Beekeepers and their families are at an increased risk of life-threatening anaphylaxis due to recurrent bee-sting exposures.

ObjectiveThe aim of this study is to evaluate the demographic features, previous history of anaphylaxis among beekeepers and their family members, and their knowledge about the symptoms and management of anaphylaxis.

MethodsA standardized questionnaire was administered to beekeepers during the 6th International Beekeeping and Pine Honey Congress held in 2018, in Mugla, Turkey. Additionally, food-service staff from restaurants were surveyed as an occupational control group about their knowledge about anaphylaxis.

ResultsSixty-nine beekeepers (82.6% male, mean age 48.4±12.0 years) and 52 restaurant staff (46.2% male, mean age 40.5±10.0 years) completed the questionnaire. Awareness of the terms ‘anaphylaxis’ and ‘epinephrine auto-injector’ among the beekeepers were 55.1% and 30.4% and among the restaurant staff were 23.1% and 3.8%, respectively. Of the beekeepers, 74% were able to identify the potential symptoms of anaphylaxis among the given choices; 2.9% and 5.8% reported anaphylaxis related to bee-stings in themselves and in their family members, respectively. None of the restaurant staff had experienced or encountered anaphylaxis before but 3.8% of their family members had anaphylaxis and those reactions were induced by drugs.

ConclusionIt is essential that implementation of focused training programs about anaphylaxis symptoms and signs as well as practical instructions of when and how to use an epinephrine auto-injector will decrease preventable morbidities and mortalities due to bee-stings in this selected high-risk population of beekeepers and their family members, as well as other fieldworkers under risk.

Reactions to bee stings can vary widely from mild local reactions to life-threatening severe systemic reactions such as anaphylaxis.1–4 Epidemiological studies conducted in Europe have reported that 0.3%–7.5% of adults and 3.4% of children have experienced a systemic reaction to a bee sting.5–9 The incidence of bee sting-related death is around 0.03–0.48/1,000,000 accounting for about 20% of all fatalities due to anaphylaxis.10,11

Anaphylaxis is a life-threatening emergency condition. Immediate first intervention and treatment at the onset of reaction are critical and lifesaving. It is recommended that all patients with a history and/or risk of anaphylaxis should be prescribed and trained as to how and when to administer an epinephrine auto-injector during an anaphylaxis event.4,12 In the general population some occupational groups such as farmers, medical staff and food industry workers are at increased risk of encountering and/or experiencing anaphylaxis. Among them, beekeepers and their family members are at high risk for anaphylaxis due to bee stings.13,14 A study conducted in Turkey reported that 2% of beekeepers had anaphylaxis due to bee stings.13 The present study aimed to evaluate the knowledge level of symptoms and treatment of anaphylaxis among a selected group of Turkish beekeepers, as well as their personal and family history of anaphylaxis. Their awareness and attitudes about anaphylaxis were compared to restaurant staff, who were at increased potential to encounter anaphylaxis irrelevant to bee stings.

Materials and methodsParticipantsThe study was conducted during the 6th International Mugla Beekeeping and Pine Honey Congress held in Mugla, Turkey between 15 and 19 October, 2018. A total of 460 participants who are beekeepers and bee products manufacturers attended the congress. Sixty-nine beekeepers practicing beekeeping in different regions of Turkey were included in the study. All study subjects agreed to fill out the questionnaire. As an occupational control group, 52 restaurant staff, who were working in processes of cooking and serving foods agreed to fill out the questionnaire among seven of nine invited restaurants in Istanbul. Ethical approval was obtained from the Istanbul University, Istanbul Faculty of Medicine, Clinical Research Ethics Committee (2019/439) and participants were informed about the study.

The questionnaireA questionnaire inquiring data about the beekeepers’ and restaurant staff's demographic characteristics, their knowledge level about anaphylaxis symptoms and treatment, previous personal and family history of atopic diseases and anaphylaxis, the number of previous bee stings, species of stinging bees, history of adverse reactions to those bee stings, and their treatment attitudes following a bee sting was completed by the study subjects under supervision of researchers. The questionnaire can be accessed from supplementary files.

