32.0 | |

M: mean; SD: standard deviation; Me. Median; Q1: lower quartile; Q3: upper quartile; Min: minimum; Max: maximum.

PNIF was used to provide an objective evaluation of nasal patency. The Clement Clarke In-Check Nasal portable inspiratory flow meter was used. It is a modified Wright-flow meter, which is composed of a meter and a face mask covering the nose without touching it. To measure PNIF, the child had to be in a standing position, then he/she had to exhale deeply and, after applying the mask, inhale quickly and deeply through the nose. This activity was repeated three times and the highest value obtained was recorded. The result was shown in litres per minute (L/min).

Parents and children completed KINDL-R generic questionnaires, which are used to assess the QoL of the children, independently of each other.5 The questionnaires for children aged 7–17 years (Kid-KINDL: 7–13 years of age and Kiddo-KINDL: 14–17 years of age) include 24 questions related to feelings during the previous week in six dimensions: physical well-being, emotional well-being, self-esteem, family, friends, and functioning in everyday life (school or nursery school/kindergarten) with five possible answers (never, rarely, sometimes, often, all the time). The version for younger children, Kiddy-KINDL (4–6 years of age) also refers to six dimensions but consists of only 12 questions with three possible answers. The parental proxy-versions are appropriately modelled using the respective children’s versions. The sum of points ranges from 0 (worst) to 100 (best), where higher scores indicate a better QoL.

The Ethics Committee at the Wroclaw Medical University approved this study, and the parents of all the participants and children over 16 provided their informed consent in writing. They were given detailed information about the study and the possibility to withdraw from the participation at any time.

Qualitative variables are presented in tables and figures in the form of numbers (n) and percentages (%). For quantitative variables, mean values (M), standard deviations (SD), medians (Me), upper and lower quartiles (Q1, Q3) and extreme values (Min, Max) were calculated. The compliance of the empirical distributions of quantitative variables with the normal distribution was verified using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. To assess the significance of differences between average PNIF values in successive samples, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and post-hoc test, Tukey’s test was used. The strength and direction of the relationship between PNIF and QoL was assessed by calculating the Pearson correlation coefficient r and its 95% confidence interval. For all tests, p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. The analyses were performed with STATISTICA v.12.5 (StatSoft, Inc., USA).

ResultsThe average PNIF value was 98.9 ± 37.4 L/min (minimum 40 L/min, maximum 240 L/min) in the whole group. Younger children’s PNIF value was 84.44 ± 27.5 L/min (minimum 40 L/min, maximum 180 L/min) and older children’s PNIF value was 124.6 ± 129 38.9 L/min (minimum 60 L/min, maximum 240 L/min). A very strong (p < 0.001) relationship between the PNIF value and the age of the child was observed.

