Several countries or regions within countries have an effective national asthma strategy resulting in a reduction of the large burden of asthma to individuals and society. There has been no systematic appraisal of the extent of national asthma strategies in the world.

MethodsThe Global Asthma Network (GAN) undertook an email survey of 276 Principal Investigators of GAN centres in 120 countries, in 2013–2014. One of the questions was: “Has a national asthma strategy been developed in your country for the next five years? For children? For adults?”.

ResultsInvestigators in 112 (93.3%) countries answered this question. Of these, 26 (23.2%) reported having a national asthma strategy for children and 24 (21.4%) for adults; 22 (19.6%) countries had a strategy for both children and adults; 28 (25%) had a strategy for at least one age group. In countries with a high prevalence of current wheeze, strategies were significantly more common than in low prevalence countries (11/13 (85%) and 7/31 (22.6%) respectively, p<0.001).

InterpretationIn 25% countries a national asthma strategy was reported. A large reduction in the global burden of asthma could be potentially achieved if more countries had an effective asthma strategy.

Asthma is a common chronic disease affecting an estimated 241 million children and adults in the world according to the estimates of the Global Burden of Disease 2013,1 which also estimated that asthma was the 15th highest ranked cause of Years Lived with Disability.1 Many people with asthma are unnecessarily disabled, because they are not receiving optimal asthma management.2 In 2013, it was estimated that about 22 million disability-adjusted life years are lost because of asthma.3 The International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) found that the historical view of asthma being a disease of high-income countries (HICs) no longer holds: most people affected are in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), and asthma prevalence is estimated to be increasing fastest in those countries,4 where most of the world's people live.

To reduce the burden of asthma, several HICs and LMICs have developed an asthma strategy (or an asthma programme which is the terminology used by some countries) at a national or regional level which has resulted in rapid reduction of the ill-effects of asthma.5 The strategies or programmes are formalised with political engagement and commitment. Implementation of such strategies includes relatively simple measures which are consistently applied in the relevant population, to improve early detection of asthma and provide access to effective anti-inflammatory treatment. Extension of this approach to other countries or regions within countries could be of great potential benefit to reducing the burden of asthma in the world.

The first comprehensive national asthma strategy was developed in Finland in 1994 and has served as a model for other countries. They developed and called it a comprehensive nationwide Asthma Programme and over the next decade this lessened the burden of asthma on individuals and society and more than halved the total asthma costs (healthcare, drugs, disability, and productivity loss)6,7 and these benefits have continued.8 This model was followed several years later by several other national strategies within the European Union9 including France,10 Portugal,11 and Spain.12 In other places, independent approaches have been used with improved outcomes, including Australia,13 the city of Salvador, Brazil,14 Canada,15 Costa Rica,16 Singapore,17 Tonga18 and Turkey.19

However, there are few reports of such strategies, suggesting that in many countries there is no strategy or it has not been implemented. However there has been no systematic appraisal of the numbers of countries in the world which have a national asthma strategy. The Global Asthma Network (GAN) was established in 2012, a collaboration between individuals from ISAAC and the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease (The Union). Its goals are to improve asthma care globally, with a focus on LMICs,20 through enhanced surveillance, research collaboration, capacity building and access to quality-assured essential medicines. Given the large number of centres and countries involved with GAN, it was well placed to undertake such a survey.

Based on the low number of national asthma strategies reported in the literature, our hypothesis was that most countries in the world do not have a national asthma strategy. GAN has collaborators in more than half of the world's countries, which enabled a simple survey to be undertaken to answer a question about whether a country had a national asthma strategy for children and adults.

Materials and methodsA cross-sectional survey of GAN centres was carried out between April 2013 and July 2014. A GAN centre was one where an Expression of Interest form had been submitted to the GAN Global Centre (Auckland). The survey was sent by email to each centre's principal investigator by the GAN Research Manager (PE). The survey was sent to GAN Principal Investigators in 276 centres in 120 countries; 46 were HICs and 74 LMICs, defined by the criteria used by the World Bank for the period 1 July 2013–30 June 2014.21

The survey form had eight questions, the last one of which was “Has a national asthma strategy been developed in your country for the next five years? For children? (Yes/No/Don’t Know), For adults? (Yes/No/Don’t Know)”. The former seven questions were about national asthma management guidelines in their country (not included in these analyses).

Where conflicting answers were given by two or more investigators from different centres within a country, the GAN Global Centre staff entered into a discussion via email with the centre investigators until agreement between them was reached.

Country findings were compared with the prevalence of asthma symptoms in 13–14 year olds in countries where this had been estimated in ISAAC Phase Three.22 Countries were categorised as high prevalence if the prevalence of current wheeze was >20%, and low prevalence if the prevalence of current wheeze was <10%. The relationship of national asthma strategies to changes in country prevalence of asthma symptoms in 13–14 year olds in countries where this had been estimated in ISAAC Phase Three4 was also examined.

The data were entered into an Excel spreadsheet and checked for apparent inconsistencies which were reconciled if appropriate. Simple descriptive analyses were undertaken. The Chi-Squared test was used to compare responses about strategies between LMICs and HICs, and high and low prevalence countries with those answering ‘Yes’ compared with those not answering Yes (‘No’ or ‘Don’t know’).23

ResultsOf the 276 centre principal investigators in 120 countries, 213 (77.2%) investigators in 112 (93.3%) countries completed the national asthma strategy question. There were no responses from any investigators in eight countries who were approached: three HICs and five LMICs.

