Limited studies conducted on children <2 years old and/or involving a skin prick test (SPT) for fresh milk (FM) have examined the predictive value of allergometric tests for outgrowth of cow's milk allergy (CMA). We investigated the optimal decision points for outgrowth (ODPfo) with SPT for commercial cow's milk extract (CE) and FM and specific immunoglobulin E (sIgE) levels for milk proteins to predict outgrowing allergy in children <2 years old.

MethodsSPTs for CE and FM, tests for sIgEs (cow's milk, casein, α-lactoalbumin, β-lactoglobulin) and oral food challenges (OFC) were performed in children referred for evaluation of suspected CMA, and 15 months after diagnosis.

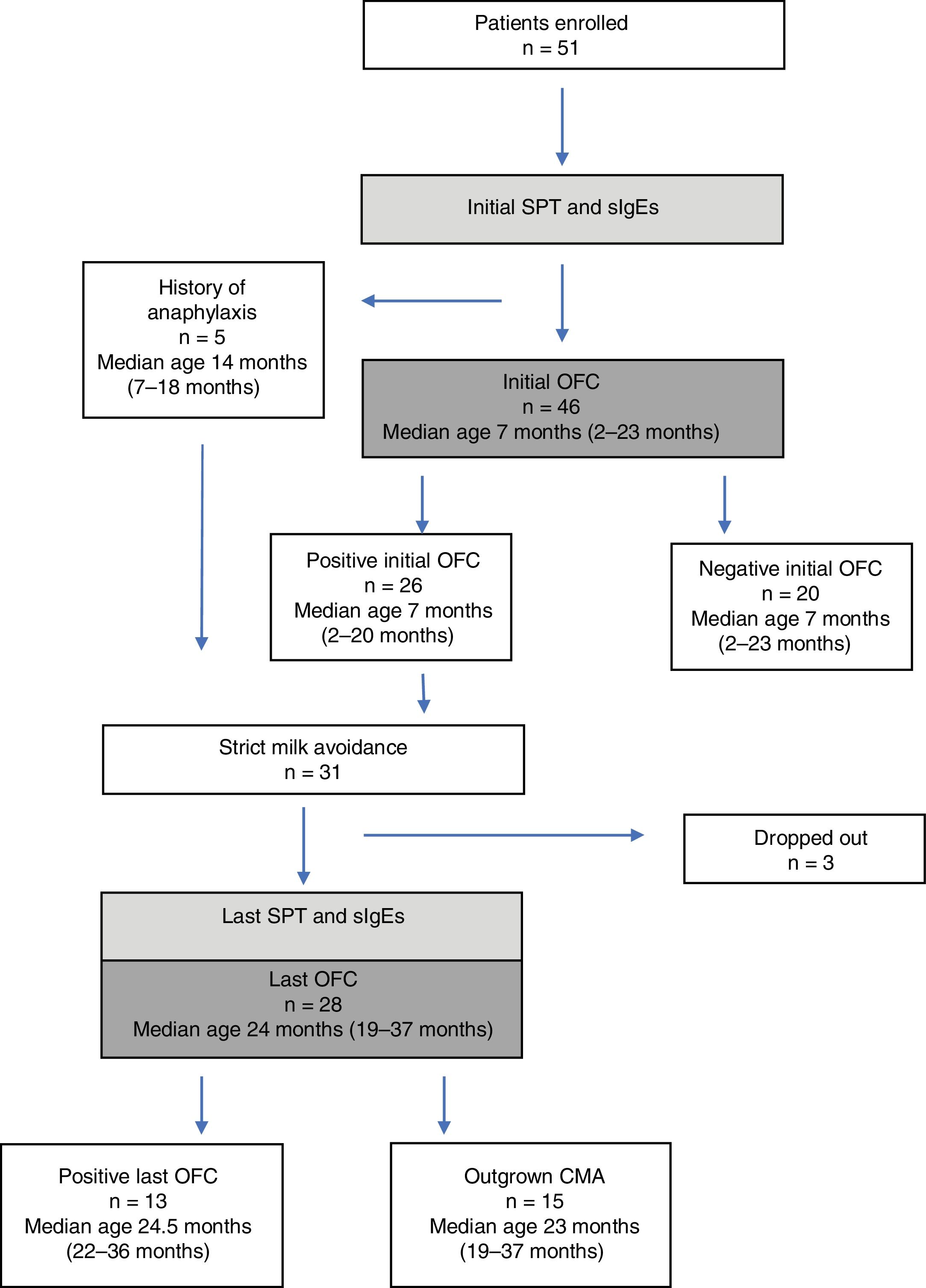

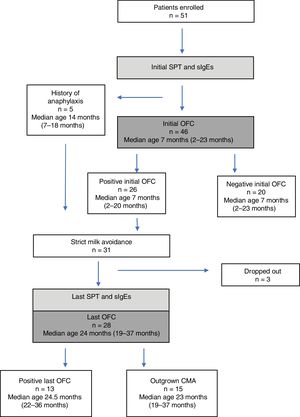

ResultsFifty-one children (median age, 7.5 months; range, 2–23 months) were enrolled. Five had a history of anaphylaxis and 26 of 48 children with a positive initial challenge underwent milk elimination. The last OFC was performed in 28 children of whom 13 reacted to milk. The initial SPT responses to CE and FM and milk sIgE levels of the patients with persistent CMA were higher at diagnosis, with ODPfo of 7mm, 9mm, and 10.5kU/L, respectively; these values remained higher with ODPfo of 4mm, 11mm, and 10.5kU/L at the last OFC.

