The aim was to investigate prognostic relevance of history of allergy in subjects with unstable angina treated with coronary angioplasty.

MethodsFifty-seven consecutive patients with unstable angina who underwent coronary angioplasty were enrolled in the study and were divided into two groups: those with a history of allergy (Group A, N=15); and controls (Group C, N=42). Major adverse cardiac events were recorded over a six-month follow-up period. Patients with primary or unsuccessful angioplasty and patients treated with drug eluting stent were excluded from the study.

ResultsGroup A patients (history of allergy) showed a 46.67% incidence of major adverse cardiac events at six-month follow-up (vs. 9.52% Group C, p<0.01): results remained significant even in a multiple Cox regression analysis (hazard ratio 7.17, 95% CI 1.71–29.98, p<0.01).

ConclusionHistory of allergy is an independent predictor of major adverse cardiac events after coronary angioplasty in a six-month follow-up period in unstable angina.

Previous studies reported a link between disease characterised by immune disorders and coronary artery disease.1 Both conditions share inflammatory mechanisms and inflammatory mediators are involved in the clinical progression of both diseases.1 Atherosclerosis is characterised by an immune activation of Th1 lymphocytes2 and activated inflammatory pathways were found alongside plaque progression and disruption.3,4 Also coronary angioplasty triggers an inflammatory response5,6 according to some studies related to mid-term prognosis.7 In a previous paper, cytokines involved in allergic immune disease, mostly released by Th2 lymphocyte such as interleukin(IL)-4 and IL-13,8 were described in the inflammatory activation following coronary angioplasty.9 In this study, we therefore aimed to investigate the prognostic role played by history of allergy characterised by Th2 activation in subjects with unstable angina (UA) treated with coronary angioplasty.

MethodsFifty-seven consecutive patients with UA who underwent coronary angioplasty were enrolled in the study and were divided into two groups: those with a history of allergy (Group A, N=15); and controls (Group C, N=42).

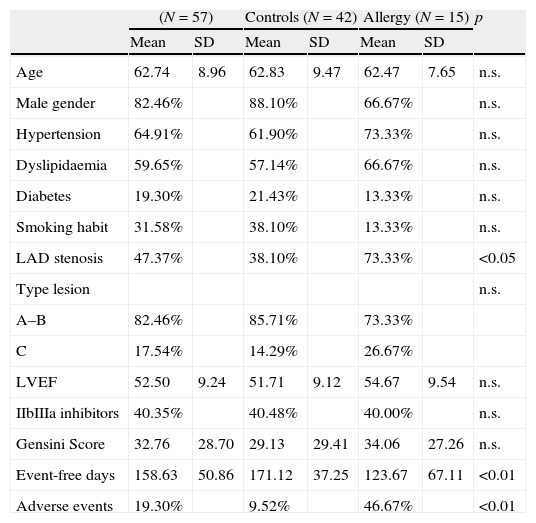

History of allergy was defined as a prior diagnosis of urticaria; angio-oedema; allergic rhinitis; atopic dermatitis; allergic asthma; or anaphylactic reactions. Allergic patients underwent a preventive treatment with histamine and steroids before coronary angioplasty in order to minimise the risk of allergic reaction during procedure. Principal clinical characteristics, left ventricular ejection fraction, Gensini Score10 and American Heart Association type of coronary lesion11 treated with angioplasty were ascertained: data are reported in Table 1.