Conflicting answers were obtained from two or more centres in 16 countries, and agreement was subsequently reached. Of the 112 countries, 43 (38.4%) were HICs including 48.3% of the world's 89 HICs; 69 (61.6%) were LMICs including 48.2% of the world's 143 LMICs (Table 1).

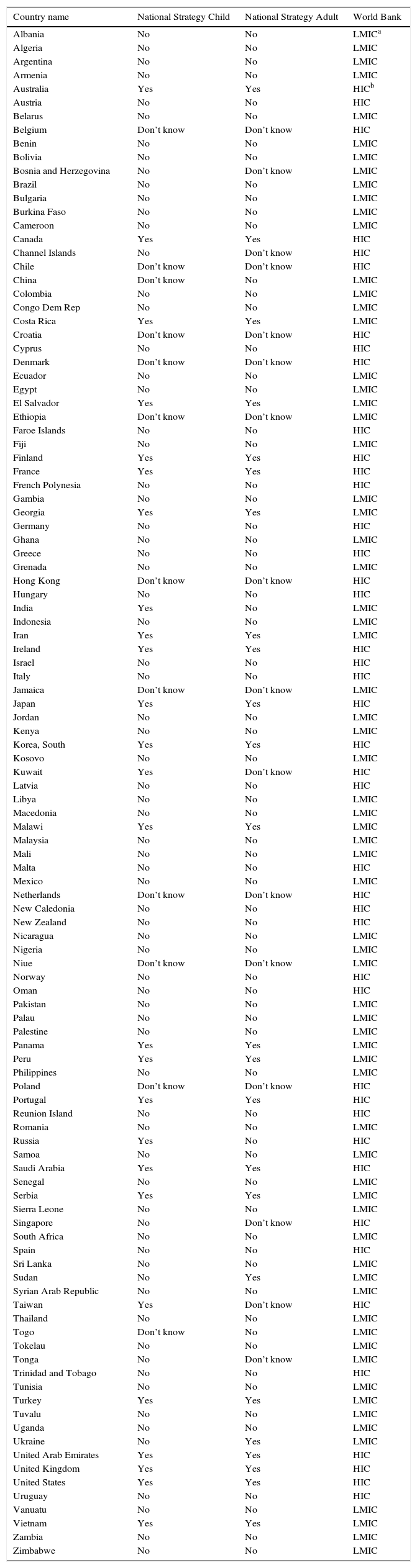

Responses to national asthma strategy questions by country, age group and country income.

| Country name | National Strategy Child | National Strategy Adult | World Bank |

|---|---|---|---|

| Albania | No | No | LMICa |

| Algeria | No | No | LMIC |

| Argentina | No | No | LMIC |

| Armenia | No | No | LMIC |

| Australia | Yes | Yes | HICb |

| Austria | No | No | HIC |

| Belarus | No | No | LMIC |

| Belgium | Don’t know | Don’t know | HIC |

| Benin | No | No | LMIC |

| Bolivia | No | No | LMIC |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | No | Don’t know | LMIC |

