Atopic dermatitis (AD) has been associated with impairment of sleep. The aim of this study was to evaluate sleep disorders in AD Latin-American children (4–10 years) from nine countries, and in normal controls (C).

MethodsParents from 454 C and 340 AD children from referral clinics answered the Children Sleep Habits Questionnaire (CSHQ), a one-week retrospective 33 questions survey under seven items (bedtime resistance, sleep duration, sleep anxiety, night awakening, parasomnias, sleep-disordered breathing and daytime sleepiness). Total CSHQ score and items were analysed in both C and AD groups. Spearman's correlation coefficient between SCORAD (Scoring atopic dermatitis), all subscales and total CSHQ were also obtained.

ResultsC and AD groups were similar regarding age, however, significantly higher values for total CSHQ (62.2±16.1 vs 53.3±12.7, respectively) and items were observed among AD children in comparison to C, and they were higher among those with moderate (54.8%) or severe (4.3%) AD. Except for sleep duration (r=−0.02, p=0.698), there was a significant Spearman's correlation index for bedtime resistance (0.24, p<0.0001), sleep anxiety (0.29, p<0.0001), night awakening (0.36, p<0.0001), parasomnias (0.54, p<0.0001), sleep-disordered breathing (0.42, p<0.0001), daytime sleepiness (0.26, p<0.0001) and total CSHQ (0.46, p<0.0001). AD patients had significantly higher elevated body mass index.

ConclusionLatin-American children with AD have sleep disorders despite treatment, and those with moderate to severe forms had marked changes in CSHQ.

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a complex chronic inflammatory skin disease, caused by the interaction of multiple genetic and environmental factors. Although beginning early in life, 90% of cases are manifested before the age of five.1

Since it is a chronic and recurrent disease, its control is a real challenge because AD interferes in social relationships, psychological status and daily activities of patients.2,3

Observational studies have identified sleep disorders in 47–60% of children with AD4 reaching 83% during exacerbations and can even persist in AD remission.5 The frequency and duration of sleep disorders overnight provide a simple measure of the effect that AD has on patient's quality of life.2,3

Difficulty falling asleep, night-time awakenings, and difficulty waking up in the morning, have been observed in more than half of patients with AD.6 In addition, AD impairs the daily functioning of patients and their parents, it imposes increased anxiety and/or depression of parents. Furthermore, AD induces an overload with patient care, favouring the development of conflicts between parents and healthy siblings by affecting the family structure3,7 and the emotional and social well-being of all family members.8

The recognition of the emotional burden AD and sleep disorders may impose on the home, school and work environment, as well as the emotional status of parents, must always be considered in clinical evaluation of patients,6 since these factors contribute to the severity of this disease.2,3 It is also important to know whether the child's sleep needs are being met.9

Written questionnaires (WQ), easy to administrate and highly cost-effective, have been increasingly used to assess children's sleep behaviour, although they only accomplish subjective and retrospective assessments.

The Children's Sleep Habits Questionnaire (CSHQ) is an example of such an epidemiologic tool. Originally available in English,10 it was translated into and validated for Portuguese11 and Spanish as well,12 and proved to be a useful tool in the evaluation of sleep-related disorders in children.

Although AD is a disease of high prevalence that can interfere with the quality of life of patients, few studies have evaluated the relationship between AD and sleep disorders in Latin American children attending specialty clinics.

Identifying sleep disorders in children with AD from different populations and cultures will allow to determine the possible interactions of factors in their environment that make them more vulnerable to increased morbidity of AD.13

Patients and methodsA multicentre cross-sectional study enrolled children, 4–10 years old from nine countries in Latin America (Argentina [AD=30; Control (C)=51]; Brazil [AD=49; C=62]; Colombia [AD=31; C=50]; Cuba [AD=48; C=50]; Dominican Republic [AD=32; C=50]; Honduras [AD=30; C=50]; Mexico [AD=35; C=65]; Paraguay [AD=45; C=39]; and Uruguay [AD=40; C=37]) who attended allergy clinics. The study groups were composed of children with AD14 and a matched control group (age and socioeconomic status) of non-allergic healthy individuals that were evaluated from March to April 2015. Non-allergic individuals apparently healthy were followed in each paediatric clinic for routine visits and immunisations. None of them had any chronic disease, malformation or genetic disease.