ConclusionHigher initial SPTs for FM and CE and higher initial sIgE levels for cow's milk proteins are associated with a reduced likelihood of outgrowth. Initial milk sIgE level <10.5kU/L and initial SPT for fresh milk <9mm are related to the acquisition of tolerance in the follow-up period.

Cow's milk allergy (CMA) is the most common food allergy in childhood, affecting about 1.9–4.9% of children worldwide, with 2.27–2.5% occurring in the first two years of life.1 Immunoglobulin E (IgE)-mediated allergy to milk is usually outgrown gradually throughout childhood.1 In practice, skin prick tests (SPT) and specific IgE (sIgE) levels are obtained periodically during follow-up and guide clinician to evaluate the likelihood of resolution. However, SPTs and sIgE measurements are not sufficient to show resolution of CMA on their own. Oral food challenge (OFC) is often required to monitor the acquisition of tolerance. Because OFCs are time-consuming, expensive, and may result in a severe allergic reaction, cut-off levels of SPT and sIgE which predict the optimal candidates for OFC reliably in the first few years of life would be useful in clinical practice.

Previous studies that aimed to identify cut-offs for sIgE or SPTs were involved primarily in guiding clinical diagnosis.2 Few enrolled children younger than two years,3 or used fresh milk (FM) for SPTs.4,5 Because the decision points of SPTs and sIgE assays defined at the time of diagnosis are not the same as those defined in the follow-up period with the aim of predicting outgrowing allergy, various additional studies have evaluated the predictive value of SPT and sIgE assays for tolerance acquisition according to age.6–8 In addition, some authors attempted to establish the values of parameters obtained at the time of diagnosis that would predict CMA outgrowth; some included an SPT with FM.9,10 In general, it is suggested that the cut-off points for food allergens establishing a clinical pattern are different in different populations, so population-based evaluation is needed before the decision is made.

The aim of the present study on children <2 years of age with IgE-mediated CMA was to evaluate the optimal decision points for outgrowth (ODPfo) with SPTs with FM and CE and sIgE levels for cow's milk, casein, α-lactoalbumin, and β-lactoglobulin to predict persistence of allergy or outgrowth after a period of strict food avoidance.

MethodsStudy groupParticipants were recruited prospectively and consecutively from the Pediatric Allergy Clinics of Kocaeli University Medical Faculty from January 2014 to October 2017. Children between the ages of 2 and 24 months who were referred due to a history of reaction to any types of milk (unheated or heated) and/or formula were included in the study.

A positive clinical history of IgE-mediated milk allergy was defined as skin reactions (urticaria, angioedema, atopic dermatitis flare), digestive symptoms (vomiting, diarrhea), or respiratory symptoms (rhinitis, cough, dyspnea) in the 2h after milk intake. Patients with concomitant serious disease, unstable asthma, and multiple sensitizations other than milk and egg were excluded in order to obtain a more homogenous patient population.

The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Kocaeli University Medical Faculty, and written informed consent was obtained from the parents of the patients.

Study designParticipants underwent OFC. Allergy evaluation with sIgEs (cow's milk, casein, α-lactoalbumin, β-lactoglobulin), SPTs for CE and FM were performed in the week before the milk challenge. Diagnosis of IgE-mediated CMA was based on current international guidelines.1 Milk consumption (unheated and heated milk, formula, yogurt and all products which contain milk) was avoided in milk reactive patients. These patients were followed up clinically at three-month intervals. After an average follow-up period of one year, an OFC and the tests for allergy evaluation (sIgEs, SPTs for CE and FM) were repeated.

Milk challengesChallenges were performed openly under physician supervision in the Kocaeli University Pediatric Allergy Unit. Medications that may interfere with the OFC were discontinued as suggested.11 Milk was strictly eliminated for two weeks prior to the OFC. The patient did not eat for at least 4h before the challenge. Stepwise doses of 0.1, 0.5, 1, 3.0, 10.0, 30.0, 50.0 and 100mL were offered at 15–30-min intervals. The total amount was completed to 240mL (8–10g of milk protein). The challenge area was cleaned between challenges. The patient was re-examined before each dose was administered. In patients with underlying atopic dermatitis, the skin was controlled carefully during the time of challenge. The challenge was terminated and considered to be positive when there were symptoms consistent with an allergic reaction within 2h of the last dose, such as skin reactions (urticaria, angioedema, or atopic dermatitis flare), gastrointestinal (vomiting), or respiratory (rhinoconjunctivitis or bronchospasm) manifestations. Transient (disappearing within a few minutes) and non-recurrent peri-oral erythema was considered to be associated with contact irritation and not a sign of a positive reaction.

In case of a negative OFC, the patient was discharged home after at least 1–2h of observation for the immediate-type reactions, and instructions for regular milk or milk-based formula introduction into the diet was provided. The parents were instructed to contact the office with any post-challenge issues. All patients were seen at first follow-up visit constructed between the seventh and the fifteenth days after challenge in order to be sure that they consumed unheated milk or formula regularly. They were also evaluated clinically for allergic manifestations.

Children with positive laboratory findings did not undergo OFC if they had a history of anaphylaxis within the previous 12 months caused by a clearly identified milk consumption.

Specific IgE testssIgE levels for cow's milk, casein, α-lactoalbumin, β-lactoglobulin were assessed using UniCAP (Phadia UniCAP; Pharmacia Diagnostics, Uppsala, Sweden); the lower limit of detection is 0.35kU/L.

