Filaggrin (FLG), which is formed from profilaggrin protein during epidermal terminal differentiation, is a prerequisite to squame biogenesis and thus for perfect formation of the skin barrier. Yet, the relationship between genetic polymorphisms of FLG and chronic idiopathic urticaria (CIU) has not been investigated.

MethodsThe study population consisted of 93 CIU patients and 93 healthy control subjects without a history of allergic, autoimmune or any other systemic disease. Five single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of FLG were investigated: rs2485518, rs3126065, rs2786680, rs3814300, and rs3814299.

ResultsFor all the investigated polymorphisms, 100% of both CIU patients and control subjects exhibited one given allele and consequently one given genotype as following: A/A genotype for two SNPs, rs3126065 and rs2786680, C/C genotype for two SNPs, rs2485518 and rs3814300, and G/G genotype for one SNP rs3814299 of FLG, and hence no association was found between either allele frequencies or genotype distributions of FLG SNPs and CIU in an Iranian population.

ConclusionsThe present study examined the possible relationship between SNPs of FLG and CIU for the first time, and demonstrated that none of five investigated SNPs (rs2485518, rs3126065, rs2786680, rs3814300, and rs3814299) are correlated with CIU in an Iranian population. Further investigations are required to address whether ethnicity/race impacts on relationship between SNPs of FLG and CIU.

Chronic urticaria (CU) is characterised by widespread smooth, oedematous wheals occurring daily or almost daily for more than six weeks.10 Angio-oedema seems a common occurrence in CU, due to its observation in more than one third of patients.17 In approximately 20% of CU adults, the disease duration is longer than one year, and women are more likely to develop CU than men.8 It is not altogether surprising that the heavy burden of CU falls on many aspects of daily life, including mobility, sleep and social interactions.26 CU is categorised under three main headings, physical urticaria, urticarial vasculitis and chronic idiopathic urticaria (CIU). Detection of histamine-releasing IgG autoantibodies against either the high-affinity IgE receptor Fc¿R1 or IgE in sera of CIU patients has led to label 25–50% of CIU patients as autoimmune urticaria and thereby to manage more effectively the disease in these patients by means of problem solving-based strategies such as plasmapheresis.9,11,14,25 Additionally, complement system, cytokines, chemokines and adhesion molecules are of pathogenic findings in CU, which collectively cause in recruiting a wide range of immune cells, e.g. CD4+ lymphocytes, neutrophils, basophils and monocytes.17 In addition to the immunological basis of CIU, several studies have suggested that the generation of oxidative stress damage, as assessed by levels of reactive oxygen species and activity of superoxide dismutase, may be a key stimulus to the pathogenesis of CIU.5 More interestingly, it attracts a great deal of attention that most CIU patients have determined stress as the exact cause of their disease.29

Nevertheless, despite nearly a century of research, the chief factor(s) of CU remain unknown; there is, thus, a conspicuous absence of efficient treatments for a considerable number of cases, who are still considered idiopathic. Findings of substantially increased risk of CIU in people with at least one positive first-degree history of CIU than in general population,1 in addition to the proven genetic associations provided by population-based genetic association studies,27,37 do really appreciate the value of genetic investigations to unveil the nature of CIU.

The protein filaggrin (FLG) acts as an intermediate filament-associated protein and aggregates keratin intermediate filaments in mammalian epidermis; FLG is, thus, required to complete correctly keratinocyte construction and to properly maintain the permeability of the epidermal barrier.12 The gene encoding FLG located on chromosome 1q21.3 is the most associated gene with atopic dermatitis (AD) (for review see Ref. [2]). Regarding CIU, a recent finding has indicated significant upregulation of the FLG expression in lesional CIU patients more than in AD patients, and as well significant increased staining intensity of FLG in lesional CIU patients compared with either AD patients or control subjects.41 Furthermore, the research demonstrated a significant association between filaggrin staining intensity and urticaria activity score.41 However, the relationship between genetic polymorphisms of FLG and CIU has yet to be investigated. We accomplished the present case-control study to address the question as to whether single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of FLG are associated with susceptibility to CIU.