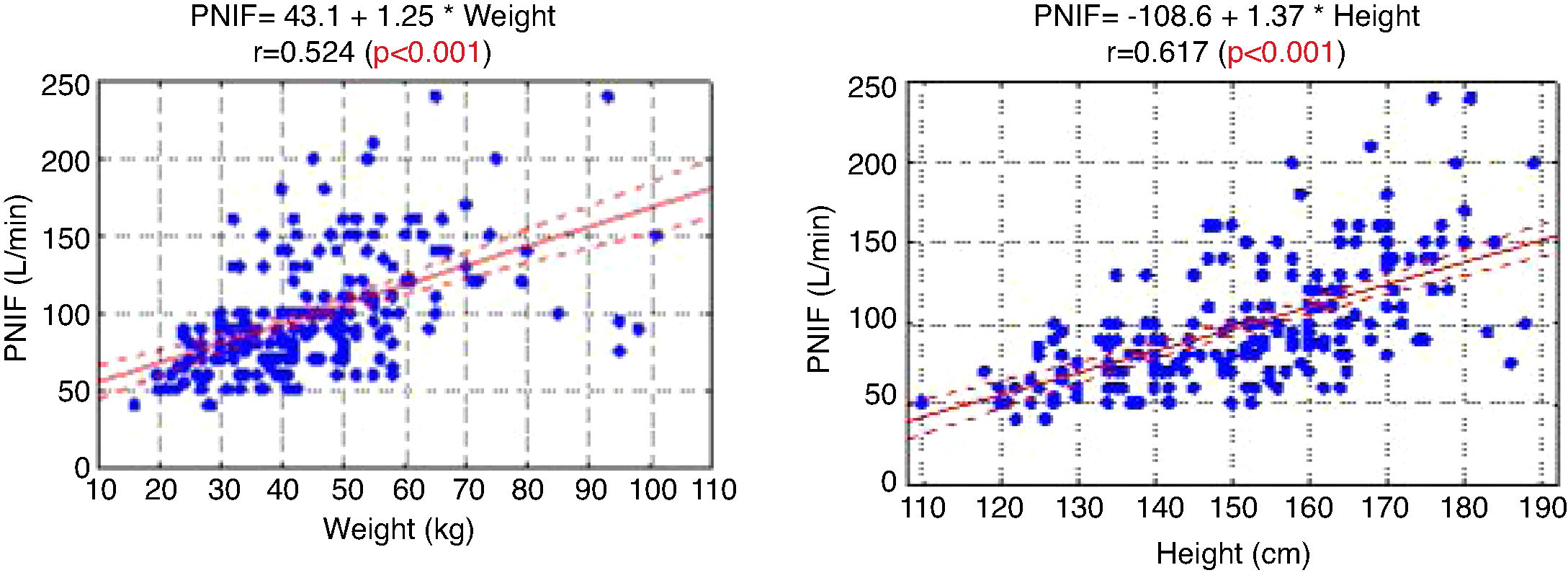

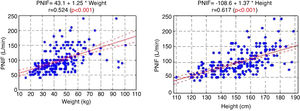

The PNIF values also strongly correlated with the weight and height of the patient (Fig. 1).

There was no relationship between PNIF and the gender of the child (p = 0.223). Similarly, there were no significant differences in the PNIF values in children with different AR types or place of residence. The number of allergens to which the child was allergic did not affect the PNIF value obtained either. The type of child’s sensitization (monovalent/polyvalent) had also no statistically significant influence on the QoL assessment, performed both by the child and the parent.

