Asthma is one of the most important diseases of childhood. The aim of this study was to evaluate the prevalence of asthma symptoms and risk factors affecting asthma.

MethodsIn a cross-sectional study design, 9991 children, aged 13–14 years in 61 primary schools in 32 districts of Istanbul were evaluated. Asthma prevalence among the children was assessed using the ISAAC protocol.

ResultsIn our study, a total of 10,894 questionnaires were distributed to 13–14 years old children, and of these 9991 questionnaires were suitable for analysis with an overall response rate of 91.7%. The rates of wheeze ever, wheezing in last 12 months and lifetime doctor diagnosed asthma prevalence were 17.4%, 9.0%, and 11.8%, respectively. There were 4746 boys (47.9%) and 5166 girls (52.1%) with M/F ratio of 0.92. Atopic family history, fewer than three siblings living at home, tonsillectomy or adenoidectomy history, consumption of fermented foods, mixed pickles, margarine and meat were found to be associated with an increased asthma risk. Use of paracetamol in the last 12 months, consumption of fruit and animal fats acted as a protective factor against asthma. The Mediterranean-style diet was not associated with the prevalence of asthma.

ConclusionsLifetime doctor diagnosed asthma prevalence was found to be 11.8% in 13–14 year olds. History of tonsillectomy and/or adenoidectomy and consumption of fermented foods, mixed pickles, margarine and meat may increase the symptoms of asthma. Usage of paracetamol and consumption of animal fats may be investigated as a protective factor against asthma.

Asthma is one of the most important diseases of childhood in developed countries. ISAAC, the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood, was founded to maximise the value of epidemiological research into asthma and allergic disease by establishing a standardised methodology and facilitating international collaboration.1,2

Diet is a relatively recently recognised potential risk factor for asthma. Some authors reported that there is an inverse relationship between the intake of citrus fruit,3 vegetables,4 apples and pears5 and the prevalence of asthma. Fish and fish products have also been associated with a lower prevalence of asthma.3,4,6,7 Increased consumption of linoleic acid, found in polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), is thought to be linked to asthma, eczema and allergic rhinitis8 because increased intake of linoleic acid leads to an increase in the synthesis of prostaglandin-E2 (PGE2), resulting in allergic sensitisation.9

The term “Mediterranean diet” refers to dietary patterns found in olive growing areas of the Mediterranean region. There are several variants of the Mediterranean diet, but some common components can be identified: a high ratio of monounsaturated to saturated fats; a high consumption rate of vegetables, fruits, pulses and grains; and moderate consumption of milk and dairy products.10 Results about the effect of the Mediterranean diet on the prevalence of asthma are conflicting.

There are not enough data showing the prevalence rate of asthma among 13–14 years old school children covering all districts in Istanbul. The aim of this study was to evaluate the prevalence of asthma symptoms using the ISAAC questionnaire, to investigate risk factors including dietary habits affecting asthma among 13–14 years old schoolchildren in all districts of Istanbul.

Materials and methodsStudy areaIstanbul is the biggest metropolis, being home to 13.5 million people; and one of the greatest business and cultural centres of Turkey. The city population consists of 1/7 of Turkey's population and its surface area is 11,868km2.11 It has 32 districts.

Study population and designThe number of primary school children attending Grade 8 was 181,271 in Istanbul. Of those children, 5% from each district were planned to include in the survey. The number of schools and children were calculated according to the number of children attending Grade 8 in each district. According to this calculation, a total of 10,894 children aged 13–14 years in 61 randomly selected primary schools of 32 districts without selection by urban or suburban residence or variations in socioeconomic status were surveyed by the ISAAC questionnaire. The 13–14 years age group was chosen to give a reflection of the period when mortality from asthma is more common and to enable the use of a self-completed questionnaire. Questionnaires were distributed by teachers for self-completion. The study was conducted in Istanbul, between March 2004 and July 2005.

QuestionnaireThe standardised core symptom questionnaire for 13–14 years olds was comprised of eight questions on symptoms relating to asthma.1,2 These questions were as follows:

- 1.

Have you ever had wheezing or whistling in the chest at any time in the past?

- 2.

Have you had wheezing or whistling in the chest in the last 12 months?

- 3.

How many attacks of wheezing have you had in the last 12 months? (None, 1–3, 4–12, more than 12)

- 4.

In the last 12 months, how often, on average, has your sleep been disturbed due to wheezing? (Never woken with wheezing, less than one night per week, one or more nights per week)

- 5.

In the last 12 months, has wheezing ever been severe enough to limit your speech to only one or two words at a time between breaths?

- 6.

Have you ever had asthma with doctor's confirmation (spastic bronchitis, allergic bronchitis)?

- 7.

In the last 12 months, has your chest sounded wheezy during or after exercise?

- 8.

In the last 12 months, have you had a dry cough at night, apart from a cough associated with a cold or chest infection?

Question 1 was used to estimate the prevalence of wheeze ever, question 2 was used to estimate the prevalence of wheeze in last 12 months, question 3 was used to estimate the prevalence of number of wheeze attacks in last 12 months, question 4 was used to estimate the prevalence of sleep disturbed by wheeze in last 12 months, question 5 was used to estimate the prevalence of wheeze limiting speech in last 12 months, question 6 was used to estimate the prevalence of lifetime doctor diagnosed asthma, question 7 was used to estimate the prevalence of wheeze after exercise in last 12 months and question 8 was used to estimate the prevalence of waking with cough in last 12 months.