Statistical analysisThe SPSS software package version v.24.0 (IBM Corp. Released 2016. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 24.0. Armonk, NY, USA: IBM Corp.) was used for the statistical analysis of data obtained in the study. Descriptive statistics of categorical and numerical variables were expressed as frequencies and means with standard deviation for normally distributed variables or as medians with minimum-maximum values in parentheses for non-normally distributed variables. Comparisons of independent groups were done with Student's t test for values with normal distribution, Mann–Whitney U test for values with non-normal distribution, and chi-square (χ2) test for categorical variables. A value of p<0.05 was considered significant.

ResultsThe findings were analyzed under three subheadings: I. demographic data, II. level of knowledge about anaphylaxis signs, symptoms and treatment, and III. personal and family history of bee stings and allergic diseases. Study and control group subjects were classified into two groups based on their awareness of the terms of ‘anaphylaxis’ and/or ‘allergic shock’.

Demographic dataThe mean age of the beekeepers was 48.4±12.0 years (median=50 years), and 82.6% (n=57) of them were male. The median duration of beekeeping was 20 (minimum–maximum=0–50) years and 17.4% (n=12) of them were continuing beekeeping as a family profession from the older generation.

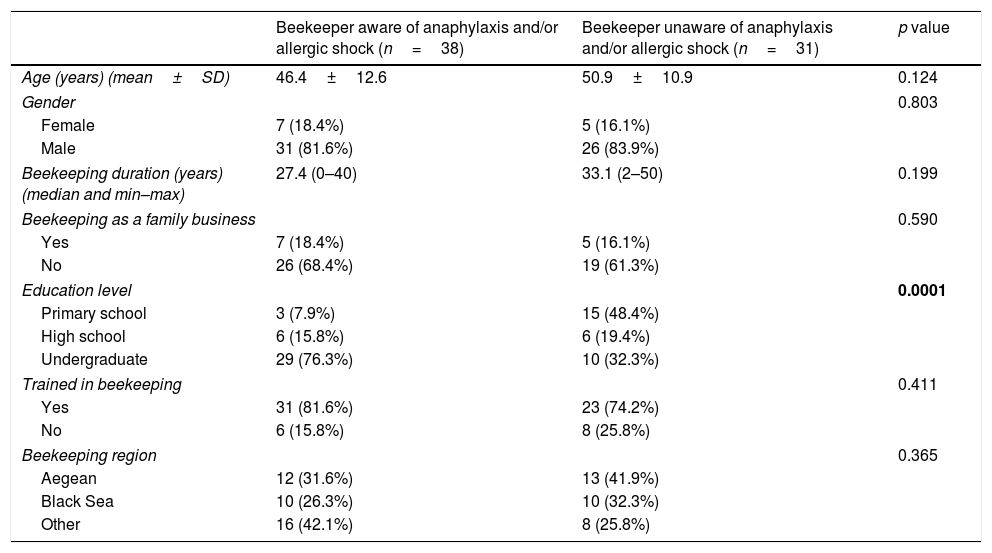

Data about education levels, training status for beekeeping of the participants and the region of the beekeeping were also inquired. Awareness with the terms of ‘anaphylaxis’ and/or ‘allergic shock’ was not associated with any significant difference in terms of age, gender, beekeeping duration, beekeeping as family profession, training status for beekeeping, and the region of the beekeeping. However, respondents with an undergraduate degree were significantly more familiar with the terms of ‘anaphylaxis’ and/or ‘allergic shock’ than high school or primary school graduates (p=0.0001). (Table 1).

