Omalizumab is useful as an add-on treatment in patients unresponsive to high doses of second-generation antihistamines. This study aimed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of omalizumab treatment in adolescents with refractory chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU).

MethodsCSU patients aged 12–18 years old with the diagnosis of symptomatic CSU and unresponsive to classical treatment were included in the study. All patients had an urticaria-activity-score (UAS7) of ≥16 or and were treated with 300mg omalizumab every four weeks. The degree of response was classified into complete, partial and non-responders due to UAS7.

ResultsA total of 29 patients were evaluated. The median age and symptom onset age of the patients was 15.2 (IQR, 12.8–16.5) years and 14.0 (IQR, 11.8–15.9) years, respectively. The median duration of urticaria was eight (IQR, 4–24) months at admission. Eleven (37.9%) patients had angioedema and ten (34.5%) patients had concomitant allergic diseases. The median age at the beginning of treatment with omalizumab was 15.4 (IQR, 12.9–16.9) years. The median symptom duration was 12 (IQR, 6.5–27.5) months before the omalizumab treatment. Twenty-eight (96.5%) of the patients (89.6% complete, 6.9% partial) achieved response; however, one patient was a non-responder (3.5%). The adverse effect was observed in one (3.4%) patient as angioedema after the third dose. Twenty-three patients were followed up for a median of 18 (IQR, 13–27) months. Relapse was observed in three (13%) patients.

ConclusionsOmalizumab is considered as an effective and safe treatment for CSU in adolescents. Relapses mostly occur within the first year after the cessation of treatment.

Chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU) is a disease characterized by itchy hives and/or angioedema that occur daily or almost daily for at least six weeks without any external stimulus.1 Inducible urticaria and urticarial vasculitis form the other types of chronic urticaria (CU).2 Chronic urticaria in children may affect up to 3% of the pediatric population.3 According to current guidelines, the treatment for chronic urticaria involves H1 antihistamines as the first-line, which can be increased up to fourfold the licensed dosage. However, one-third of adults and more than 10% of children do not respond to high dose H1 antihistamines and require third-line treatment such as omalizumab, cyclosporine, and montelukast.4,5 Omalizumab is a recombinant humanized monoclonal anti-IgE antibody that binds to free IgE and indirectly downregulates FcɛRI receptor expression on mast cells and basophils.6 Omalizumab was approved by the FDA in March 2014 for CSU in adults and adolescents 12 years of age and older in cases of antihistamine refractoriness.7 A multicenter study from Italy included 322 patients with refractory CSU aged 15–83 years showed that omalizumab is a well-tolerated and effective therapy for this wide age range population.8

Even though the current literature on the treatment of CSU with omalizumab is rapidly increasing, information about the efficacy and safety of omalizumab treatment in children with CSU is limited. Large pivotal phase III trials have demonstrated a good safety and efficacy profile.9–11 A recent systematic literature review of omalizumab treatment of children with CSU less than 12 years of age suggested that omalizumab could be a safe treatment option in this age group.12 There is also a published information gap on the use of omalizumab in the subgroup of patients from 12 to younger than 18 years old with CSU. A study that analyzed a total of 39 adolescents with CSU in three phase III studies reported potential differences in baseline demographic and clinical characteristics between adult and adolescent patients.13 Considering these limited data in children, this study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of omalizumab in adolescents with recalcitrant chronic spontaneous urticaria.

MethodsThis study was conducted at Hacettepe University School of Medicine, Department of Pediatric Allergy, between January 2015 and August 2018 and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Hacettepe University. Informed written consent was obtained from all patients and parents.

Chronic urticaria was the presence of recurrent urticaria, angioedema, or both, for six weeks or longer. Patients without a clinical response who were treated with second-generation antihistamines at a four-fold increased dose were defined as refractory CSU.14 Twenty-nine refractory CSU patients from 12 to 18 years old with a diagnosis of symptomatic CSU were included in the study population. The study had both retrospective and prospective aspects. First, the medical reports of CSU patients were evaluated retrospectively. Then the clinical status of each patient was evaluated firstly by a telephone visit and then by hospital visits. Urticaria activity score of 7 (UAS7) was used to evaluate disease activity. Itching severity and urticarial plaque number were graded and the sum of seven days of UAS gave the UAS7.1 All the patients had an UAS7 of 16 or greater. Patients were treated with 300mg omalizumab subcutaneously once every four weeks. The treatment continued until the patient had no symptoms for three months. If this time was less than six months, the total duration of the treatment was completed to six months. The patients were evaluated at each visit for the effectiveness of the therapy.

