Considering that no studies have been done on a comprehensive review of Serum sickness-like reactions patients (SSLRs) at a referral center in Iran so far, this study aimed to determine the clinical and laboratory characteristics of children with SSRL in Tehran Children’s Medical Center.

PatientsThe present study was a registry-based study in which the data of 94 SSLRs patients registered in a two-year period were investigated. Confirmation of fever, rash, urticaria, arthralgia / arthritis and history of antibiotic consumption up to three weeks before were the criteria for the diagnosis.

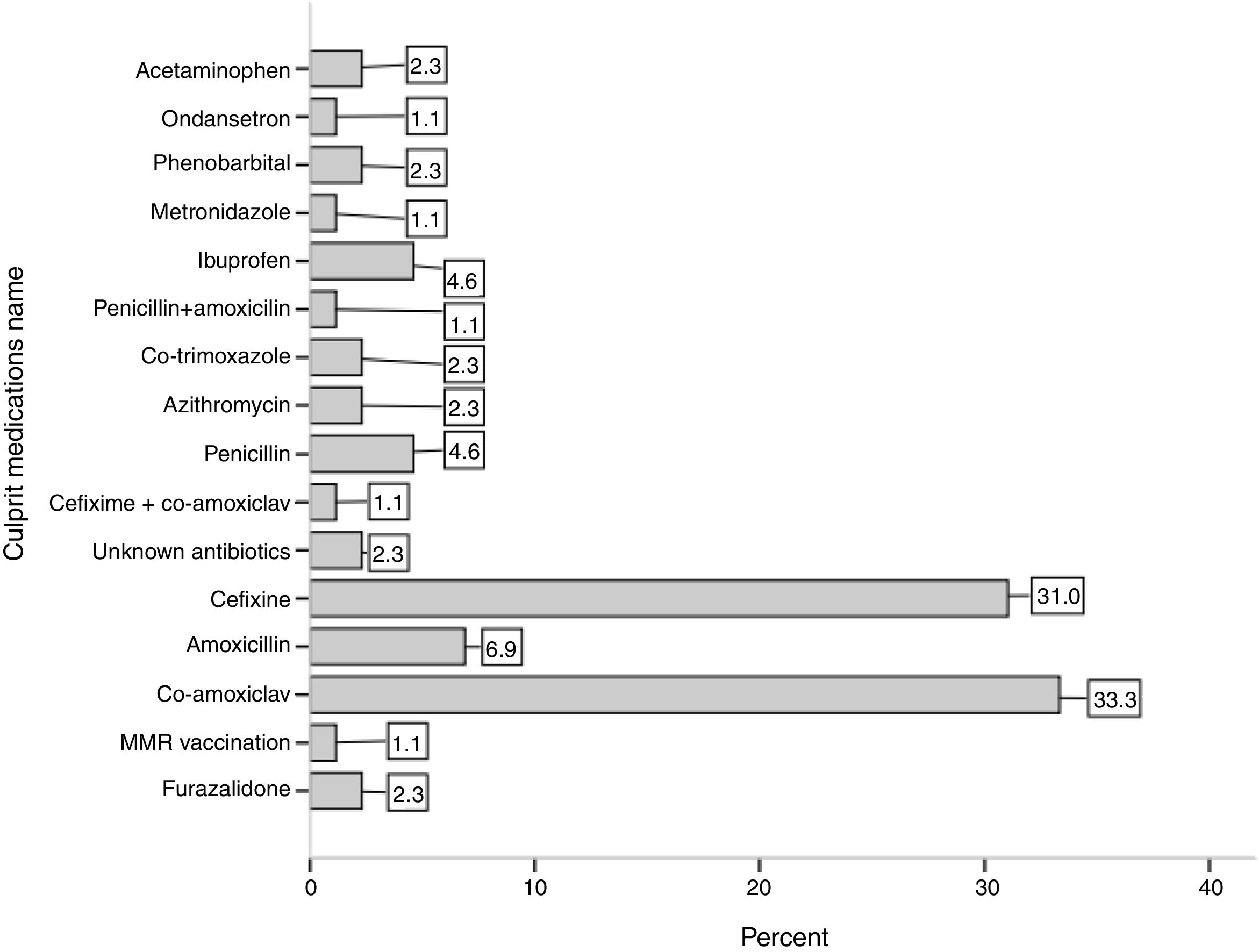

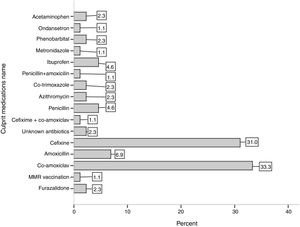

ResultsFifty-one (54 %) patients were male with mean age of 56 ± 30 months and there was no significant difference in the age of the two genders. The mean onset of symptoms before hospitalization were 3.8 ± 2.7 days (1–14 days); this mean was significantly higher in males than in females (4.6 ± 2.9 versus 2.9 ± 1.7 days, P-value = 0.003). Among antibiotics, Co-amoxiclav and Cefixime antibiotics had the most frequency by 31 % and 33 %, respectively as the most important incidence factor of SSLRs. The mean duration of consumption of culprit medications in the incidence of SSLRs was 5.6 ± 2.9 days with a range of 1–15 days.

