To carry out a medical audit or evaluation and improvement procedure on the management of children with asthmatic crises in our Emergency Department (ED).

Material and methodsWe carried out a retrospective audit between January and March 2007, analysing the medical records of a random sample of 50 patients aged 2–14 years consulting our ED for asthmatic crises. Following the international guides, we first selected 17 explicit indicators divided into four domains: “evaluation”, “examination”, “diagnostic resources”, and “treatment and conditions at discharge”.

ResultsIndicators’ compliance proved unequal; it was scarce for cause of asthma crisis (32%); degree of severity (18%); and supportive treatment (24%). Auscultation was registered in 100%, but respiratory frequency only in 49%, and peak flow in 0%. A total of 78% of the patients were treated in the ED, in all cases with beta-mimetic agents, and with systemic corticosteroids in 12%. The result of treatment was registered in only 69% of cases. The medical documentation of resident doctors was not signed by the staff.

ConclusionsWe identified the following weak points: failure to determine the degree of severity; lack of specification of the details of the crisis (prior duration, treatment at home, supportive treatment); scant asthma background history; and deficient recording of respiratory frequency and peak flow. We propose improving the anamnesis, recording respiratory frequency, with the introduction of tools to measure peak flow, specification of treatment response, and the development of a simpler and more practical protocol, with the performance of a re-audit.

Bronchial asthma is common in our setting: an estimated 11% of all children between 6–7 years of age have experienced asthma symptoms at some point. This figure in turn increases to 13% among those aged 13–14 years.1 For the total children aged 6–14 years in the province of Valencia (Spain), the percentage is 8–13.5%.2 On the other hand, it has been calculated that the medical burden associated with asthma care in both adults and in the paediatric population in hospital EDs comes close to 200 episodes per 100,000 inhabitants and year. Moreover, one of every four of these episodes requires admission to hospital.3

As a result of the lack of contrasted evidence-based protocols for the management of acute asthma crises, a considerable number of guides, international consensus documents and expert opinion-based clinical recommendations have appeared in the last decade (GINA,4 GEMA,5 SENP/SEICAP/AEP6), and a number of scientific societies (such as in the United Kingdom) have adopted positions on the issue. On the other hand, a considerable number of hospital centres have developed specific protocols for application to emergency care, based on their particular health care environments.

However, the data found in the literature reflect great heterogeneity in the practical compliance with such recommendations in those centres where their implementation has been analyzed, and it is likewise not fully clear whether the adoption of such recommendations would effectively yield better clinical results than other alternative management approaches.7

Unlike in the Anglo-Saxon countries, clinical self-evaluation is not a consolidated practice in Spain. As a result, there are very few publications on compliance with the mentioned guides or international consensus documents in routine clinical practice-in this case referred to the emergency hospital care, or children with acute asthmatic crises. Medical audits relating to the emergency care of adults with this same disease are also scarce.8

Medical auditing as a procedure for the evaluation and improvement of clinical practice involves the proposition of solutions for dealing with deficiencies found in concrete practice settings. Such audits are carried out by the actual medical professionals in charge of patient care, with the fundamental purpose of improving the latter.9

The present study reports a medical audit of the paediatric emergency care offered in our hospital for children consulting for acute asthma crises, with a view to detecting deficiencies and proposing improvements.

Material and methodsA retrospective analysis was made of the clinical documentation (medical and nursing) on patients seen in the ED of La Fe University Hospital (Valencia, Spain) between January and March 2007, with a diagnosis at discharge of bronchospasm, bronchial asthma with bronchospasm, asthma or bronchial hyper-responsiveness. The study excluded patients under two years of age (in order to exclude bronchiolitis), i.e., the documentation corresponding to children in the 2–14 years age range with these diagnoses at hospital discharge was studied.

The study sample was obtained from the computer-based listing of activities of the ED, applying a fixed selection rate (1/7) to recruit 50 cases in the mentioned time interval. This number is similar to that determined for the audit on asthma attacks in adults carried out in our hospital in 2004 and repeated in 2007, and is in line with other similar studies following a batch sampling plan (BSP) model.10 The data were collected by two evaluators (BF, CM) using a worksheet developed to that effect, and guaranteeing patient and physician anonymity. In line with other similar studies found in the literature, a target sample of 50 cases or clinical processes was established.

