The disease spectrum that can be triggered by the Epstein–Barr Virus (EBV) is very wide, from infectious mononucleosis1 to more serious entities such as chronic active EBV infection, haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH), the X-linked lymphoproliferative disease and other lymphoproliferative disorders such as T, B and NK lymphomas.1 With the exception of infectious mononucleosis, these other medical conditions should always arise suspicion of an underlying defect of immunity.

HLH is a clinical syndrome that occurs due to an exaggerated inflammatory reaction as a result of an inadequate response of the immune system.2 The term haemophagocytosis describes the pathognomonic findings of activated macrophages surrounding erythrocytes, leukocytes, platelets and their precursors. Clinically, HLH is characterised by prolonged fever, pancytopenia, hepatosplenomegaly, and haemophagocytosis in bone marrow, liver, lymph nodes and central nervous system.2 These events constitute the clinical and laboratory criteria used for HLH diagnosis.2 HLH was initially thought to be a sporadic syndrome caused by a neoplastic proliferation of histiocytes.3 Subsequently, familial cases were described, which are currently known as Familial Haemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis (FHL). The relationship of HLH with viral infections, and other microorganisms has been demonstrated over time.1,2,4 Currently the incidence of HLH worldwide is 1.2 cases per million persons per year.2,5 HLH is divided into two forms: primary or familial, and secondary or acquired. The primary form includes the FHL, in which HLH is the only clinical manifestation of the genetic defect. FHL presents in children under one year of age in 70% of the cases, and has an incidence of 1/1 million newborns per year.2 The primary form also includes a syndromic form in which the manifestations of haemophagocytosis are associated with other clinical features such as partial albinism (Chédiak-Higashi and Griscelli syndromes) and lymphoproliferation (X-linked lymphoproliferative disease).2 The acquired form of HLH can occur at all ages. It was initially described in the context of viral infections but has now been linked to many other infections such as fungi, bacteria and parasites (leishmaniasis in particular).2,6 Also, HLH can occur in the context of autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus, juvenile idiopathic arthritis or Kawasaki disease.2 In fact, any intense stimulation of cellular immunity (infection, rheumatism, tumour) could virtually trigger a secondary form of HLH.