ConclusionsThis study showed that among the antibiotics, Co-amoxiclav and Cefixime are more prevalent and a review of prescribing these two antibiotics for the treatment of the children’s infections is essential if this finding is confirmed by other Iranian scholars.

Serum sickness is a type III hypersensitivity reaction which is caused due to the accumulation of immune complexes, small vessel vasculitis and inflammation of tissues, and was first introduced by Schick and Pirquet.1 In the past, serum sickness was caused more by exposure to foreign antigenic agents like the heterologous serum, but today the types of antibiotics and especially Penicillins are the main causes of this disease, and for this reason, it is called serum sickness-like reactions (SSLR).2 Clinically and therapeutically, it is similar to serum sickness, and Fever, Rash, Lymphadenopathy, Arthralgia and Arthritis are the most important non-specific clinical manifestations of this disease3,4 that are usually manifested 7–10 days after prescribing or, depending on the patient’s sensitivity, in a shorter period of time.5,6 Therefore, the only way to diagnose this disease is to determine the type of substance used that has antigenic properties due to the non-specific symptoms and a relatively long period of time to incidence of symptoms. TNF-α inhibitor Infliximab,7,8 Cefaclor, and other Cephalosporin,9–11 inactivated influenza vaccine,12 and Clarithromycin13 are examples of treatments that have been reported in several studies as an incidence factor of SSLR. Although many studies have been conducted on SSLR in various parts of the world so far, many of these studies as a Case Report have reported the incidence of SSRL due to consuming a specific medication. Given the low prevalence of this syndrome compared with other pharmaceutical complications which albeit are clinically important, they are not the most reliable source for making important decisions in order to identify the most common symptoms and complications as well as the causes of this disease. Therefore, as no study has been conducted on a comprehensive review of SSRL patients at a reference center in Iran so far, this study was conducted with the aim of determining the clinical and laboratory characteristics of children with SSRL in Tehran Children’s Medical Center.

MethodsThe present study was a registry-based study in the Allergy and Clinical Immunology, Department of Children’s Medical Center, as a pediatric referral center with the data of 94 SSLR patients registered from January 2017 to the end of December 2018 investigated. Demographic, clinical, and laboratory information of all children who were hospitalized with a presumptive diagnosis of SSLRs entered in the SSLR registry after confirming the diagnosis by allergy specialists. Confirmation of fever, rash, urticaria, arthralgia/arthritis and history of antibiotic consumption up to three weeks before were the criteria for the diagnosis. Information required for analysis in this study included age, gender, duration of onset of symptoms before hospitalization, clinical symptoms, pharmacological agent, history of allergy in the patient and the family, the time interval between the consumption of antigenic substance and the onset of clinical symptoms and laboratory findings. Dispersion and central indicators, including the mean and standard deviation for the quantitative variables and percent and frequency for the classified variables were used to describe the results of this research. t-test was used to compare the mean of quantitative variables after confirming the normality of the data by Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. All tests were performed at the significance level of 5 % using SPSS version 18.

ResultsDuring the two-year period of investigation after applying the exclusion criteria, 94 children were registered with the diagnosis of SSLRs in the registry of Children’s Medical Center. Fifty-one (54 %) patients were male. The mean age of patients was 56 ± 30 months and there was no significant difference in the age of the two genders (P-Value = 0.523). The mean onset of symptoms before hospitalization had been 3.8 ± 2.7 days (1–14 days); with this mean being significantly higher in males than in females (4.6 ± 2.9 versus 2.9 ± 1.7 days, P-value = 0.003). The mean duration of hospitalization in patients was 2.5 ± 1.7 day (1–7 days), and there was no significant difference between the mean duration of hospitalization in males and females (P-Value = 0.665). Among antibiotics, Co-amoxiclav and Cefixime antibiotics had the largest frequency with 31 % and 33 %, respectively as the most important incidence factor of SSLRs. Fig. 1 shows other culprit medications in the incidence of SSLRs. The mean duration of consumption of the medications in the incidence of SSRL was 5.6 ± 2.9 days, with a range of 1–15 days.