Demographic data.

| Beekeeper aware of anaphylaxis and/or allergic shock (n=38) | Beekeeper unaware of anaphylaxis and/or allergic shock (n=31) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) (mean±SD) | 46.4±12.6 | 50.9±10.9 | 0.124 |

| Gender | 0.803 | ||

| Female | 7 (18.4%) | 5 (16.1%) | |

| Male | 31 (81.6%) | 26 (83.9%) | |

| Beekeeping duration (years) (median and min–max) | 27.4 (0–40) | 33.1 (2–50) | 0.199 |

| Beekeeping as a family business | 0.590 | ||

| Yes | 7 (18.4%) | 5 (16.1%) | |

| No | 26 (68.4%) | 19 (61.3%) | |

| Education level | 0.0001 | ||

| Primary school | 3 (7.9%) | 15 (48.4%) | |

| High school | 6 (15.8%) | 6 (19.4%) | |

| Undergraduate | 29 (76.3%) | 10 (32.3%) | |

| Trained in beekeeping | 0.411 | ||

| Yes | 31 (81.6%) | 23 (74.2%) | |

| No | 6 (15.8%) | 8 (25.8%) | |

| Beekeeping region | 0.365 | ||

| Aegean | 12 (31.6%) | 13 (41.9%) | |

| Black Sea | 10 (26.3%) | 10 (32.3%) | |

| Other | 16 (42.1%) | 8 (25.8%) | |

SD: Standard deviation.

bold p value: statistically significant.

The mean age of the restaurant staff was 40.5±10.0 years (median=41.5 years), and 46.2% (n=24) of them were male. The median duration of working experience in the food industry was 7.5 (minimum-maximum=1–66) years. Awareness with the terms of ‘anaphylaxis’ and/or ‘allergic shock’ was not associated with any significant difference in terms of age, gender, the duration of experience in the food industry, whether they had received training for cooking or not and education level (supplementary files).

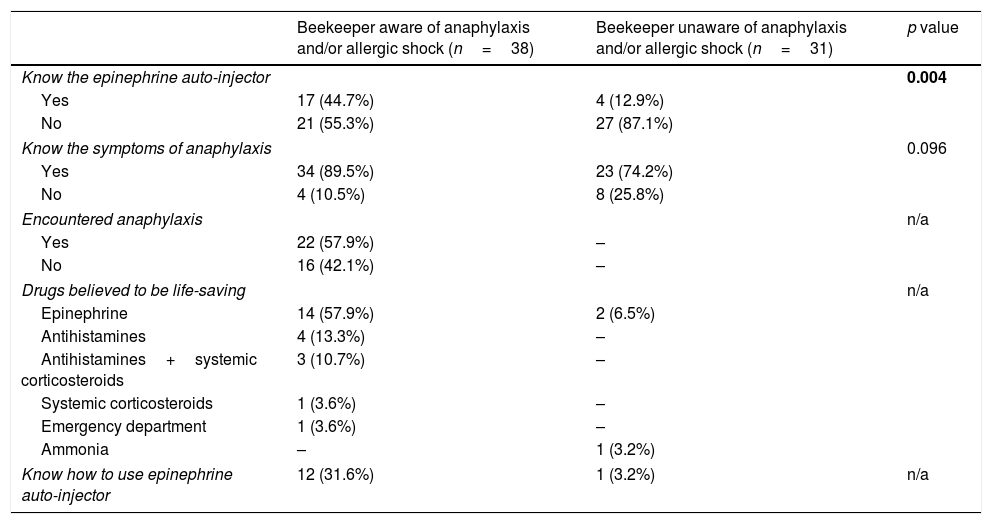

Level of knowledge about anaphylaxis symptoms and treatmentOf the beekeepers, 55.1% (n=38) had knowledge about the terms of ‘anaphylaxis’ and/or ‘allergic shock’. A significantly higher proportion of the group that was aware with anaphylaxis were also familiar with an epinephrine auto-injector (p=0.004). Of the beekeepers who claimed to be unaware about anaphylaxis, 74.2% were able to identify the potential symptoms of anaphylaxis from the questionnaire. Knowledge levels of the beekeepers regarding the symptoms and treatment of anaphylaxis are summarized in Table 2.