Skin prick test for commercial extracts and fresh foodsSPTs were performed with CE (ALK-Abelló, Horsholm, Denmark), and a negative saline and a positive histamine control. The size of the skin test response was calculated as the mean of the longest diameter and the longest orthogonal measured at 15min. The SPT for FM was performed in the same way using regular milk.

Statistical analysesStatistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS for Windows version 20.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) and MedCalc 14.10.2 (MedCalc Software bvba, Ostend, Belgium). Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests were used to test the normality of data distribution. Continuous variables were expressed as mean±standard deviation, median (25th to 75th percentiles), and categorical variables were expressed as counts (percentages). The relationship between sensitivity and specificity and the optimal decision points for sIgE and SPTs were determined by analysis with the receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Correlation between the SPT diameters for CE and the FM was evaluated with Pearson's correlation coefficient. The Yates and Fisher chi-squared test was used for comparison between groups. The Mann–Whitney non-parametric test was used to compare continuous variables between two groups. A two-sided P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

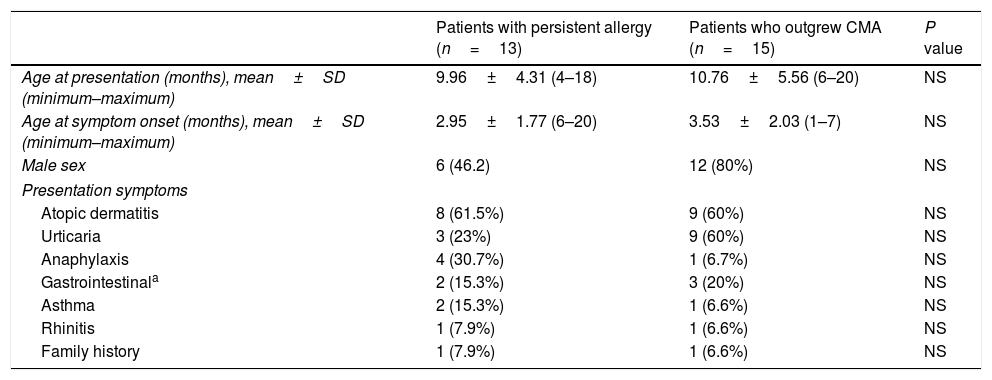

ResultsThe main characteristics of the patients with persistent allergy and the patients who outgrew CMA with regard to age, symptoms, and family history are shown in Table 1. Concomitant allergic diseases were found in all participants.

Characteristics of the patients with persistent allergy and the patients who outgrew cow's milk allergy: age, sex, presentation symptoms, and family history.

| Patients with persistent allergy (n=13) | Patients who outgrew CMA (n=15) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at presentation (months), mean±SD (minimum–maximum) | 9.96±4.31 (4–18) | 10.76±5.56 (6–20) | NS |

| Age at symptom onset (months), mean±SD (minimum–maximum) | 2.95±1.77 (6–20) | 3.53±2.03 (1–7) | NS |

| Male sex | 6 (46.2) | 12 (80%) | NS |

| Presentation symptoms | |||

| Atopic dermatitis | 8 (61.5%) | 9 (60%) | NS |

| Urticaria | 3 (23%) | 9 (60%) | NS |

| Anaphylaxis | 4 (30.7%) | 1 (6.7%) | NS |

| Gastrointestinala | 2 (15.3%) | 3 (20%) | NS |

| Asthma | 2 (15.3%) | 1 (6.6%) | NS |

| Rhinitis | 1 (7.9%) | 1 (6.6%) | NS |

| Family history | 1 (7.9%) | 1 (6.6%) | NS |

SD, standard deviation. Values are number (%) except where indicated otherwise.

Forty-six children (median age, seven months; range, 2–23 months) (58% boys) underwent an initial OFC. Twenty-six initial challenges were assessed as positive. Atopic dermatitis flare within 2h of challenge, urticaria, and both these reactions were observed in 12, 6, and 8 children, respectively. The challenge was not performed on five infants because of a history of a life-threatening anaphylactic reaction to milk, contraindicating a food challenge. These five patients were judged to have positive initial OFC (Fig. 1).

SPT and sIgE characteristics during the initial challengeThe mean initial SPT diameters for CE and FM and the mean initial sIgE levels for cow's milk and three main cow's milk proteins were significantly higher in the reactive patients (P<0.001) (data not shown). The correlation between the diameters for CE and FM in the reactive patients was evaluated and Pearson correlation coefficient was found to be 0.817 (P<0.001).

Last challengeThe average follow-up time was 15 months. Three patients were lost to follow-up. The last challenge test was performed on the remaining 28 children. Thirteen (46%) reacted to milk. Atopic dermatitis flare within 2h, urticaria, and mild anaphylaxis developed in eight, three, and four children, respectively.

Fifteen children (53%), including one of five patients with a history of anaphylaxis, had outgrown their allergy. The mean ages of patients with persistent allergy and those who outgrew their allergy were 27.1±9 months and 24.5±7.8 months, respectively (P>0.5). The patients with persistent allergy were referred at the mean age of 10.0±4.3 months, similar to the patients who outgrew CMA (10.2±5.2 months) (P>0.5). The initial allergic manifestations of those who had a positive and negative OFC occurred when they were 3.2±1.9 and 3.8±2.2 months, respectively (P>0.5).