The degree of response was classified into complete responders (UAS7=0), partial responders (UAS7≤6 but not 0) and non-responders (UAS7>6).15 Relapse was considered to be the reappearance of CSU symptoms after the end of the omalizumab treatment.

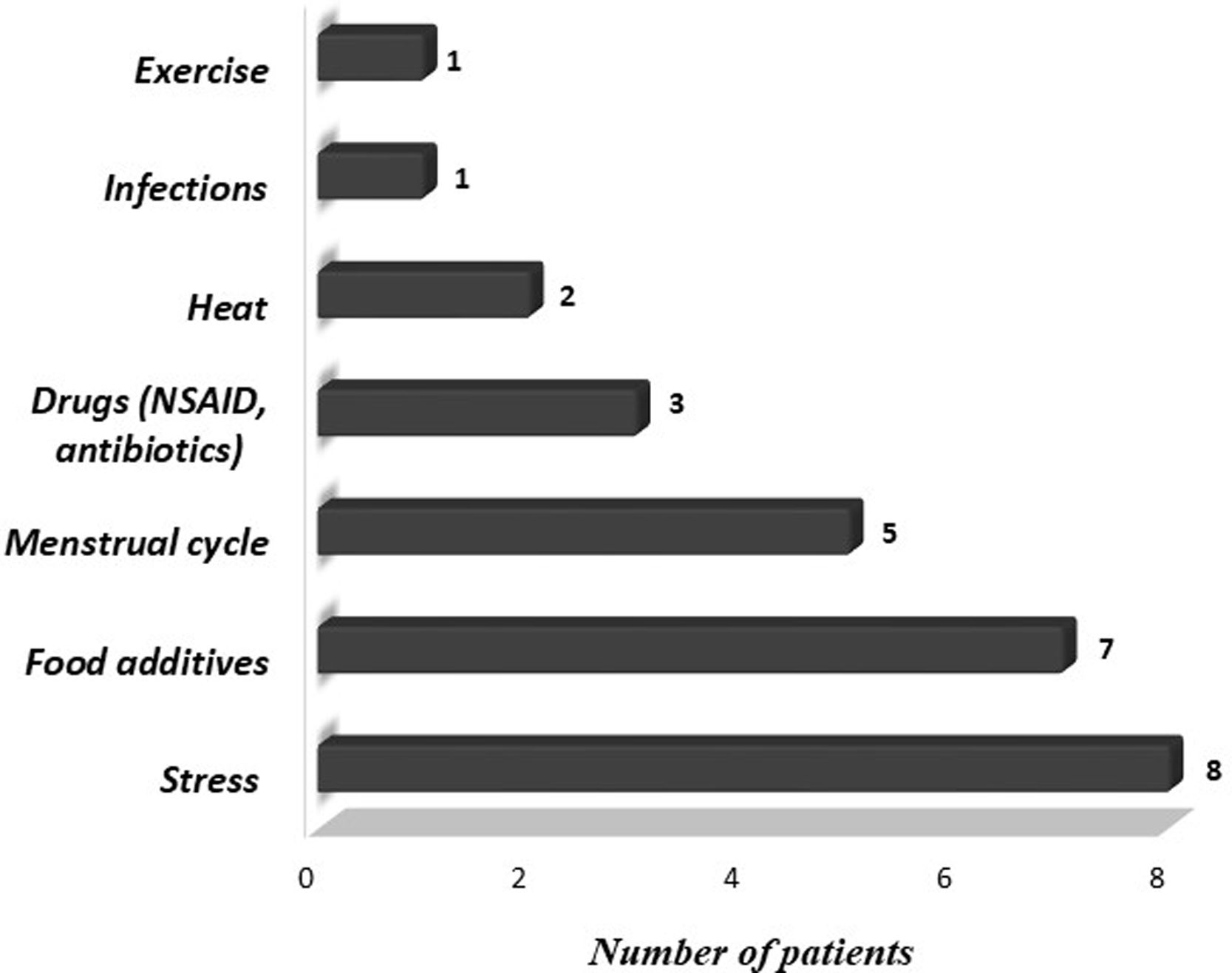

We also evaluated demographic and clinical features of patients, including gender, age at onset, frequency and duration of symptoms, presence of angioedema, concomitant symptoms other than urticaria or angioedema, personal and familial history of allergic diseases, chronic diseases and laboratory findings. Triggering factors that increase symptoms such as cold, heat, sunlight, exercise, stress, infection, food additives, menstrual cycle, and drugs were questioned. Medications (H1 receptor antagonists, H2 receptor antagonists, oral corticosteroids, leukotriene receptor antagonists (LTRA), immunosuppressants) administered before omalizumab treatment, treatments administered concurrently with omalizumab and side effects during omalizumab treatment were recorded.

Complete blood cell count, eosinophil percentage, total immunoglobulin E (IgE), specific IgE levels, C-reactive protein level, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C3 and C4 levels, thyroid hormones, thyroid autoantibodies, antinuclear antibody, anti-double-stranded DNA antibody, urine analysis and stool examination for parasites were reviewed from the database.16,17 The normal limits of the laboratory results were evaluated as follows: thyroid-stimulating hormone: 0.38–5.33μIU/mL; thyroxine: 7.86–14.41pmol/L; sedimentation rate: 0–20mm/h; C-reactive protein: 0–0.8mg/dl; C3: 79–152mg/dl; C4: 16–38mg/dl.