Beekeepers’ levels of knowledge about anaphylaxis symptoms and treatment.

| Beekeeper aware of anaphylaxis and/or allergic shock (n=38) | Beekeeper unaware of anaphylaxis and/or allergic shock (n=31) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Know the epinephrine auto-injector | 0.004 | ||

| Yes | 17 (44.7%) | 4 (12.9%) | |

| No | 21 (55.3%) | 27 (87.1%) | |

| Know the symptoms of anaphylaxis | 0.096 | ||

| Yes | 34 (89.5%) | 23 (74.2%) | |

| No | 4 (10.5%) | 8 (25.8%) | |

| Encountered anaphylaxis | n/a | ||

| Yes | 22 (57.9%) | – | |

| No | 16 (42.1%) | – | |

| Drugs believed to be life-saving | n/a | ||

| Epinephrine | 14 (57.9%) | 2 (6.5%) | |

| Antihistamines | 4 (13.3%) | – | |

| Antihistamines+systemic corticosteroids | 3 (10.7%) | – | |

| Systemic corticosteroids | 1 (3.6%) | – | |

| Emergency department | 1 (3.6%) | – | |

| Ammonia | – | 1 (3.2%) | |

| Know how to use epinephrine auto-injector | 12 (31.6%) | 1 (3.2%) | n/a |

n/a: non-available.

bold p value: statistically significant.

Of the restaurant staff, 23.1% (n=12) had knowledge about the terms of ‘anaphylaxis’ and/or ‘allergic shock’. Similar to the beekeepers, most of the restaurant staff that were aware of anaphylaxis were significantly familiar with an epinephrine auto-injector. However, unlike the beekeepers, 60% (n=24) of the restaurant staff who were unaware about anaphylaxis had no idea about the potential symptoms. Although none of the restaurant staff had experienced or encountered anaphylaxis by themselves, two of them reported drug-induced anaphylaxis in their family members, (supplementary files).

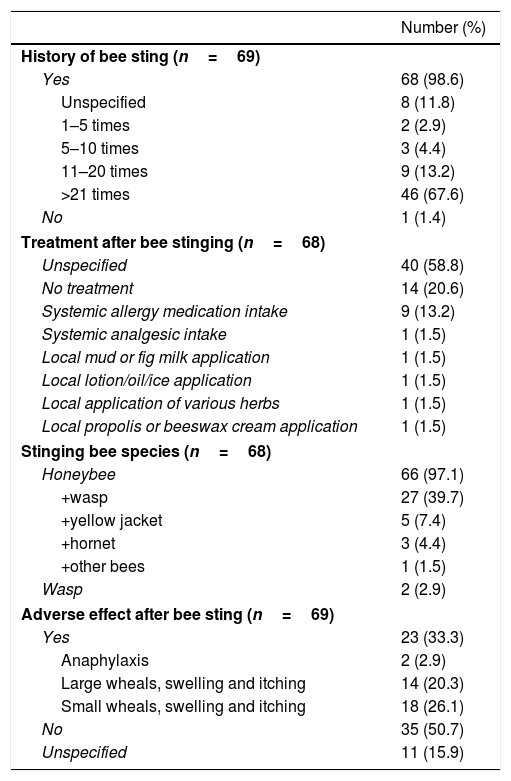

History of bee sting and family history of allergic diseasesAnaphylaxis following a bee sting was reported in 2.9% (n=2) of the beekeepers, in 2.9% (n=2) of the beekeepers’ spouses, and in 2.9% (n=2) of the beekeepers’ children. Interestingly, among the beekeepers who reported that they had never experienced any adverse effect after a bee sting, five of them had already reported having large wheals and six of them had reported having small wheals in the next question of the questionnaire. Data regarding the number of bee stings, species of stinging bees, reactions related to bee stings, and their treatment attitudes are summarized in Table 3.

History of bee sting, types of reaction, and treatment approaches.

