The aim of the current study is to evaluate the prevalence, severity and possible risk factors of systemic reactions (SRs) to subcutaneous allergen immunotherapy (SCIT) in children and adolescents with asthma in Hangzhou, east China's Zhejiang province.

MethodsFrom January 2011 to December 2016, this survey analysed the SCIT-related SRs involving 429 patients (265 children and 134 adolescents) affected by allergic asthma. Recorded data included demographics, diagnosis, patient statuses, pulmonary function testing results before and after each injection, allergen dosage, and details of SRs.

ResultsAll patients finished the initial phase and six patients withdrew during the maintenance phase. There were 2.59% (328/12,655) SRs in all injections (3.28% in children and 1.47% in adolescents); 15.62% (67/429) patients experienced SRs (18.49% children and 10.98% adolescents). There were 54.57% SRs of grade 1; 42.37% SRs of grade 2; 3.05% SRs of grade 3; and no grades 4 or grade 5 SRs occurred in patients. Most reactions were mild, and were readily controlled by immediate emergency treatment. There was no need for hospitalisation. The occurrence of SRs was significantly higher in children than that in adolescents (p<0.01). A higher ratio of SRs was found among patients with moderate asthma.

ConclusionThis retrospective survey showed that properly-conducted SCIT was a safe treatment for children and adolescents with asthma in Hangzhou, East China. Children and patients with moderate asthma may be prone to develop SRs.

Asthma is one of the most prevalent respiratory conditions, representing some of the most common and costliest conditions in the world. The prevalence of allergic asthma has increased in the last decades.1,2 In subtropical latitudes, most individuals with allergy are sensitised to house dust mites (HDMs).3 HDMs constitute a major, persistent source of indoor aeroallergens and constitute the leading cause of respiratory allergies such as allergic rhinitis (AR) and allergic asthma. These conditions affect more than 500 million people worldwide.4

To date, allergic asthma treatment includes allergen avoidance, pharmacotherapy and allergen specific immunotherapy (AIT). Drugs, such as inhaled corticosteroids, long-acting beta agonists and montelukast, can powerfully control the inflammation, alleviate symptoms and restore respiratory functions. However, pharmacotherapy only treats the symptoms or inflammation and cannot modify the natural history of disease.5

AIT is currently a key part of the allergic asthma management prevention strategy of the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA). It is effective in reducing the clinical symptoms associated with allergic asthma and the only available treatment method that addresses the causes of asthma.1 Subcutaneous immunotherapy (SCIT) and sublingual immunotherapy are the two most prescribed routes for administering AIT. SCIT is now widely used in the management of allergic diseases, including allergic asthma. In the meta-analysis carried out by Ross et al.,6 24 prospective, randomised studies involving 962 asthmatic patients were evaluated. They reported significant amelioration in symptoms and drug intake related with asthma as well as in pulmonary function in the SCIT group in comparison to the placebo. It was deduced that immunotherapy was beneficial in 17 (71%) studies, ineffectual in four (17%) studies, and equivocal in three (12%) studies. Similar to the previous meta-analyses, the authors concluded that SCIT is effective in patients suffering from allergic asthma.7

However, SCIT is associated with a risk of systemic reaction (SRs), which may be severe or even life threatening. Risk factors for SRs that have been identified include type of extract, treatment regimen, patients, administration errors, and seasonal exacerbation of symptoms.8–10 SCIT has been applied for more than 50 years in China; however, there were few reports on the safety of SCIT in children and adolescents. In China, dust mite allergen vaccine (Alutard SQ, Horsholm, Denmark) is the only available standardised product. In this retrospective study, we evaluated the prevalence of SRs of standardised SCIT with the vaccine based on the European house-dust mite (Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus, Dp; Alutard) in Hangzhou east China's Zhejiang province.

Materials and methodsPaediatric patients were children (5–11 years old) and adolescents (12–17 years old). They were recruited from the outpatient allergy clinic of The Children's Hospital Zhejiang University School of Medicine. Patients enrolled in this study were those who: were diagnosed with allergy asthma according to the GINA guidelines; showed positive skin prick test to Dp; and serum Dp-specific IgE levels ≥class 2 had allergic symptoms that could be attributable to mites. All patients met all the three criteria.

