Eosinophilic oesophagitis (EoE) is a disorder characterised by oesophageal dysfunction and, histologically, by eosinophilic inflammation. Although treatment, which includes dilatations, oral corticosteroids and restrictive diets, is often effective, choosing the foods to be eliminated from the diet is difficult.

ObjectiveComponent resolved diagnostic by microarray allergen assay may be useful in detecting allergens that might be involved in the inflammatory process.

MethodsWe studied 67 patients with EoE, diagnosed clinically and histologically by endoscopic biopsy. CRD analysis with microarray technology was carried out in the 67 EoE patients, 50 patients with pollen allergy without digestive symptoms, and 50 healthy controls.

ResultsAllergies were not detected by microarray in only seven of the 67 patients with EoE. Controls with pollen allergy showed sensitisation to different groups of pollen proteins without significant differences. In EoE patients with response to some allergens, the predominant allergens were grasses group 1 and, in particular, nCyn d 1 (Cynodon dactylon) or Bermuda grass pollen in 59.5%, followed by lipid transfer proteins (LTP) of peach (19.40%), hazelnut (17.91%) and Artemisia (19.40%).

ConclusionsIn patients with EoE, sensitisation to plant foods and pollen is important. The proteins most frequently involved are nCyn d 1 and lipid transfer proteins, hazelnuts and walnuts. After one year of an array-guided exclusion diet and pollen-specific immunotherapy in the case of high levels of response, patients with EoE showed preliminary significant improvements.

Eosinophilic oesophagitis (EoE) is an atopic disease of the oesophagus whose diagnosis has been increasing over the last decade. Accumulating animal and human data have provided evidence that EoE appears to be an antigen-driven immunologic process that involves multiple pathogenic pathways; so a conceptual definition is proposed highlighting that EoE represents a chronic, immune/antigen-mediated disease characterised clinically by symptoms related to oesophageal dysfunction and histologically by eosinophil-predominant inflammation.1

EoE occurs in both children and adults worldwide. It affects 1 in 2500 people in both USA and EU, but its incidence is increasing. The diagnosis is based on clinical symptoms and histological findings (predominantly eosinophilic inflammation).1–5 Apart from severe choking, inflammation of the oesophagus may have severe systemic and emotional repercussions for patients and their families. Some patients exhibited histological remission after proton pump inhibitor (PPI) treatment.6 Unlike gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GERD), whose symptoms overlap with oesophagitis, EoE is often due to allergen hypersensitivity that may be improved with diet control if the food implicated is clearly known.6,7

There are results for different therapeutic options, which, although not providing a definitive cure for the disease, are effective in providing and maintaining disease remission. However, to date, no reliable, risk-free diagnostic technique for EoE has yet been found.

Symptomatic treatments of EoE include the Six-Food Elimination Diet (SFED),2–5 oral corticosteroids, leukotriene modifiers and palliative measures such as mechanical dilation of the oesophagus. Empirical elimination of foods has so far been the most effective therapeutic measure but requires multiple control endoscopies and can significantly hinder quality of life. A definitive aetiological diagnosis would be fundamental in determining the specific allergens which cause eosinophilic inflammation of the oesophageal mucosa and which foods should be avoided.

There have been no randomised studies designed to find the real causes and specific measures required to prevent EoE.8–12 Routine allergic techniques (prick tests) and determination of IgE have a poor predictive value for food allergens in EoE.13

Although the international consensus document for diagnosis or therapeutic management of EoE1 establishes demonstration of disease recrudescence after food reintroduction, provocation techniques with foods are very hard in EoE, especially in multi-sensitised patients.14,15

According to consensus guidelines for managing EoE in children and adults, allergy test results by themselves cannot be used to make a diagnosis of EoE food triggers, which only can be achieved after documented disease remission upon food restriction and recrudescence when reintroduction. As a result, restrictions in diets should not be recommended to EoE patients exclusively on the basis of positive test results.

Nevertheless, it is difficult to choose what foods should be excluded from diet and a restrictive diet of six principal foods is complicated to follow for a long time.