The data were analyzed with SPSS statistical software, version 20.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). The proportions in different groups were compared by using the Pearson χ2 test or the Fisher exact test. All numeric variables were non-normally distributed and compared with Mann–Whitney U or Kruskal–Wallis tests, when appropriate; the results were given as median and interquartile ranges (IQR). A p-value of 0.05 indicated a statistically significant result.18

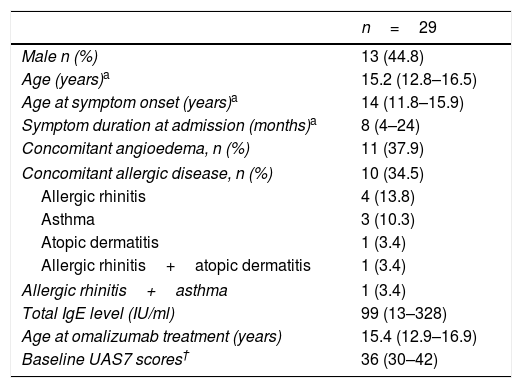

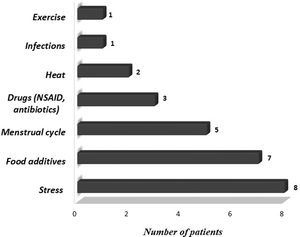

ResultsA total of 29 patients who met the study criteria were evaluated. The patients were predominantly females (n=16; 55%). The median age and symptom onset age of the patients were 15.2 years (IQR, 12.8–16.5 years) and 14.0 years (IQR, 11.8–15.9 years), respectively. The median duration of urticaria before omalizumab treatment was eight months (IQR, 4–24 months). Eleven (37.9%) patients had angioedema and 10 (34.5%) patients had concomitant allergic diseases. A family history of allergic diseases was present in seven (24.1%) patients. The characteristics of the patients are summarized in Table 1. Triggering factors that increased the symptoms of patients are given in Fig. 1.

Characteristics of the study population.