The questionnaire was translated into Turkish and used. As in the previous studies, the definition of asthma was accepted as self-reporting of diagnosed asthma with a physician's confirmation.12,13 In general, doctors used the terms “allergic bronchitis” or “spastic bronchitis” instead of asthma.12,13 For this reason, both of these terms were accepted as asthma in evaluation. There have been many studies carried out in Turkey using the modified version of the ISAAC questionnaire.12–15

An additional questionnaire was prepared to identify demographic features and potential risk factors, including: sex, atopic family history, time television watched during a week, paracetamol use in last 12 months, number of siblings living at home, being born in Istanbul, living period in Istanbul, education level of child's mother and father, presence of domestic animals at home, keeping fish, cat, dog and bird at home during last 12 months, smoking of child's mother (or guardian), smoking of child's father, tonsillectomy and adenotonsillectomy.

Dietary intake was estimated by using additionally a semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire. Consumption of foods including potatoes, rice, cereal, pasta, vegetables, fish, other sea foods, fruits, tomatoes, nuts, olive oil, fish oil, boiled grape juice, fermented drinks made from millets and various seeds, hamburger, potato chips, crackers, chocolates, lollipops, candies, cookies, muffins, margarine, eggs, animal fats, milk and dairy products, meat, PUFAs (butter), sun-flower oil, corn oil, tea, broad bean and olives were asked. Analysis of diet variables was determined by frequency of consumption of foods in three groups including: “never or occasionally”, “once or twice per week” and “three or more times a week”.

We calculated a MD score based on the work of García-Marcos et al.16 Fruit, seafood, vegetables, pulses, cereals, pasta, rice, and potatoes were considered Mediterranean foods and scored 0, 1, or 2 points, ranging from the least frequent to the most frequent intake: never or occasionally (0), 1–2 times/wk (1), and 3 or more times/wk (2). Meat, milk, and fast food were considered non-Mediterranean foods and scored 0, 1, or 2 points, ranging from the most frequent to the least frequent consumption: 3 or more times/wk (0) 1–2 times/wk (1) and never or occasionally (2). In all the analyses, the MD score was the sum of the points of each food, ranging from 0 to 22; the higher the score, the greater the adherence to the MD.

Statistical analysisStatistical significance of differences was assessed by the chi-square test. A p value less than 0.05 was considered as significant. Prevalence estimates were calculated by dividing positive responses to the given question by the total number of completed questionnaires, while missing or inconsistent responses were excluded from subsequent univariate analyses according to ISAAC recommendations.2 The children with no response for a question were excluded from the analysis of the relevant variable. Prevalence of allergic diseases’ symptoms and risk factors were calculated with 95% confidence interval (CI). The relation between risk factors and doctor diagnosed asthma prevalence was performed by univariate analysis using chi-square tests with univariate odds ratio (uOR) and its 95% CI. Significant factors from the univariate analysis were taken into multivariate logistic regression analysis to assess the independent effects of risk factors on doctor diagnosed asthma with adjusted odds ratio (aOR) and its 95% CI.

The MD score between children with asthma and children without asthma was compared using the independent T test. Significant factors from the univariate analysis were taken into multivariate logistic regression analysis to assess the independent effects of risk factors on asthma.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis for relation between the frequency of intake of foods and asthma was applied separately from risk factors. Odds ratios for suffering from doctor-diagnosed asthma according to the consumption of each food (≥3 times/week compared with never or occasionally and 1–2 times/week) were adjusted by logistic regression. The SPSS software package version 12.0 was used for all statistical analyses.

Ethical considerationThe study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Istanbul University, Istanbul School of Medicine.

ResultsIn our study, of 10,894 questionnaires, 3515 were distributed to 13–14 years old children to 22 schools in 11 districts in the Asian region of Istanbul and 7379 were distributed to 13–14 years old children to 39 schools in 21 districts in the European region of Istanbul; 10,298 questionnaires were completed by themselves with an overall response rate of 94.5%, and 9991 questionnaires with 3255 in Asian region and 6736 in European districts were suitable for analysis with an overall response of 91.7%.

There were 4746 boys (47.9%) and 5166 girls (52.1%) with a M/F ratio of 0.92.

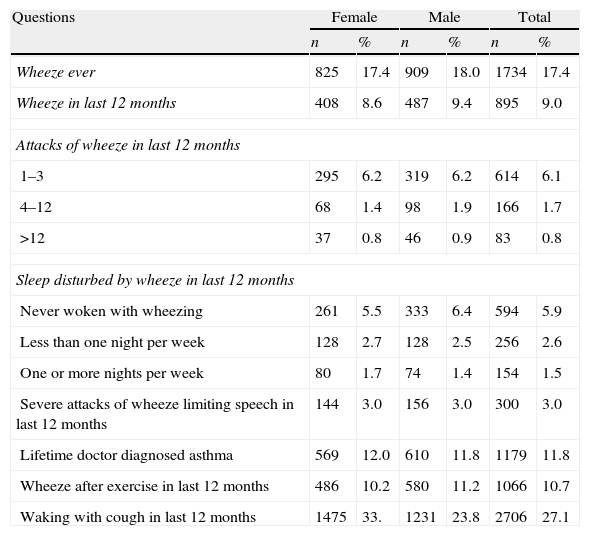

In our study, the prevalence of wheeze ever, wheeze in last 12 months, and lifetime doctor-diagnosed asthma were 17.4%, 9.0%, and 11.8%, respectively. These rates for Asian and European regions were 15.7–8.2–11.4% and 18.3–9.4–12.1%, respectively. The rates of asthma and other asthma-related symptoms prevalence in Istanbul are given in Table 1.