Recently, it has become possible to measure IgE antibodies to specific allergen molecules, a method called “component resolved diagnostics” (CRD). For aeroallergens, CRD has shown a good correlation with classic IgE assays in multi-sensitised patients and allows 112 IgE measures to be obtained with a very small volume of sera.

It would be of interest to complete diagnostic tests with molecular analysis of all the proteins involved in hypersensitivity to allow better-targeted dietary restrictions or, when this is not possible, to try a specific, safe hyposensitising treatment. We used the microarray technique, based on micro-immunoassays, which, in the case of the Thermofisher® panel, allow testing of 112 allergenic native and recombinant components, to obtain a more specific and complete profile of sensitisation to food allergen hypersensitivity.16,17 In addition to foods, the panel includes environmental allergens that have not been tested in EoE patients, but could prove to be important, since many allergens, such as pollen, are swallowed after reaching the oropharynx.

The general aim of our study was to evaluate IgE-mediated allergic hypersensitivity to various food and environmental allergens (native and recombinant) in EoE affected population.

The specific objectives were as follows:

- 1.

To evaluate the incidence of the IgE-mediated response to foods and aeroallergens in patients with EoE, patients with pollen allergy, and healthy controls.

- 2.

Evaluate the value of CRD analysis by microarrays in the management of EoE.

This was a cross-sectional study. Patients were included and the analyses made between 15 November 2011 and May 2013. We randomly selected 67 consecutive patients attending the hospital's facilities diagnosed with EoE by the Department of Gastroenterology, Hospital Universitario Rio Hortega (HURH). These patients were recruited over two years avoiding the pollination period (May–July in our area). All patients were assessed in the same time frame, in order to avoid selection bias, since allergy test results may vary according to current exposition.

Fifty asthmatic patients with allergy to pollen were also randomly selected from a database of 23,873 patients seen in the last 23 years by the HURH Allergy Clinic. The inclusion criteria were usual residence in Valladolid or province, either sexes, living in the same house or area from birth, and fulfilment of similar criteria of clinical severity of asthma. Asthma was defined as dyspnoea due to variable airflow obstruction with no other demonstrable cause or coughing for three consecutive nights and sleep disorders from six months of age (ISAAC criteria).

We also randomly selected 50 non-smoking, healthy controls without gastrointestinal or atopic symptoms, who had never attended our Allergy Clinic, from among blood donors of the SACYL Blood Donation Unit.

Exclusion criteria were birth in another area, or residence in another area.

Sensitisation to pollen was defined as the presence of (a) one or more positive skin tests to pollen; (b) a CAP (IgE) titres >0.35IU/mL to pollen; and (c) positive specific provocation. Grass pollen asthma was defined by prick, specific IgE and spirometric criteria. Ryegrass pollen (Lolium perenne) was chosen as the measurable parameter as it is the most widely found grass pollen allergy in our region.

All patients were studied using the same diagnostic tests. All patients were considered to have been exposed to similar levels of pollen, pollution and other environmental factors, as confirmed by analysis of environmental quality standards made weekly by the Environmental Health Control Section of the Ministry of Health of our region (SACYL). All patients followed a standard Mediterranean diet, verified by nutritional surveys.

Evidence in vivoSkin testsPrick tests were carried out in accordance with the standards of the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI). After placing a drop of each test allergen on the volar area of the forearm, minimal puncture, which should not reach the dermis, was made using a lancet. The excess extract was removed and the result was read after 15min. A positive test was when a wheal with a diameter ≥3mm was produced. Each allergen was tested in duplicate and the results were recorded on a data collection sheet for subsequent digitisation.

Allergen extractsA standard battery of aeroallergens and foods was used, including pollens (Gramineae, trees, weeds and flowers), mites (Dermatophagoides and storage mites), fungi, animal and common food antigens, including fractionated batteries of antigens of milk, egg white and yolk, nut, fish, shellfish, Anisakis, legumes and fruits (ALK-Abelló, Madrid, Spain).

