INTRODUCTION

Since 1981, several cases of acrylate-induced asthma have been described, especially in dentists and persons using glues or paints containing these substances 1,2,3.

Acrylic compounds are used in a large variety of products such as adhesives, solvents, paints, printing ink, soft contact lenses, porcelain nails, superglues, and methacrylates (used by dentists and orthopedists). There are several types of acrylic compounds: acrylates, cyanoacrylates (tissue adhesives and home glues), and methacrylates (prostheses and dental and orthopedic fillings). The sensitization mechanism is unknown but is probably due to a non-IgE mediated phenomenon since the late asthmatic response occurs after bronchial challenge.

CASE REPORT

A 52-year-old man who had been working in graphic arts for the previous 7 years attended the Allergy Service for the first time in February 2004. The patient reported a 2-year history of persistent cough, dyspnea on moderate exertion, and weight loss. There was no personal or family history of atopic disease.

In September 2001, the patient presented nasal congestion with pharyngeal pruritus accompanied by dry cough, fever, and wheezing. His symptoms worsened from Monday through Friday, without total recovery on weekends. The worsening was clearly associated with the installation of a printing and drying machine that emitted steam within the work area. These symptoms persisted over months. The patient also showed progressive weight loss of up to 20 kilos and dyspnea on moderate exertion.

In January 2002, the patient was referred to the pulmonology department. His chest X-ray showed a bilateral alveolar pattern and he was diagnosed with toxic pneumonia. He received treatment with oral corticosteroids from February to June 2002, with resolution of the X-ray infiltrates, and some improvement in his respiratory and general health status. Due to the persistence of the respiratory symptoms, he was referred to our service in February 2004. The patient had persistent cough with choking sensation, dyspnea that increased with moderate exertion, and nasal obstruction. He was under treatment with budesonide (360 micrograms) and formoterol (9 micrograms) inhaled every 12 hours. In February 2004, his general health status was good.

The results of previous rhinoscopy were normal and vesicular murmur was decreased on pulmonary auscultation.

Description of the patient's workplace and working conditions

The patient worked in a quality control position for labeling, serigraphy and design in an area that openly communicated with a large 2300 m 2 warehouse. Since the middle of 2001, he had worked directly with flat serigraphic machinery, in which he applied overprint varnish on the plate that was printed. This varnish contained an epoxy liquid resin, isophorone, with a molecular weight of less than 700, 1,6-hexanodiol diacrylate, triacrylate trimetripropane, and isobutyl methacrylate. The varnish was dried by the machinery's ultraviolet light, emanating steam to the work area. In the middle of 2002, the machinery was reconditioned and outlets for most of the steam to the exterior were installed.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Skin tests

Skin prick testing to inhalants (pollens, mites, fungi, and animal dander [ALK-Abello, Madrid, Spain; Bial-Aristegui, Bilbao, Spain]) was performed.

Histamine was used as the positive control and saline solution as the negative control. A test was considered to be positive when erythema greater than 3 mm in diameter developed at 15 minutes of the test, according to the European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology guidelines for allergen standardization and skin tests 4.

Monitoring of peak expiratory flow (PEF)

PEF was measured with a Mini-Wright measurer every 2 hours, except during sleep, for 4 weeks, while the patient was working and subsequently while the patient was on sick leave.

Diffusion capacity of the lungs

By means of carbon monoxide (DLCO) using inert helium gas at 10 %5.

Bronchial challenge with methacholine

The inhaled particles were generated through a De Vilbiss 646 nebulizer model with continuous pressure at 0.28 ml/min. The results were expressed as the concentration of methacholine that produced a fall equal to or greater than 20 % of forced expiratory volume in 1 second (PC20-FEV1). PC20 values of > 16 mg/ml were considered as within the normal range, 1-16 mg/ml as mild bronchial hyperreactivity, 0.125-1 mg/ml as moderate bronchial hyperreactivity, and < 0.125 mg/ml as severe bronchial hyperreactivity.

Specific bronchial challenge

An acrylate exposure test was performed in a 7 m 3 chamber. The patient performed a use test, applying acrylate varnish on a surface for a 5-minute period on the first day. On the second day, the accumulated time was 30 minutes, performed in two 15-minute periods. At all times, FEV1 and forced vital capacity (FVC) were measured at 5, 10 and 20 minutes of exposure. Bronchial challenge was discontinued when there was a decrease in FEV1 ≥ 20 %. Serial spirometries were performed after finishing the bronchial challenge at 30, 40, 50, and 60 minutes. Then, PEF and FEV1 were measured every hour with electronic PEF (PIKO-I, Ferraris) except during sleep. A decrease of FEV1 ≥ 20 % in the first 60 minutes was considered to be an immediate positive reaction and, if the decrease occurred between 2 and 24 hours after the challenge, as a positive late reaction.