Each study site was requested to include at least 30 patients and 30 controls, matched for age, gender and socioeconomic status. Children were admitted when they attended for routine visit in each participating centre, from March to April 2015, until the number of settled cases was reached. On admission, subjects were classified according to the presence or absence of AD. All parents and/or guardians signed informed consent forms and answered the CSHQ, a retrospective and recall questionnaire about sleep-related symptoms the week prior to entering the study. Brazil used the Portuguese validated CSHQ version11 and other Latin-American countries used the Spanish validated version.12

The CHSQ consists of 33 questions divided into items, namely: resistance at bedtime (goes to bed at same time; falls asleep in own bed; falls asleep in other's bed; needs parent in the room to sleep; struggles at bedtime; afraid of sleeping alone – range: 6–18 points); sleep delay (range: 1–3 points); sleep duration (sleeps too little; sleeps the right time; sleeps same amount each day – range: 3–9 points); (c) sleep anxiety (needs parent in the room to sleep; afraid of sleeping in the dark; afraid of sleeping alone; trouble sleeping away – range: 4–12 points); night walking (moves to other bed in the night; awakens once during night; awakens more than once – range: 3–9 points); parasomnias (wets the bed at night; talks during sleep; restless and moves a lot; sleepwalks; grinds teeth during sleep; wakes up screaming, sweating; alarmed by nightmare – range: 7–21 points); sleep-disordered breathing (snores loudly; apnoea; snorts and gaps – range: 3–9 points) and daytime sleepiness (wakes by himself; wakes up in negative mood; others wake child; hard time getting out of bed; takes long time to be alert; seems tired; watching TV; riding in car – range: 8–24 points). The score was obtained by summing the points ascribed to the related questions and the total score (range: 35–105 points) was achieved by the sum of the scores of the seven items.10

The severity of AD was assessed by a trained allergist applying the Objective Scoring Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD; maximum 83 points [plus an additional 10 bonus points]) index and classified as having mild AD (from 0 to 14), moderate AD (from 15 to 40), or severe AD (higher than 41).15

Children's nutritional status by Body Mass Index (BMI, weight/height2, Anthro OMS.22 Plus®), was compared to World Health Organisation reference and expressed in BMI Z score (zBMI).16

CSHQ total scores and the secondary scores were compared between controls and patients with AD by non-parametric tests (Mann–Whitney). The relationship between impaired sleep and severity of AD and of impaired sleep and BMI according to AD severity were analysed by the Spearman correlation coefficient. In all tests the rejection level for the null hypothesis was set at 5%. All centres had the protocol approved by their respective institutional review board in accordance with the World Medical Association and the Helsinki Declaration, and parents and/or guardians signed the informed consent.