| Number (%) | |

|---|---|

| History of bee sting (n=69) | |

| Yes | 68 (98.6) |

| Unspecified | 8 (11.8) |

| 1–5 times | 2 (2.9) |

| 5–10 times | 3 (4.4) |

| 11–20 times | 9 (13.2) |

| >21 times | 46 (67.6) |

| No | 1 (1.4) |

| Treatment after bee stinging (n=68) | |

| Unspecified | 40 (58.8) |

| No treatment | 14 (20.6) |

| Systemic allergy medication intake | 9 (13.2) |

| Systemic analgesic intake | 1 (1.5) |

| Local mud or fig milk application | 1 (1.5) |

| Local lotion/oil/ice application | 1 (1.5) |

| Local application of various herbs | 1 (1.5) |

| Local propolis or beeswax cream application | 1 (1.5) |

| Stinging bee species (n=68) | |

| Honeybee | 66 (97.1) |

| +wasp | 27 (39.7) |

| +yellow jacket | 5 (7.4) |

| +hornet | 3 (4.4) |

| +other bees | 1 (1.5) |

| Wasp | 2 (2.9) |

| Adverse effect after bee sting (n=69) | |

| Yes | 23 (33.3) |

| Anaphylaxis | 2 (2.9) |

| Large wheals, swelling and itching | 14 (20.3) |

| Small wheals, swelling and itching | 18 (26.1) |

| No | 35 (50.7) |

| Unspecified | 11 (15.9) |

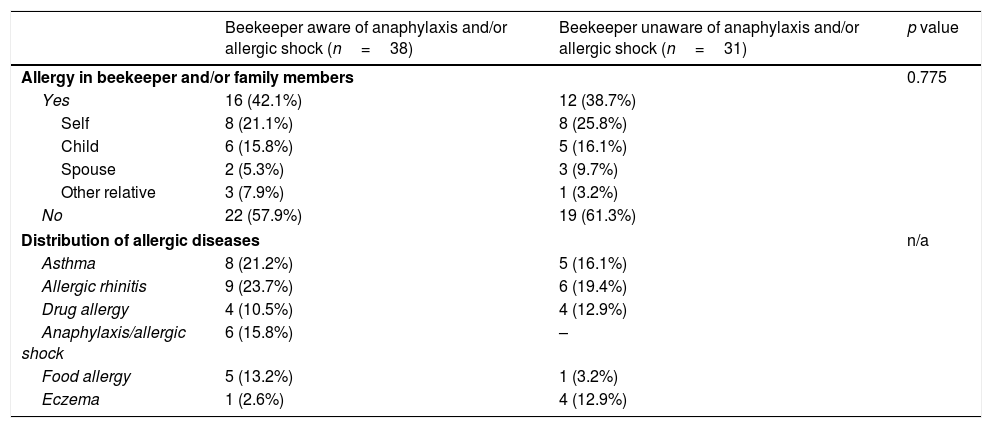

Of the restaurant staff, 63.5% (n=33) had a history of a bee sting without anaphylaxis. Fifteen of them (45.5%) had no adverse effect, six of them (18.1%) had large and 12 of them (36.4%) had small wheals after a bee sting (Supplementary Table 3). Presence of allergic diseases in beekeepers and restaurant staff and/or in their family members were reported by 40.6% (n=28) and 44.2% (n=23), respectively. There was no significant difference in previous history of allergic diseases between the groups, regarding awareness of anaphylaxis. Family history of allergic diseases in beekeepers is presented in Table 4.

Family history and distribution of allergic diseases.

| Beekeeper aware of anaphylaxis and/or allergic shock (n=38) | Beekeeper unaware of anaphylaxis and/or allergic shock (n=31) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Allergy in beekeeper and/or family members | 0.775 | ||

| Yes | 16 (42.1%) | 12 (38.7%) | |

| Self | 8 (21.1%) | 8 (25.8%) | |

| Child | 6 (15.8%) | 5 (16.1%) | |

| Spouse | 2 (5.3%) | 3 (9.7%) | |

| Other relative | 3 (7.9%) | 1 (3.2%) | |

| No | 22 (57.9%) | 19 (61.3%) | |

| Distribution of allergic diseases | n/a | ||

| Asthma | 8 (21.2%) | 5 (16.1%) | |

| Allergic rhinitis | 9 (23.7%) | 6 (19.4%) | |

| Drug allergy | 4 (10.5%) | 4 (12.9%) | |

| Anaphylaxis/allergic shock | 6 (15.8%) | – | |

| Food allergy | 5 (13.2%) | 1 (3.2%) | |

| Eczema | 1 (2.6%) | 4 (12.9%) | |

n/a: non-available.