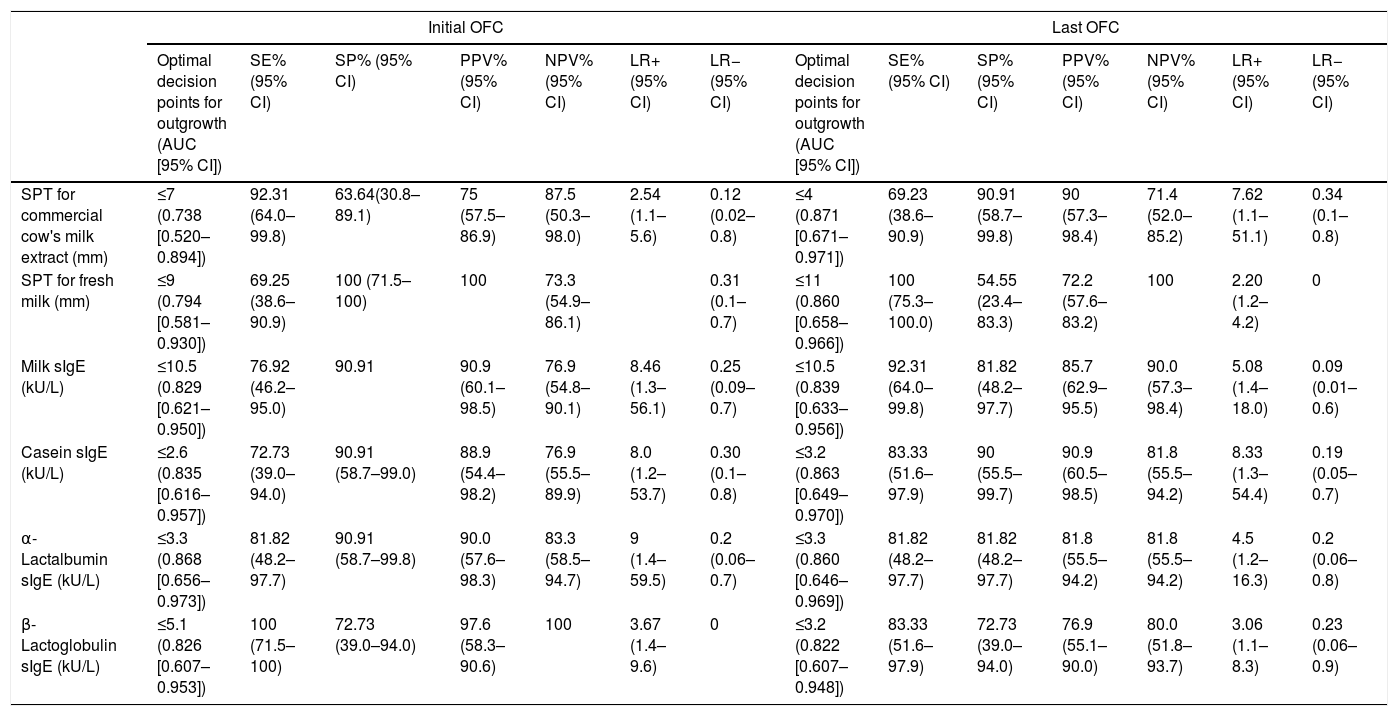

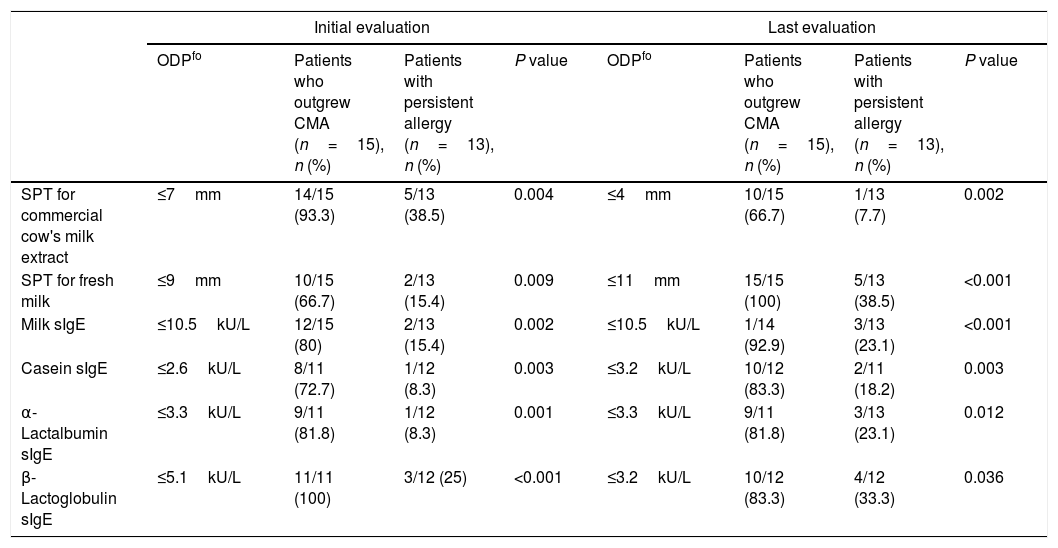

Performance of SPT and sIgE obtained during the initial challenge in predicting outgrowing CMAThe performance of the initial SPT and sIgE assays to predict outgrowing allergy in the follow-up period compared with the last OFC as gold standard is shown in Table 2. Analysis of the ROC curve showed that ODPfo of SPTs for CE and FM were 7mm and 9mm, with positive predictive values (PPVs) of 75% and 100%, respectively. The levels of milk (PPV, 90.9%), casein, α-lactalbumin, and β-lactoglobulin sIgE at diagnosis were 10.5, 2.6, 3.3 and 5.1kU/L as ODPfos to show allergy persistence or outgrowth in the follow-up period, respectively.