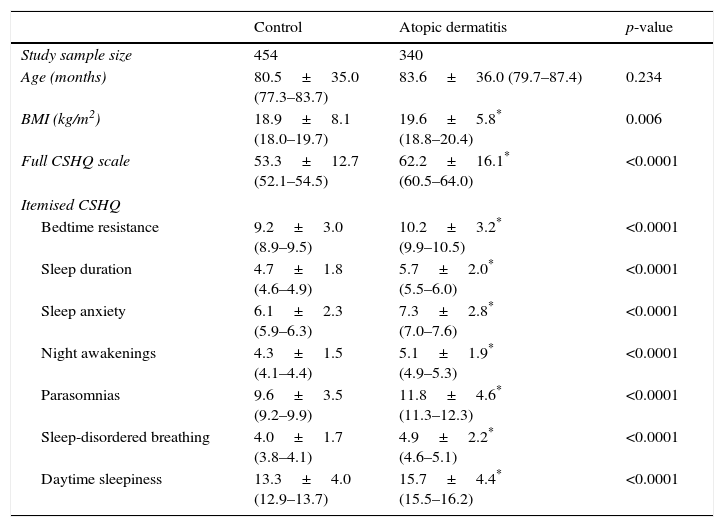

ResultsAD was associated with asthma and/or allergic rhinitis in 20.1% (75/340). Control and AD groups were similar regarding age. However, BMI was higher among AD children, as well as CSHQ total score and its secondary scores (Table 1).

Comparative analysis of Latin-American children (controls and with atopic dermatitis) according to age, body mass index (BMI), total scale score and subscale scores of the Children's Sleep Habits Questionnaire (CSHQ).

| Control | Atopic dermatitis | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Study sample size | 454 | 340 | |

| Age (months) | 80.5±35.0 (77.3–83.7) | 83.6±36.0 (79.7–87.4) | 0.234 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 18.9±8.1 (18.0–19.7) | 19.6±5.8* (18.8–20.4) | 0.006 |

| Full CSHQ scale | 53.3±12.7 (52.1–54.5) | 62.2±16.1* (60.5–64.0) | <0.0001 |

| Itemised CSHQ | |||

| Bedtime resistance | 9.2±3.0 (8.9–9.5) | 10.2±3.2* (9.9–10.5) | <0.0001 |

| Sleep duration | 4.7±1.8 (4.6–4.9) | 5.7±2.0* (5.5–6.0) | <0.0001 |

| Sleep anxiety | 6.1±2.3 (5.9–6.3) | 7.3±2.8* (7.0–7.6) | <0.0001 |

| Night awakenings | 4.3±1.5 (4.1–4.4) | 5.1±1.9* (4.9–5.3) | <0.0001 |

| Parasomnias | 9.6±3.5 (9.2–9.9) | 11.8±4.6* (11.3–12.3) | <0.0001 |

| Sleep-disordered breathing | 4.0±1.7 (3.8–4.1) | 4.9±2.2* (4.6–5.1) | <0.0001 |

| Daytime sleepiness | 13.3±4.0 (12.9–13.7) | 15.7±4.4* (15.5–16.2) | <0.0001 |

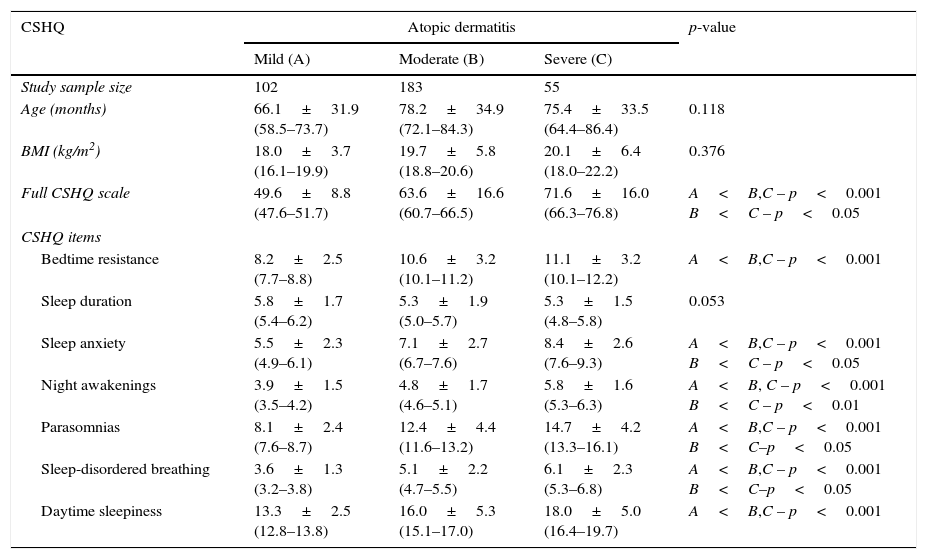

There were no differences in age and BMI according to the severity of AD (Table 2). Patients with moderate AD (53.8%) and those with severe AD (16.2%) showed significant changes in total CSHQ score and secondary scores in comparison with patients with mild AD (29.9%) except for sleep duration (Table 2).