| n=29 | |

|---|---|

| Male n (%) | 13 (44.8) |

| Age (years)a | 15.2 (12.8–16.5) |

| Age at symptom onset (years)a | 14 (11.8–15.9) |

| Symptom duration at admission (months)a | 8 (4–24) |

| Concomitant angioedema, n (%) | 11 (37.9) |

| Concomitant allergic disease, n (%) | 10 (34.5) |

| Allergic rhinitis | 4 (13.8) |

| Asthma | 3 (10.3) |

| Atopic dermatitis | 1 (3.4) |

| Allergic rhinitis+atopic dermatitis | 1 (3.4) |

| Allergic rhinitis+asthma | 1 (3.4) |

| Total IgE level (IU/ml) | 99 (13–328) |

| Age at omalizumab treatment (years) | 15.4 (12.9–16.9) |

| Baseline UAS7 scores† | 36 (30–42) |

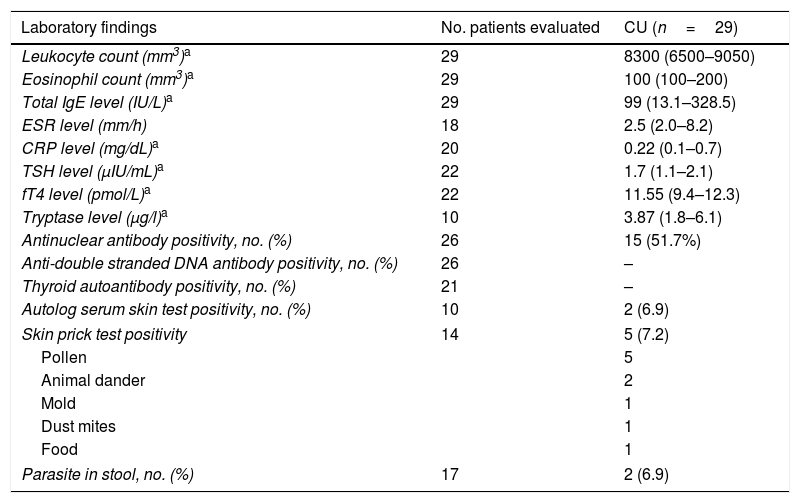

High antinuclear antibody titers (>1/160) were found in 15/26 (57.6%) patients but none of them were diagnosed as having the rheumatologic disease during the study period. Skin prick tests (SPT) and autolog serum skin testing were performed on only 10 patients due to the use of antihistamines. Autolog serum skin testing was positive in 2/10 (20%) patients and SPT was positive in 5/10 (50%) patients. The leukocyte and eosinophil counts, C3 and C4 levels were within normal limits. All the patients had normal thyroid function tests and negative thyroid autoantibody results. Stool parasite examination was positive in 2/17 (11.7%) patients and Blastocystis hominis eggs were detected (Table 2).

Laboratory findings of children with CSU.

| Laboratory findings | No. patients evaluated | CU (n=29) |

|---|---|---|

| Leukocyte count (mm3)a | 29 | 8300 (6500–9050) |

| Eosinophil count (mm3)a | 29 | 100 (100–200) |

| Total IgE level (IU/L)a | 29 | 99 (13.1–328.5) |

| ESR level (mm/h) | 18 | 2.5 (2.0–8.2) |

| CRP level (mg/dL)a | 20 | 0.22 (0.1–0.7) |

| TSH level (μIU/mL)a | 22 | 1.7 (1.1–2.1) |

| fT4 level (pmol/L)a | 22 | 11.55 (9.4–12.3) |

| Tryptase level (μg/l)a | 10 | 3.87 (1.8–6.1) |

| Antinuclear antibody positivity, no. (%) | 26 | 15 (51.7%) |

| Anti-double stranded DNA antibody positivity, no. (%) | 26 | – |

| Thyroid autoantibody positivity, no. (%) | 21 | – |

| Autolog serum skin test positivity, no. (%) | 10 | 2 (6.9) |

| Skin prick test positivity | 14 | 5 (7.2) |

| Pollen | 5 | |

| Animal dander | 2 | |

| Mold | 1 | |

| Dust mites | 1 | |

| Food | 1 | |

| Parasite in stool, no. (%) | 17 | 2 (6.9) |

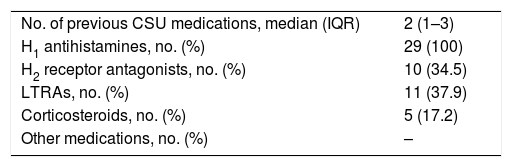

Medications used before the start of omalizumab treatment were H1 antihistamines (100%), H2 receptor antagonists (34.5%), montelukast (37.9%) and oral corticosteroids (17.2%) (Table 3).