Induced sputum and processing: Sputum eosinophil cationic protein (ECP), flow cytometry and cytology

After inhalation of salbutamol, sputum indication was performed with hypertonic saline solution before and after bronchial challenge, as described by Pin et al 6. ECP was measured in the sputum supernatant 7 as inflammatory mediator (normal value is ≤ 45 μg/l) and a flow cytometer with cell pellets 8, and May-Grünwald and Giemsa cell staining for differential counting were also performed. Serum ECP was also measured before and after bronchial challenge 9 (the normal value in our laboratory ≤ 16 μg/l).

RESULTS

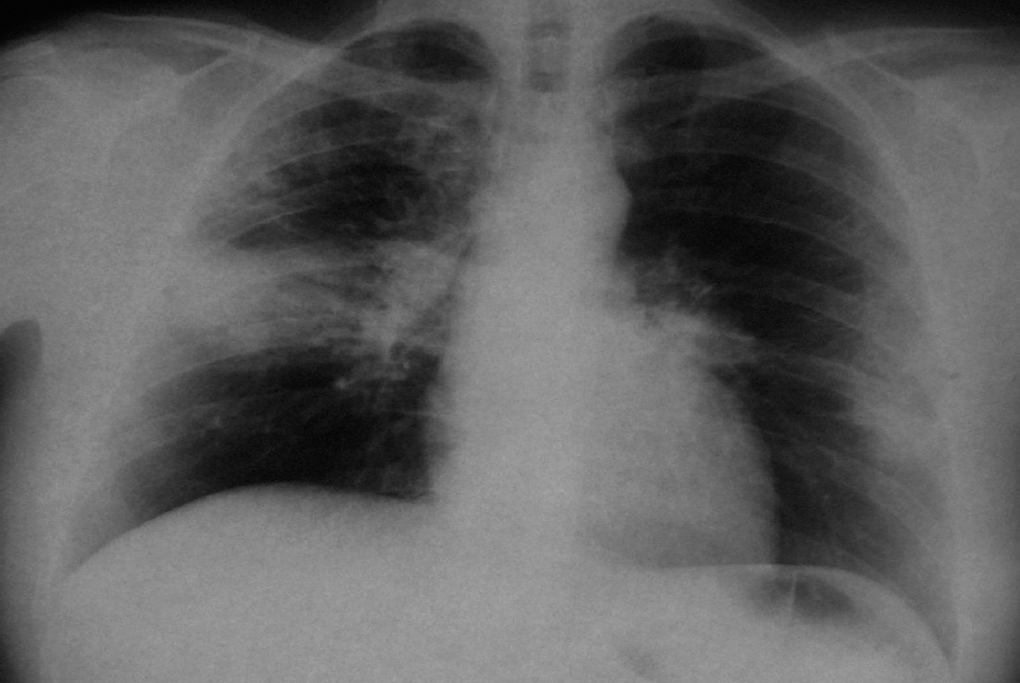

The patient brought a chest X-ray performed in February 2002 showing a bilateral alveolar pattern (fig. 1) and a chest computed tomography scan (fig. 2) taken during the period in which he had acute symptoms. There was consolidation of the left inferior lobes and right middle lobe. Laboratory analyses showed leukocytes 12300 mm 3 (eosinophils 33 %), platelets 576000 mm 3, globular sedimentation rate 105 mm/h, glucose 111 mg/dl and creatinine 0.9 mg/dl.

Figure 1.--CHEST X-RAY 2002: Bilateral alveolar pattern that affected the right upper lobe and apical segment of the right lower lobe and periphery of the left with increase of left hilum.

Figure 2.--CHEST CT SCAN 2002: consolidation area in both inferior lobes and middle lobe with some areas of bronchogram in its interior. Some lymph node abnormalities of significant size in mediastinum.

Chest X-rays were repeated in October 2003 and March 2004, showing disappearance of the acute infiltrates.

The patient was seen for the first time in our service in February 2004. He was still working in the same position and spirometry showed an FVC of 3.51 l (80.6 % of predicted), FEV1 2.19 l (62.3 % of predicted), FEV1/FVC 62.31 % with negative bronchodilation. The skin prick test to inhalants was negative and total IgE was 203 KU/l. In the analysis, he already had 12 % eosinophils, a serum ECP of 61 micrograms/liter and ECP in sputum greater than 200 μg/l.