Materials and methodsSubjectsBlood samples were obtained from 93 Iranian CIU patients who were referred to the Children's Medical Centre, the Paediatrics Centre of Excellence in Tehran, Iran. The group of control subjects was set up from healthy members without a history of allergic, autoimmune or any other systemic disease. All CIU cases were diagnosed according to the standard international criteria,20 i.e. the wheals lasting for six weeks or longer with occurrences of at least two times a week and its underlying cause remained unclear despite the appropriate investigations. Patients with physical urticaria, food/medication induced allergy or urticarial vasculitis were excluded. Other exclusion criteria were urticaria lesions due to infections, environmental agents, stress or cholinergic stimulation and heat/cold induced urticaria, dermatographic urticaria and pressure induced urticaria. To correctly exclude the aforementioned aetiologies, the onset and duration of lesions, characteristics of lesions, distribution of lesions, and history of any associated disease or allergies, drug history and complement deficiencies were considered. Specific laboratory tests were performed to approve the suspicious diagnosis, for instance C3, C4, CH50 and C1 inhibitor (C1-INH) for angio-oedema. DNA was extracted from nucleated cells according to the phenol–chloroform protocol.7

All individuals enrolled in the study gave their written consent. This study was approved by the ethics committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences (TUMS).

GenotypingIn the present study, FLG polymorphisms were identified by means of polymerase chain reaction with the sequence specific primers (PCR-SSP) assay (PCR-SSP kit, Heidelberg University, Heidelberg, Germany). A PCR Techne Flexigene apparatus (Rosche, Cambridge, UK) was applied for the amplification of extracted DNA. PCR products were observed by 2% agarose gelelectrophoresis and a picture was taken after visualisation with a UV transilluminator. Five SNPs of FLG were investigated: rs2485518, rs3126065, rs2786680, rs3814300, and rs3814299. Laboratory personnel were blinded to the study.

Statistical analysisFor each one of the five investigated SNPs, genotype distributions and allele frequencies were calculated by direct gene counting. Pearson's chi-squared test was used in examining the differences in the distribution between CIU cases and healthy controls. All the statistical analyses of the present study were implemented using the Epi Info statistical software (version 6.2, World Health Organisation, Geneva, Switzerland).

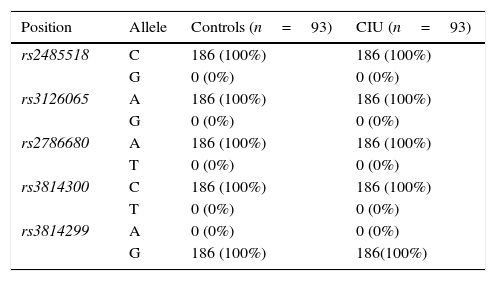

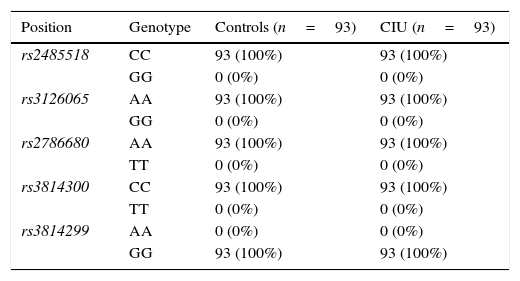

ResultsAllele and genotype frequenciesThe allele frequencies and genotype distributions of FLG polymorphisms for CIU cases and control subjects are summarised in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. For all the investigated polymorphisms, 100% of both CIU patients and controls exhibited one given allele and consequently one given genotype as following: A/A genotype for two SNPs, rs3126065 and rs2786680, C/C genotype for two SNPs, rs2485518 and rs3814300, and G/G genotype for one SNP rs3814299 of FLG. For this reason, either allele frequencies or genotype distributions of FLG SNPs were not associated with CIU in this Iranian population and ORs could not be defined to estimate the relative risk.