Performance of SPT and sIgE obtained during the initial and last OFC in predicting outgrowth.

| Initial OFC | Last OFC | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Optimal decision points for outgrowth (AUC [95% CI]) | SE% (95% CI) | SP% (95% CI) | PPV% (95% CI) | NPV% (95% CI) | LR+ (95% CI) | LR− (95% CI) | Optimal decision points for outgrowth (AUC [95% CI]) | SE% (95% CI) | SP% (95% CI) | PPV% (95% CI) | NPV% (95% CI) | LR+ (95% CI) | LR− (95% CI) | |

| SPT for commercial cow's milk extract (mm) | ≤7 (0.738 [0.520–0.894]) | 92.31 (64.0–99.8) | 63.64(30.8–89.1) | 75 (57.5–86.9) | 87.5 (50.3–98.0) | 2.54 (1.1–5.6) | 0.12 (0.02–0.8) | ≤4 (0.871 [0.671–0.971]) | 69.23 (38.6–90.9) | 90.91 (58.7–99.8) | 90 (57.3–98.4) | 71.4 (52.0–85.2) | 7.62 (1.1–51.1) | 0.34 (0.1–0.8) |

| SPT for fresh milk (mm) | ≤9 (0.794 [0.581–0.930]) | 69.25 (38.6–90.9) | 100 (71.5–100) | 100 | 73.3 (54.9–86.1) | 0.31 (0.1–0.7) | ≤11 (0.860 [0.658–0.966]) | 100 (75.3–100.0) | 54.55 (23.4–83.3) | 72.2 (57.6–83.2) | 100 | 2.20 (1.2–4.2) | 0 | |

| Milk sIgE (kU/L) | ≤10.5 (0.829 [0.621–0.950]) | 76.92 (46.2–95.0) | 90.91 | 90.9 (60.1–98.5) | 76.9 (54.8–90.1) | 8.46 (1.3–56.1) | 0.25 (0.09–0.7) | ≤10.5 (0.839 [0.633–0.956]) | 92.31 (64.0–99.8) | 81.82 (48.2–97.7) | 85.7 (62.9–95.5) | 90.0 (57.3–98.4) | 5.08 (1.4–18.0) | 0.09 (0.01–0.6) |

| Casein sIgE (kU/L) | ≤2.6 (0.835 [0.616–0.957]) | 72.73 (39.0–94.0) | 90.91 (58.7–99.0) | 88.9 (54.4–98.2) | 76.9 (55.5–89.9) | 8.0 (1.2–53.7) | 0.30 (0.1–0.8) | ≤3.2 (0.863 [0.649–0.970]) | 83.33 (51.6–97.9) | 90 (55.5–99.7) | 90.9 (60.5–98.5) | 81.8 (55.5–94.2) | 8.33 (1.3–54.4) | 0.19 (0.05–0.7) |

| α-Lactalbumin sIgE (kU/L) | ≤3.3 (0.868 [0.656–0.973]) | 81.82 (48.2–97.7) | 90.91 (58.7–99.8) | 90.0 (57.6–98.3) | 83.3 (58.5–94.7) | 9 (1.4–59.5) | 0.2 (0.06–0.7) | ≤3.3 (0.860 [0.646–0.969]) | 81.82 (48.2–97.7) | 81.82 (48.2–97.7) | 81.8 (55.5–94.2) | 81.8 (55.5–94.2) | 4.5 (1.2–16.3) | 0.2 (0.06–0.8) |

| β-Lactoglobulin sIgE (kU/L) | ≤5.1 (0.826 [0.607–0.953]) | 100 (71.5–100) | 72.73 (39.0–94.0) | 97.6 (58.3–90.6) | 100 | 3.67 (1.4–9.6) | 0 | ≤3.2 (0.822 [0.607–0.948]) | 83.33 (51.6–97.9) | 72.73 (39.0–94.0) | 76.9 (55.1–90.0) | 80.0 (51.8–93.7) | 3.06 (1.1–8.3) | 0.23 (0.06–0.9) |

SPT: skin prick test; sIgE: specific immunoglobulin E; OFC: oral food challenge; SE: sensitivity; SP: specificity; PPV: positive predictive value; NPV: negative predictive value; LR+: positive likelihood ratio; LR−: negative likelihood ratio; AUC: area under the curve; CI: confidence interval.