Treatments of CSU patients before the start of omalizumab.

| No. of previous CSU medications, median (IQR) | 2 (1–3) |

| H1 antihistamines, no. (%) | 29 (100) |

| H2 receptor antagonists, no. (%) | 10 (34.5) |

| LTRAs, no. (%) | 11 (37.9) |

| Corticosteroids, no. (%) | 5 (17.2) |

| Other medications, no. (%) | – |

Abbreviations. CSU: chronic spontaneous urticaria; H1: histamine1; H2: histamine2; LTRA: leukotriene receptor antagonist.

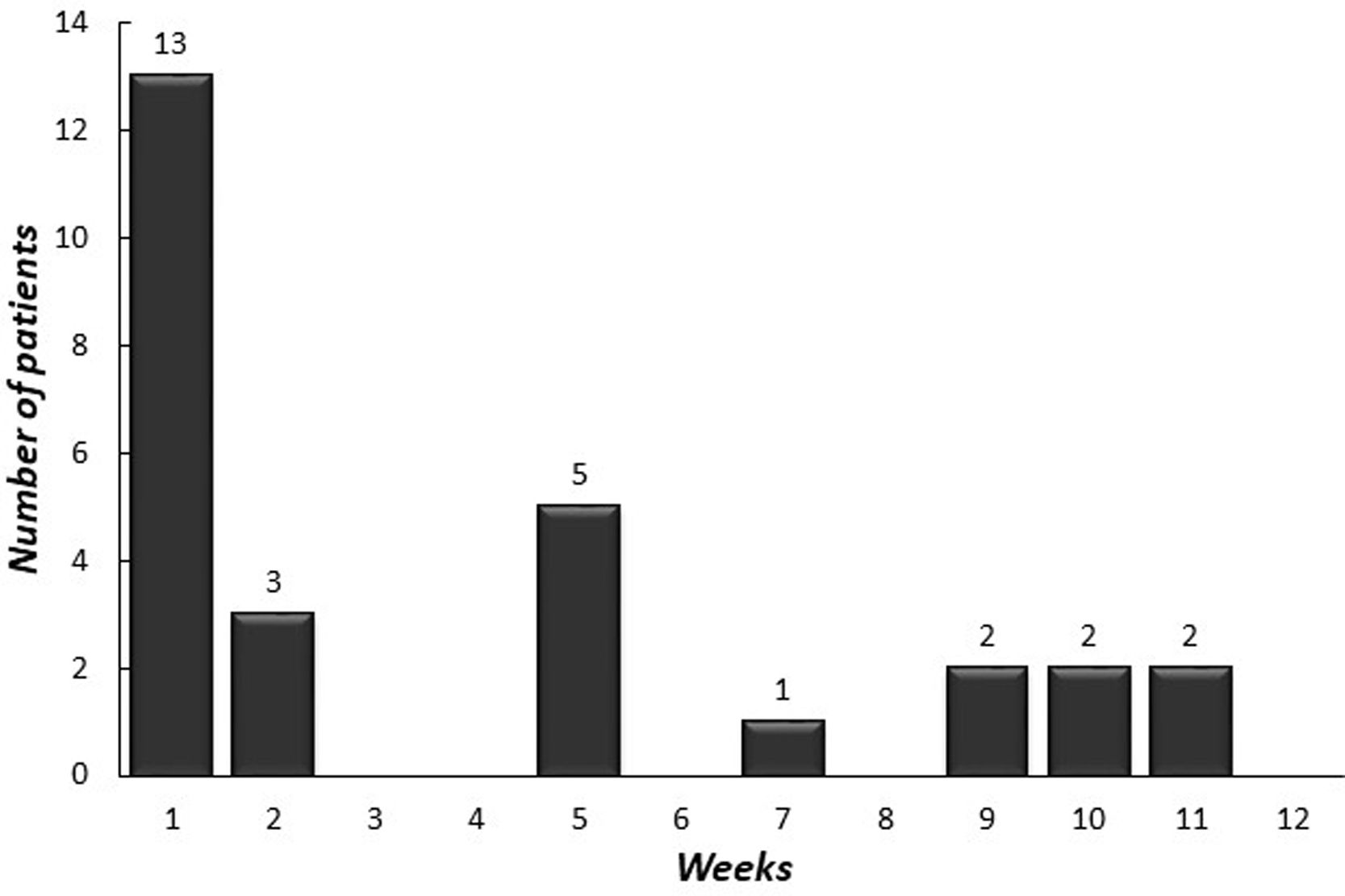

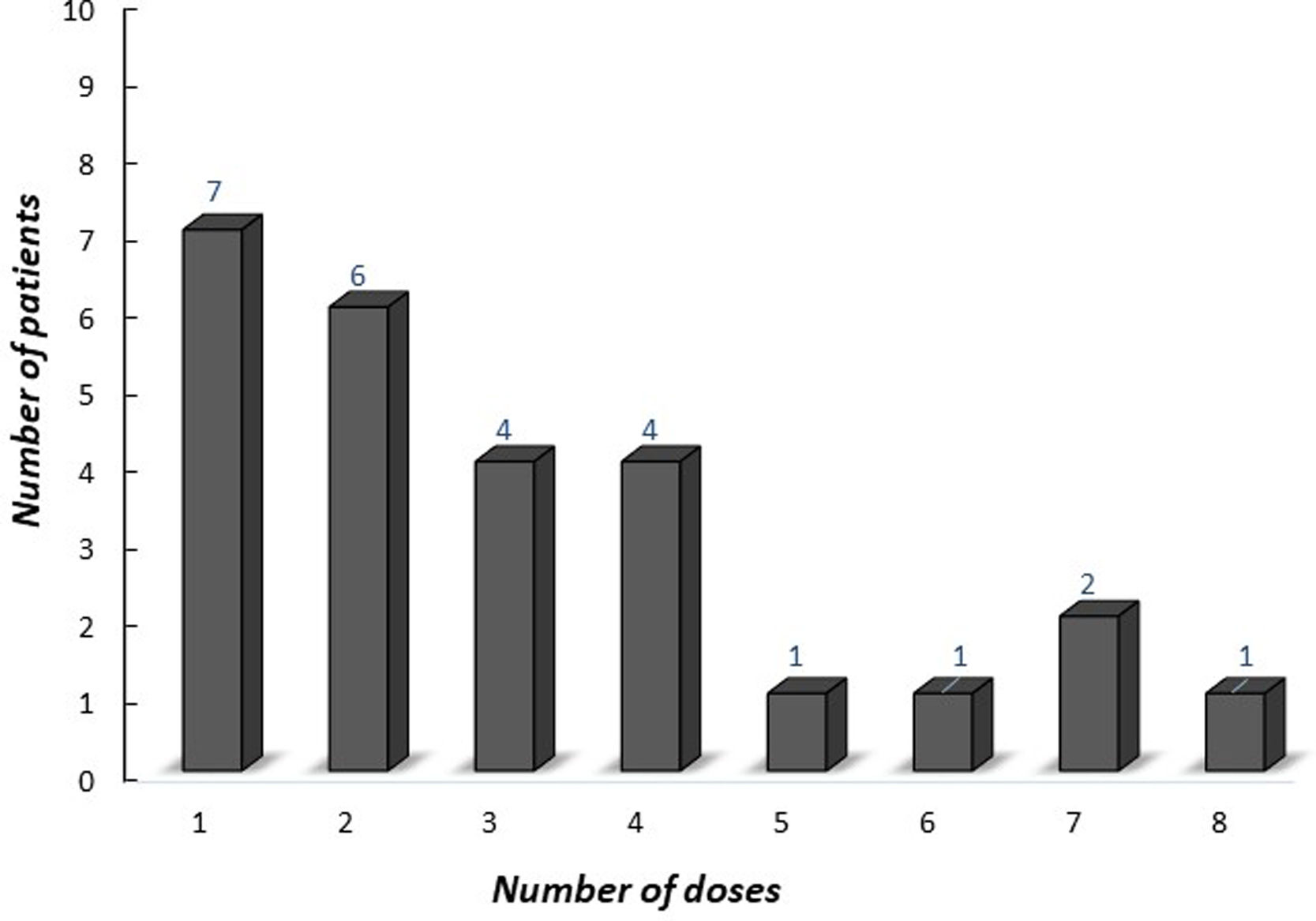

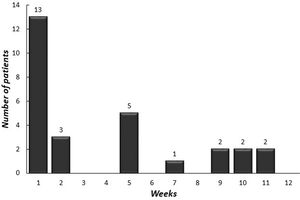

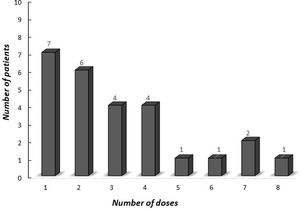

The median age of onset of omalizumab was 15.4 years (IQR 12.9–16.9 years). The median symptom duration was 12 months (IQR 6.5–27.5 months) before the omalizumab treatment. A total of 28 (96.5%) [26 (89.6%) complete, two (6.9%) partial] patients achieved remission with omalizumab. The number of patients who had more than a 30% decline in UAS7 within 12 weeks of treatment is indicated in Fig. 2 according to the weeks. At week 12, after three doses of omalizumab, complete response was reported in 17 (58%) patients (Fig. 3). The median time to achieve a complete response was 7.5 (IQR 3–14.7) weeks. One (3.5%) patient showed no significant change in UAS7 at week 12 so omalizumab was discontinued and the case was accepted as a non-responder. The omalizumab dose interval was extended to six weeks in eight (27.5%) patients.