Prevalences of wheeze, asthma, and other symptoms (n: 9991).

| Questions | Female | Male | Total | |||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Wheeze ever | 825 | 17.4 | 909 | 18.0 | 1734 | 17.4 |

| Wheeze in last 12 months | 408 | 8.6 | 487 | 9.4 | 895 | 9.0 |

| Attacks of wheeze in last 12 months | ||||||

| 1–3 | 295 | 6.2 | 319 | 6.2 | 614 | 6.1 |

| 4–12 | 68 | 1.4 | 98 | 1.9 | 166 | 1.7 |

| >12 | 37 | 0.8 | 46 | 0.9 | 83 | 0.8 |

| Sleep disturbed by wheeze in last 12 months | ||||||

| Never woken with wheezing | 261 | 5.5 | 333 | 6.4 | 594 | 5.9 |

| Less than one night per week | 128 | 2.7 | 128 | 2.5 | 256 | 2.6 |

| One or more nights per week | 80 | 1.7 | 74 | 1.4 | 154 | 1.5 |

| Severe attacks of wheeze limiting speech in last 12 months | 144 | 3.0 | 156 | 3.0 | 300 | 3.0 |

| Lifetime doctor diagnosed asthma | 569 | 12.0 | 610 | 11.8 | 1179 | 11.8 |

| Wheeze after exercise in last 12 months | 486 | 10.2 | 580 | 11.2 | 1066 | 10.7 |

| Waking with cough in last 12 months | 1475 | 33. | 1231 | 23.8 | 2706 | 27.1 |

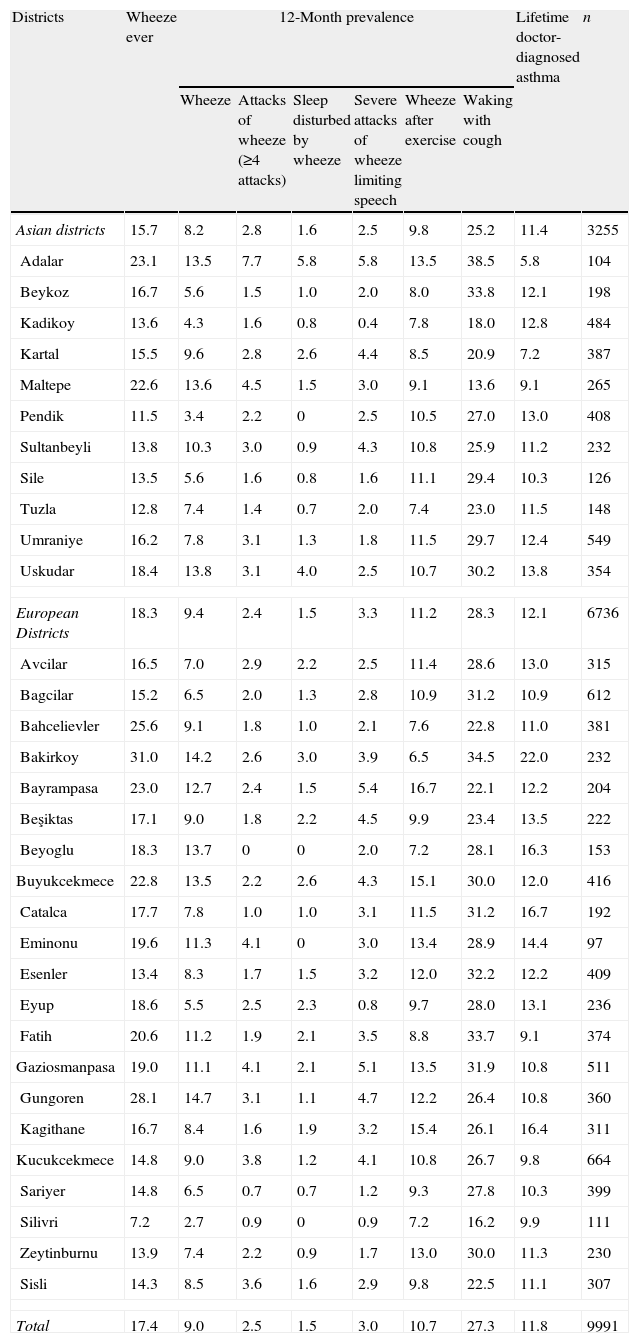

Prevalence rates of wheeze ever, severe attacks of wheeze limiting speech in last 12 months, wheeze after exercise in last 12 months, and waking with cough in last 12 months in European region were significantly higher than those in Asian region (P=0.01, P=0.033, P=0.028 and P=0.01, respectively). Prevalence rates of wheeze in last 12 months and asthma in European region were higher than those in the Asian region but this difference was not significant statistically (P=0.46 and P=0.15, respectively). However, prevalence rate of 4 or more wheezing attacks in last 12 months in the Asian region was higher than that of the European region (P=0.021). The prevalence rate of sleep disturbed by wheeze in last 12 months was similar in two regions (P=0.25).

The between-district variation (32 districts) was wide for all asthma symptoms prevalence. The rate of variation was 5.4 for wheeze in last 12 months (range: 2.7–14.7) with the lowest rates (<5%) in Kadıkoy, Pendik, Bagcilar, Eyup and Silivri and the highest rate (>13%) in Adalar, Maltepe, Uskudar, Bakirkoy, Beyoglu, Buyukcekmece and Gungoren. The rate was 3.79 (range: 5.8–22.0) for asthma, with the lowest rate (<7%) in Adalar and the highest rates (>16%) in Bakirkoy, Beyoglu and Catalca. The rates of asthma and other asthma related symptoms’ prevalence of Istanbul are given in Tables 1 and 2.