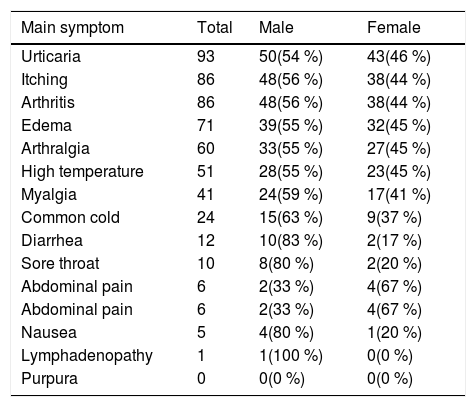

The mean duration of consumption of Co-amoxiclav and Cefixime were 5.9 ± 3 and 6.1 ± 2.7 days, respectively. Urticaria (98 %), itching (91.5 %) and arthritis (91.5 %) were the most common clinical symptoms of patients, and petechiae was not observed in any of the patients. Diarrhea (83 %), nausea (80 %) and sore throat (80 %) were the other most common symptoms in males, and abdominal pain (67 %), urticaria (46 %), high temperature (45 %), edema (45 %), arthralgia (45 %) were the other most common symptoms in females (Table 1).

Frequency of Clinical Symptoms in SSRL Patients by sex.

| Main symptom | Total | Male | Female |

|---|---|---|---|

| Urticaria | 93 | 50(54 %) | 43(46 %) |

| Itching | 86 | 48(56 %) | 38(44 %) |

| Arthritis | 86 | 48(56 %) | 38(44 %) |

| Edema | 71 | 39(55 %) | 32(45 %) |

| Arthralgia | 60 | 33(55 %) | 27(45 %) |

| High temperature | 51 | 28(55 %) | 23(45 %) |

| Myalgia | 41 | 24(59 %) | 17(41 %) |

| Common cold | 24 | 15(63 %) | 9(37 %) |

| Diarrhea | 12 | 10(83 %) | 2(17 %) |

| Sore throat | 10 | 8(80 %) | 2(20 %) |

| Abdominal pain | 6 | 2(33 %) | 4(67 %) |

| Abdominal pain | 6 | 2(33 %) | 4(67 %) |

| Nausea | 5 | 4(80 %) | 1(20 %) |

| Lymphadenopathy | 1 | 1(100 %) | 0(0 %) |

| Purpura | 0 | 0(0 %) | 0(0 %) |

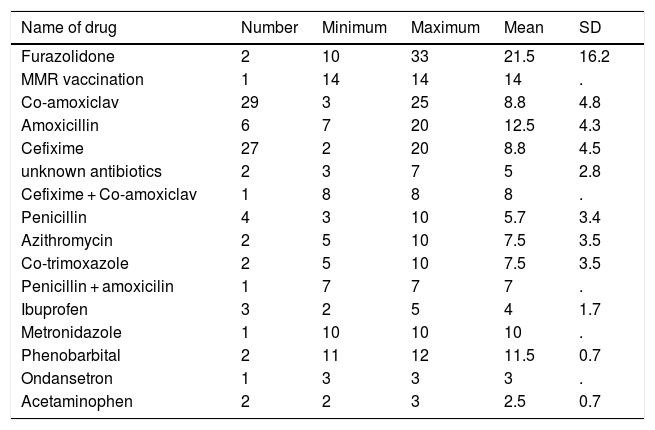

Joint involvement of the ankles, wrists and both legs and knees with 46 %, 28 % and 12 %, respectively, had the highest frequency among 60 patients with arthralgia. Involvement of finger and simultaneous involvement of elbows, wrists and ankles were the other cases of arthralgia in patients. Of the 81 patients with arthritis, 60 % had ankle arthritis and 27 % had ankle and wrist arthritis at the same time. The mean duration of onset of symptoms after consuming the medication was 8.8 ± 5.2 days, with a range of 12–33 days. The highest and lowest mean duration of onset of symptoms after consuming the medication with 21.5 and 2.5 days were Furazolidone and Acetaminophen, respectively.