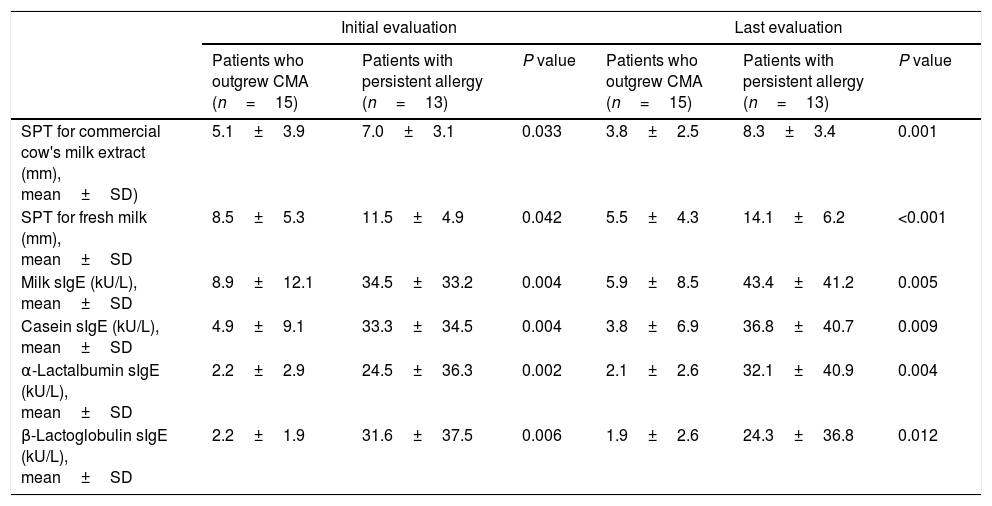

The proportions of patients with levels above these ODPfo values were higher in the persistent group than in those who outgrew CMA. Diameters of the initial SPTs for CE and FM and milk sIgE levels were below these ODPfo values in 93.3%, 66.7%, and 80% of the patients who outgrew CMA during the last evaluation, respectively (Table 3). Initial SPT and sIgE parameters were higher at diagnosis and remained higher in the follow-up period in the patients with persistent allergy than in those who outgrew CMA (Table 4).

Distribution of patients who underwent the last oral food challenge according to the ODPfo from SPTs and sIgE levels obtained during the initial and last evaluation to predict persistence or outgrowth.

| Initial evaluation | Last evaluation | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ODPfo | Patients who outgrew CMA (n=15), n (%) | Patients with persistent allergy (n=13), n (%) | P value | ODPfo | Patients who outgrew CMA (n=15), n (%) | Patients with persistent allergy (n=13), n (%) | P value | |

| SPT for commercial cow's milk extract | ≤7mm | 14/15 (93.3) | 5/13 (38.5) | 0.004 | ≤4mm | 10/15 (66.7) | 1/13 (7.7) | 0.002 |

| SPT for fresh milk | ≤9mm | 10/15 (66.7) | 2/13 (15.4) | 0.009 | ≤11mm | 15/15 (100) | 5/13 (38.5) | <0.001 |

| Milk sIgE | ≤10.5kU/L | 12/15 (80) | 2/13 (15.4) | 0.002 | ≤10.5kU/L | 1/14 (92.9) | 3/13 (23.1) | <0.001 |

| Casein sIgE | ≤2.6kU/L | 8/11 (72.7) | 1/12 (8.3) | 0.003 | ≤3.2kU/L | 10/12 (83.3) | 2/11 (18.2) | 0.003 |

| α-Lactalbumin sIgE | ≤3.3kU/L | 9/11 (81.8) | 1/12 (8.3) | 0.001 | ≤3.3kU/L | 9/11 (81.8) | 3/13 (23.1) | 0.012 |

| β-Lactoglobulin sIgE | ≤5.1kU/L | 11/11 (100) | 3/12 (25) | <0.001 | ≤3.2kU/L | 10/12 (83.3) | 4/12 (33.3) | 0.036 |

ODPfo: optimal decision point for outgrowth; CMA: cow's milk allergy; SPT: skin prick test; sIgE: specific immunoglobulin E.

Initial and last SPT and sIgE characteristics of the patients who undergone the last OFC.

| Initial evaluation | Last evaluation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients who outgrew CMA (n=15) | Patients with persistent allergy (n=13) | P value | Patients who outgrew CMA (n=15) | Patients with persistent allergy (n=13) | P value | |

| SPT for commercial cow's milk extract (mm), mean±SD) | 5.1±3.9 | 7.0±3.1 | 0.033 | 3.8±2.5 | 8.3±3.4 | 0.001 |

| SPT for fresh milk (mm), mean±SD | 8.5±5.3 | 11.5±4.9 | 0.042 | 5.5±4.3 | 14.1±6.2 | <0.001 |

| Milk sIgE (kU/L), mean±SD | 8.9±12.1 | 34.5±33.2 | 0.004 | 5.9±8.5 | 43.4±41.2 | 0.005 |

| Casein sIgE (kU/L), mean±SD | 4.9±9.1 | 33.3±34.5 | 0.004 | 3.8±6.9 | 36.8±40.7 | 0.009 |

| α-Lactalbumin sIgE (kU/L), mean±SD | 2.2±2.9 | 24.5±36.3 | 0.002 | 2.1±2.6 | 32.1±40.9 | 0.004 |

| β-Lactoglobulin sIgE (kU/L), mean±SD | 2.2±1.9 | 31.6±37.5 | 0.006 | 1.9±2.6 | 24.3±36.8 | 0.012 |

SPT: skin prick test; sIgE: specific immunoglobulin E; OFC: oral food challenge; CMA: cow's milk allergy; SD: standard deviation.

The performance of the last SPTs and sIgE assays, indicating CMA persistence or outgrowth, compared with the last OFC is shown in Table 3. Analysis of the ROC curve showed that ODPfo values for SPTs for CE and FM were 4mm and 11mm, with PPVs of 90% and 72.2%, respectively. The ODPfo values for the last assays of milk, casein, α-lactalbumin and β-lactoglobulin sIgEs were 10.5 (PPV, 85.7%), 3.2, 3.3, and 3.2kU/L, respectively (Table 2).