Skin tests for 19 kinds of inhalant allergens were performed, including dust mites (Dp and Dermatophagoides farina), cockroach, mulberry silk, animal dander (cat, dog, sheep, and horse), tree pollens (Sabina, Platanus, Populus, and cryptomeria), weed pollens (Artemisia, Ambrosia, and Humulus), and fungi (Alternaria, Cladosporium, Aspergillus, and Paecilomyces) (Macro-Union Pharmaceutical, Beijing, China). Histamine (10mg/mL) and diluent were used as positive and negative controls. Serum specific IgEs were measured by ImmunoCAP (Phadia, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Uppsala, Sweden).

An asthma severity score was used to classify the patients’ asthma as mild, moderate, or severe based on the criteria of Zureik and Ronchetti et al.11,12 Briefly, scores took into account the patient's FEV1 values (mild: >80%, moderate: 70–80%, or severe: <70% predicted), the number of asthma attacks in the past year (2, 3–6, or >6), the number of hospital admissions for respiratory problems in the past year (0, 1–2, or >2), and whether inhaled or oral corticosteroids were taken in the past year. Each criterion was scored as 1, 2, or 3 based on increasing severity with the exception of corticosteroid use, which was scored as either 1 or 2 (Table 1). Scores for all four criteria were combined to produce a severity score ranging from 4 to 11, with severity levels being mild (score 4 or 5), moderate (6), or severe (> or equal to 7). Severe patients (whether asthma was well controlled or not) were all excluded in this study.

Asthma severity scoring system.

| Variables | Score levels | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| FEV1 (%predicted) | >80 | 70–80 | <70 |

| Asthma attacks in the preceding year | 2 | 3–6 | >6 |

| Hospitalisations in the preceding year | 0 | 1–2 | >2 |

| Inhaled or oral corticosteroids taken in the preceding year | Inhaled corticosteroids | Oral corticosteroids | – |

Each criterion was scored as 1, 2, or 3 with the exception of corticosteroid use, with a cumulative asthma severity score ranging from 4 t o11. Severity levels were defined as mild (4–5), moderate (6), or severe (>7). FEV1, forced expiratory volume in one second.

All patients were treated by standardised SCIT with Alutard Dp vaccine. The treatment regime was set up according to the manufacturer's product insert (Table 2), and no cluster schedule administered to any patient. During the initial phase of SCIT, weekly injections were administered to reach an optimal dose. Subsequently, the patient followed maintenance injections every six weeks for three to five years. The maintenance dose was usually predefined by the manufacturer. Before each injection, patients had to have: 1) physical examination, 2) peak expiratory flow (PEF) test (only patients whose PEF was >80% of the predicted value were allowed to take the injection), and 3) assessment of local and SRs after a previous injection for dose adjustment. The dose was reduced in the case of SRs, unpleasant appreciable delayed local reactions, and exceeding the intervals between two series of injections. Doses were repeated if the diameter of the immediate local reaction was >5cm. Patients were observed by nurses and physicians in the clinic for at least 30min after each injection. Patients presenting with SRs were observed and rescue treatments were instituted by physicians. The SRs were classified based on symptoms and the patients’ responses to rescue treatments. If the SRs occurred after the patients had left the clinic, the physicians and patients would follow-up by telephone to ensure optimal treatments.

Treatment schedule of standardized immunotherapy.

| Time of injection | Vial | Volume (mL) | Concentration (SQ-U/mL) | Injection dose (SQ-U) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Build-up phase | ||||