Following the medical audit methodology,11 we first established a series of objective and explicit dichotomic (except as refers to drug doses and duration of the current asthma crisis) criteria or indicators, based on a review of the international consensus documents on the management of asthma crises; the recommendations of the ED of our own hospital; and benchmarking similar studies published in the scientific literature.

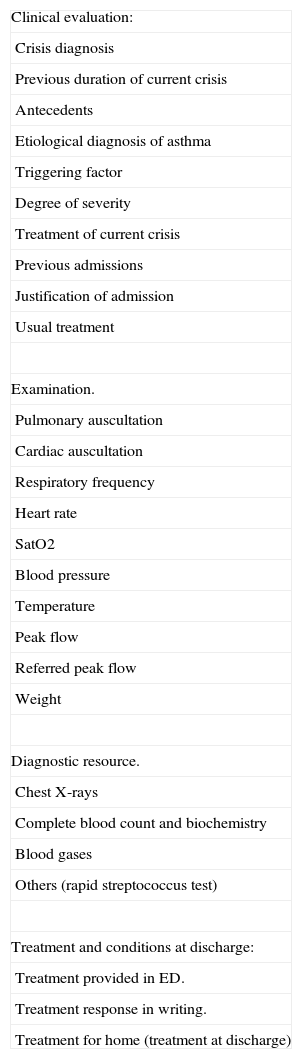

The clinical indicators were grouped into four domains: “clinical evaluation”, “examination”, “diagnostic resources”, and “treatment and conditions at discharge” from the ED (Table 1).

Clinical indicators

| Clinical evaluation: |

| Crisis diagnosis |

| Previous duration of current crisis |

| Antecedents |

| Etiological diagnosis of asthma |

| Triggering factor |

| Degree of severity |

| Treatment of current crisis |

| Previous admissions |

| Justification of admission |

| Usual treatment |

| Examination. |

| Pulmonary auscultation |

| Cardiac auscultation |

| Respiratory frequency |

| Heart rate |

| SatO2 |

| Blood pressure |

| Temperature |

| Peak flow |

| Referred peak flow |

| Weight |

| Diagnostic resource. |

| Chest X-rays |

| Complete blood count and biochemistry |

| Blood gases |

| Others (rapid streptococcus test) |

| Treatment and conditions at discharge: |

| Treatment provided in ED. |

| Treatment response in writing. |

| Treatment for home (treatment at discharge) |

Following data collection and tabulation, the corresponding evaluation sessions were programmed by a “group for improvement” composed of the authors of the present work and the Head of Department, with a view to identifying the strong and weak points, and to define solutions for improvement. Accordingly, attention centred on the deficiencies identified or areas for improvement, and on the definition of realistic options for improvement.

The results were expressed as percentages of the corresponding total, rounding off to the nearest whole number, in order to avoid the presence of decimal values in the tables.

For increased convenience, the following significance thresholds or cut-off points were established a priori: adequate indicators compliance=compliance ≥85%, and notoriously deficient indicators compliance=compliance<30%. The range between both extremes was taken to correspond to the intermediate BSP assessment interval (J. Valadez ).10

In the cases of medication, we analyzed the dose referred to patient body weight, according to the internal protocol of the hospital.

Only the data reflected in the area of clinical documentation were considered (medical and nursing), assuming that the information not contained in the documents is not evaluable and precludes the continuity of medical care by other colleagues.

ResultsA total of 50 useful episodes were documented, corresponding to 50 children with asthmatic crises who reported to the ED during the referred period of time. Only one patient required admission to the Monitorisation Unit, and there were no referrals to Intensive Care. The rest of the children were sent home with written instructions for posterior paediatrician control.