Previous studies have shown that beekeepers in Turkey practice beekeeping as a continuation of their family profession without a concise training in beekeeping.15,16 In contrast, beekeeping was not the primary family profession in our study population, and most of those beekeepers were well educated, predominantly with an undergraduate degree. It may be speculated that well-educated beekeepers tend to attend such congresses more frequently than un-educated counterparts. Having a training of beekeeping did not make any significant difference between the groups regarding awareness about anaphylaxis. This may highlight that education about anaphylaxis should be included in beekeeping training programs.

The reported incidence of bee sting-induced anaphylaxis is higher among beekeepers compared to the general population.13,14 Our results are compatible to previous reports. Beekeepers are more prone to experience anaphylaxis due to frequent stinging, so it is not surprising that they are more knowledgeable about anaphylaxis than restaurant staff. In parallel to previous reports, our results have shown that restaurant staff's awareness about anaphylaxis and auto-injector was very low, which may be attributed to the low incidence of food-induced anaphylaxis among the general population.17–19

Awareness of anaphylaxis and epinephrine auto-injectors was less common among beekeepers who had never encountered anaphylaxis in their near surroundings. Nevertheless, about 75% of the group who are unaware of anaphylaxis could successfully identify the symptoms, and all of them correctly answered that there might be accompanying respiratory symptoms. Similarly, there were some beekeepers who had heard of and knew how to use an epinephrine auto-injector among the group that were unaware of anaphylaxis. This suggests that even though they may not know the terms of ‘anaphylaxis’ and/or ‘allergic shock’, among that group, some of the beekeepers might have encountered anaphylaxis and might have referred it by another name. Although there are numerous reports about venom allergy in beekeepers,20–24 there have been few studies investigating levels of knowledge about anaphylaxis and epinephrine autoinjectors. In a study by Ediger et al., 82.8% of beekeepers were aware that bee stings can be fatal, while only 38.6% knew about epinephrine auto-injectors.25 Another study reported that 10.6% of beekeepers had heard of the epinephrine auto-injector.26 In our study, 30.4% of the beekeepers were familiar with epinephrine auto-injectors. Despite being aware of the epinephrine auto-injector, some of the beekeepers suggested that antihistamines and/or systemic corticosteroids were life-saving treatments. This has pointed out that the knowledge of correct treatment for anaphylaxis and awareness about epinephrine auto-injectors must be popularized among the beekeepers.

It is also known that in several parts of Turkey, bee stings are sometimes treated with several folk remedies.25,26 In our study 5.8% of the beekeepers have reported that they also used some alternative remedies like applying ammonia, beeswax cream, propolis, various herbs, lotion, oil, mug and fig milk.

The presence of atopic diseases may increase the risk of systemic reaction incidence as described previously.13,21,22,27 There were two beekeepers who self-reported anaphylaxis in our study population. One of them had coexisting asthma and allergic rhinitis, whereas the other had no history of allergic disease.

Despite answering that there was no adverse reaction after a bee sting, most of the beekeepers subsequently reported that they had developed ‘small or large wheals’, in the following question. This suggests that those beekeepers did not assume swelling as a serious problem, regardless of its size.28

In our study, the rate of self-reported anaphylaxis after bee sting among beekeepers was similar to previous reports.13,21 The rate of bee-sting induced anaphylaxis among the family members of beekeepers was 5.8%, which might be attributed to the risk of frequent exposure to bee stings.20

ConclusionVenom allergy can be fatal and is a major occupational hazard associated with beekeeping. Therefore, beekeepers and their families must be trained about anaphylaxis. We believe that focused training programs and availability of epinephrine auto-injectors may decrease preventable future morbidities and mortalities.

Clinical Implications: Venom allergy is a potentially life-threatening allergic reaction and beekeepers and their family members are at an increased risk of anaphylaxis. It is essential that focused training programs about anaphylaxis symptoms and signs as well as practical instructions of when and how to use an epinephrine auto-injector will decrease preventable morbidities and mortalities in high-risk occupations.

FundingThis study received no financial support from any institution or individual.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest related to the study described in this manuscript.