| Brazil | No | No | LMIC |

| Bulgaria | No | No | LMIC |

| Burkina Faso | No | No | LMIC |

| Cameroon | No | No | LMIC |

| Canada | Yes | Yes | HIC |

| Channel Islands | No | Don’t know | HIC |

| Chile | Don’t know | Don’t know | HIC |

| China | Don’t know | No | LMIC |

| Colombia | No | No | LMIC |

| Congo Dem Rep | No | No | LMIC |

| Costa Rica | Yes | Yes | LMIC |

| Croatia | Don’t know | Don’t know | HIC |

| Cyprus | No | No | HIC |

| Denmark | Don’t know | Don’t know | HIC |

| Ecuador | No | No | LMIC |

| Egypt | No | No | LMIC |

| El Salvador | Yes | Yes | LMIC |

| Ethiopia | Don’t know | Don’t know | LMIC |

| Faroe Islands | No | No | HIC |

| Fiji | No | No | LMIC |

| Finland | Yes | Yes | HIC |

| France | Yes | Yes | HIC |

| French Polynesia | No | No | HIC |

| Gambia | No | No | LMIC |

| Georgia | Yes | Yes | LMIC |

| Germany | No | No | HIC |

| Ghana | No | No | LMIC |

| Greece | No | No | HIC |

| Grenada | No | No | LMIC |

| Hong Kong | Don’t know | Don’t know | HIC |

| Hungary | No | No | HIC |

| India | Yes | No | LMIC |

| Indonesia | No | No | LMIC |

| Iran | Yes | Yes | LMIC |

| Ireland | Yes | Yes | HIC |

| Israel | No | No | HIC |

| Italy | No | No | HIC |

| Jamaica | Don’t know | Don’t know | LMIC |

| Japan | Yes | Yes | HIC |

| Jordan | No | No | LMIC |

| Kenya | No | No | LMIC |

| Korea, South | Yes | Yes | HIC |

| Kosovo | No | No | LMIC |

| Kuwait | Yes | Don’t know | HIC |

| Latvia | No | No | HIC |

| Libya | No | No | LMIC |

| Macedonia | No | No | LMIC |

| Malawi | Yes | Yes | LMIC |

| Malaysia | No | No | LMIC |

| Mali | No | No | LMIC |

| Malta | No | No | HIC |

| Mexico | No | No | LMIC |

| Netherlands | Don’t know | Don’t know | HIC |

| New Caledonia | No | No | HIC |

| New Zealand | No | No | HIC |

| Nicaragua | No | No | LMIC |

| Nigeria | No | No | LMIC |

| Niue | Don’t know | Don’t know | LMIC |

| Norway | No | No | HIC |

| Oman | No | No | HIC |

| Pakistan | No | No | LMIC |

| Palau | No | No | LMIC |

| Palestine | No | No | LMIC |

| Panama | Yes | Yes | LMIC |

| Peru | Yes | Yes | LMIC |

| Philippines | No | No | LMIC |

| Poland | Don’t know | Don’t know | HIC |

| Portugal | Yes | Yes | HIC |

| Reunion Island | No | No | HIC |

| Romania | No | No | LMIC |

| Russia | Yes | No | HIC |

| Samoa | No | No | LMIC |

| Saudi Arabia | Yes | Yes | HIC |

| Senegal | No | No | LMIC |

| Serbia | Yes | Yes | LMIC |

| Sierra Leone | No | No | LMIC |

| Singapore | No | Don’t know | HIC |

| South Africa | No | No | LMIC |

| Spain | No | No | HIC |

| Sri Lanka | No | No | LMIC |

| Sudan | No | Yes | LMIC |

| Syrian Arab Republic | No | No | LMIC |

| Taiwan | Yes | Don’t know | HIC |

| Thailand | No | No | LMIC |

| Togo | Don’t know | No | LMIC |

| Tokelau | No | No | LMIC |

| Tonga | No | Don’t know | LMIC |

| Trinidad and Tobago | No | No | HIC |

| Tunisia | No | No | LMIC |

| Turkey | Yes | Yes | LMIC |

| Tuvalu | No | No | LMIC |

| Uganda | No | No | LMIC |

| Ukraine | No | Yes | LMIC |

| United Arab Emirates | Yes | Yes | HIC |

| United Kingdom | Yes | Yes | HIC |

| United States | Yes | Yes | HIC |

| Uruguay | No | No | HIC |

| Vanuatu | No | No | LMIC |

| Vietnam | Yes | Yes | LMIC |

| Zambia | No | No | LMIC |

| Zimbabwe | No | No | LMIC |

Of those 112 countries where the national asthma strategy questions were answered for children, 12 reported ‘Don’t Know’, seven in HICs and five in LMICs. For adults, 16 reported ‘Don’t Know’, 11 in HICs and five in LMICs.