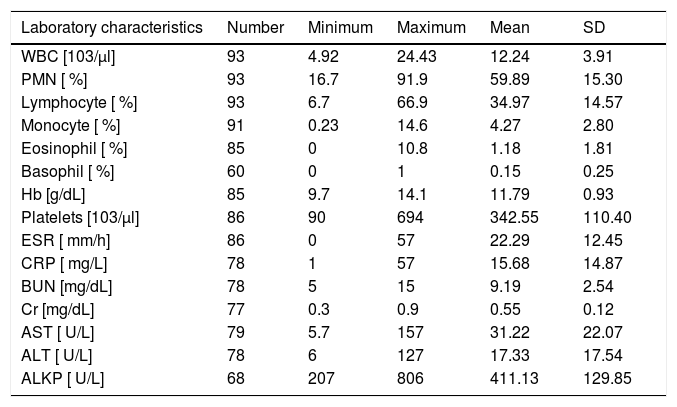

Table 2 shows the mean incidence of symptoms after consuming the medication separated by the type of medication consumed. Antihistamine with 96 % frequency was the most commonly prescribed treatment for the patients. Cetirizine (47 %) and the combination of Cetirizine & Hydroxyzine (37 %) were the most frequent types of antihistamine. Corticosteroid and Acetaminophen were also other common treatments prescribed for the patients. Table 3 shows information about laboratory indicators of patients.

Mean ± SD duration of onset of symptoms after consuming the medication.

| Name of drug | Number | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Furazolidone | 2 | 10 | 33 | 21.5 | 16.2 |

| MMR vaccination | 1 | 14 | 14 | 14 | . |

| Co-amoxiclav | 29 | 3 | 25 | 8.8 | 4.8 |

| Amoxicillin | 6 | 7 | 20 | 12.5 | 4.3 |

| Cefixime | 27 | 2 | 20 | 8.8 | 4.5 |

| unknown antibiotics | 2 | 3 | 7 | 5 | 2.8 |

| Cefixime + Co-amoxiclav | 1 | 8 | 8 | 8 | . |

| Penicillin | 4 | 3 | 10 | 5.7 | 3.4 |

| Azithromycin | 2 | 5 | 10 | 7.5 | 3.5 |

| Co-trimoxazole | 2 | 5 | 10 | 7.5 | 3.5 |

| Penicillin + amoxicilin | 1 | 7 | 7 | 7 | . |

| Ibuprofen | 3 | 2 | 5 | 4 | 1.7 |

| Metronidazole | 1 | 10 | 10 | 10 | . |

| Phenobarbital | 2 | 11 | 12 | 11.5 | 0.7 |

| Ondansetron | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | . |

| Acetaminophen | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2.5 | 0.7 |

Laboratory characteristics of the patients.

| Laboratory characteristics | Number | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WBC [103/μl] | 93 | 4.92 | 24.43 | 12.24 | 3.91 |

| PMN [ %] | 93 | 16.7 | 91.9 | 59.89 | 15.30 |

| Lymphocyte [ %] | 93 | 6.7 | 66.9 | 34.97 | 14.57 |

| Monocyte [ %] | 91 | 0.23 | 14.6 | 4.27 | 2.80 |

| Eosinophil [ %] | 85 | 0 | 10.8 | 1.18 | 1.81 |

| Basophil [ %] | 60 | 0 | 1 | 0.15 | 0.25 |

| Hb [g/dL] | 85 | 9.7 | 14.1 | 11.79 | 0.93 |

| Platelets [103/μl] | 86 | 90 | 694 | 342.55 | 110.40 |

| ESR [ mm/h] | 86 | 0 | 57 | 22.29 | 12.45 |

| CRP [ mg/L] | 78 | 1 | 57 | 15.68 | 14.87 |

| BUN [mg/dL] | 78 | 5 | 15 | 9.19 | 2.54 |

| Cr [mg/dL] | 77 | 0.3 | 0.9 | 0.55 | 0.12 |

| AST [ U/L] | 79 | 5.7 | 157 | 31.22 | 22.07 |

| ALT [ U/L] | 78 | 6 | 127 | 17.33 | 17.54 |

| ALKP [ U/L] | 68 | 207 | 806 | 411.13 | 129.85 |

This study described for the first time the information of children with Serum sickness-like reactions using the registry data of the Center for Asthma and Allergy in Tehran Children’s Medical Center. Our findings in this study showed that children with SSRL had urticaria, itching, and arthritis as the most common clinical symptoms about four days before hospitalization. Serum sickness is a hypersensitivity reaction due to the immune complexes and the activation of the complement which occurs classically with the intake of foreign proteins and horse-derived antibodies.4,14

Alternative medical treatments, antibodies modified by genetic engineering, and human biological factors have reduced the use of non-human antiserum and have reduced the risk of serum sickness and have increased the incidence of SSLRs due to the consumption of a variety of medications, especially antibiotics.2,15