Allele frequencies of filaggrin polymorphisms in patients with chronic idiopathic urticaria and controls.

| Position | Allele | Controls (n=93) | CIU (n=93) |

|---|---|---|---|

| rs2485518 | C | 186 (100%) | 186 (100%) |

| G | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| rs3126065 | A | 186 (100%) | 186 (100%) |

| G | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| rs2786680 | A | 186 (100%) | 186 (100%) |

| T | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| rs3814300 | C | 186 (100%) | 186 (100%) |

| T | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| rs3814299 | A | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| G | 186 (100%) | 186(100%) |

n, number of participants in each group.

Genotype distribution of filaggrin polymorphisms in patients with chronic idiopathic urticaria and controls.

| Position | Genotype | Controls (n=93) | CIU (n=93) |

|---|---|---|---|

| rs2485518 | CC | 93 (100%) | 93 (100%) |

| GG | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| rs3126065 | AA | 93 (100%) | 93 (100%) |

| GG | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| rs2786680 | AA | 93 (100%) | 93 (100%) |

| TT | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| rs3814300 | CC | 93 (100%) | 93 (100%) |

| TT | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| rs3814299 | AA | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| GG | 93 (100%) | 93 (100%) |

n, number of participants in each group.

Filaggrin, which is formed from profilaggrin protein during epidermal terminal differentiation, is a prerequisite to squame biogenesis and thus for perfect formation of the skin barrier.33 Therefore, when filaggrin or its prerequisite, profilaggrin, are in abnormal supply, either plentiful or limited, the skin cannot function as an effective barrier against environmental factors, such as UVB,24 and thereby a spectrum of clinical and immunopathological manifestations particularly related to atopic and allergic diseases and infections are produced. For example, skin biopsies taken from either AD patients or patients with ichthyosis vulgaris provided evidence of a significant downregulation in the filaggrin expression compared with controls, whereas its considerable upregulation in lesional CIU skin.15,36,42 Evaluating the interaction between filaggrin and the immune system must be addressed as a matter of urgency to unfold subsequent pathological events of the dysregulated, either up- or down-regulated, expression of filaggrin.

Conducting research into AD keratinocytes concluded that inverse correlations exist between the expression level of filaggrin and cytokines, which are involved in chronic inflammatory processes (IL-4 and IL-13).15 However, such correlations do not imply causation. Experimental studies using filaggrin knockdown protocol and case-control studies on carriers of filaggrin null mutations directly reflect the impact of filaggrin on the immune system. For instance, in human keratinocyte cells, filaggrin knockout caused in the increased thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP), IL-6 secretion and toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3) stimulation in response to poly(I:C).21 As well, percutaneous immune responses, measured by hapten-induced contact hypersensitivity and serum levels of anti-ovalbumin IgG1 and IgE, were appeared significantly more prominent in the FLG−/− stratum corneum than wild-type controls.18,28 Chronologically, in the long-term, the filaggrin deficiency led to the increased infiltration of CD4+ cells and expression of IL-6, IL-17 and IL-23 at age eight weeks, when the skin was still apparently normal, and to the increased expression of IL-4 at age 32 weeks, when eczematous skin lesions were generated.28 Consistent with findings of experimental studies, AD patients, who were carriers of filaggrin mutations, had significantly increased levels of IL-1 cytokine in stratum corneum (SC) than patients without these mutations.19 On the other side, it has been elucidated that some cytokines, such as IL-22, downregulate the expression of both filaggrin and profilaggrin in keratinocytes.13 Altogether, these lines express the support for the notion that the immune system will be swayed by or holds sway over expression of filaggrin, i.e. there is an interaction between filaggrin and the immune system.