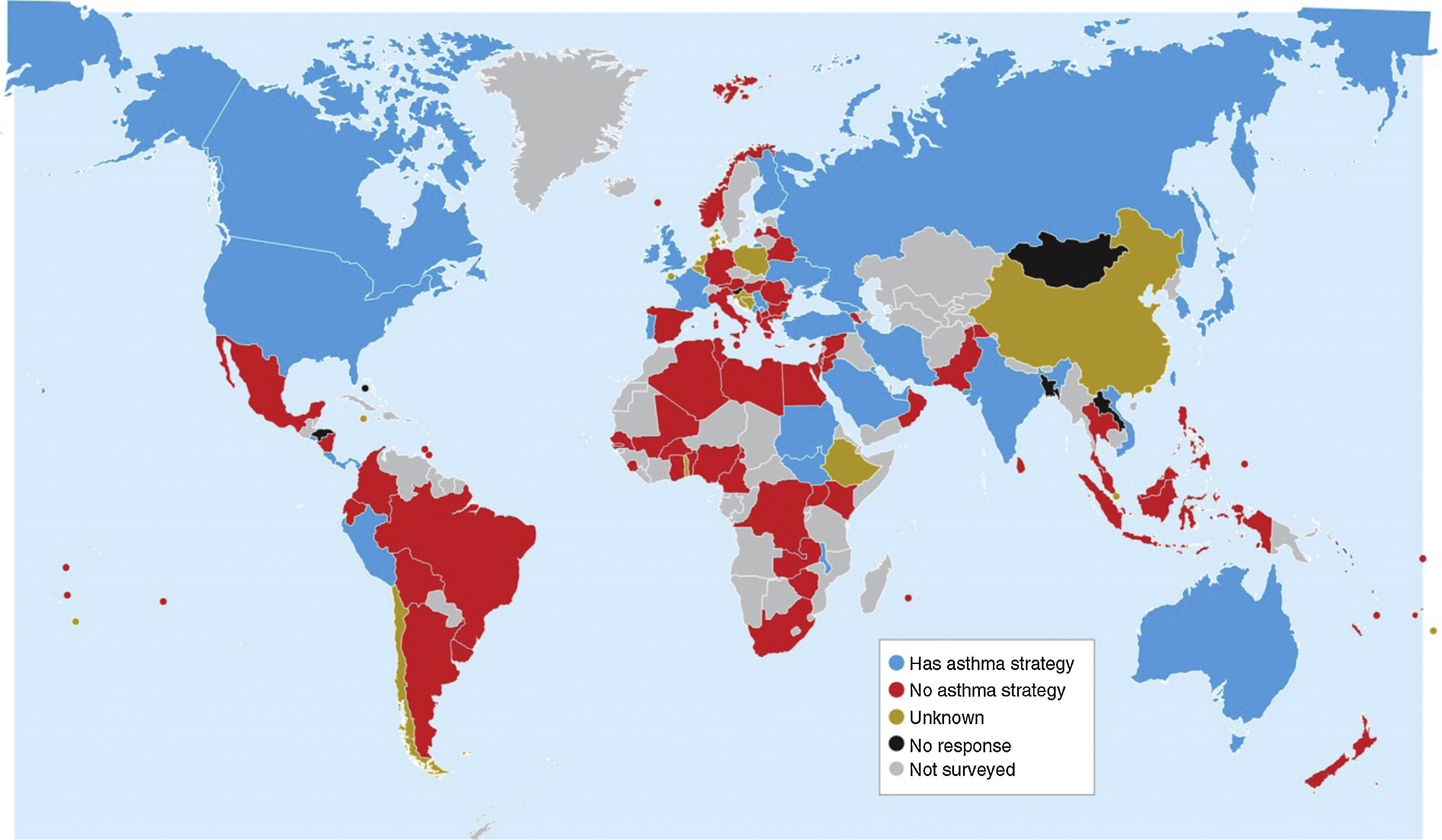

Of the 112 countries, 26 (23.2%) reported a national asthma strategy for children, 24 (21.4%) reported a national asthma strategy for adults, and 22 (19.6%) countries had strategies for both children and adults. Twenty-eight (25%) had a national asthma strategy for at least one age group. These are illustrated in Fig. 1.

Of the 28 countries who reported a national asthma strategy for at least one age group 15 (53.6%) were HICs and 13 (46.4%) LMICs. Strategies were reported in 15/43 (34.9%) HICs and 13/69 (18.8%) LMICs; these differences were not significant p=0.057.

In 81/112 (72%) countries the prevalence of asthma symptoms had been estimated in ISAAC. Any national asthma strategy was significantly more common in countries with high prevalence of current wheeze (>20%) than low prevalence (<10%): 11/13 (85%) and 7/31 (22.6%) respectively, p<0.001, with the remaining 37 countries having prevalence 10–20%. Of the 49 countries in whom time-trends in the prevalence of asthma symptoms had been estimated in ISAAC, any national asthma strategy was equally common in those whose prevalence rose (11/30) and in those in which it fell (6/19) p=0.72.

DiscussionIn this email survey of about half the world's countries GAN was able to confirm our hypothesis that most countries in the world do not have a national asthma strategy; only about one in four countries reported that they had a national asthma strategy. Of potential concern was that the proportion of LMICs with a strategy was lower than HICs, although this was not statistically significant.

About three in four countries surveyed by GAN had the prevalence of asthma symptoms measured in ISAAC, and of these, having a national asthma strategy was significantly more common in countries with high prevalence compared with low prevalence of current wheeze. While on the face of it this seems logical – more asthma symptoms, more concern to take action to address the issue – there are three caveats. Firstly, many of the countries with a low prevalence of asthma symptoms and no national asthma strategy have very large populations; e.g. Brazil, China, Indonesia, Mexico, Philippines, each of which has >100 million people and is among the top 12 most populous countries in the world in 2015.24 Small improvements in the management and outcomes for people with asthma in each of these countries would have a relatively big impact on the global numbers of people burdened by asthma. Secondly, in this survey one in four countries had not measured their asthma prevalence, which illustrates either their lack of interest in asthma or perhaps they had experienced difficulties engaging in world-wide epidemiological studies. Thirdly, the ISAAC data is already 13 years old (2002–3) and thus not coincident with this survey, so the interpretation needs caution.

This is a very large study, a high response rate of 93% was achieved, data was reported from 112 countries, and the countries which responded were about half the world's HICs and LMICs. The response rate was high because of the close relationship between the GAN Global Centre and GAN Principal Investigators.

The recommended components of a successful national asthma strategy include: government commitment, policies and legislation (e.g. tobacco reduction), management by the health ministry, funding and capacity building, registry of outcome data before and after implementation (prevalence, severity, asthma control, hospitalisations, mortality), asthma management guidelines adjusted for the country, access to medical care and quality-assured, affordable, essential asthma medicines available for everyone with asthma, education of the public, continued education of health professionals, economic analyses, process and outcome evaluation, follow-up programmes, and continued asthma research.5,9

There may be different interpretations of the term ‘national asthma strategy’ which is also synonymous with the term ‘national asthma programme’. National asthma management guidelines alone should not be considered a national asthma strategy or programme, although they form an essential part. In this particular survey, national asthma management guidelines alone were unlikely to be confused with strategy, because they were asked about in the preceding seven questions in the survey. However, the survey is likely to have missed asthma strategies which were not country-wide; these would be more likely in a very large country like Brazil or China. Additionally, some national asthma ‘programmes’ may not have been interpreted as ‘strategies’ for the purpose of this survey.

In the review of national and regional asthma strategies in Europe,9 a systematic search of the English literature in 2014 found only eight published national and regional asthma strategies in European Union countries: Finland,7 France, Ireland, Italy, The Netherlands, Lodz area of Poland, whole of Poland and Portugal,11 with only three strategies having been evaluated (Finland, Poland, Portugal). Outside the European Union, asthma strategies have been identified from only eight other countries.13–19,25

There are likely to be many reasons for the low level of publication of national asthma strategies where they exist, including poor preparation with insufficient documentation, dissemination, implementation or evaluation, lack of appropriate training of primary health care professionals in diagnosis and treatment, poor access to quality-assured, essential asthma medicines, poor outcomes, unable to prepare an article for publication in English, and publication bias. The absence of a national asthma strategy may reflect that asthma is not recognised as a serious public health problem, a lack of asthma prevalence, severity and mortality data, a lack of government prioritisation of asthma among other non-communicable diseases, lack of national health coordination, and/or a lack of government commitment to improving national health issues.