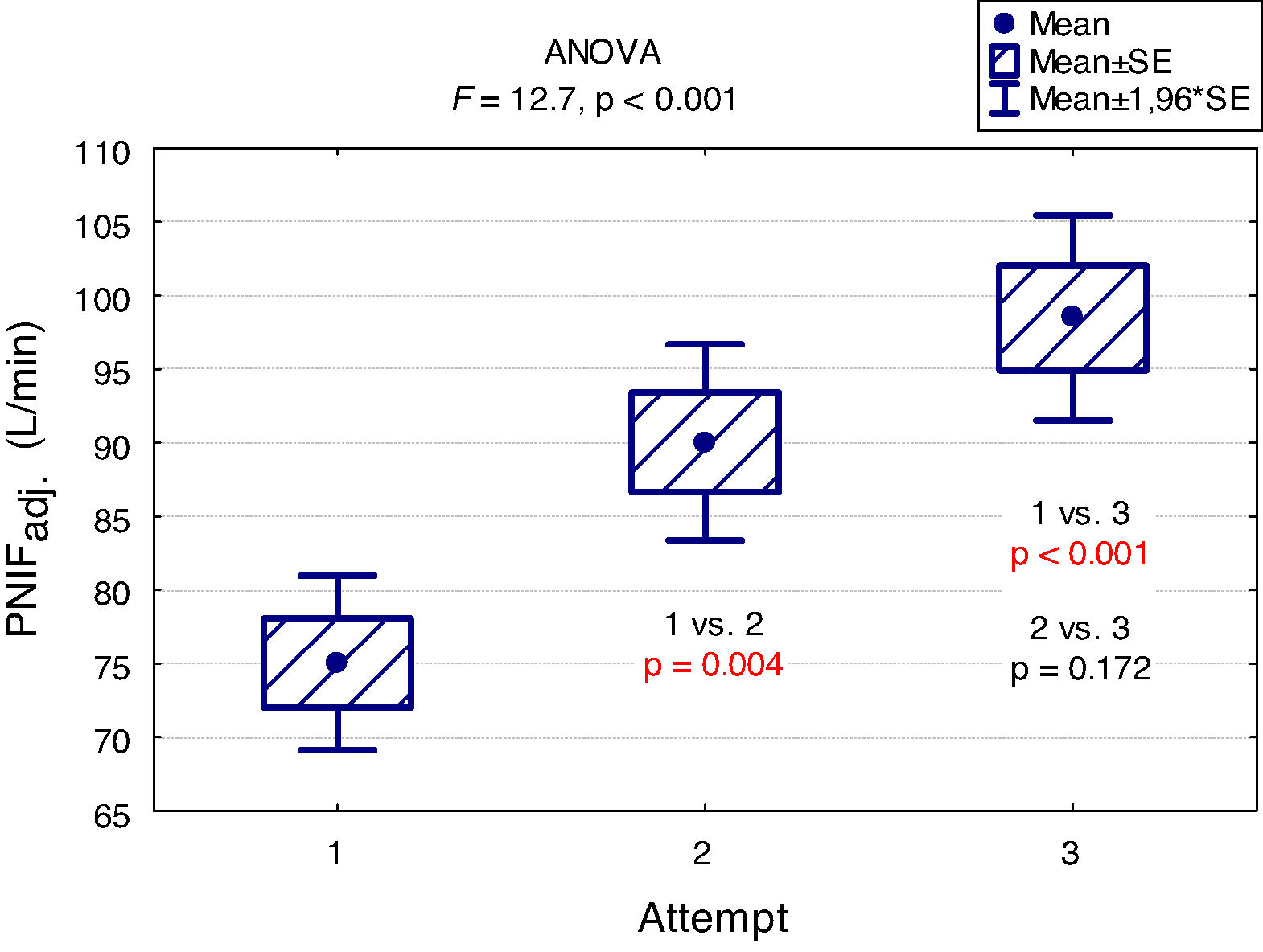

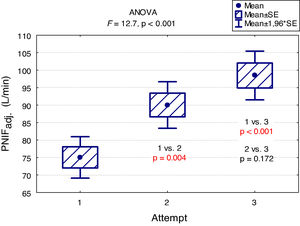

A "learning effect" was observed, which means that the results were higher in each subsequent measurement. Differences between the first and the second measurement as well as between the first and the third one were statistically significant (Fig. 2).

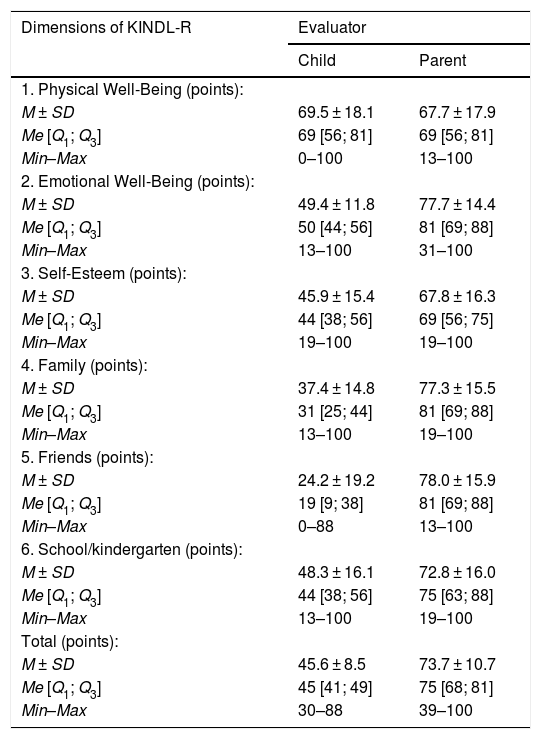

The children assessed their QoL at 45.6 ± 8.5 points in the KINDL-R questionnaire. The parents rated their children’s QoL higher, i.e. at 73.7 ± 10.7 points. Slightly higher result of QoL assessment was obtained by children from the younger age group (46.5 ± 9.6) in comparison with the group of older children (44.0 ± 5.9). The QoL ratings in each assessed domain are presented in Table 2.