Prevalences of wheeze, asthma, and other symptoms in districts of Istanbul.

| Districts | Wheeze ever | 12-Month prevalence | Lifetime doctor-diagnosed asthma | n | |||||

| Wheeze | Attacks of wheeze (≥4 attacks) | Sleep disturbed by wheeze | Severe attacks of wheeze limiting speech | Wheeze after exercise | Waking with cough | ||||

| Asian districts | 15.7 | 8.2 | 2.8 | 1.6 | 2.5 | 9.8 | 25.2 | 11.4 | 3255 |

| Adalar | 23.1 | 13.5 | 7.7 | 5.8 | 5.8 | 13.5 | 38.5 | 5.8 | 104 |

| Beykoz | 16.7 | 5.6 | 1.5 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 8.0 | 33.8 | 12.1 | 198 |

| Kadikoy | 13.6 | 4.3 | 1.6 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 7.8 | 18.0 | 12.8 | 484 |

| Kartal | 15.5 | 9.6 | 2.8 | 2.6 | 4.4 | 8.5 | 20.9 | 7.2 | 387 |

| Maltepe | 22.6 | 13.6 | 4.5 | 1.5 | 3.0 | 9.1 | 13.6 | 9.1 | 265 |

| Pendik | 11.5 | 3.4 | 2.2 | 0 | 2.5 | 10.5 | 27.0 | 13.0 | 408 |

| Sultanbeyli | 13.8 | 10.3 | 3.0 | 0.9 | 4.3 | 10.8 | 25.9 | 11.2 | 232 |

| Sile | 13.5 | 5.6 | 1.6 | 0.8 | 1.6 | 11.1 | 29.4 | 10.3 | 126 |

| Tuzla | 12.8 | 7.4 | 1.4 | 0.7 | 2.0 | 7.4 | 23.0 | 11.5 | 148 |

| Umraniye | 16.2 | 7.8 | 3.1 | 1.3 | 1.8 | 11.5 | 29.7 | 12.4 | 549 |

| Uskudar | 18.4 | 13.8 | 3.1 | 4.0 | 2.5 | 10.7 | 30.2 | 13.8 | 354 |

| European Districts | 18.3 | 9.4 | 2.4 | 1.5 | 3.3 | 11.2 | 28.3 | 12.1 | 6736 |

| Avcilar | 16.5 | 7.0 | 2.9 | 2.2 | 2.5 | 11.4 | 28.6 | 13.0 | 315 |

| Bagcilar | 15.2 | 6.5 | 2.0 | 1.3 | 2.8 | 10.9 | 31.2 | 10.9 | 612 |

| Bahcelievler | 25.6 | 9.1 | 1.8 | 1.0 | 2.1 | 7.6 | 22.8 | 11.0 | 381 |

| Bakirkoy | 31.0 | 14.2 | 2.6 | 3.0 | 3.9 | 6.5 | 34.5 | 22.0 | 232 |

| Bayrampasa | 23.0 | 12.7 | 2.4 | 1.5 | 5.4 | 16.7 | 22.1 | 12.2 | 204 |

| Beşiktas | 17.1 | 9.0 | 1.8 | 2.2 | 4.5 | 9.9 | 23.4 | 13.5 | 222 |

| Beyoglu | 18.3 | 13.7 | 0 | 0 | 2.0 | 7.2 | 28.1 | 16.3 | 153 |

| Buyukcekmece | 22.8 | 13.5 | 2.2 | 2.6 | 4.3 | 15.1 | 30.0 | 12.0 | 416 |

| Catalca | 17.7 | 7.8 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 3.1 | 11.5 | 31.2 | 16.7 | 192 |

| Eminonu | 19.6 | 11.3 | 4.1 | 0 | 3.0 | 13.4 | 28.9 | 14.4 | 97 |

| Esenler | 13.4 | 8.3 | 1.7 | 1.5 | 3.2 | 12.0 | 32.2 | 12.2 | 409 |

| Eyup | 18.6 | 5.5 | 2.5 | 2.3 | 0.8 | 9.7 | 28.0 | 13.1 | 236 |

| Fatih | 20.6 | 11.2 | 1.9 | 2.1 | 3.5 | 8.8 | 33.7 | 9.1 | 374 |

| Gaziosmanpasa | 19.0 | 11.1 | 4.1 | 2.1 | 5.1 | 13.5 | 31.9 | 10.8 | 511 |

| Gungoren | 28.1 | 14.7 | 3.1 | 1.1 | 4.7 | 12.2 | 26.4 | 10.8 | 360 |

| Kagithane | 16.7 | 8.4 | 1.6 | 1.9 | 3.2 | 15.4 | 26.1 | 16.4 | 311 |

| Kucukcekmece | 14.8 | 9.0 | 3.8 | 1.2 | 4.1 | 10.8 | 26.7 | 9.8 | 664 |

| Sariyer | 14.8 | 6.5 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 1.2 | 9.3 | 27.8 | 10.3 | 399 |

