The fraction of exhaled nitric oxide (FENO) measured using portable devices is increasingly used in the clinical setting to assess asthmatic children. However, there is little and variable information on the reference values obtained using these devices in healthy children from different populations.

Methods190 healthy non-smoker children (8–15 years old) were randomly selected from public schools participating in this study. The objective was to determine FENO reference values for healthy Chilean schoolchildren. Healthy individuals were identified by medical interview and parent questionnaire on the use of asthma medications, and current and past symptoms of asthma, rhinoconjunctivitis and eczema. FENO was measured at schools using a portable device with electrochemical sensor (NIO MINOX). Reference values of FENO were expressed as geometric mean and upper limit of the 95% reference interval (right-sided). The relationship of FENO with gender, age, height, body mass, and other factors was assessed by multiple regression, and the difference between groups was contrasted by ANOVA.

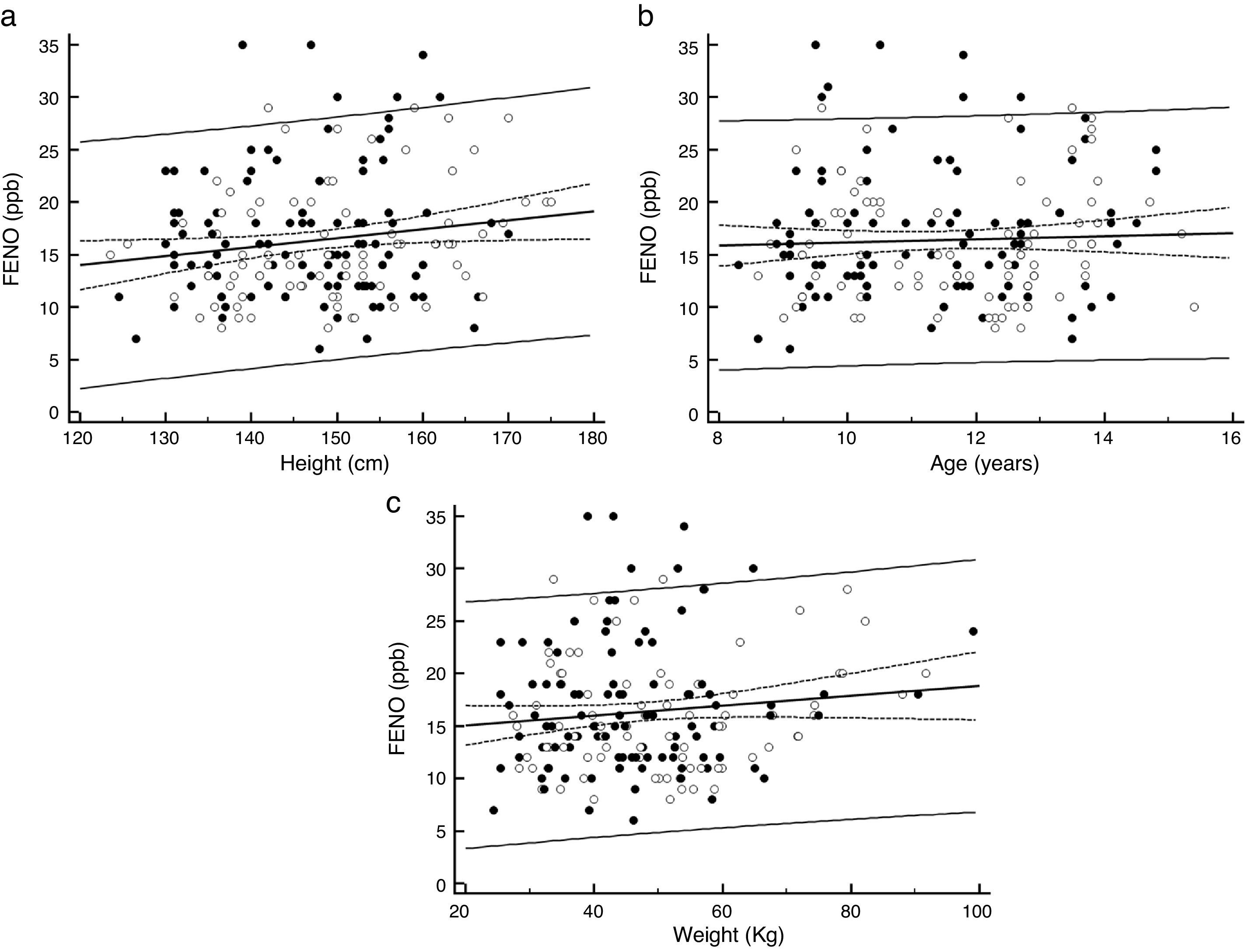

ResultsThe FENO geometric mean was 15.4ppb with a 95% reference interval upper limit (right-sided), of 27.4ppb (90%CI 25.6–29.2). The 5th and 95th percentiles were 9.0ppb and 28.0ppb, respectively. Height was the only factor significantly associated to FENO (p=0.022). There was no significant difference in mean FENO regarding age, gender, weight, parent reported rhinoconjunctivitis and eczema.