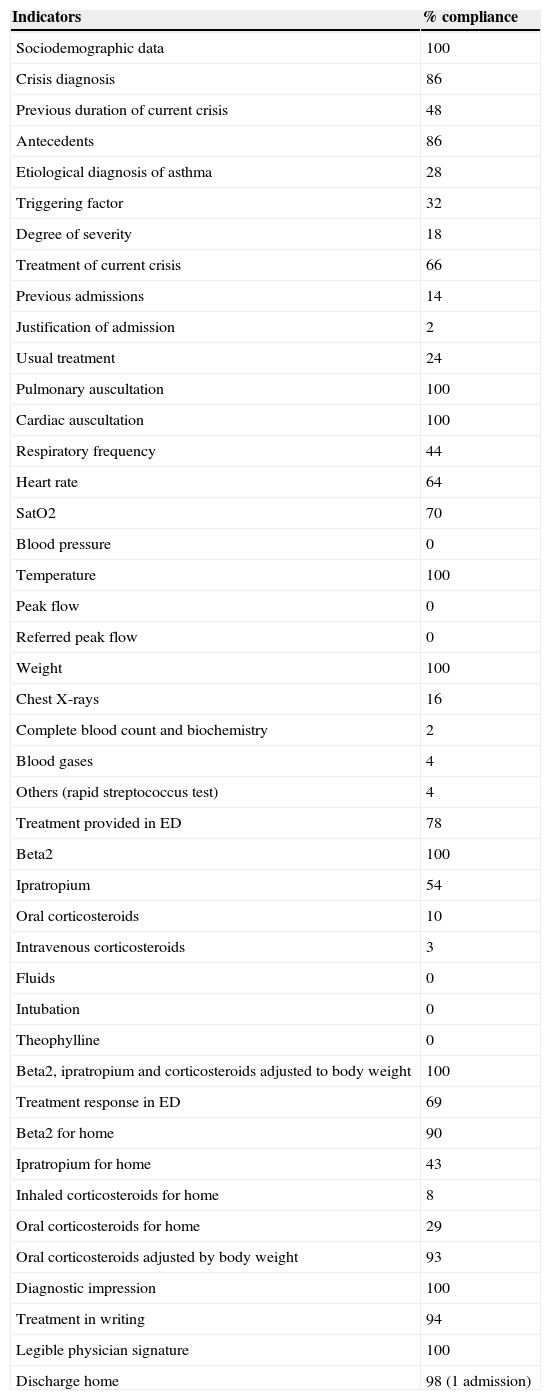

The compliance with the different indicators is reported in Table 2.

Compliance with the different indicators, expressed as percentages

| Indicators | % compliance |

| Sociodemographic data | 100 |

| Crisis diagnosis | 86 |

| Previous duration of current crisis | 48 |

| Antecedents | 86 |

| Etiological diagnosis of asthma | 28 |

| Triggering factor | 32 |

| Degree of severity | 18 |

| Treatment of current crisis | 66 |

| Previous admissions | 14 |

| Justification of admission | 2 |

| Usual treatment | 24 |

| Pulmonary auscultation | 100 |

| Cardiac auscultation | 100 |

| Respiratory frequency | 44 |

| Heart rate | 64 |

| SatO2 | 70 |

| Blood pressure | 0 |

| Temperature | 100 |

| Peak flow | 0 |

| Referred peak flow | 0 |

| Weight | 100 |

| Chest X-rays | 16 |

| Complete blood count and biochemistry | 2 |

| Blood gases | 4 |

| Others (rapid streptococcus test) | 4 |

| Treatment provided in ED | 78 |

| Beta2 | 100 |

| Ipratropium | 54 |

| Oral corticosteroids | 10 |

| Intravenous corticosteroids | 3 |

| Fluids | 0 |

| Intubation | 0 |

| Theophylline | 0 |

| Beta2, ipratropium and corticosteroids adjusted to body weight | 100 |

| Treatment response in ED | 69 |

| Beta2 for home | 90 |

| Ipratropium for home | 43 |

| Inhaled corticosteroids for home | 8 |

| Oral corticosteroids for home | 29 |

| Oral corticosteroids adjusted by body weight | 93 |

| Diagnostic impression | 100 |

| Treatment in writing | 94 |

| Legible physician signature | 100 |

| Discharge home | 98 (1 admission) |

Relating to domain 1, “clinical evaluation”, the results varied between 14% for previous admissions for this disease, to 86% as refers to the documentation of bronchospasm episodes. The grading of disease severity was recorded in 18% of the cases.