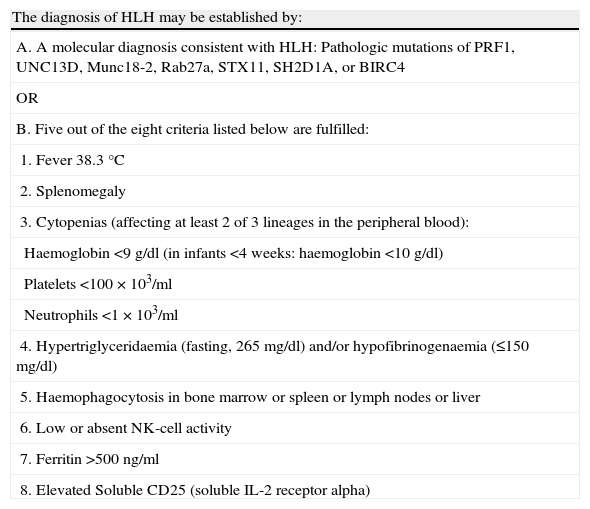

A girl aged 24 months complained of fever lasting for 20 days, associated with suppurative sore throat, generalised lymphadenopathy and hepatosplenomegaly. She was diagnosed of infectious mononucleosis, with a viral load for EBV of 6350copies/ml. There was no relevant personal or family history. Due to persistent fever and malaise, she was admitted to hospital. Blood tests revealed panhypogammaglobulinaemia at the expense of IgG (3305mg/l, normal value (NV): 4350–11,200mg/l), associated with low IgA and IgM, along with B cell lymphopenia and an expansion of CD8+ lymphocytes. Intravenous acyclovir and immunoglobulin replacement therapy were started. In the following days, the patient remained febrile and had a progressive clinical and analytic worsening: she developed bicytopenia with severe thrombocytopenia (54,000/ml) and anaemia (hb: 8.4g/dl), increasing hepatosplenomegaly and rise of EBV viral load, maximum values of 340,568copies/ml. Then, the possibility of a haemophagocytic syndrome was suspected, for which the study was extended to include: ferritin (1517ng/ml, VN: 10–120ng/ml), LDH (1194UI/l, VN: <776IU/l), triglycerides (901mg/dl, VN: 50–185mg/dl) and bone marrow aspirate, which was negative for haemofagocytes. The cytotoxic activity of NK cells was also evaluated, and was absent. Thus the patient met the diagnostic criteria for HLH (Table 1) and the therapeutic protocol for this condition (HLH-2004 protocol)7 was started. This protocol included a combination of daily intravenous dexamethasone (10mg/m2), twice weekly intravenous etoposide (VP-16, 150mg/m2), which were both weekly tapered if good response was obtained, and oral daily cyclosporine A (6mg/kg), plus prophylactic monthly intravenous immunoglobulins and cotrimoxazole three times weekly. Antiviral treatment was also switched to Ganciclovir (10mg/kg/day)±Foscarnet (90mg/kg/day). The patient had a good initial response to treatment, achieving a partial remission of the inflammatory state. After eight weeks of treatment, she had a relapse of the HLH. NK cytotoxic function was repeated, and still absent, which was indicative of primary haemophagocytic syndrome or FHL. The treatment protocol was restarted and a donor search was initiated for bone marrow transplantation. During the wait, the control of EBV infection was very difficult: on top of antivirals, treatment with monoclonal anti-CD20 was added: CD20 is a surface marker of mature B cells, which act as the reservoir of EBV. The aim of such treatment was to reduce the EBV viral load4,8. Finally, genetic tests confirmed a final diagnosis of FHL type 3. Six months after onset, the patient received bone marrow transplantation from a matched-unrelated donor, which allowed curing her primary immunodeficiency.

Diagnostic criteria for HLH, established for the conduct of the HLH-2004 trial.

| The diagnosis of HLH may be established by: |

| A. A molecular diagnosis consistent with HLH: Pathologic mutations of PRF1, UNC13D, Munc18-2, Rab27a, STX11, SH2D1A, or BIRC4 |

| OR |

| B. Five out of the eight criteria listed below are fulfilled: |

| 1. Fever 38.3°C |

| 2. Splenomegaly |

| 3. Cytopenias (affecting at least 2 of 3 lineages in the peripheral blood): |

| Haemoglobin <9g/dl (in infants <4 weeks: haemoglobin <10g/dl) |

| Platelets <100×103/ml |

| Neutrophils <1×103/ml |

| 4. Hypertriglyceridaemia (fasting, 265mg/dl) and/or hypofibrinogenaemia (≤150mg/dl) |

| 5. Haemophagocytosis in bone marrow or spleen or lymph nodes or liver |

| 6. Low or absent NK-cell activity |

| 7. Ferritin >500ng/ml |

| 8. Elevated Soluble CD25 (soluble IL-2 receptor alpha) |

One of the biggest challenges of the haemophagocytic syndrome is the diagnosis. The signs and symptoms are compatible with other common diseases such as infections, tumours and rheumatic diseases.5 Specifically, HLH should be included in the differential diagnosis of other clinical conditions such as: (1) fever of unknown origin; (2) hepatitis with coagulopathy (30% of the HLH patients present a rise in transaminases above 100U/l)5; (3) sepsis with multiple organ failure; and (4) lymphocytic encephalitis: the HLH can present with neurological symptoms due to CNS infiltration by activated macrophages. Also, severe or unusual progression of symptoms in a common disease should raise the doubt of an HLH complicating the underlying condition. For instance, in our 20-month-old patient, it was the EBV infection that remained severely symptomatic for more than 15 days with progressive deterioration of general condition, which motivated the suspicion of HLH. Indeed, infectious mononucleosis by EBV is usually benign, poorly symptomatic and self-limited to a maximum 10 days in toddlers.1 In 1979, Risdall et al. published the association of EBV with haemophagocytic syndrome, and named the entity the virus-associated haemophagocytic syndrome. Since then, it has been noted that EBV is a common trigger of haemophagocytosis, in both primary and secondary HLH.1,5