Patients’ characteristics.

| (N=57) | Controls (N=42) | Allergy (N=15) | p | ||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Age | 62.74 | 8.96 | 62.83 | 9.47 | 62.47 | 7.65 | n.s. |

| Male gender | 82.46% | 88.10% | 66.67% | n.s. | |||

| Hypertension | 64.91% | 61.90% | 73.33% | n.s. | |||

| Dyslipidaemia | 59.65% | 57.14% | 66.67% | n.s. | |||

| Diabetes | 19.30% | 21.43% | 13.33% | n.s. | |||

| Smoking habit | 31.58% | 38.10% | 13.33% | n.s. | |||

| LAD stenosis | 47.37% | 38.10% | 73.33% | <0.05 | |||

| Type lesion | n.s. | ||||||

| A–B | 82.46% | 85.71% | 73.33% | ||||

| C | 17.54% | 14.29% | 26.67% | ||||

| LVEF | 52.50 | 9.24 | 51.71 | 9.12 | 54.67 | 9.54 | n.s. |

| IIbIIIa inhibitors | 40.35% | 40.48% | 40.00% | n.s. | |||

| Gensini Score | 32.76 | 28.70 | 29.13 | 29.41 | 34.06 | 27.26 | n.s. |

| Event-free days | 158.63 | 50.86 | 171.12 | 37.25 | 123.67 | 67.11 | <0.01 |

| Adverse events | 19.30% | 9.52% | 46.67% | <0.01 | |||

Major adverse cardiac events (MACEs) (recurrent angina or acute myocardial infarction, sudden death, target lesion revascularisation) were recorded over a six-month follow-up period. Events were ascertained by direct or telephone contact with the patient or, in the event of death, the next of kin.

Patients with primary or unsuccessful coronary angioplasty and patients treated with drug eluting stent were excluded from the study. Drug eluting stents were excluded in order to minimise the blunted inflammatory reaction elicited by this kind of stents.9

All patients gave a written informed consent. The study was approved by the local ethics committee.

Statistical analysisContinuous variables were expressed as mean value±standard deviation and categorical variables as percentages. Differences in percentages were analysed with the χ2 test. Mean values for continuous variables were compared with Student's t-test. Survival analysis was performed with the Log-Rank test and survival rates were shown with Kaplan–Meier curves; a multiple Cox regression model was used to analyse survivals adjusted for potential confounders. A p value <0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