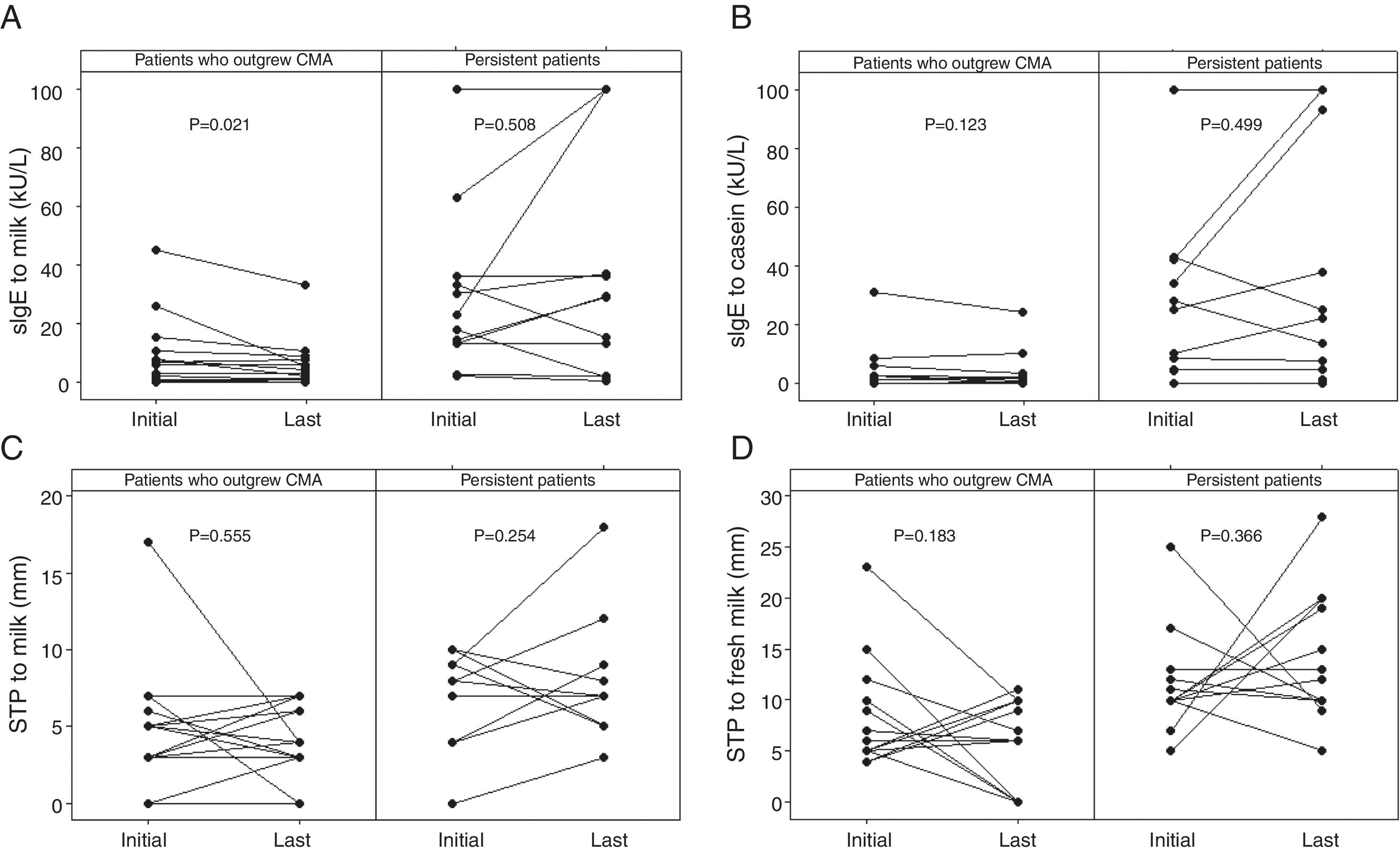

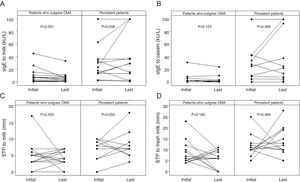

Diameters of the last SPTs for CE and FM and milk sIgE levels were below the ODPfo values in 66.7%, 100%, and 92.9% of the patients who outgrew CMA. The proportions of patients with the last SPTs and sIgE levels below these ODPfo values were higher among patients who outgrew CMA than those with persistent allergy (Table 3). The initial parameters of the patients with persistent allergy were higher at diagnosis and remained higher in the follow-up period (Table 4 and Fig. 2).

The initial and the last levels of sIgE for milk (kU/L) (A) and casein (kU/L) (B), SPT for milk (mm) (C), and fresh milk (mm) (D) in the patients who outgrew CMA and in those with persistent allergy. The initial parameters of the patients with persistent allergy were higher at diagnosis and remained higher in the follow-up period. Wilcoxon signed ranks test was used. SPT: skin prick test; sIgE: specific immunoglobulin E; CMA: cow's milk allergy.

We investigated the optimal criteria for SPTs with CE and FM and sIgE levels for cow's milk and its three major proteins to predict persistence or outgrowing allergy in children <2 years with IgE-mediated CMA after a period of strict food avoidance. In assessing the performance of the initial SPTs for CE and FM, and initial milk sIgE assays in predicting outgrowing allergy compared with the last OFC as the gold standard, analysis of the ROC curve showed that the ODPfo values were 7mm, 9mm, and 10.5kU/L with PPVs of 75%, 100%, and 90.9%, respectively. These initial parameters were higher at diagnosis and remained higher in the follow-up period in patients with persistent allergy than in those who outgrew CMA. These parameters gave ODPfo values of 4mm, 11mm, and 10.5kU/L with PPVs of 90%, 72.2%, and 85.7%, respectively, to indicate outgrowing allergy during the last OFC performed after an average follow-up time of 15 months.