Not all national asthma strategies have been successful. Selroos and others have suggested that good results can also be achieved without a formal national asthma strategy, as long as evidence-based management guidelines are implemented and widely used.9 This is happening, for example, in Sweden, where recommendations (in Swedish) for diagnosis and treatment have been issued and updated by the National Board of Health and Welfare.26 The Swedish Asthma and Allergy Foundation has recently issued a comprehensive national strategy document. It has been estimated that global asthma deaths (all ages) reduced from 504,300 in 1990 to 489,000 in 2013,27 but many countries do not report asthma deaths separately.28 In Europe, asthma mortality decreased from 6441 to 1164 cases (82%) from 1990–2012.29

In 2009, a group of experts in asthma care, the Advancing Asthma Care Network, reviewed asthma projects and strategies in Argentina, Australia, Brazil, China, Japan, Mexico, Philippines, Russia, South Africa, and Turkey.30 All successful asthma strategies improved early diagnosis and the introduction of first-line treatment with anti-inflammatory medication, improved long-term disease control nationally, introduced simple means for guided self-management to proactively prevent exacerbations/attacks, and had effective education and networking with general practitioners, nurses and pharmacists. A systematic approach was recommended, aiming to motivate and organise, and with improvements that could be achieved with relatively simple means. When multidisciplinary actions are being planned, all the main stakeholders should be represented.

A more limited approach to improving asthma outcomes has been used successfully in pilot projects in LMICs, using ‘standard case management’, a term which “encompasses diagnosis of asthma, standardisation of treatment according to severity based on asthma guidelines, and patient education, coupled with a simple system for monitoring patient outcomes. Appropriate training of health care workers and availability of essential asthma medicines are key to the effectiveness of standard case management.”.31 Pilot studies in 2007–2008 of the feasibility and effects of standard case management were applied in Benin,32 Haiyuan County, Anhui Province, China,33 and Sudan34 reduced hospitalisations in those completing the study. In El Salvador 2005–2010,35 by using Practical Approach to Lung Health and essential asthma medicines free of charge, the number of patients being referred from primary to secondary or tertiary level dropped by 60%, with greater convenience for patients, and savings for health services.

Political engagement, leadership and commitment are key components for developing an effective national asthma strategy, and these are challenging and may not be easily achieved. The literature supports the view that programmes (strategies) are more likely to be successful where this has occurred. The political organisation and health leadership in a country would undoubtedly influence the chance of success, as would co-ordinated access to affordable, quality-assured, essential asthma medicines. Identifying a political champion is a critical factor, and may be easier in some localities than others. In 2010 the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) launched a challenge to countries to reduce hospitalisations by 50% over five years36 but the results have been modest. The motivation to tackle the asthma burden is not always self-evident, e.g. in places where private health-care dominates and hospitals compete.

In this survey, we asked only about national asthma strategies, not local or regional strategies. We know that there have been successful strategies in cities such as Salvador, Brazil14; although these would not have been identified in our survey. Strategies at a sub-national level may be the only feasible approach in some very large and populous countries such as Brazil and China; in such cases, coverage of the whole nation by harmonised sub-national strategies would be sought.

The survey asked about national asthma strategies for children separately from adults. Most who reported strategies had them for both age groups. The reasons why there would be separate strategies may include different approaches between children and adults, as often happens with national asthma management guidelines. Or there may have been ascertainment bias, with child-health professionals not being aware that an asthma strategy had been developed for adults and vice versa.

A successful strategy is not expected to affect prevalence and incidence as we do not have effective interventions for these.20 However, reduction in disease severity and improved control may be impressive. In Finland in early 1990s, 20% of patients were estimated to have uncontrolled (severe) asthma compared to 10% in 2001 and 4% in 2010.7,37 If the gains of the Finnish study were replicated by having effective national asthma strategies throughout the world, then the number of emergency visits would be estimated to fall by 24% in adults and 61% in children, hospital days would fall by about 54%, significant disability would decrease by about 76%, costs per patient per year would fall by 36%, and deaths by 31%. Even if half these gains were achieved, there would be a large reduction of the burden of asthma in the world. Implementation of a national strategy is an appropriate way to address asthma, where the disability numbers and costs are disproportionately high, in contrast with the relatively high mortality found with other non-communicable diseases.20

We recommend that health authorities along with governments in all countries should develop national asthma strategies with associated national action plans to improve early detection of asthma and subsequently improve asthma management and reduce costs.5 Such strategies should be evaluated, reported, and published. The problems to be addressed may be different in HICs compared to LMICs, and the solutions need to be tailored according to an individual country's local needs, resources and organisation. Knowledge of asthma prevalence and severity and changes over time is fundamental to understanding the burden of asthma within each country and thus leading to the development of a national asthma strategy. This can be achieved using the methodology developed by ISAAC38,39 and continued (expanded to include adults) under GAN.40

Ethical disclosuresConfidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.