ConclusionThis study suggests that FENO values higher than 27ppb are likely to be abnormal and would reflect airway inflammation in children as those in the present study.

The fraction of nitric oxide in the exhaled air (FENO) is recognised as a reliable marker of eosinophilic airway inflammation and responsiveness to corticosteroids in asthmatic patients.1 It adds complementary information for asthma management to that obtained by conventional clinical and lung function measurements,1–5 and because it is a portable, non-invasive, reproducible and easy-to-perform test, it represents an attractive option for assessing FENO in asthmatic children in the clinical setting.6 However, there are relatively few reports on FENO values in healthy schoolchildren measured with a portable device using electrochemical sensors.2 Furthermore, the available information on FENO reference values shows important variability that would be determined by several factors as age, height, gender, atopy, environmental exposures, ethnic characteristics, among others, but also because of the difference in methodologies to select healthy individuals, FENO measuring devices, and ways of expressing results (geometric mean, median, range, upper limit, percentiles, among others).2,3 The above-mentioned variability may be an issue for physicians when deciding on choosing a set of reference values for their paediatric asthmatic patients in the clinical setting.

The ATS clinical practice guideline for the interpretation of FENO levels1 has recommended lower and upper limits of FENO in children; i.e., <20ppb in children would unlikely be related with eosinophilic inflammation and responsiveness to corticosteroids. On the contrary, FENO >35ppb would indicate eosinophilic inflammation and probable response to inhaled corticosteroids. However, there is as yet no information as to whether those threshold values are applicable to healthy children from different populations, mainly because these limits may vary according to different factors inherent to patients and their environments.2–5

To the best of our knowledge, there is no published data on reference values of FENO in healthy schoolchildren from Latin America. This study was undertaken to determine the reference values of FENO in healthy Chilean schoolchildren, measured on-line using a portable device with an electrochemical sensor.

Materials and methodsOne-hundred and ninety healthy schoolchildren (8–15 years old) from public schools in southern Santiago de Chile participated in this study. Healthy children were defined as subjects without a recent or past history of asthma symptoms, negative history of treatment with asthma-specific medication (short action beta-2-agonists, inhaled or systemic steroids, leukotriene receptor antagonists, and theophylline), present or past tobacco smoking, or any other condition that could disable FENO measurement. Schoolchildren were interviewed by a paediatric respiratory physician at school and with the help of class teachers, to identify healthy children. Parents of those students selected as healthy were asked to answer a simple questionnaire on the use of asthma medications and past/current symptoms of asthma, rhinoconjunctivitis and eczema (based on the ISAAC questionnaire)7; atopy was considered as possible when parents answered positively to any of the questions on rhinoconjunctivitis, or eczema.8,9

On-line single breath FENO measurements were performed at schools, during the morning with a portable device (NIOX MINO, Aerocrine AB, Solna, Sweden) using an electrochemical sensor, by the study physicians, and according to ATS guidelines.1

After a brief demonstration about the procedure, children were asked to inhale to total lung capacity through the mouthpiece connected to the FENO device and then exhale slowly for 10s at 50ml/s, assisted by audiovisual cues provided by the device.

This study had the approval of the Scientific Ethics Committee, Chilean Ministry of Health, Southern Metropolitan Area of Santiago de Chile and written informed consent was given by parents. The study was performed with the permission and collaboration of school authorities and teachers.

Data analysesThe distribution of FENO measurements was right-skewed, then analyses were performed with log-transformed data, as well as for other variables without normal distribution, but results are shown as back-transformed values. Values of FENO are presented as geometric mean (GM) and upper limit of the 95% reference interval. Factors that may affect FENO (age, sex, weight, height, passive tobacco exposure), as well as reported symptoms of rhinitis or eczema, were analysed using multiple regression. Comparisons of mean FENO values by gender (boys, girls), age (between children aged <12 years and ≥12 years), passive tobacco exposure (yes/no) and atopy by questionnaire (yes/no) were performed by ANOVA and a p value<0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

ResultsOne hundred and ninety children (85 boys) completed the study. The group had a mean age of 11 years (95%CI 10.8–11.2), height 147.8cm (95%CI 146.2–149.4) and weight of 45.9k (95%CI 44.0–48.0). The mean FENO was 15.4ppb (95%CI 14.7–16.2) and the upper limit of the 95% reference interval, right-sided, was 27.4ppb (90%CI 25.6–29.2). The lowest and highest FENO values were 6ppb and 35ppb, whereas the 5th and 95th percentiles were 9.0ppb (95%CI 8.0–10.0) and 28.0ppb (95%CI 26.7–30.4), respectively.