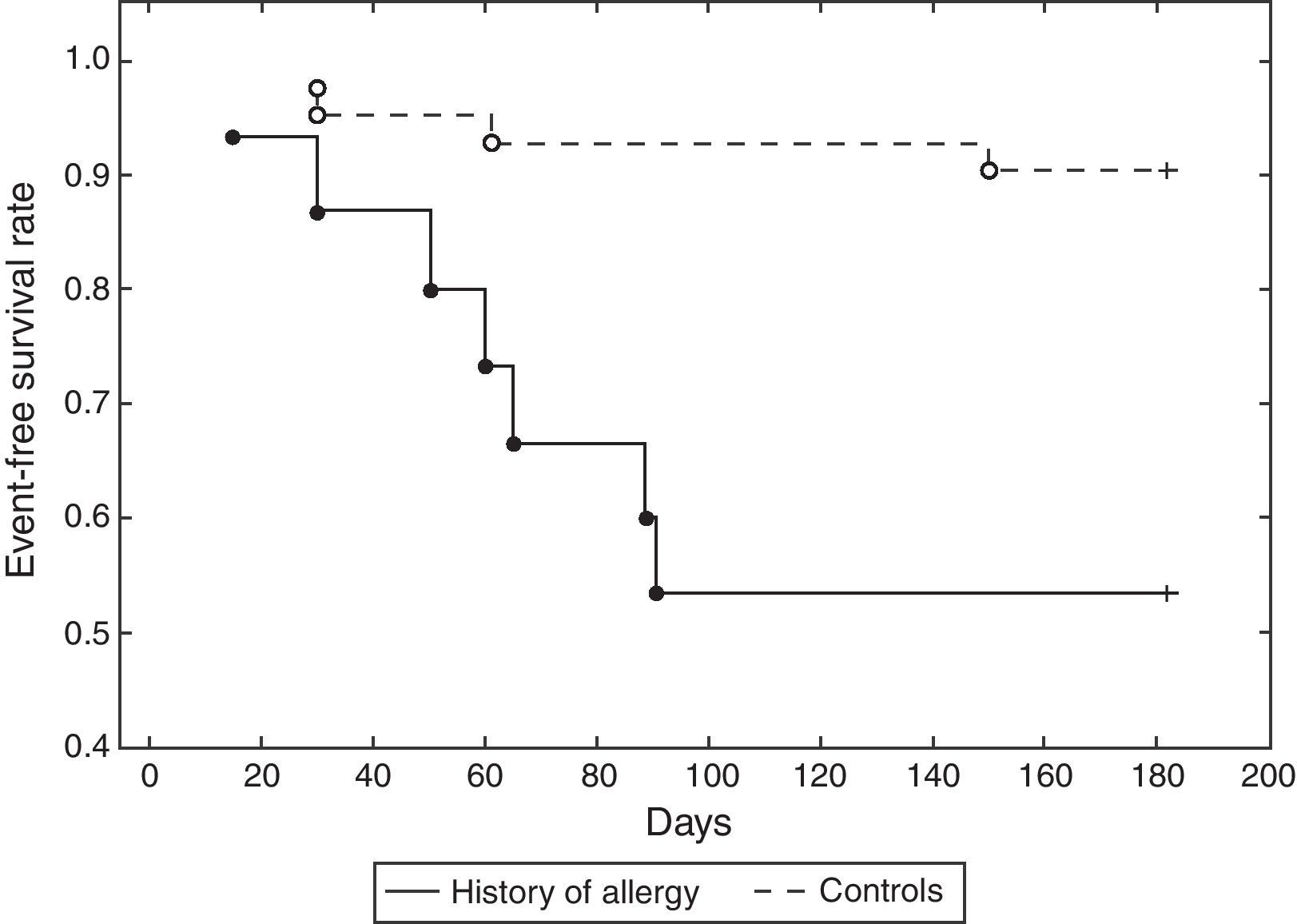

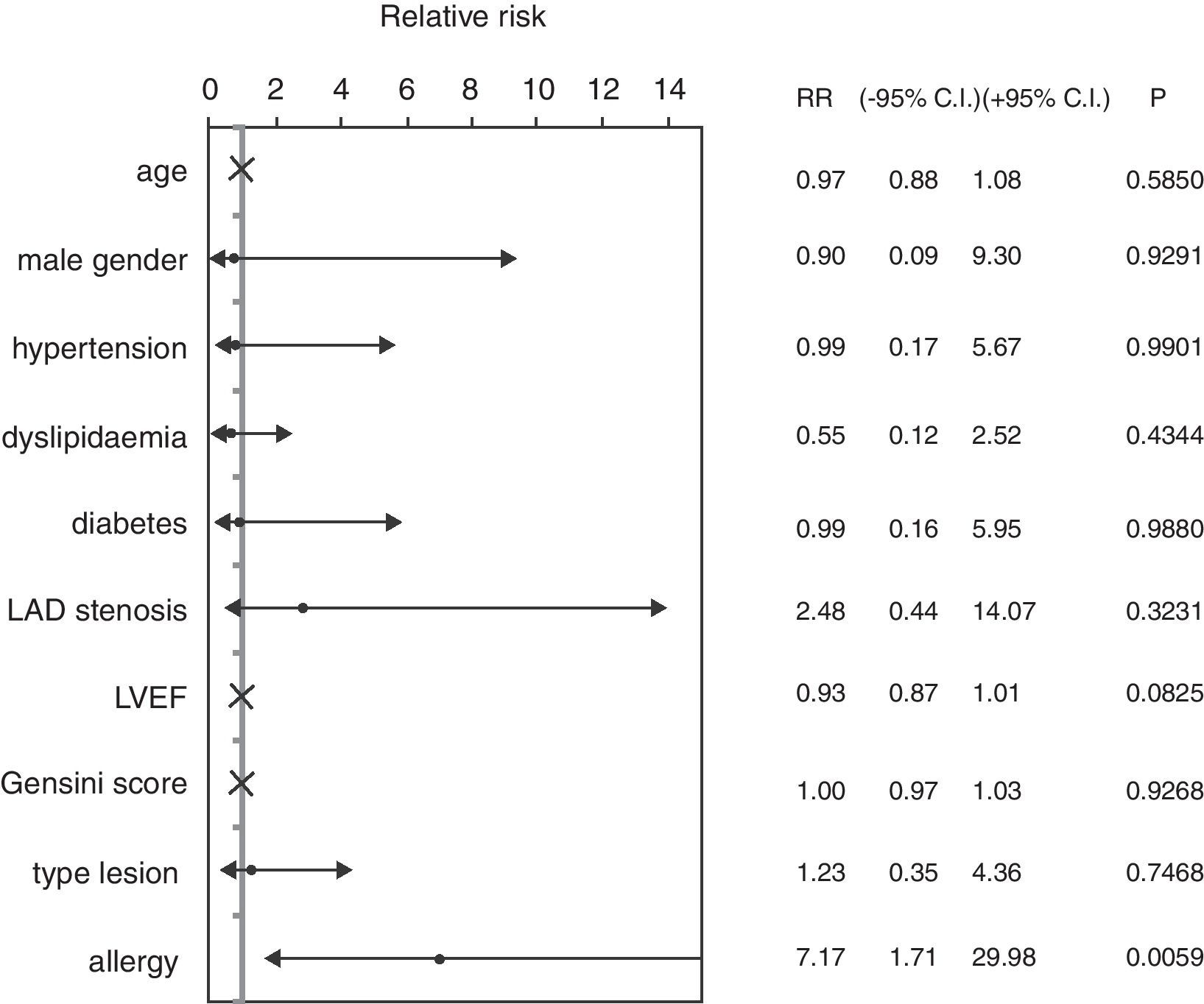

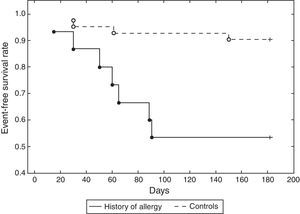

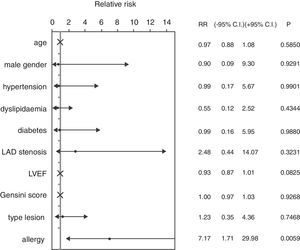

ResultsThe mean age of patients was 62.74±8.96 years, 82.46% were male, 59.65% were diabetics, in 47.37% of cases the treated vessel was left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery. Groups A and C did not show significant differences, except in the rate of angioplasty on LAD. Group A patients showed a 46.67% incidence of MACEs at six-month follow-up (vs. 9.52% Group C, p<0.01) (Fig. 1) (five cases of restenosis, one death, three repeat PCI, eight recurrent angina, four urgent CABG). History of allergy was associated with an increased risk of adverse events (Log-Rank p<0.01). Results remained significant even after correction for age, gender, cardiovascular risk factors, left ventricular ejection fraction, Gensini Score, type of lesion, and treated coronary vessel in a multiple Cox regression analysis (hazard ratio 7.17, 95% C.I. 1.71–29.98, p<0.01) (Fig. 2).