Protection of human subjects and animals in researchThe authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the responsible Clinical Research Ethics Committee and in accordance with those of the World Medical Association and the Helsinki Declaration.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest. The corresponding author confirms that she had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

The authors wish to acknowledge the funder, The International Union against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, for grants to the Global Asthma Network 2013–2015.

I Asher – University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand; NE Billo, Joensuu, Finland; K Bissell – International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease (The Union), Paris, France; C-Y Chiang – International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease (The Union), Taipei City, Taiwan; A El Sony – The Epidemiological Laboratory for Public Health and Research, Khartoum, Sudan; P Ellwood – University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand; L García-Marcos – ‘Virgen de la Arrixaca’ University Children's Hospital, Murcia, Spain; J Mallol – University of Santiago de Chile (USACH), Santiago, Chile; GB Marks – University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia; N Pearce – London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, United Kingdom; D Strachan – St George's, University of London, London, United Kingdom.

Albania: A Priftanji – Mother Theresa University Hospital of Tirana (Tiranë); Algeria: B Benhabylès – CHU Mustapha (Wilaya of Algiers), R Boukari – Saad Dahlab University (Blida); Argentina: FA Castracane – Programa Provincial Asma Infantil de Mendoza (Mendoza), M Gómez – Hospital San Bernardo (Salta), N Salmun – Asthma and Allergy Foundation (Buenos Aires); Armenia: A Baghdasaryan – “Arabkir” Joint Medical Centre (Yerevan); Australia: S Burgess – Mater Children's Hospital (Brisbane), GB Marks – University of New South Wales (Sydney), J Mattes – Hunter Medical Research Institute and Newcastle Children's Hospital (Newcastle), A Tai – Adelaide University (Adelaide); Austria: G Haidinger – Medical University Vienna (Urfahr-umgebung), J Riedler – Children's Hospital Schwarzach (Salzburg); Belarus: A Shpakou – Yanka Kupala State University of Grodno (Grodno); Belgium: J Weyler – University of Antwerp (Antwerp); Benin: M Gninafon – Université d’Abomey-Calavi (Cotonou); Bolivia: J Aguirre de Abruzzese – Department of Health (Santa Cruz); Bosnia and Herzegovina: S Domuz – School of Applied Health Sciences (Prijedor); Brazil: HV Brandão – Universidade Estadual de Feira de Santana (Feira de Santana), PAM Camargos – Federal University of Minas Gerais (Belo Horizonte), M de Britto – Instituto de Medicina Integral (Recife), GB Fischer – Universidad Federal (Porto Alegre), FC Kuschnir – Rio de Janeiro State University (UERJ) (Rio de Janeiro), AM Menezes – Federal University of Pelotas (Pelotas), AC Porto Neto – Passo Fundo University (Passo Fundo), N Rosário – University of Parana (Curitiba), D Solé – Universidade Federal de São Paulo (São Paulo South), NF Wandalsen – Faculdade de Medicina do ABC (Santo André); Bulgaria: TB Mustakov – University Hospital ‘Alexandrovska’, Medical University (Sofia); Burkina Faso: E Birba – Université Poly Technique – BOBO (Bobo-Dioulasso); Cameroon: BH Mbatchou Ngahane – University of Douala (Douala), EW Pefura Yone – Yaounde Jamot Hospital (Bafoussam); Canada: DC Rennie – University of Saskatchewan (Saskatoon), T To – University of Toronto, (Ontario); Channel Islands: P Standring – Princess Elizabeth Hospital (Guernsey); Chile: MA Calvo Gil – Universidad Austral de Chile (Valdivia); China: Y-Z Chen – Training Hospital for Peking University (Beijing), X Kan – Anhui Chest Hospital (Hefei), Y Lin – The Union (Tayuan); Colombia: E Garcia – Fundación Santa Fe de Bogotá (Bogotá), J Niederbacher – Universidad Industrial de Santander (Bucaramanga), GA Ordoñez – Universidad Libre de Cali (Cali); Congo, Dem. Rep.: B Kabengele Obel – University of Kinshasa (Kinshasa); Costa Rica: ME Soto-Quirós – University of Costa Rica (Costa Rica); Croatia: S Banac – Rijeka Clinical Hospital Centre (Rijeka); Cyprus: P Yiallouros – Cyprus International Institute for Environmental & Public Health (Nicosia); Denmark: L Lochte – University of Copenhagen (Copenhagen); Ecuador: S Barba – AXXIS-Medical Centre SEAICA (Quito), P Cooper – Universidad San Francisco de Quito (Esmeraldas); Egypt: M El Falaki – Cairo University (Cairo), A Mokhtar – Ministry of Health (Alexandria); El Salvador: M Figueroa Colorado – Universidad Dr Jose Matias Delgado (San Salvador); Ethiopia: A Berihu – Health Consultancy Centre (Mekelle); Faroe Islands: P Weihe – The Faroese