The adverse effect was observed in only one (3.4%) patient as angioedema after the third dose of omalizumab and asymptomatic two months. Allergy skin tests were performed with omalizumab solution and an intradermal skin test at a dilution of 1:10 was detected positive with a wheal of 10mm. There was no effect of pre-treatment symptom duration (p=0.167) and associated angioedema on symptom disappearance time (p=0.41). Twenty-three of 26 patients who had a complete response and completed the treatment were followed-up for a median of 18 months (IQR, 13–27 months). Relapse was observed in three (13%) patients. The relapse times of three patients were 4, 6, and 12 months after the end of omalizumab therapy.

DiscussionThe omalizumab treatment in adolescents with CSU seems to be highly effective. Nearly 90% of our patients showed a complete response rate and another 6.5% showed a partial response. We experienced only one adverse effect as angioedema, which did not preclude the continuation of the therapy. Within a one-and-a-half-year follow-up period after cessation of omalizumab treatment, 13% of the children with CSU relapsed. Relapses occurred within the first year after cessation of treatment. Omalizumab is considered as an effective and safe treatment for CSU in adolescents.

There are few studies in the literature on the use of omalizumab in children with CSU. Most studies of omalizumab in adult patients guide this treatment option in adolescents and children. Three randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trials, ASTERIA I,10 ASTERIA II9 and GLACIAL,11 demonstrated the efficacy and safety of omalizumab in adults. In these three pivotal studies, ASTERIA I and ASTERIA II included patients who remained symptomatic with H1-antihistamines at approved doses but GLACIAL enrolled patients who were symptomatic