Progress has been made in clarifying the pathophysiology of HLH.2,3,6 Sequentially, first there is a defect in the cytotoxic function of CD8+ lymphocytes and NK cells, either primary (genetic defect) or secondary (to infection or treatment). This defect hinders both the control of lymphocytes that are proliferating in response to infection and the removal of infectious agents that have intracellular cycle. Then, the sustained and uncontrolled activation of the immune system, with consequent elevation of inflammatory cytokines, is responsible for the clinical manifestations of HLH. Genetic defects have been identified in the forms of FHL: defect in PFR1 (13–50%), in UNC13D (17–30%), in STX11 (<10%) and in STXBP2 (10%).2 In the forms of HLH secondary to infection, the pathophysiology is unclear, but it is considered that the virus can interfere with the function of CD8+ T cells through specific proteins and thereby produce high levels of cytokines.2,4 The laboratory findings of HLH include: cytopenia, of at least two cell lines, hypertriglyceridaemia, hypofibrinogenaemia, coagulopathy and hyperferritinaemia. Sometimes FHL can present with hypogammaglobulinaemia. Ferritin values greater than 500ng/ml have a sensitivity of 84% for HLH, and above 10,000ng/ml, 90% sensitivity and 96% specificity.2,9 Bone marrow aspirate reveals usually normal cell maturation with hypercellularity. The presence of bone marrow haemofagocytes at onset of HLH is only seen in 30–40% of cases, increasing the difficulty of the diagnosis; this percentage increases to 80–90% with the progression of the disease.2,4 The cytotoxic function of NK cells should always be assessed for the diagnosis of HLH, and should be decreased or absent, both in primary and secondary forms. The difference is that in primary forms, the defect persists over time even without the clinical symptoms of HLH. Along with cytotoxic function, other specific tests can be performed to complete the study of primary HLH, such as measurement of perforin expression and degranulation tests.2,4

Both primary and secondary HLH can be rapidly fatal and require early treatment.10 Treatment can be performed stepwise depending on the severity of HLH and the suspicion of a primary versus a secondary form: the main treatment is dexamethasone (5–10mg/m2) because of its cytotoxic effect on lymphocytes, the inhibition of cytokine production and dendritic cell differentiation. It is combined with cyclosporin A (6mg/kg/day), which interferes in the activation of lymphocytes and macrophage function. Etoposide (150mg/m2 one or twice weekly) can be used in secondary HLH triggered by EBV, and in primary HLH, since it kills antigen presenting cells, including macrophages7,8,10. Along with this immunomodulary treatment, the trigger of the HLH should always be treated, such as infection, tumour or rheumatic disease. The combination of these drugs in HLH-2004 protocol has shown a survival of 64% at three years. Finally, in primary forms, an evaluation for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation should be started as soon as the diagnosis is made.2,7

To sum up, the haemophagocytic syndrome is a rare entity with high morbidity and mortality, which should always be included in the differential of atypical and severe febrile syndromes. This will enable early diagnosis and the establishment of a specific treatment for improved survival. Similarly, in a persistent EBV infection, underlying primary immunodeficiencies should be ruled out, because they can have an impact on the patient's prognosis.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that we have followed the protocols of our hospital on the publication of patient data and that the patient included in the study has received sufficient information and has given their informed consent in writing to participate in the study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the informed consent of the patient mentioned in the article.