Negative and positive controls were composed of phenolated and glycerinated saline solution and histamine at 10mg/mL, respectively. The wheal area was measured at 15min. When the mean wheal area was calculated, a dose–response graph representing these values against the logarithm of the concentration of allergen tested was constructed. The mean area caused by a positive reference (histamine–HCl) was obtained for bounded concentrations of the allergen.

Patients suffering from EoE and grass pollen hypersensitivity and pollinic patients were treated with conventional immunotherapy depot, ALK-Abelló, Denmark, for one year.

In patients with EoE, endoscopy and biopsy were carried out after each six months of specific immunotherapy and dietary exclusion treatment. Biopsy was considered compatible with eosinophilic oesophagitis if there were >15 eosinophils per field.

In vitro testsSpecific IgESpecific IgE was determined for a battery of aeroallergens and foods: wheat, barley and rye, milk, alpha-lactalbumin, beta-lactoglobulin, casein, egg white and yolk, fish, shellfish and Anisakis and plant foods (vegetables, legumes, nuts, fresh fruits, tobacco, latex, tomatoes) using the FEIA-CAP system (Thermofisher®, Uppsala, Sweden). Levels of IgE>0.35kU/L (mean: 16.3kU/L, range 0.51–100kU/L) were considered positive.

Molecular analysis by microarray was made using the ISAC technique (Thermofisher®, Uppsala, Sweden), following the manufacturer's instructions. A determination of >0.3 ISU was considered positive.

EvolutionWhen microarray showed sensitisation to a food allergen, the specific food involved was withdrawn. Conventional specific immunotherapy was prescribed in the case of important sensitisation to pollen, even when symptoms were not respiratory. In patients with EoE, endoscopy and biopsy were carried out after each six months of specific immunotherapy and dietary exclusion treatment. Biopsy was considered compatible with eosinophilic oesophagitis if there were >15 eosinophils per field. These patients with EoE and grass pollen hypersensitivity and allergic patients will be treated with conventional immunotherapy depot, ALK-Abelló, Denmark for one year. Patients will be considered to have a favourable evolution if one year after the initial intervention, clinical signs and symptoms have improved or disappeared and the oesophageal biopsy is normal.

Quality of Life Questionnaire (AQLQ) and diary record were used to assess quality of life, number and severity of symptoms, and the dosage of the medication required at baseline and after six and 12 months.

Ethical considerationsAll patients provided signed informed consent and the study was approved by the Clinical Trials Committee of HURH Hospital.

Statistical analysisQuantitative variables were described using the mean, standard deviation, and confidence interval of the mean, or the median and interquartile range and minimum and maximum values for data without a Gaussian distribution.

The distribution of categorical variables was described using absolute frequencies and percentages.

The graphic description of categorical variables was made using box and whiskers plots. To test the normality of distribution of sample <30, we used the Shapiro–Wilks or Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests.

To detect statistically significant relationships between categorical variables and evaluate the evolution after treatment the Chi-square test or Fisher's exact test were used as required.

When statistically significant differences were found for variables with more than two categories, the Bonferroni and Hochberg corrections were used in a posteriori pair comparisons. Logistic regression models were used to determine the influence of different allergens on the evolution of EoE, corrected by the different patient groups. The statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS v15.0 statistical package.

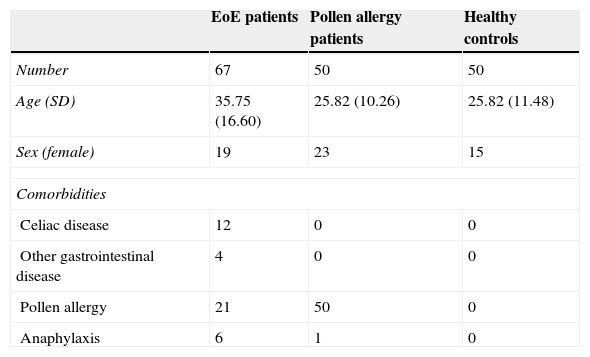

ResultsThe mean age of the study cohort was 31.54±14.02 years and 66% were males. The sociodemographic and clinical variables of the three groups at baseline are shown in Table 1. The mean age was 35.7±16.6 years in patients with EoE, 25.82±10.26 in patients with asthma, and 31.62±11.48 in controls. The only significant difference in sociodemographic variables was that patients with asthma were younger than patients with EoE (p>0.001).