despite the suggested combination therapies (up to four-fold dose of H1-antihistamines, plus H2 antihistamines, LTRAs or both H2-antihistamines and LTRAs). Although the methodologies of the studies were different, the similarities in efficacy were emphasized.9–11 In our study, the inclusion criteria were similar to GLACIAL and the number of previous CSU medications was a median of two (IQR, 1–3). Because the adolescents were not the focus of these study populations, they had not been evaluated separately for the efficacy of omalizumab. In a clinical review that had 975 patients with CSU, 39 (4%) were from 12 to under 18 years old. That statistical study had the highest number of adolescent cases in the literature. The mean age of the adolescent group was 15.1 years and most patients were female (69.2%).13 Similarly, the mean age of the group in our study was 15.2 years and most patients were female (56.2%).

A systematic review of 84 observational studies reported the effectiveness of different dosing regimens, such as 150mg/dose every two weeks or every four weeks (Q4W), but most frequently, omalizumab was commenced at 300mg/dose (62.7%) at a frequency of Q4W (83.9%).19 Another study that described response patterns using the data of three pivotal omalizumab trials demonstrated that 300mg of omalizumab could control CSU symptoms well. 15 In our study, we initiated with 300mg/dose Q4W. The omalizumab dose interval was prolonged to six weeks in eight (27.5%) patients since they showed lower UAS7 scores and good responses. It should be noted that individualizing the dose and frequency may increase treatment success.