It is known that the potency of the allergen extracts used in SPTs affects the results, and commercial food extracts may lose their antigenic properties. Fresh food extracts were reported to be more effective in detecting sensitization than commercial extracts.12–14 Previous studies have primarily used SPTs for FM to guide clinical diagnosis.4,5,15–18

Among the studies that aimed to assess the role of initial parameters on outgrowth, some evaluated the initial SPT wheal size,19 whereas others evaluated sIgE levels,8 or both.9,10 However, few studies evaluated the role of the initial SPT diameters9 or the course of tolerance acquisition with FM.20 Vanto et al. showed that a wheal size with an SPT for cow's milk-based formula <5mm at diagnosis correctly identified 83% who developed tolerance at four years.9 In a cohort study of 112 infants, an FM wheal diameter increment of 1mm was found to be a predictor of persistence.20 We found that the initial SPT diameters with FM were significantly larger in patients who remained persistent (11.5mm vs 8.5mm, P=0.042). Furthermore, the diameters with FM in patients with persistent allergy increased in the follow-up period and reached higher values (14mm), whereas a decline in diameters was observed in the children who outgrew CMA (5.5mm). We showed that the ODPfo value for the initial SPT for FM was 9mm with a PPV of 100% and a negative predictive value (NPV) of 73%. Eighty-four percent of the patients who had a SPT diameter for FM ≥9mm during the initial challenge remained persistent.

In addition to studies involving FM, many investigators have demonstrated that commercial SPT wheal size could be useful in discriminating persistence and outgrowth.21–23 It was shown that the greater the SPT wheal size, the higher the likelihood that the patient reacts during an OFC.22 Kido et al.24 found that the patients with CMA were likely to outgrow CMA when their wheal diameter for CE decreased to 8mm. In another study evaluating tolerance through an SPT with CE, it was found that a decrease of more than 50% in diameter could indicate the moment to perform an OFC, helping to detect tolerance in CMA.25 We observed that outgrowing allergy was least likely in children with a higher initial diameter and in children with higher levels remaining after an average follow-up time of 15 months. Ninety-three percent of our patients who had an SPT diameter for CE ≤7mm during the initial challenge outgrew CMA. No patients with a diameter >8mm outgrew CMA. We also found that an SPT diameter for CE ≥4mm predicted clinical reactivity in the follow-up period, with 90% PPV, 90% specificity, and 71.4% NPV.

Considering the concentrations of sIgE for cow's milk and its three major proteins, lower concentrations initially, and levels decreasing significantly with time were reported in those patients who lost their clinical sensitivity.26,27 It was also shown that milk sIgE concentration in the first year of life can serve as a predictor of the persistence of CMA.28 The authors found that 70% of children who had resolved their CMA at three years old had a milk sIgE level lower than 3IU/mL before the age of one year. Vanto et al. showed that <2kU/L at the onset of CMA correctly identified 82% who developed tolerance at four years.9 In a cohort study, Wood et al.10 reported that more than 70% patients with baseline milk sIgE levels <2kUA/L had resolved milk allergy, whereas among those with levels ≥10kU/L, only 23% had resolved. We found that an initial milk sIgE level of 10.5kU/L predicted clinical reactivity at age two years with 90% PPV, 90% specificity, and 76% NPV. We found that 73.3% of our patients with initial levels <10.5kU/L outgrew CMA, whereas only 15.4% with initial levels >10.5kU/L outgrew CMA.

Changing allergometric values according to age has been the focus of some studies. It was found that the sIgE levels that predicted reactivity (PPV ≥90%) increased as the age of the infants increased: 1.5, 6, and 14kUA/L for milk and 0.6, 3 and 5kUA/L for casein, in the age range 13–18 months, 19–24 months, and in the third year, respectively.6 Martorell et al.7 reported that the ODPs of milk and casein sIgE levels were 2.58 and 0.97kU/L in children aged 12 months, 2.5 and 1.22kU/L in children aged 18 months, and 2.7 and 3kU/L in children aged 24 months. In another study, the probability curves for milk sIgE with 95% decision points were 2.8, 11.1, 11.7, and 13.7kU/L for <1, <2, <4, and <6 years, respectively.8 In all age groups, the cut-off value for milk sIgE was 11kU/L (95% PPV). We found the ODPfo value for milk sIgE was 10.5kU/L in both age groups in which the initial and the last evaluation were performed. The ODPfo values for casein sIgE were 2.6 and 3.2kU/L for <1 years and at the end of two years, respectively.

Our study offers data predicting outgrowth of CMA in the follow-up period in children <2 years of age with regard to SPT with FM. The small sample size is a limitation of our study. It is reported that open challenges do not seem to cause bias in the first years of life, therefore we used open challenges instead of double-blind, placebo-controlled food challenges.4

ConclusionHigher initial SPTs for FM and CE and higher initial sIgE levels for cow's milk and its three major proteins are associated with a reduced likelihood of outgrowth. Initial milk sIgE level ≤10.5kU/L and initial SPT for fresh milk ≤9mm are related to the acquisition of tolerance in the follow-up period with over 90% PPV. We consider an SPT for FM and sIgE levels for three major milk proteins can be used to monitor outgrowth in children <2 years old with IgE-mediated CMA, alongside an SPT for CE and milk sIgE levels.

FundingUnderlying research reported in the article was not funded.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.