Sociodemographic and clinical variables at baseline.

| EoE patients | Pollen allergy patients | Healthy controls | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 67 | 50 | 50 |

| Age (SD) | 35.75 (16.60) | 25.82 (10.26) | 25.82 (11.48) |

| Sex (female) | 19 | 23 | 15 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Celiac disease | 12 | 0 | 0 |

| Other gastrointestinal disease | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Pollen allergy | 21 | 50 | 0 |

| Anaphylaxis | 6 | 1 | 0 |

A high rate of sensitisation to aeroallergens and food allergens was present in patients who suffered from EoE.

Allergies were not detected by microarray in only seven of the 67 patients with EoE. Controls with pollen allergy showed sensitisation to different groups of pollen proteins without significant differences among these pollen groups. By contrast, in EoE patients with response to some allergens, the predominant allergens were grasses group 1 and, in particular, nCyn d 1 (Cynodon dactylon) or Bermuda grass pollen in 59.5%, followed by lipid transfer proteins (LTP) of peach (19.40%), hazelnut (17.91%), and Artemisia (19.40%).

After performing prick and specific IgE in all patients, two patients from the healthy group presented low levels of positivity to pollen and Anisakis. They have never had atopic symptoms. These healthy controls without gastrointestinal or atopic symptoms who had never attended our Allergy Clinic, were selected from among blood donors of the SACYL Blood Donation Unit, which rejects donations from patients affected by allergies or infectious diseases. Until microarray results, which detected more positive results we had no way of knowing that these patients had some atopic conditions. They were informed about these results and re-evaluated. Only the patients sensitised to Anisakis and kiwi remembered previous symptoms and the food was removed from their diet.

With respect to comorbidities, 12 (17.9%) of the EoE patients had celiac disease, compared with none in the other two groups. There was no association with other intestinal or atopical respiratory diseases.