Hospital System (Faroe Islands); Fiji: VA Lal – Ministry of Health (Suva); Finland: M Mäkelä – Helsinki University Hospital (Helsinki); France: I Annesi-Maesano – Medical School Saint-Antoine, France (West Marne, Créteil), D Charpin – Aix Marseille University (Marseille), C Raherison – University of Bordeaux (Bordeaux); French Polynesia: I Annesi-Maesano – Medical School Saint-Antoine, France (Polynésie française); Georgia: M Gotua – Center of Allergy & Immunology (Tbilisi, Kutaisi); Germany: E von Mutius – Ludwig Maximilians University (Munich); Ghana: EO Addo-Yobo – Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital (KATH) (Kumasi), NF Clement – FHI 360 Ghana Country Office (Accra); Greece: Ch Gratziou – National Kapodistrian University of Athens (Athens), J Tsanakas – University of Thessaloniki (Thessaloniki); Grenada: M Akpinar-Elci – Old Dominion University (Grenada); Hong Kong: CKW Lai – The Chinese University of Hong Kong (Hong Kong); Hungary: Z Novák – University of Szeged (Szeged); India: S Awasthi – King George's Medical University (Lucknow), R Ilangho – Apollo Hospitals (Chennai), A Maitra – Institute of Child Health (Kolkata (10)), M Mukherjee – KPC Medical College and Hospital (Kolkata (14)), UA Pai – Consultant Pediatrician (Mumbai (7)), AV Pherwani – P.D. Hinduja Hospital and Medical Research Centre (Mumbai (11)), BK Reddy – Indira Gandhi Institute of Child Health (Bangalore), M Sabir – Maharaja Agrasen Medical College (Bikaner), SK Sharma – All India Institute of Medical Sciences (New Delhi), V Singh – Asthma Bhawan (Jaipur), M Singh – Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research (Chandigarh), TU Sukumaran – Pushpagiri Medical College (Kottayam), S Varkki – Christian Medical College Hospital (Vellore); Indonesia: CB Kartasasmita – Padjajaran University (Bandung); Iran: M Cheraghi – Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences (Ahvaz), M Karimi – Shahid Sadoughi Medical University (Yazd), M-R Masjedi – National Research Institute of Tuberculosis and Lung Diseases (Birjand, Bushehr, Rasht, Tehran, Zanjan); Ireland: P Manning – Royal College of Surgeons Medical School (Ireland); Israel: T Shohat – Israel Center for Disease Control (Israel); Italy: S Bonini – Via Ugo de Carolis 59 (Ascoli Piceno), F Forastiere – Rome E Health Authority (Roma), S La Grutta – Institute of Biomedicine and Molecular Immunology (Palermo), MG Petronio – Local Health Authority (Empoli), S Piffer – Azienda Provinciale per I Servizi Sanitari (Trento); Jamaica: E Kahwa – University of the West Indies (Kingston); Japan: H Odajima – National Hospital Organization Fukuoka Hospital (Fukuoka), S Yoshihara – Dokkyo Medical University (Tochigi); Jordan: F Abu-Ekteish – Jordon University of Science and Technology (Amman), O Al Omari – Jerash University (Jerash); Kenya: EI Amukoye – Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) (Nairobi), FO Esamai – Moi University College of Health Sciences (Eldoret); Korea, South: S-J Hong – University of Ulsan (Seoul); Kosovo: L Neziri-Ahmetaj – University Hospital (Prishtina); Kuwait: JA al-Momen – Al-Amiri Hospital (Kuwait); Latvia: V Svabe – Riga Stradins University (Riga); Libya: M Shenkada – Ministry of Health (Tripoli); Macedonia: E Vlaski – University Children's Clinic (Skopje); Malawi: K Mortimer – Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine (Blantyre); Malaysia: J de Bruyne – University of Malaya (Klang Valley); Mali: Y Toloba – Université de Bamako (Bamako); Malta: S Montefort – University of Malta (Malta); Mexico: BE Del-Río-Navarro – Hospital Infantil de México (Mexico City North), R García-Almaráz – Hospital Infantil de Tamaulipas (Ciudad Victoria), SN González-Díaz – Hospital Universitario (Monterrey), DD Hernández-Colín – Hospital Civil De Guadalajara Juan I Menchaca (Guadalajara), CA Jiménez González – Universidad Autonoma of San Luis Potosí (San Luis Potosí), JV Mérida-Palacio – Centro de Investigacion de Enfermedades Alergicas y Respiratorias (Mexicali); Netherlands: B Brunekreef – Universiteit Utrecht (Utrecht); New Caledonia: I Annesi-Maesano – Medical School Saint-Antoine, France (Nouvelle-Calédonie); New Zealand: I Asher – University of Auckland (Auckland), S Currie – Hawke's Bay District Health Board (Hawke's Bay), J Douwes – Massey University (Wellington), D Graham – Waikato District Health Board (Waikato), R Hancox – University of Otago (Otago), C Moyes – Whakatane Hospital (Bay of Plenty), P Pattemore – University of Otago, Christchurch (Christchurch); Nicaragua: MZ Cordero Rizo – University National Autonomous of Nicaragua (Matagalpa); Nigeria: GE Erhabor – Obafemi Awolowo University (Ife), A Falade – University of Ibadan (Ibadan), B Garba Ilah – Ahmad Sani Yariman Bakura Specialist Hospital (Gusau), A Hammangabdo – University of Maiduguri Teaching Hospital (Maiduguri), N Onyia – Paelon Memorial Clinic (Lagos); Niue: M Pulu – Niue Foou Hosptial (Niue Island); Norway: W Nystad – Norwegian Institute of Public Health (Oslo, Tromsø); Oman: O Al-Rawas – Sultan Qaboos University (Al-Khod); Pakistan: MO Yusuf – The Allergy & Asthma Institute (Islamabad); Palau: BM Watson – Ministry of Health (Republic of Palau); Palestine: N El Sharif – Al Quds University (North Gaza, Ramallah); Panama: G Cukier – Hospital Materno Infantil Jose Domingo de Obaldia (David-Panamá); Peru: W Checkley – Johns Hopkins University (Tumbes, Puno), P Chiarella – Universidad Peruana de Ciencias Aplicadas, UPC (Lima); Philippines: R Pagcatipunan – Adventist Medical Center Manila (Metro Manila); Poland: G Lis – Jagiellonian University (Kraków); Portugal: M Morais-Almeida – Hospital CUR Descobertas (Lisboa); Reunion Island: I Annesi-Maesano – Medical School Saint-Antoine, France (Reunion Island); Romania: D Deleanu – University of Medicine & Pharmacy IULIU Hatieganu (Cluj-Napoca); Russia: E Kamaltynova – The Siberian State Medical University (Tomsk), EG Kondiurina – Novosibirsk State Medical University (Novosibirsk); Samoa: L Esera-Tulifau – Moto’otua Hospital/National Health Services (Apia); Saudi Arabia: BR Al-Ghamdi – King Khaled University (Abha), A Yousef – University of Dammam/King Fahd Hospital of the University (Alkhobar); Senegal: NO Toure – Université Cheikh Anta DIOP, (Dakar); Serbia: M Hadnadjev – Primary Health Care (Novi Sad), D Višnjevac – The Health Centre of Indjija (Indjija), Z Zivkovic – Children's Hospital for Lung Diseases and Tuberculosis (Belgrade); Sierra Leone: G Fadlu-Deen – Connaught Teaching Hospital (Freetown); Singapore: DYT Goh – National University of Singapore (Singapore); South Africa: R Masekala – University of Pretoria (Pretoria), K Voyi – University of Pretoria (Polokwane, Ekurhuleni), HJ Zar – University of Cape Town (Cape Town); Spain: A Arnedo-Pena – Center Public Health Castellon (Castellón), RM Busquets – Universidad Autonoma de Barcelona (Barcelona), I Carvajal-Urueña – Centro de Salud de La Ería (Asturias), L García-Marcos – ‘Virgen de la Arrixaca’ University Children's Hospital (Cartagena), C González Díaz – Universidad del País Vasco UPV/EHU (Bilbao), J Korta Murua – Donostia Hospital (San Sebastián), A López-Silvarrey Varela – Fundacion Maria Jose Jove (La Coruña), C Luna-Paredes – Sección de Neumología y Alergia Infantil (Madrid), M Morales-Suárez-Varela – Valencia University-CIBERESP (Valencia), M Praena-Crespo – Servicio Andaluz de Salud (Sevilla), A Rabadán-Asensio – Delegation at Cadiz of Andalusian Regional Health Ministry (Cádiz), J Wärnberg – University of Málaga (Málaga); Sri Lanka: KD Gunasekera – Central Chest Clinic Colombo (Colombo), ST Kudagammana – Teaching Hospital Peradeniya (Peradeniya); Sudan: A El Sony – The Epidemiological Laboratory for Public Health and Research (Khartoum), S Hassanain – Ministry of Health (Gadarif); Syrian Arab Republic: Y Mohammad – National Center for Research and Training in Chronic Respiratory Diseases – Tishreen University (Lattakia); Taiwan: YL Guo – National Taiwan University (Tainan), J-L Huang – Chang Gung University (Taipei); Thailand: M Lao-araya – Chiang Mai University (Chiang Mai), S Phumethum – Prapokklao Hospital (Chantaburi), J Teeratakulpisarn – Khon Kaen University (Khon Kaen), P Vichyanond – Mahidol University (Bangkok); The Gambia: S Anderson – Medical Research Council Unit (Fajara); Togo: O Tidjani – CHU Tokoin (Lome); Tokelau: T Iosefa – Ministry of Health (Tokelau); Tonga: G Aho – Vaiola Hospital (Nuku’alofa); Trinidad and Tobago: D Dookeeram – Sangre Grande Hospital (Trinidad and Tobago); Tunisia: A Hamzaoui – Abderrahmen Mami Hospital (Ariana); Turkey: A Yorgancioğlu – Celal Bayar University School of Medicine (Ankara); Tuvalu: N Ituaso-Conway – Princess Margaret Hospital (Funafuti); Uganda: W Worodria – Mulago Hospital & Complex (Kampala); Ukraine: O Fedortsiv – Ivan Horbachevsky Ternopil State Medical University (Ternopil); United Arab Emirates: B Mahboub – University of Sharjah (Sharjah); United Kingdom: AH Mansur – University of Birmingham and Heartlands Hospital (Birmingham); United States: M Akpinar-Elci – Old Dominion University (Virginia), RP Doshi – Parkview Hospital (Fort Wayne), GJ Redding – Seattle Children's Hospital (Seattle), K Yeatts – University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (North Carolina); Uruguay: M Valentin-Rostan – Hospital Pereira Rossell (Montevideo); Vanuatu: G Harrison – Vila Central Hospital (Port Vila); Vietnam: LTT Le – University Medical Centre (Ho Chi Minh); Zambia: S Wa Somwe – University Teaching Hospital (Lusaka); Zimbabwe: P Manangazira – Ministry of Health and Child Care (Zimbabwe).