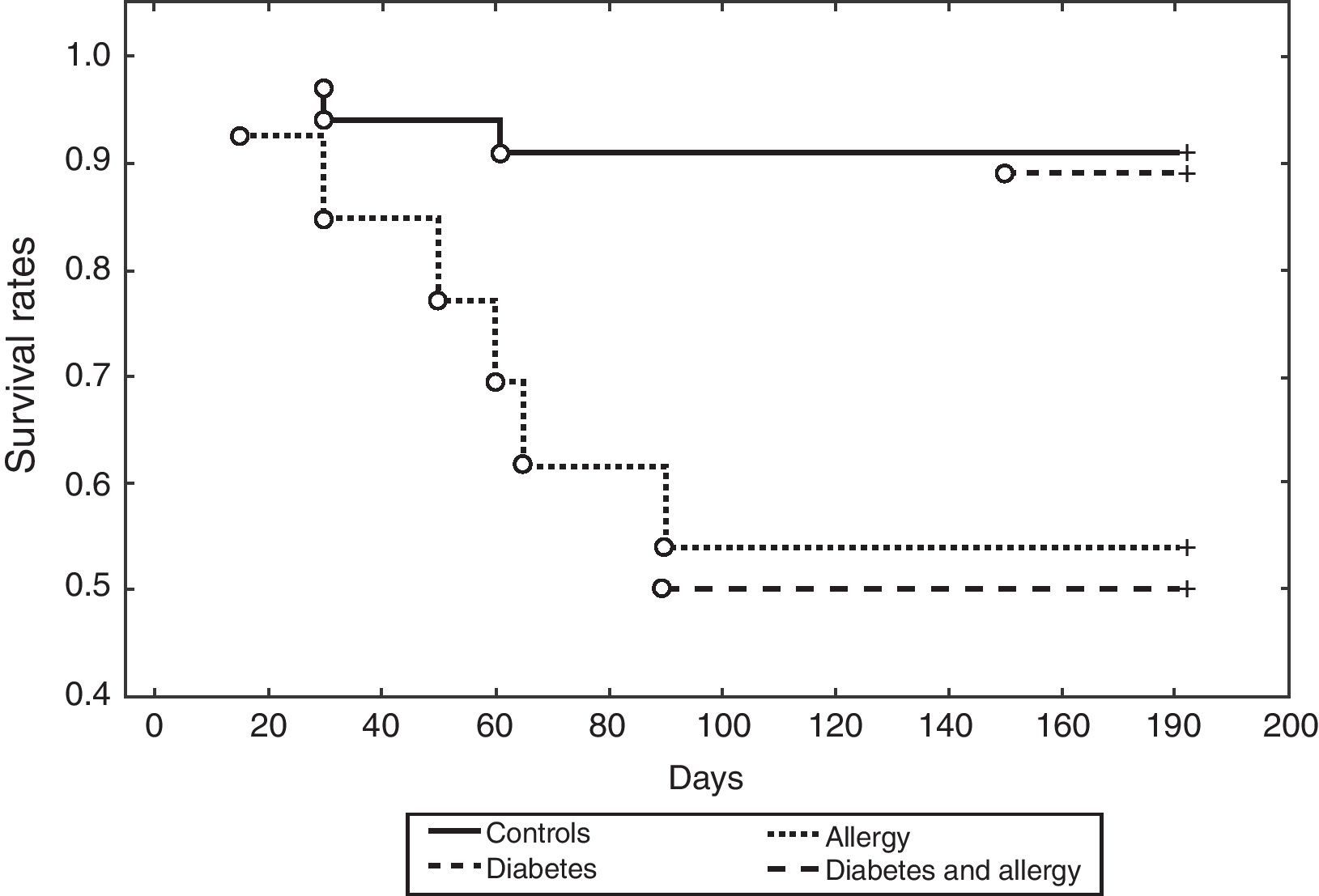

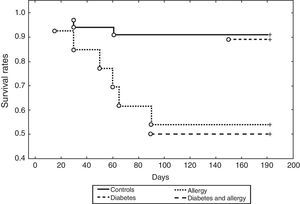

There is a cumulative effect between diabetes and history of allergy on incidence of MACEs after coronary angioplasty (Log-Rank p<0.05) (Fig. 3).

DiscussionTo the best of our knowledge, this is the first study reporting the independent prognostic role played by history of allergy in patients with UA treated with coronary angioplasty. Previous studies reported some cases of metal allergy leading to early recurrence of target lesion revascularisation,12 while in this study an increased rate of cardiac adverse events after coronary angioplasty was shown, regardless of stent metal allergy.