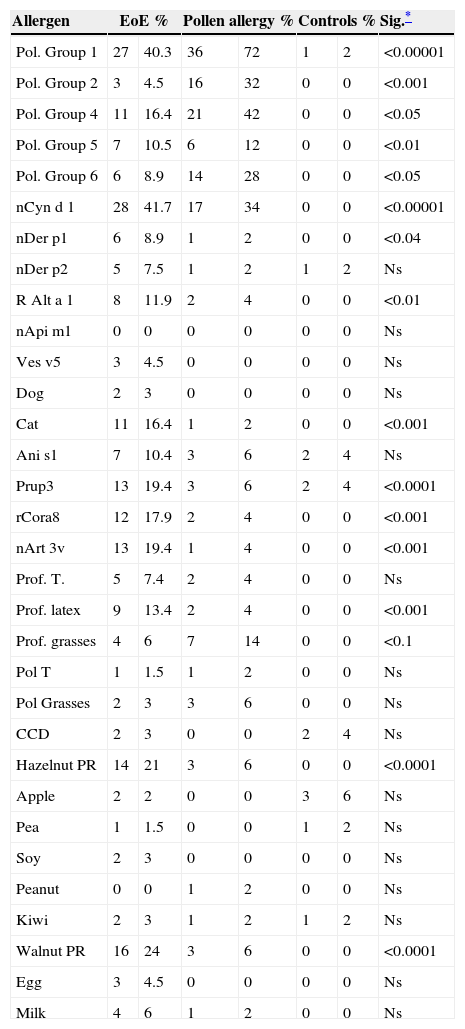

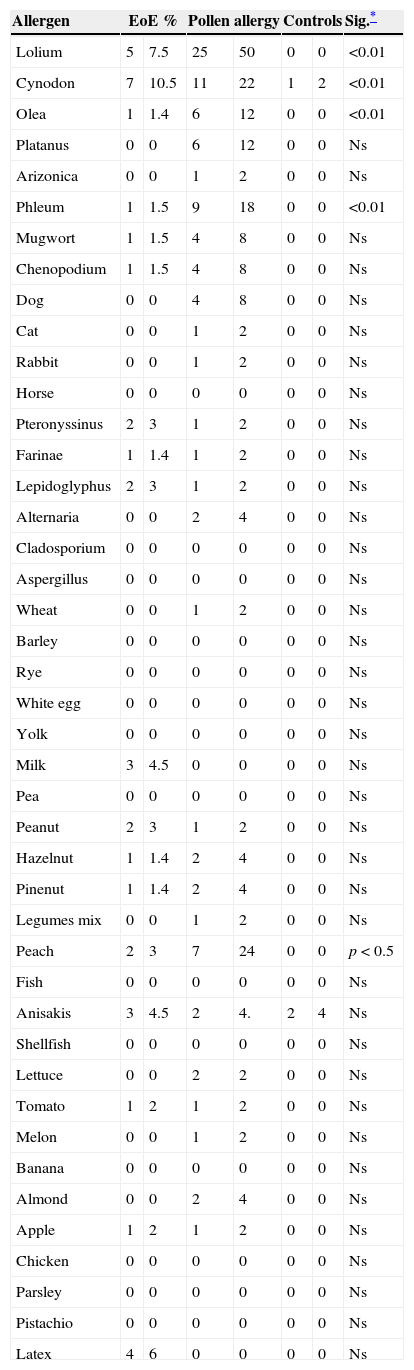

Tables 2 and 3 show results of sensitisation to native and recombinant allergens measured by array techniques and determination of IgE to allergens by CAP. Array techniques detected significantly more allergen positivity compared with prick tests and IgE by CAP (p<0.001) (Table 4).

Positive results for main allergens measured by microarray according to study group.

| Allergen | EoE % | Pollen allergy % | Controls % | Sig.* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pol. Group 1 | 27 | 40.3 | 36 | 72 | 1 | 2 | <0.00001 |

| Pol. Group 2 | 3 | 4.5 | 16 | 32 | 0 | 0 | <0.001 |

| Pol. Group 4 | 11 | 16.4 | 21 | 42 | 0 | 0 | <0.05 |

| Pol. Group 5 | 7 | 10.5 | 6 | 12 | 0 | 0 | <0.01 |

| Pol. Group 6 | 6 | 8.9 | 14 | 28 | 0 | 0 | <0.05 |

| nCyn d 1 | 28 | 41.7 | 17 | 34 | 0 | 0 | <0.00001 |

| nDer p1 | 6 | 8.9 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | <0.04 |

| nDer p2 | 5 | 7.5 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | Ns |

| R Alt a 1 | 8 | 11.9 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0 | <0.01 |

| nApi m1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Ns |

| Ves v5 | 3 | 4.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Ns |

| Dog | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Ns |

| Cat | 11 | 16.4 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | <0.001 |

| Ani s1 | 7 | 10.4 | 3 | 6 | 2 | 4 | Ns |

| Prup3 | 13 | 19.4 | 3 | 6 | 2 | 4 | <0.0001 |

| rCora8 | 12 | 17.9 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0 | <0.001 |

| nArt 3v | 13 | 19.4 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | <0.001 |

| Prof. T. | 5 | 7.4 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0 | Ns |

| Prof. latex | 9 | 13.4 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0 | <0.001 |

| Prof. grasses | 4 | 6 | 7 | 14 | 0 | 0 | <0.1 |

| Pol T | 1 | 1.5 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | Ns |

| Pol Grasses | 2 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 0 | 0 | Ns |

| CCD | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 4 | Ns |

| Hazelnut PR | 14 | 21 | 3 | 6 | 0 | 0 | <0.0001 |

| Apple | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 6 | Ns |

| Pea | 1 | 1.5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | Ns |

| Soy | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Ns |

| Peanut | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | Ns |

| Kiwi | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | Ns |

| Walnut PR | 16 | 24 | 3 | 6 | 0 | 0 | <0.0001 |

| Egg | 3 | 4.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Ns |

| Milk | 4 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | Ns |

Groups 1, 4, 5 and 6 of pollens: (Pol. Group 1, 4, 5, 6).

nCyn d 1: Group 1 of Cynodon dactylon (Bermuda grass pollen); nDer p1 and Der p2: Cysteine-proteases of Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus and farinae respectively.