| Silivri | 7.2 | 2.7 | 0.9 | 0 | 0.9 | 7.2 | 16.2 | 9.9 | 111 |

| Zeytinburnu | 13.9 | 7.4 | 2.2 | 0.9 | 1.7 | 13.0 | 30.0 | 11.3 | 230 |

| Sisli | 14.3 | 8.5 | 3.6 | 1.6 | 2.9 | 9.8 | 22.5 | 11.1 | 307 |

| Total | 17.4 | 9.0 | 2.5 | 1.5 | 3.0 | 10.7 | 27.3 | 11.8 | 9991 |

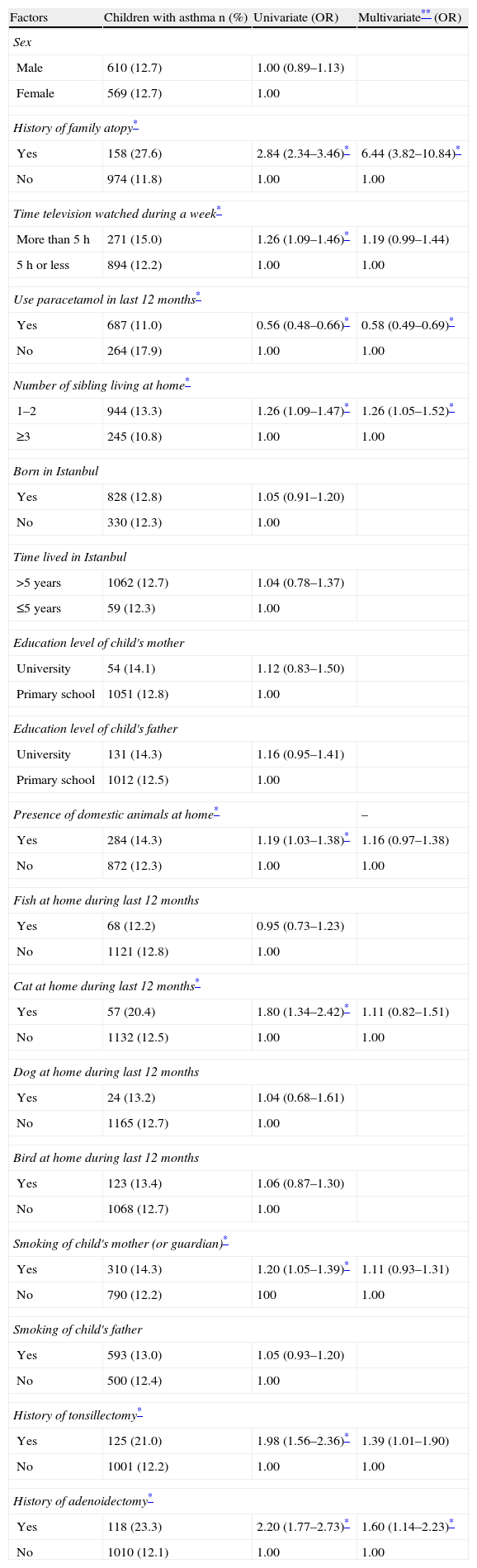

History of family atopy (aOR=6.44, 95% CI=3.82–10.84), paracetamol usage in the last 12 months (aOR=0.58, 95% CI=0.49–0.69), having fewer than three siblings living at home (aOR=1.26, 95% CI=1.05–1.52), history of tonsillectomy (aOR=1.39, 95% CI=1.01–1.90), and history of adenoidectomy (aOR=1.60, 95% CI=1.14–2.23), were independently associated with asthma by multivariate analysis.

Although time spent watching television per week, presence of domestic animals at home, cat at home during last 12 months and smoking of child's mother (or guardian) were associated with asthma by univariate analysis, these risk factors showed no statistical significance by multivariate analysis.

There was no statistically significant difference between asthmatics and non-asthmatics by sex, region of district, being born in Istanbul, time lived in Istanbul, education level of child's mother and father, presence of fish, dog and bird at home during last 12 months, and smoking of child's father. Risk factors affecting prevalence of asthma are presented in Table 3.

Risk factors affecting the prevalence of doctor-diagnosed asthma.

| Factors | Children with asthma n (%) | Univariate (OR) | Multivariate** (OR) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 610 (12.7) | 1.00 (0.89–1.13) | |

| Female | 569 (12.7) | 1.00 | |

| History of family atopy* | |||

| Yes | 158 (27.6) | 2.84 (2.34–3.46)* | 6.44 (3.82–10.84)* |

| No | 974 (11.8) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Time television watched during a week* | |||

| More than 5h | 271 (15.0) | 1.26 (1.09–1.46)* | 1.19 (0.99–1.44) |

| 5h or less | 894 (12.2) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Use paracetamol in last 12 months* | |||

| Yes | 687 (11.0) | 0.56 (0.48–0.66)* | 0.58 (0.49–0.69)* |

| No | 264 (17.9) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Number of sibling living at home* | |||

| 1–2 | 944 (13.3) | 1.26 (1.09–1.47)* | 1.26 (1.05–1.52)* |

| ≥3 | 245 (10.8) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Born in Istanbul | |||

| Yes | 828 (12.8) | 1.05 (0.91–1.20) | |

| No | 330 (12.3) | 1.00 | |

| Time lived in Istanbul | |||

| >5 years | 1062 (12.7) | 1.04 (0.78–1.37) | |

| ≤5 years | 59 (12.3) | 1.00 | |

| Education level of child's mother | |||

| University | 54 (14.1) | 1.12 (0.83–1.50) | |

| Primary school | 1051 (12.8) | 1.00 | |

| Education level of child's father | |||

| University | 131 (14.3) | 1.16 (0.95–1.41) | |

| Primary school | 1012 (12.5) | 1.00 | |

| Presence of domestic animals at home* | – | ||

| Yes | 284 (14.3) | 1.19 (1.03–1.38)* | 1.16 (0.97–1.38) |

| No | 872 (12.3) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Fish at home during last 12 months | |||

| Yes | 68 (12.2) | 0.95 (0.73–1.23) | |

| No | 1121 (12.8) | 1.00 | |

| Cat at home during last 12 months* | |||

| Yes | 57 (20.4) | 1.80 (1.34–2.42)* | 1.11 (0.82–1.51) |

| No | 1132 (12.5) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Dog at home during last 12 months | |||

| Yes | 24 (13.2) | 1.04 (0.68–1.61) | |

| No | 1165 (12.7) | 1.00 | |

| Bird at home during last 12 months | |||

| Yes | 123 (13.4) | 1.06 (0.87–1.30) | |

| No | 1068 (12.7) | 1.00 | |

| Smoking of child's mother (or guardian)* | |||

| Yes | 310 (14.3) | 1.20 (1.05–1.39)* | 1.11 (0.93–1.31) |

| No | 790 (12.2) | 100 | 1.00 |

| Smoking of child's father | |||

| Yes | 593 (13.0) | 1.05 (0.93–1.20) | |

| No | 500 (12.4) | 1.00 | |

| History of tonsillectomy* | |||

| Yes | 125 (21.0) | 1.98 (1.56–2.36)* | 1.39 (1.01–1.90) |

| No | 1001 (12.2) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| History of adenoidectomy* | |||