Comparative analysis of Latin-American children with atopic dermatitis according to severity of disease based on Scoring Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD) index (mild: 0–20; moderate: 21–40; severe: more than 41) – total scale score and item scores of the Children's Sleep Habits Questionnaire (CSHQ).

| CSHQ | Atopic dermatitis | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mild (A) | Moderate (B) | Severe (C) | ||

| Study sample size | 102 | 183 | 55 | |

| Age (months) | 66.1±31.9 (58.5–73.7) | 78.2±34.9 (72.1–84.3) | 75.4±33.5 (64.4–86.4) | 0.118 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 18.0±3.7 (16.1–19.9) | 19.7±5.8 (18.8–20.6) | 20.1±6.4 (18.0–22.2) | 0.376 |

| Full CSHQ scale | 49.6±8.8 (47.6–51.7) | 63.6±16.6 (60.7–66.5) | 71.6±16.0 (66.3–76.8) | A<B,C – p<0.001 B<C – p<0.05 |

| CSHQ items | ||||

| Bedtime resistance | 8.2±2.5 (7.7–8.8) | 10.6±3.2 (10.1–11.2) | 11.1±3.2 (10.1–12.2) | A<B,C – p<0.001 |

| Sleep duration | 5.8±1.7 (5.4–6.2) | 5.3±1.9 (5.0–5.7) | 5.3±1.5 (4.8–5.8) | 0.053 |

| Sleep anxiety | 5.5±2.3 (4.9–6.1) | 7.1±2.7 (6.7–7.6) | 8.4±2.6 (7.6–9.3) | A<B,C – p<0.001 B<C – p<0.05 |

| Night awakenings | 3.9±1.5 (3.5–4.2) | 4.8±1.7 (4.6–5.1) | 5.8±1.6 (5.3–6.3) | A<B, C – p<0.001 B<C – p<0.01 |

| Parasomnias | 8.1±2.4 (7.6–8.7) | 12.4±4.4 (11.6–13.2) | 14.7±4.2 (13.3–16.1) | A<B,C – p<0.001 B<C–p<0.05 |

| Sleep-disordered breathing | 3.6±1.3 (3.2–3.8) | 5.1±2.2 (4.7–5.5) | 6.1±2.3 (5.3–6.8) | A<B,C – p<0.001 B<C–p<0.05 |

| Daytime sleepiness | 13.3±2.5 (12.8–13.8) | 16.0±5.3 (15.1–17.0) | 18.0±5.0 (16.4–19.7) | A<B,C – p<0.001 |

Mann–Whitney.

There was a significant correlation between the SCORAD indexes in patients with AD and CSHQ total score (r=0.46, p<0.0001) and the secondary item scores: bedtime resistance (r=0.24, p<0.0001), sleep anxiety (r=0.29, p<0.0001), night awakenings (r=0.36, p<0.0001) parasomnias (r=0.54, p<0.0001), sleep-disordered breathing (r=0.42, p<0.0001), daytime sleepiness (r=0.26, p<0.0001). Nevertheless, the sleep duration showed no significant correlation (r=−0.02, p=0.698). The relationship between BMI and CHSQ total score according to the severity of AD showed significant correlation only for moderate AD (r=12.44; p<0.0001) (Table 2).