R Alt a 1: acidic glycoprotein of Alternaria alternata; nApi m1: phospolypase A2 of apis venom; Ves v5: phospolypase A2 of yellow jacket venom; rAni s 1: serine-protease inhibitor of Anisakis simplex; nPrup3: peach lipid transfer protein; rCor a 8: hazelnut lipid transfer protein; nArt v3: mugwort lipid transfer protein; Prof T: tree pollen profilin; Prof G: grasses pollen profilin; Prol T: tree pollen polcalcin; Prof G: grasses pollen polcalcin; CCD: cross-reactivity carbohydrate determinants.

Prick/IgE against the allergens tested by study group.

| Allergen | EoE % | Pollen allergy | Controls | Sig.* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lolium | 5 | 7.5 | 25 | 50 | 0 | 0 | <0.01 |

| Cynodon | 7 | 10.5 | 11 | 22 | 1 | 2 | <0.01 |

| Olea | 1 | 1.4 | 6 | 12 | 0 | 0 | <0.01 |

| Platanus | 0 | 0 | 6 | 12 | 0 | 0 | Ns |

| Arizonica | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | Ns |

| Phleum | 1 | 1.5 | 9 | 18 | 0 | 0 | <0.01 |

| Mugwort | 1 | 1.5 | 4 | 8 | 0 | 0 | Ns |

| Chenopodium | 1 | 1.5 | 4 | 8 | 0 | 0 | Ns |

| Dog | 0 | 0 | 4 | 8 | 0 | 0 | Ns |

| Cat | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | Ns |

| Rabbit | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | Ns |

| Horse | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Ns |

| Pteronyssinus | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | Ns |

| Farinae | 1 | 1.4 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | Ns |

| Lepidoglyphus | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | Ns |

| Alternaria | 0 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0 | Ns |

| Cladosporium | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Ns |

| Aspergillus | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Ns |

| Wheat | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | Ns |

| Barley | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Ns |

| Rye | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Ns |

| White egg | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Ns |

| Yolk | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Ns |

| Milk | 3 | 4.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Ns |

| Pea | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Ns |

| Peanut | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | Ns |

| Hazelnut | 1 | 1.4 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0 | Ns |

| Pinenut | 1 | 1.4 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0 | Ns |

| Legumes mix | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | Ns |

| Peach | 2 | 3 | 7 | 24 | 0 | 0 | p<0.5 |

| Fish | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Ns |

| Anisakis | 3 | 4.5 | 2 | 4. | 2 | 4 | Ns |

| Shellfish | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Ns |

| Lettuce | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | Ns |

| Tomato | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | Ns |

| Melon | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | Ns |

| Banana | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Ns |

| Almond | 0 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0 | Ns |

| Apple | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | Ns |

| Chicken | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Ns |

| Parsley | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Ns |

| Pistachio | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Ns |

| Latex | 4 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Ns |

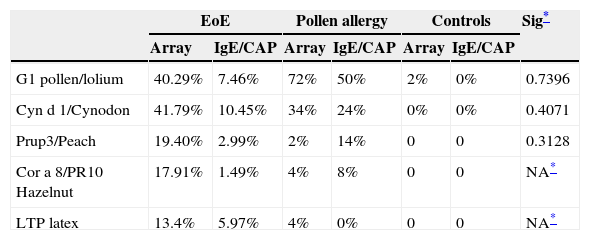

Response to main allergens by study group.