Results of the assessment of child’s quality of life on the KINDL-R questionnaire.

| Dimensions of KINDL-R | Evaluator | |

|---|---|---|

| Child | Parent | |

| 1. Physical Well-Being (points): | ||

| M ± SD | 69.5 ± 18.1 | 67.7 ± 17.9 |

| Me [Q1; Q3] | 69 [56; 81] | 69 [56; 81] |

| Min–Max | 0–100 | 13–100 |

| 2. Emotional Well-Being (points): | ||

| M ± SD | 49.4 ± 11.8 | 77.7 ± 14.4 |

| Me [Q1; Q3] | 50 [44; 56] | 81 [69; 88] |

| Min–Max | 13–100 | 31–100 |

| 3. Self-Esteem (points): | ||

| M ± SD | 45.9 ± 15.4 | 67.8 ± 16.3 |

| Me [Q1; Q3] | 44 [38; 56] | 69 [56; 75] |

| Min–Max | 19–100 | 19–100 |

| 4. Family (points): | ||

| M ± SD | 37.4 ± 14.8 | 77.3 ± 15.5 |

| Me [Q1; Q3] | 31 [25; 44] | 81 [69; 88] |

| Min–Max | 13–100 | 19–100 |

| 5. Friends (points): | ||

| M ± SD | 24.2 ± 19.2 | 78.0 ± 15.9 |

| Me [Q1; Q3] | 19 [9; 38] | 81 [69; 88] |

| Min–Max | 0–88 | 13–100 |

| 6. School/kindergarten (points): | ||

| M ± SD | 48.3 ± 16.1 | 72.8 ± 16.0 |

| Me [Q1; Q3] | 44 [38; 56] | 75 [63; 88] |

| Min–Max | 13–100 | 19–100 |

| Total (points): | ||

| M ± SD | 45.6 ± 8.5 | 73.7 ± 10.7 |

| Me [Q1; Q3] | 45 [41; 49] | 75 [68; 81] |

| Min–Max | 30–88 | 39–100 |

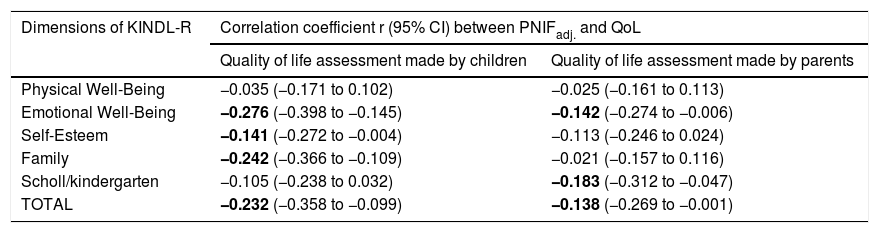

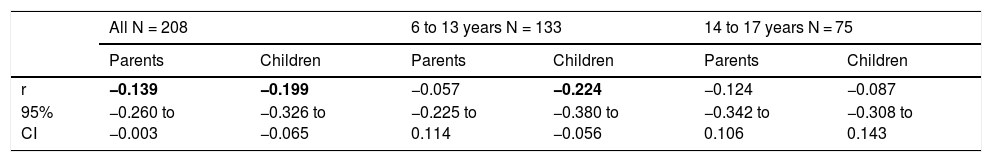

PNIF values were adjusted for the child’s body height. There was no need to adjust PNIF for other variables (sex, age, BMI, etc.) because these variables correlate strongly with body height and taking body height into account was sufficient. We observed a negative statistically significant correlation between PNIF and the QoL of the child on the basis of the child’s self-assessment and the parents’ assessment (Table 3). This relationship was also checked in the age subgroups. A negative correlation between PNIF and the QoL was observed only in the group of younger children (Table 4).

Values of linear correlation coefficients (r) of PNIFadj. with the assessment of the quality of life made by children and parents (PNIFadj.- PNIF adjusted to body height).

| Dimensions of KINDL-R | Correlation coefficient r (95% CI) between PNIFadj. and QoL | |

|---|---|---|

| Quality of life assessment made by children | Quality of life assessment made by parents | |

| Physical Well-Being | −0.035 (−0.171 to 0.102) | −0.025 (−0.161 to 0.113) |

| Emotional Well-Being | −0.276 (−0.398 to −0.145) | −0.142 (−0.274 to −0.006) |

| Self-Esteem | −0.141 (−0.272 to −0.004) | −0.113 (−0.246 to 0.024) |

| Family | −0.242 (−0.366 to −0.109) | −0.021 (−0.157 to 0.116) |

| Scholl/kindergarten | −0.105 (−0.238 to 0.032) | −0.183 (−0.312 to −0.047) |

| TOTAL | −0.232 (−0.358 to −0.099) | −0.138 (−0.269 to −0.001) |

Values of Pearson correlation coefficients (r) between the PNIF and children quality of life assessed by parents and children.