| Yes | 118 (23.3) | 2.20 (1.77–2.73)* | 1.60 (1.14–2.23)* |

| No | 1010 (12.1) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

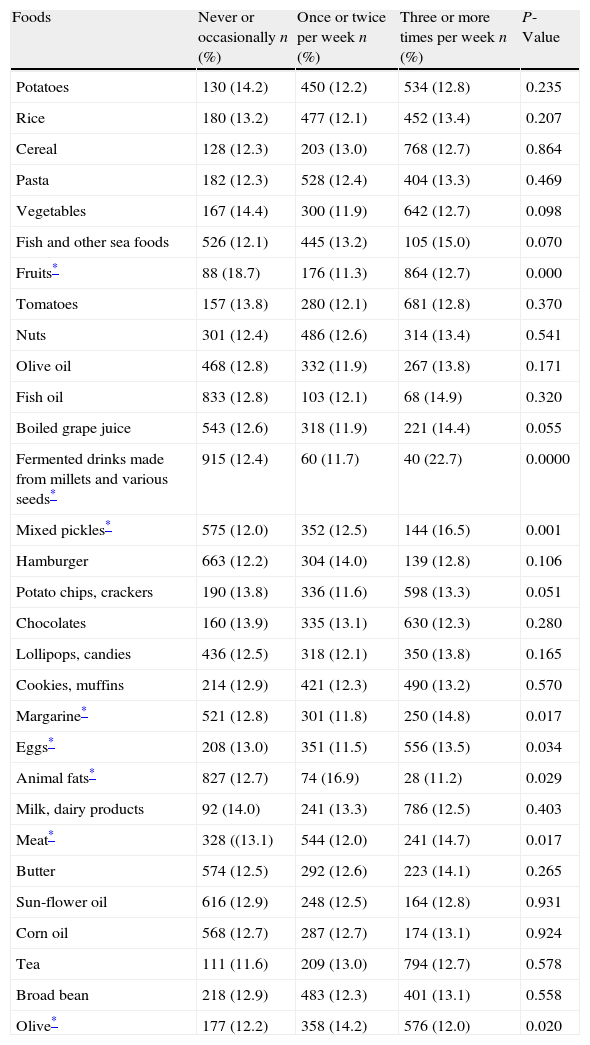

According to the univariate analysis, foods, which included fruits, fermented drinks made from millets and various seeds, mix pickles, margarine, eggs, animal fats, meat and olive, were associated with asthma prevalence (Table 4).

Relationship between the prevalence of doctor-diagnosed asthma and dietary habits of Turkish children.

| Foods | Never or occasionally n (%) | Once or twice per week n (%) | Three or more times per week n (%) | P-Value |

| Potatoes | 130 (14.2) | 450 (12.2) | 534 (12.8) | 0.235 |

| Rice | 180 (13.2) | 477 (12.1) | 452 (13.4) | 0.207 |

| Cereal | 128 (12.3) | 203 (13.0) | 768 (12.7) | 0.864 |

| Pasta | 182 (12.3) | 528 (12.4) | 404 (13.3) | 0.469 |

| Vegetables | 167 (14.4) | 300 (11.9) | 642 (12.7) | 0.098 |

| Fish and other sea foods | 526 (12.1) | 445 (13.2) | 105 (15.0) | 0.070 |

| Fruits* | 88 (18.7) | 176 (11.3) | 864 (12.7) | 0.000 |

| Tomatoes | 157 (13.8) | 280 (12.1) | 681 (12.8) | 0.370 |

| Nuts | 301 (12.4) | 486 (12.6) | 314 (13.4) | 0.541 |

| Olive oil | 468 (12.8) | 332 (11.9) | 267 (13.8) | 0.171 |

| Fish oil | 833 (12.8) | 103 (12.1) | 68 (14.9) | 0.320 |

| Boiled grape juice | 543 (12.6) | 318 (11.9) | 221 (14.4) | 0.055 |

| Fermented drinks made from millets and various seeds* | 915 (12.4) | 60 (11.7) | 40 (22.7) | 0.0000 |

| Mixed pickles* | 575 (12.0) | 352 (12.5) | 144 (16.5) | 0.001 |

| Hamburger | 663 (12.2) | 304 (14.0) | 139 (12.8) | 0.106 |

| Potato chips, crackers | 190 (13.8) | 336 (11.6) | 598 (13.3) | 0.051 |

| Chocolates | 160 (13.9) | 335 (13.1) | 630 (12.3) | 0.280 |

| Lollipops, candies | 436 (12.5) | 318 (12.1) | 350 (13.8) | 0.165 |

| Cookies, muffins | 214 (12.9) | 421 (12.3) | 490 (13.2) | 0.570 |

| Margarine* | 521 (12.8) | 301 (11.8) | 250 (14.8) | 0.017 |

| Eggs* | 208 (13.0) | 351 (11.5) | 556 (13.5) | 0.034 |

| Animal fats* | 827 (12.7) | 74 (16.9) | 28 (11.2) | 0.029 |

| Milk, dairy products | 92 (14.0) | 241 (13.3) | 786 (12.5) | 0.403 |

| Meat* | 328 ((13.1) | 544 (12.0) | 241 (14.7) | 0.017 |

| Butter | 574 (12.5) | 292 (12.6) | 223 (14.1) | 0.265 |

| Sun-flower oil | 616 (12.9) | 248 (12.5) | 164 (12.8) | 0.931 |

| Corn oil | 568 (12.7) | 287 (12.7) | 174 (13.1) | 0.924 |

| Tea | 111 (11.6) | 209 (13.0) | 794 (12.7) | 0.578 |

| Broad bean | 218 (12.9) | 483 (12.3) | 401 (13.1) | 0.558 |

| Olive* | 177 (12.2) | 358 (14.2) | 576 (12.0) | 0.020 |

The mean MD scores for children with asthma and children without asthma were 12.51 and 12.53, respectively. There was no statistically significant difference in this score between asthmatic and non-asthmatic children (P=0.85).