| Week 1 | 1 | 0.2 | 100 | 20 |

| Week 2 | 1 | 0.4 | 100 | 40 |

| Week 3 | 1 | 0.8 | 100 | 80 |

| Week 4 | 2 | 0.2 | 1000 | 200 |

| Week 5 | 2 | 0.4 | 1000 | 400 |

| Week 6 | 2 | 0.8 | 1000 | 800 |

| Week 7 | 3 | 0.2 | 10,000 | 2000 |

| Week 8 | 3 | 0.4 | 10,000 | 4000 |

| Week 9 | 3 | 0.8 | 10,000 | 8000 |

| Week 10 | 4 | 0.1 | 100,000 | 10,000 |

| Week 11 | 4 | 0.2 | 100,000 | 20,000 |

| Week 12 | 4 | 0.4 | 100,000 | 40,000 |

| Week 13 | 4 | 0.6 | 100,000 | 60,000 |

| Week 14 | 4 | 0.8 | 100,000 | 80,000 |

| Week 15 | 4 | 1.0 | 100,000 | 100,000 |

| Maintenance phase | ||||

| Week 17 | 4 | 1.0 | 100,000 | 100,000 |

| Week 21 | 4 | 1.0 | 100,000 | 100,000 |

| Week 33 | 4 | 1.0 | 100,000 | 100,000 |

| Every 6 wk | 4 | 1.0 | 100,000 | 100,000 |

SQ: standardised quality.

A systemic reaction (SR) is defined as an adverse reaction involving organ-specific systems distant from the injection site. The severity of SRs is classified into 5 grades according to the World Allergy Organization (WAO) SCIT SR grading system.13 A reaction from a single organ system, such as cutaneous, conjunctival, or upper respiratory, but not asthma, gastrointestinal, or cardio-vascular is classified as grade 1. Symptoms/signs from more than one organ system, asthma (less than 40% PEF or FEV1 drop, responding to an inhaled bronchodilator), or gastrointestinal symptoms/signs are classified as grades 2; either asthma (more than 40% PEF or FEV1 drop, not responding to an inhaled bronchodilator) or laryngeal/uvula/tongue oedema with or without stridor as grade 3. Respiratory failure or hypotension, with or without loss of consciousness, was defined as grade 4, and death as grade 5. As for the time of the appearance of SRs after the administration of SCIT, SRs was classified as “early” (≤30min after SCIT) or “late” (>30min after SCIT) according to the classification of the EAACI guidelines.14 Data were collected from January 2011 to December 2016.

The study was approved by local ethics committee and notified to the relevant regulatory bodies. Each participator or his/her statutory guardian signed the informed consent of the immunotherapy.

Data were analysed with SPSS statistical software, version 20.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). Descriptive parameters, such as means and standard deviations for normally distributed continuous data, median percentiles for non-normally distributed continuous data, and frequencies and percentages for categorical data, were calculated. Pearson's χ2 tests were used to evaluate the association between SRs and categorical measures. Odds ratios (ORs) were calculated between groups, with 95% confidence intervals generated. A value of p<0.05 was considered as significant statistically.

ResultsIn total, 429 patients (295 males, 68.76%; 134 females, 31.23%), were included in this study. The mean age and median ages of patients were 9.37±0.17 and 9 respectively, ranging from 5 to 17 years, and there were 265 children (5–11 years) and 164 adolescents (12–17 years) (Table 3). All patients had a positive skin prick test for dust mites. Among the patients, 326 (75.99%) were monosensitised to dust mites, and 103 (24.01%) were multisensitised. A total number of 12,655 SCIT injections were administered. All patients completed the initial phase of SCIT. 223 patients (51.9%) completed the immunotherapy (the mean and median duration of SCIT were 167.54 and 171 weeks, respectively) and the other patients were still in the maintenance treatment when we analysed the data. From the beginning of the maintenance phase to the end of observations, 1.4% (6/429) patients withdrew. Two patients dropped out because of poor response to therapy after one year of treatment, four other patients because of migration to another city. No one stopped treatment because of complications (systemic reactions, local reactions, worsening of allergy symptoms).