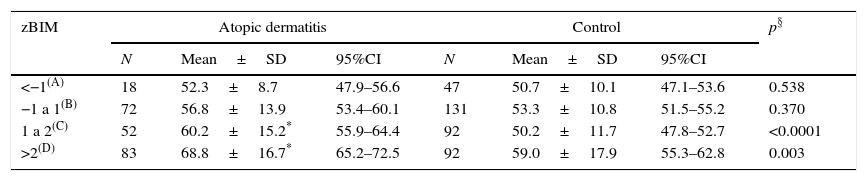

CSHQ total score was significantly higher for those with more than 2 zBMI in both AD and control groups. Between groups analysis showed CHSQ total score values significantly higher among those with AD and zBMI higher than 1 in comparison to controls (Table 3).

Comparative analysis of total scale score of the Children's Sleep Habits Questionnaire (CSHQ; mean±standard deviation) of Latin-American children with atopic dermatitis and controls according to the interval of body mass index expressed in Z score (zBMI).

| zBIM | Atopic dermatitis | Control | p§ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean±SD | 95%CI | N | Mean±SD | 95%CI | ||

| <−1(A) | 18 | 52.3±8.7 | 47.9–56.6 | 47 | 50.7±10.1 | 47.1–53.6 | 0.538 |

| −1 a 1(B) | 72 | 56.8±13.9 | 53.4–60.1 | 131 | 53.3±10.8 | 51.5–55.2 | 0.370 |

| 1 a 2(C) | 52 | 60.2±15.2* | 55.9–64.4 | 92 | 50.2±11.7 | 47.8–52.7 | <0.0001 |

| >2(D) | 83 | 68.8±16.7* | 65.2–72.5 | 92 | 59.0±17.9 | 55.3–62.8 | 0.003 |

Kruskall–Wallis – Atopic dermatitis: p<0.001 – Dunn: A, B, C<D.

Control: p<0.002 – Dunn: C<B, D

§ Mann–Whitney.

* Significantly higher.

95%CI – 95% confidence interval.

Sleep problems have negative consequences for all children but also a potential impact on the course and severity of disease.17 In patients with AD, itching and burning sensation of skin can affect patient's quality of sleep, as well as problems arising from treatment regimens for its control.18

Age and socioeconomic status have been identified as capable of interfering with sleep in children. The strength of this study was the inclusion of a control group, matched by age, gender and socioeconomic status to observe that the sleep disturbances resulted from the AD itself. Children with AD may be at higher risk for adverse outcomes of sleep caused by independent contribution or potential interaction of factors related to genetic predisposition, disease severity, psychological, social, cultural factors, beliefs and values that affect decisions about routine sleep behaviour in the family.17 This has not been observed in our study, as there were no differences in sleep-related disorders among the various AD subgroups studied.

On the other hand, socioeconomic status is a risk factor for sleep-related disorders in children with AD.19 Although the socioeconomic status has not been stratified in this study, it can be stressed that the majority of AD patients had free access to primary health care governmental services.

Another important factor for the onset of sleep behaviour changes observed in patients with AD concerns the disease per se, i.e. severity and treatment regimen established. An unexpected finding was the tendency to overweight in AD patients (Table 1).

Studies have documented that the more severe AD the greater the chances of some impairment of quality of life and sleep-related disorders.8,20 To determine this possible interaction, all patients in the current study were assessed by the SCORAD index. High SCORAD values were significantly associated with low efficiency and sleep fragmentation. Scores greater than 48.7 were highly sensitive, specific and considered good predictors of impaired sleep efficiency.21 Patients with AD have experienced longer duration of sleep than controls, suggesting sleep was not restful because daytime sleepiness was higher among children with AD (Table 1). On the other hand, stratifying patients according to severity of AD, although we have not detected significant difference in sleep duration, we did find that moderate and severe forms are accompanied by greater daytime sleepiness (Table 2). Would treatment regimen have anything to do with these findings? Although there is no consensus regarding the use of oral antihistamines H1 in the treatment of AD, nearly all patients have received such medication.22