Foods associated with asthma were tested in logistic regression analysis with adjusted odds. Asthma prevalence in children consuming fruits and animal fats three or more times a week was lower than in those with these foods consumed never or occasionally (aOR=0.66, 95% CI=0.48–0.93; and aOR=0.58, 95% CI=0.35–0.93, respectively. When animal fats or olive were consumed three or more times a week, asthma prevalence was lower than it was in those who consumed these foods once or twice per week (aOR=0.48, 95% CI=0.28–0.84; and aOR=0.79, 95% CI=0.66–0.94, respectively). When fermented drinks made from millets and various seeds, mix pickles and margarine were consumed three or more times a week, asthma prevalence was higher than it was in those who consumed these foods never or occasionally, or once to twice per week. When meat was consumed three or more times a week, asthma prevalence was higher than it was in those who consumed these foods once to twice per week (aOR=1.26, 95% CI=1.04–1.52) (Table 5).

Effects of foods on asthma prevalence, when foods consumed three or more times a week compared to never or occasionally and once to twice per week.

| Foods | Never or occasionally (aOR) | P-Value | Once or twice per week (aOR) | P-Value |

| Fruits | 0.66 (0.48–0.93)* | 0.017 | 1.06 (0.86–1.30) | 0.57 |

| Fermented drinks made from millets and various seeds* | 2.25 (1.50–3.38)* | <0.01 | 2.51 (1.54–4.11)* | <0.01 |

| Mixed pickles* | 1.49 (1.17–1.89)* | 0.001 | 1.42 (1.11–1.81)* | 0.005 |

| Margarine* | 1.24 (1.02–1.51)* | 0.033 | 1.28 (1.04–1.58)* | 0.020 |

| Eggs | 0.90 (0.73–1.12) | 0.35 | 1.13 (0.95–1.34) | 0.164 |

| Animal fats* | 0.58 (0.35–0.93)* | 0.025 | 0.48 (0.28–0.84)* | 0.010 |

| Meat* | 1.12 (0.90–1.40) | 0.29 | 1.26 (1.04–1.52)* | 0.015 |

| Olive* | 0.97 (0.78–1.22) | 0.82 | 0.79 (0.66–0.94)* | 0.007 |

This study has given valuable information about the prevalence and risk factors of asthma in 13–14 years old schoolchildren living in Istanbul. Our study is the most comprehensive one evaluating the prevalence of asthma in 13–14 years age group covering all districts of Istanbul.

Prevalence of childhood asthma among 13–14 year old schoolchildren in different regions of Turkey ranged from 2.1% to 7.0%.14,17 In our study, the prevalence of asthma in 13–14 years old children was found to be 11.8%. When we compared the results of this study with previous studies using the ISAAC method in Istanbul, the prevalence of doctor-diagnosed asthma was lower than the results of the 2004 study (17.8%),13 this rate was higher than the results of the 1995 (9.8%)12 and 1996 studies (4.0%).15 This can be explained in part by the difference in age groups, since a large proportion of asthmatic children aged 13–14 would lose their asthma symptoms when they grew up. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study evaluating the prevalence of asthma in only 13–14 year old children in Istanbul. As this is the first reported study which has been done in this age group in Istanbul, it is not possible to compare the difference of prevalence with previous studies. When compared with other studies of 13–14 year olds from different countries, the rate of asthma prevalence in our study was similar to results in Austria (11.8%) and Belgium (12%), it was lower than the prevalence in the UK (31%) and the USA (22.9%) and higher than in China (4.3%), Indonesia (2.1%) and Mexico (6.6%).18

Asthma-related symptom prevalence rates were generally reported to be similar in centres within the same country, but in some countries, such as India, Ethiopia, Italy and Spain, large variations were detected between centres.1 There were also wide variations in the prevalence of asthma-related symptom within regions, especially within European and Asian districts in the current study 5.4 (range 2.7–14.7). Rates of asthma-related symptoms prevalence in European districts were higher than those in Asian districts. The reason for this may be explained by more crowed districts and more traffic on the European side.

Asthma is a complex disease, modified by genetic background and affected by exposure to environmental agents. The results of this study may also provide an opportunity for investigation of possible causative factors for asthma and related symptoms. As expected, we found atopic heredity as the most prominent risk factor for asthma.

A growing number of studies have documented that frequent acetaminophen usage is associated with an increased risk of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis and atopic eczema.19 Beasley et al. reported that paracetamol use is an important risk factor for the development and/or maintenance of asthma, rhinoconjunctivitis, and eczema in adolescent children.20 Gonzalez-Barcala et al. reported that paracetamol consumption is associated with a significant increase in asthma symptoms and this effect is greater when the drug is used more often.21 Similarly, Vlaski et al.22 reported that the risk of asthma may be increased by exposure to paracetamol in adolescents. In our study, we found a negative association between paracetamol use and the prevalence of asthma and we could not interpret the reasons for this result. This unexpected result might be explained by the low consumption of paracetamol of the study population.

According to parity hypothesis an increased household size is associated with a decreased risk of allergic diseases.23 Goldberg S et al. examined the relationship between asthma prevalence and family size and they reported that asthma prevalence is inversely related to the number of children in families with four or more children.24 In a recent study from Israel, a significant inverse relationship between the number of children in the family and the prevalence of asthma was shown. In this study, prevalence of asthma was 8.7% in families with 1 or 2 children and 1.9% in families with 9 or more children.25 In our study, having three or fewer siblings was found to be significantly associated with increased prevalence of asthma confirming parity hypothesis.