Basic information of patients.

| Children (aged 5–11) | Adolescents (aged 12–17) | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 265 | 164 | 429 |

| Age (mean, range) | 7.02 (5–11) | 14.25 (12–17) | 9.37±0.17 |

| Male % (n) | 69.81% (185) | 67.07% (110) | 68.76% (295) |

| Monosensitised to dust mites % (n) | 75.47% (200) | 76.83% (126) | 75.99% (326) |

| Polysensitised % (n) | 24.53% (65) | 23.17% (38) | 24.01% (103) |

| Concomitant AD % (n) | 50.94% (135) | 28.05% (46) | 42.19% (181) |

| Concomitant AR % (n) | 53.58% (142) | 61.58% (101) | 56.64% (243) |

| Family history of atopy % (n) | 66.42% (176) | 74.39% (122) | 69.46% (298) |

| Food allergy % (n) | 14.72% (39) | 16.46% (27) | 15.38% (66) |

| Drug allergy % (n) | 21.51% (57) | 19.51% (32) | 20.74% (89) |

| Severity of asthma | |||

| Mild % (n) | 63.77% (169) | 63.41% (104) | 63.64% (273) |

| Moderate % (n) | 36.23% (96) | 36.58% (60) | 36.36% (156) |

AD: atopic dermatitis. AR: allergic rhinitis.

A total of 328 SRs were recorded in 67 patients for a rate of 2.59% per injection and 15.62% per patient. Forty-six patients experienced two SRs or more. There was a higher prevalence of SRs in children than adolescents (p<0.01), The rates of SRs were slightly higher in build-up phase than maintenance phase. A total of 142 SRs in children and 40 SRs in adolescents occurred during the build-up phase of immunotherapy (Table 4).

Prevalence of SRs in children and adolescents.

| Phase | Percentage of injection with SRs | p value | Percentage of patients with SRs | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Children % (n/N) | Adolescents % (n/N) | Children % (n/N) | Adolescents % (n/N) | |||

| Build-up | 3.83 (142/3706) | 1.678 (40/2385) | <0.01 | 11.7 (31/265) | 7.32 (12/164) | <0.01 |

| Maintenance | 2.79 (115/4123) | 1.27% (31/2441) | <0.01 | 6.79 (18/265) | 3.66 (6/164) | <0.01 |

| Total | 3.28 (257/7829) | 1.47 (71/4826) | <0.01 | 18.49 (49/265) | 10.98 (18/164) | <0.01 |

N: total number of patients who had entered the treatment phase. SR: systemic reaction.

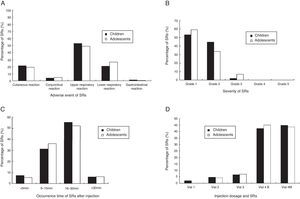

The prevalence of adverse events of SRs was shown in Fig. 1A. A total of 51.2% SRs were associated with reaction in the upper respiratory tract (sneezing, rhinorrhoea, nasal pruritus and/or nasal congestion, itchy throat, cough originating in the upper airway with normal chest sounds). The remaining events (shortness of breath, cough, and wheezing, declines in PEF or FEV1, urticaria, conjunctival pruritus, abdominal cramps) occurred at a lower frequency.

According to the WAO 2010 SCIT SR grading system, most SRs were classified as grade 1 (54.57%, total) and grade 2 (42.37%, total) in this study. Furthermore, the total of 3.05% SRs were grade 3 and no grades 4 or grade 5 SRs occurred in patients (Fig. 1B). To directly assess the relationship between SRs and asthma severity, we compared SRs prevalence between mild and moderate asthma. There was a higher prevalence of SRs in children and adolescents with moderate asthma than mild (p<0.01) (shown in Table 5).

Prevalence of SRs between mild and moderate asthma.

| Severity of asthma | Percentage of injection with SRs | p value | Percentage of patients with SRs | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mild % (n/N) | Moderate % (n/N) | Mild % (n/N) | Moderate % (n/N) | |||

| Children | 2.64 (132/4991) | 4.4 (125/2838) | <0.01 | 14.79 (25/169) | 25 (24/96) | <0.01 |

| Adolescents | 1.68 (40/2385) | 1.27 (31/2441) | <0.01 | 9.62 (10/104) | 13.33 (8/60) | <0.01 |

| Total | 2.32% (172/7376) | 2.96% (156/5269) | <0.01 | 18.49 (49/265) | 10.98 (18/164) | <0.01 |

N: total number of patients who had entered the treatment phase. SR: systemic reaction.