Pivotal evidence coming from Kounis et al. previously showed a link between allergic reactions, acute coronary syndrome (ACS)13 and stent thrombosis after coronary angioplasty.14,15 The stented and thrombotic areas are infiltrated by inflammatory cells including eosinophils, macrophages, T-cells and mast cells.16 Stent components include the metal strut which contains nickel, chromium, manganese, titanium, molybdenum, cobalt–chromium: all these components constitute an antigenic complex inside the coronary arteries which apply chronic, continuous, repetitive and persistent inflammatory action capable to induce Kounis syndrome.17

Recently, common allergic symptoms, such as rhinoconjunctivitis without wheezing and wheezing, were shown to be significantly associated with an increased risk of coronary heart disease.18 Allergic mediators such as histamine, neutral proteases (tryptase, chymase, cathepsin-D), arachidonic acid products (leukotrienes, PAF, thromboxane) have important cardiovascular actions.19 Patients with ACS of non-allergic aetiology have been found to have more than twice the blood concentration of histamine20 and histamine concentration was found to be elevated in patients suffering from attacks of variant angina.21 Arachidonic acid metabolites such as thromboxane and leukotrienes have been found significantly higher in the systemic arterial circulation in the acute stage of non-allergic myocardial infarction.22 Arachidonic acid products such as leukotrienes and thromboxane were significantly higher in non-allergic patients with UA.23 Tryptase levels were elevated in patients with non-allergic ACS with higher concentration in the ST-segment depression group of patients24 and tryptase levels were also found to be elevated in non-allergic patients with significant coronary artery disease as a result of chronic low-grade inflammatory activity present in the atherosclerotic plaques.25 Tryptase levels were found elevated during spontaneous ischemic episodes in patients suffering from UA,26 but not after ergonovine-provoked ischemia in five patients suffering from variant angina, suggesting that a primary yet unknown stimulus activates mast cells in patients suffering from episodes of UA. Therefore, the same substances from the same cells are present in both acute allergic episodes and ACS.

Blood eosinophil count, basophil and IgE levels were found to be increased in patients with ACS.27–29 A subset of platelets bring in their surface membrane both high affinity (RC

Immune disease, such as rheumatoid arthritis, is associated with excess morbidity and mortality from myocardial infarction and allied disorders31,32 and a large body of evidence supports the involvement of common pro-inflammatory cytokines in the development and progression of atherosclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, and systemic lupus erythematosus.33 Pathogenic mechanisms include pro-oxidative dyslipidaemia, insulin resistance, prothrombotic state, and hyperhomocysteinaemia.34,35

However, the link between diseases with an immune mechanism and ACS is not entirely known. Endothelium dysfunction,36 increased arterial stiffness,37 a reduced number and impaired function of endothelial progenitor cells38 and a blunted response to nitric oxide in vivo39 are detectable in auto-immune disease. The frequency of coronary spastic angina tends to be higher in patients with connective tissue disease than in those without.40

Th2 cytokines (IL-4, IL-13), involved in several allergic disease41 and auto-immune disease,42 can also induce a pro-inflammatory environment by means of the oxidative stress.43 Deeper although still only partially investigated relations at gene level may be hypothesised between allergic disease, immune disease and coronary artery disease.44,45 A Th2 cytokines activation, however, proportional to angiographic severity of coronary atherosclerosis, was previously documented also after coronary angioplasty,9 thus providing a possible explaining mechanism for early recurrence of adverse cardiac events after coronary angioplasty in allergic patients.

Potential therapeutic roles for well-established anti-atherogenic drug such as statins46 or cytokines inhibitors47 need to be investigated in this subset of patients with allergic disease and coronary artery disease in further studies enrolling larger cohorts of patients.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no potential conflict of interest to disclose.