The causal relationship of these symptoms with acrylate exposure was investigated by serial PEF monitoring at work and outside work. Figure 3 shows the PEF measurements during workdays and after sick leave. The patient was under treatment with budesonide and formoterol. The patient's PEF value improved 6 days after beginning sick leave. After 10 days' sick leave, he stopped using salbutamol. After 2 months of sick leave (May 2004), the patient's serum ECP was 32.7 micrograms/l (values lower than those when he was working) while sputum ECP was still high (> 200 μg/l).

Figure 3.--Diagram of PEF during work and during sick leave. The patient was under treatment with budesonide and formoterol.

During the patient's sick leave, we continued to perform investigations, carrying out pulmonary diffusion for CO, which was normal. The patient had mild bronchial hyperreactivity (PC20: 4 mg/ml) in bronchial challenge with methacholine prior to specific bronchial challenge. The bronchial challenge was conducted the next day with placebo in the empty chamber and was perfectly tolerated. In the following 24 hours, the exposure test to varnish mixed with acrylates was continued in a dynamic chamber. On the first day, no decrease in FEV1 was observed. On the following day, exposure to acrylates was continued for an accumulated time of 30 minutes, and serial spirometries were performed. An isolated late asthmatic response (23 % decrease of FEV1) was observed at 8 hours of exposure, without systemic symptoms and with maintenance of vital signs at all times.

In the bronchial challenge with methacholine at 24 hours of exposure to acrylates, nonspecific bronchial hyperreactivity increased, the patient presenting a PC20 of 1 mg/ml. In post-challenge induced sputum, we observed a considerable increase in eosinophils (13 %), macrophages (4 %), neutrophils (34 %) and lymphocytes (7 %). No changes with respect to previous blood tests, 24-hour post-challenge blood test, or post-challenge chest X-ray were observed and the spirometry value was within the normal range. After 1 month of sick leave, the patient's spirometry was FEV1 3.15 l (89.6 %), FVC 4.53 l (103.9 %) and FEV1/FVC 69.55 %.

DISCUSSION

Cases of dentists, persons working in related occupations, and orthopedists who developed rhinitis and bronchial asthma due to acrylates and even some cases of occupational urticaria have been described in the literature 10,11. Although sensitization to these products is presumed, the mechanism involved could not be discovered. No specific IgE for acrylates was found. Like other authors, we observed a late response to challenge test with eosinophilic inflammation and an increase in bronchial hyperreactivity after exposure, confirming the etiology.

Follow-up PEF, both in the workplace and during the patient's sick leave, with the patient under treatment in both situations, was highly useful and showed wide variations in flows. Although the use of a computed PEF meter is sometimes required to obtain exact values 12, education and training of the patient leads to analyzable results.

Both the response to methacholine and the presence of eosinophils after the bronchial challenge suggest the presence of a specific stimulus rather than possible irritants 13.

The episode our patient suffered in 2002 could have been caused by hypersensitivity pneumonitis or eosinophilic pneumonia rather than by toxic pneumonia due to acrylates.

Evidence that the patient's symptoms were not due to toxic pneumonia is provided by the fact that the patient was the only individual affected in the company, since this form of pneumonia, now known as Ardystil syndrome (one of the most important and recent cases of which occurred in Alicante, in Spain), affects more than one worker and does not depend on the individual's susceptibility or sensitization, but rather on the toxicity of the substance. A characteristic of Ardystil syndrome is the irreversible damage produced by acramin (a substance released from textile aerograph airbrushes) in the bronchi, bronchioles, and pulmonary parenchyma 14,15.

However, eosinophilic pneumonia produces symptoms that may be superimposed on the disease suffered by our patient. Eosinophilic pneumonia is a group of pulmonary disorders characterized by the presence of eosinophilia in peripheral blood, pulmonary infiltrates, cough, dyspnea, fever, wheezing, and asthenia. Eosinophilic pneumonias may be chronic or acute and their etiology is unknown. Shorr et al 16 have described acute eosinophilic pneumonias in American soldiers in the Iraq war and all affected soldiers had recently begun to smoke. Therefore, these authors related tobacco smoke with the development of eosinophilic pneumonia in these solders. An intense and serious response of eosinophilic inflammation due to massive exposure to acrylates can cause an immune response of hypersensitivity, which is what occurred in our patient. Continuous exposure to smaller amounts of acrylates is what produced sensitization to acrylates and persistent bronchial asthma 2 years later.

In conclusion, the cause of the patient's symptoms in 2002 cannot be definitively identified, although we suggest that they could have been due to eosinophilic pneumonia. In agreement with several cases published by Quirce et al 17, bronchial challenge demonstrated that the patient currently has occupational asthma due to acrylate sensitization caused by occupational exposure to this substance.

Correspondence:

I. Reig Rincón de Arellano

Hospital Clínico San Carlos

Profesor Martín Lagos, s/n

28040 Madrid

E-mail: irrda@hotmail.com