| All N = 208 | 6 to 13 years N = 133 | 14 to 17 years N = 75 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parents | Children | Parents | Children | Parents | Children | |

| r | −0.139 | −0.199 | −0.057 | −0.224 | −0.124 | −0.087 |

| 95% CI | −0.260 to −0.003 | −0.326 to −0.065 | −0.225 to 0.114 | −0.380 to −0.056 | −0.342 to 0.106 | −0.308 to 0.143 |

The main findings of our study are as follows: PNIF depends mostly on height, but also on age and weight of the child (usually correlated with height) while it has no relation with the gender of the child or the type of AR he/she suffers from. The place of residence of the child and the number of allergens to which the child is allergic do not affect the PNIF value either. We showed that PNIF values significantly increased with each attempt with the highest average values recorded during the third attempt. We also observed a weak negative correlation between PNIF and the QoL based on the parents’ assessment and the child’s self-assessment.

In the study aimed at establishing PNIF reference values in the Polish people living in cities, it was found that the average PNIF results were 75.95 L/min in children aged 6–7, 91.44 L/min in children aged 13–14, and 97.13 L/min in adults. The results strongly correlated with age. As shown in our study, the height and weight of the children had a significant impact on the PNIF value. Gender did not affect the value of PNIF, nor was it significant whether the individuals had seasonal or perennial AR.6

In the study conducted as part of the Epidemiology of Allergic Diseases in Poland (ECAP) project, PNIF was measured in 4674 patients living in rural and urban areas, 27.6% of whom were children aged 6–7, 27.7% were teenagers aged 13–14 and 44.7% were adults. Perennial AR was diagnosed in 14.5% of all the population, and seasonal AR in 13.1%. The relationship between PNIF and age, sex, place of residence and health status was examined. Similarly to our results, the PNIF values increased along with the age of the patient. The authors measured PNIF before and after the intranasal administration of 0.05% oxymetazoline hydrochloride to improve the patency of the nasal passages. The average PNIF values in patients aged 6–7 was 52.53 L/min before the administration of the drug and 64.80 L/min after its administration, in children aged 13–14: 92.26 L/min before the administration of the drug and 116.73 L/min after the administration of the drug, in adults: 104.47 L/min before the administration of the drug and 128.94 L/min after the administration of the drug. The researchers reported higher PNIF values in men than in women, in healthy patients than in ill ones, and in those living in urban rather than rural areas. Sick adults and adolescents with persistent AR had statistically higher PNIF than those with seasonal AR. In the group of children aged 6–7, the results were also higher in patients with persistent AR, but the difference was not statistically significant.7 Choosing only healthy participants living in Wroclaw from the above study group, Dor-Wojnarowska et al. showed that PNIF depended on the sex and height of 221 subjects, while there was no correlation between PNIF and age.8 In an attempt to establish PNIF reference values in Turkey, 5554 healthy children aged 10.8 ± 2.9 years attending primary schools, were examined. The average PNIF was 71.34 ± 32.63 L/min and depended on the patient’s age, weight and height as shown in our study and, contrary to our results, on the sex of the child - the boys had a higher PNIF than the girls.9 A study conducted in Greece on 4111 healthy children aged 5–18 showed that PNIF increased with the age of the child and that significant differences in PNIF values between sexes were observed in patients over 12. However, in patients under 12, boys had a slightly higher PNIF than girls but which was not statistically significant.10 On the other hand, Van Spronsen et al., examining 212 Dutch children aged 6–11, stated that only age influenced the PNIF values. Sex, height, weight or race did not have a significant impact on PNIF. The authors also showed, just as we did in our study, the occurrence of the "learning effect" — in each subsequent measurement the PNIF values were higher. Therefore, it is advisable to use three measurements and choose the highest result obtained by the patient.11 Starling-Schwanz et al. examined 283 young adults, half of whom had AR, and found that PNIF correlates with AR symptoms if they are measured by a doctor using anterior rhinoscopy and that it does not correlate with them at all if they are evaluated on the basis of the questionnaire. This would mean that the subjective feelings of the patient may be completely different from the values achieved in objective research.12 This confirms the advantage of using several different methods of assessing patients rather than relying on single, objective or subjective, measurements.