According to the type of symptoms and differential diagnosis, exactly determining the incidence of SSLRs in the general population and clinic-based studies is difficult. The incidence of SSLRs is simultaneously estimated at 0.2 % for each period of medication consumption, up to 0.5 % for each period of several antibiotic consumption.6 In children, beta-lactam antibiotics (BL) are the most commonly used antibiotics and then non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications and non-beta-lactam antibiotics.16–19 An 84 % incidence of SSRL in children taking Cefaclor has been shown,20 but with decreasing the consumption of this antibiotic, the incidence of SSLRs due to the consumption of other antibiotics such as Penicillin, Tetracycline, Sulfonamide, Macrolides, Griseofulvin and Iitraconazole can be observed in recent years.21,22

Our findings showed that consumption of two antibiotics Co-amoxiclav and Cefixime or a combination of both had led to an incidence of 60 % of the cases of SSLRs. Amoxicillin and penicillin were also the other culprit antibiotics in the incidence of SSLRs which are commonly used antibiotics in the Iranian population.

In a clinic-based study, there was no report of receiving Co-amoxiclav or Cefixime among the 150 children between zero and sixteen years old with dermatological and articular reactions in the only pediatric hospital in Western Australia in a one-year period.20

In a survey of drug allergy on 117 children Mofid Hospital in Tehran by Mansouri et al., it was shown that 24 of the 27 children with SSLRs have been affected due to antibiotic consumption. Cefixime, Cotrimoxazole and furazolidone had also been the most commonly used antibiotics in those children.23 Moreover, in a similar report from a pediatric Rheumatology clinic in Turkey, 18 patients (62 %) of 29 children with SSLRs with the mean age of 100 months had a history of antibiotic consumption due to upper respiratory tract infection without referring to the type and the name of the antibiotic in a one-year period.24

The study by Gamboa at the Allergy Treatment Center in Spain also showed that after asthma and rhinitis, drug allergy is the third cause of referring to treatment. Their findings showed that the reaction to beta-lactam antibiotics was the most important cause of drug allergy in 81 % of children; while this rate has been reported to be 47 % in adults.19

Clinical symptoms of serum sickness manifest within one to three weeks after taking the medication as well as up to 36 h after taking it in some cases.25 Our findings showed that symptoms are manifested on average 8.8 days after taking the medication. The number of days - depending on the type of medication - had varied from 2 days for Ibuprofen to 33 days for Furazolidone. In other studies, the interval between receiving and the incidence of SSLRs has been reported to be 6–21 days as well as with a delay of 4–6 weeks in some cases.26–28

In our study, the symptoms of one patient were manifested after 25 days and another after 33 days. Although establishing the causality between the type of antibiotic and the incidence of symptoms is not possible without considering the type of infection and other clinical features of the child, it can be a valuable finding for the child’s parents as well as physician for the correct diagnosis of SSLRs considering that the mean incidence of symptoms of most of the antibiotics reported in this study is between 7.5 and 12.5 days after consuming. Also, rash, fever and arthralgia have been introduced as three main and important signs of SSRL in the study.29

In our study urticaria, itching, and arthritis had been the most common clinical symptoms in both sexes, while diarrhea, nausea, and sore throat had been the most common symptoms in males, and abdominal pain, urticaria, high temperature of edema, and arthralgia in females. Some studies that have investigated the effect of rabbit immunoglobulin or a specific vaccine on the incidence of SSLRs have reported a greater incidence in women and girls.12 On the contrary, although other studies have shown increased risk of pre-operation drug reactions in the female, a sex pattern for the incidence of SSRL in children cannot be generally conceived.30 Therefore, differences in the sex, frequency of incidence of SSRL and differences in the type of symptoms can be independent of the individuals’ sex, and other factors such as type of medication, type of disease, dose and duration of medication consumption can determine the type of symptoms in children.

ConclusionUndoubtedly, one of the basic needs of health and medical policies in the field of prevention and treatment of drug allergy in children is an accurate registry of data of the affected children and the production of high-quality epidemiological data. In this study using the registry data of Asthma and Allergy and Clinical Immunology in Tehran Children’s Medical Center showed for the first time that among the antibiotics reported by the patients’ parents, two antibiotics: Co-amoxiclav and Cefixime, are more prevalent and a review of prescribing these two antibiotics for the treatment of childhood infections is essential if this finding is confirmed by other Iranian scholars.

Author contributionsAzam Mohsenzadeh and Mohammad Gharagozlou conceived the design of the study and drafted the article. Mohammad Saatchi analyzed the data and interpreted them. Masoud Movahedi, Nima Parvaneh, Mansoureh Shariat and Asghar Aghamohammadi revised the article. All authors have given final approval of the version to be published.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

The authors would like to thank all the colleagues and staff of the Asthma and Allergy clinic in the children’s medical center of Tehran University of Medical Sciences.