It is believed that since first generation H1 antihistamines induce drowsiness, they would be the drug of choice for children with AD, particularly for control of pruritus. However, they have other undesirable side effects such as anticholinergic and sedative action on the central nervous system. These drugs administered at night might increase the latency to the onset of rapid eye movement (REM) sleep phase and reduce the duration of REM sleep. The lack of restful sleep may cause attention deficit, lower vigilance, memory deficit and a reduction in motor and sensory performance the next day.23,24

Asthma, especially uncontrolled, as well as allergic rhinitis have been associated with sleep disorders in comparison to normal controls. In a recent study we confirmed these findings evaluating Latin-American children with asthma and/or rhinitis with CSHQ.25 In this study, the association of asthma and/or allergic rhinitis was not able to interfere in the CHSQ total score (data not shown).

Sleep disorders have been related to both overweight and obesity. Patients with AD in the present study had BMI higher than control subjects (Table 1). Stratification by AD severity has shown no significant influence of this variable. However, distribution of patients according to zBMI sleep abnormalities was more severe among those with overweight and obesity (Table 3). This pattern has not been observed in the control group, suggesting that overweight carries the risk of sleep disorder.

The use of CSHQ allowed assessing complete background information on the various sleep disorders in this group of children.10 As expected, we observed higher values of CSHQ among children with AD compared to controls, and no differences among the various countries participating in the study. This difference occurred in all the items comprising the CSHQ except duration of sleep (Table 1).

During the validation of CSHQ either in Portuguese or in Spanish, it was found that 41 was the average total score above which sleep-related problems would be identified.11,12 Both controls and AD patients showed average total score higher than the cut-off point obtained during CHSQ validation (Table 1), which was also higher than the observed in other diseases.26,27 This difference in our study could be due to the low utilisation of CSHQ in evaluation of children with AD,28 greater number of patients, or that the cut-off of 41 observed in validations could be very conservative for the type of population we studied. Moreover, it is possible that other new local factors can act and interfere with the sleep of children a decade after the development of the original study when CSHQ was devised.10

Our study has some limitations: a cross-sectional design cannot determine the causality of this association. Sleep quality was assessed by a questionnaire completed by parents/caregivers. Polysomnography, the best objective method to evaluate sleep-related disorders could support our findings. Although these patients were evaluated by allergologists trained in the management of AD, an inter-observer variability using SCORAD should be considered. The use of such methods on a large scale has been limited by operational and economic constraints, particularly in a study conducted in different populations and countries.29

Nevertheless, we have demonstrated in this study that CSHQ is an easy handling and convenient tool, sensitive enough to discriminate different behavioural sleep problems in this risk group from different countries. One may argue the homogeneity of our sample, made up of children from different countries and cultures in Latin America, the control group minimised bias and allowed a closer assessment of the reality of children from each locality.

The impairment of quality of life caused by AD in childhood has been shown to be greater than or equal to other common diseases in children such as asthma and diabetes, emphasising the importance of AD as one of the major chronic diseases of childhood.26,27 The hidden costs involved in the management of AD, as sleep disorders, can significantly impact low-income families.

ConclusionsOur results highlight the possibility that the night-time symptoms of a child with AD reported by parents and/or caregivers may not be recognised by health care providers, for lack of knowledge and proper investigation.29–31 Thereby, research directed to these disorders must be incorporated into medical and nursing assessment32 in order to detect them early on and enable the introduction of appropriate practices aimed at reducing the impact of negative effects of daytime sleepiness. Fatigue, changes in behaviour and mood, cognitive and school functioning of these children stress the poor quality of life of patients and family members.

Ethical disclosuresConfidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects mentioned in the article. The author for correspondence is in possession of this document.

Protection of human subjects and animals in researchThe authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the responsible Clinical Research Ethics Committee and in accordance with those of the World Medical Association and the Helsinki Declaration.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.