Relating to the indicators for “examination”, the compliance was found to be 100% for cardiopulmonary auscultation, weight and temperature. In contrast, peak flow was not registered in any case. Respiratory frequency was documented in 44% of the cases.

Relating to the consumption of “diagnostic resources” we found that 78% of the patients were subjected to treatment. In 100% of these cases inhalatory beta-mimetic agents were prescribed, while 13% received systemic corticosteroids. In the ED, medication was adjusted to body weight in all cases. In no case were fluids, intubation or theophyllines used. Lastly, the response to treatment provided in the Emergency setting was documented in 69% of the cases.

The scant documentation of severity precluded correlation of the use of corticosteroids and the severity of the asthma crises to the data obtained.

Regarding the recommended treatment and the conditions of discharge from the ED (Table 2), all patients had a written report with the legible signature of the physician, and the prescribed medication was adjusted to body weight in 93% of the cases. Patient care was provided by a staff physician in 30% of the cases and by a first-year resident in 38% of the cases. The rest of the patients were attended by second, third and fourth year residents. No staff physician signatures appeared on the reports issued by the residents. The first year residents had entered the postgraduate training program (Médicos Internos Residentes, MIR) nine months before the period selected for data collection.

DiscussionOur results coincide with other similar studies and reflect important variability in compliance with the previously selected indicators based on the consensus recommendations regarding the management of childhood asthma crises. Overall, our compliance rate did not reach 50%, and fell far short of the best performance published in the literature (79%).14

Of note was the scant documentation of the severity of the asthma episodes. This is important, since in theory the severity of the condition defines the subsequent intervention measures and priorities.

Although it may be assumed that the supervising physician mentally evaluated severity without actually reflecting it in writing, failure to adequately document the parameter complicates the continuity of medical care.

In addition, some of the established criteria for assessing severity, such as respiratory frequency or oxygen saturation, were also rarely documented. This fact may be of relevance to asthma morbidity-mortality, as defended by some authors.13

We cannot establish comparisons with other similar paediatric studies in either our own hospital or in other institutions of this same country, since a Medline and Indice Medico Español literature search closing in February 2008 failed to identify any such studies.

In 2004 and 2007 we performed similar audits in adults in the ED of our hospital, which operates autonomously and independently of the paediatric ED. These audits on adults asthma attacks (age over 14 years)8 detected some similar deficiencies: the severity of the crisis was registered in 32% of the cases; respiratory frequency in 27%; and peak flow in 20% of the cases. There was an important use of diagnostic resources such as chest X-rays, complete blood count and basic biochemical testing in 100% of the cases. As an anecdote, blood coagulation parameters were requested in 39% of the adult patients, and 30% of the discharge reports were printed and in no case carried a staff physician signature.

Similar studies have been published in other countries and health care settings. Barnett,14 in a hospital in Melbourne, conducted an audit of the medical care received by children between 5–17 years of age with asthma attacks. Both the degree of severity and capillary oxygen saturation determined by pulsioxymetry were documented in less than 10% of the cases, while vital signs such as respiratory frequency and heart rate were recorded in 80% and 72% of the cases, respectively. Written treatment follow-up was observed in 66% of the cases. The authors postulated that saturation and treatment measures were probably made but not registered.

Similar data have been published by Dawson in Australia7 in children between 5–15 years of age. The estimation of severity was documented in 47% of the cases, though in only 1.8% was such an estimation based on objective information. In turn, oxygen saturation and peak flow measurements were registered in 35% and 60% of the cases, respectively, although with no evaluating accompanying comments.

In a multicentre study published by Hewer9 in six hospitals of the United Kingdom, involving children between 5–15 years of age, important discrepancies were found in the records of cases attended among the participating centres. The documentation of percentiles varied from 20–81%, oxygen saturation from 3–90%, and treatment prescription at discharge from 26–100% of all cases, depending on the hospital.