There was a significant positive association between FENO and height (p=0.031), (Fig. 1a), but not with age (p=0.55; Fig. 1b) or weight (p=0.12; Fig. 1c). There was no significant difference in FENO between children aged <12 years (15.6ppb, 95%CI 14.6–16.7) and those aged ≥12 years (15.1ppb, 95%CI 13.9–16.4), p=0.14, neither between boys (16.0ppb, 95%CI 14.7–17.3) and girls (16.7ppb, 95%CI 15.5–17.8), p=0.87. No significant difference was found when comparing FENO between children with and without positive parent-reported rhinoconjunctivitis (yes=14.5ppb, 95%CI 12.9–16.3 and no=16.1ppb, 95%CI 15.0–17.3; p=0.12), or eczema (yes=15.1ppb, 95%CI 13.0–17.7 and no=15.9ppb, 95%CI 14.9–17.0; p=0.57). Passive tobacco smoke exposure was present in 50.8% of them but the difference in FENO between those exposed (16.5ppb, 95%CI 15.1–18.0) and not exposed (15.1ppb 95%CI 13.9–16.4) was not significant (p=0.16).

DiscussionThis study shows that FENO levels in healthy non-smoking Chilean children aged 8–15 years, measured following ATS recommendations,1 ranged from 9.0ppb (5th percentile) to 28.0ppb (95th percentile), with a geometric mean of 15.4ppb and upper limit of the 95% reference interval of 27ppb (rounding down from 27.4ppb). To the best of our knowledge this would be the first information on reference values of FENO for Latin American children measured by a portable device using an electrochemical sensor.

Several factors would influence FENO measurements in healthy children i.e., age, gender, height, ethnicity, self-reported atopy, allergic sensitisation, total IgE, time of testing, infections, a nitrate-rich diet, exercise, smoking, ambient nitric oxide, time of the day and season, environmental pollution, among others.1–5,10–15 However, the significant effects of age, gender, height, weight, ethnicity, and other factors, on FENO values in healthy children are not consistent, even in children from similar populations or ethnic background14,16–20; the latter coincides with the large variation of FENO reference values among studies. Although this could be partially explained by the wide variability of normal FENO values in general population,21 it may also be the result of the marked differences among studies regarding methodology to select healthy children, devices used for measuring FENO, and ways of reporting measurement results i.e., mean, geometric mean, median, percentile range, and upper limits, among others.

Indications for the clinical interpretation of FENO levels have been provided by the American Thoracic Society (ATS) in their FENO guideline1 stating that eosinophilic airway inflammation, and responsiveness to corticosteroids are less likely with FENO levels <25ppb in children ≥12 years of age and <20ppb in those younger than 12 years old. Values of FENO greater than 35ppb in children indicate that eosinophilic inflammation and, in symptomatic patients, responsiveness to corticosteroids are likely. However, it is not clear yet if these cut-off values are applicable to healthy children from different populations and environments, particularly when measuring FENO with portable devices.

Our 95% reference interval upper limit of 27ppb, even when lower than recommended by ATS, could be used as the upper threshold of FENO measured by NIOX MINO device when assessing asthmatic children from a population similar to this study. As no significant relationship was found between FENO and gender or age, it is likely that when assessing asthma in schoolchildren, FENO values over 27ppb could indicate the likelihood of eosinophilic airway inflammation in girls and boys in the age range of this study.

We did not find (PubMed) published information on FENO reference values or cut-offs for Latin-American healthy children, measured using an electrochemical sensor as used in the present study. There is little data on reference values for Spanish healthy children and Pérez et al.,22 using NIOX MINO, reported a FENO cut-off of 19 ppb; in a US general population study (NHANES), using the same device for FENO measurements, the 97.5th percentiles for Hispanic children aged 4–11 and 12–19 years were 36ppb and 71ppb, respectively10 while FENO geometric mean for those age groups was 8.6ppb and 12.1ppb, respectively.