In the results of the QoL assessment, we presented that the children considered their social contacts with their families and friends as the worst. The domain rated highest by the children was physical well-being. However, as far as the parents’ opinion on their children’s QoL is concerned, the domains of physical health and self-esteem were granted the lowest grades whereas that of social contacts was rated highest. The fact that the parents assessed QoL higher than the children has also been explored in previous studies.13,14

In our study, we observed a weak negative correlation between PNIF and the QoL in the group of younger children. This unexpected outcome may result from the wide range of age of the children with AR invited to participate in the study. Maybe younger children do not consider impaired nasal patency as a problem or if this symptom lasts longer, they simply get used to it. Perhaps the QoL assessment is much more independent from objectively measured disease symptoms than we thought. These surprising findings prove that additional studies need to be conducted to understand more about children’s QoL. An important question would be how adults assess their QoL in comparison with PNIF it is also worth checking whether this relationship occurs in healthy children as well.

In recent studies, authors showed that subjective feeling of nasal congestion was not always reflected in the results obtained using objective evaluation methods such as PNIF or rhinomanometry.15–18 Therefore, the QoL assessment (depending on the symptoms perceived) may not be related to the objective result of PNIF. It only confirms that both the QoL questionnaire and PNIF measurements are useful tools that can be used together to ensure better follow-up of patients with AR.

In the report presented at the XXII World Allergy Congress describing the results of the study which involved 100 paediatric patients with AR residing in India, one could read that the QoL results were worse with the decline in PNIF.19 In Poland, no studies have been conducted so far to compare the assessment of QoL and nasal patency expressed as PNIF.

Some limitations of our study are presented below. KINDL-R, which is a generic questionnaire, was used to assess the overall health-related QoL. It may seem that it will result in a lower sensitivity of the QoL assessment. However, the KINDL-R questionnaire was successfully used in other studies, involving both healthy and ill children as well. Authors of the GABRIEL study (A Multidisciplinary Study to Identify the Genetic and Environmental Causes of Asthma in the European Community) also used the KINDL-R questionnaire. By including this questionnaire in the parent survey, they were able to assess the QoL of children with asthma and AR living in urban and rural environments in several European countries, including Poland.20 The KINDL-R questionnaire was also chosen by us due to its availability in Polish language for young children. The most popular specific questionnaire for children with AR — PRQLQ has not been translated into Polish. Due to complicated procedures connected with adaptation, we did not receive permission from the authors for translation. Perhaps the use of a specific questionnaire focused on AR symptoms would allow a different perspective on the relationship between nasal obstruction and QoL. Further research is required to check this interesting issue.

On the other hand, according to our knowledge, for the first time in Poland, in the presented study, the PNIF value was evaluated by comparing it with QoL measurements provided by children and their parents. The PNIF measurement was carried out on a large group of children in comparison to the data available in the literature. This study was accessible for children who were eager to take part in it.

ConclusionsIn conclusion, our findings indicate that PNIF is a simple way to assess nasal patency. The result of the measurement depends mostly on height, but also on age and weight of the child (usually correlated with height). The sex of the patient has no influence on the PNIF value. We showed a learning effect — significant increase in PNIF upon each attempt. This finding suggests that making at least three attempts and then choosing the highest PNIF is required in children to obtain the proper values. Higher PNIF does not improve the QoL. As far as children with AR are concerned, PNIF is an important research tool that provides additional objective information about the patient.

Ethics approval and consent to participateInformed consent was obtained by all parents of individual participants included in the study and also by all participants aged more than 15 years, and the study received approval from the Wroclaw Medical University Ethics Board (number: KB-16/2017).

FundingThis research was supported by scholarship from the Wroclaw Medical University Young Researchers Fund (Grant Number: STM.A220.17.048). Authors did not receive any salary or financial support.

Declarations of interestNone.

Not applicable.