Fig. 1C shows the time of occurrence of SRs after injection. The vast majority (93.81%) of the SRs came up within 30min of the injection, with the earliest onset of 5min. Delayed reactions appeared in 6.2% SRs. There was no significant difference in the time of occurrence between children and adolescents (p>0.05). The SRs occurring at different dose were shown in Fig. 1D. Most of the SRs occurred during injection of No. 4 vial (100,000 SQ-U/mL). In adolescents, SRs did not occur with No. 1 vial (100 SQ-U/mL). All patients with SRs had satisfactory results to treatment with medications, such as oral H1 antihistamines, inhaled β2 agonists, and intramuscular epinephrine (Table 6). The signs of treatment with intramuscular epinephrine are as follows: sudden skin mucosal symptoms (e.g. generalised hives, swollen lips-tongue-uvula), sudden respiratory symptoms (e.g. shortness of breath, hypoxaemia), sudden reduced BP or symptom of end-organ dysfunction (e.g. hypotonia (collapse), incontinence), sudden gastrointestinal symptom (e.g. crampy abdominal pain). There was no need for hospitalisation. According to the extracts production directions, injection dose in patients who experienced an SR were downgraded one step or reduced 0.2mL at the next injection visit, and then gradually increased to the maintenance dose.

Multivariate logistic regression demonstrated that children and moderate asthma were risk factors associated with SRs for patients who received SCIT (Table 7).

Risk factors for SRs to SCIT analysed by logistic regression.

| OR | Lower | Upper | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (children) | 4.71 | 3.446 | 6.473 | 0.001 |

| sex (male) | 1.044 | 0.588 | 1.856 | 0.882 |

| Family history of atopy | 1.010 | 0.564 | 1.808 | 0.973 |

| Concomitant AD | 0.934 | 0.531 | 1.643 | 0.813 |

| Concomitant AR | 1.298 | 0.758 | 2.223 | 0.341 |

| Severity of asthma (moderate) | 1.58 | 1.28 | 1.96 | 0.001 |

SR: systemic reaction.

SCIT is the practice of administering gradually increasing quantities of an allergen product to an allergic subject, reaching a dose that is effective in ameliorating the symptoms associated with the subsequent exposure to the causative allergen.13 SCIT can induce immunological tolerance and may prevent the progression of allergic disease such as allergic asthma. Adverse SCIT reactions are generally classified into two categories: local reactions, which can manifest as pruritus, erythema and swelling at the injection site; and SRs. SRs can range in severity from mild to very severe life-threatening anaphylaxis. SRs have attracted great attention in the practice of SCIT because of possible anaphylaxis and severe consequences.15 There are several surveys on the safety of SCIT, providing results that vary according to the recording system, the country and the schedule utilised. This study aimed to investigate the safety profile of SRs to standardise dust mite immunotherapy in Hangzhou, east China's Zhejiang province.

Altogether, our results showed that SCIT was well tolerated in patients with asthma over the years of treatment, since SRs occurred in 15.62% of patients and 2.59% of injections. Previous studies indicate that the frequency of SRs during allergen immunotherapy varies from less than 2% to 15.9% of patients receiving SCIT.16,17 The reason was that authors applied various vaccines (allergoids) and had different observation times. In this study, children and adolescents had the same treatment schedule and dose that was based on the product fact sheets. Children had more SRs than adolescents during SCIT irrespective of the percentage of injection (3.28% in children versus 1.47% in adolescents) or patient number (18.49% in children versus 10.98% in adolescents). In keeping with our study, previous researches18,19 indicate a higher risk in children than adolescents or adults, whereas one study shown no relationship between SRs and age.20 Our rates of SRs are slightly higher than other studies. A possible explanation is that our study included more young children who might be greatly sensitised and vulnerable to allergies with less capacity of tolerance to allergen extracts.18 This difference may also reflect a higher proportion of children in subjects undergoing allergen-specific SCIT in Hangzhou, east China.