| EoE | Pollen allergy | Controls | Sig* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Array | IgE/CAP | Array | IgE/CAP | Array | IgE/CAP | ||

| G1 pollen/lolium | 40.29% | 7.46% | 72% | 50% | 2% | 0% | 0.7396 |

| Cyn d 1/Cynodon | 41.79% | 10.45% | 34% | 24% | 0% | 0% | 0.4071 |

| Prup3/Peach | 19.40% | 2.99% | 2% | 14% | 0 | 0 | 0.3128 |

| Cor a 8/PR10 Hazelnut | 17.91% | 1.49% | 4% | 8% | 0 | 0 | NA* |

| LTP latex | 13.4% | 5.97% | 4% | 0% | 0 | 0 | NA* |

Comparison of the mean positive results for arrays, prick and IgE (CAP) in the three groups, using the odds ratio to assess whether the risk of having positive IgE and prick tests differed between groups. After applying the Breslow–Day test to measure the homogeneity of the odds ratio, we found that molecular analysis using microarray had a greater yield than the prick test or IgE-CAP in obtaining a diagnosis of allergenic hypersensitivity and was significantly more useful (p<0.0001) in detecting sensitisation to grass group 1, Cyn d 1 and LTP (Table 4).

Logistic regression was used to determine the influence of sensitivity to a specific allergen on the final outcome. This showed that patients with EoE and pollen allergy had an odds ratio >1 (CI 95%) significantly higher than that of patients without pollen allergy.

In addition, patients sensitive to Lolium perenne had a worse outcome than those who were not (p=0.004).

The effect of one year elimination diet on the eosinophilic infiltration and clinical evolution of EoE patients who underwent a microarray testing-directed food elimination were favourable but we are now compiling data to analyse the effectiveness of the measures taken.

Preliminary results show that patients with EoE with a positive response to grass pollen have better outcomes than patients with EoE without a positive response.

Our patients improved after exclusion of the food detected in microarrays and pollen-specific immunotherapy when there was a high level of response to these allergens.

Sixteen per cent of patients with EoE and 28% of patients with asthma had a negative evolution (no improvement in symptoms or eosinophilic inflammation on biopsy) after diet and directed immunotherapy. Logistic regression to determine the influence of sensitivity to a specific allergen on the final outcome suggests that patients with EoE and pollen allergy have an odds ratio >1 for a favourable evolution, significantly higher than that of EoE patients without pollen allergy.

DiscussionEosinophilic oesophagitis (EoE) is a disorder characterised by oesophageal dysfunction and, histologically, by eosinophilic inflammation.1 Eosinophilic infiltration can also be found in other immune digestive diseases: gastrointestinal disease in children is associated with foodstuffs and is normally resolved after the identification and elimination of the agents involved, but this identification is very difficult using current allergen identification techniques and children may be subjected to dietary restrictions that hinder development.

Patients diagnosed with reflux may actually have oesophagitis of immune origin. Both conditions (EoE and reflux) may have an increase in lymphocytes, and both conditions may be characterised by eosinophils. There is no discussion about treatment with proton pump inhibitors in their patients to help distinguish reflux from EoE in their patient population.6,7

Allergy and food intolerance must also be differentiated. Recent epidemiological studies show food allergy in children has increased, with the most frequent allergens being egg, milk, nuts, wheat, soy and seafood.8

Nevertheless the origin of EoE is unknown but genetic alterations in eotaxin 3 abnormal thymic lymphopoietin, IL13 and filaggrin alterations that may contribute to the development of EoE have been identified.10 An increasing body of knowledge shows that a delayed cell-mediated hypersensitivity response is predominant in the pathogenesis of EoE, instead of an IgE-mediated allergy. This fact has added more controversy to the actual role that IgE-based allergy testing plays in the pathophysiology of EoE, a distinct disease that frequently appears in patients with associated atopic disorders, each one responding to different intimate mechanisms.1–7

On the other hand it has been suggested that an allergic mechanism plays a role in the pathophysiology of EoE, although the exact allergens are unknown.2

Very recently, an association between eosinophilic oesophagitis (EoE) and celiac disease (CD) has been suggested.19 However, this association may be limited to paediatric patients, where the risk of each condition is increased 50–75-fold in patients diagnosed with the alternative condition. Our results showed a high level of coexistence between EoE and celiac disease in adults. The concomitant diagnosis of these conditions should be considered in patients with upper gastrointestinal symptoms.