Differences in FENO reference values have also been found for Arab and Chinese healthy children. In Qatari children, Jahani et al.20 measuring FENO by NIOX MINO reported a geometric mean of 14.1ppb with a 95% confidence interval for the upper FENO level of 36.3ppb. In North African, Tunisian healthy children, Rouatbi et al.19 found that a mean±SD of FENO was 5.0±2.9ppb ranging from 1.0 to 17.0 (measured with another type of portable FENO device). In mainland China, Zhao et al.,23 measuring FENO with NIOX MINO in non-wheezing adolescents from two cities, reported a geometric mean of 13.8±1.7ppb, while Yao et al.16 using another device in Taiwanese children found a geometric mean FENO of 13.7ppb, whereas in Hong Kong13 Wong et al. found a median FENO of 17ppb in boys and 10.8ppb in girls. A study including US and European healthy children aged 4–17 years8 found a FENO geometric mean of 9.7ppb and upper 95% confidence limit of 25.2ppb, with significant differences in FENO levels between countries and localities, and also regarding ethnic background.

Using data from NAHNES (US general population)21 it has been found that 5th and 95th percentile of FENO values in children aged less than 12 years without reported asthma or wheeze in the last 12 months were 3.5ppb and 36.5ppb, respectively. For subjects 12–80 years of age the 5th and 95th percentile FENO values were 3.5ppb and 39ppb. Thus, in that population values exceeding the 95th percentiles would indicate a high risk of airway inflammation. In the same study it was found that children 6–11 years old without self-reported asthma or wheeze in the previous 12 months had a predicted FENO of 9.0ppb, very similar to those with self-reported asthma but no attacks or wheeze in the previous 12 months (9.2ppb) and this might allow an extrapolation to clinic work in the general sense that in children with well-controlled asthma, FENO values would tend to be similar to those in children without current history of asthma, although an overlapping of FENO values in normal and asthmatics is also likely.

Since we did not measure atopy by skin prick test or other plasmatic markers of atopy we were not able to objectively determine the presence of asymptomatic atopic healthy children in our study group. Although we used a validated questionnaire to detect children with past or current symptoms of rhinoconjunctivitis or eczema, we acknowledge the limitations for confidently diagnosing atopy using parent-reported symptoms in children. On the other hand, commonly used biomarkers for atopy, such as serum IgE and skin prick tests, are poorly correlated24 between them or with clinical disease. The possibility of collecting a healthy group of children for determining “normal” FENO values or cut-off points could be limited by several situations such as measuring during viral or pollens season, periods of increased air pollution (smog), among others, which would influence the level of FENO.1–5 We did FENO measurements during April, a month where common viral respiratory infections, pollen levels and smog are low in our locality, and what added to the short period of data collection (four weeks) would help to decrease the potential variability introduced by changing exposures during longer data collection time. In addition, the rigorous method we used to identify healthy children by using both a medical interview and a parent questionnaire strengthen our results. During the interview, the paediatric respiratory physician showed asthma medications (metered-dose inhalers and spacers) to children to determine if they had used some inhaled medications recently or in the past. We also looked for the absence of upper or lower respiratory tract disease in the recent past at the moment of FENO measurements, and thoroughly try to avoid confounding factors that may affect FENO measurements according to ATS recommendations.1 Thus, we consider that a strength of this study is to have collected a group of healthy non-smoker schoolchildren, without recent or past history of asthma symptoms, negative history of treatment with asthma-specific medication, no evident acute respiratory infection (cold, flu) within the last 10 days, or any other condition that could disable FENO measurement. All the above information was collected by specialists in paediatric respiratory diseases who also performed the FENO measurements.

Our result of a geometric mean FENO (back-transformed) of 15.4ppb and 95% reference interval upper limit of 27ppb, and 5th (9.0ppb) and 95th (28.0ppb) percentiles are well within values reported by other authors in otherwise healthy children. However, the wide variation in references values, percentile ranges, upper limits and cut-offs values reported for FENO in healthy children from different localities suggests that data obtained for one population are not suitable for direct extrapolation to children from another ethnic background or environmental conditions. Until multicentre international studies using standardised methodology for measuring FENO in healthy children are available, it appears recommendable that laboratories or centres generate their own FENO reference and threshold values.

ConclusionsWe have established reference values of FENO for healthy Chilean children lifetime-free from asthma symptoms and non-smokers. This study suggests that FENO values higher than 27ppb are likely abnormal and would reflect airway inflammation in children 8–15 years old.

Author contributionsAll authors participated in conception and design; data collection, analysis, and interpretation; drafting and revising manuscript; and approval of final manuscript.

FundingThe study was supported by the Post Graduate Office, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Santiago de Chile (USACH), and Hospital CRS El Pino, Santiago, Chile.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human subjects and animals in researchThe authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the responsible Clinical Research Ethics Committee and in accordance with those of the World Medical Association and the Helsinki Declaration.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.