The relationship between adenoidectomy or tonsillectomy and asthma is still under debate. Surgical removal of these tissues may cause a reduction in stimulation of the Th1-type immune response and may lead to a rise in Th2-type-mediated atopic diseases according to “hygiene hypothesis”.26 Allergy and sensitivity to different kinds of allergens are thought to be risk factors for adenoid hypertrophy in children27 which is also a risk factor for adenoidectomy. Akcay et al. reported that children who are allergic may have an increased tendency to upper airway diseases since the airways of asthmatics are more vulnerable due to allergic inflammation. Most asthmatic children might also have allergic rhinitis.28 Children with allergic rhinitis usually have nasal congestion causing them to breathe through the mouth. This might lead to frequent tonsillopharyngitis and enlarged tonsils resulting in tonsillectomy. Akcay et al. also reported tonsillar hypertrophy might be a risk factor for asthma-related symptoms29 but they found no relationship between tonsillectomy and/or adenoidectomy asthma symptoms. In a longitudinal birth cohort study, no association between adenoidectomy and/or tonsillectomy in childhood and asthma, allergic rhinitis, and eczema at 21 years of age was found.30 On the other hand, Busino RS et al. showed a statistically significant improvement in asthma severity including mean hospital visits, systemic steroid administration, asthma medication use, and childhood asthma control test scores (P<0.01) after adenotonsillectomy.31 In the current study, we found that tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy was significantly associated with increased risk of asthma with multivariate analysis. This result could be related with higher indication rate of adenoidectomy and/or tonsillectomy in allergic children.

Exposure to allergens is reportedly associated with an increased risk of allergic diseases. Brunekreef et al.32 reported that current exposure to cats and dogs combined, and to dogs only, are risk factors for symptoms reported by asthmatic adolescents. On the other hand, Prodanovic et al. did not find a relationship between pet ownership and asthma.33 In our study, the presence of fish, cats, dogs and birds at home was not related to an increased prevalence of asthma.

The influence of the exposure to tobacco smoke on the development of asthma has been investigated at different stages of life. The results of studies have been contradictory when investigating the relationship between passive exposure to cigarette and the prevalence of asthma. There are studies that show a direct association,34 and conversely, a protective effect has also been reported.35 In the current study, no association was found between passive smoking and the prevalence of asthma.

Other evaluated risk factors including sex, watching television more than three hours a day, region of district, being born in Istanbul, time spent in Istanbul and education level of the child's parents were not found to be associated with asthma prevalence in our study.

It was reported that food may have an important role in developing asthma because of epigenetic effects36 thus increasing the prevalence of asthma and allergy that can be related to dietary habits.37

Increased consumption of linoleic acid, found in PUFAs, is thought to be linked to asthma, eczema and allergic rhinitis.8 Miyake et al. reported that dietary saturated fat intake was positively associated with symptoms of asthma.38 In our study, consumption of animal fats, a source of saturated fatty acids was found to be associated with decreased prevalence of asthma. This may be explained with low consumption of animal fats by asthmatic teenagers in the study group, taking their doctors’ advice but this result should be confirmed with other studies.

Many studies show that the consumption of foods containing antioxidants (fruit and vegetables) acts as a protective factor against atopy.37,39 Frequent consumption of fruit may be protective against asthma due to its antioxidant effects. In our study, a significant inverse relationship was found between asthma prevalence and consumption of fruit. Fruit consumed three or more times a week was found to be a protective factor for asthma compared with eating occasionally or never. This result was in concordance with the previous studies.

In the current study, fermented drinks made from millets and various seeds and mix pickles were associated with an increased asthma risk. Fermented drinks were made from millets and various seeds including roasted chickpeas, nuts and sugar. Mixed pickles included vegetables, salt and acidic vinegar. Additionally, it includes chemical substances released as a result of interaction between acid and pickles. Fermented foods, acid and chemical substances may change intestinal flora. These foods may act as possible causative agents for asthma.

There is evidence that the Mediterranean diet is a potential protective factor for current severe asthma in girls16 and asthma ever40,41 and current wheezing.40,42 In our study, the Mediterranean diet was not associated with the prevalence of asthma, as has been reported by Chatzi43 and Gonzalez Barcala and et al.44

The limitations of this study were that the children were categorised with asthma based on a questionnaire, without confirming the diagnosis according to their medical histories or to lung function tests. Another limitation of this study was that ISAAC protocol questions have not been validated by us nor by our Turkish colleagues who used them in their studies. We believe that the translation of the phrases would not cause any great discrepancy that would have influenced our results, since translation was undertaken by people fluent in both Turkish and English and there were no “vague phrases” that would have caused any major interobserver variability in the translation.

In conclusion, our study has provided valuable information about the prevalence of asthma in 13–14 years old schoolchildren living in Istanbul. Asthma prevalence found in this study was lower than the results of previous studies which were done in Istanbul. Atopic family history, fewer than three siblings living at home, history of tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy are found to be significantly related with increased asthma prevalence. Usage of paracetamol in adolescents was found to be associated with decreased asthma prevalence and this result should be investigated with new studies. In this study, although the consumption of fruit and animal fats may act as a protective factor against asthma, the fermented foods, mixed pickles, margarine and meat were found to be associated with an increased prevalence of asthma. Additionally, no association was found between the Mediterranean diet and the prevalence of asthma.

Ethical disclosuresOur present survey was approved by the ethics committee of of Istanbul University, Istanbul School of Medicine.

Protection of human subjects and animals in researchWe declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Patients’ data protectionWe declare that we have followed the protocols of our work centre on the publication of patient data and that all the patients included in the study have received sufficient information and have given their informed consent in writing to participate in that study.

Right to privacy and informed consentWe have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects mentioned in the article. The author for correspondence is in possession of this document. The schoolchildren signed a consent form in order to participate to the study.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.