The downregulated expression of filaggrin can be partially attributed to loss of function genetic variants such as R510X and 2282del4, which are characterised by a semi-dominant phenotype affecting approximately 9% of the European population and making a dramatic reduction in the protein levels of filaggrin.16,30,35 Filaggrin null mutations affect half or more of European children with moderate to severe AD.30 In contrast, both studies accomplished on an African population have declared that African AD patients completely lack four prevalent null mutations, including R501X and 2282del4, of filaggrin associated with AD in European and Asian people, and as well the filaggrin expression in their skin was not altered compared with controls, highlighting the importance of ethnicity on filaggrin-related genetic background.38,40 However, African AD patients had significantly lower concentrations of two products of FLG degradation, urocanic acid and pyrrolidone-5-carboxylic acid, in SC than controls, evidencing a genetic-independent mechanism for down-regulated function of filaggrin in AD in Africans.38 This decreased amount of breakdown products of filaggrin was found to correlate positively with total copy number variation (CNV) within the filaggrin gene in the Irish AD paediatric population.4 In addition to those prevalent mutations, which have been frequently and strongly associated with AD, ichthyosis vulgaris, eczema and concomitant asthma, some relatively rare genetic mutations have been discovered in people with either Caucasian or Asian race, explaining that filaggrin-related genetic background of AD is not solely confined to prevalent mutations and founding novel, but rare, genetic mutations are of interest research areas in this regard.3,6,23,32,34,39 To exemplify, more than 40% of Irish AD patients carry at least one filaggrin null mutation, with all the mutations except one-fifth of them are comprised by p.R501X and c.2282del4, and as well in Polish AD patients, the combined allele frequency of these prevalent mutations is estimated ∼20%, whereas wide-spectrum study of the filaggrin gene indicates that filaggrin null mutations occur only in 20% of Chinese AD patients, which included 17 different mutations.6,22

Despite its limitations, to our knowledge, the present study examined the possible relationship between SNPs of FLG and susceptibility to CIU, as a disease associated with increased expression of filaggrin, for the first time, and demonstrated that none of five investigated SNPs (rs2485518, rs3126065, rs2786680, rs3814300, and rs3814299) are correlated with susceptibility to CIU. Similarly, we have not found any associations between those mentioned SNPs and AD in an Iranian population (unpublished data). In both studies, 100% of all CIU and AD cases and control subjects carried one common haplotype of investigated genetic variants of FLG. Presumably, these genetic variants of FLG are, thus, not polymorphic or very rare in Iranian people however, future studies with larger sample sizes are necessary. Accordingly, the result of the present study, i.e. lack of any correlation between SNPs of FLG and CIU, should be interpreted with excessive caution, due to the fact that ethnically diverse populations represent genetically diverse patterns, which both cause in calculating complex relationships between genetic variants and risk of susceptibility to common diseases. For example, a meta-analysis study evaluating the association between the IL-1β-511 variant and febrile seizures (FSs) has recently indicated significantly more development of FSs in Asian, but not in Caucasian, people, who were carriers of TT genotype.31 Moreover, among more than forty genes associated with AD, FLG has been chosen as the best candidate gene supporting this fact, as described above.2 Further investigations in other ethnicities are required to establish an ethnicity-dependent distribution pattern for SNPs of FLG in CIU; as found for AD.2 The neglect of measurement of the filaggrin expression is the most important limitation of the present study, which must be attended to conduct future researches.

Ethical disclosuresConfidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data and that all the patients included in the study have received sufficient information and have given their informed consent in writing to participate in that study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects mentioned in the study.

Protection of human subjects and animals in researchThe authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the responsible Clinical Research Ethics Committee and in accordance with those of the World Medical Association and the Helsinki Declaration.

FundingThis study was supported by a grant from Tehran University of Medical Sciences (grant no. 91-02-93-18392).

Conflict of interestAuthors declare no conflicts of interest.