In our study, we found severity of asthma to be a risk factor. Both no asthmatic symptoms and PEF and/or FEV1>80% of the predicted value were taken as an indication for injection. In spite of this, patients with moderate asthma had a much higher rate of SRs than patients with mild asthma. Previous studies described that patients with severe or uncontrolled asthma are at increased risk for SRs to SCIT.21,22 One study showed that the pulmonary function of asthmatics was predictive of SRs during SCIT with HDM,23 and there was a significantly higher frequency of asthma symptoms in patients with previous asthma compared with patients with no asthma in their history. Another study found that asthma patients less frequently reached the maintenance dose and more frequently had grade 2–4 reactions compared with grade 1 reactions.24 It was suggested that the severity of asthma should been considered a critical risk factor for the development of SRs during SCIT. It is necessary to observe and follow up patients with moderate asthma more closely after SCIT injections. We also propose that, before each SCIT administration, an assessment of asthma control (including Cardiopulmonary auscultation, and Asthma control questionnaires) and pulmonary function testing should be performed before each SCIT injection in patients with asthma.

As shown in this study, most of the SRs occurred during injection of No.4 vial (at the highest concentration). The rates of SRs were slightly higher in build-up phase than maintenance phase. The occurrence of SRs is likely to be dependent on the dose of allergen extracts. This highlights the importance of keeping patients carefully controlled during the whole treatment, and not just in the build-up phase. SRs may occur at any time in the course of SCIT, even when the patient has been receiving the same maintenance dose of extract for years, and even when SCIT is appropriately administered. It is also suggested that we should be alert to the greater possibility of SRs in patients during injection at the highest concentration.

The time of onset of SRs is of great importance, because it defines the appropriate waiting period in the office following the injection.10 Consistent with the data reported by many studies, most (93.81%) of the SRs in our study occurred within 30min after the injection. Almost all of the late side-effects were handled by the patients. Several previous studies also reported that up to 50% of the SRs occurred after 30min.8,15,25,26 The reason for the discrepancy between the reports is not clear, the difference between allergens could be a part of the explanation. Winther et al.8 reported that increasing the observation period to one hour did not seem to change the proportion of side-effects occurring at the clinic significantly. Thus, in addition to staying and observation for 30min after the injection recommended by guidelines, it is essential to instruct patients how to deal with delayed-onset SRs,27 and high-risk subjects (e.g., those with moderate asthma or repeated SRs) should be observed for a longer period of time. In addition, although severe late-onset SRs appear to be relatively rare events, they do occur, and adequate treatment of emergency conditions is necessary.

With increasing vigilance against severe SRs during SCIT, fatal SRs occurrence are declining in recent years.28,29 All SRs in this study range from grade 1 to grade 3, and were completely resolved with antihistamines and/or inhaled β2-agonists or adrenaline administration, without occurrence of fatal reactions. This is in accordance with other studies.30,31 Recently, a cross-sectional, retrospective trial involving 3723 patients reported that all SRs were of grade 1 and grade 2.30 The rather good outcome of the SRs was due to our following the guidelines and strictly assessing the patient's conditions before each treatment, such as asthma control tests and PEF/FEV1 levels.

As can be seen from the above findings, moderate asthma, being young, and high concentration of allergen extracts may be associated with SRs during SCIT. Furthermore, multivariate logistic regression analysis showed children and moderate asthma are independent risk factors for SRs. There was no difference in prevalence of SRs between subjects who were concomitant with atopic dermatitis (AD) or allergic rhinitis (AR) and those who were not. AD is the most common chronic dermatitis in children, and the prevalence decreases with age,32 in accordance with our result. Similarly, we did not find allergic monosensition/polysensitisation or allergies to food to be a risk factor. The major limitations in this report are its retrospective nature and single-centre study rather than a placebo-controlled study. So our results may not accurately represent the general Eastern Chinese population.

In summary, our study demonstrated that SCIT was a safe treatment with mild and moderate (grade 1 and grade 2) SRs, in which no fatality was observed due to the SRs in children and adolescents in Hangzhou, east China. Considering the results presented in this survey, we conclude that the age and severity of asthma are important risk factors in possibly inducing SRs in children with asthma, who receive SCIT. Further prospective studies on side-effects with SCIT are necessary to confirm these associations.

Ethical disclosuresConfidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.

Protection of human subjects and animals in researchThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

This study was partially supported by grants from the Education Department of Zhejiang Province, China (No. Y201534178).