Reynolds15 analysed the practical impact of the publication and diffusion of guides, specifically of the recommendations of the SIGN (Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network and British Thoracic Society), upon asthma crisis management in children over two years of age. The study showed these recommendations to have had no impact upon daily practice in the ED compared with the situation one year before their introduction. The only exception in favour of the guidelines referred to duplication of the inhaled corticosteroid dosage during the crises. In this context, some authors such as Crain16 consider the scant recording of severity and deficient adherence to the daily practice guidelines to be a generalised practice.

From this perspective, Doherty12 in 2007 proposed a strategy for the implementation of guidelines in Tamworth Rural Hospital (New South Wales). This strategy is based on 9 points, the first of which is identification of the gaps or weak points of the institution, reformulation or adaptation of the guides, the formation of a multidiscipline implementation team, the compiling of senior staff opinions, and the conduction of audits. The intervention comprises an important number of presentations to the hospital (over 50). With this costly strategy it proved possible to increase the combined compliance index from 47% to 79% one year after implementation. Doherty used seven indicators: documentation of severity, space-chamber use, the use of ipratropium in mild asthma, and spirometry, among others. Such important resource utilisation to secure guideline implementation can be understood in countries such as Australia and New Zealand, where asthma affects up to 40% of the population and constitutes a genuine public health problem.

It could be thought that the mean severity of asthma disease in our series, where 13% received systemic corticosteroids, is less than that recorded in the United Kingdom and Australia, where such medication is prescribed in 83% and 89% of all cases, respectively. Since the degree of disease severity is the least documented parameter, this is, however, mere speculation. It should be pointed out that in our study there were no readmissions due to asthma in the 30 days following patient care.

This lack of concordance between the recommendations and actual clinical practice raises reasonable doubts as to the universal validity of the guides. In reality, while such recommendations have undeniable academic value, they perhaps require improved adaptation to the setting in which they are to be applied.

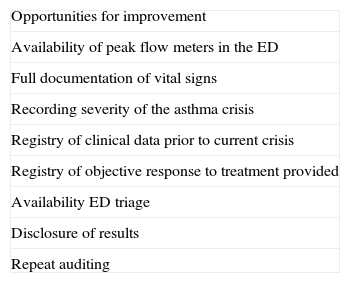

To summarise, the main defects identified in our study refer to failure to adequately evaluate the severity of the asthma crisis; the non-documentation of relevant factors of the current crisis (previous duration, triggering factors, home treatment); and failure to record the patient antecedents (previous admissions for the same problem, etiological diagnosis of asthma). In turn, little mention is made of respiratory frequency, heart rate, oxygen saturation, blood pressure, peak flow, or of response to the treatment provided in the ED. Staff supervision is likewise little mentioned. Some opportunities for improvement were proposed, as shown in Table 3.

Opportunities for improvement

| Opportunities for improvement |

| Availability of peak flow meters in the ED |

| Full documentation of vital signs |

| Recording severity of the asthma crisis |

| Registry of clinical data prior to current crisis |

| Registry of objective response to treatment provided |

| Availability ED triage |

| Disclosure of results |

| Repeat auditing |

The possibility of conducting an audit after a certain period of time is suggested, to assess the impact of the proposals for improvement in relation to the detected shortcomings.

In the present study, use was made of an important number of indicators, since we lacked prior data or relevant results. For the purpose of simplifying future studies, it would be advisable to limit the number of indicators, e.g., by grading severity according to objective criteria, with the measurement of oxygen saturation and peak flow, to offer a global view of the subject.

Lastly, we consider that this is an initiative which consumes few resources and has a greater potential for securing improvements, while at the same time allowing monitorisation activities to be carried out. Among other factors, improvement in health care requires real implication and participation on the part of the professionals in charge of providing medical care. We thus consider medical audits, conducted in a professional and cooperative setting, to also constitute a decisive training tool that should be incorporated to the postgraduate resident in training programmes of our hospitals.

The authors thank Dr. Juan Aragó, Head of the Emergency Department, for his support and unconditional help, and the nursing personnel of the Emergencies Area of La Fe Children's Hospital, for their daily dedication.