UAS7 provides semi-quantitative information on disease activity between clinical visits.20 There are variations among studies on the definition of response to treatment in CSU. In most of the studies, the degree of response was classified into complete responders (UAS7=0), partial responders (UAS7≤6 but not 0) and non-responders (UAS>6).21 In our study, we also evaluated our patients according to previous definitions. In ASTERIA II the median time to achieve complete response was eight weeks for the patients who received 300mg omalizumab. The median time for complete response was 12 and 13 weeks in the studies ASTERIA I and GLACIAL for 300mg omalizumab, respectively. At week 12, patients treated with 300mg omalizumab reported UAS7=0; 35.8% for ASTERIA I, 44.3% for ASTERIA II and 33.7% for GLACIAL.9–11 An earlier study by Sussman et al. found a complete response rate of 79% for any point during the study.22 A recent retrospective study by Nettis et al. reported a complete response of 67% 23 In the present study, we found an overall response rate of 96.5%, with only one patient not responding. By week 12, 96.5% of our patients achieved a response (partial or complete), however, 31% of patients gained complete response after the 12th week. These findings were similar to previous adult studies. After the initiation of omalizumab, the possibility of response at different time points may be observed. The time to respond to treatment may vary in adults and children.

In the literature, there is no marked consensus related to the time of discontinuation of omalizumab treatment. Metz et al.24 reported that omalizumab treatment could be continued for 6–12 months. However, the general approach is to specify the treatment period according to the patient's clinical response.25 Some patients may experience relapse after cessation of omalizumab. It is important to know when the medication can be stopped and whether the patients have to be retreated in the event of recurrence of symptoms. A study investigating patients who were at risk of relapse after stopping omalizumab treatment suggested that the speed of symptom return was independent of baseline characteristics of the patients, including duration of CSU, angioedema, previous treatments received, or patient demographics. However, they considered that symptom return could be estimated based on baseline UAS7 and early treatment response.26 In a retrospective study that included 31 patients with refractory CSU it was found that the mean time to achieve complete therapy response was a statistically significant difference between the time to complete response with the first and third course. It was faster as the number of retreatments increased.27

A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study that enrolled patients with antihistamine-resistant CSU was designed to answer questions regarding the benefit of omalizumab treatment after 24 and 48 weeks. It was suggested that continuous treatment with omalizumab was beneficial both for preventing the return of symptoms as well as for achieving sustained control through 48 weeks of treatment.28 In the present study, we continued treatment for at least six months. Only three of our patients experienced a relapse at 4, 6, and 12 months after the end of omalizumab therapy.

The safety of omalizumab has been evaluated in numerous adult studies. The most common adverse events reported were headache (6.1%), sinusitis (4.9%), arthralgia (2.9%) and injection-site reaction (2.7%).29 There were no reports of omalizumab related anaphylaxis in three pivotal studies, ASTERIA I, ASTERIA II or GLACIAL.30 However, one case was reported who experienced anaphylaxis 36h after omalizumab administration.31 Angioedema and urticaria following omalizumab for CSU were stated in four cases.32 In the present study, we observed angioedema in one (3.4%) patient after the third dose of omalizumab.

Clinical and laboratory criteria have not been defined to predict the effectiveness of omalizumab treatment. Positive determinants of omalizumab response, such as absence of angioedema, advanced age, history of short-term disease, no history of immunosuppressant use and negative result on a histamine release test were reported in a study that had 154 CSU patients treated with omalizumab.33 Angioedema has been reported to occur in 40% of patients with CSU and 23.1% in omalizumab clinical trials involving adolescents.13,34 Angioedema was detected in 37.7% of our study population. No significant association was observed between treatment response and demographics, concomitant diseases. In a multicenter study that assessed the safety, efficacy, and predictors of poor treatment outcome of omalizumab in patients with CSU, higher pretreatment IgE levels were found less likely to be associated with poor treatment response.35 In the present study, we did not find any laboratory predictors for poor treatment outcome. However, prospective studies including children under 18 years old would be informative in this setting.

In conclusion, our results indicate that treatment with 300mg/4QW of omalizumab for at least six months is effective and safe for adolescents with CSU. Additional double-blind and placebo-controlled randomized studies are needed to assess the safety and efficacy of omalizumab in this special population.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author contributionsMK wrote the article, ABB and OUS examined the patients and carried out the follow-ups. BES supervised the study and contributed to the discussion. UMS performed the statistical analysis, supervised the study and contributed to the writing process.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there is no conflict of interest and no funding.

There is no funding.