In EoE a history of atopy or allergy can be found and involves foods in most EoE cases, so exposition to aeroallergens like pollens looked to play an aetiological role in only a minority of EoE patients. Swallowing pollen may be a mechanism, as there is the possibility (as demonstrated by many of the animal models) that tracheal or lung sensitisation from airborne allergens triggers oesophageal eosinophilia (but not fed antigen). The high remission rates that have been repeatedly demonstrated for exclusively feeding with elemental diet in children and also recently in adults, which are >95%, involve foods in most of EoE cases. Nevertheless, in adults with EoE, sensitisation to aeroallergens seemed to be also prevalent.

In summary, the exact mechanism of EoE in humans remains unknown. In order to know whether atopic diseases such as pollen allergy are an epiphenomenon and not actually causal in EoE requires more studies to be carried out.15,16,20–22

Allergy test results by themselves cannot be used to make a diagnosis of EoE food triggers, which can only be achieved after documented disease remission upon food restriction and recrudescence on reintroduction. Our study also shows that prick test and specific IgE detection by routine methods do not optimally identify the cause.10,15

Provocation techniques with foods are very hard in EoE, especially in multi-sensitised patients.14,15

Recently it has become possible to measure IgE antibodies to specific allergen molecules, using a method called component resolved diagnostics (CRD). For aeroallergens, CRD has shown a good correlation with classic IgE assays in multi-sensitised patients. The strengths of CRD are that it provides patient-tailored results and that it enables discrimination between genuine allergy and cross-reactivity to allergens, and a microarray assay format has made it possible to test for a large number of allergens.

We have found that allergies were not detected by microarray in only seven of the 67 patients with EoE. The results of our study show that sensitisation to airborne allergens and plant foods, specifically pollens, are prevalent in patients with EoE.

Array techniques showed that the proteins most frequently involved are allergens from grasses and LTPs (associated with a severe clinical pattern), followed by hazelnut and walnut allergens. The predominant allergens in our adult patients who suffered from EoE were grasses group 1 and, in particular, nCyn d 1 (Cynodon dactylon) or Bermuda grass pollen in 59.5%. Grass group1 are ¿-expansins with a molecular weight of 31–35kDa, which are involved in the relaxation of plant cell membranes and in growth. Cynodon Cyn d 1 has antifungal function against claviceps, a source of alkaloids (ergonovine and ergonovinine), causing tremorgenic syndrome in cattle due to Cynodon consumption.18

Although we do not have efficacy data yet, microarray results have been useful in deciding what food to exclude from a diet and to try more specific immunotherapy in patients with high sensitisation to pollen. Allergy desensitisation therapy should be very interesting and is not yet described as a treatment for EoE. There is a lack of randomised control trials, and further analysis will be necessary. We will plan a randomised controlled trial of desensitisation in EoE patients – one group receives immunotherapy for what they are allergic to, and the other group receives a sham therapy.

Quantification of IgE antibodies against specific allergen components and as components of cross-reactivity has helped to identify the sensitising allergen source. In addition we have measured response to other allergens from different origins and assessed the response due to cross-reactivity with other plant and animal proteins (profilin, cross-reactive carbohydrates, polcalcins, tropomyosins, etc.), which cause cross-reactivity and create diagnostic problems.

In conclusion, the possibility of multiple measurement of more than over 100 IgE allergenic epitopes (native and recombinant) using a microarray technique has been a useful, simple and non-invasive form of diagnosing these patients with complex sensitisation. These tests may be effective in characterising sensitisation profiles and providing a basis for directed and, possibly, efficacious targeted exclusion diet and specific immunotherapy.

FundingThis work was subsidised by the General Direction of Public Health, Sanidad Castilla y León (SACYL) Valladolid, Spain and registered in its database as GRS 447/A/13.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human subjects and animals in researchThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.

Conflict of interestThe authors have not conflicts of interest.

We sincerely thank our patients, for their courage and interest and Fernando de la Torre for technical support. The authors thank David Buss for his editorial assistance.